Unveiling the Algorithm: The Role of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Modern Surgery

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Rise of AI in Surgery

1.2. Why Explainability Matters in Surgical AI

1.3. Aim of the Review

2. Methods

3. Foundations of Explainable AI in Surgical Contexts

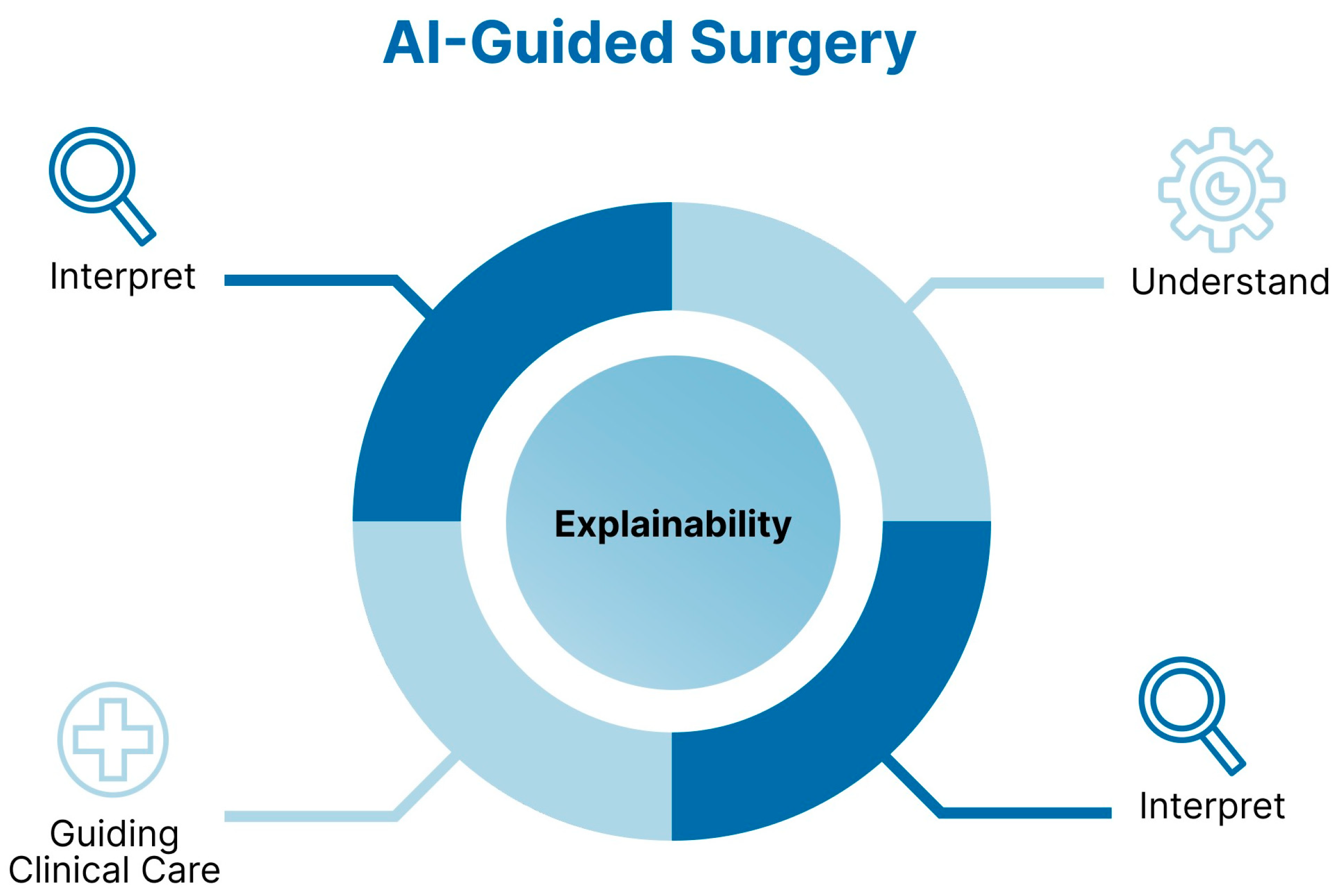

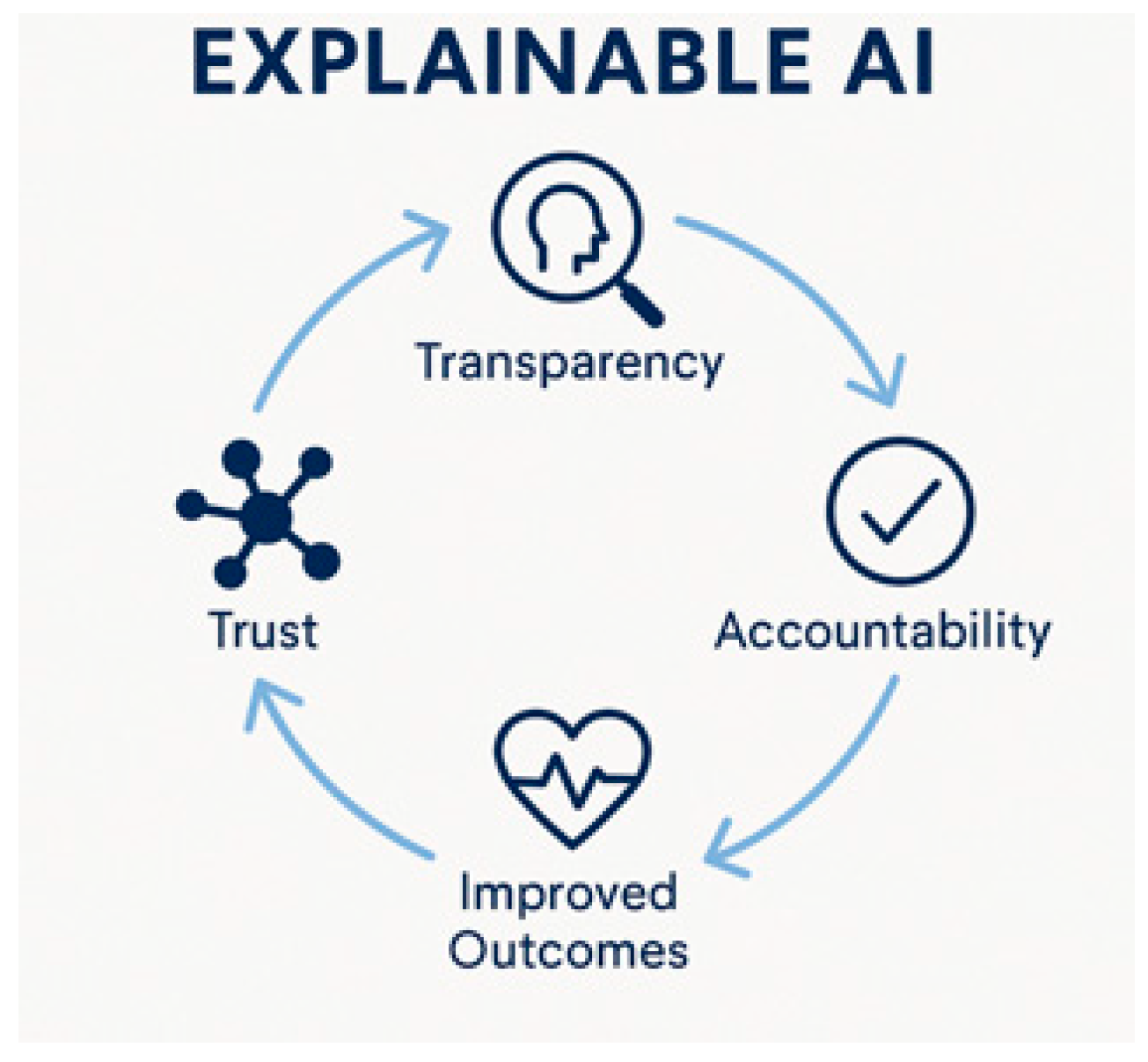

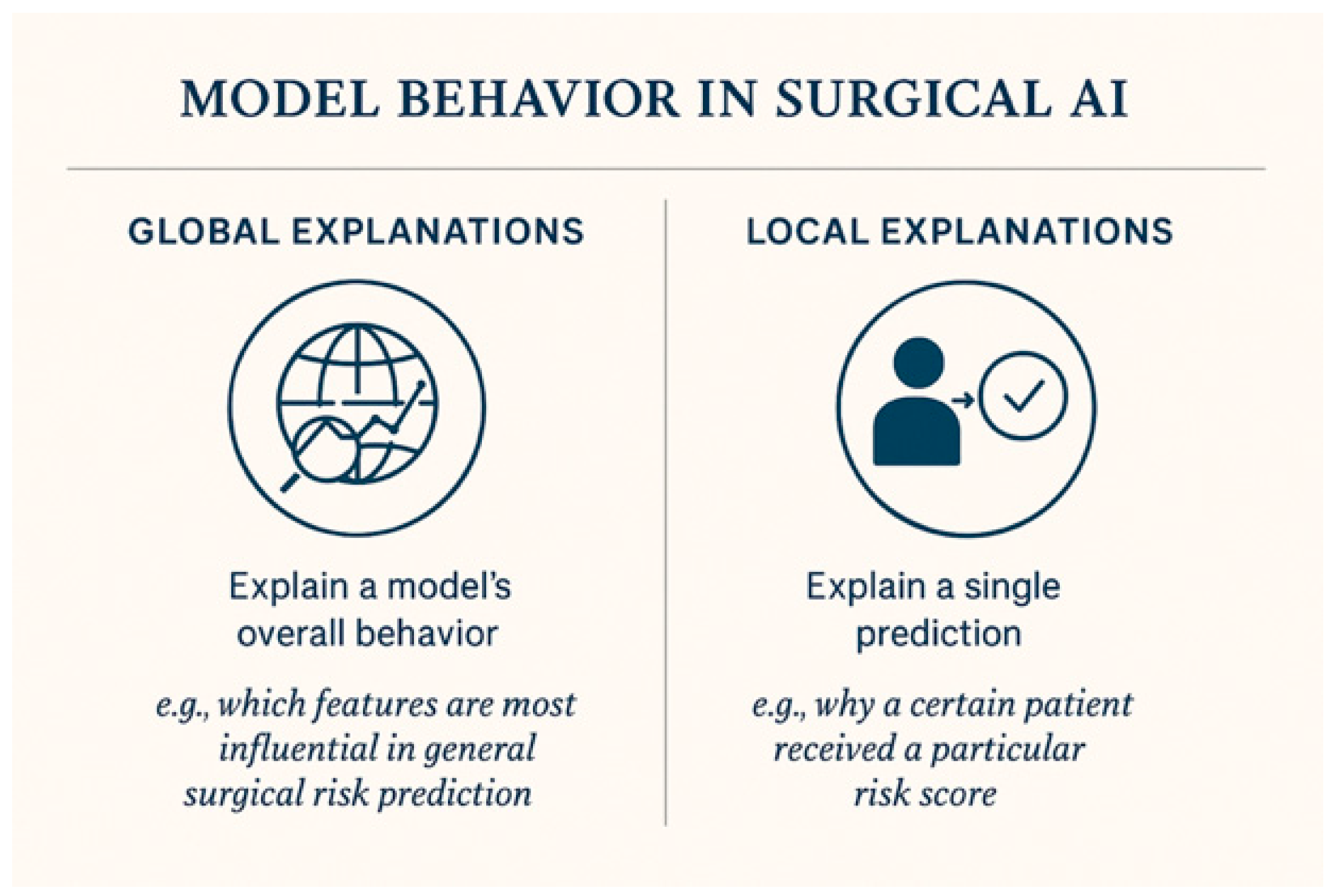

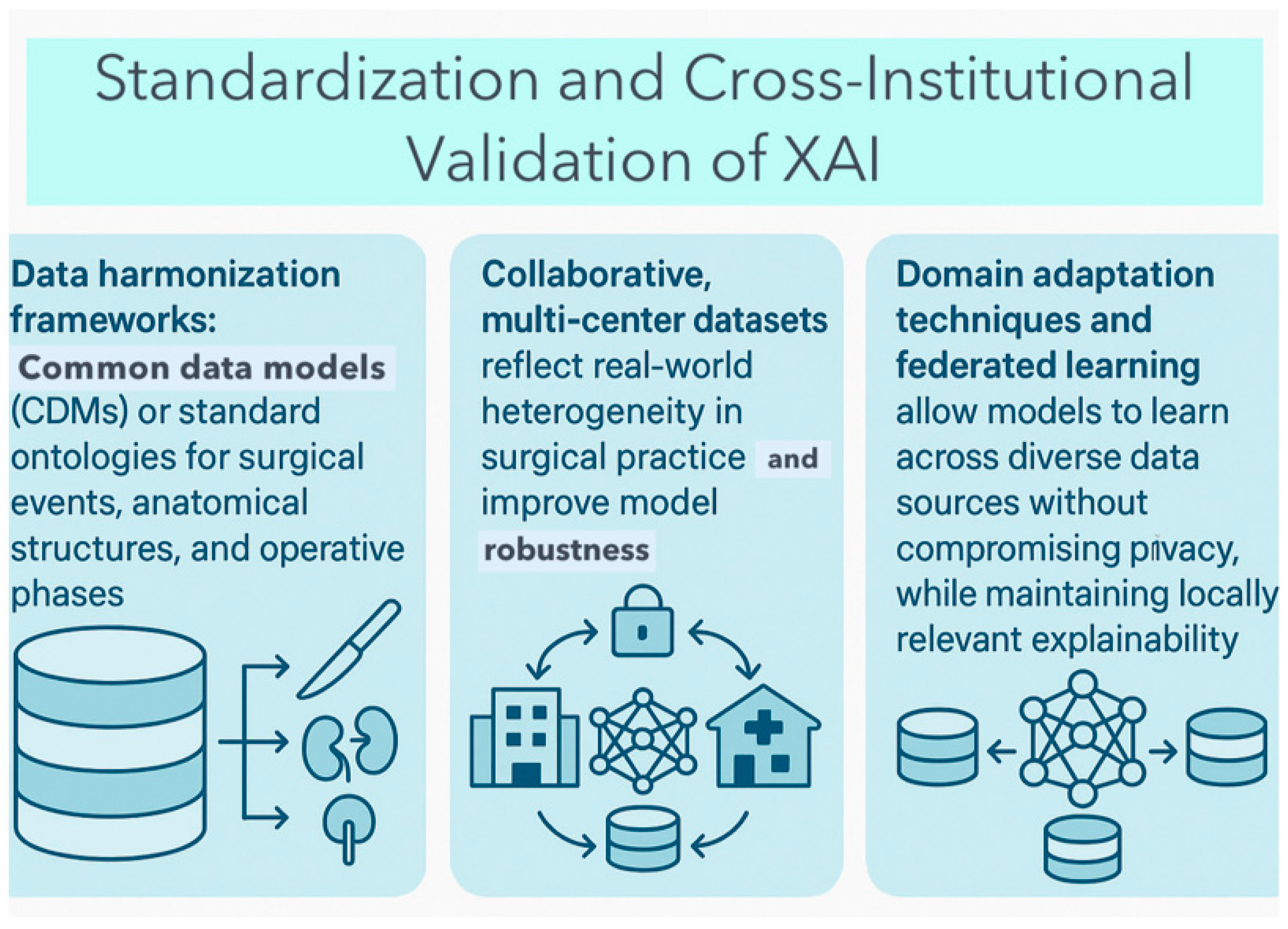

3.1. Definitions and Principles

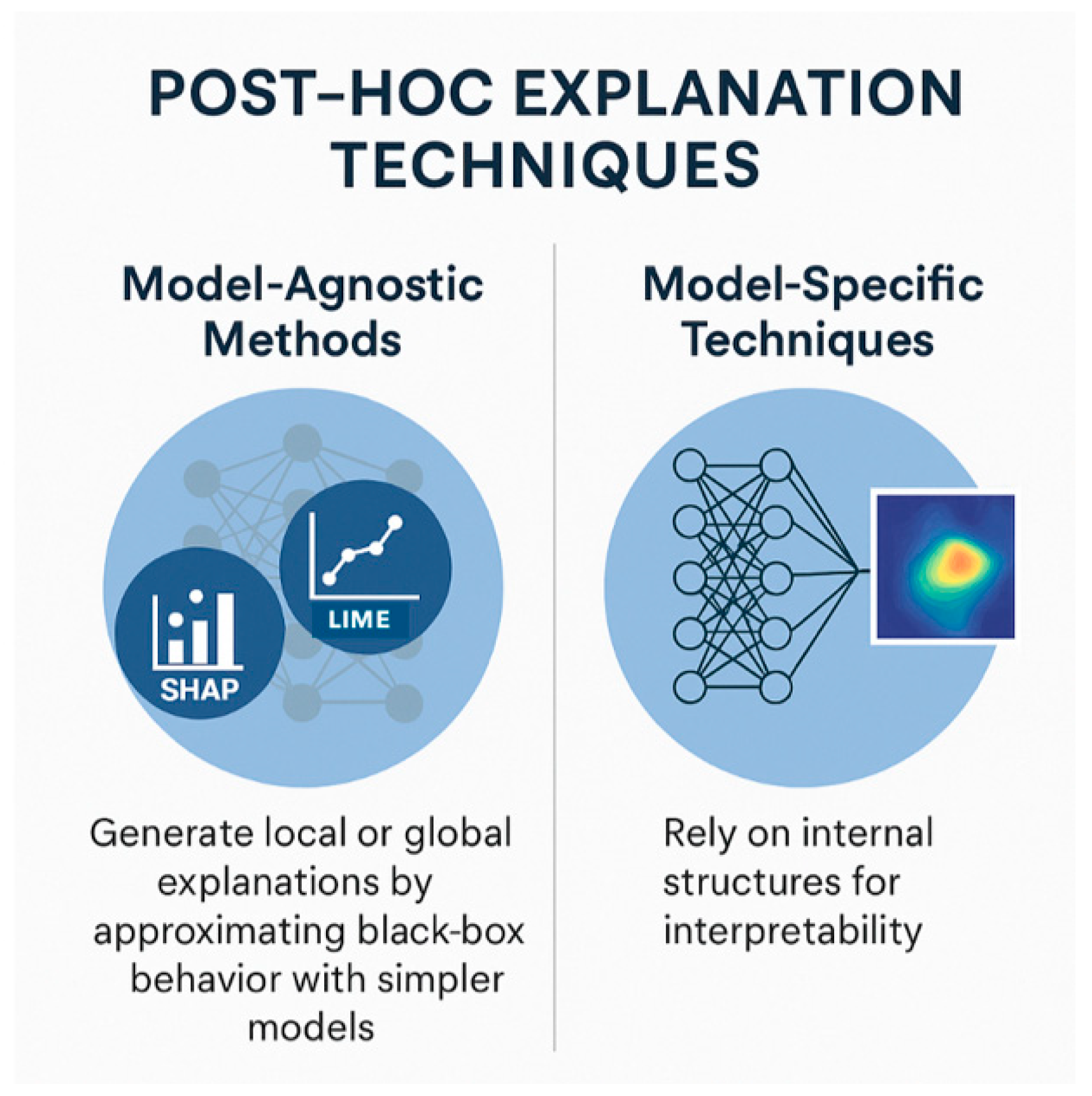

3.2. Key XAI Techniques Used in Surgery

3.3. Unique Challenges in the Surgical Domain

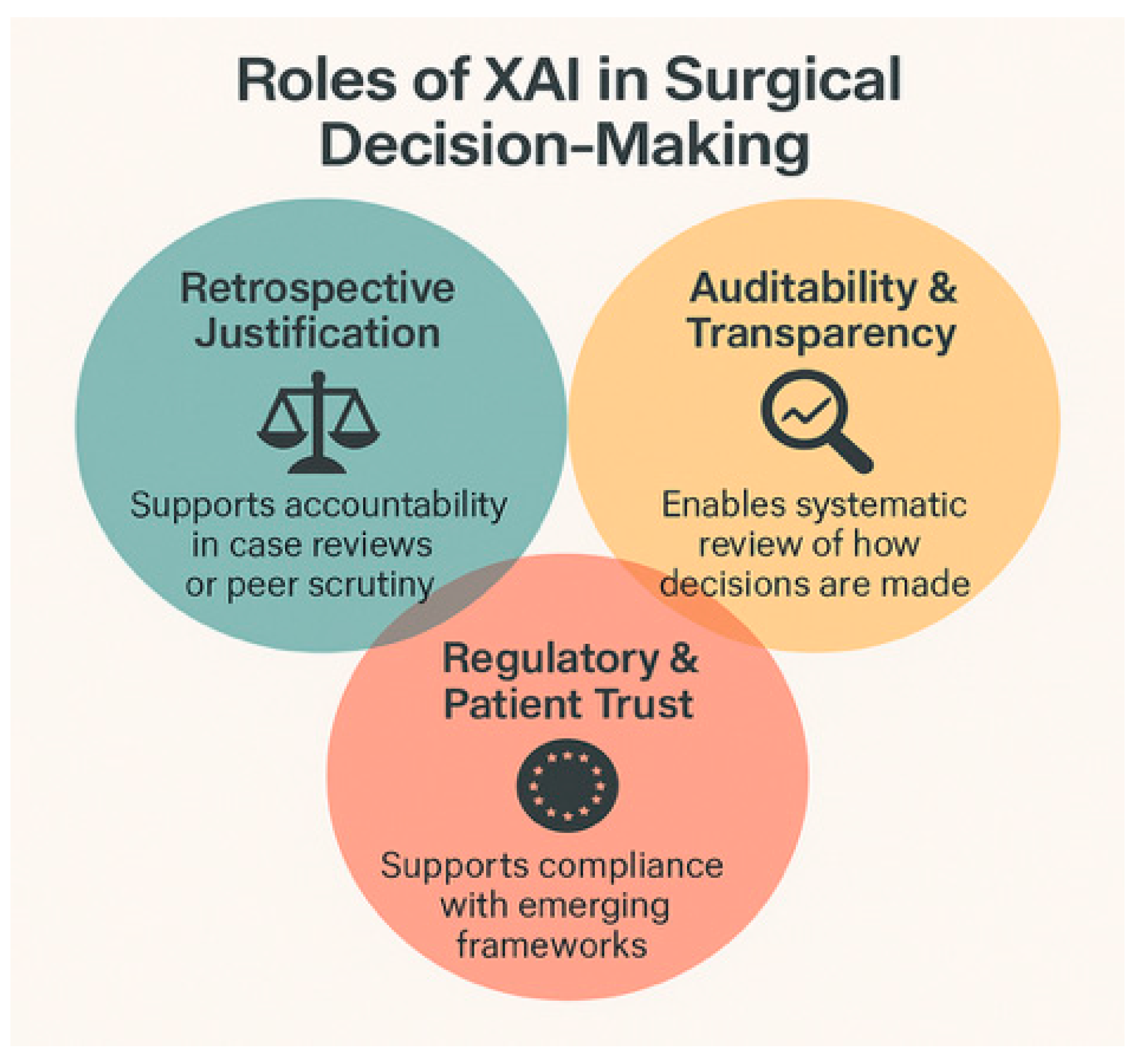

4. Ethical and Legal Imperatives for Explainable AI in Surgery

4.1. Accountability and Responsibility

4.2. Surgical Autonomy and Clinical Judgment

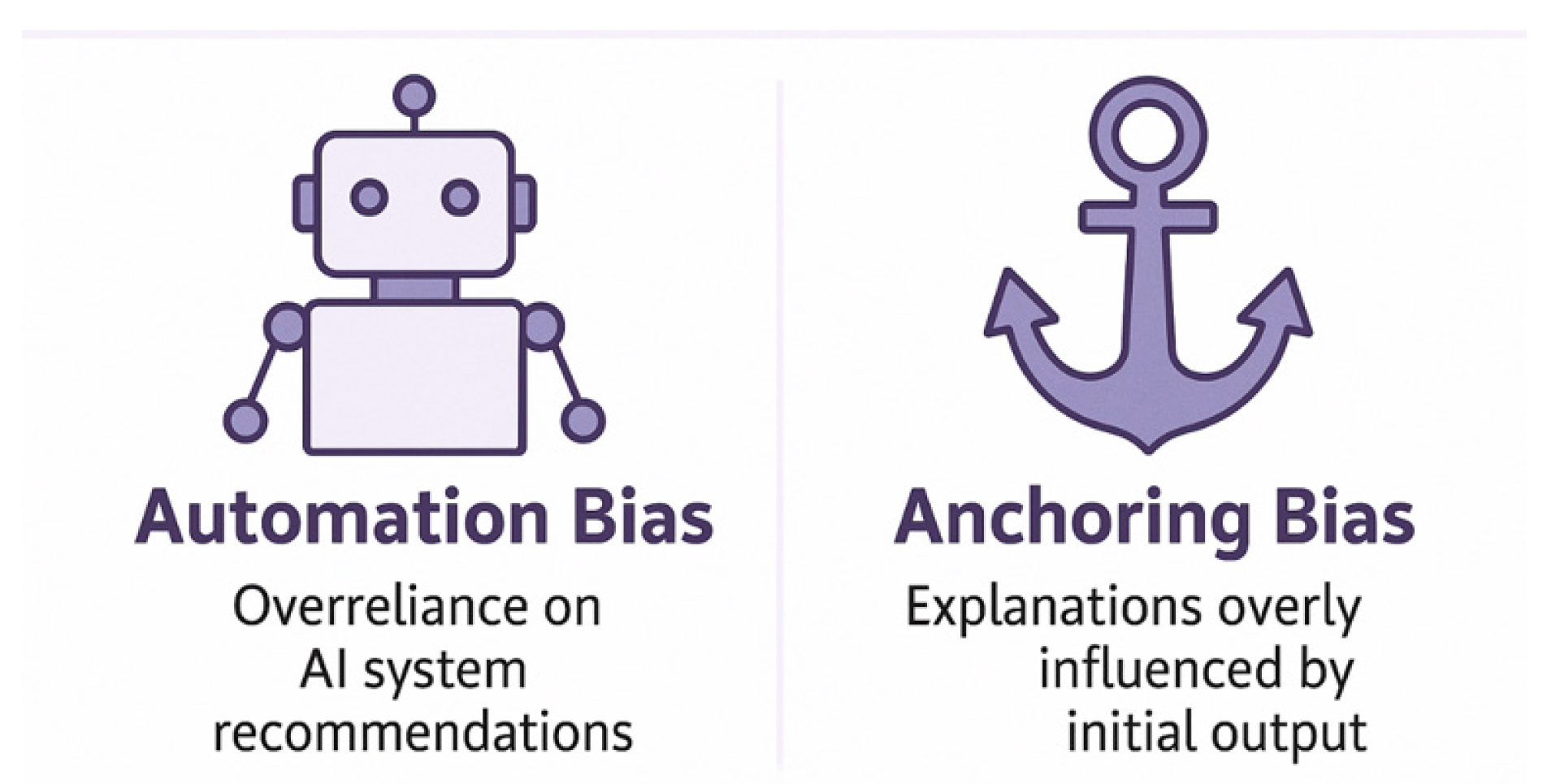

4.3. Informed Consent and Shared Decision-Making

4.4. Equity and Bias Detection

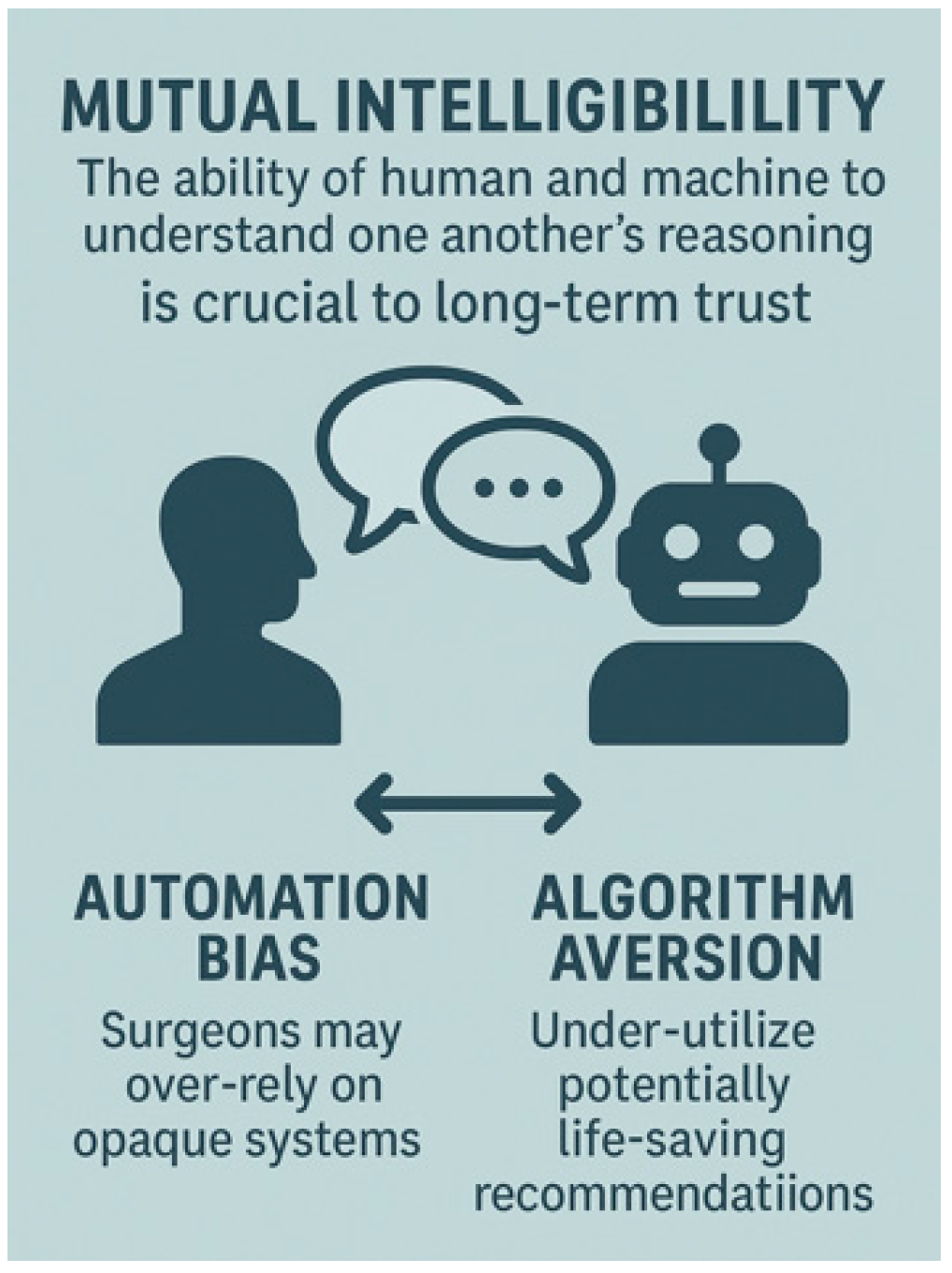

4.5. Trust and Team Dynamics

5. Clinical Applications of Explainable AI in Surgery

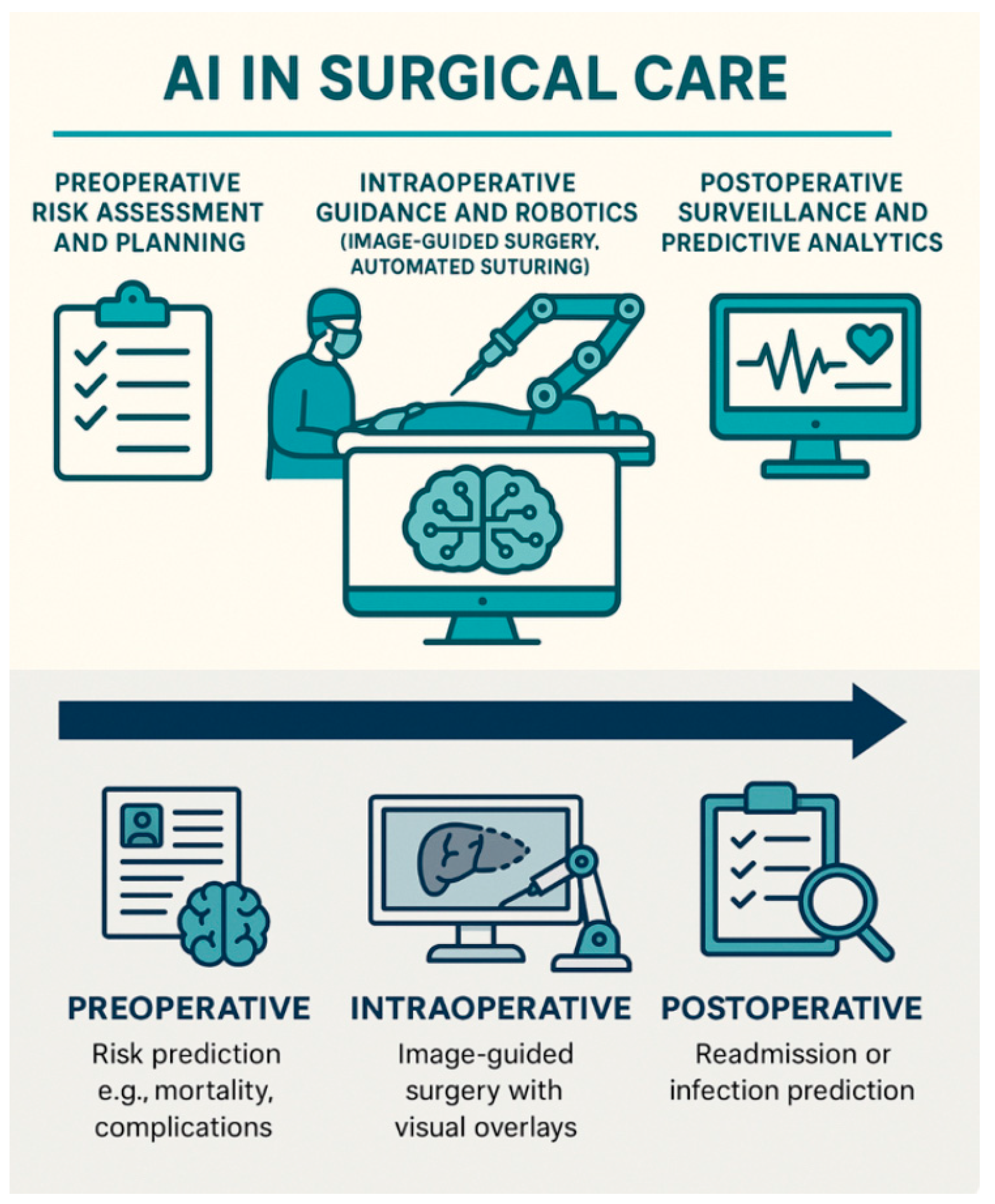

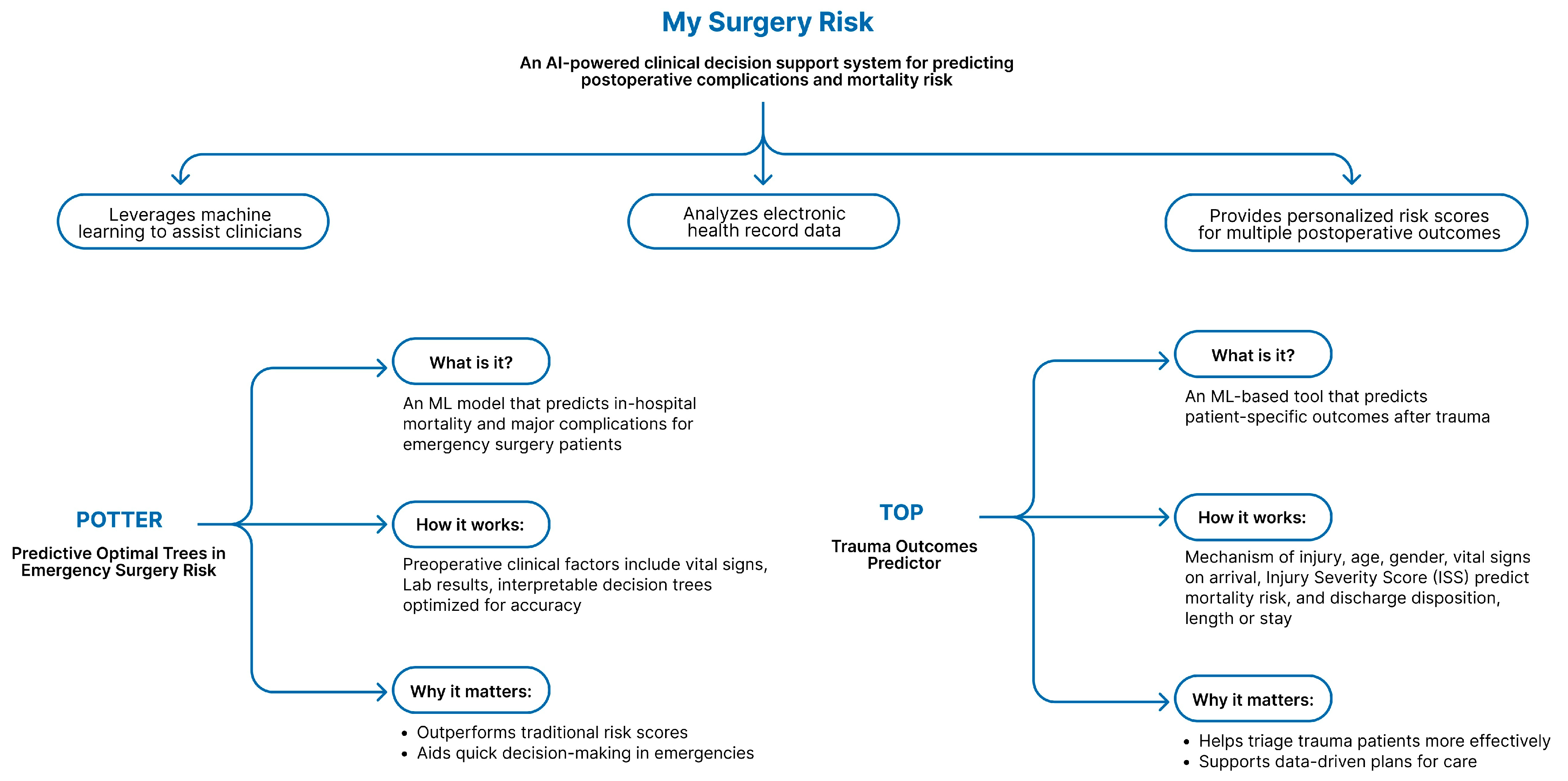

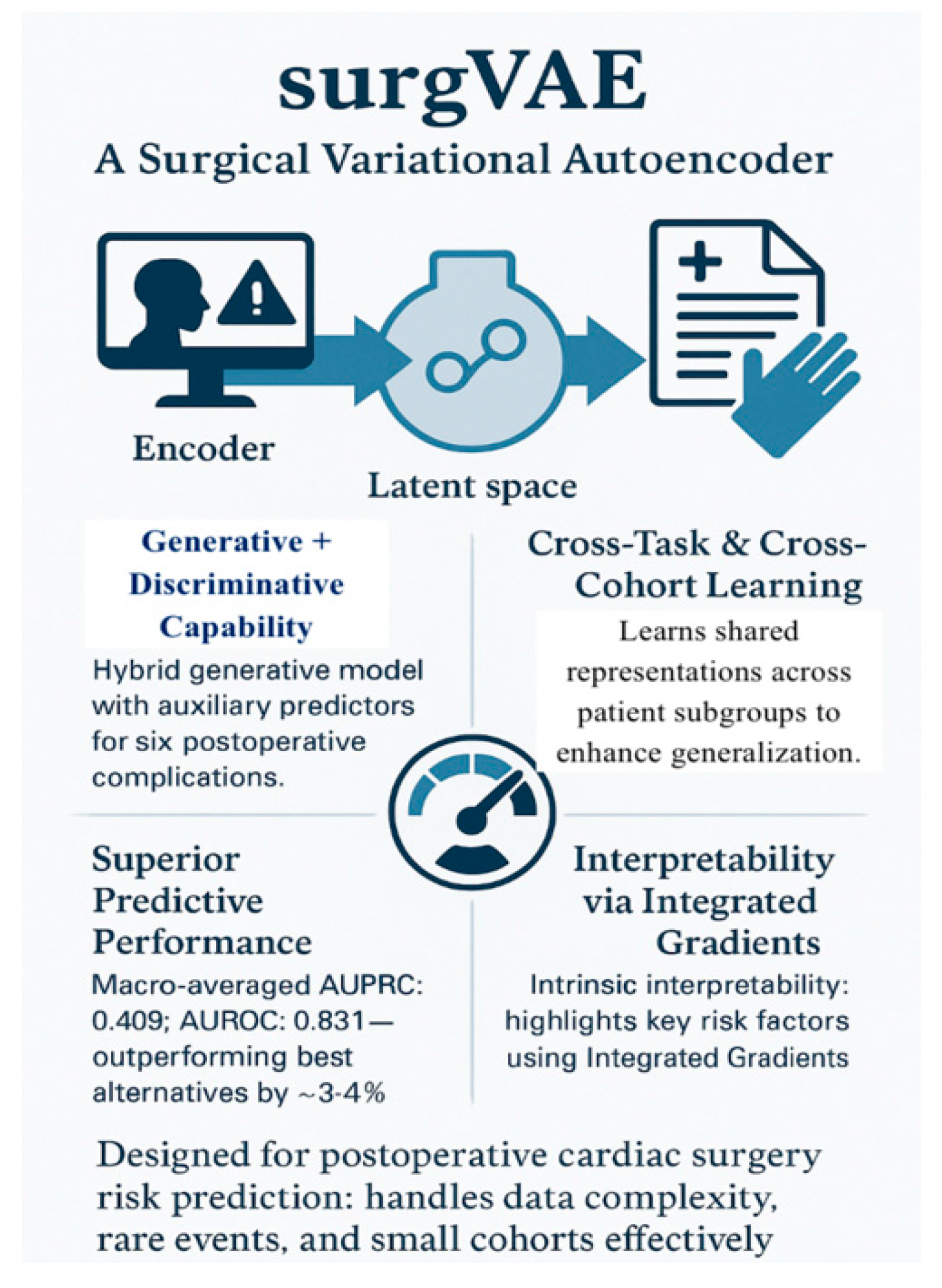

5.1. Preoperative Phase-Risk Prediction

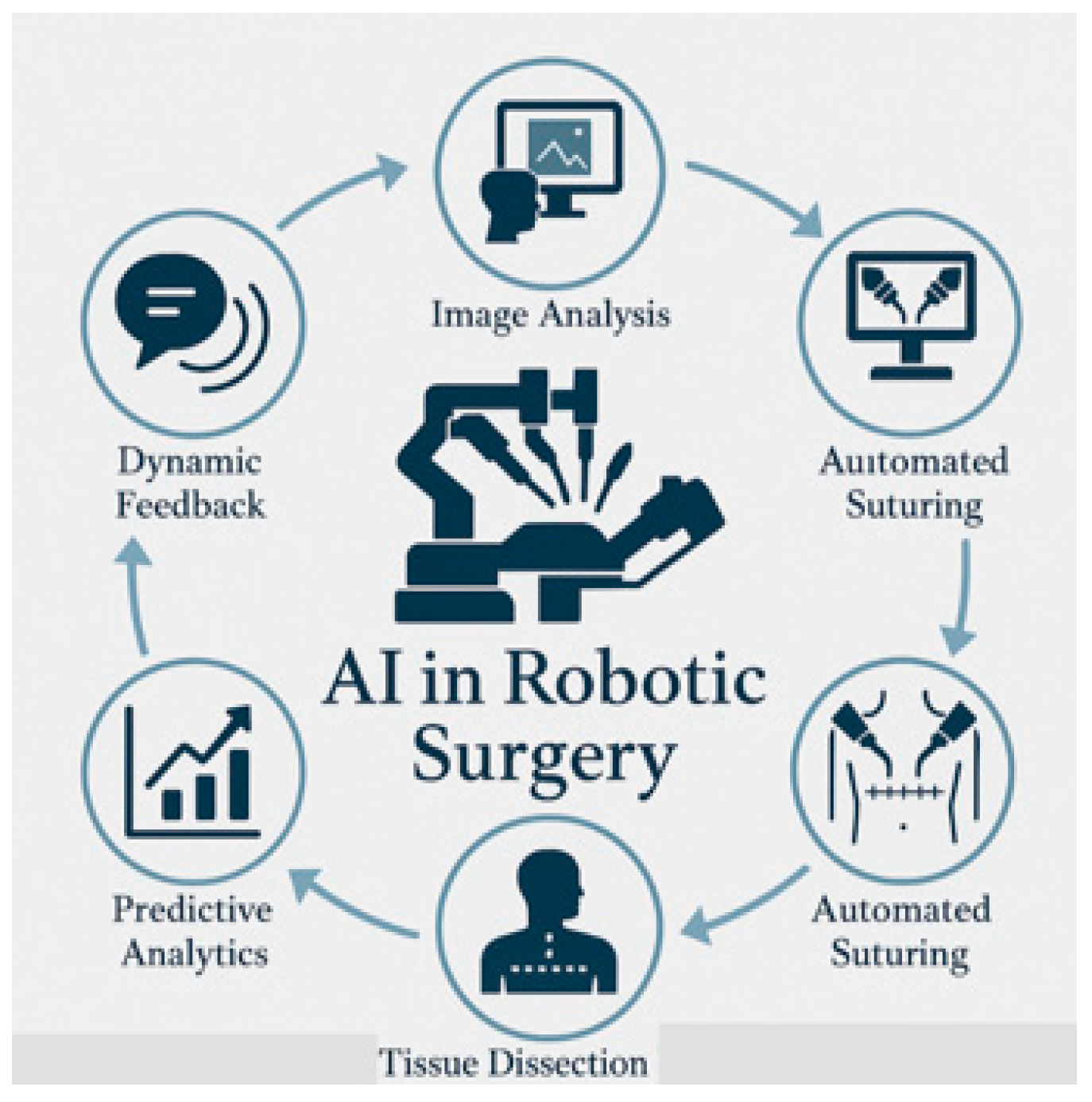

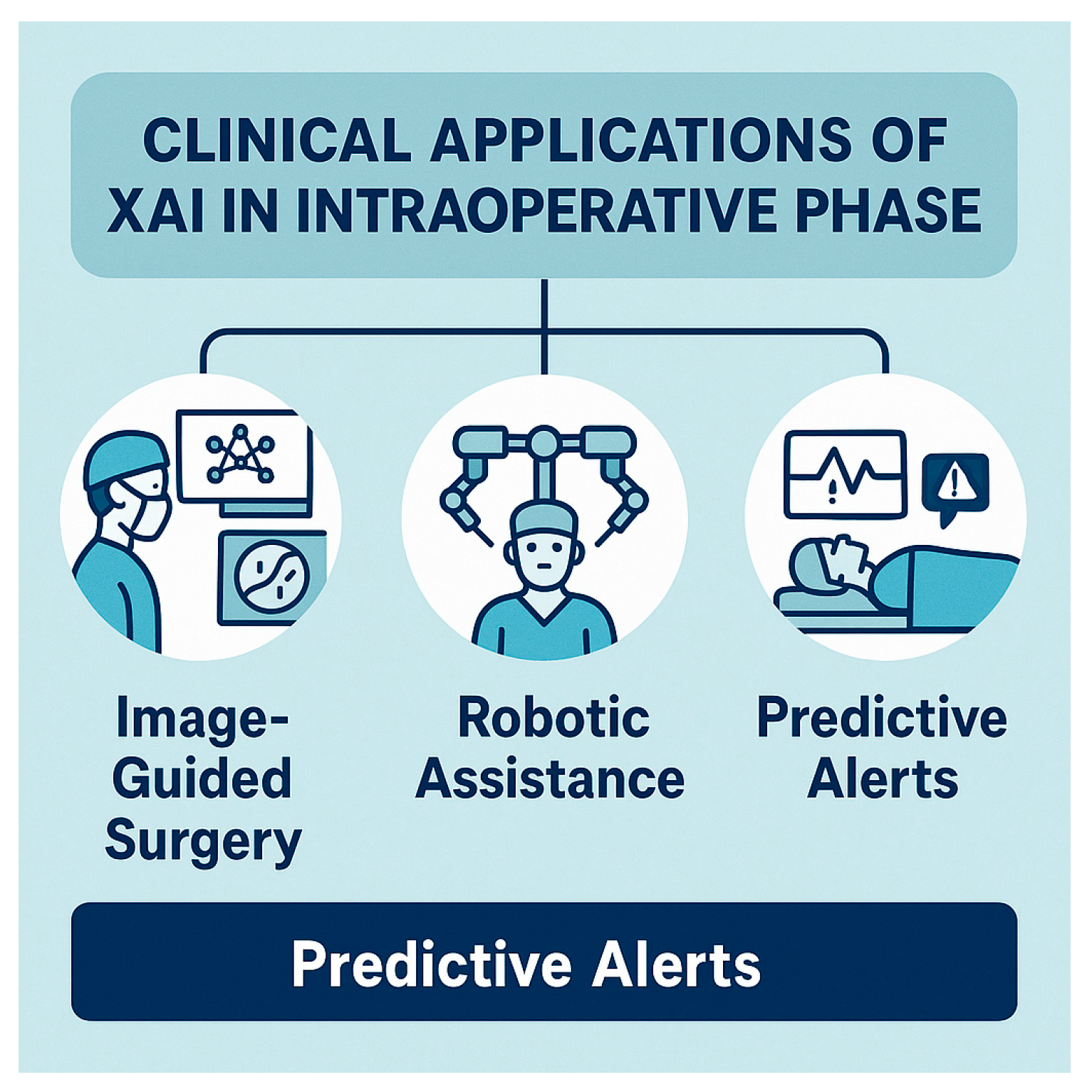

5.2. Intraoperative Phase

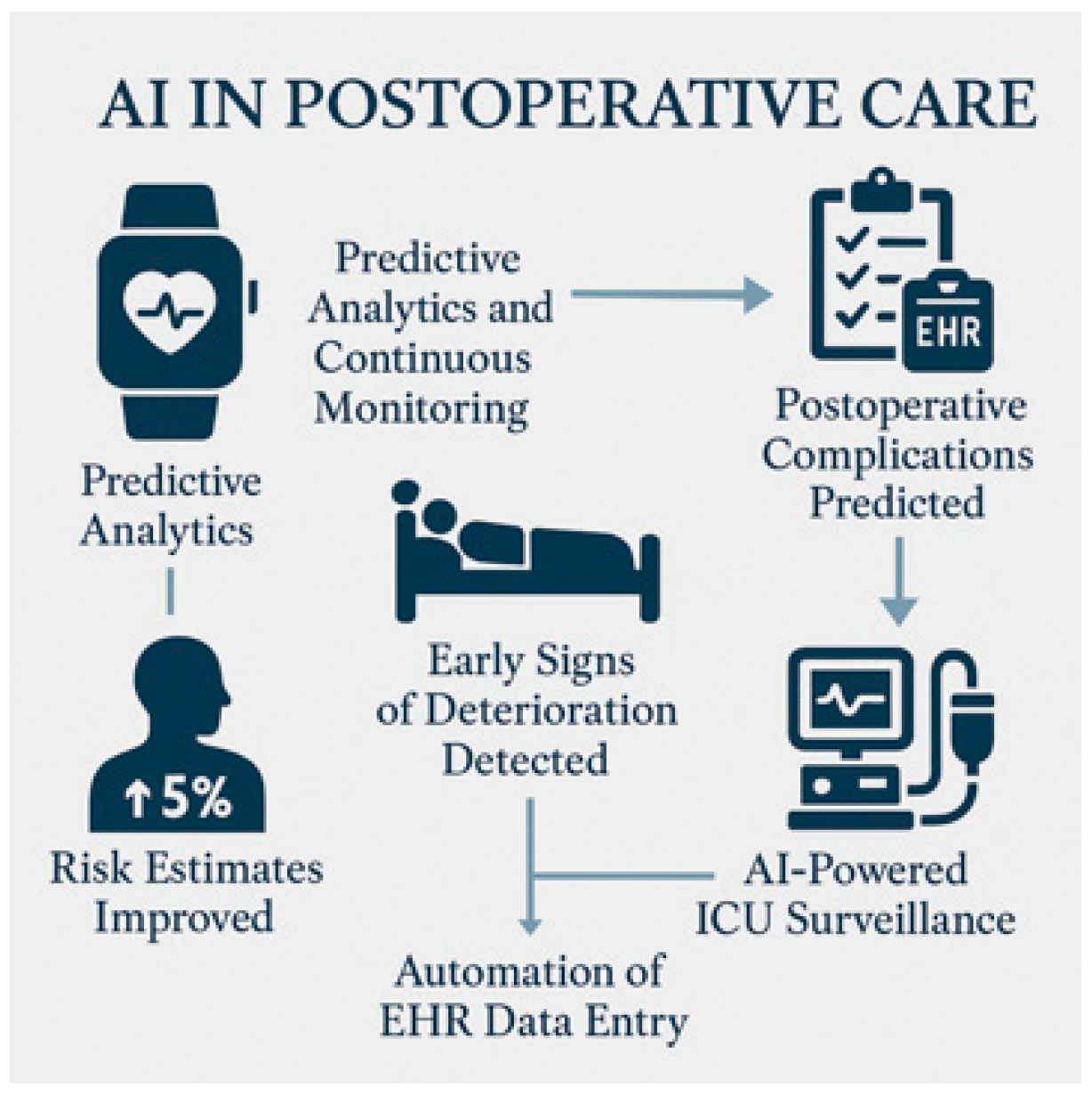

5.3. Postoperative Monitoring and Outcomes

5.4. Training and Simulation

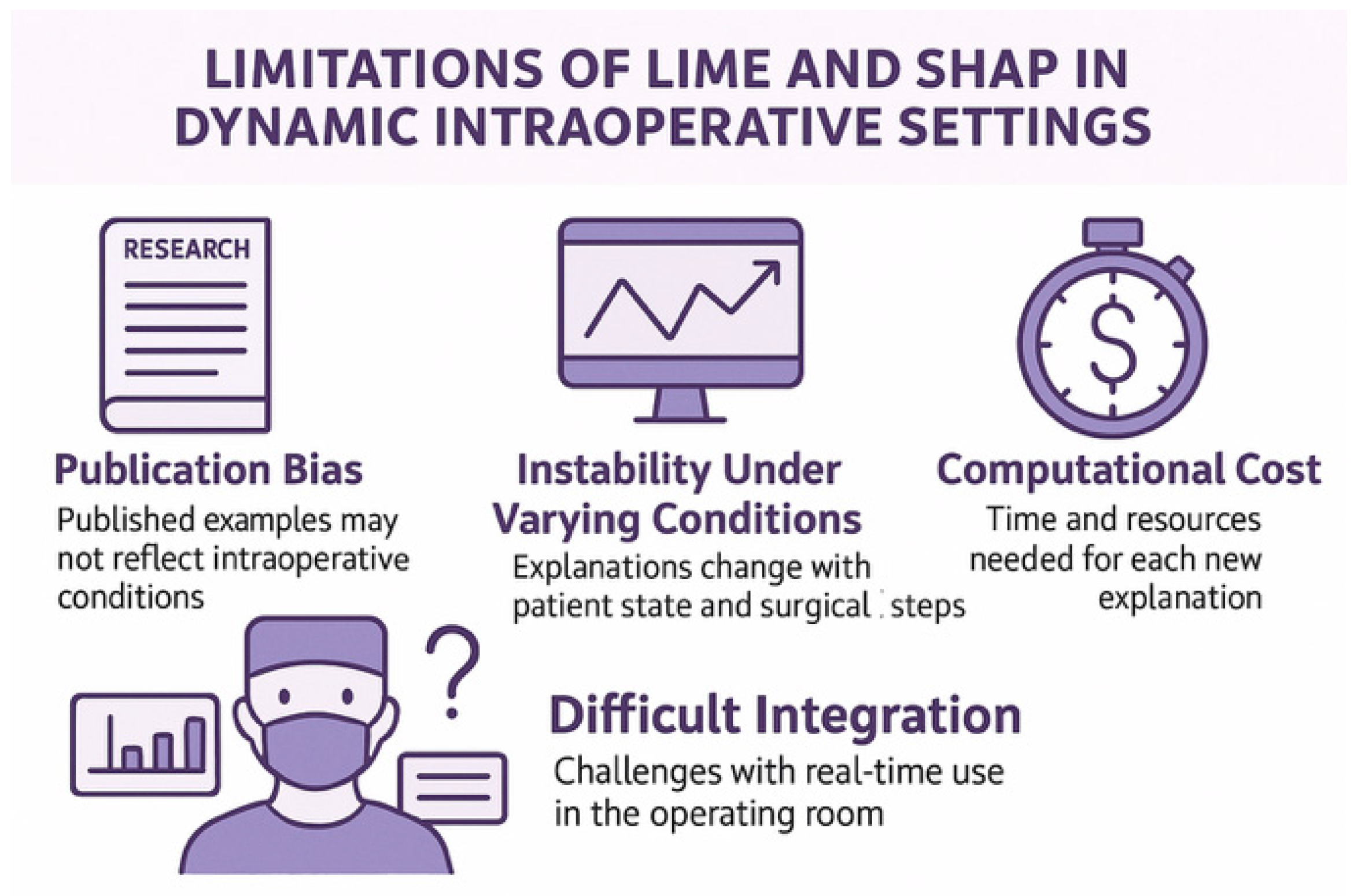

6. Technical Considerations and Limitations

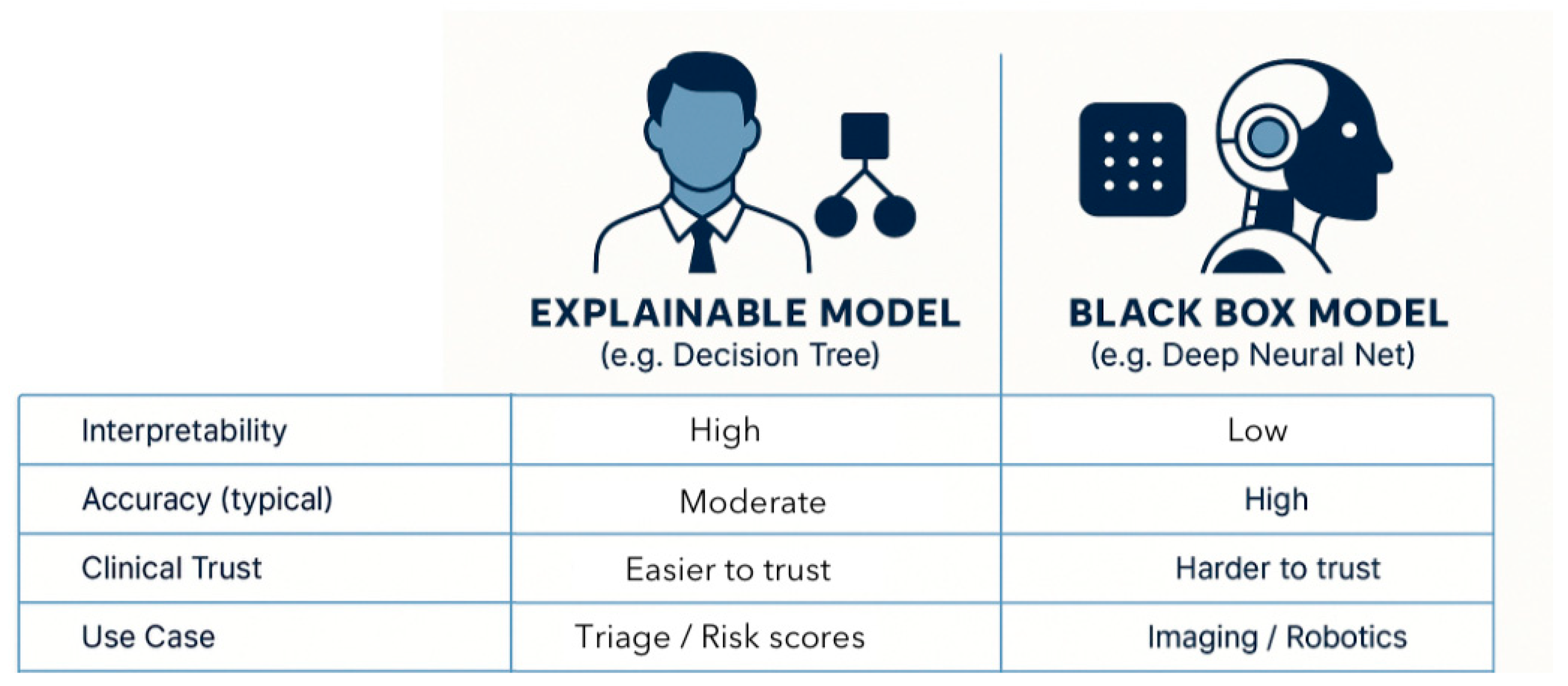

6.1. The Accuracy–Explainability Trade-Off

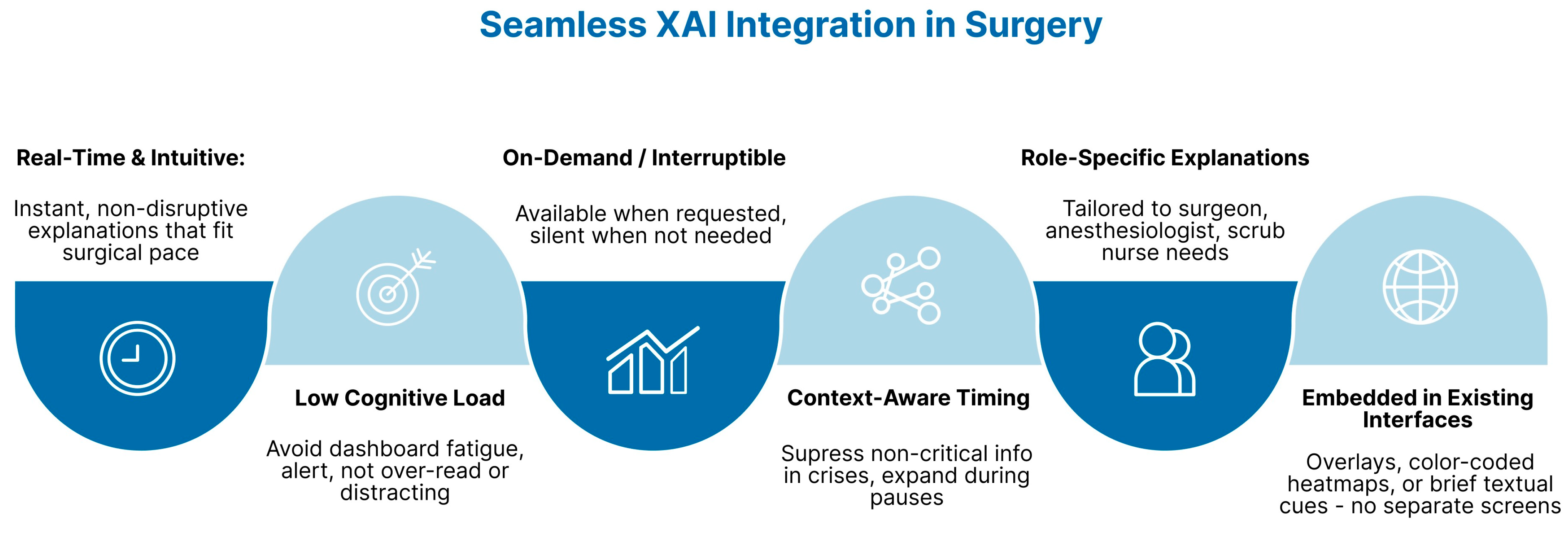

6.2. Workflow Integration

6.3. Misleading Explanations

6.4. Data Heterogeneity and Generalizability

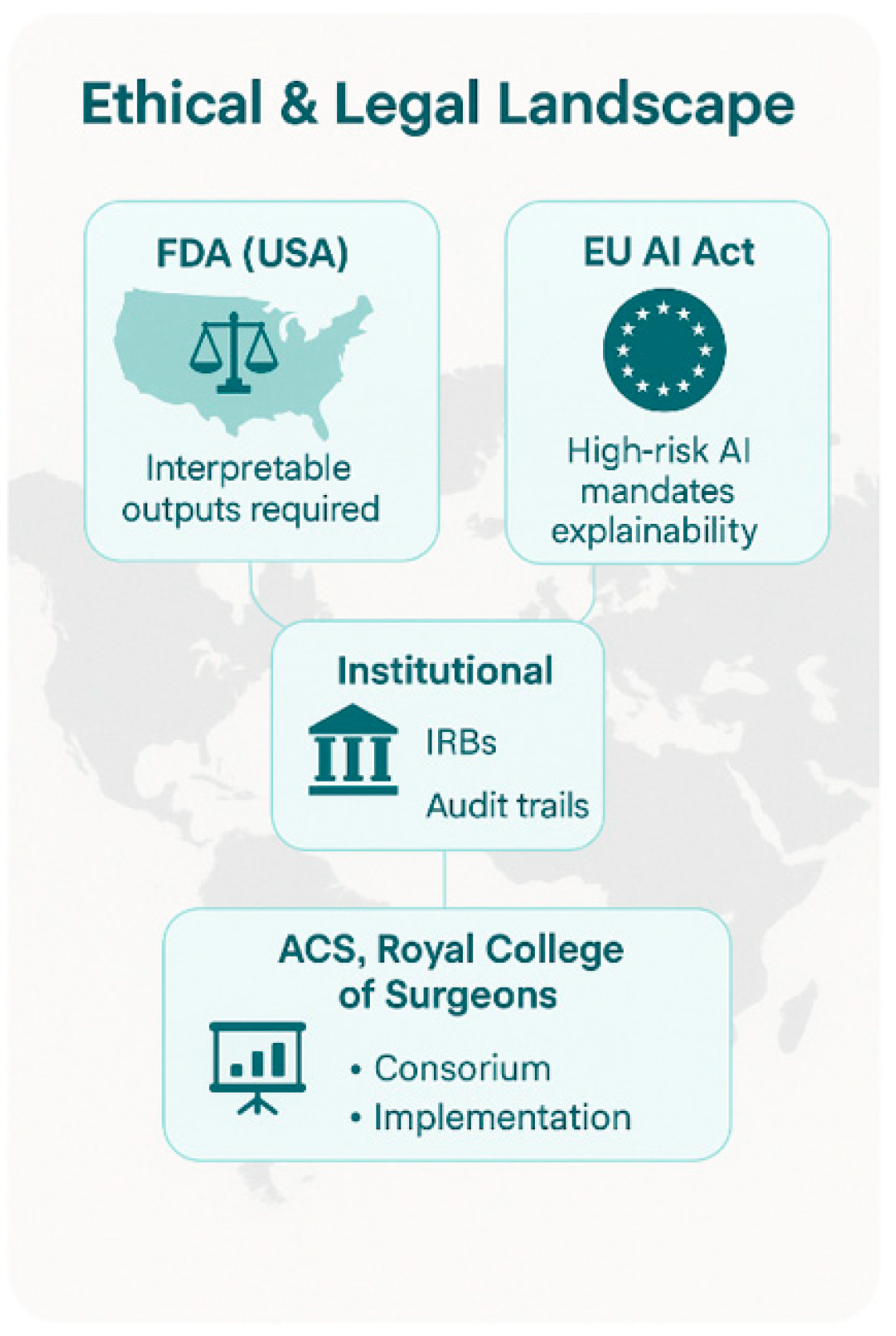

7. Regulatory and Institutional Context

7.1. Global Regulatory Landscape

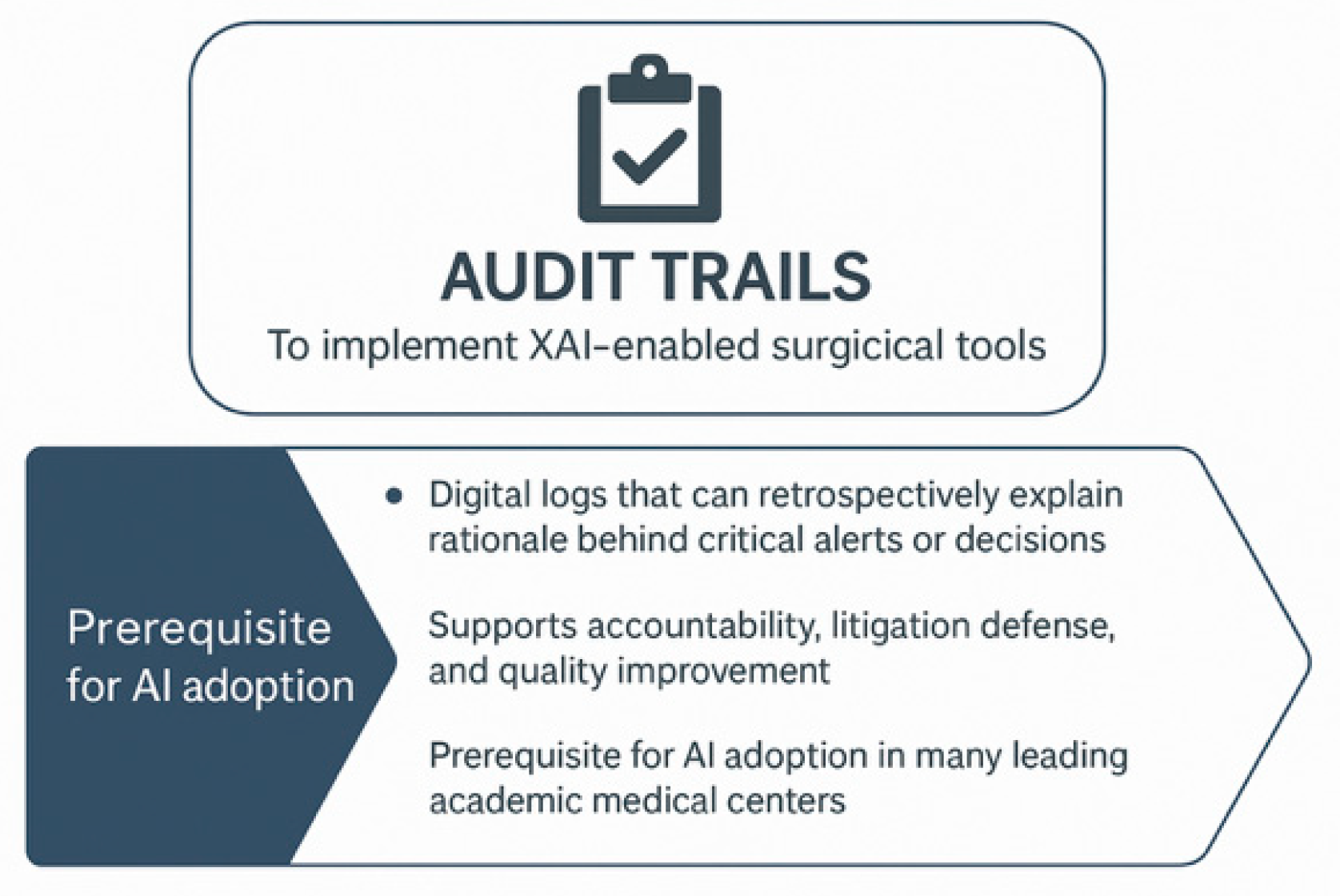

7.2. Institutional Ethics and Oversight

7.3. Guidelines from Surgical Societies

7.4. AI Model Validation

8. Future Directions and Recommendations

8.1. Human-Centered XAI Design

8.2. Real-Time and Interactive XAI

8.3. Validation, Benchmarking, and Reporting

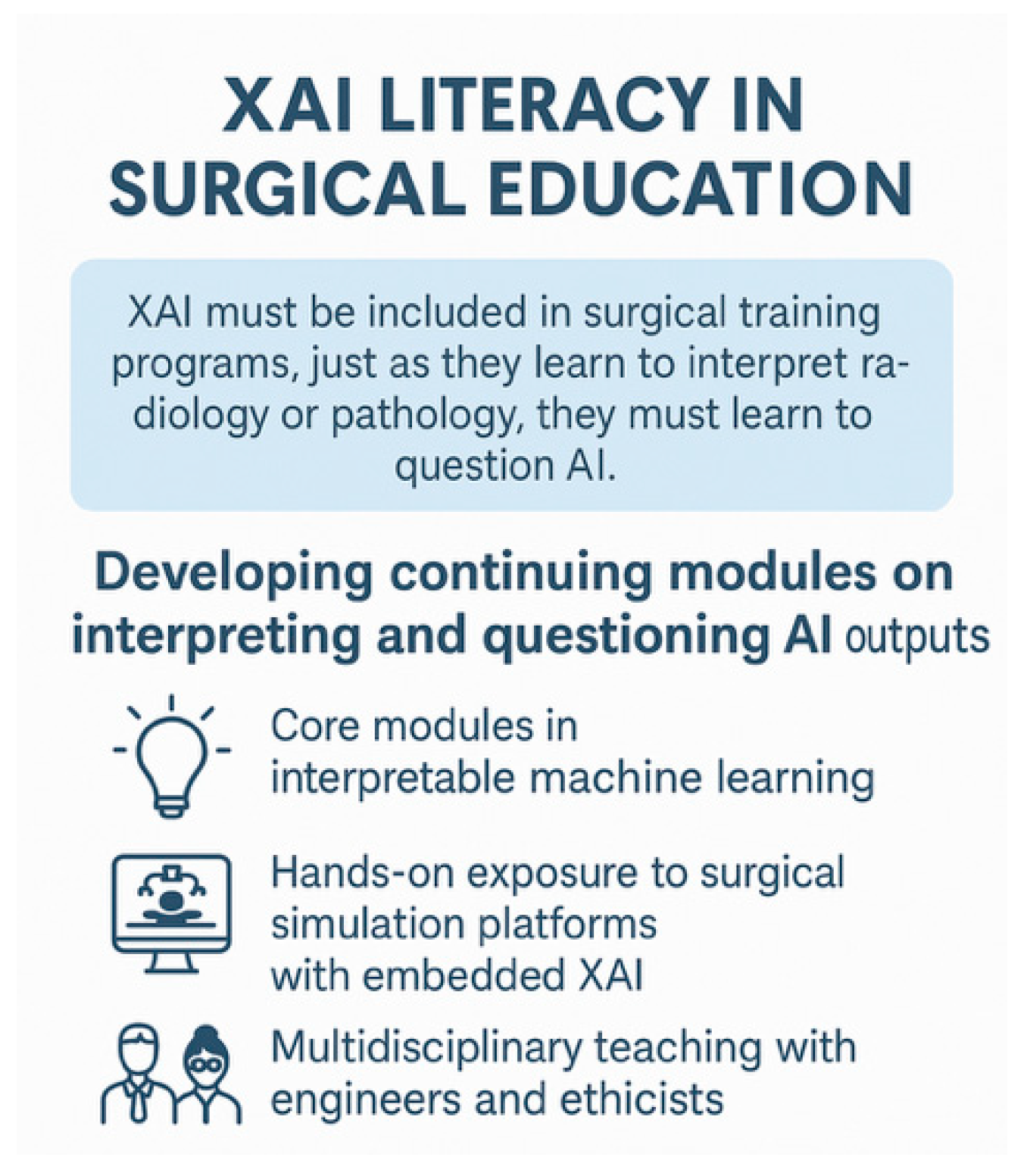

8.4. Education and Skills Development

9. Discussion

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saraiva, M.M.; Ribeiro, T.; Agudo, B.; Afonso, J.; Mendes, F.; Martins, M.; Cardoso, P.; Mota, J.; Almeida, M.J.; Costa, A.; et al. Evaluating ChatGPT-4 for the Interpretation of Images from Several Diagnostic Techniques in Gastroenterology. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dang, F.; Samarasena, J.B. Generative Artificial Intelligence for Gastroenterology: Neither Friend nor Foe. