Cultural Perceptions and Emotional Well-Being Among Married Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Experiencing Fertility Difficulties in Southern Punjab, Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

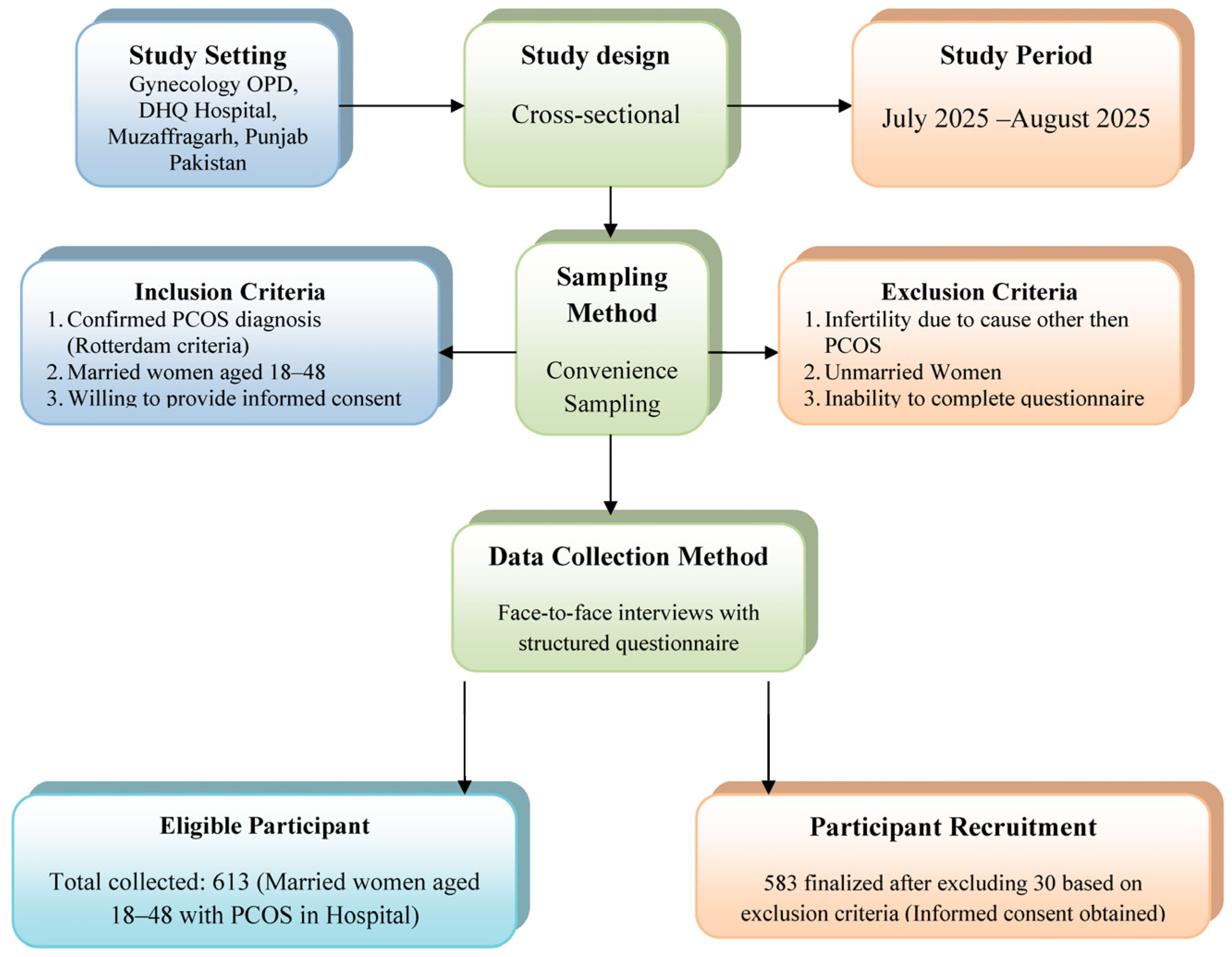

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population and Sampling

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Hypotheses

- H1: Higher perceived cultural importance of having children is associated with poorer emotional well-being among women with PCOS.

- H2: Greater societal pressure to have children soon after marriage is associated with increased anxiety and depression in women with PCOS.

- H3: Negative effects on mental health, including increased anxiety, despair, and coping difficulties, are associated with experiencing stigma or judgment due to fertility issues.

- H4: The belief that fertility difficulties affect a woman’s social status is positively associated with feelings of social isolation and reduced femininity.

- H5: Women with PCOS experience heightened emotional distress when their cultural or religious beliefs significantly influence their perspectives on fertility difficulties.

