Invisible Pain, Visible Inequalities: Gender, Social Agency, and the Health of Women with Fibromyalgia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Materials and Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics of the Sample

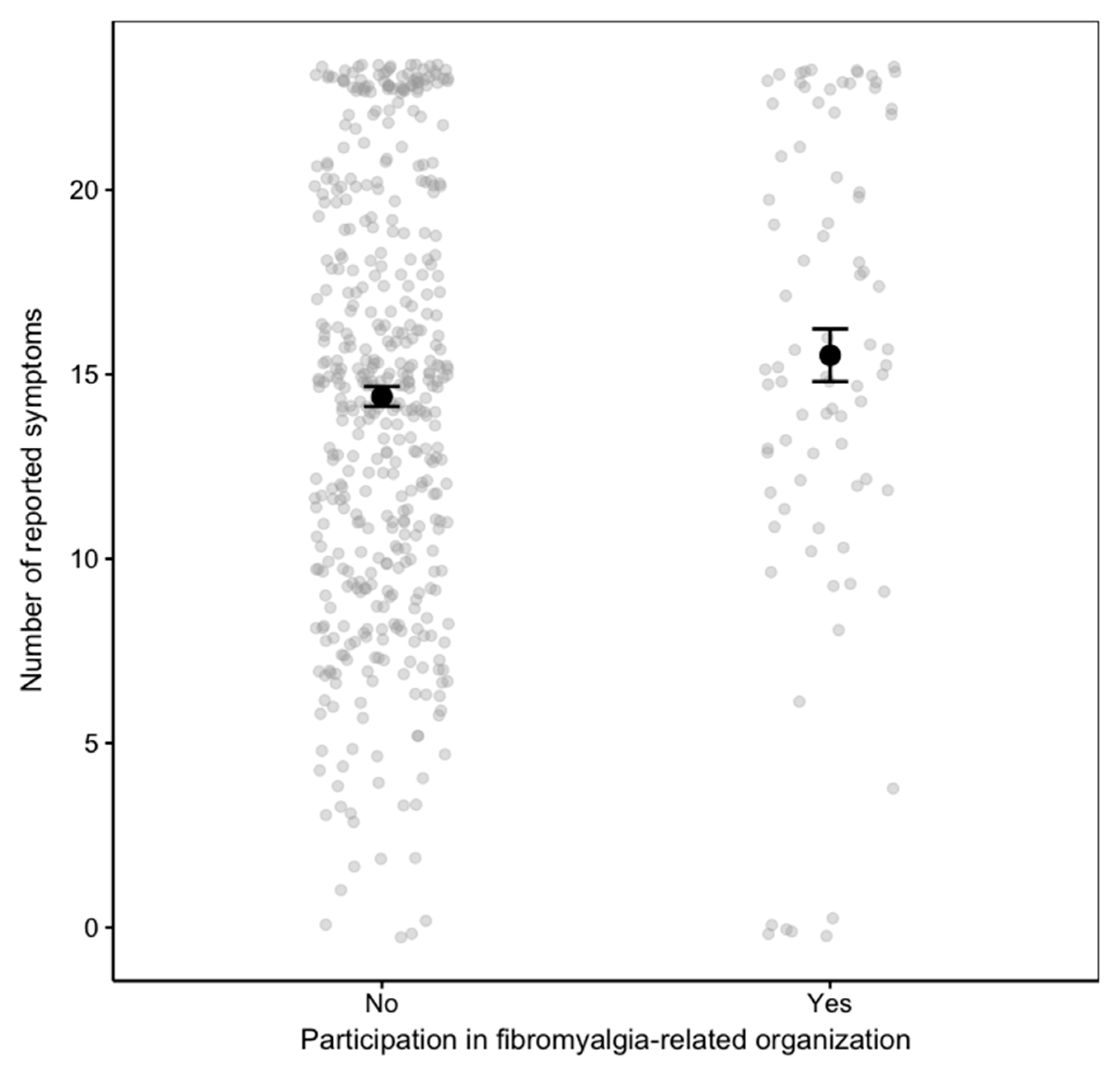

3.2. Predictors of Symptom Count

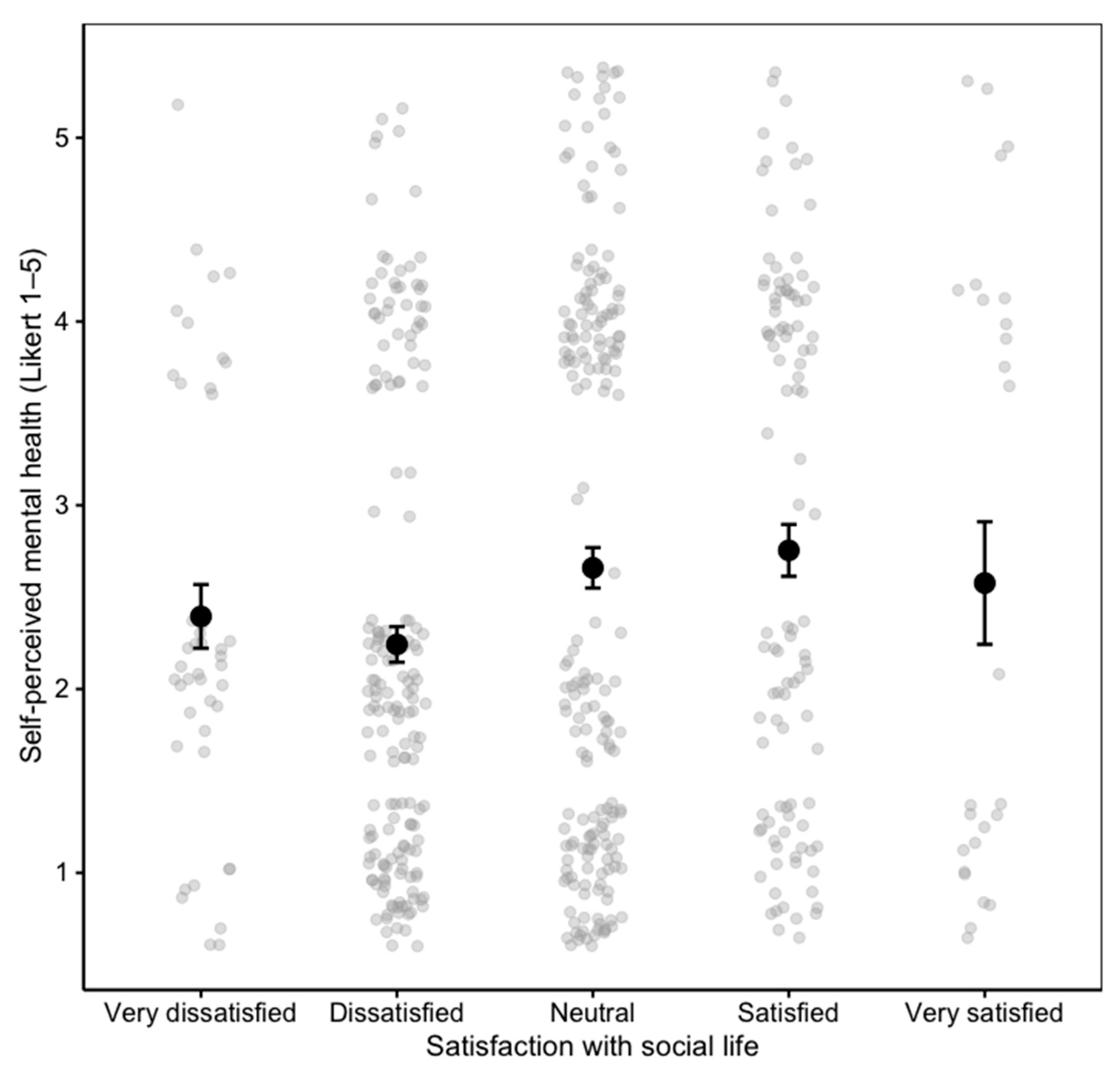

3.3. Predictors of Self-Perceived Mental Health

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FM | Fibromyalgia |

| ICD-11 | International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- icd.who.int. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en#785363034 (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Barbosa-Torres, C.; Cubo-Delgado, S. Eficacia del protocolo SMR en mujeres con fibromialgia para la mejora del dolor crónico, el sueño y la calidad de vida. Psicol. Conductual 2021, 29, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar Kayla, A.; Crum, L.; LaChapelle Diane, L. Lived Experiences of Cognitive Dysfunction in Fibromyalgia: How Patients Discuss Their Experiences and Suggestions for Patient Education. J. Patient Exp. 2024, 11, 23743735241229385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw Daniel, J.; Fitzcharles Mary-Ann, G.; Don, L.; Katz, R.S.; Mease, P.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Winfield, J.B.; Yunus, M.B. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, F.; Afshari, M.; Moosazadeh, M. Prevalence of fibromyalgia in general population and patients, a systematic re-view and meta-analysis. Rheumatol. Int. 2017, 37, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.P.; de Sousa do Espírito Santo, A.; Berssaneti, A.A.; Matsutani, L.A.; Lee, K.Y.S. Prevalência de fibromialgia: Atualização da revisão de literatura. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2017, 4, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Ruiz-Tagle, J.I. Fibromialgia, sus manifestaciones, historia y prevalencia. In Fibromialgia, Más Allá del Cuerpo; Lizama-Lefno, A., Vargas Ruiz-Tagle, J., Rojas Contreras, G., Eds.; USACH: Santiago, Chile, 2021; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, F.; Walitt, B.; Perrot, S.; Rasker Johannes, J.; Häuser, W. Fibromyalgia diagnosis and biased assessment: Sex, prevalence and bias. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuyul, I.; Contreras, M.; Ordoñez, R.; Neira, P.; Maragaño, N.; Rodríguez, A. Recomendaciones clínicas para la rehabilitación de personas con fibromialgia. Una revisión narrativa. Rev. Soc. Esp. Dolor 2021, 28, 194–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kumbhare, D.; Ahmed, S.; Watter, S. A narrative review on the difficulties associated with fibromyalgia diagnosis. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2018, 10, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, I. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis and treatment of fibromyalgia. Rheumatol. Int. 2019, 39, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupit, C.; Finlay, T.; Pope, C. Mapping the Social Organisation of Neglect in the Case of Fibromyalgia: Using Smith’s Sociology for People to Inform a Systems-Focused Literature Review. Sociol. Health Illn. 2025, 47, e70008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavidel-Parsa, B.; Bidari, A.; Tohidi, S.; Shenavar, I.; Kazemnezhad, L.E.; Hosseini, K.; Khosousi, M. Implication of invalidation concept in fibromyalgia diagnosis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 2369–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilam, G.; Silvert, J.; Raev, S.; Malka, D.; Gluzman, I.; Rush, M.; Elkana, O.; Aloush, V. Perceived Injustice and Anger in Fibromyalgia with and Without Comorbid Mental Health Conditions: A Hebrew Validation of the Injustice Experience Questionnaire. Clin. J. Pain. 2024, 40, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kool, M.B.; Geenen, R. Loneliness in Patients with Rheumatic Diseases: The Significance of Invalidation and Lack of Social Support. J. Psychol. 2012, 146, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldarwesh, A. Journey of Hope for Patients with Fibromyalgia: From Diagnosis to Self-Management A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloush, V.; Niv, D.; Ablin, N.; Yaish, I.; Elkayam, O.; Elkana, O. Good pain, bad pain: Illness perception and physician attitudes towards rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia patients. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2021, 39, S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengshoel Anne, M.; Sim, J.; Ahlsen, B.; Madden, S. Diagnostic experience of patients with fibromyalgia—A meta-ethnography. Chronic Illn. 2018, 14, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droppert, K.M.; Knowles, S.R. The role of pain acceptance, pain catastrophizing, and coping strategies: A validation of the common sense model in females living with fibromyalgia. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2023, 30, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Martínez, A.R.; Grande-Gascón, M.L.; Calero-García María, J. Influence of socio-affective factors on quality of life in women diagnosed with fibromyalgia. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1229076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, E.; Pujal, I.; Llombart, M.; Albertín, P. Los contextos de vulnerabilidad de género del dolor cronificado. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2017, 75, e058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, J.E.; Delgado, L.M.; Diosa, S.M.; Mendoza, L.J.; Zuleta, V.V. Personalidad, bienestar psicológico y calidad de vida asociada con la salud en mujeres colombianas con fibromialgia. Psicol. Salud 2022, 32, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graminha, V.; Pinto, M.; Oliveira, A.M.; de Carvalho, E.V. Relações entre sintomas depressivos, dor e impacto da fibromialgia na qualidade de vida em mulheres. Rev. Fam. Ciclos Vida Saúde Contexto Soc. 2020, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carro, T.; Vila, A.; Santos-del-Riego, S. Factores biopsicosociales y calidad de vida en fibromialgia desde la terapia ocupacional. Un estudio cualitativo. Cad. Bras. Ter. Ocup. 2023, 31, e3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deggerone, I.; Rodrigues, L.; Rech, P.; Silveira, V.; Colonetti, T.; Bisognin, L.; Rosa, I.; Grande Antonio, J. Fibromyalgia and sexual dysfunction in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 303, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, L.; Calero, J.; Ortega-Martínez, A.R. Impacto social y familiar de la fibromialgia. Semin. Med. 2021, 63, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, M.; Crofford, J.; Mease, J.; Burgess, M.; Palmer, S.C.; Abetz, L.; Martin, S.A. Patient perspectives on the impact of fibromyalgia. Patient Educ. Couns. 2008, 73, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Vozmediano, E. The social construction of fibromyalgia as a health problem from the perspective of policies, professionals, and patients. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, 1275191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-García, J.A.; Rivera-Rivera, L.; Astudillo-García, C.I.; Castillo-Castillo, L.E.; Morales-Chainé, S.; Tejadilla-Orozco, D.I. Determinantes sociales asociados con ideación suicida durante la pandemia por COVID-19 en México. Salud Publica Mex. 2023, 65, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heather, M.; Cronan, A.; Oliver, K. Social support in women with fibromyalgia: Is quality more important than quantity. J. Community Psychol. 2024, 4, 425–438. [Google Scholar]