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 2146–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirosawa, T.; Kawamura, R.; Harada, Y.; Mizuta, K.; Tokumasu, K.; Kaji, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Shimizu, T. ChatGPT-Generated Differential Diagnosis Lists for Complex Case-Derived Clinical Vignettes: Diagnostic Accuracy Evaluation. JMIR Med. Inform. 2023, 11, e488084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoda, Y.; Kurokawa, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Kanzawa, J.; Kurokawa, M.; Ohizumi, Y.; Gonoi, W.; Abe, O. Diagnostic performances of GPT-4o, Claude 3 Opus, and Gemini 1.5 Pro in “Diagnosis Please” cases. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2024, 42, 1231–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henson, J.B.; Glissen Brown, J.R.; Lee, J.P.; Patel, A.; Leiman, D.A. Evaluation of the Potential Utility of an Artificial Intelligence Chatbot in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Management. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 2276–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorelik, Y.; Ghersin, I.; Arraf, T.; Ben-Ishay, O.; Klein, A.; Khamaysi, I. Using a customized GPT to provide guideline-based recommendations for management of pancreatic cystic lesions. Endosc. Int. Open 2024, 12, E600–E603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javan, R.; Kim, T.; Mostaghni, N. GPT-4 Vision: Multi-Modal Evolution of ChatGPT and Potential Role in Radiology. Cureus 2024, 16, e68298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehdab, R.; Brendlin, A.; Werner, S.; Almansour, H.; Gassenmaier, S.; Brendel, J.M.; Nikolaou, K.; Afat, S. Evaluating ChatGPT-4V in chest CT diagnostics: A critical image interpretation assessment. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2024, 42, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifai, N.; van Doorn, R.; Malvehy, J.; Sangers, T.E. Can ChatGPT vision diagnose melanoma? An exploratory diagnostic accuracy study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, 1057–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinakis, S.; Kritsotakis, E.I.; Lasithiotakis, K. Artificial Intelligence in Surgical Risk Prediction. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chevalier, O.; Dubey, G.; Benkabbou, A.; Majbar, M.A.; Souadka, A. Comprehensive overview of artificial intelligence in surgery: A systematic review and perspectives. Pflugers Arch. 2025, 477, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.Y.; Wang, J.J.; Huang, S.H.; Kuo, C.-L.; Chen, J.-Y.; Liu, C.-F.; Chu, C.-C. Implementation of a machine learning application in preoperative risk assessment for hip repair surgery. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022, 22, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, M.; Ueda, D.; Matsumoto, T.; Shinkawa, H.; Yamamoto, A.; Shiba, M.; Okada, T.; Tani, N.; Tanaka, S.; Kimura, K.; et al. Deep Learning Model Based on Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography Imaging to Predict Postoperative Early Recurrence after the Curative Resection of a Solitary Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Yang, S.