Exploring Adults’ Experiences with Tirzepatide for Weight Loss: A Mixed-Methods Study

Highlights

- Among 120 adults (mean age 42 ± 13 years; 50.8% male), 91.7% reported weight loss after initiating tirzepatide.

- Average Weight Efficacy Lifestyle (WEL) total score was 91 ± 34 (0–180 scale); higher WEL was observed in females, employed participants, those with coverage, and early in treatment.

- Interviews (n = 15) described high satisfaction with weight loss, better sleep/energy/mood, and mostly mild/transient gastrointestinal effects.

- Findings support pairing pharmacotherapy with behavioral support and addressing affordability/coverage to sustain benefits.

- Findings support the integration of behavioral support alongside tirzepatide pharmacotherapy and highlight the importance of treatment affordability and coverage. Prospective longitudinal studies are warranted to assess the durability of self-efficacy and health outcomes and to test strategies that optimize adherence and equitable access.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Sample Size and Sampling

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Measures (Instruments)

2.7. Data Collection Procedures

2.8. Quantitative Analysis

2.9. Qualitative Analysis

2.10. Mixed-Methods Integration

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Weight Efficacy Lifestyle (WEL) Items

3.3. Associations Between WEL Total and Participant Characteristics

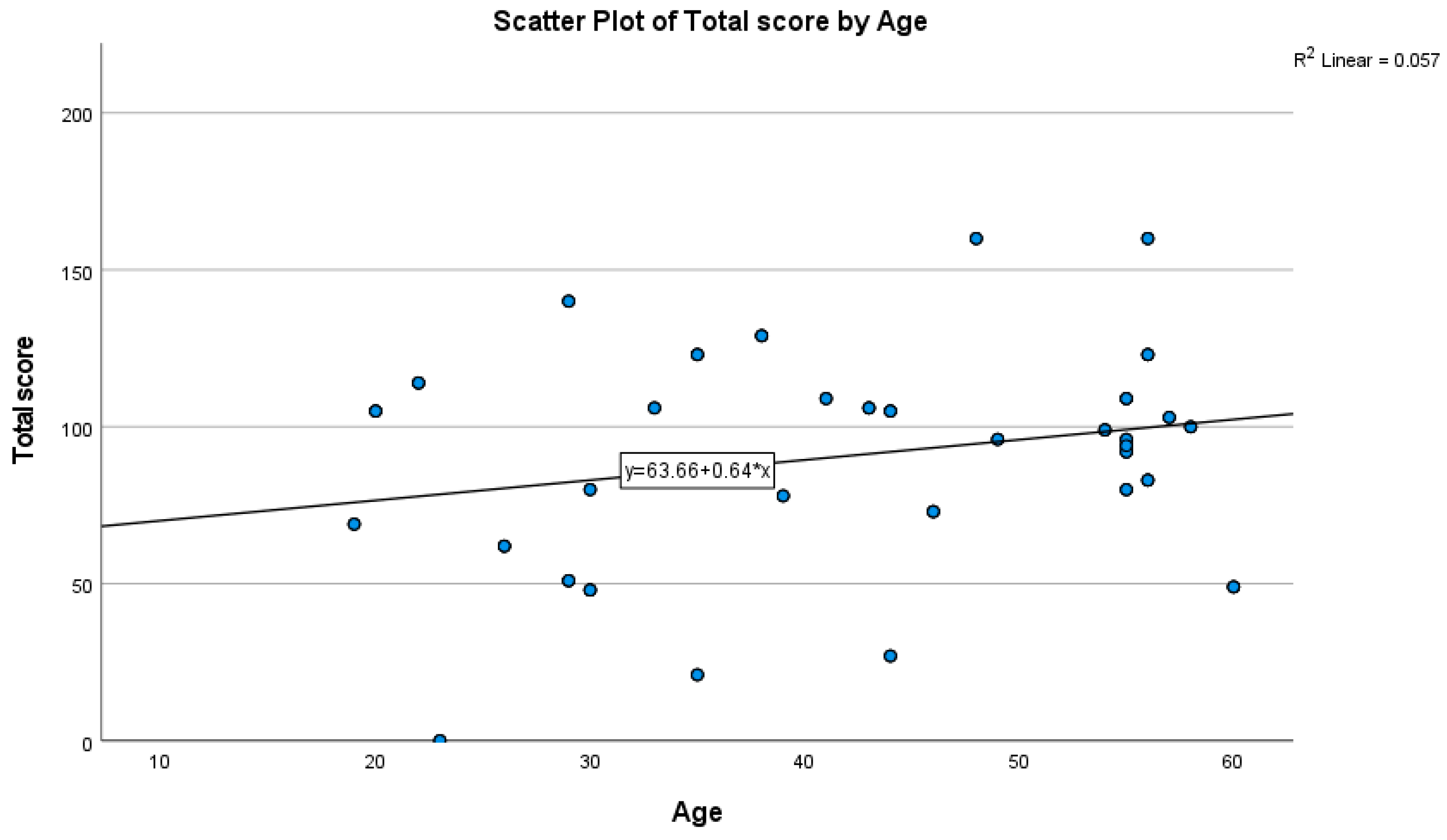

3.4. Correlations of WEL with Age and BMI

3.5. Four Cross-Cutting Themes Emerged (with Typical Variation)

3.6. Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

4. Discussion

Principal Findings in Context

- Pair tirzepatide with structured behavioral support targeting hedonic cues (parties, cravings, high-calorie availability) and negative affect (stress, loneliness).

- Plan adherence supports at the 1–6-month mark (digital check-ins, skills refreshers, dose-escalation side effect troubleshooting).

- Address affordability and coverage barriers to mitigate financial stress that may undermine persistence.

- Track patient-reported outcomes (sleep, mood, energy, social functioning) alongside weight and metabolic markers.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Future Research

5.2. Data Sharing

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight: Fact Sheet. 1 March 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Chavda, V.P.; Ajabiya, J.; Teli, D.; Bojarska, J.; Apostolopoulos, V. Tirzepatide: A New Era of Dual-Targeted Treatment for Diabetes and Obesity—A Mini-Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadden, T.A.; Chao, A.M.; Machineni, S.; Kushner, R.; Ard, J.; Srivastava, G.; Halpern, B.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Bunck, M.C.; et al. Tirzepatide After Intensive Lifestyle Intervention in Adults with Overweight or Obesity: The SURMOUNT-3 Phase 3 Trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2909–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, D.M.; Riddle, M.C.; Cefalu, W.T.; Rosenstock, J.; Bunck, M.C.; Frias, J.P. Effect of Tirzepatide vs. Semaglutide Once Weekly on Glycemic Control and Body Weight in Type 2 Diabetes (SURPASS-2). N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzam, K.; Patel, P. Tirzepatide. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585056/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Approves Mounjaro (Tirzepatide) Injection for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. 13 May 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/drug-trials-snapshots-mounjaro (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. FDA Approves New Medication for Chronic Weight Management. 8 November 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-medication-chronic-weight-management (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Aronne, L.J.; Ahmad, N.N.; Wharton, S.; Connery, L.; Alves, B.; Kiyosue, A.; Zhang, S.; Liu, B.; Bunck, M.C.; et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronne, L.J.; Horn, D.B.; le Roux, C.W.; Ho, W.; Falcon, B.L.; Gomez Valderas, E.; Das, S.; Lee, C.J.; Glass, L.C.; Senyucel, C.; et al. Tirzepatide as Compared with Semaglutide for Weight Reduction in Adults with Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.M.; Abrams, D.B.; Niaura, R.S.; Eaton, C.A.; Rossi, J.S. Self-Efficacy in Weight Management. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.J. Incretin Hormones: Their Role in Health and Disease. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2022, 24 (Suppl. S2), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arillotta, D.; Floresta, G.; Papanti Pelletier, G.D.; Guirguis, A.; Corkery, J.M.; Martinotti, G.; Schifano, F. Exploring the Potential Impact of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists on Substance Use, Compulsive Behavior, and Libido: A Mixed-Methods Study. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierret, A.C.; Benton, M.; Sen Gupta, P.; Ismail, K. A qualitative study of the mental health outcomes in people being treated for obesity and type 2 diabetes with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. Acta Diabetol. 2025, 62, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakoschke, N.; Henry, B.A.; Cowley, M.A.; Lee, K. Tackling Cravings in Medical Weight Management: An Integrated Approach. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Ruiten, C.C.; ten Kulve, J.S.; van Bloemendaal, L.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Veltman, D.J.; IJzerman, R.G. Eating behavior modulates the sensitivity to the central effects of GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment: A secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2022, 137, 105667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmi, V.; Dalle Grave, R.; Leonetti, F.; Solini, A. Female Obesity: Clinical and Psychological Assessment. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1349794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, H.; Huang, D.; Liu, V.; Ammouri, M.A.; Jacobs, C.; El-Osta, A. Digital Engagement and Weight Loss in GLP-1 Therapy Users. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e69466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, L.T.B.; Johnson, V.R. Epidemiology and Significance of Obesity. In The Handbook of Health Behavior Change; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rodbard, H.W.; Barnard-Kelly, K.; Pfeiffer, A.F.; Mauersberger, C.; Schnell, O.; Giorgino, F. Practical Strategies to Manage Obesity in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 2029–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takyi, A.K.; Gaffey, R.H.; Shukla, A.P. Optimizing the Efficacy of Anti-Obesity Medications: A Practical Guide to Personalizing Incretin-Based Therapies. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 2025, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyad, M.A. Embracing the Pros and Cons of the New Weight Loss Medications (Semaglutide, Tirzepatide, Etc.). Curr. Urol. Rep. 2023, 24, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadden, T.A.; Tronieri, J.S.; Butryn, M.L. Lifestyle Modification Approaches for Adult Obesity. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragonieri, S.; Portacci, A.; Quaranta, V.N.; Carratù, P.; Lazar, Z.; Carpagnano, G.E.; Bikov, A. Therapeutic Potential of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome Management: A Narrative Review. Diseases 2024, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter Gibble, T.; Cao, D.; Zhang, X.M.; Xavier, N.A.; Poon, J.L.; Fitch, A. Tirzepatide Improved Quality of Life in SURMOUNT-2. Diabetes Ther. 2025, 16, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalle Grave, R. The Benefit of Healthy Lifestyle in the Era of New Medications to Treat Obesity. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2024, 17, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudzune, K.A.; Stefanski, A.; Cao, D.; Mojdami, D.; Wang, F.; Ahmad, N.; Ling Poon, J. Weight Reduction with Tirzepatide and Quality of Life. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Response | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 61 (50.8) |

