Unveiling the Financial Burden of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Management in Saudi Arabia: Insights from a Single-Center Study

Abstract

1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Patient Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Collection

- Demographics and History: Age, gender, duration of SLE illness (in years), and presence of comorbid medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension).

- Healthcare Utilization and Costs: Information necessary for the cost estimation, such as prescription medications dispensed, number of hospital admissions and corresponding length of stay (days), types of laboratory tests performed, imaging studies conducted, and frequency of outpatient visits and Emergency Department (ER) visits.

- Disease Activity: SLE disease activity was measured using the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) [15,16]. The SLEDAI-2K is a widely accepted clinical tool that quantifies lupus disease activity over the preceding 10 days [16]. This index incorporates 24 weighted clinical and laboratory manifestations and requires physician assessment and lab results for scoring [15]. Disease activity was stratified based on the SLEDAI-2K scores as follows [16]:

- ○

- No activity: SLEDAI-2K = 0;

- ○

- Mild activity: SLEDAI-2K = 1−5;

- ○

- Moderate activity: SLEDAI-2K = 6−10;

- ○

- High activity: SLEDAI-2K = 11−19;

- ○

- Very high activity: SLEDAI-2K ≥ 20.

2.4. Costing Methodology and Perspective

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Cohort

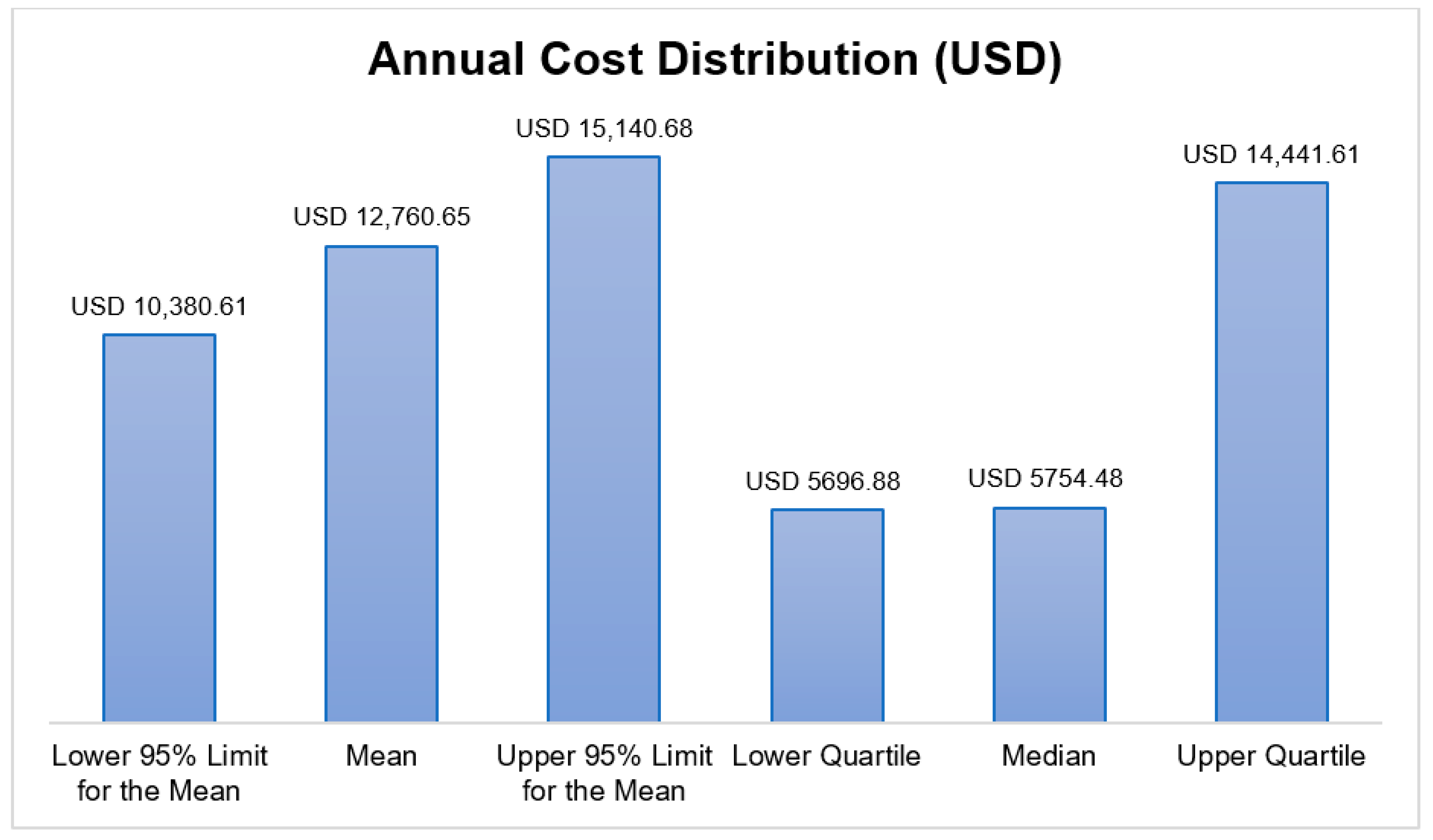

3.2. Annual Direct Medical Cost Distribution

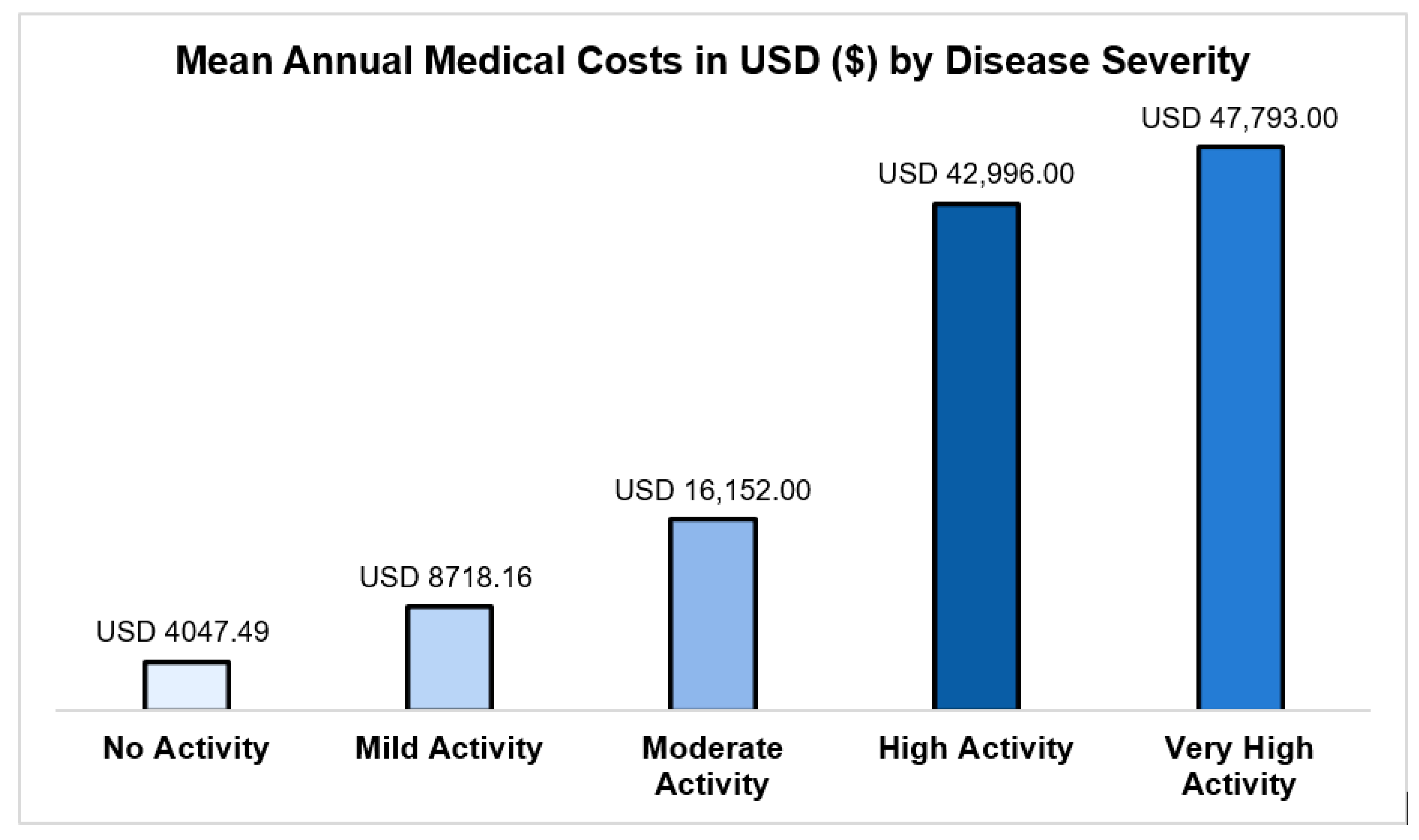

- No activity (SLEDAI-2K = 0): USD 4047 (95% CI: USD 3648–4491);

- Mild activity (SLEDAI-2K = 1–5): USD 8718 (95% CI: USD 7846–9687);

- High activity (SLEDAI-2K = 11–19): USD 42,996 (95% CI: USD 37,764–48,952);

