Changes in Health Facility Readiness for Providing Quality Maternal and Newborn Care After Implementing the Safer Births Bundle of Care Package in Five Regions of Tanzania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Variables

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEmONC | Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care |

| CQI | Continuous Quality Improvement |

| PDSA | Plan, Do, Study, Act |

| SBBC | Safer Births Bundle of Care |

| PPROM | Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, J.P.; Day, L.T.; Rezende-Gomes, A.C.; Zhang, J.; Mori, R.; Baguiya, A.; Jayaratne, K.; Osoti, A.; Vogel, J.P.; Campbell, O.; et al. A Global Analysis of the Determinants of Maternal Health and Transitions in Maternal Mortality. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e306–e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000 to 2020: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and UNDESA/Population Division; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA; UNDESA/Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. World Health Statistics 2025: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality Report; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS-MIS); National Bureau of Statistics: Dodoma, Tanzania; Rockville, MD, USA, 2023.

- National Bureau of Statistics. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey 2022 Key Indicators Report; National Bureau of Statistics: Dodoma, Tanzania; Rockville, MD, USA, 2023.

- World Health Organization. Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA): An Annual Monitoring System for Service Delivery-Implementation Guide; Version 2.2; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ashish, K.; Raman, D.; Madan, S.; Upadhyaya, K.; Sundar, S. Quality of Care for Maternal and Newborn Health in Health Facilities in Nepal. Matern. Child Health J. 2020, 24 (Suppl. S1), 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, V.B.; Walker, N.; Kanyangarara, M. Estimating the Global Impact of Poor Quality of Care on Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes in 81 Low- And Middle-Income Countries: A Modeling Study. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livet, M.; Blanchard, C.; Richard, C. Readiness as a Precursor of Early Implementation Outcomes: An Exploratory Study in Specialty Clinics. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2022, 3, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamala, B.A.; Ersdal, H.L.; Mduma, E.; Moshiro, R.; Girnary, S.; Østrem, O.T.; Linde, J.; Dalen, I.; Søyland, E.; Bishanga, D.R.; et al. SaferBirths Bundle of Care Protocol: A Stepped-Wedge Cluster Implementation Project in 30 Public Health-Facilities in Five Regions, Tanzania. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamala, B.A.; Ersdal, H.L.; Moshiro, R.D.; Guga, G.; Dalen, I.; Kvaløy, J.T.; Bundala, F.A.; Makuwani, A.; Kapologwe, N.A.; Mfaume, R.S.; et al. Outcomes of a Program to Reduce Birth-Related Mortality in Tanzania. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersdal, H.; Mdoe, P.; Mduma, E.; Moshiro, R.; Guga, G.; Kvaløy, J.T.; Bundala, F.; Marwa, B.; Kamala, B. “Safer Births Bundle of Care” Implementation and Perinatal Impact at 30 Hospitals in Tanzania—Halfway Evaluation. Children 2023, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mduma, E.; Ersdal, H.; Svensen, E.; Kidanto, H.; Auestad, B.; Perlman, J. Frequent Brief On-Site Simulation Training and Reduction in 24-h Neonatal Mortality—An Educational Intervention Study. Resuscitation 2015, 93, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Monitoring Emergency Obstetric Care; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA): An Annual Monitoring System for Service Delivery-Reference Manual, Version 2.2; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Juma, D.; Stordal, K.; Kamala, B.; Bishanga, D.R.; Kalolo, A.; Moshiro, R. Readiness to Provide Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care: A Cross-Sectional Study in 30 Health Facilities in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. National Human Resource for Health Strategy 2021–2026; Ministy of Health: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2021.

- Kapologwe, N.A.; Meara, J.G.; Kengia, J.T.; Sonda, Y.; Gwajima, D.; Alidina, S.; Kalolo, A. Development and Upgrading of Public Primary Healthcare Facilities with Essential Surgical Services Infrastructure: A Strategy towards Achieving Universal Health Coverage in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Tanzania Service Availability and Readiness Assessment Report; Ministry of Health: Da es Salaam, Tanzania, 2021.

- Ministry of Health. Tanzania Service Availability and Readiness Assessment; Ministry of Health: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2024.