- Reig-Garcia, G.; Bosch-Farré, C.; Suñer-Soler, R.; Juvinyà-Canal, D.; Pla-Vila, N.; Noell-Boix, R.; Boix-Roqueta, E.; Mantas-Jiménez, S. The Impact of a Peer Social Support Network from the Perspective of Women with Fibromyalgia: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alboom, M.; Baert, F.; Bernardes, S.F.; Bracke, P.; Goubert, L. Coping with a Dead End by Relying on Your Own Compass: A Qualitative Study on Illness and Treatment Models in the Context of Fibromyalgia. Qual. Health Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, C.; Gaffiero, D. Exploring the lived experiences of patients with fibromyalgia in the United Kingdom: A study of patient-general practitioner communication. Psychol. Health 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vall-Roqué, H.; Nieto, R.; Serrat, M.; Sora, B.; Tolo, P.; Ureña, P.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Luciano, J.V.; Pardo, R. Women living with fibromyalgia during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Health Care Women Int. 2025, 46, 628–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, N. The Social Course of Fibromyalgia: Resisting Processes of Marginalisation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizama-Lefno, A.; Mojica, K.; Roco-Videla, Á.; Ruiz-Tagle, J.I.V.; González-Droguett, N.; Muñoz-Yánez, M.J.; Atenas-Núñez, E.; Maureira-Carsalade, N.; Flores Carrasco, S. Association between Drug Use and Perception of Mental Health in Women Diagnosed with Fibromyalgia: An Observational Study. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association (WMA). Declaration of Helsinki-Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chile. (2012, 2 de Abril). “Ley 21.584: Consagra el Derecho a Protección de los Datos Personales” (Última Versión: 28 de Mayo de 2024). Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1039348 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Chile. (2018, 5 de Junio). “Ley 21.096: Consagra el Derecho a Protección de los Datos Personales” (Última Versión: 16 de Junio de 2018). Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1119730&tipoVersion=0 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Amigot, P.; Pujal, M. Desmedicalización de la experiencia de dolor en mujeres: Usos de plataformas virtuales y procesos de agenciamiento subjetivo. Univ. Psychol. 2016, 14, 1551–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, L.; LaChapelle, D. My Fibro Family! A qualitative analysis of facebook fibromyalgia support groups’ discussion content. Can. J. Pain 2022, 6, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengshoel, A.M.; Sallinen, M.; Sim, J.; Ahlsen, B. Exercising an individualized process of agency in restoring a self and repairing a daily life disrupted by fibromyalgia: A narrative analysis. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2025, 7, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-López, A.; Rivera-Rivera, L.; Márquez-Caraveo, M.E.; Toledano-Toledano, F.; Saldaña-Medina, C.; Chavarría-Guzmán, K.; Delgado-Gallegos, J.L.; Katz-Guss, G.; Lazcano-Ponce, E. Estudio de la calidad de vida en cuidadores familiares de personas con discapacidad intelectual. Salud Publica Mex. 2022, 64, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujal, M.; Albertín, P.; Mora, E. Discursos científicos sobre el dolor cronificado sin-causa-orgánica Incorporando una mirada de género para resignificar-repolitizar el dolor. Polít. Soc. 2015, 52, 921–948. [Google Scholar]

