The Moderating Role of Personality on the Effects of Concentration-, Ethics- and Wisdom-Based Meditation Practices for Well-Being and Prosociality

Highlights

- Individuals high in neuroticism showed greater prosocial gains when mindfulness interventions included both ethics- and wisdom-based meditation practices.

- Incorporating wisdom-based practices alongside traditional ethics-based components may enhance the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions for certain personality profiles.

- Tailoring mindfulness interventions according to personality traits may improve their impact in both clinical and non-clinical contexts.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Hypotheses

1.1.1. Openness to Experiences

1.1.2. Conscientiousness Hypothesis

1.1.3. Extraversion Hypothesis

1.1.4. Agreeableness Hypothesis

1.1.5. Neuroticism Hypothesis

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Intervention Design

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Ten-Item Personality Inventory

2.3.2. Ryff’s Brief Scale of Psychological Well-Being

2.3.3. Prosocialness Scale for Adults

2.3.4. Intervention Delivery Checks

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Moderation Effects

3.3. Personality Trait Moderation of Prosocialness

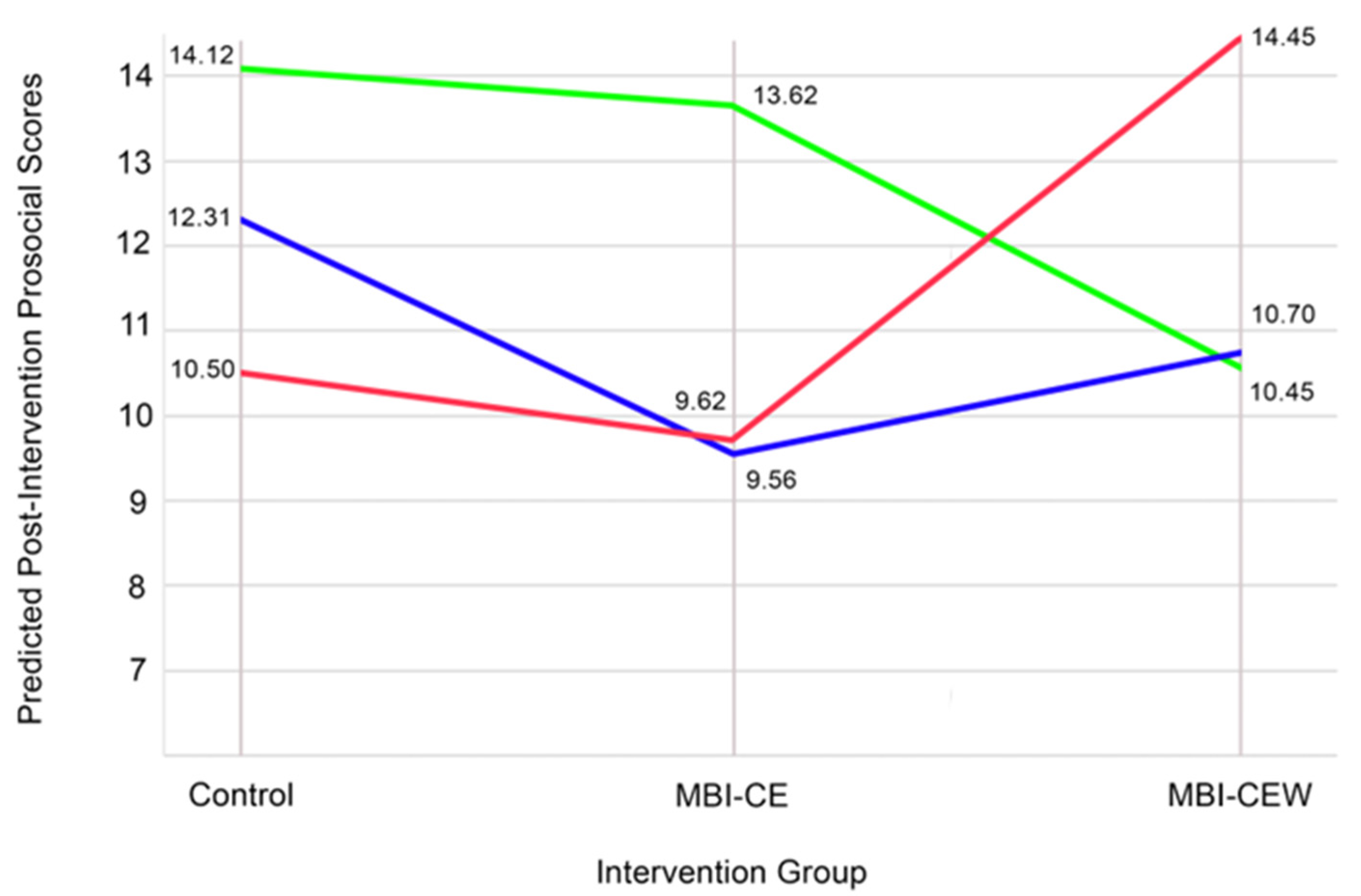

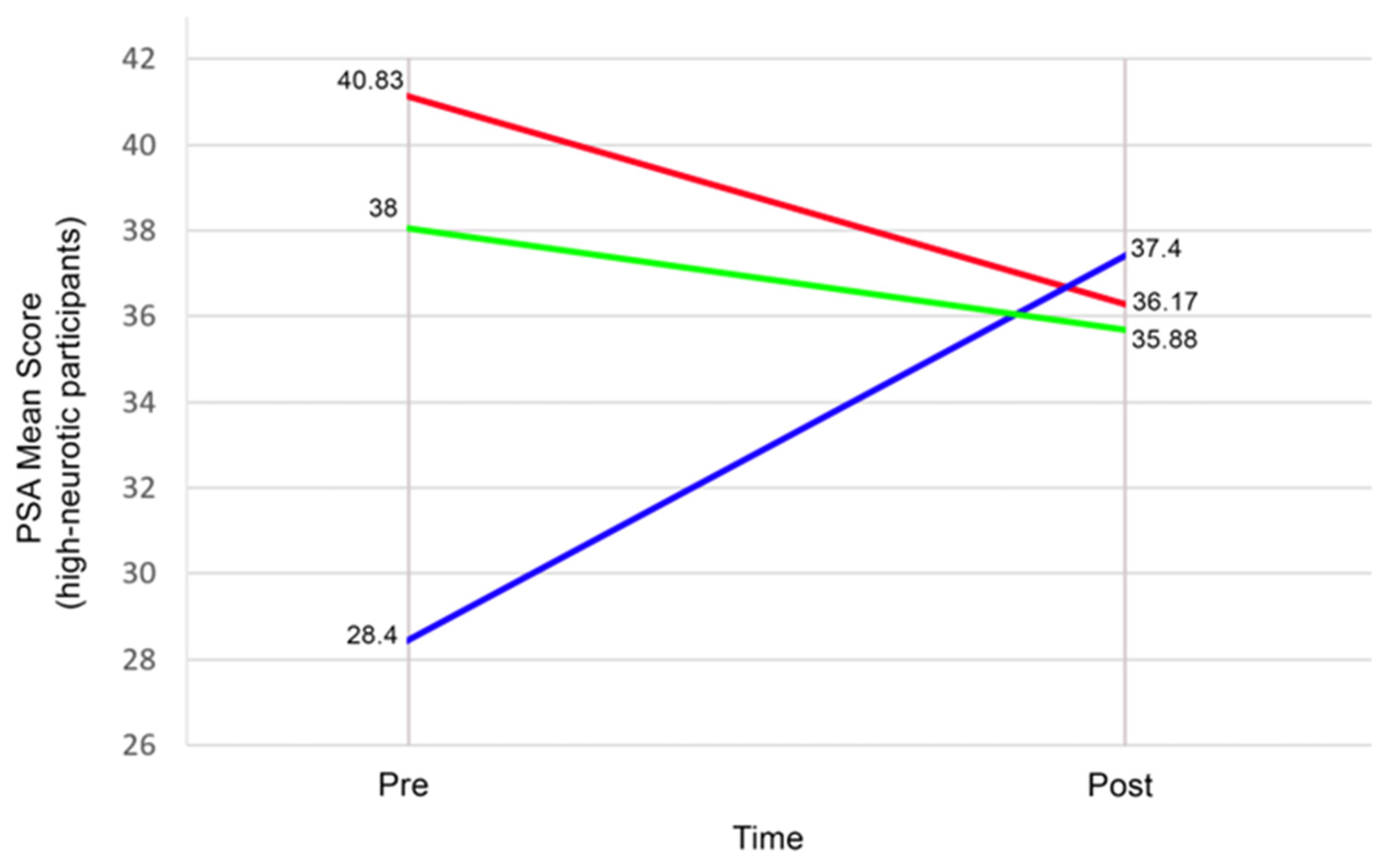

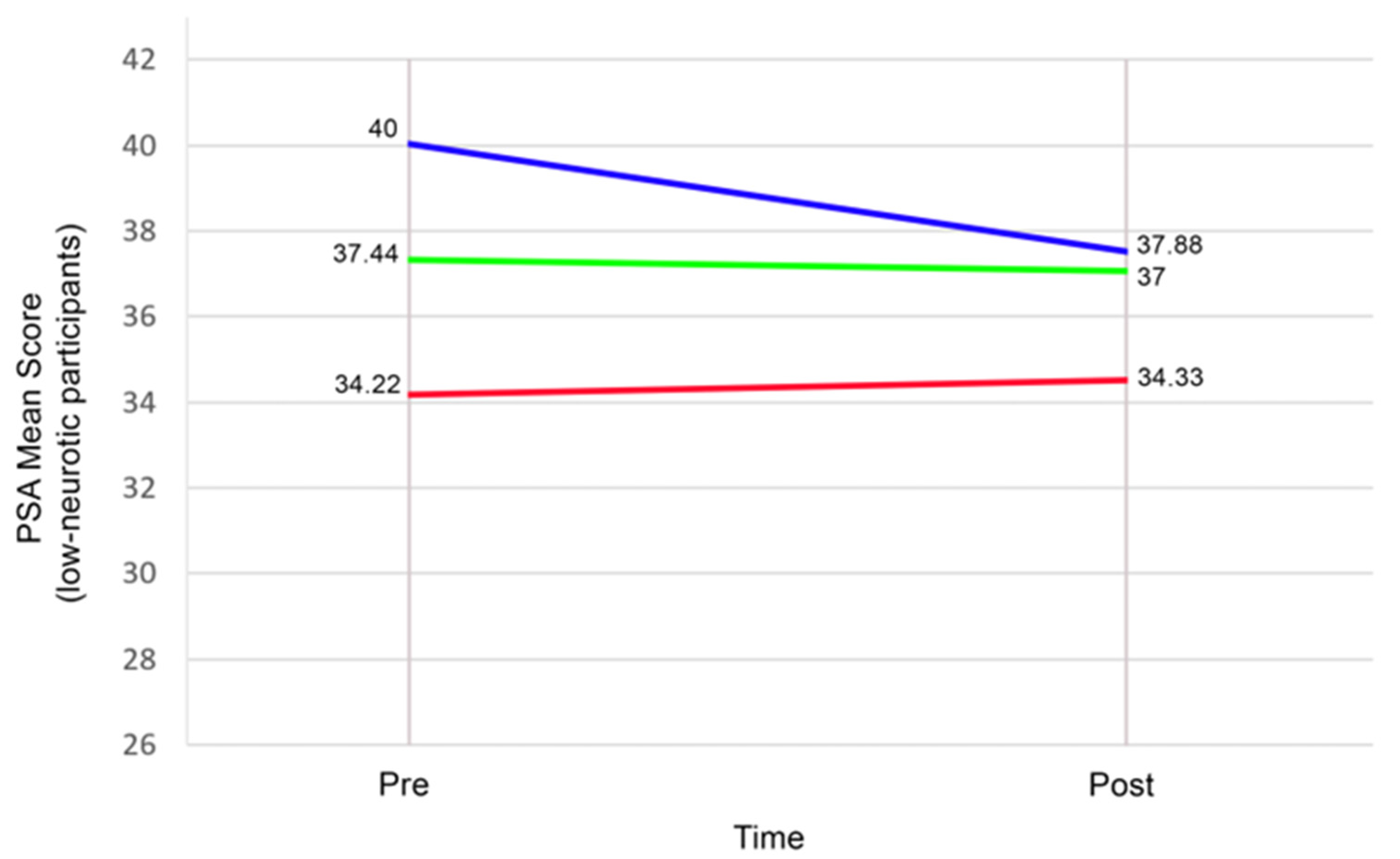

3.3.1. Neuroticism

3.3.2. Agreeableness

3.3.3. Conscientiousness

3.3.4. Openness

3.3.5. Extraversion

3.4. Personality Trait Moderation of Well-Being

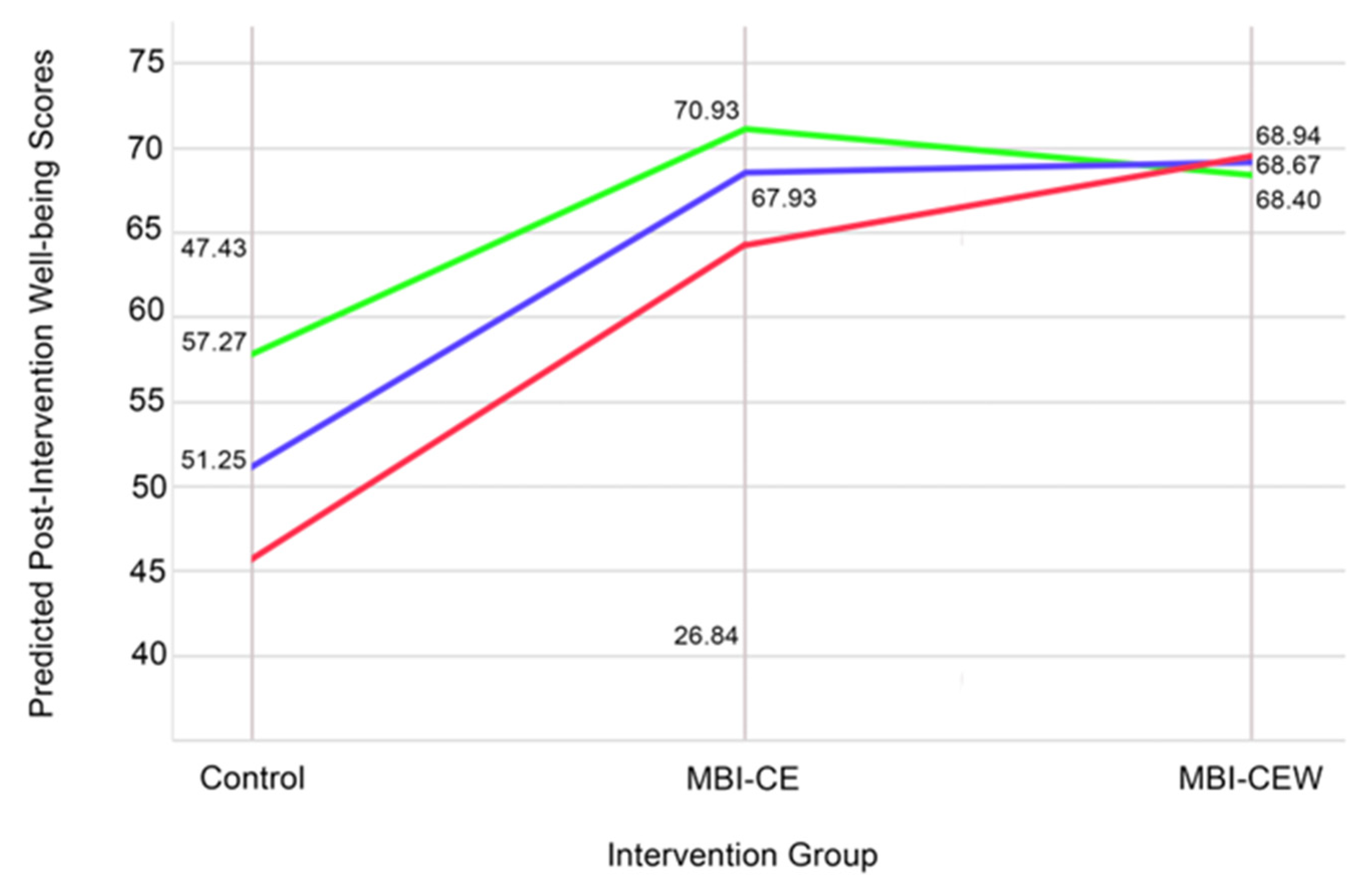

3.4.1. Neuroticism

3.4.2. Agreeableness

3.4.3. Conscientiousness

3.4.4. Openness

3.4.5. Extraversion

3.5. Intervention Delivery Checks

4. Discussion

4.1. Hypothesis 1: Openness to Experience

4.2. Hypothesis 2: Conscientiousness

4.3. Hypothesis 3: Extraversion

4.4. Hypothesis 4: Agreeableness

4.5. Hypothesis 5: Neuroticism

4.6. Ethics and/or Wisdom-Based Meditations

4.7. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MBI-CE | Mindfulness-Based Intervention including Concentration and Ethics-based meditation practices |

| MBI-CEW | Mindfulness-Based Intervention including Concentration, Ethics-, and Wisdom-based meditation practices |