- Taylor, M.J.; McNicholas, C.; Nicolay, C.; Darzi, A.; Bell, D.; Reed, J.E. Systematic Review of the Application of the Plan-Do-Study-Act Method to Improve Quality in Healthcare. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2014, 23, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyte, L.; Sjursen, I.; Kleiven, O.T. The Impact of Pre-Round Meetings on Quality of Care: A Qualitative Study. Nurs. Open 2020, 7, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.E.; Stephani, A.M.; Sapple, P.; Clegg, A.J. The Effectiveness of Continuous Quality Improvement for Developing Professional Practice and Improving Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, M.; Puxty, A.; Miles, B. Making Quality Improvement Happen in the Real World: Building Capability and Improving Multiple Projects at the Same Time. BMJ Qual. Improv. Rep. 2016, 5, u207660.w4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, F.L.; Pembe, A.B.; Campbell, O.; Hanson, C.; Tripathi, V.; Wong, K.L.M.; Radovich, E.; Benova, L. Caesarean Section Provision and Readiness in Tanzania: Analysis of Crosssectional Surveys of Women and Health Facilities over Time. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e024216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, H.H.; Spiegelman, D.; Zhoub, X.; Kruka, M.E. Service Readiness of Health Facilities in Bangladesh, Haiti, Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, Nepal, Rwanda, Senegal, Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabene, S.M.; Orchard, C.; Howard, J.M.; Soriano, M.A.; Leduc, R. The Importance of Human Resources Management in Health Care: A Global Context. Hum. Resour. Health 2006, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalolo, A.; Gautier, L.; Radermacher, R.; Srivastava, S.; Meshack, M.; De Allegri, M. Factors Influencing Variation in Implementation Outcomes of the Redesigned Community Health Fund in the Dodoma Region of Tanzania: A Mixed-Methods Study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Benchmarks for Strengthening Health Emergency Capacities; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mold, J.W.; Hamm, R.M.; Mccarthy, L.H. The Law of Diminishing Returns in Clinical Medicine: How Much Risk Reduction Is Enough? J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2010, 23, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Tanzania Human Resource for Health Profile; Ministry of Health: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2023.

- Boniol, M.; Kunjumen, T.; Nair, T.S.; Siyam, A.; Campbell, J.; Diallo, K. The Global Health Workforce Stock and Distribution in 2020 and 2030: A Threat to Equity and ‘Universal’ Health Coverage? BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e009316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, G.; Eccles, M.; Grol, R.; Griffiths, C.; Grimshaw, J.; Grimshaw, J. Using Clinical Guidelines. BMJ 1999, 318, 728–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, V.C.; Silva, S.N.; Carvalho, V.K.S.; Zanghelini, F.; Barreto, J.O.M. Strategies for the Implementation of Clinical Practice Guidelines in Public Health: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2022, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Republic of Tanzania. National Guideline for Neonatal Care and Establishment of Neonatal Care Unit; United Republic of Tanzania: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2019; pp. 116–117. [Google Scholar]