3. Results

Multiple Regression Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Stener-Victorin, E.; Teede, H.; Norman, R.J.; Legro, R.; Goodarzi, M.O.; Dokras, A.; Laven, J.; Hoeger, K.; Piltonen, T.T. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, M.A.; Surakat, O.A.; Ekundina, V.O.; Jimoh, K.B.; Adeogun, A.E.; Akanji, N.O.; Babalola, O.J.; Eya, P.C. Neglected Tropical Diseases and Female Infertility: Possible Pathophysiological Mechanisms. J. Trop. Med. 2025, 2025, 2126664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kravdal, Ø.; Flatø, M.; Torvik, F.A. Fertility among Norwegian Women and Men with Mental Disorders. Eur. J. Popul. 2025, 41, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltsas, A.; Koumenis, A.; Stavropoulos, M.; Kratiras, Z.; Deligiannis, D.; Adamos, K.; Chrisofos, M. Male Infertility and Reduced Life Expectancy: Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Clinical Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, B.; Sultana, A. Socio-psychological challenges of women having polycystic ovary syndrome. Glob. Sociol. Rev. 2023, 8, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citron, N. The Role of Disclosure and Social Support on Quality of Life in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Master’s Thesis, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Muruthi, B.A.; McRell, A.S.; Cañas, R.E.T.; Lahoti, A.; Zárate, J. “It’s Just Not the Same as Being There”: African Immigrant Women and Their Perspectives on Transnational Mothering. Women Ther. 2025, 48, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uche, N. Ethical and Cultural Challenges in Global Impementation of Assisted Reproduction Technology (ART)—An Integrative Literature Review of the Middle East and Africa. Available online: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-2025061222737 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). State of World Population 2025: The Real Fertility Crisis—The Pursuit of Reproductive Agency in a Changing World; Stylus Publishing, LLC: Sterling, VA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, R.; Lei, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D. Factors associated with stress among pregnant women with a second child in Hunan province under China’s two-child policy: A mixed-method study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Said, H.; Braun-Lewensohn, O. Bedouin adolescents during the Iron Swords War: What strategies help them to cope successfully with the stressful situation? Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladin, M. A Cultural Perspective on the Lived Experience of South Asian American Women with PCOS. Ph.D. Thesis, Fordham University, New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, W.; Tang, L.; Wallis, C. “My Body is Betraying Me”: Exploring the Stigma and Coping Strategies for Infertility Among Women Across Ethnic and Racial Groups. Health Commun. 2025, 40, 2612–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, Z.; Shahid, U.; Levay, A. Understanding the impact of gendered roles on the experiences of infertility amongst men and women in Punjab. Reprod. Health 2013, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.M.; Duerringer, C.M.; Romo, L.K.; Makos, S. Personal responsibility, personal shame: A discourse tracing of individualism about healthcare costs. Rhetor. Health Med. 2023, 6, 64–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardee, K.; Leahy, E. Population, fertility and family planning in Pakistan: A program in stagnation. Popul. Action Int. 2008, 3, 1–12. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237329245_Population_Fertility_and_Family_Planning_in_Pakistan_A_Program_in_Stagnation (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- United Nations Population Fund. Pakistan Population Assessment; Government of Pakistan: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2003. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/216741009_Country_Population_Assessment-Pakistn (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Greenhalgh, S. Anthropology theorizes reproduction: Integrating practice, political economic, and feminist perspectives. In Situating Fertility: Anthropology and Demographic Inquiry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, H.; Ali, S.; Muhammed, D.; Ali, H.; Arshad, S.; Hussain, S.; Daulat, I. Association Between Social Support and Psychological Distress of Parents Having Children with Congenital Heart Disease: Psychological Distress of Parents Having Children with Congenital Heart Disease. NURSEARCHER (J. Nurs. Midwifery Sci.) 2025, 5, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligocka, N.; Chmaj-Wierzchowska, K.; Wszołek, K.; Wilczak, M.; Tomczyk, K. Quality of Life of Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Medicina 2024, 60, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossey, B.; McCaffery, K.J.; Cvejic, E.; Jansen, J.; Copp, T. Understanding the Relationship between Illness Perceptions and Health Behaviour among Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dybciak, P.; Raczkiewicz, D.; Humeniuk, E.; Powrózek, T.; Gujski, M.; Małecka-Massalska, T.; Wdowiak, A.; Bojar, I. Depression in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicińska, A.M.; Maksym, R.B.; Zabielska-Kaczorowska, M.A.; Stachowska, A.; Babińska, A. Immunological and Metabolic Causes of Infertility in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.E.; Moin, A.S.M.; Sathyapalan, T.; Atkin, S.L. A Cross-Sectional Study of Alzheimer-Related Proteins in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Ameeq, M.; Kargbo, A. Prevalence and risk factors of recurrent respiratory infections in a low-and middle-income country: A cross-sectional study on immunodeficiency indicators. Heart Lung 2026, 75, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Sikandar, S.M.; Jamal, F.; Ameeq, M.; Kargbo, A. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia on Inhaled Corticosteroid Therapy: A Comprehensive Analysis of Risk Factors, Disease Burden, and Prevention Strategies. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, S.; Ghayur, M.S.; Karim, R.; Qazi, Q.; Hayat, N.; Wahab, Z. Patterns of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, its Impact on Mental Well-Being, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Marital Satisfaction in Patients Presenting to the Outpatient Departments in Tertiary Care Hospitals of Peshawar. J. Postgrad. Med. Inst. 2025, 39, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Ameeq, M.; Tahir, M.H.; Naz, S.; Fatima, L.; Kargbo, A. Investigating socioeconomic disparities of Kangaroo mother care on preterm infant health outcomes. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 45, 2299982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Ameeq, M.; Fatima, L.; Naz, S.; Sikandar, S.M.; Kargbo, A.; Abbas, S. Assessing socio-ecological factors on caesarean section and vaginal delivery: An extended perspective among women of South-Punjab, Pakistan. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 44, 2252983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category/Statistic | Mean | SD | Category/Statistic | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 32.32 | 7.71 | Have You Been Trying to Conceive? | ||