| PSA | The Prosocialness Scale for Adults |

| PWB | Ryff’s Brief Scale of Psychological Well-being |

References

- Tang, R.; Braver, T.S. Towards an individual differences perspective in mindfulness Training Research: Theoretical and Empirical Considerations. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K.; Judge, T.A. Personality and performance at the beginning of the new millennium: What do we know and where do we go next? Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2001, 9, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, J.T.; Randall, J.G. A meta-analysis of trait mindfulness: Relationships with the big five personality traits, intelligence, and anxiety. J. Res. Personal. 2022, 101, 104307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giluk, T.L. Mindfulness, Big Five personality, and affect: A meta-analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, A.W.; Garland, E.L. The Mindful Personality: A Meta-analysis from a Cybernetic Perspective. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1456–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Den Hurk, P.A.M.; Wingens, T.; Giommi, F.; Barendregt, H.P.; Speckens, A.E.M.; Van Schie, H.T. On the Relationship Between the Practice of Mindfulness Meditation and Personality—An Exploratory Analysis of the Mediating Role of Mindfulness Skills. Mindfulness 2011, 2, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.L.; Waltz, J. Everyday mindfulness and mindfulness meditation: Overlapping constructs or not? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 43, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T.; Hopkins, J.; Krietemeyer, J.; Toney, L. Five facet mindfulness questionnaire. In PsycTESTS Dataset; APA PsychNet: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnell, M.; Van Gordon, W.; Elander, J. Calmer, Kinder, Wiser: A Novel Threefold Categorization for Mindfulness-Based Interventions. Mindfulness 2023, 15, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, E.C.; Deković, M.; Van Londen, M.; Reitz, E. Personality as a moderator of intervention effects: Examining differential susceptibility. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 186, 111323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Íñiguez, R.; Montero, A.C.; Burgos-Julián, F.A.; Roche, J.R.F.; Santed, M.A. Interactions between Personality and Types of Mindfulness Practice in Reducing Burnout in Mental Health Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucher, M.A.; Suzuki, T.; Samuel, D.B. A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 70, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoro, C.I.; Galvez-Sánchez, C.M. Personality, Intervention and Psychological Treatment: Untangling and explaining new horizons and perspectives. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saggino, A.; Bartoccini, A.; Sergi, M.R.; Romanelli, R.; Macchia, A.; Tommasi, M. Assessing Mindfulness on Samples of Italian Children and Adolescents: The Validation of the Italian Version of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1364–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krick, A.; Felfe, J. Who benefits from mindfulness? The moderating role of personality and social norms for the effectiveness on psychological and physiological outcomes among police officers. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vibe, M.; Solhaug, I.; Tyssen, R.; Friborg, O.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Sørlie, T.; Halland, E.; Bjørndal, A. Does Personality moderate the effects of mindfulness training for medical and psychology students? Mindfulness 2013, 6, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winning, A.P.; Boag, S. Does brief mindfulness training increase empathy? The role of personality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 86, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gordon, W.; Shonin, E. Second-Generation Mindfulness-Based Interventions: Toward more authentic mindfulness practice and teaching. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnell, M.; Van Gordon, W.; Elander, J. A comparison of the effects of Ethics- versus Wisdom-Based mindfulness practices on prosocial behaviour. Mindfulness 2024, 16, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Braver, T.S. Predicting Individual Preferences in Mindfulness Techniques Using Personality Traits. Front Psychol. 2020, 11, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barkan, T.; Hoerger, M.; Gallegos, A.M.; Turiano, N.A.; Duberstein, P.R.; Moynihan, J.A. Personality predicts utilization of Mindfulness-Based stress reduction during and Post-Intervention in a community sample of older adults. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2016, 22, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Jordan, C.H. Incorporating ethics into brief mindfulness practice: Effects on well-being and prosocial behavior. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purser, R.E. Clearing the Muddled Path of Traditional and Contemporary Mindfulness: A Response to Monteiro, Musten, and Compson. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compson, J.F. Is mindfulness secular or religious, and does it matter? In Practitioner’s Guide to Ethics and Mindfulness-Based Interventions. Mindfulness in Behavioral Health; Monteiro, L., Compson, J., Musten, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braarvig, J. Ideas on universal ethics in Mahāyāna Buddhism. Diogenes 2017, 64, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; Lejuez, C.; Krueger, R.F.; Richards, J.M.; Hill, P.L. What is conscientiousness and how can it be assessed? Dev. Psychol. 2012, 50, 1315–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; LePine, J.A.; Noe, R.A. Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: A meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 678–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. The NEO Personality Inventory Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Wiese, D.; Vaidya, J.; Tellegen, A. The two general activation systems of affect: Structural findings, evolutionary considerations, and psychobiological evidence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 820–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, P.; Van Gordon, W. Ontological Addiction Theory and Mindfulness-Based Approaches in the context of Addiction Theory and Treatment. Religions 2021, 12, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, W.G.; Habashi, M.M.; Sheese, B.E.; Tobin, R.M. Agreeableness, empathy, and helping: A person × situation perspective. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.; Woollacott, M. Effects of level of meditation experience on attentional focus: Is the efficiency of executive or orientation networks improved? J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2007, 13, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, A.P.; Stanley, E.A.; Kiyonaga, A.; Wong, L.; Gelfand, L. Examining the protective effects of mindfulness training on working memory capacity and affective experience. Emotion 2010, 10, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widiger, T.A.; Oltmanns, J.R. Neuroticism is a fundamental domain of personality with enormous public health implications. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Four ways five factors are basic. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1992, 13, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyklíček, I.; Irrmischer, M. For whom does Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction work? Moderating Effects of Personality. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.D.; Lynam, D.R.; Vize, C.; Crowe, M.; Sleep, C.; Maples-Keller, J.L.; Few, L.R.; Campbell, W.K. Vulnerable narcissism is (Mostly) a disorder of neuroticism. J. Personal. 2017, 86, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.; Hadash, Y.; Lichtash, Y.; Tanay, G.; Shepherd, K.; Fresco, D.M. Decentering and related constructs. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gordon, W.; Shonin, E.; Sumich, A.; Sundin, E.C.; Griffiths, M.D. Meditation Awareness Training (MAT) for Psychological Well-Being in a Sub-Clinical Sample of University Students: A controlled pilot study. Mindfulness 2014, 5, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J. Res. Personal. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thørrisen, M.M.; Sadeghi, T. The Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI): A scoping review of versions, translations and psychometric properties. Front Psychol. 2023, 14, 1202953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Best news yet on the six-factor model of well-being. Soc. Sci. Res. 2006, 35, 1103–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Steca, P.; Zelli, A.; Capanna, C. A new scale for measuring adults’ prosocialness. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2005, 21, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røvik, J.O.; Tyssen, R.; Gude, T.; Moum, T.; Ekeberg, Ø.; Vaglum, P. Exploring the interplay between personality dimensions: A comparison of the typological and the dimensional approach in stress research. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 42, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.M.; Hagen, A.; Mobach, L.; Zimmermann, R.; Baartmans, J.M.D.; Rahemenia, J.; De Gier, E.; Schneider, S.; Ollendick, T.H. The importance of Practicing at Home during and following Cognitive Behavioral therapy for Childhood Anxiety Disorders: A conceptual review and New directions to Enhance homework using MHealth Technology. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 27, 602–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, C.J.; Lutz, A.; Davidson, R.J. Reconstructing and deconstructing the self: Cognitive mechanisms in meditation practice. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, L.A.; Dovidio, J.F.; Piliavin, J.A.; Schroeder, D.A. Prosocial Behavior: Multilevel perspectives. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 56, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 38, 668–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, R.A.; Diener, E. Personality correlates of subjective Well-Being. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 11, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A. On traits and temperament: General and specific factors of emotional experience and their relation to the Five-Factor model. J. Personal. 1992, 60, 441–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edershile, E.A.; Wright, A.G. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissistic states in interpersonal situations. Self Identity 2019, 20, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzberg, S. Lovingkindness: The Revolutionary Art of Happiness; Shambhala: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bankard, J. Training Emotion cultivates morality: How Loving-Kindness Meditation hones compassion and increases prosocial behavior. J. Relig. Health 2015, 54, 2324–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Grossman, P.; Hinton, D.E. Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: Potential for psychological interventions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valor, C.; Martínez-De-Ibarreta, C.; Carrero, I.; Merino, A. Effects of loving-kindness meditation on prosocial behavior: Empirical and meta-analytic evidence. J. Soc. Mark. 2024, 14, 280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gordon, W.; Shonin, E.; Dunn, T.J.; Sapthiang, S.; Kotera, Y.; Garcia-Campayo, J.; Sheffield, D. Exploring Emptiness and its Effects on Non-attachment, Mystical Experiences, and Psycho-spiritual Wellbeing: A Quantitative and Qualitative Study of Advanced Meditators. EXPLORE 2019, 15, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furnell, M.; Van Gordon, W.; Elander, J. Wisdom-Based Buddhist-Derived Meditation Practices for Prosocial Behaviour: A Systematic Review. Mindfulness 2024, 15, 539–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Chandwani, R.; Navare, A. How can mindfulness enhance moral reasoning? An examination using business school students. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2018, 27, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y. Examining interpersonal self-transcendence as a potential mechanism linking meditation and social outcomes. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S.; Milne, G.R.; Ross, S.M.; Mick, D.G.; Grier, S.A.; Chugani, S.K.; Chan, S.S.; Gould, S.; Cho, Y.-N.; Dorsey, J.D.; et al. Mindfulness: Its transformative potential for consumer, societal, and environmental well-being. J. Public Policy Mark. 2016, 35, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safran, J.D. Psychoanalysis and Buddhism: An Unfolding Dialogue; Wisdom Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yaden, D.B.; Haidt, J.; Hood, R.W.; Vago, D.R.; Newberg, A.B. The varieties of Self-Transcendent experience. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2017, 21, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josipovic, Z. Neural correlates of nondual awareness in meditation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2013, 1307, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, M.J.; Ministero, L.M.; Gabriel, S.; Morrison, C.D.; Naidu, E. Minding your own business? Mindfulness decreases prosocial behavior for people with independent self-construals. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 32, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalai, L.a.m.a.; Chodron, T. Higher training in wisdom: The role of mindfulness and introspective awareness. In The Library of Wisdom and Compassion: Following in the Buddha’s Footsteps; Lama, D., Chodron, T., Eds.; Wisdom Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, D.R.; Hoerr, J.P.; Cesko, S.; Alayoubi, A.; Carpio, K.; Zirzow, H.; Walters, W.; Scram, G.; Rodriguez, K.; Beaver, V. Does mindfulness training without explicit ethics-based instruction promote prosocial behaviors? A meta-analysis. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 46, 1247–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcome Measure | Group | Pre- | Post- | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Prosocialness Scale for Adults (PSA) | MBI-CE | 21 | 38.00 | 9.04 | 35.38 | 10.22 |