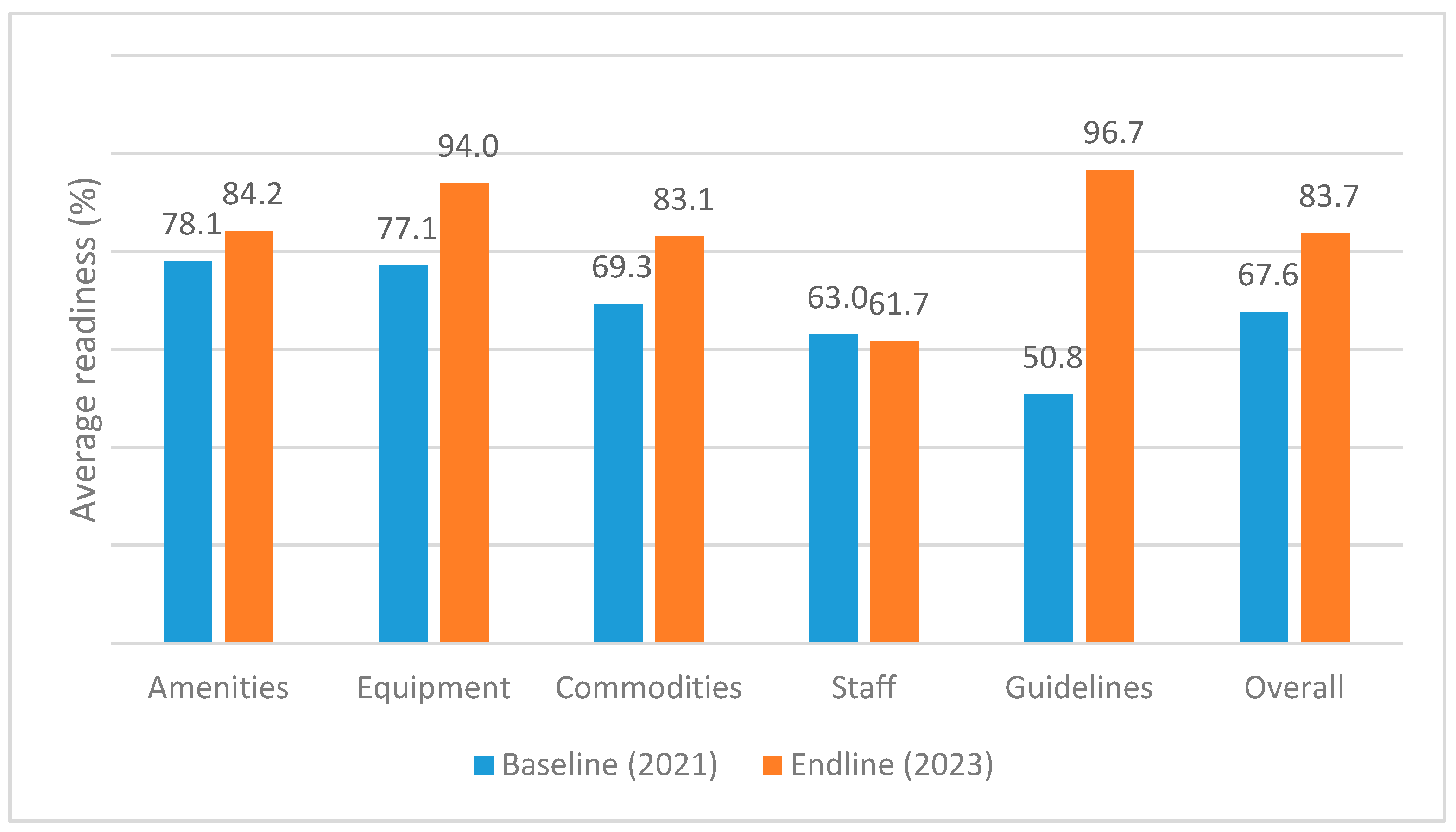

| Readiness | Baseline N = 28 | Endline N = 28 | Difference 1 | 95% CI 1,2 | p-Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Facility Readiness | |||||

| Amenity | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 78.1 (14.3) | 84.2 (9.0) | 6.1 | −0.29, 13 | 0.056 |

| Staffing | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 63.0 (16.6) | 61.7 (17.5) | −1.3 | −8.5, 5.9 | 0.714 |

| Basic equipment | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 77.1 (11.5) | 94.0 (6.4) | 16.9 | 12.1, 21.7 | 0.000 † |

| Commodities | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 69.3 (19.8) | 82.1 (14.1) | 12.9 | 6.3, 19.4 | 0.000 † |

| Guidelines | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 50.8 (20.9) | 96.7 (9.2) | 45.9 | 36.5, 55.3 | 0.000 † |

| Overall Readiness | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 67.6 (10.8) | 83.7 (6.3) | 16.1 | 10.7, 17.2 | 0.000 † |

| Regional Referral Hospital | District Hospital | Health Centre | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readiness | Baseline, N = 4 | Endline, N = 4 | Baseline, N = 14 | Endline, N = 14 | Baseline, N = 10 | Endline, N = 10 |

| Amenity | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 71.4 (11.7) | 75.0 (0.0) | 81.6 (11.8) * | 74.1 (3.3) * | 75.7 (17.9) | 72.5 (12.9) |

| Staffing | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 70.5 (23.9) | 65.9 (15.5) | 66.2 (12.1) | 68.2 (18.4) | 55.5 (17.9) | 50.9 (12.3) |