- Very high activity (SLEDAI-2K ≥ 20): USD 47,793 (95% CI: USD 32,736–69,774).

3.3. Predictors of Overall Healthcare Costs

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy Implications

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barber, M.R.; Falasinnu, T.; Ramsey-Goldman, R.; Clarke, A.E. The global epidemiology of SLE: Narrowing the knowledge gaps. Rheumatology 2023, 62 (Suppl. 1), i4–i9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhang, D.; Yao, X.; Huang, Y.; Lu, Q. Global epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: A comprehensive systematic analysis and modelling study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shujairi, A.; Elbadawi, F.; Al-Saleh, J.; Hamouda, M.; Vasylyev, A.; Khamashta, M. Literature review of lupus nephritis From the Arabian Gulf region. Lupus 2023, 32, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Dhanhani, A.M.; Agarwal, M.; Othman, Y.S.; Bakoush, O. Incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus among the native Arab population in UAE. Lupus 2017, 26, 664–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Arfaj, A.S.; Al-Balla, S.R.; Al-Dalaan, A.N.; Al-Saleh, S.S.; Bahabri, S.A.; Mousa, M.M.; Sekeit, M.A. Prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2002, 23, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Albishri, J.; Bukhari, M.; Alsabban, A.; Almalki, F.A.; Altwairqi, A.S. Prevalence of RA and SLE in Saudi Arabia. Sch. J. App Med. Sci. 2015, 3, 2096–2099. [Google Scholar]

- Manasfi, H.O.; Alanazi, W.S.; Almaghrabi, A.N.; Alqahtani, F.S.; Alawar, M.T.A.; Abbushi, Q.M.J. Demographics and clinical manifestations of lupus patients: Experience from a private hospital in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Dev. Ctries. 