| Marriage Duration (Years) | 7.50 | 4.50 | Yes | 407 | 69.8 |

| Anxiety About Fertility/PCOS Symptoms | 3.44 | 0.867 | No | 176 | 30.2 |

| Depression/Sadness Due to PCOS/Fertility Difficulties | 2.54 | 1.145 | Faced Difficulties in Conceiving? | ||

| Lack of Control Over Health/Fertility | 2.55 | 1.122 | Yes | 583 | 100.0 |

| Feeling Less Feminine Due to PCOS/Fertility Difficulties | 2.37 | 0.869 | Received Fertility Treatments? | ||

| Social Isolation Due to PCOS/Fertility Challenges | 1.85 | 0.934 | Yes | 583 | 100.0 |

| Difficulty Coping with PCOS Diagnosis | 3.27 | 0.715 | Importance of Having Children in Culture/Community | ||

| Frequency | Percentage | Not Important | 32 | 5.5 | |

| Education Level | Slightly Important | 113 | 19.4 | ||

| No Formal Education | 285 | 48.9 | Moderately Important | 13 | 2.2 |

| Primary/Secondary School | 249 | 42.7 | Very Important | 137 | 23.5 |

| Bachelor’s/Master’s Degree or Above | 49 | 8.4 | Extremely Important | 288 | 49.4 |

| Employment Status | Societal Pressure to Have Children Soon After Marriage | ||||

| Employed | 217 | 37.2 | Rarely | 196 | 33.6 |

| Non-Employed | 1 | 0.2 | Sometimes | 37 | 6.3 |

| Student | 17 | 2.9 | Often | 151 | 25.9 |

| Homeworker | 348 | 59.7 | Always | 199 | 34.1 |

| Socioeconomic Status | Belief Fertility Difficulties Affect Social Status | ||||

| Low | 408 | 70.0 | Strongly Disagree | 42 | 7.2 |

| Middle | 147 | 25.2 | Disagree | 77 | 13.2 |

| High | 28 | 4.8 | |||

| Place of Residence | Neutral | 35 | 6.0 | ||

| Urban | 217 | 37.2 | Agree | 241 | 41.3 |

| Rural | 366 | 62.8 | Strongly Agree | 188 | 32.2 |

| Time Since PCOS Diagnosis | Experienced Stigma or Judgment Due to Fertility Challenges | ||||

| Less than 1 Year | 18 | 3.1 | Never | 11 | 1.9 |

| 1–5 Years | 411 | 70.5 | Rarely | 27 | 4.6 |

| 6–10 Years | 68 | 11.7 | Sometimes | 31 | 5.3 |

| More than 10 Years | 86 | 14.8 | Often | 414 | 71.0 |

| PCOS Symptoms Experienced | Always | 100 | 17.2 | ||

| Irregular Menstrual Cycles | 39 | 6.7 | Cultural/Religious Beliefs Influence Views on Fertility Difficulties | ||