| Basic equipment | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 85.0 (11.4) | 98.3 (3.3) | 78.1 (10.6) *,† | 96.7 (3.5) *,† | 72.7 (11.9) * | 88.7 (7.1) * |

| Commodities | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 77.5 (18.9) | 84.1 (8.7) | 69.3 (14.9) *,† | 87.0 (8.5) *,† | 66.0 (26.3) | 74.5 (19.1) |

| Guidelines | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 67.9 (14.9) * | 100.0 (0.0) * | 53.1 (21.8) *,† | 95.4 (11.8) *,† | 40.7 (17.2) *,† | 97.1 (6.9) *,† |

| Overall Readiness | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 74.5 (14.6) | 84.7 (4.6) | 69.7 (5.6) *,† | 84.3 (5.6) *,† | 62.1 (13.1) *,† | 76.8 (5.1) *,† |

| Characteristic | Overall N = 28 1 | Regional Referral Hospital N = 4 1 | District Hospital N = 14 1 | Health Centre N = 10 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Grid electricity | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Solar | 4 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.02 |

| Generator | 27 (96.4) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 9 (90.0) | 0.5 |

| Solar or Generator | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Water on the visiting day | 26 (92.9) | 4 (100.0) | 13 (92.9) | 9 (90.0) | >0.9 |

| Emergency transportation | 26 (92.9) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 8 (80.0) | 0.2 |

| Fuel for ambulance | 26 (92.9) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 8 (80.0%) | 0.2 |

| Average readiness score | >0.9 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 84.2 (9.0) | 85.7 (0.0) | 84.7 (3.8) | 82.9 (14.8) | 0.89 # |

| Characteristic | Overall N = 28 1 | Regional Referral Hospital N = 4 1 | District Hospital N = 14 1 | Health Centre N = 10 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatrician | 4 (14.3) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.005 † |

| Gynecologist | 4 (14.3) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.005 † |

| Medical doctor | 26 (92.9) | 3 (75.0) | 14 (100.0) | 9 (90.0) | 0.12 |

| Assistant Medical Officer € | 18 (64.3) | 2 (50.0) | 11 (78.6) | 5 (50.0) | 0.3 |

| Clinical Officer α | 17 (60.7) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (71.4) | 7 (70.0) | 0.040 |

| Assistant Clinical Officer ¶ | 9 (32.1) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (50.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.13 |

| Nurse Officer § | 19 (67.9) | 4 (100.0) | 12 (85.7) | 3 (30.0) | 0.007 |

| Assistant Nurse Officer ¥ | 27 (96.4) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 9 (90.0) | 0.5 |

| Enrolled Nurse φ | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Health Information personnel | ¢ 12 (42.9) | 2 (50.0) | 8 (57.1) | 2 (20.0) | 0.2 |

| Anesthetist | 26 (92.9) | 4 (100.0) | 13 (92.9) | 9 (90.0) | >0.9 |

| Average Score | 61.7 | 65.9 | 68.2 | 50.9 | 0.089 # |

| Characteristic | Overall N = 28 1 | Regional Referral Hospital N = 4 1 | District Hospital N = 14 1 | Health Centre N = 10 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighing scale | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Thermometer (room) | 25 (89.3) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 7 (70.0) | 0.082 |

| Wall clock | 25 (89.3) | 3 (75.0) | 13 (92.9) | 9 (90.0) | 0.5 |

| Cesarian section set | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Vacuum extractor | 20 (71.4) | 4 (100.0) | 9 (64.3) | 7 (70.0) | 0.5 |

| Resuscitation space next to the delivery bed | 27 (96.4) | 4 (100.0) | 13 (92.9) | 10 (100.0) | >0.9 |

| Newborn Suction next to the delivery bed | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Newborn Bag/mask next to the delivery bed | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Penguin sucker | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Mask size 0 | 27 (96.4) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 9 (90.0) | 0.5 |

| Mask size 1 | 26 (92.9) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 8 (80.0) | 0.2 |

| Radiant warmer | 26 (92.9) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 8 (80.0) | 0.2 |

| Oxygen cylinder/flow metre, humidifier | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Small oxygen cylinder for transport | 25 (89.3) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 7 (70.0) | 0.082 |

| Oxygen concentrator | 26 (92.9) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 8 (80.0) | 0.2 |