-Y.; Chai, J.-W.; Chen, W.-H.; Chang, P.-Y. Mortality Evaluation and Life Expectancy Prediction of Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Data Mining. Healthcare 2023, 11, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenig, N.; Monton Echeverria, J.; Muntaner Vives, A. Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: A Systematic Review of Use and Validation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karamitros, G.; Thayer, W.P.; Lamaris, G.A.; Perdikis, G.; Lineaweaver, W.C. Structural barriers and pathways to artificial intelligence integration in plastic surgery. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2025, 111, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Obaido, G.; Jere, N.; Mienye, E.; Aruleba, K.; Emmanuel, I.D.; Ogbuokiri, B. A Survey of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Concepts, Applications, and Challenges. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2024, 51, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Weng, Y.; Lund, J. Applications of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Diagnosis and Surgery. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metta, C.; Beretta, A.; Pellungrini, R.; Rinzivillo, S.; Giannotti, F. Towards Transparent Healthcare: Advancing Local Explanation Methods in Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brandenburg, J.M.; Müller-Stich, B.P.; Wagner, M.; van der Schaar, M. Can surgeons trust AI? Perspectives on machine learning in surgery and the importance of eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2025, 410, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Amann, J.; Blasimme, A.; Vayena, E.; Frey, D.; Madai, V.I. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: A multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkoum, H.; Idri, A.; Abnane, I. Global and local interpretability techniques of supervised machine learning black box models for numerical medical data. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 131, 107829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzmueller, M.; Fürnkranz, J.; Kliegr, T.; Schmid, U. Explainable and interpretable machine learning and data mining. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2024, 38, 2571–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Y.A.; Khoo, B.E.; Asaari, M.S.M.; Aziz, M.E.; Ghazali, F.R. Decoding the black box: Explainable AI (XAI) for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment planning-A state-of-the art systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2025, 193, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torda, T.; Ciardiello, A.; Gargiulo, S.; Grillo, G.; Scardapane, S.; Voena, C.; Giagu, S. Influence based explainability of brain tumors segmentation in magnetic resonance imaging. Prog. Artif. Intell. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, M.; Maurer, M.H.; Thomas, R.P. Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Radiological Cardiovascular Imaging—A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Yao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, S.; Cui, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Tian, H.; Ye, X.; et al. A new xAI framework with feature explainability for tumors decision-making in Ultrasound data: Comparing with Grad-CAM. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 235, 107527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topol, E. Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, M.; Mendes, F.; Martins, M.; Ribeiro, T.; Afonso, J.; Cardoso, P.; Ferreira, J.; Fonseca, J.; Macedo, G. Explainable AI in Digestive Healthcare and Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plass, M.; Kargl, M.; Kiehl, T.R.; Regitnig, P.; Geißler, C.; Evans, T.; Zerbe, N.; Carvalho, R.; Holzinger, A.; Müller, H. Explainability and causability in digital pathology. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2023, 9, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salih, A.; Sengupta, P.P. Explainable artificial intelligence and cardiac imaging. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 16, e014519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, T.; Haggenmueller, S.; Bucher, T.-C.; Holland-Letz, T.; Kittler, H.; Tschandl, P.; Heppt, M.V.; Berking, C.; Utikal, J.S.; Schilling, B.; et al. Dermatologist-like explainable AI enhances melanoma diagnosis accuracy: Eye-tracking study. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Nair, B.; Vavilala, M.S.; Horibe, M.; Eisses, M.J.; Adams, T.; Liston, D.E.; Low, D.K.-W.; Newman, S.-F.; Kim, J.; et al. Explainable machine-learning predictions for the prevention of hypoxaemia during surgery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Robicquet, A.; Ramsundar, B.; Kuleshov, V.; DePristo, M.; Chou, K.; Cui, C.; Corrado, G.; Thrun, S.; Dean, J. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Biemann, C.; Pattichis, C.S.; Kell, D.B. What do we need to build explainable AI systems for the medical domain? arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.09923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjoa, E.; Guan, C. A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Towards Medical XAI. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 32, 4793–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, S.; Minssen, T.; Cohen, G. Ethical and legal challenges of artificial intelligence-driven healthcare. In Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Price, W.N.I.I.; Gerke, S.; Cohen, I.G. Potential liability for physicians using artificial intelligence. JAMA 2019, 322, 1765–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.H.; Kohane, I.S. Framing the challenges of artificial intelligence in medicine. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2019, 28, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.; Swetlitz, I. IBM’s Watson supercomputer recommended “unsafe and incorrect” cancer treatments, internal documents show. Stat News. 2018, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation Laying Down Harmonised Rules on Artificial Intelligence (AI Act). 2021. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/proposal-regulation-laying-down-harmonised-rules-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Challen, R.; Denny, J.; Pitt, M.; Gompels, L.; Edwards, T.; Tsaneva-Atanasova, K. Artificial intelligence, bias and clinical safety. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2019, 28, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.; Floridi, L. An ethically mindful approach to AI for health care. Lancet Digit Health 2020, 395, 254–255. [Google Scholar]

- Holzinger, A.; Langs, G.; Denk, H.; Zatloukal, K.; Müller, H. Causability and explainability of AI in medicine. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2019, 9, e1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4765–4774. [Google Scholar]

- Wachter, S.; Mittelstadt, B.; Russell, C. Counterfactual explanations without opening the black box: Automated decisions and the GDPR. Harv. J. Law Technol. 2018, 31, 841–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiera, E. The forgetting health system. Learn Health Syst. 2017, 1, e10023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.H.; Beam, A.L.; Kohane, I.S. Artificial intelligence in healthcare. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 2, 719–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London, A.J. Artificial intelligence and black-box medical decisions: Accuracy versus explainability. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2019, 49, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, M.; Oakden-Rayner, L.; Beam, A.L. The false hope of current approaches to explainable artificial intelligence in health care. Lancet Digit Health 2021, 3, e745–e750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortliffe, E.H.; Sepúlveda, M.J. Clinical decision support in the era of artificial intelligence. JAMA 2018, 320, 2199–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longoni, C.; Bonezzi, A.; Morewedge, C.K. Resistance to medical artificial intelligence. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 629–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonekaboni, S.; Joshi, S.; McCradden, M.D.; Goldenberg, A. What clinicians want: Contextualizing explainable machine learning for clinical end use. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.05134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Lee, S.I. Consistent individualized feature attribution for tree ensembles. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03888. [Google Scholar]