| Hirsutism | 20 | 3.4 | Not at All | 165 | 28.3 |

| Acne | 16 | 2.7 | Slightly | 287 | 49.2 |

| Weight Gain/Obesity | 110 | 18.9 | Moderately | 119 | 20.4 |

| Fertility Difficulties | 100 | 17.2 | Strongly | 8 | 1.4 |

| Polycystic Ovaries | 98 | 16.8 | Very Strongly | 4 | 0.7 |

| Two or More | 200 | 34.3 | |||

| Dependent Variable (Predictor) | β | 95% CI | p-Value | R2 | Adjusted R2 | p-Value (Model) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression/Sadness (H2, H3, H5) | 0.709 | 0.706 | 0.01 | |||

| Importance of Having Children | 0.562 | (0.47)–(0.65) | 0.001 | -- | -- | -- |

| Societal Pressure (H2) | 0.582 | (0.49)–(0.67) | 0.001 | -- | -- | -- |

| Fertility Difficulties Affect Social Status | −0.100 | (−0.17)–(−0.03) | 0.001 | -- | -- | -- |

| Stigma/Judgment (H4) | −0.181 | (−0.27)–(−0.09) | 0.001 | -- | -- | -- |

| Cultural Beliefs (H5) | −0.705 | (−0.82)–(−0.59) | 0.001 | -- | -- | -- |

| Lack of Control (H1, H5) | 0.496 | 0.491 | 0.01 | |||

| Importance of Having Children (H1) | −0.235 | (−0.36)–(−0.11) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Societal Pressure | 0.052 | (−0.03)–(0.13) | 0.20 | -- | -- | -- |

| Fertility Difficulties Affect Social Status | −0.305 | (−0.44)–(−0.17) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Stigma/Judgment | 0.341 | (0.22)–(0.46) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Cultural Beliefs (H5) | −0.520 | (−0.66)–(−0.38) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Feeling Less Feminine (H3) | 0.830 | 0.828 | 0.01 | |||

| Importance of Having Children | 0.557 | (0.46)–(0.65) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Societal Pressure | 0.260 | (0.16)–(0.36) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Fertility Difficulties Affect Social Status (H3) | 0.160 | (0.07)–(0.25) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Stigma/Judgment | 0.042 | (0.00)–(0.08) | 0.03 | -- | -- | -- |

| Cultural Beliefs | 0.308 | (0.21)–(0.41) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Social Isolation (H3, H4, H5) | 0.110 | 0.106 | 0.01 | |||

| Education Level | −0.249 | (−0.35)–(0.15) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Socioeconomic Status | −0.196 | (−0.29)–(−0.10) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Time Since PCOS Diagnosis | 0.014 | (−0.05)–(−0.08) | 0.72 | -- | -- | -- |

| Difficulty Coping (H1, H4, H5) | 0.051 | 0.042 | 0.01 | |||

| Importance of Having Children (H1) | 0.189 | (0.06)–(0.32) | 0.04 | -- | -- | -- |

| Societal Pressure | 0.105 | (−0.01)–(0.22) | 0.06 | -- | -- | -- |

| Fertility Difficulties Affect Social Status | 0.074 | (−0.04)–(0.19) | 0.11 | -- | -- | -- |

| Stigma/Judgment (H3) | −0.055 | (−0.15)–(0.04) | 0.24 | -- | -- | -- |

| Cultural Beliefs (H5) | −0.274 | (−0.39)–(−0.16) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Anxiety About Fertility/PCOS Symptoms | 0.153 | 0.149 | 0.01 | |||

| Education Level | −0.018 | (−0.10)–(0.06) | 0.64 | -- | -- | -- |

| Socioeconomic Status | 0.397 | (0.30)–(0.49) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- |

| Time Since PCOS Diagnosis | −0.035 | (−0.11)–(0.04) | 0.37 | -- | -- | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassan, M.M.; Lim, K.B.; Yeo, S.F.; Ameeq, M. Cultural Perceptions and Emotional Well-Being Among Married Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Experiencing Fertility Difficulties in Southern Punjab, Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3085. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233085

Hassan MM, Lim KB, Yeo SF, Ameeq M. Cultural Perceptions and Emotional Well-Being Among Married Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Experiencing Fertility Difficulties in Southern Punjab, Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3085. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233085

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassan, Muhammad Muneeb, Kah Boon Lim, Sook Fern Yeo, and Muhammad Ameeq. 2025. "Cultural Perceptions and Emotional Well-Being Among Married Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Experiencing Fertility Difficulties in Southern Punjab, Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3085. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233085

APA StyleHassan, M. M., Lim, K. B., Yeo, S. F., & Ameeq, M. (2025). Cultural Perceptions and Emotional Well-Being Among Married Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Experiencing Fertility Difficulties in Southern Punjab, Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(23), 3085. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233085