| Female | 59 (49.2) | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 42 ± 13 | |

| Employment status | Yes | 77 (64.2) |

| No | 43 (35.8) | |

| Health insurance | No insurance | 42 (35.0) |

| Government insurance | 34 (28.3) | |

| Private insurance | 23 (19.2) | |

| Employer-provided | 21 (17.5) | |

| Payment method for tirzepatide | Personal income | 40 (33.3) |

| Covered by insurance | 35 (29.2) | |

| Partially covered by insurance | 45 (37.5) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | — | 25.74 ± 3.96 |

| Duration of tirzepatide use | <1 month | 27 (22.5) |

| 1–3 months | 31 (25.8) | |

| 3–6 months | 45 (37.5) | |

| >6 months | 17 (14.2) | |

| Previous weight-loss methods tried | No | 104 (86.7) |

| Diet only | 8 (6.7) | |

| Fasting | 4 (3.3) | |

| Physical activities | 4 (3.3) | |

| Weight loss since starting tirzepatide | None | 10 (8.3) |

| <5% of initial weight | 45 (37.5) | |

| 5–10% | 32 (26.7) | |

| >10% | 33 (27.5) | |

| Item | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| I can resist eating when I feel anxious (stressed). | 4 ± 3 |

| I can resist eating even when I have to say “No” to others. | 5 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating even when others pressure me to eat. | 5 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating when I feel tired. | 5 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating even when high-calorie foods are available. | 4 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating when I am angry. | 5 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating when I feel depressed. | 4 ± 2 |

| I cannot resist eating when I am at a party. | 4 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating even when I am happy and celebrating. | 5 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating when I feel bored. | 5 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating when I feel physically uncomfortable. | 5 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating even when traveling/away from home. | 4 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating even when watching TV. | 5 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating even when others around me are eating. | 4 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating even late at night. | 5 ± 3 |

| I can resist eating after a difficult day. | 5 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating when I feel lonely. | 4 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating when celebrating a special occasion. | 5 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating despite a strong craving for a specific food. | 4 ± 2 |

