Can Pets Prevent Suicide? The Impact of Companion Animals on Suicidality: Scoping Review and Clinical Recommendations

Highlights

- Companion animals have been found to impact suicide risk.

- Suicide prevention strategies may benefit from the incorporation of companion animals.

- Future research is needed to better understand the connection between companion animals and suicide risk.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Objectives

1.2. Research Question

2. Methods and Analysis

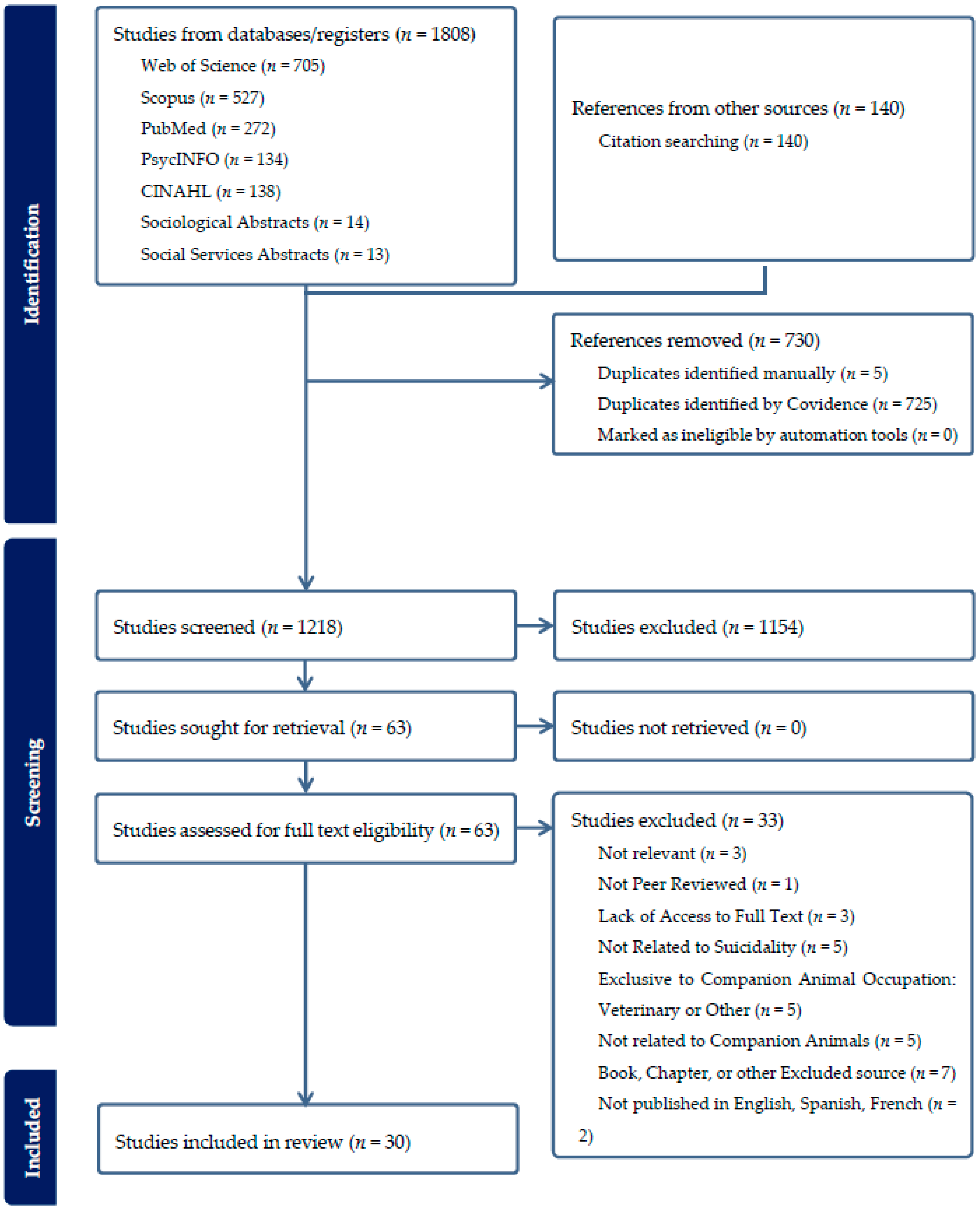

Study Selection

3. Results

3.1. Impact on Suicidality