- Vayena, E.; Blasimme, A.; Cohen, I.G. Machine learning in medicine: Addressing ethical challenges. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Powers, B.; Vogeli, C.; Mullainathan, S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 2019, 366, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, A.H.; Scott, V.K.; Rehman, K.A.; Velopulos, C.; Bentley, J.M.; Cornwell, E.E.; Al-Refaie, W. Racial disparities in surgical care and outcomes in the United States: A comprehensive review. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2013, 216, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkomar, A.; Hardt, M.; Howell, M.D.; Corrado, G.; Chin, M.H. Ensuring fairness in machine learning to advance health equity. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.Y.; Joshi, S.; Ghassemi, M. Treating health disparities with artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyyed-Kalantari, L.; Zhang, H.; McDermott, M.; Chen, I.Y.; Ghassemi, M. Underdiagnosis bias of artificial intelligence algorithms applied to chest radiographs in under-served patient populations. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 2176–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.; Saria, S.; Sendak, M.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, V.X.; Doshi-Velez, F.; Jung, K.; Heller, K.; Kale, D.; Saeed, M.; et al. Do no harm: A roadmap for responsible machine learning for health care. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1337–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; Wu, S.; Zaldivar, A.; Barnes, P.; Vasserman, L.; Hutchinson, B.; Spitzer, E.; Raji, I.D.; Gebru, T. Model cards for model reporting. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAT), Atlanta, GA, USA, 29–31 January 2019; pp. 220–229. [Google Scholar]

- Wachter, S.; Mittelstadt, B.; Russell, C. Why fairness cannot be automated: Bridging the gap between EU non-discrimination law and AI. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2021, 41, 105567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulas, S.; Karamitros, G. How to harness the power of web scraping for medical and surgical research: An application in estimating international collaboration. World J. Surg. 2024, 48, 1297–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzindolet, M.T.; Peterson, S.A.; Pomranky, R.A.; Pierce, L.G.; Beck, H.P. The role of trust in automation reliance. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2003, 58, 697–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elish, M.C. Moral crumple zones: Cautionary tales in human-robot interaction. Engag. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2019, 5, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendak, M.P.; D’Arcy, J.; Kashyap, S.; Gao, M.; Nichols, M.; Corey, K.; Ratliff, W. A path for translation of machine learning products into healthcare delivery. EMJ Innov. 2020, 10, 19-00172. [Google Scholar]