| I can resist eating when I feel sad. | 4 ± 2 |

| Total WEL score | 91 ± 34 |

| Variable | Category | Mean ± SD | 95% CI (Mean) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 87 ± 39 | 77.2 to 96.8 | 0.01 * |

| Female | 94 ± 28 | 86.9 to 101.1 | ||

| Employment | Yes | 93 ± 39 | 84.3 to 101.7 | 0.048 * |

| No | 87 ± 22 | 80.4 to 93.6 | ||

| Health insurance | No insurance | 99 ± 26 | 91.1 to 106.9 | <0.001 * |

| Government insurance | 101 ± 28 | 91.6 to 110.4 | ||

| Private insurance | 71 ± 33 | 57.5 to 84.5 | ||

| Employer-provided | 80 ± 46 | 60.3 to 99.7 | ||

| Payment for tirzepatide | Personal income | 84 ± 30 | 74.7 to 93.3 | <0.001 * |

| Covered by insurance | 93 ± 37 | 80.7 to 105.3 | ||

| Partially covered by insurance | 94 ± 35 | 83.8 to 104.2 | ||

| Duration of use | <1 month | 102 ± 35 | 88.8 to 115.2 | <0.001 * |

| 1–3 months | 89 ± 20 | 82.0 to 96.0 | ||

| 3–6 months | 89 ± 35 | 78.8 to 99.2 | ||

| >6 months | 78 ± 46 | 56.1 to 99.9 | ||

| Previous attempts | No | 92 ± 34 | 85.5 to 98.5 | <0.001 * |

| Diet only | 99 ± 38 | 72.7 to 125.3 | ||

| Fasting | 68 ± 19 | 49.4 to 86.6 | ||

| Physical activities | 71 ± 50 | 22.0 to 120.0 | ||

| Weight loss since tirzepatide | None | 92 ± 11 | 85.2 to 98.8 | 0.003 * |

| <5% | 101 ± 33 | 91.4 to 110.6 | ||

| 5–10% | 83 ± 30 | 72.6 to 93.4 | ||

| >10% | 83 ± 41 | 69.0 to 97.0 |

| Variable | Pearson r | 95% CI (Two-Tailed) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.239 | 0.062 to 0.401 | 0.009 |

| BMI | 0.004 | −0.175 to 0.183 | 0.963 |

| Interview Prompt | Summary of Participant Responses |

|---|---|

| Satisfaction with weight-loss results | Mostly satisfied/very satisfied (visible loss, confidence); a few slower or below expectations. |

| Physical activity changes | Often easier movement/exercise; less breathlessness/fatigue; some unchanged due to low baseline activity. |

| Sleep quality | Frequently improved (deeper, faster onset); some unchanged. |

| Energy levels | Commonly increased energy/reduced fatigue; some unchanged. |

| Mental health/self-confidence | Often improved mood and confidence; some unchanged/continued negative feelings. |

| Motivation to start | Difficulty losing weight, health issues, appearance, and clinician advice. |

| Emotional health overall | Greater self-acceptance/well-being for many; some unchanged. |

| Social interactions | Many reported more participation/encouragement; some reported no change. |

| Side effects (type/severity) | Early mild–moderate GI-type symptoms; occasional severe with dose increases; some none. |

| Impact on daily activities | Typically, the effects are minimal in the first week, with few reported temporary reductions in activity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adam, S.; Ibrahim, F.M.; Dabou, E.A.A.; Pitre, S.; Aiman, R.; AbdelSamad, S. Exploring Adults’ Experiences with Tirzepatide for Weight Loss: A Mixed-Methods Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233102

Adam S, Ibrahim FM, Dabou EAA, Pitre S, Aiman R, AbdelSamad S. Exploring Adults’ Experiences with Tirzepatide for Weight Loss: A Mixed-Methods Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233102

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdam, Shukri, Fatma M. Ibrahim, Eman Abdelaziz Ahmed Dabou, Sneha Pitre, Rania Aiman, and Shimaa AbdelSamad. 2025. "Exploring Adults’ Experiences with Tirzepatide for Weight Loss: A Mixed-Methods Study" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233102

APA StyleAdam, S., Ibrahim, F. M., Dabou, E. A. A., Pitre, S., Aiman, R., & AbdelSamad, S. (2025). Exploring Adults’ Experiences with Tirzepatide for Weight Loss: A Mixed-Methods Study. Healthcare, 13(23), 3102. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233102