- Åsbring, P.; Närvänen, A.L. Women’s Experiences of Stigma in Relation to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, B.; Zanella, E.; Galazzi, A.; Arcadi, P. The Experience of Stigma in People Affected by Fibromyalgia: A Meta-synthesis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 6317–6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alboom, M.; De Ruddere, L.; Kindt, S.L.; Van Ryckeghem, D.; Bracke, P.; Mittinty, M.M.; Goubert, L. Well-being and Perceived Stigma in Individuals With Rheumatoid Arthritis and Fibromyalgia: A Daily Diary Study. Clin. J. Pain. 2021, 37, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, J.; Madden, S. Illness experience in fibromyalgia syndrome: A metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Correa, C.; Acuña-Jujihara, B. Cuerpos que duelen: El género como dispositivo de poder. In Fibromialgia, Más Allá del Cuerpo: Una Aproximación Interdisciplinaria; Lizama-Lefno, A., Vargas Ruiz-Tagle, J., Rojas Contreras, G., Eds.; Editorial USACH: Santiago, Chile, 2021; pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, L.; Bacharach, S.; Nightingale, S.; Filoche, S. Under the umbrella of epistemic injustice communication and epistemic injustice in clinical encounters: A critical scoping review. Ethics Med. Public Health 2025, 33, 101039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Vozmediano, E.; Vives-Cases, C.; Goicolea, I. I’m not the woman I was: Women’s perceptions of the effects of fibromyalgia on private life. Health Care Women Int. 2016, 37, 836–854. [Google Scholar]