2024, 8, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, R.A.; Aljanobi, G.A.; Alderaan, K.; Omair, M.A. Exploring the quality of life and comorbidity impact among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2024, 45, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenzi, F.; Aljohani, R.; Aboabat, A.; Alanazi, F.; Almalag, H.M.; Omair, M.A. Systematic review of the reporting of extrarenal manifestations in observational studies of Saudi patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus Sci. Med. 2025, 12, e001469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adwan, M. Clinical and serologic characteristics of systemic lupus erythematosus in the Arab world: A pooled analysis of 3273 patients. Arch. Rheumatol. 2018, 33, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, R.; Alenzi, F.; Aboabat, A.; Alanazi, F.; Almalag, H.M.; Alrowaie, F.A.; Omair, M.A. Disease characteristics and outcomes of lupus nephritis in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Lupus 2025, 34, 1184–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katarzyna, P.-B.; Wiktor, S.; Ewa, D.; Piotr, L. Current treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: A clinician’s perspective. Rheumatol. Int. 2023, 43, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alansari, A.; Hannawi, S.; Aldhaheri, A.; Zamani, N.; Elsisi, G.H.; Aldalal, S.; Naeem, W.A.; Farghaly, M. The economic burden of systemic lupus erythematosus in United Arab Emirates. J. Med. Econ. 2024, 27, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karremah, M.F.; Hassan, R.Y.; Faloudah, A.Z.; Alharbi, L.K.; Shodari, A.F.; Rahbeeni, A.A.; Alharazi, N.K.; Binjabi, A.Z.; Cheikh, M.M.; Manasfi, H.; et al. From Symptoms to Diagnosis: An Observational Study of the Journey of SLE Patients in Saudi Arabia. Open Access Rheumatol. 2022, 14, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladman, D.D.; Ibaņez, D.; Urowitz, M.B. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J. Rheumatol. 2002, 29, 288–291. [Google Scholar]