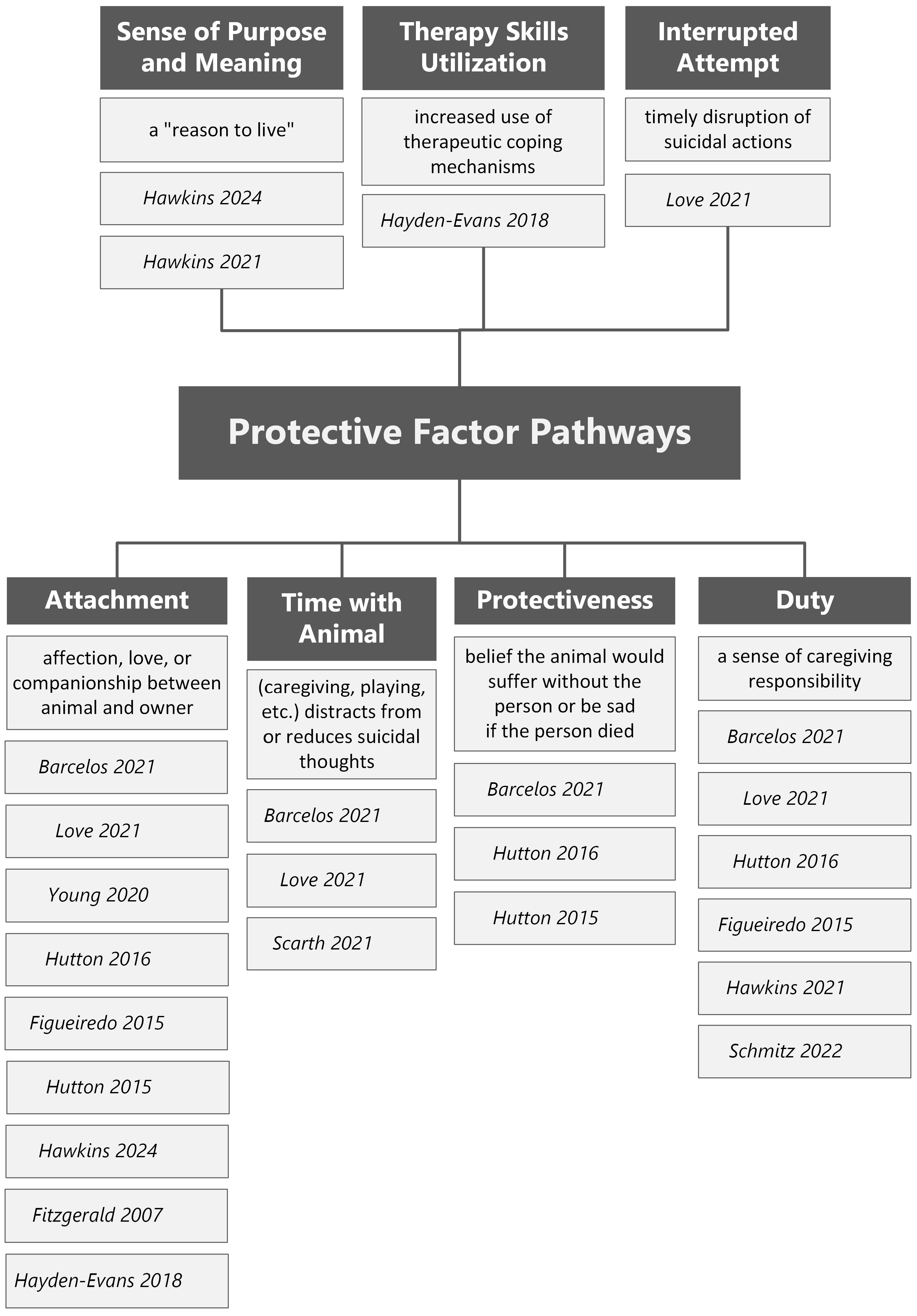

3.1.1. Pets as Protective Factors

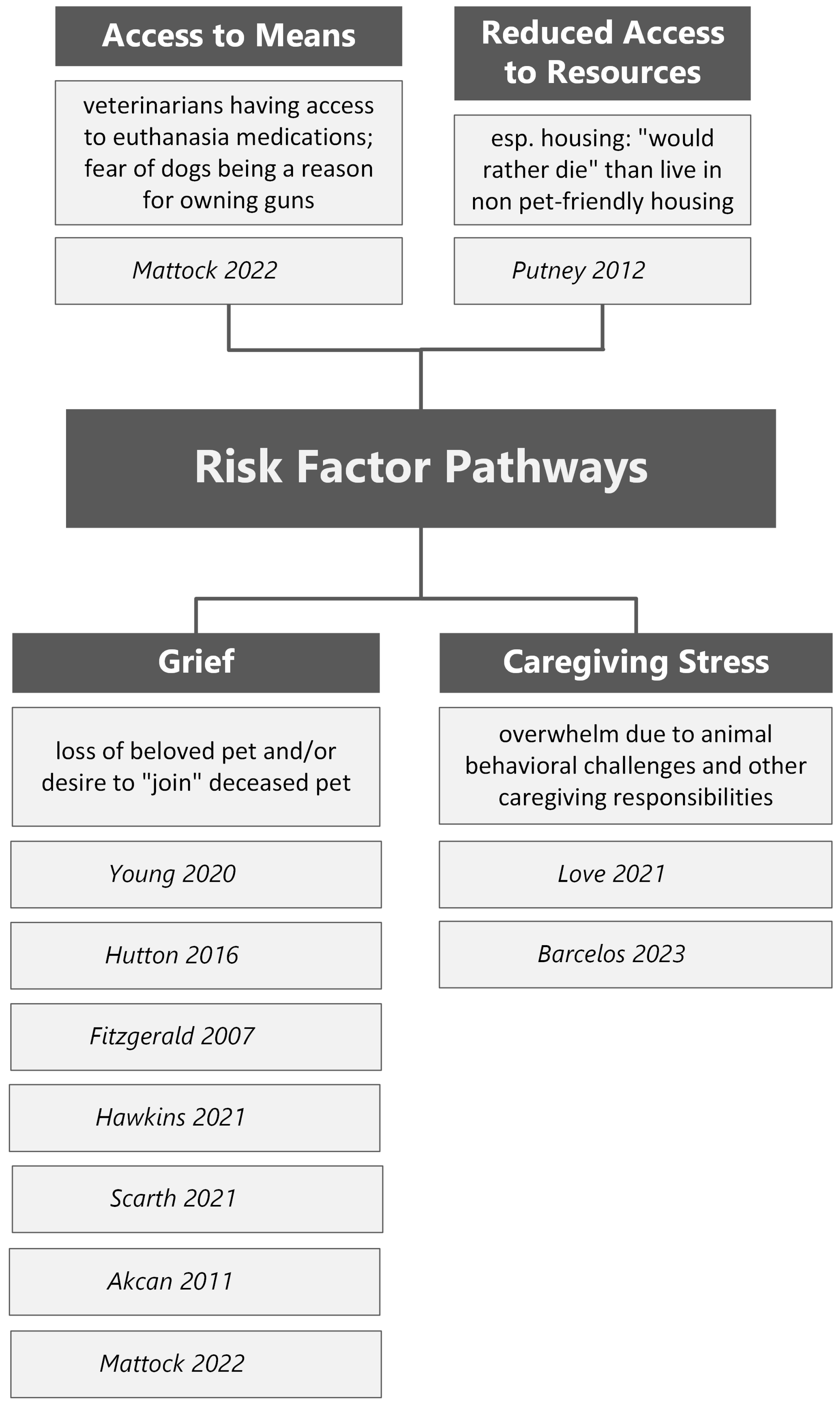

3.1.2. Pets as Risk Factors

3.1.3. Pets’ Inconclusive Impact

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Incorporating Pets into Suicide Risk Assessments