- de Myotanh Vázquez Canales, L.; Pereiró Berenguer, I.; Aguilar García-Iturrospe, E.; Rodríguez, C. Dealing with fibromyalgia in the family context: A qualitative description study. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2024, 42, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, V.; Chiu, Y.; Tang, X.; Eagle, D.; Peebles, M.C.; Kanako, I.; Brooks, J.; Chan, F. Association of Employment and Health and Well-Being in People with Fibromyalgia. J. Rehabil. 2017, 3, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lacasse, A.; Bourgault, P.; Choinière, M. Fibromyalgia-related costs and loss of productivity: A substantial societal burden. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia. Presentación de Resultados Casen 2022. 2023. Available online: https://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/encuesta-casen-2022 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Paz, J. Feminización de la pobreza en América Latina. Notas Población 2022, 49, 11–37. [Google Scholar]

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variables | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Symptoms | Social Dimension (M1) | (P51) Participation in a fibromyalgia-related organization |

| (P52) Perception of social recognition | ||

| (P53) Perception of discriminatory treatment | ||

| (P54) Satisfaction with social life | ||

| Family Dimension (M2) | (P36) Family awareness of the disease | |

| (P37) Satisfaction with family economic situation | ||

| (P38) Perception of family support | ||

| (P39) Satisfaction with partnership status | ||

| Social Dimension and Family Dimension (M3) | (P51) Participation in a fibromyalgia-related organization | |

| (P52) Perception of recognition | ||

| (P53) Perception of discriminatory treatment | ||

| (P54) Satisfaction with social life | ||

| (P36) Family awareness of the disease | ||

| (P37) Satisfaction with family economic situation | ||

| (P38) Perception of family support | ||

| (P39) Satisfaction with partnership status | ||

| Self-Perception of Mental Health | Social Dimension (M4) | (P51) Participation in a fibromyalgia-related organization |

| (P52) Perception of social recognition | ||

| (P53) Perception of discriminatory treatment | ||

| (P54) Satisfaction with social life | ||

| Family Dimension (M5) | (P36) Family awareness of the disease | |

| (P37) Satisfaction with family economic situation | ||

| (P38) Perception of family support | ||

| (P39) Satisfaction with partnership status | ||

| Social Dimension and Family Dimension (M6) | (P51) Participation in a fibromyalgia-related organization | |

| (P52) Perception of recognition | ||

| (P53) Perception of discriminatory treatment | ||

| (P54) Satisfaction with social life | ||

| (P36) Family awareness of the disease | ||

| (P37) Satisfaction with family economic situation | ||

| (P38) Perception of family support | ||

| (P39) Satisfaction with partnership status | ||

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) = 43.8 (10.9) | 539 | - |

| Region of residence | Metropolitan Region | 400 | 74.2 |

| Other regions of Chile | 139 | 25.8 | |

| Nationality (P6) | Chilean | 534 | 99.1 |

| Other | 5 | 0.9 | |

| Marital status (P7) | Single (no partner) | 59 | 10.9 |

| Single (with partner) | 115 | 21.3 | |

| Married (no partner) | 40 | 7.4 | |

| Married (with partner) | 221 | 41.0 | |

| Divorced (no partner) | 49 | 9.1 | |

| Divorced (with partner) | 44 | 8.2 | |

| Widowed (no partner) | 9 | 1.7 | |

| Widowed (with partner) | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Has children | Yes | 407 | 78.6 |

| No | 107 | 20.0 | |

| Children under 18 years | Yes | 237 | 44.0 |

| No | 287 | 53.2 | |

| Socioeconomic Group Scale (GSE) * | Level 1 (lowest) | 108 | 21.0 |

| Level 2 | 157 | 30.0 | |

| Level 3 | 133 | 25.0 | |

| Level 4 | 99 | 18.0 | |

| Level 5 (highest) | 8 | 1.5 | |

| Time since diagnosis (P1.1) | <1 year | 78 | 14.5 |

| 1–3 years | 179 | 33.2 | |

| 3–5 years | 111 | 20.6 | |

| 5–10 years | 92 | 17.1 | |

| >10 years | 77 | 14.3 |

| Domain | Code | Question | Scale Type | Range | n | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | QSintomas | Number of reported fibromyalgia symptoms | Count | 0–40 | 539 | 14.6 | 5.88 |