- Mosca, M.; Bombardieri, S. Assessing remission in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2006, 24, S99. [Google Scholar]

- CCHI. Health Services Prices Based on Saudi CCHI; CCHI: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- AlRuthia, Y.; Almutiri, N.M.; Almutairi, R.M.; Almohammed, O.; Alhamdan, H.; El-Haddad, S.A.; Asiri, Y.A. Local causes of essential medicines shortages from the perspective of supply chain professionals in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb, P.; Norton, E.C. Modeling Health Care Expenditures and Use. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2018, 39, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; Dunn, L. The declaration of Helsinki on medical research involving human subjects: A review of seventh revision. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2019, 17, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Near, A.M.; Desta, B.; Wang, X.; Hammond, E.R. Disease and economic burden increase with systemic lupus erythematosus severity 1 year before and after diagnosis: A real-world cohort study, United States, 2004–2015. Lupus Sci. Med. 2021, 8, e000503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jang, E.J.; Cho, S.K.; Han, J.Y.; Jeon, Y.; Jung, S.Y.; Sung, Y.K. Cost-of-illness changes before and after the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus: A nationwide, population-based observational study in Korea. Rheumatology 2025, 64, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, H.J.; Song, X.; Johnson, B.H.; Bechtel, B.; O’Sullivan, D.; Molta, C.T. Healthcare utilization and costs of systemic lupus erythematosus in Medicaid. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 808391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, M.R.W.; Ugarte-Gil, M.F.; Hanly, J.G.; Urowitz, M.B.; St-Pierre, Y.; Gordon, C.; Bae, S.C.; Romero-Diaz, J.; Sanchez-Guerrero, J.; Bernatsky, S.; et al. Remission and low disease activity are associated with lower healthcare costs: Results from the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) inception cohort. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 1295–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murimi-Worstell, I.B.; Lin, D.H.; Kan, H.; Tierce, J.; Wang, X.; Nab, H.; Desta, B.; Alexander, G.C.; Hammond, E.R. Healthcare utilization and costs of systemic lupus erythematosus by disease severity in the United States. J. Rheumatol. 2021, 48, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, L.; Fabry-Vendrand, C.; Todea, R.; Vidal, B.; Cottin, J.; Bureau, I.; Bouée, S.; Thabut, G. Economic burden of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis in France: A nationwide population-based study using the French medico-administrative (SNDS) claims database. Jt. Bone Spine 2025, 92, 105827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, M.; Zou, K.; Wang, Y.; Jia, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Wu, C.; Wang, Q.; Tian, X.; et al. Annual Direct Cost and Cost-Drivers of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Multi-Center Cross-Sectional Study from CSTAR Registry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuwayegh, A.; Almaghlouth, I.A.; Almasaoud, M.A.; Alzaid, A.S.; Alsuhaibani, A.A.; Almana, L.H.; Alabdulkareem, S.M.; Abudahesh, J.A.; AlRuthia, Y. Cost Consequence Analysis of Belimumab versus Standard of Care for the Management of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Saudi Arabia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galoppini, G.; Marangoni, A.; Cirilli, F.; Ruffilli, F.; Garaffoni, C.; Govoni, M.; Scirè, C.A.; Silvagni, E.; Bortoluzzi, A. Optimizing Patient Care: A Systematic Review of Multidisciplinary Approaches for SLE Management. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRuthia, Y.; Aldallal, S.; Al-Abdulkarim, H.A.; Al-Jedai, A.; Almudaiheem, H.; Hamad, A.; Elmusharaf, K.; Saadi, M.; Al Awar, H.; Al Sabbah, H. Healthcare systems and health economics in GCC countries: Informing decision-makers from the perspective of the Gulf health economics association. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1510401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Anezi, F.M.; Alrajhi, S.; Al-Anezi, N.M.; Alabbadi, D.M.; Almana, R. A review of healthcare system in Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the 2020 19th International Symposium on Distributed Computing and Applications for Business Engineering and Science (DCABES), Xuzhou, China, 16–19 October 2020; pp. 318–322. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age groups | |