| Average score | 94.0 | 98.3 | 96.7 | 88.7 | 0.0094 # |

| Characteristic | Overall N = 28 1 | Regional Referral Hospital N = 4 1 | District Hospital N = 14 1 | Health Centre N = 10 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobinometer | 18 (64.3) | 2 (50.0) | 10 (71.4) | 6 (60.0) | 0.7 |

| Glucose metre | 23 (82.1) | 3 (75.0) | 12 (85.7) | 8 (80.0) | >0.9 |

| Dextrose 10% | 25 (89.3) | 4 (100.0) | 13 (92.9) | 8 (80.0) | 0.7 |

| Normal saline | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Vitamin K | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Ampicillin/gentamicin | 26 (92.9) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 8 (80.0) | 0.2 |

| Adrenaline injection | 25 (89.3) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 7 (70.0) | 0.082 |

| Phenobarbital injection | 21 (75.0) | 4 (100.0) | 12 (85.7) | 5 (50.0) | 0.11 |

| Magnesium Sulphate | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Safe blood 24 hrs | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Blood out of stock in 90 days before the study | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (21.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4 |

| Average score | 82.1 | 84.1 | 87.0 | 74.5 | 0.082 # |

| Characteristic | Overall N = 28 1 | Regional Referral Hospital N = 4 1 | District Hospital N = 14 1 | Health Centre N = 10 1 | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National neonatal guidelines | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Essential newborn care guidelines | 27 (96.4) | 4 (100.0) | 13 (92.9) | 10 (100.0) | >0.9 |

| Standard operating procedure set | 26 (92.9) | 4 (100.0) | 12 (85.7) | 10 (100.0) | 0.6 |

| Newborn triage checklist | 25 (89.3) | 4 (100.0) | 12 (85.7) | 9 (90.0) | >0.9 |

| Discharge feedback form | 25 (89.3) | 4 (100.0) | 13 (92.9) | 8 (80.0) | 0.7 |

| Referral form | 27 (96.4) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 9 (90.0) | 0.5 |

| HBB poster | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Prolonged labour | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Pre-eclampsia | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 27 (96.4) | 4 (100.0) | 13 (92.9) | 10 (100.0) | >0.9 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Abnormal fetal heart rate | 27 (96.4) | 4 (100.0) | 13 (92.9) | 10 (100.0) | >0.9 |

| PPROM | 27 (96.4) | 4 (100.0) | 13 (92.9) | 10 (100.0) | >0.9 |

| Antenatal Corticosteroid | 28 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 14 (100.0) | 10 (100.0) | |

| Average readiness | 96.7 | 100.0 | 95.4 | 97.1 | 0.6069 # |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juma, D.; Stordal, K.; Kamala, B.; Bishanga, D.R.; Kalolo, A.; Moshiro, R.; Kvaløy, J.T.; Guga, G.; Manongi, R. Changes in Health Facility Readiness for Providing Quality Maternal and Newborn Care After Implementing the Safer Births Bundle of Care Package in Five Regions of Tanzania. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3060. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233060

Juma D, Stordal K, Kamala B, Bishanga DR, Kalolo A, Moshiro R, Kvaløy JT, Guga G, Manongi R. Changes in Health Facility Readiness for Providing Quality Maternal and Newborn Care After Implementing the Safer Births Bundle of Care Package in Five Regions of Tanzania. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3060. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233060

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuma, Damas, Ketil Stordal, Benjamin Kamala, Dunstan R. Bishanga, Albino Kalolo, Robert Moshiro, Jan Terje Kvaløy, Godfrey Guga, and Rachel Manongi. 2025. "Changes in Health Facility Readiness for Providing Quality Maternal and Newborn Care After Implementing the Safer Births Bundle of Care Package in Five Regions of Tanzania" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3060. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233060

APA StyleJuma, D., Stordal, K., Kamala, B., Bishanga, D. R., Kalolo, A., Moshiro, R., Kvaløy, J. T., Guga, G., & Manongi, R. (2025). Changes in Health Facility Readiness for Providing Quality Maternal and Newborn Care After Implementing the Safer Births Bundle of Care Package in Five Regions of Tanzania. Healthcare, 13(23), 3060. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233060

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)