| Dependent Variable | P34 | How would you rate your current mental health? | 5-point Likert | 1–5 | 539 | 2.52 | 1.42 |

| Social Dimension | P51 | Do you participate in a fibromyalgia-related group or organization? | Dichotomous | 0–1 | 535 | 0.155 | 0.362 |

| Social Dimension | P52 | Do you feel socially recognized as a person with fibromyalgia? | 5-point Likert | 1–5 | 536 | 2.93 | 1.18 |

| Social Dimension | P53 | Have you felt discriminated against because of fibromyalgia? | 5-point Likert | 1–5 | 538 | 1.73 | 0.45 |

| Social Dimension | P54 | Overall, how satisfied are you with your social life? | 5-point Likert | 1–5 | 539 | 2.81 | 1.00 |

| Family Dimension | P36 | Is your family aware of your diagnosis? | Nominal (1–3) | 1–3 | 536 | 2.27 | 0.88 |

| Family Dimension | P37 | How satisfied are you with your family’s economic situation? | 5-point Likert | 1–5 | 537 | 3.14 | 0.98 |

| Family Dimension | P38 | How supported do you feel by your family? | 5-point Likert | 1–5 | 538 | 2.73 | 1.19 |

| Family Dimension | P39 | How satisfied are you with your partnership or marital status? | 5-point Likert | 1–5 | 529 | 2.37 | 1.18 |

| Source | Sum of Squares Type III | df | Mean Square | F | p | Partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 5856.049 a | 136 | 43.059 | 1.366 | 0.011 * | 0.317 |

| Intercept | 25,476.134 | 1 | 25,476.134 | 808.475 | 0.001 * | 0.668 |

| P51 | 293.293 | 1 | 293.293 | 9.308 | 0.002 * | 0.023 |

| Error | 12,636.042 | 401 | 31.511 | |||

| Total | 132,653.000 | 538 | ||||

| Corrected Total | 18,492.091 | 537 |

| Source | Sum of Squares Type III | df | Mean Square | F | p | Partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 190.650 a | 282 | 0.676 | 1.515 | 0.001 * | 0.633 |

| Intercept | 402.626 | 1 | 402.626 | 902.476 | 0.001 * | 0.784 |

| P54 | 8.138 | 4 | 2.034 | 4.560 | 0.001 * | 0.069 |

| P37 × P54 | 11.624 | 15 | 0.775 | 1.737 | 0.045 * | 0.095 |

| Error | 110.642 | 248 | 0.446 | NA | ||

| Total | 2706.000 | 531 | NA | |||

| Corrected Total | 301.292 | 530 | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lizama-Lefno, A.; Roco-Videla, Á.; Atenas-Núñez, E.; González-Droguett, N.; Muñoz-Yánez, M.J.; Flores-Carrasco, S.V. Invisible Pain, Visible Inequalities: Gender, Social Agency, and the Health of Women with Fibromyalgia. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3143. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233143

Lizama-Lefno A, Roco-Videla Á, Atenas-Núñez E, González-Droguett N, Muñoz-Yánez MJ, Flores-Carrasco SV. Invisible Pain, Visible Inequalities: Gender, Social Agency, and the Health of Women with Fibromyalgia. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3143. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233143

Chicago/Turabian StyleLizama-Lefno, Andrea, Ángel Roco-Videla, Erick Atenas-Núñez, Nelia González-Droguett, María Jesús Muñoz-Yánez, and Sergio V. Flores-Carrasco. 2025. "Invisible Pain, Visible Inequalities: Gender, Social Agency, and the Health of Women with Fibromyalgia" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3143. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233143

APA StyleLizama-Lefno, A., Roco-Videla, Á., Atenas-Núñez, E., González-Droguett, N., Muñoz-Yánez, M. J., & Flores-Carrasco, S. V. (2025). Invisible Pain, Visible Inequalities: Gender, Social Agency, and the Health of Women with Fibromyalgia. Healthcare, 13(23), 3143. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233143