4.3. Incorporating Pets into Suicide Safety Plans

4.4. Need for Resources

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | First Author | Article Title | Journal | Published Language | Country | Study Design | Reported Impact of Companion Animals on Suicidality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Hayden-Evans [35] | Pets provide meaning and purpose’: A qualitative study of pet ownership from the perspectives of people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder | Advances in Mental Health | English | Australia | Qualitative research | Protective Factor |

| 2022 | Schmitz [37] | Companion, friend, four-legged fluff ball’: The power of pets in the lives of LGBTQ+ young people experiencing homelessness | Sexualities | English | United States | Qualitative research | Protective Factor |

| 2014 | Hasegawa [48] | Assisted suicide and killing of a household pet: Pre-autopsy post-mortem imaging of a victim and a dog | Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology | English | Germany | Case report | Inconclusive or Unclear Impact |

| 2012 | Putney [42] | “Souldog”: The perceived impact of companion animals on older lesbian adults | UMI Dissertation Publishing/ProQuest | English | United States | Qualitative research | Inconclusive or Unclear Impact |

| 2007 | Fitzgerald [34] | “They gave me a reason to live”: The protective effects of companion animals on the suicidality of abused women | Humanity & Society | English | Canada | Qualitative research | Protective Factor |

| 2023 | Douglas [55] | Pet attachment and the interpersonal theory of suicide | Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention | English | United States | Cross-sectional study | Protective Factor; Risk Factor; No Impact |

| 2022 | El Frenn [56] | Association of the time spent on social media news with depression and suicidal ideation among a sample of Lebanese adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Lebanese economic crisis | Current Psychology | English | Lebanon | Cross-sectional study | Inconclusive or Unclear Impact |

| 2009 | Hagemeier [49] | Extended suicide using an atypical stud gun | Forensic Science International | English | Germany | Case report | Inconclusive or Unclear Impact |

| 2022 | Teimouri [46] | Prevalence and predictors of Toxoplasma gondii infection in psychiatric inpatients in Fars Province, Southern Iran | Frontiers in Psychiatry | English | Iran | Cross-sectional study | Inconclusive or Unclear Impact |

| 2011 | Akcan [39] | Unexpected suicide and irrational thinking in adolescence: A case report | Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine | English | Turkey | Case report | Risk Factor |

| 2024 | Hawkins [33] | Young adults’ views on the mechanisms underpinning the impact of pets on symptoms of anxiety and depression | Frontiers in Psychiatry | English | United Kingdom | Qualitative research | Protective Factor |

| 2015 | Hutton [32] | Social provisions of the human-animal relationship amongst 30 people living with HIV in Australia | Anthrozoos | English | Australia | Qualitative research | Protective Factor |

| 2023 | Barcelos [41] | Dog owner mental health is associated with dog behavioural problems, dog care and dog-facilitated social interaction: a prospective cohort study | Scientific Reports | English | United Kingdom | Cohort study | Risk Factor |

| 2015 | Figueiredo [31] | Is it possible to overcome suicidal ideation and suicide attempts? A study of the elderly | Cien Saude Colet | Other | Brazil | Qualitative research | Protective Factor |

| 1985 | Helsing [57] | Dog and cat ownership among suicides and matched controls | American Journal of Public Health | English | United States | Cross-sectional study | No Impact |

| 2014 | Roseneil [58] | On meeting Linda: An intimate encounter with (not-)belonging in the current conjuncture | Psychoanalysis, Culture, and Society | English | United Kingdom | Case report | Inconclusive or Unclear Impact |

| 2018 | Sarlon [59] | Vegetative symptoms and behaviour of the therapy-accompanying dog of a chronically suicidal patient | BMJ Case Reports | English | Germany | Case report | Protective Factor |