- Amann, J.; Vetter, D.; Blomberg, S.N.; Christensen, H.C.; Coffee, M.; Gerke, S.; Gilbert, T.K.; Hagendorff, T.; Holm, S.; Livne, M.; et al. To explain or not to ex-plain?—Artificial Intelligence Explainability in clinical decision support systems. PLoS Digit. Health 2022, 1, e0000016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahajan, A.; Esper, S.; Oo, T.H.; McKibben, J.; Garver, M.; Artman, J.; Klahre, C.; Ryan, J.; Sadhasivam, S.; Holder-Murray, J.; et al. Development and Validation of a Machine Learning Model to Identify Patients Before Surgery at High Risk for Postoperative Adverse Events. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2322285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd IV, T.; Tignanelli, C. Artificial intelligence in surgery—A narrative review. J. Med. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, M.; Celi, L.A.; Badawi, O.; Gordon, A.C.; Faisal, A.A. The artificial intelligence clinician learns optimal treatment strategies for sepsis in intensive care. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1716–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why should I trust you?”: Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

- Cizmic, A.; Mitra, A.T.; Preukschas, A.A.; Kemper, M.; Melling, N.T.; Mann, O.; Markar, S.; Hackert, T.; Nickel, F. Artificial intelligence for intraoperative video analysis in robotic-assisted esophagectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2025, 39, 2774–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, D.A.; Rosman, G.; Rus, D.; Meireles, O.R. Artificial intelligence in surgery: Promises and perils. Ann. Surg. 2018, 268, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leszczyńska, A.; Obuchowicz, R.; Strzelecki, M.; Seweryn, M. The Integration of Artificial Intelligence into Robotic Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasey, B.; Lippert, K.A.N.; Khan, D.Z.; Ibrahim, M.; Koh, C.H.; Layard Horsfall, H.; Lee, K.S.; Williams, S.; Marcus, H.J.; McCulloch, P. Intraoperative Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Robotic Surgery: A Scoping Review of Current Development Stages and Levels of Autonomy. Ann. Surg. 2023, 278, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Riva-Cambrin, H.A.; Singh, R.; Lama, S.; Sutherland, G.R. Liquid white box model as an explainable AI for surgery. Npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.C.; Chen, C.; Nguyen, A.; Choong, K.; Carlin, C.; Nelson, R.A.; Rossi, L.A.; Seth, N.; McNeese, K.; Yuh, B.; et al. Explainable Machine Learning Model to Preoperatively Predict Postoperative Complications in Inpatients With Cancer Undergoing Major Operations. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2024, 8, e2300247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Lopez, V.; Rihuete-Carpio, R.; Herrero-Sánchez, A.; Gavara, C.G.; Goh, B.K.; Koh, Y.X.; Paul, S.J.; Hilal, M.A.; Mishima, K.; Krürger, J.A.P.; et al. Explainable artificial intelligence prediction-based model in laparoscopic liver surgery for segments 7 and 8. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 2411–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Wu, Z.; Liang, P.; Luo, Z.; Kong, J.; Huang, J.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prediction model for postoperative pulmonary complications after thoracoscopic surgery with machine learning algorithms and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). J. Thorac. Dis. 2025, 17, 3603–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransvea, P.; Fransvea, G.; Liuzzi, P.; Sganga, G.; Mannini, A.; Costa, G. Study and validation of an explainable machine learning–based mortality prediction following emergency surgery in the elderly: A prospective observational study (FRAILESEL). Int. J. Surg. 2022, 107, 106954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Veerapong, J.; Fournier, K.F.; Johnston, F.M.; Dineen, S.P.; Powers, B.D.; Hendrix, R.; Lambert, L.A.; et al. Development and Validation of an Explainable Machine Learning Model for Major Complications After Cytoreductive Surgery. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2212930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Hu, Y.; Shu, L.; Li, J.; Duan, H.; Shu, Q.; Li, H. Explainable machine-learning predictions for complications after pediatric congenital heart surgery. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabian, H.; Alshirbaji, T.A.; Jalal, N.A.; Krueger-Ziolek, S.; Moeller, K. P-CSEM: An Attention Module for Improved Laparoscopic Surgical Tool Detection. Sensors 2023, 23, 7257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozuka, K.; Toruida, S.; Fujinaga, A.; Nakanuma, H.; Kawamura, M.; Matsunobu, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Kamiyama, T.; Ebe, K.; Endo, Y.; et al. Artificial intelligence software available for medical devices: Surgical phase recognition in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 46, 7444–7452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, D.A.; Rosman, G.; Witkowski, E.R. Computer Vision Analysis of Intraoperative Video: Automated Recognition of Operative Steps in Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Ann. Surg. 2019, 270, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madani, A.; Namazi, B.; Altieri, M.S.; Hashimoto, D.A.; Rivera, A.M.; Pucher, P.H.; Navarrete-Welton, A.; Sankaranarayanan, G.; Brunt, L.M.; Okrainec, A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for Intraoperative Guidance: Using Semantic Segmentation to identify surgical anatomy during Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Ann. Surg. 2022, 276, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, A.; Essa, I. Automated surgical skill assessment in RMIS training. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2018, 13, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, I.; Mees, S.T.; Weitz, J.; Speidel, S. Video-based surgical skill assessment using 3D convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2019, 14, 1217–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Iqbal, F.M.; Darzi, A.; Lo, B.; Purkayastha, S.; Kinross, J.M. MAchine Learning for technical skill assessment in surgery: A systematic review. npj Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascagni, P.; Alapatt, D.; Sestini, L. Computer vision in surgery: From potential to clinical value. npj Digi. Med. 2022, 5, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.K.; Chang, A.; Vincent, C.; Darzi, S.A. Development of assessing generic and specific technical skills in laparoscopic surgery. Am. J. Surg. 2006, 191, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, D.; Hilgard, S.; Jia, E.; Singh, S.; Lakkaraju, H. Fooling LIME and SHAP: Adversarial attacks on post hoc explanation methods. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, New York, NY, USA, 7–9 February 2020; pp. 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Sendak, M.P.; Ratliff, W.; Sarro, D.; Alderton, E.; Futoma, J.; Gao, M.; Nichols, M.; Revoir, M.; Yashar, F.; Miller, C.; et al. Real-world Integration of a sepsis Deep Learning Technology Into Routine Clinical Care: Implementation Study. JMIR MED Inform. 2020, 8, e15182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratwani, R.M.; Reider, J.; Singh, H. A decade of health information technology usability challenges and the path forward. JAMA 2019, 321, 743–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzinger, A.; Kieseberg, P.; Weippl, E.; Tjoa, A.M. Current advances, trends and challenges of machine learning and knowledge extraction: From machine learning to explainable AI. In Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11015, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Padoy, N. Machine and deep learning for workflow recognition during surgery. Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied Technol. 2019, 28, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): Action Plan. 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/145022/download (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- FDA Discussion Paper: Proposed Regulatory Framework for Modifications to AI/ML-Based Software as a Medical Device. 2021. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/medical%20devices/published/US-FDA-Artificial-Intelligence-and-Machine-Learning-Discussion-Paper.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Laux, J.; Watcher, S.; Mittelstadt, B. Trustworthy artificial intelligence and the European Union AI Act: On the conflation of trustworthiness and the acceptability of risk. Regul. Gov. 2024, 18, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, A.A.; Vardanyan, R.; Athanasiou, T.; Maessen, J.; Nia, P.S. The Ethical Considerations of integrating artificial intelligence into surgery: A review. Interdiscip. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2025, 40, ivae192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamitros, G.; Grant, M.P.; Lamaris, G.A. Associations in Medical Research Can Be Misleading: A Clinician’s Guide to Causal Inference. J. Surg. Res. 2025, 310, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Xue, B.; Kannampallil, T.; Lu, C.; Abraham, J. A Novel Generative Multi-Task Representation Learning Approach for Predicting Postoperative Complications in Cardiac Surgery Patients. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.01950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xue, B.; Kannampallil, T.; Lu, C.; Abraham, J. A novel generative multi-task representation learning approach for predicting postoperative complications in cardiac surgery patients. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2025, 32, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasey, B.; Nagendran, M.; Campbell, B.; Clifton, D.; Collins, G.S.; Denaxas, S.; Denniston, A.K.; Faes, L.; Geerts, B.; Ibrahim, M.; et al. Reporting guideline for the early-stage clinical evaluation of decision support systems driven by artificial intelligence: DECIDE-AI. BMJ 2022, 377, e070904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types of Generative AI | Applications in Medicine | |

|---|---|---|

| LLMs | Built primarily on transformer architectures (e.g., GPT-4). Trained on massive corpora of text, capable of generating coherent text, answering questions, or analyzing multimodal data (text + images). | Used for drafting reports, summarizing guidelines, providing decision support, and increasingly for exploratory image interpretation |

| GANs | Consist of a generator and a discriminator in competition. | Widely used in medical imaging for data augmentation (e.g., creating synthetic radiographs or histology slides), improving resolution, and reducing noise. |

| VAEs | Encode input into a latent space and reconstruct outputs. | Useful in anomaly detection and simulation of patient-specific scenarios (e.g., disease progression models). |

| Diffusion Models (Stable Diffusion, DALL.E-like systems) | Gradually denoise random noise to generate high-quality images. | Potential in medical imaging for reconstructing or enhancing diagnostic images. |

| Study/Year | Domain | Design/Setting | Performance | Agreement/Additional Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hirosawa et al. [3] Exploratory Internal Medicine Vignettes (2023) | Internal Medicine | Complex clinical vignettes; evaluated diagnostic accuracy | ChatGPT-4: 83% (10 differential diagnoses); 81% (5 differential diagnoses); 60% (final diagnosis)—comparable to internal medicine specialists | Comparable to human specialists in diagnostic reasoning |

| Sonoda et al. [4] Radiology Cases with ChatGPT-4 | Radiology | Case-based differential diagnosis task | 49.4% accuracy for the three-item differential diagnosis list | Suboptimal performance vs. expected radiology diagnostic standards |

| Henson et al. [5] GERD Recommendations (2023) | Gastroenterology (GERD) | Evaluation of ChatGPT recommendations for GERD management | 90% of chatbot recommendations were appropriate | Demonstrated safety and reliability in >90% of cases |

| Gorelik et al. [6]—Pancreatic Cystic Lesions (2024) | Gastroenterology (Pancreatic Cysts) | Customized GPT tested on 60 clinical scenarios | 87% adequate recommendations (52/60 scenarios); comparable to experts | High agreement with gastroenterologists |

| Dehdab et al. [8] Chest CT Interpretation (2024) | Diagnostic classification of chest CT scans | 60 CT scans covering COVID-19, NSCLC, control cases | 56.8% accuracy CNNs (literature: >80–90%) | Suboptimal performance; below clinically acceptable standards |

| Shifai et al. [9] Dermatoscopy (2024) | Dermatology | 50 cases Differentiating melanoma from benign nevi | Poor discrimination: accuracy not clinically adequate CNNs (State-of-the-Art: AUROC > 0.90) | Chat-GPT failed to reach acceptable thresholds; CNNs outperform significantly |

| Feature | Large Language Models (LLMs) | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Text generation, reasoning, multimodal input handling (text + image) | Image classification, segmentation, and feature extraction |

| Strengths | Natural language explanations; integration of text and image; flexible reasoning | High diagnostic accuracy in image tasks; robust for radiology, pathology, dermatology |

| Weaknesses | Suboptimal diagnostic accuracy in image interpretation; hallucinations | Less interpretable; limited to the image domain; not designed for narrative reasoning |

| Clinical Adoption | Early exploratory phase; performance inconsistent | Already integrated into workflows (radiology triage, dermatology lesion detection, pathology slide analysis) |

| Role in Generative AI | Text-to-image analysis and multimodal reasoning | Core architecture for image analysis; benchmark for performance |

| Key Applications of XAI in Surgery | |

|---|---|

| Preoperative planning | Explainable models pinpoint critical variables, driving risk assessments:

|

| Robotic and image-guided surgery | XAI techniques allow surgeons to understand AI-driven anatomical segmentation or instrument planning:

|

| Postoperative monitoring | Transparent alerts help care teams:

|

| Ongoing and Future Directions of XAI | |

|---|---|

| Adaptive and multimodal explanations | Tailored to clinicians’ specialties and contexts. |

| Federated Learning and Privacy-preserving XAI | Enabling trustworthy collaboration across institutions. |

| Human AI co-design | Bringing together surgeons, ethicists, developers, and patients. Ensure tools align with clinical needs and values. |

| XAI Technique | Application in Surgical Context | Strengths and Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| SHAP | Preoperative risk models | Clear feature weights, but computationally heavy |

| LIME | Local explanations of model outputs | Simple instance-level reasoning, but unstable |

| Grad-CAM | Imaging tasks: segmentation, tissue localization | Intuitive visual maps; needs complementing methods |

| Saliency Maps | Fine-grained pixel-level highlighting | Too noisy alone Best when combined with CAM |

| Case-based reasoning | Prototype comparison in decision support | Clinically meaningful, but needs curated databases |

| Overlay XAI in robotics | Real-time anatomy annotation | Intuitive for surgeons, technical integration required |

| Ethical Dimension | Explanation | Implications for Surgical Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Transparency | The degree to which an AI system’s decision-making processes can be understood by humans. | Surgeons must be able to understand how AI systems reach conclusions to ensure safe and reliable use. |

| Accountability | Clear identification of responsibility for AI-driven decisions and outcomes. | Ensures liability is traceable—critical in case of error or adverse events. |

| Fairness and Bias Mitigation | Ensuring AI does not perpetuate or amplify health disparities through biased data or models. | Promotes equity in surgical care across patient demographics and clinical contexts. |

| Autonomy and Informed Consent | Respecting patient autonomy by enabling clinicians to explain AI-supported decisions to patients for shared decision-making. | Enhances trust and ensures ethically valid consent processes. |

| Safety and Reliability | Guaranteeing that AI models perform consistently and robustly, especially in high-risk settings like surgery. | Reduces the risk of harm from erroneous or unstable AI recommendations. |

| Privacy and Data Protection | Ensuring patient data used in training and deploying AI models is handled ethically and complies with regulations (e.g., GDPR). | Maintains trust and adheres to legal standards in AI development and application. |

