The Impact of Sibling Presence on Motor Competence and Physical Fitness: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

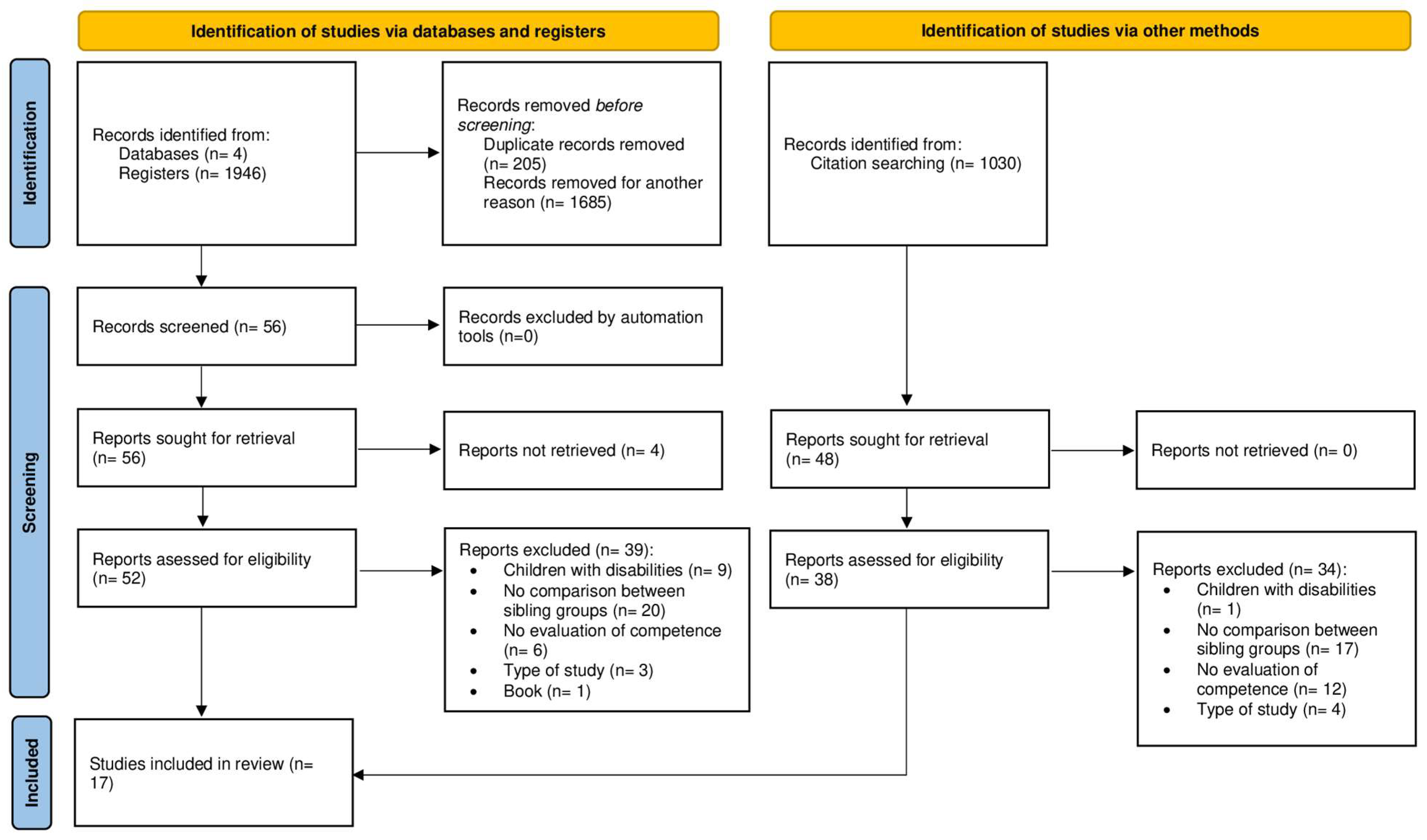

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection Results

3.2. Design and Samples

3.3. Interventions Characteristics

3.4. Main Outcomes

3.4.1. Does Having Older Siblings Affect Motor Competence?

3.4.2. Does Having Older Siblings Affect Physical Fitness?

3.4.3. Does Having Siblings Affect Motor Competence?

3.4.4. Does Having Siblings Affect Physical Fitness?

3.5. Quality Appraisal Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Utesch, T.; Bardid, F.; Büsch, D.; Strauss, B. The Relationship Between Motor Competence and Physical Fitness from Early Childhood to Early Adulthood: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallahue, D.L.; Ozmun, J.C.; Goodway, J. Understanding Motor Development: Infants, Children, Adolescents, Adults, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carson Sackett, S.; Edwards, E.S. Relationships among Motor Skill, Perceived Self-Competence, Fitness, and Physical Activity in Young Adults. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2019, 66, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denche-Zamorano, Á.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Muñoz-Bermejo, L.; Rojo-Ramos, J.; Pastor-Cisneros, R.; Giakoni-Ramírez, F.; Godoy-Cumillaf, A.; Barrios-Fernandez, S. A Cross-Sectional Study on Self-Perceived Health and Physical Activity Level in the Spanish Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevan, I.; Barnett, L.M. Considerations Related to the Definition, Measurement and Analysis of Perceived Motor Competence. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 2665–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, N.; Jacinto, M.; Monteiro, D.; Matos, R.; Sergio, J.I. Effects of a Twelve-Week Sports Program on Motor Competence 2 in Children Aged 6 to 10 Years Old—A Study Protocol. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garciá-Hermoso, A.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Garciá-Alonso, Y.; Alonso-Martínez, A.M.; Izquierdo, M. Association of Cardiorespiratory Fitness Levels during Youth with Health Risk Later in Life: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 952–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspersen, C.; Powell, K.; Christenson, G. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness: Definitions and Distinctions for Health-Related Research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raghuveer, G.; Hartz, J.; Lubans, D.; Wiltz, J.; Mietus-snyder, M.; Perak, A.; Baker-smith, C.; Pietris, N.; Edwards, N. Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Youth—An Important Marker of Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 142, e101–e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, F.B.; Ruiz, J.R.; Castillo, M.J.; Sjöström, M. Physical Fitness in Childhood and Adolescence: A Powerful Marker of Health. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodden, D.; Sacko, R.; Nesbitt, D. A Review of the Promotion of Fitness Measures and Health Outcomes in Youth. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 11, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganley, K.J.; Paterno, M.V.; Miles, C.; Stout, J.; Brawner, L.; Girolami, G.; Warren, M. Health-Related Fitness in Children and Adolescents. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2011, 23, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drenowatz, C.; Greier, K. Resistance Training in Youth—Benefits and Characteristics. J. Biomed. 2018, 3, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.J.; Eather, N.; Morgan, P.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Lubans, D.R. The Health Benefits of Muscular Fitness for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Costoso, A.; López-Muñoz, P.