| 2021 | Scanlon [60] | Homeless people and their dogs: Exploring the nature and impact of the human-companion animal bond | Anthrozoos | English | United Kingdom | Qualitative research | Inconclusive or Unclear Impact |

| 2023 | Smith [61] | Links between pet ownership and exercise on the mental health of veterinary professionals | Vet Record Open | English | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional study | No Impact |

| 2021 | Palazzo [47] | Integrated multidisciplinary approach in a case of occupation related planned complex suicide–peticide | Legal Medicine | English | Italy | Case report | Inconclusive or Unclear Impact |

| 2013 | Cooke [50] | Extended suicide with a pet | Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry | English | United States | Case report | Inconclusive or Unclear Impact |

| 2016 | Hutton [30] | What am I going to do without him?’: Death anxiety, projection, and the human-animal relationship | Psychoanalytic Review | English | Australia | Case series | Protective Fator; Risk Factor |

| 2020 | Young [29] | A qualitative analysis of pets as suicide protection for older people | Anthrozoos | English | Australia | Qualitative research | Protective Factor; Risk Factor |

| 2021 | Love [28] | Best friends come in all breeds: The role of pets in suicidality | Anthrozoos | English | United States | Qualitative research | Protective Factor; Risk Factor; No Impact |

| 2021 | Hawkins [36] | I can’t give up when I have them to care for’: People’s experiences of pets and their mental health | Anthrozoos | English | United Kingdom | Qualitative research | Protective Factor; Risk Factor |

| 2022 | Mattock [40] | Discourses and silences: Pets in publicly accessible coroners’ reports of Australian suicides | Anthrozoos | English | Australia | Qualitative research | Risk Factor; No Impact |

| 2023 | Young [51] | Peticide: An analysis of online news media articles of human suicide involving pet animals | Anthrozoos | English | United Kingdom; United States; Australia | Qualitative research | Inconclusive or Unclear Impact |

| 2021 | Scarth [38] | Strategies to stay alive: Adaptive toolboxes for living well with suicidal behavior | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | English | United States | Qualitative research | Protective Factor; Risk Factor |

| 2019 | Williamson [54] | An exploratory analysis of self-reported protective factors against self-harm in an enrolled veteran general mental health population | Military Medicine | English | United States | Cross-sectional study | Protective Factor |

| 2021 | Barcelos [27] | Understanding the impact of dog ownership on autistic adults: Implications for mental health and suicide prevention | Scientific Reports | English | United Kingdom | Qualitative research | Protective Factor |

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide [Fact sheet]. 25 March 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts About Suicide. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/index.html (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, HHS Publication No. PEP23-07-01-006, NSDUH Series H-58). 2023. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2022-nsduh-annual-national-report (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs. 2024 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2024/2024-Annual-Report-Part-2-of-2_508.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Garnett, M.F.; Curtin, S.C. Suicide Mortality in the United States, 2001–2021. National Center for Health Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db464.htm (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Ki, M.; Lapierre, S.; Gim, B.; Hwang, M.; Kang, M.; Dargis, L.; Jung, M.; Koh, E.J.; Mishara, B. A systematic review of psychosocial protective factors against suicide and suicidality among older adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2024, 36, 346–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielassoff, E.; Le Floch, M.; Avril, C.; Gohier, B.; Duverger, P.; Riquin, E. Protective factors of suicidal behaviors in children and adolescents/young adults: A literature review. Arch. Pediatr. Organe Off. Soc. Fr. Pediatr. 2023, 30, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, J.; Maxwell, M.; Platt, S.; Harris, F.; Jepson, R. Risk and Protective Factors for Suicide and Suicidal Behaviour: A Literature Review; Social Research; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2008.