| 20–39 years | 47 (45.63) |

| 40–59 years | 51 (49.51) |

| ≥60 years | 5 (4.85) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 (9.71) |

| Female | 93 (90.29) |

| Nationality | |

| Saudi | 100 (97.09) |

| Non-Saudi | 3 (2.91) |

| Smoking status | |

| Smoker | 13 (12.62) |

| Non-smoker | 90 (87.38) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 41 (39.81) |

| Married | 55 (53.40) |

| Disease duration | |

| <5 years | 4 (3.88) |

| 5–9 years | 28 (27.18) |

| ≥10 years | 71 (68.93) |

| Disease complications | |

| Proteinuria | 21 (20.39) |

| Hemolytic anemia | 6 (5.83) |

| Leukopenia | 21 (20.39) |

| Arthritis | 45 (43.69) |

| Serositis | 6 (5.83) |

| Lupus nephritis | 45 (43.69) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 13 (12.62) |

| Alopecia | 23 (22.33) |

| Neurological symptoms | 9 (8.74) |

| Chronic cutaneous lupus | 21 (20.39) |

| Baseline systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index (SLEDAI-2K) | |

| No activity (SLEDAI = 0) | 21 (20.39) |

| Mild activity (SLEDAI = 1 to 5) | 41 (39.81) |

| Moderate activity (SLEDAI = 6 to 10) | 26 (25.24) |

| High activity (SLEDAI = 11 to 19) | 14 (13.59) |

| Very high activity (SLEDAI ≥ 20) | 1 (0.97) |

| Characteristic | Cost (USD) | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Age | |||

| 20–39 years | 16,614 | 14,873 | 18,560 |

| 40–59 years | 15,973 | 14,214 | 17,949 |

| ≥60 years | 16,494 | 13,668 | 19,904 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 16,108 | 13,859 | 18,722 |