| Professional Integrity | AI should support—not replace—clinical expertise, preserving the surgeon’s professional judgment and decision-making autonomy. | Encourages human oversight and prevents overreliance on “black-box” tools. XAI is expected to be a technical solution, and at the same time a philosophical safeguard, thereby enhancing, not undermining, surgical autonomy. |

| Education and Literacy | Ethical deployment of AI requires clinicians to be adequately trained in understanding and interpreting AI tools. | Promotes safe integration and helps clinicians challenge AI recommendations when appropriate. |

| Year | Journal | Study/First Author | Surgical Domain | Task | XAI Method(s) | N/Dataset | Study Type | Design (Retro/Prosp) | Centers (Single/Multi) | External Validation | Prospective Data Collection | Human-Factors/Usability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | npj Digital Medicine | Riva-Cambrin et al. [79] | General (robotic and endoscopic video) | Task and skill classification with transparent ‘liquid white box’ | White-box design + interpretable features | Surgical video datasets | Methodology + validation | Method + retrospective | Multi-dataset (video) | No/Unclear | No/Unclear | No |

| 2024 | JCO Clinical Cancer | Hernandez et al. [80] | Oncologic surgery (inpatients with cancer) | Preoperative prediction of postoperative complications | SHAP-based explanations | Single health system inpatients with cancer | Model development and validation | Retrospective EHR | Single health system | No/Unclear | No/Unclear | No |

| 2024 | Surgical Endoscopy (open via PMC) | Lopez-Lopez et al. [81] | Hepatobiliary (laparoscopic liver resection, segments 7–8) | Predict surgical complexity, outcomes, and conversion to open | SHAP (global and local) | 585 pts, 19 hospitals (international) | International multicenter study | Retrospective (international registry) | Multicenter (19 hospitals) | No/Unclear | No | No |

| 2025 | Journal of Thoracic Disease | Wang et al. [82] | Thoracic surgery | Predict postoperative pulmonary complications | Explainable ML (e.g., SHAP algorithm) | Retrospective cohort | Model development and validation | Retrospective cohort | Single-center (per article) | No/Unclear | No | No |

| 2022 | International Journal of Surgery | Fransvea et al. [83] | Emergency general surgery (elderly) | Predict 30-day postoperative mortality | Interpretable ML models (reporting feature effects) | FRAILESEL multicenter registry (Italy) | Prospective cohort secondary analysis | Retrospective | Multicenter (Italy) | No/Unclear | Yes (prospective registry) | No |

| 2022 | JAMA Network Open | Deng et al. [84] | Surgical oncology (cytoreductive surgery) | Predict major postoperative complications | SHAP (feature attribution, dependence plots) | Multicenter CRS cohort | Development and external validation | Retrospective development + external validation | Multicenter | Yes | No | No |

| 2021 | Scientific Reports | Zeng et al. [85] | Pediatric cardiac surgery | Predict postoperative complications using intraop BP + EHR | SHAP (global + patient-level) | 1964 pts (single center, China) | Model development and internal validation | Development/benchmarking | Single-center | No/Unclear | No | No |

| 2023 | Sensors | Arabian et al. [86] | General laparoscopic (video) | Phase recognition with attention module (P-CSEM) | Attention maps/saliency for interpretability | Cholecystectomy datasets | Method + benchmarking | Development/benchmarking | Single-center/Unclear | No/Unclear | No | No |

| 2022 | Surgical Endoscopy (Springer) | Shinozuka et al. [87] | Hepatobiliary (lapcholecystectomy) | Surgical phase recognition from endoscopic video | Post hoc visualization (e.g., saliency/attention) | LC videos | Model development | Method (video) | Single-center/Unclear | No/Unclear | No | No |

| Year | Journal | Study/First Author | Surgical Domain | Human Factors/Usability | Latency | Effect Size | Precision–Recall | Validation Type | Human-Factors Assessment | Intraoperative Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | npj Digital Medicine | Riva-Cambrin et al. [79] | General (robotic and endoscopic video) | No | Not reported (video inference latency seldom reported) | Not reported | Not reported | Internal (multi-dataset) | No HFE evaluation | High (direct intraop video analysis) |

| 2024 | JCO Clinical Cancer | Hernandez et al. [80] | Oncologic surgery (inpatients with cancer) | No | Not reported | Not reported | May include class-specific precision/recall (not PR-AUC) | Internal only | Not evaluated | Low (preoperative only) |

| 2024 | Surgical Endoscopy (open via PMC) | Lopez-Lopez et al. [81] | Hepatobiliary (laparoscopic liver resection, segments 7–8) | No | Not reported | Some ORs for risk (depending on model output) | Precision sometimes reported; PR-AUC not typical | Internal multicenter | Not evaluated | Moderate (planning but not intraop) |

| 2025 | Journal of Thoracic Disease | Wang et al. [82] | Thoracic surgery | No | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Internal only | Not evaluated | Low |

| 2022 | International Journal of Surgery | Fransvea et al. [83] | Emergency general surgery (elderly) | No | Not reported | Not reported | Possibly precision/recall | Internal multicenter | Not evaluated | Low–Moderate (preop decision-making) |

| 2022 | JAMA Network Open | Deng et al. [84] | Surgical oncology (cytoreductive surgery) | No | Not reported | ORs are often reported in CRS literature | May include class precision/recall | Internal + External | Not evaluated | Low |

| 2021 | Scientific Reports | Zeng et al. [85] | Pediatric cardiac surgery | No | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Internal | Not evaluated | Moderate (intraop features used) |

| 2023 | Sensors | Arabian et al. [86] | General laparoscopic (video) | No | Not reported | Not reported | Typically report F1; PR-AUC rarely | Internal | Not evaluated | High |

| 2022 | Surgical Endoscopy (Springer) | Shinozuka et al. [87] | Hepatobiliary (lapcholecystectomy) | No | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Internal | Not evaluated | High |

| Phase | Task Category | Model Types Used | XAI Techniques | Key Metrics Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | Risk prediction, triage, mortality prediction, complication prediction, and surgical complexity scoring | Tabular ML (GBM, RF, XGBoost), Logistic regression, Transformer models for EHR | SHAP (global/local), feature importance, partial dependence, counterfactuals (rare) | AUROC, AUPRC (rare), calibration (Brier), OR/RR, effect size, sensitivity/specificity |

| Intraoperative | Phase recognition, workflow analysis, skill assessment, anomaly detection, video classification | CNNs, 3D-CNNs, LSTM/GRU, Vision Transformers, “liquid white box” architectures | Saliency maps, Grad-CAM, attention maps, embedded transparency, spatial–temporal attribution | Accuracy, F1, mAP, latency (rare), frame-level error, PR-AUC (rare) |

| Postoperative | Complication forecasting, length-of-stay prediction, readmission, deterioration | Tabular ML, EHR transformers, hybrid temporal models | SHAP, global interpretability methods, rule-based surrogates | AUROC, precision/recall, calibration, effect size estimates |

| Cross-Phase/Systems Level | Workflow optimization, robotic assistance, multimodal integration | Multimodal deep learning, graph neural networks (GNNs), video + EHR models | Saliency, SHAP for multimodal, prototype learning, concept-based explanations | Composite metrics; few studies report latency, human factors, or usability |

| LIME | SHAP | Common Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approach | Local surrogate models for individual predictions | Shapley values from cooperative game theory | Both are post hoc explanation methods |

| Key Assumption | Relies on local linearity | Assumes feature independence | Not designed for temporal or streaming data |

| Sensitivity | Highly sensitive to data perturbation, leading to inconsistent explanations | May overlook spatial and temporal correlations in clinical data | Lack of robustness in dynamic surgical environments |

| Explainability Consistency | Varies across similar cases, undermining real-time clinical trust | More stable, but constrained by underlying assumptions | Can produce misleading or incomplete insights for clinicians |

| Streaming Data Support | Not natively supported | Not natively supported | Critical gap in intraoperative settings, like live endoscopy or sensor monitoring |

| Suitability for Surgery | Poor for real-time decision-making due to a lack of consistency | Limited in procedural workflows with complex and evolving inputs | Inadequate for high-frequency surgical data requiring rapid interpretability |

| Regulatory Alignment | Difficult to justify in auditable or legal contexts | Better aligned with auditability, but lacks full clinical interpretability | Neither fully complies with the transparency requirements for high-risk medical decisions |

| Study Type | Frameworks | XAI Artifacts to Archive | Regulatory Hooks (EU AI Act/GDPR/Device Systems) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model development | TRIPOD-AI, DECIDE Stage 0–1 | Saliency maps, feature attribution logs, model cards, training data snapshots | GDPR minimization; AI Act documentation; ISO 14971 risk files |

| Retrospective validation | TRIPOD-AI, DECIDE Stage 2 | Cohort-linked explanations, metadata, pseudonymized IDs | AI Act Art. 12 record-keeping; MDR Annex IV technical docs |

| Prospective feasibility | DECIDE Stage 3, IDEAL 2a/2b | Real-time explanations, clinician feedback, usability logs | IEC 62366 usability; AI Act transparency and audit trail |

| RCTs | SPIRIT-AI, CONSORT-AI, IDEAL 3 | Full model+XAI version bundle; explanation reproducibility | MDR clinical evidence; AI Act transparency and data integrity |

| Post-market monitoring | IDEAL 4, AI Act Art. 61 | Explanation-stream logs, drift detection, concept instability | AI Act post-market surveillance; ISO 14971 ongoing risk |

| Frameworks | |

|---|---|

| TRIPOD-AI (Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis—AI extension) | Provides reporting standards for developing and validating AI prediction models; ensures transparency, reproducibility, and clear disclosure of model performance and limitations. |

| DECIDE-AI (Developmental and Exploratory Clinical Investigation of Decision-support systems driven by AI) | Guides early-stage clinical evaluation of AI tools, focusing on human–AI interaction, workflow integration, and safety before definitive trials. |

| SPIRIT-AI (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials—AI extension) | Sets standards for protocol design of clinical trials involving AI; ensures transparent, pre-registered trial methodology. |

| CONSORT-AI (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials—AI extension) | Provides detailed guidelines for reporting AI-enabled randomized controlled trials, including intervention description and AI model behavior. |

| IDEAL Framework (Idea, Development, Exploration, Assessment, Long-term Study) | Framework for evaluating surgical innovations; applicable to AI to structure translation from prototype to deployment and surveillance. |

| MISE/CLAIM/EPF (Medical Imaging and Signal Evaluation Frameworks) | Standards for evaluating imaging, sensor, and video-based AI models; emphasize dataset description, benchmarking, reproducibility, and methodological rigor. |

| PROBAST-AI (Prediction Model Risk of Bias Assessment Tool—AI Extension) | Tool for assessing risk of bias and applicability in AI prediction-model studies; identifies methodological weaknesses and overfitting. |

| EU AI Act | Regulates high-risk clinical AI systems; mandates documentation, transparency, human oversight, post-market monitoring, and auditable explanation logs. |

| GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) | Governs personal-data handling; establishes requirements for pseudonymisation, data minimisation, storage of explanation artifacts, and privacy protection. |

| ISO 13485 (Medical Device Quality Management Systems) | Defines quality-management and documentation requirements for medical devices, including AI models and their XAI pipelines. |

| ISO 14971 (Risk Management for Medical Devices) | Requires systematic identification, analysis, and mitigation of risks—including risks introduced by misleading or unstable explanations. |

| IEC 62304 (Software Lifecycle Processes) | Specifies lifecycle management, version control, and maintenance requirements for medical device software, including AI models and XAI components. |

| IEC 62366 (Usability Engineering for Medical Devices) | Establishes usability engineering standards; ensures safe, effective clinician interaction with AI systems and interpretability interfaces. |

| MDR (EU Medical Device Regulation) | Regulates clinical evidence generation, technical documentation, and post-market surveillance for AI systems seeking CE marking. |

| Step | Question to Ask | Practical Actions in AI Model Validation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Clarify the causal question | What is the intervention/exposure, and what is the outcome? What is the causal effect we hope the model will support? | Define explicitly in the protocol; e.g., “If we do X (intervention), then Y (outcome) will change by Δ”. Avoid ambiguous phrasing like “predict Y from X” when the goal is to infer “X causes Y”. |

| 2. Specify the causal structure | What variables are on the pathway, what are confounders, mediators, and colliders? Can we map a directed-acyclic graph (DAG) or a potential-outcome model? | Construct a DAG as part of model development; use domain knowledge (clinicians + data team) to list confounders or hidden variables. Use this to guide variable selection, adjustment strategy, and interpretation of model features. |

| 3. Assess data adequacy for causal inference | Does the dataset support the assumptions needed for causal inference? What about: completeness of confounder measurement, absence of unmeasured confounding, timing of exposures/outcomes (temporal order), possibility of reverse causation? |

|

| 4. Choose and apply appropriate causal estimation methods | Is a simple predictive model enough, or do we need causal-specific methods (e.g., propensity score matching/weighting, instrumental variables, inverse probability weighting)? What assumptions underlie each approach? | In AI model validation for clinical use:

|

| 5. Validate model results for transportability and robustness | Do the causal claims hold across populations, sites, and time periods? Does the AI model’s behavior change under shift (population, measurement, intervention)? | Perform external validation (other hospitals, different patient mix). Conduct sensitivity analyses; e.g., how much unobserved confounding would invalidate the conclusion? Report robustness to hidden bias. Check whether causal effect estimates (or model predictions) vary significantly under realistic shifts. |

| 6. Interpret and communicate findings cautiously | Are we inadvertently making causal claims when only associations are supported? Are we clear about the limitations and remaining uncertainties? | In the manuscript: emphasize “This model predicts Y given X; it does not necessarily mean X causes Y unless assumptions hold.” Provide caveats about confounding, bias, and generalisability. Avoid words like “causes” unless the design supports it. Use language such as “may be associated with”, “in this dataset under these assumptions, an effect of X on Y is estimated as …”. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopes, S.; Mascarenhas, M.; Fonseca, J.; Fernandes, M.G.O.; Leite-Moreira, A.F. Unveiling the Algorithm: The Role of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Modern Surgery. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243208

Lopes S, Mascarenhas M, Fonseca J, Fernandes MGO, Leite-Moreira AF. Unveiling the Algorithm: The Role of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Modern Surgery. Healthcare. 2025; 13(24):3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243208

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopes, Sara, Miguel Mascarenhas, João Fonseca, Maria Gabriela O. Fernandes, and Adelino F. Leite-Moreira. 2025. "Unveiling the Algorithm: The Role of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Modern Surgery" Healthcare 13, no. 24: 3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243208

APA StyleLopes, S., Mascarenhas, M., Fonseca, J., Fernandes, M. G. O., & Leite-Moreira, A. F. (2025). Unveiling the Algorithm: The Role of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Modern Surgery. Healthcare, 13(24), 3208. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13243208