- Joiner, T.E. Why People Die by Suicide; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden, K.A.; Witte, T.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Braithwaite, S.R.; Selby, E.A.; Joiner, T.E., Jr. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, G.N.; Allen, K.; Braun, L.T.; Christian, H.E.; Friedmann, E.; Taubert, K.A.; Thomas, S.A.; Wells, D.L.; Lange, R.A. Pet ownership and cardiovascular risk: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013, 127, 2353–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.C.J.; Wallace, E.J.; Pater, R.; Gross, D.P. Evaluating the relationship between well-being and living with a dog for people with chronic low back pain: A feasibility study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1472–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, E.; Son, H. The human-companion animal bond: How humans benefit. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2009, 39, 293–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, L.; Edwards, K.M.; McGreevy, P.; Bauman, A.; Podberscek, A.; Neilly, B.; Sherrington, C.; Stamatakis, E. Companion dog acquisition and mental well-being: A community-based three-arm controlled study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Census Bureau. 2021 Household Pets. 2022. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2022/demo/2021-household-pets.html (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Wheeler, E.A.; Faulkner, M.E. The “pet effect”: Physiological calming in the presence of canines. Soc. Anim. J. Hum.-Anim. Stud. 2015, 23, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, H.; Rushton, K.; Walker, S.; Lovell, K.; Rogers, A. Ontological security and connectivity provided by pets: A study in the self-management of the everyday lives of people diagnosed with a long-term mental health condition. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.H. How do cat owners, dog owners and individuals without pets differ in terms of psychosocial outcomes among individuals in old age without a partner? Aging Ment. Health 2019, 24, 1613–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, Y.; Seino, S.; Nishi, M.; Tomine, Y.; Tanaka, I.; Yokoyama, Y.; Amano, H.; Kitamura, A.; Shinkai, S. Correction: Physical, social, and psychological characteristics of community-dwelling elderly Japanese dog and cat owners. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, I.H.; Conwell, Y.; Bowen, C.; Van Orden, K.A. Pet ownership may attenuate loneliness among older adult primary care patients who live alone. Aging Ment. Health 2013, 18, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, K. The relationship between companion animals and loneliness among rural adolescents. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2012, 27, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkin, J.; Van Buiten, H.; Turner, C.; Gandenberger, J.; Nieforth, L.; Taeckens, A.; Watkins, K. A scoping review protocol on existing research on the effects of companion animals on suicide and suicidality. 8 October 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mak, S.; Thomas, A. An Introduction to Scoping Reviews. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Borkar, N.K. Significance of including grey literature search in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2023, 17, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia, 2025. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Barcelos, A.M.; Kargas, N.; Packham, C.; Mills, D.S. Understanding the impact of dog ownership on autistic adults: Implications for mental health and suicide prevention. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, H.A. Best friends come in all breeds: The role of pets in suicidality. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.; Bowen-Salter, H.; O’Dwyer, L.; Stevens, K.; Nottle, C.; Baker, A. A qualitative analysis of pets as suicide protection for older people. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, V.E. “What am I going to do without him?”: Death anxiety, projection, and the human–animal relationship. Psychoanal. Rev. 2016, 103, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, A.E.B.; Silva, R.M.; Vieira, L.J.E.S.; Mangas, R.M.D.N.; Sousa, G.S.; Freitas, J.S.; Conte, M.; Sougey, E.B. Is it possible to overcome suicidal ideation and suicide attempts? A study of the elderly. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2015, 20, 1711–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, V.E. Social provisions of the human-animal relationship amongst 30 people living with HIV in Australia. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.D.; Kuo, C.; Robinson, C. Young adults’ views on the mechanisms underpinning the impact of pets on symptoms of anxiety and depression. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1355317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, A.J. “They gave me a reason to live”: The protective effects of companion animals on the suicidality of abused women. Humanit. Soc. 2007, 31, 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden-Evans, M.; Milbourn, B.; Netto, J. “Pets provide meaning and purpose”: A qualitative study of pet ownership from the perspectives of people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. Adv. Ment. Health 2018, 16, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.D.; Hawkins, E.L.; Tip, L. “I can’t give up when I have them to care for”: People’s experiences of pets and their mental health. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R.M.; Carlisle, Z.T.; Tabler, J. “Companion, friend, four-legged fluff ball”: The power of pets in the lives of LGBTQ+ young people experiencing homelessness. Sexualities 2022, 25, 694–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarth, B.; Bering, J.M.; Marsh, I.; Santiago-Irizarry, V.; Andriessen, K. Strategies to stay alive: Adaptive toolboxes for living well with suicidal behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçan, R.; Arslan, M.M.; Cekin, N.; Karanfil, R. Unexpected suicide and irrational thinking in adolescence: A case report. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2011, 18, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattock, K.; Young, J.; Bould, E. Discourses and silences: Pets in publicly accessible coroners’ reports of Australian suicides. Anthrozoös 2022, 35, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, A.M.; Kargas, N.; Assheton, P.; Maltby, J.; Hall, S.; Mills, D.S. Dog owner mental health is associated with dog behavioural problems, dog care and dog-facilitated social interaction: A prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putney, J.M. “Souldog”: The Perceived Impact of Companion Animals on Older Lesbian Adults. Doctoral Thesis, Simmons College School of Social Work, Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Toxoplasmosis: Causes. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/toxoplasmosis/causes/index.html (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Godwin, R. Toxoplasma gondii and elevated suicide risk. Vet. Rec. 2012, 171, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postolache, T.T.; Duncan, E.; Yen, P.; Potocki, E.; Barnhart, M.; Federline, A.; Massa, N.; Dagdag, A.; Joseph, J.; Wadhawan, A.; et al. Toxoplasma gondii, suicidal behaviour and suicide risk factors in US Veterans enrolled in mental health treatment. Folia Parasitol. 2025, 72, 2025.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, A.; Nassrullah, O.J.; Hedayati, P.; Bahreini, M.S.; Alimi, R.; Mohtasebi, S.; Salemi, A.M.; Asgari, Q. Prevalence and predictors of Toxoplasma gondii infection in psychiatric inpatients in Fars Province, southern Iran. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 891603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzo, C.; Pascali, J.P.; Pelletti, G.; Mazzotti, M.C.; Fersini, F.; Pelotti, S.; Fais, P. Integrated multidisciplinary approach in a case of occupation-related planned complex suicide-peticide. Leg. Med. 2021, 48, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, I.; Gehl, A.; Nushida, H.; Püschel, K. Assisted suicide and killing of a household pet: Pre-autopsy post-mortem imaging of a victim and a dog. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2014, 10, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemeier, L.; Schyma, C.; Madea, B. Extended suicide using an atypical stud gun. Forensic Sci. Int. 2009, 189, e9–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, B.K. Extended suicide with a pet. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2013, 41, 437–443. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24051598/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Young, J.; Oxley, J.A.; Montrose, V.T.; Herzog, H. Peticide: An analysis of online news media articles of human suicide involving pet animals. Anthrozoös 2023, 36, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, K.E.; Herzog, H.; Gee, N.R. Variability in Human-Animal Interaction Research. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 7, 619600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, H. The Impact of Pets on Human Health and Psychological Well-Being: Fact, Fiction, or Hypothesis? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A.K.; Riendeau, R.P.; Stolzmann, K.; Silverman, A.F.; Kim, B.; Miller, C.J.; Connolly, S.L.; Pitcock, J.; Bauer, M.S. An exploratory analysis of self-reported protective factors against self-harm in an enrolled veteran general mental health population. Mil. Med. 2019, 184, e738–e744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, V.J.; Kwan, M.Y.; Gordon, K.H. Pet attachment and the interpersonal theory of suicide. Crisis 2023, 44, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Frenn, Y.; Hallit, S.; Obeid, S.; Soufia, M. Association of the time spent on social media news with depression and suicidal ideation among a sample of Lebanese adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Lebanese economic crisis. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 20638–20650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsing, K.J.; Monk, M. Dog and cat ownership among suicides and matched controls. Am. J. Public Health 1985, 75, 1223–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseneil, S. On meeting Linda: An intimate encounter with (not-)belonging in the current conjuncture. Psychoanal. Cult. Soc. 2014, 19, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlon, J.; Staniloiu, A.; Schöntges, A.; Kordon, A. Vegetative symptoms and behaviour of the therapy-accompanying dog of a chronically suicidal patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, 2018, bcr-2018-225483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlon, L.; Hobson-West, P.; Cobb, K.; McBride, A.; Stavisky, J. Homeless people and their dogs: Exploring the nature and impact of the human–companion animal bond. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.T.; Barcelos, A.M.; Mills, D.S. Links between pet ownership and exercise on the mental health of veterinary professionals. Vet. Rec. Open 2023, 10, e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Sub-Category | N = Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Human Demographics | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Did not report | 21 | |