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Cavero-Redondo, I. Association Between Muscular Strength and Bone Health from Children to Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1163–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo-Cantarero, A.; Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Martínez-Vizcaino, V.; Redondo-Tébar, A.; Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; Sánchez-López, M. Relationship between Both Cardiorespiratory and Muscular Fitness and Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Yoon, S.H.; Lee, S.M. Exploring the Relationship between Fundamental Movement Skills and Health-Related Fitness among First and Second Graders in Korea: Implications for Healthy Childhood Development. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hermoso, A.; Izquierdo, M.; Ramírez-Vélez, R. Tracking of Physical Fitness Levels from Childhood and Adolescence to Adulthood: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transl. Pediatr. 2022, 11, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breau, B.; Brandes, M.; Veidebaum, T.; Tornaritis, M.; Moreno, L.A.; Molnár, D.; Lissner, L.; Eiben, G.; Lauria, F.; Kaprio, J.; et al. Longitudinal Association of Childhood Physical Activity and Physical Fitness with Physical Activity in Adolescence: Insights from the IDEFICS/I.Family Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigmundsson, H.; Haga, M. Motor Competence Is Associated with Physical Fitness in Four- to Six-Year-Old Preschool Children. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 24, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattuzzo, M.T.; dos Santos Henrique, R.; Ré, A.H.N.; de Oliveira, I.S.; Melo, B.M.; de Sousa Moura, M.; de Araújo, R.C.; Stodden, D. Motor Competence and Health Related Physical Fitness in Youth: A Systematic Review. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, E.; Horii, D.; Kano, T. Genetic and Environmental Effects on Physical Fitness and Motor Performance. Int. J. Sport Health Sci. 2005, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venetsanou, F.; Kambas, A. Environmental Factors Affecting Preschoolers’ Motor Development. Early Child. Educ. J. 2010, 37, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Luo, J.; Chen, Y. Effects of Kindergarten, Family Environment, and Physical Activity on Children’s Physical Fitness. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 904903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergera, S.E.; Nuzzo, K. Older Siblings Influence Younger Siblings’ Motor Development. Infant. Child. Dev. 2008, 17, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyre, H.; Albaret, J.; Bernard, J.Y.; Hoertel, N.; Melchior, M.; Forhan, A.; Taine, M.; Heude, B.; De Agostini, M.; Galéra, C.; et al. Developmental Trajectories of Motor Skills during the Preschool Period. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 1461–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHale, S.M.; Updegraff, K.A.; Whiteman, S.D. Sibling Relationships and Influences in Childhood and Adolescence. J. Marriage Fam. 2012, 74, 913–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derikx, D.F.A.A.; Kamphorst, E.; van der Veer, G.; Schoemaker, M.M.; Hartman, E.; Houwen, S. The Relationships between Sibling Characteristics and Motor Performance in 3-to 5-Year-Old Typically Developing Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.Y.; Wang, T.T.; Tai, H.L. The Impact of Different Family Background on Children’s Fundamental Movement Skills Proficiency. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva-Bartoll, O.; Estevan, I. Gender, Family Environment and Leisure Physical Activity as Associated Factors with the Motor Coordination in Childhood. A Pilot Study. RICYDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Del. Deport. 2019, 15, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruise, S.; O’Reilly, D. The Influence of Parents, Older Siblings, and Non-Parental Care on Infant Development at Nine Months of Age. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2014, 37, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Devesa, D.; López-Eguía, A.; Amoedo, L.; Ayán-Pérez, C. Associations between Agility, the Relative Age Effect, Siblings, and Digit Ratio (D2:D4) in Children and Adolescents. Children 2024, 11, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Devesa, D.; Diz-Gómez, J.C.; Vicente-Vila, P.; Fernández, M.D.; Rodríguez, M.R.; Carballo-Afonso, R.; Sanchez-Lastra, M.A.; Ayán-Pérez, C. Associations Between Relative Age, Siblings, and Motor Competence in Children and Adolescents. Children 2025, 12, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashida, K.; Nakatsuka, M. Promoting Factors of Physical and Mental Development in Early Infancy: A Comparison of Preterm Delivery/Low Birth Weight Infants and Term Infants. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2014, 19, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Yang, Z.; Xin, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, T. Differences in School Performance Between Only Children and Non-Only Children: Evidence From China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 608704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krombholz, H. Physical Performance in Relation to Age, Sex, Birth Order, Social Class, and Sports Activities of Preschool Children. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2006, 102, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krombholz, H. Motor Development of First Born Compared to Later Born Children in the First Two Years of Life—A Replication. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, V.P.; Monteiro, D. Socio-Cultural and Somatic Factors Associated with Children’s Motor Competence. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2021, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, M.; Serrano, J.; Duarte-Mendes, P.; Paulo, R.; Marinho, D.A. Effect of Siblings and Type of Delivery on the Development of Motor Skills in the First 48 Months of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L.P.; Lima, R.F.; Silva, A.F.; Clemente, F.M.; Camões, M.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Rosemann, T.; Knechtle, B. Physical Fitness and Somatic Characteristics of the Only Child. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.P.; Luz, C.; Cordovil, R.; Mendes, R.; Alexandre, R.; Lopes, V.P. Siblings’ Influence on the Motor Competence of Preschoolers. Children 2021, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáez-Sánchez, M.B.; Gil-Madrona, P.; Martínez-López, M. Psychomotor Development and Its Link with Motivation to Learn and Academic Performance in Early Childhood Education. Rev. Educ. 2021, 392, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šerbetar, I.; Peharda, P.; Plečko, A. Differences in Physical Fitness and Body Measures Between Children with and Without Older Siblings. SKY-Int. J. Phys. Educ. Sport. Sci. 2021, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schild, C.E.; Meigen, C.; Kappelt, J.; Kiess, W.; Poulain, T. Associations between Sociodemographic and Behavioural Parameters and Child Development Depending on Age and Sex: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e065936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareian, E.; Saeedi, F.; Rabbani, V. The Role of Birth Order and Birth Weight in the Balance of Boys Aged 9-11 Years Old. Ann. Appl. Sport Sci. 2014, 2, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Cares-Marambio, K.; Montenegro-Jiménez, Y.; Torres-Castro, R.; Vera-Uribe, R.; Torralba, Y.; Alsina-Restoy, X.; Vasconcello-Castillo, L.; Vilaró, J. Prevalence of Potential Respiratory Symptoms in Survivors of Hospital Admission after Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2021, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, E.; Qin, H.; Zhu, X.; Jin, J. The Influence of Birth Order and Sibling Age Gap on Children’s Sharing Decision. Early Child. Dev. Care 2023, 193, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havron, N.; Ramus, F.; Heude, B.; Forhan, A.; Cristia, A.; Peyre, H. The Effect of Older Siblings on Language Development as a Function of Age Difference and Sex. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 30, 1333–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseeva, O.S.; Kozlova, I.E.; Baskaeva, O.V.; Pyankova, S.D. Intelligence and Sibling Relationship. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 146, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, C.; Vogel, M.; Poulain, T.; Hiemisch, A.; Kiess, W.; Körner, A. Having Siblings Promotes a More Healthy Weight Status-Whereas Only Children Are at Greater Risk for Higher BMI in Later Childhood. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falbo, T.; Lin, S. Sibling Effects on the Development of Obesity. In International Handbook of the Demography of Obesity; Garcia-Alexander, G., Poston, J.D.L., Eds.; International Handbooks of Population; Springer: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, K.; Andronikos, G.; Travlos, A.; Souglis, A.; Fountain, H.; English, C.; Martindale, R.J.J. Relationship between Sibling Characteristics and Talent Development. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2022, 22, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfa-de-la-Morena, J.M.; Pinheiro Paes, P.; Júnior, F.C.; Feitosa, R.C.; Lima de Oliveira, D.P.; Mijarra-Murillo, J.-J.; García-González, M.; Riquelme-Aguado, V. Relationship of Physical Activity Levels and Body Composition with Psychomotor Performance and Strength in Men. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, M.J.; Farrow, D.; MacMahon, C.; Baker, J. Sibling Dynamics and Sport Expertise. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2015, 25, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudsepp, L.; Viira, R. Influence of Parents’ and Siblings’ Physical Activity on Activity Levels of Adolescents. Eur. J. Phys. Educ. 2000, 5, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercê, C.; Branco, M.; Catela, D.; Lopes, F.; Rodrigues, L.P. Cordovil, RLearning to Cycle: Are Physical Activity and Birth Order Related to the Age of Learning How to Ride a Bicycle? Children 2021, 8, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenan, K.; Barclay, K.; Goisis, A. Health Outcomes of Only Children across the Life Course: An Investigation Using Swedish Register Data. Popul. Stud. 2023, 77, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantke, P.M.; Herrmann-Lingen, C.; Rothenberger, A.; Poustka, L.; Meyer, T. Is Only-Child Status Associated with a Higher Blood Pressure in Adolescence? An Observational Study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, N.; Barker, A.R. Endurance Training and Elite Young Athletes. Med. Sport Sci. 2011, 56, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, L.; Hinkley, T.; Okely, A.D.; Salmon, J. Child, Family and Environmental Correlates of Children’s Motor Skill Proficiency. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2013, 16, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honrubia-Montesinos, C.; Gil-Madrona, P.; Losada-Puente, L. Motor Development among Spanish Preschool Children. Children 2021, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathirezaie, Z.; Matos, S.; Khodadadeh, E.; Clemente, F.M.; Badicu, G.; Silva, A.F.; Sani, S.H.Z.; Nahravani, S. The Relationship between Executive Functions and Gross Motor Skills in Rural Children Aged 8–10 Years. Healthcare 2022, 10, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| Web of Science | TI = ((“sibling*” OR “brother*” OR “sister*” OR “twin*”) AND (“psychomotor performance” OR “motor activity” OR “motor competence” OR “motor proficiency” OR “motor ability” OR “motor performance” OR “movement competence” OR “gross motor competence” OR “fundamental movement skills” OR “motor skills” OR “physical fitness”)) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“sibling*” OR “brother*” OR “sister*” OR “twin*”) AND (“psychomotor performance” OR “motor activity” OR “motor competence” OR “motor proficiency” OR “motor ability” OR “motor performance” OR “movement competence” OR “gross motor competence” OR “fundamental movement skills” OR “motor skills” OR “physical fitness”)) |