| Female | 16,612 | 14,871 | 18,557 |

| Disease Activity | |||

| No activity | 4047.49 | 3647.82 | 4490.96 |

| Mild | 8718.16 | 7846.39 | 9686.80 |

| Moderate | 16,152 | 14,553 | 17,928 |

| High | 42,996 | 37,764 | 48,952 |

| Very high | 47,793 | 32,736 | 69,774 |

| Duration of Illness | |||

| <5 years | 16,771 | 13,748 | 20,458 |

| 5–9 years | 16,537 | 14,548 | 18,798 |

| ≥10 years | 15,782 | 14,064 | 17,711 |

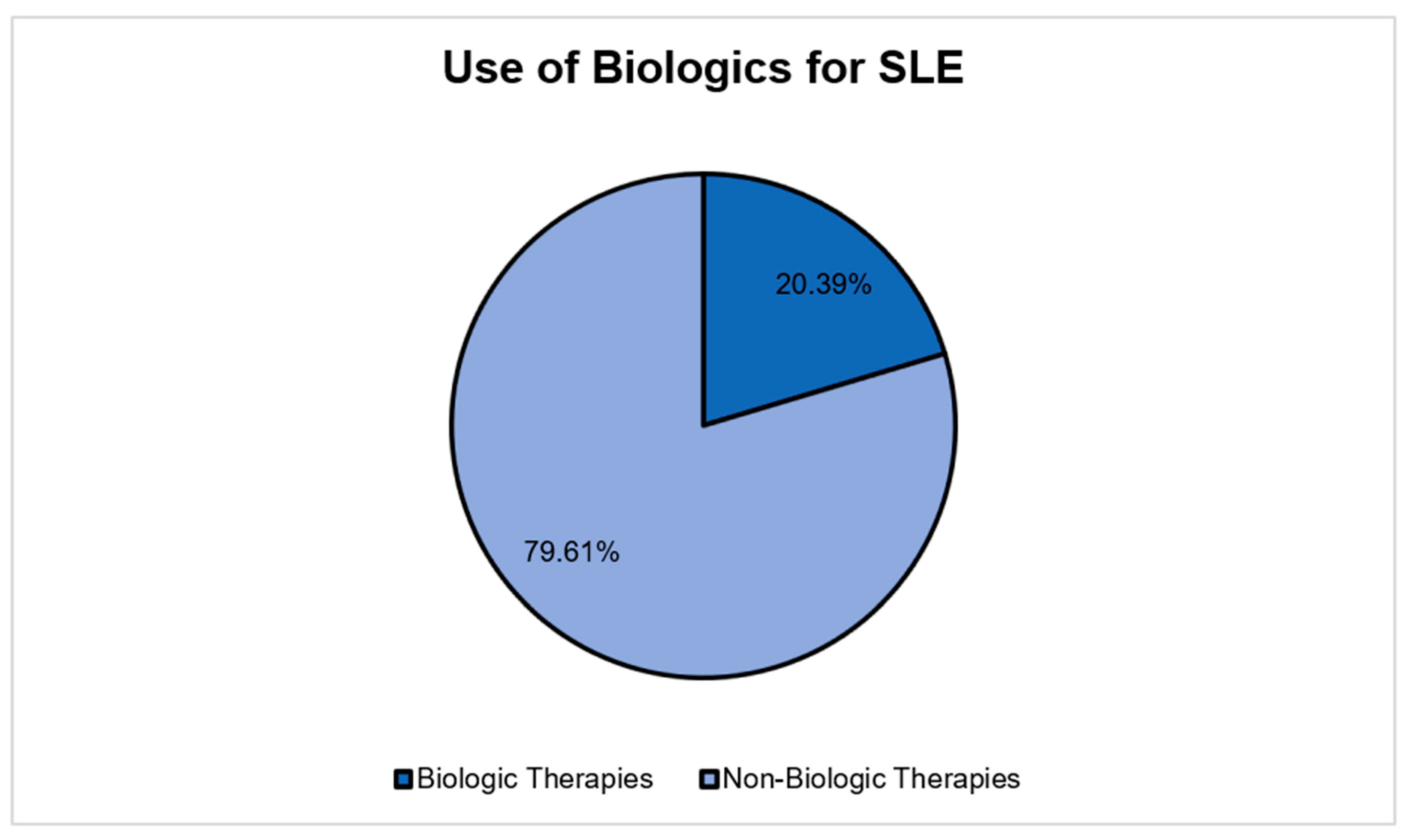

| Use of Biologics | |||

| No | 11,613 | 10,352 | 13,029 |

| Yes | 23,041 | 20,049 | 26,480 |

| Variable | Estimate | 95% Confidence Limits | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age | −0.0028 | −0.0060 | 0.0004 | 0.091 |

| Duration of illness | −0.0018 | −0.0076 | 0.0039 | 0.532 |

| Gender (male versus female) | −0.0102 | −0.1351 | 0.1147 | 0.873 |

| Disease activity | 0.7397 | 0.7024 | 0.7771 | <0.001 * |

| Use of biologics | 0.7080 | 0.6146 | 0.8013 | <0.001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alsuwayegh, A.; AlRuthia, Y. Unveiling the Financial Burden of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Management in Saudi Arabia: Insights from a Single-Center Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3075. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233075

Alsuwayegh A, AlRuthia Y. Unveiling the Financial Burden of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Management in Saudi Arabia: Insights from a Single-Center Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3075. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233075

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsuwayegh, Aseel, and Yazed AlRuthia. 2025. "Unveiling the Financial Burden of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Management in Saudi Arabia: Insights from a Single-Center Study" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3075. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233075

APA StyleAlsuwayegh, A., & AlRuthia, Y. (2025). Unveiling the Financial Burden of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Management in Saudi Arabia: Insights from a Single-Center Study. Healthcare, 13(23), 3075. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233075