| Bi- or Multi-Racial | 2 | |

| White/Caucasian | 6 | |

| Native American | 3 | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 | |

| Black | 3 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 | |

| Middle Eastern | 1 | |

| Asian | 2 | |

| Other | 1 | |

| Life Stage | ||

| Adult | 21 | |

| Elder | 5 | |

| Adolescent/Young Adult | 3 | |

| Did not report | 2 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 22 | |

| Female | 28 | |

| Transgender Male | 2 | |

| Transgender Female | 2 | |

| Two-spirit | 1 | |

| Non-binary | 4 | |

| Other * | 4 | |

| Unknown/prefer not to say | 1 | |

| Educational Level of Study | ||

| Did not report | 26 | |

| Some college education (with or without degree) | 3 | |

| High school (with or without diploma) | 1 | |

| Secondary school (grades 6–9) | 2 | |

| Primary/elementary (grades 1–5) | 2 | |

| Mental Health Diagnoses | ||

| Did not report | 13 | |

| Personality disorder | 2 | |

| Depression | 10 | |

| Suicidal ideation or suicide attempts | 8 | |

| Anxiety disorder | 6 | |

| Bipolar disorder | 2 | |

| Schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder | 4 | |

| Obsessive/compulsive disorder | 2 | |

| Substance use disorder | 1 | |

| Post-traumatic stress | 2 | |

| Panic disorder or panic attacks | 1 | |

| Neurodivergence or autism spectrum disorder | 2 | |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 1 | |

| Eating disorder | 1 | |

| Paranoia | 1 | |

| Unspecified mental or physical health condition | 2 | |

| Veteran Status | ||

| Did not report | 29 | |

| United States Veteran | 1 | |

| Animal Demographics | ||

| Species | ||

| Dog | 24 | |

| Cat | 15 | |

| Horse | 7 | |

| Other farm animal | 3 | |

| Reptile | 5 | |

| Amphibians | 3 | |

| Fish | 9 | |

| Pet Ownership | ||

| Pet belonged to study participant | 23 | |

| Pet belonged to family member | 3 | |

| Pet belonged to other member of household | 4 | |

| Unclear or not reported | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Buiten, H.; Turner, C.; Gandenberger, J.; Forkin, J.; Taeckens, A.; Morris, K.N.; Nieforth, L.O. Can Pets Prevent Suicide? The Impact of Companion Animals on Suicidality: Scoping Review and Clinical Recommendations. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233067

Van Buiten H, Turner C, Gandenberger J, Forkin J, Taeckens A, Morris KN, Nieforth LO. Can Pets Prevent Suicide? The Impact of Companion Animals on Suicidality: Scoping Review and Clinical Recommendations. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233067

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Buiten, Hannah, Christy Turner, Jaci Gandenberger, Jenni Forkin, Ashley Taeckens, Kevin N. Morris, and Leanne O. Nieforth. 2025. "Can Pets Prevent Suicide? The Impact of Companion Animals on Suicidality: Scoping Review and Clinical Recommendations" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233067

APA StyleVan Buiten, H., Turner, C., Gandenberger, J., Forkin, J., Taeckens, A., Morris, K. N., & Nieforth, L. O. (2025). Can Pets Prevent Suicide? The Impact of Companion Animals on Suicidality: Scoping Review and Clinical Recommendations. Healthcare, 13(23), 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233067