| SportDiscus | (“sibling*” OR “brother*” OR “sister*” OR “twin*”) AND (“psychomotor performance” OR “motor activity” OR “motor competence” OR “motor proficiency” OR “motor ability” OR “motor performance” OR “movement competence” OR “gross motor competence” OR “fundamental movement skills” OR “motor skills” OR “physical fitness”) |

| MEDLINE/PubMed | (“sibling*”[Title] OR “brother*”[Title] OR “sister*”[Title] OR “twin*”[Title]) AND (“psychomotor performance”[Title] OR “motor activity”[Title] OR “motor competence”[Title] OR “motor proficiency”[Title] OR “motor ability”[Title] OR “motor performance”[Title] OR “movement competence”[Title] OR “gross motor competence”[Title] OR “fundamental movement skills”[Title] OR “motor skills”[Title] OR “physical fitness”[Title]) |

| Fist Author (Year) | Sample | Objective | Measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheng et al. (2025) [30] | Participants (n, sex): 6200 (NR) Age (mean ± SD): 2–6 years With/without siblings (n, sex, age): Children with 1 sibling (n = 2648, NR, NR) Children with 2 siblings (n = 317, NR, NR) Children with 3 siblings (n = 35, NR, NR) Children without sibling (n = 3200, NR, NR) | To explore the impact of different family background on children’s physical activity. | Outcomes: FMS

Measurement tool: Self-reported questionnaire fulfilled by primary caregivers. | Performance on the FMS scale of children in families with siblings was better than that of children in families with only one child.

|

| Chiva-Bartoll & Estevan (2019) [31] | Participants (n, sex): 55 (23F; 22M) Age (mean ± SD): 8.51 ± 0.31 years With/without siblings (n, sex, age): Children with older siblings or siblings of the same age (n = 37, NR, NR) Children without older or same-age siblings (n = 18, NR, NR) | To analyze the relationship between having or not having older siblings and the level of motor coordination. | Outcome: Motor Coordination. Measurement tool: GRAMI-2:

| For the total sample, it was observed that participants with older siblings or siblings of the same age had a higher level of coordination than those without (t = 4.73; p = 0.01). Children with siblings had a higher level of motor coordination than children without siblings (GRAMI-2 total score: 53.97 ± 3.67; vs. 47.91 ± 3.80; p = 0.002). Girls with siblings had a higher level of motor coordination than girls without siblings (GRAMI-2 total score: 49.44 ± 4.33 vs. 41.59 ± 5.55; p = 0.017). |

| Cruise & O’Reilly. (2014) [32] | Participants (n, sex): 10,748 last born infants, NR Age: 9 months With/without siblings (n, sex, age): Children with 1 sibling (n = 3584, NR, NR) Children with 2 or more siblings (n= 2589, NR, NR) Children without sibling (n = 4571, NR, NR) | To examine the influence of parents, siblings, and aspects of non-parental care on infant development. | Outcomes: Gross Motor Function. Fine Motor Function. Measurement tool: Self-reported questionnaire fulfilled by primary caregivers:

| The presence of one or more older siblings in the household increased the risk of failure in gross motor function:

|

| González-Devesa et al. (2024) [33] | Participants (n, sex): 579 (271F; 308M) Age (range; mean ± SD): 7–18; 12.17 ± 2.91 years With/without siblings (n, sex, age): Children with 1 sibling (n = 265, NR, NR) Children with 2 siblings (n = 161, NR, NR) Children with 3 or more sibling (n = 32, NR, NR) Children without sibling (n = 121, NR, NR) | To confirm whether the 2D:4D digit ratio and having siblings are independent factors that affect motor development, as assessed through agility both in children and adolescents. | Outcomes: Agility. Measurement tool: Field-based test: 10 × 5 shuttle run test from EUROFIT battery. | No association was found between 10 × 5 m shuttle run test and number of siblings (Rho = −0.074; p = 0.076). |

| González-Devesa et al. (2025) [34] | Participants (n, sex): 432 (NR) Age (range; mean ± SD): 6–11; 8.81 ± 1.8 years 12–16; 13.52 ± 1.22 years With/without siblings (n, sex, age): Children with older siblings or siblings of the same age (n = 149, NR, NR) Children without older or same-age siblings (n = 283, NR, NR) | To investigate the influence of relative age and the effects of the presence of siblings on the motor competence of children and adolescents. | Outcomes: Motor competence. Measurement tool: CAMSA | The presence of siblings did not have a statistically significant effect on CAMSA performance (p = 0.697; β = −0.019). |

| Hayashida & Nakatsuka (2013) [35] | Participants (n, sex): 318, NR Age: 4 months With/without siblings (n, sex, age): Babies with siblings < 4 years (n = 108, NR, NR) Babies with siblings ≥ 5 years (n = 35, NR, NR) Babies without siblings (n = 141, NR, NR) | To assess correlations between various factors and the physical development of 4-month-old infants. | Outcomes:

Measurement tool: Self-reported questionnaire fulfilled by parents:

| Babies with siblings < 4 years old had lower scores in KIDS-A compared to those without siblings (10.0 [5–14] vs. 11.0 [6–14]; p < 0.001). No differences were found in KIDS-A scores when babies with siblings ≥ 5 years and babies without siblings were compared (11.0 [7–14] vs. 11.0 [6–14]; p > 0.05). Babies with siblings aged ≥5 years had higher scores in KIDS-A compared to babies with siblings < 4 years old (11.0 [7–14] vs. 10.0 [5–14]; p < 0.05). No intergroup differences were found in KIDS-A in any of the groups (none = 10.0 [2–13]; <4 years = 10.0 [4–13]; ≥5 years = 10.0 [6–13]; p = 0.656). |

| Jia et al. (2022) [36] | Participants (n, sex): 91,619 (44320F; 47299M) Age (mean ± SD): 10.4 ± 0.7 With/without siblings (n, sex, age): Children with siblings (n = 62,988, NR, NR) Only children (n = 28,631, NR, NR)

Only children (n = 25,556)

Only children (n = 25,198) | To analyze whether the status of “only child” affects school performance (including physical health). | Outcome: Physical fitness. Measurement tool: Field-based tests:

| Children with siblings achieved significantly better 50 m sprint times compared to only children (p < 0.001). No significant differences in cardiorespiratory fitness were observed between only children and those with siblings (p > 0.05). |

| Krombholz (2006) [37] | Participants (n, sex): 1194 (556F; 638M) Age interval: 43–84 months | To analyze the relationship of three dimensions of physical performance with age, sex, birth order, participation in sport activities, and socioeconomic status and with cognitive performance in preschool children. | Outcomes: Motor Coordination. Measurement tool: Field-based tests:

Outcome: Physical fitness. Measurement tool: Field-based tests:

Outcome: Manual dexterity. Measurement tool: Field-based test:

| Children with older siblings obtained significantly better values than only children in the following:

|

| Krombholz (2023) [38] | Participants (n, sex): 3200 (1568F; 1578M; 54 no gender information) Age interval: 10–14 months With/without siblings (n, sex, age): Children with older siblings (n = 960, NR, NR) Children without older siblings (n = 2240, NR, NR) | To assess the motor development of children without siblings compared to children who had an older sibling in the first two years of life. | Outcome: Motor development. Measurement tool: Self-reported questionnaire fulfilled by parents on the mastering of 18 motor skills:

| Children without older siblings mastered earlier than children with older siblings the following gross motor skills: Bring hands together earlier (72 ± 32 vs. 67 ± 32; p: 0.01). Children without older siblings mastered earlier than children with older siblings the following manual skills:

|

| Lopes & Monteiro (2021) [39] | Participants (n, sex): 181 (84F; 97M) Age ± SD: 6.10 ± 0.47 years | To assess the effect of somatic and selected socio-cultural factors on motor competence of five to six-year-old children. | Outcomes: Motor competence. Measurement tools: Field-based tests: Tennis ball throw for distance. Speed run 15 m. Standing long jump. | No significant association between having or not having siblings and motor competence was observed. |

| Rebelo et al. (2020) [40] | Participants (n, sex): 405 (206F; 199M) Groups of age (n, age ± SD): From 12 to 23 months (n = 107, age = 18.79 ± 3.73) From 24 to 35 months (n = 153, age = 28.07 ± 3.35) From 36 to 48 months (n = 145, age = 39.31 ± 3.56) With/without siblings (n, sex age ± SD): Children with siblings (n = 199, NR, age = 30.61 ± 8.78) Children without siblings (n = 208, NR, age = 30.70 ± 8.67) | To verify whether the presence of siblings influenced the motor skills development of children in the first 48 months of life. | Outcomes: Motor skill development. Measurement tool: PDMS-2: Postural skills, locomotion skills, object manipulation skills, fine manipulation skills, visuo-motor integration skills. Motor quotients (global motricity and fine motricity). | Group of age from 12 to 23 months: Children with siblings showed higher levels than children without siblings in the following:

Children with siblings showed higher levels than children without siblings in the following:

Children with siblings showed higher levels than children without siblings in the following:

|

| Rodrigues et al. (2020) [41] | Participants (n, sex): 540 (270F; 270M) Age interval: 7–15 years With/without siblings (n, sex, age): Children with siblings (n = 399, 202F; 197M, NR) Children without siblings (n = 141, 70F; 71M, NR) Age groups with sibling vs. only child:

| To examine if being an only child is associated with negative differences on somatic growth and physical fitness compared to being a child with siblings. | Outcomes: Physical fitness. Measurement tools: Field-based tests:

| Children with siblings had better values than only child in the following:

|

| Rodrigues et al. (2021) [42] | Participants (n, sex): 161 (74F; 87M) Age interval: 3–6 years With/without siblings (n, sex, age ± SD): Children with siblings (n = 125, 54F; 71M, age = 4.7 ± 0.79) Children without siblings (n = 34, 19F; 15M, age = 4.6 ± 0.70) | To evaluate the effect of siblings on the three dimensions of motor competence (stability, locomotor and manipulative). | Outcomes: Motor competence. Measurement tool: MCA:

| Children with siblings show a higher percentile average for total MCA and all subscales, nevertheless not statistically significant. No statistically significant differences in the MCA total classification were observed, indicating that a higher percentage of children with siblings placed in the higher proficiency group (37% vs. 18%) and a lower percentage in the average proficiency group (30% vs. 50%). The strength of the association was low (Cramer’s V = 0.20). No other statistically significant differences were observed for all other MCA subscales. |

| Sáez-Sánchez et al. (2021) [43] | Participants (n, sex): 215 (101F; 114M) Age interval (mean ± SD): 3–6 years (3.98 ± 0.82) Groups of age: From 3 years to 3 years and 11 moths (n = 70) From 4 years to 4 years and 11 moths (n = 83) > 5 years (n = 62) With/without siblings (n, sex, age):

| To ascertain whether there are relations of dependency between psychomotor performance in early childhood education and the number of siblings. | Outcomes: Pyschomotor Performance. Measurement tool: Checklist of Psychomotor Activities

| Having siblings had a significant impact both on physical (U = 3795.5; p < 0.01; d = 0.53) and perceptual (U = 4085.5; p < 0.01; d = 0.43) motor aspects. |

| Šerbetar et al. (2021) [44] | Participants (n, sex): 108 (67F; 41M) Age interval (mean ± SD): 9–10 years (9.45 ± 0.50) With/without siblings (n, sex, age):

| To determine whether children with an older siblings differ from the children without older siblings in physical fitness and body measures. | Outcomes: Motor fitness. Measurement tool: Presidents Challenge Battery

| Children with older siblings showed higher levels than children without siblings in the following:

|

| Schild et al. (2022) [45] | Participants (n, sex): 778 (378F; 400M) Age (mean ± SD; range): 2.67 ± 1.78 years < 2 years (n = 349) 2–6 years (n = 429) With/without siblings (n, sex, age): With siblings (n = 225, NR, NR) Without siblings (n = 269, NR, NR) | To explore environmental and individual factors that are associated with child development and to investigate whether the strength of these associations differs according to the age of the children. | Outcomes: Body Motor Skills. Hand Motor Skills. Measurement tool: Self-reported questionnaire fulfilled by parents:

| Children with older siblings had better levels than children without siblings in the following:

|

| Zareian et al. (2014) [46] | Participants (n, sex): 94, NR Age interval: 9–11 years | To study the role of birth order and birth weight in the static and dynamic balance of boys aged 9–11 years old. | Outcomes: Motor competence:

Measurement tool: Lincoln Oseretsky Motor Development Scale. | Birth order had a significant influence on static balance (F-stat = 53.231; p = 0.001). Static balance for second children was higher than the first and only children at all levels. |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | Overall Rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheng et al. (2025) [30] | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | NA | + | Fair |

| González-Devesa et al. (2025) [34] | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | NA | + | Fair |

| González-Devesa et al. (2024) [33] | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | NA | - | Fair |

| Krombholz (2023) [38] | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | NA | - | Poor |

| Schild et al. (2022) [45] | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | NA | + | Fair |

| Jia et al. (2022) [36] | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | NA | + | Fair |

| Sáez-Sánchez et al. (2021) [43] | + | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | NA | - | Poor |

| Šerbetar et al. (2021) [44] | + | - | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | NA | - | Poor |

| Rodrigues et al. (2021) [42] | + | - | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | NA | - | Poor |

| Lopes & Monteiro (2021) [39] | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | - | NA | + | Fair |

| Rodrigues et al. (2020) [41] | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | - | NA | - | Fair |

| Rebelo et al. (2020) [40] | + | - | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | NA | - | Poor |

| Chiva-Bartoll & Estevan (2019) [31] | + | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | NA | - | Poor |

| Zareian et al. (2014) [46] | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | NA | - | Fair |

| Hayashida & Nakatsuka (2014) [35] | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | NA | - | Fair |

| Cruise & O’Reilly (2014) [32] | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | NA | - | Fair |

| Krombholz (2006) [37] | + | - | + | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | - | NA | - | Fair |

| % studies meeting the criterion | 100 | 65 | 82 | 88 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 71 | 94 | 18 | 100 | 0 | NA | 29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blanco-Martínez, N.; González-Devesa, D.; Vila, P.V.; Esmerode-Iglesias, A.; Ayán-Pérez, C. The Impact of Sibling Presence on Motor Competence and Physical Fitness: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233142

Blanco-Martínez N, González-Devesa D, Vila PV, Esmerode-Iglesias A, Ayán-Pérez C. The Impact of Sibling Presence on Motor Competence and Physical Fitness: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233142

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlanco-Martínez, Nerea, Daniel González-Devesa, Pedro Vicente Vila, Antía Esmerode-Iglesias, and Carlos Ayán-Pérez. 2025. "The Impact of Sibling Presence on Motor Competence and Physical Fitness: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233142

APA StyleBlanco-Martínez, N., González-Devesa, D., Vila, P. V., Esmerode-Iglesias, A., & Ayán-Pérez, C. (2025). The Impact of Sibling Presence on Motor Competence and Physical Fitness: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(23), 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233142