| MBI-CEW | 18 | 33.56 | 10.35 | 37.61 | 6.36 | |

| Control | 17 | 37.71 | 12.99 | 36.47 | 10.70 | |

| Ryff’s Brief Scale of Psychological Well-being (PWB) | MBI-CE | 21 | 68.76 | 6.11 | 71.29 | 5.01 |

| MBI-CEW | 18 | 68.67 | 6.88 | 71.78 | 5.02 | |

| Control | 17 | 36.12 | 13.04 | 39.53 | 12.06 | |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Sample Size (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism (Pre) | 7.96 | 3.29 | 2 | 14 | 56 |

| Agreeableness (Pre) | 9.80 | 2.54 | 6 | 14 | 56 |

| Conscientiousness (Pre) | 8.05 | 2.77 | 3 | 14 | 56 |

| Openness (Pre) | 7.70 | 2.38 | 2 | 13 | 56 |

| Extraversion (Pre) | 8.34 | 2.68 | 2 | 14 | 56 |

| Prosocial (Pre) | 36.48 | 10.77 | 19 | 62 | 56 |

| Prosocial (Post) | 36.43 | 9.20 | 17 | 58 | 56 |

| Well-being (Pre) | 58.82 | 17.51 | 19 | 79 | 56 |

| Well-being (Post) | 61.80 | 16.72 | 17 | 88 | 56 |

| Statistic | Neuroticism | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Openness | Extraversion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Explained (R2) | 0.578 | 0.536 | 0.595 | 0.549 | 0.549 |

| F-Statistic (F) | 11.17 | 9.44 | 12.00 | 9.92 | 9.95 |

| p-Value (F-Test) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Baseline Prosocial Scores (β) | 0.678 (p < 0.001) | 0.656 (p < 0.001) | 0.661 (p < 0.001) | 0.634, p < 0.001 | 0.653 (p < 0.001) |

| Intervention Group (MBI-CE) (β) | −6.71 (p = 0.317) | −1.33 (p = 0.545) | 10.46 (p = 0.101) | −10.41 (p = 0.455) | −4.59 (p = 0.450) |

| Intervention Group (MBI-CEW) (β) | −13.44 (p = 0.079) | 4.03 (p = 0.086) | −2.66 (p = 0.747) | −5.32 (p = 0.674) | 3.82 (p = 0.524) |

| Trait (β) | −0.68 (p = 0.240) | 0.814 (p = 0.614) | −0.084 (p = 0.896) | −0.28 (p = 0.783) | −0.48 (p = 0.312) |

| Interaction (MBI-CE × Trait) (β) | 0.70 (p = 0.372) | −0.879 (p = 0.675) | 1.15 (p = 0.132) | 0.89 (p = 0.481) | 0.34 (p = 0.623) |

| Interaction (MBI-CEW × Trait) (β) | 2.09 (p = 0.021) | 0.866 (p = 0.721) | 0.79 (p = 0.423) | 0.99 (p = 0.392) | −0.09 (p = 0.897) |

| Statistic | Neuroticism | Agreeableness | Conscientiousness | Openness | Extraversion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Explained (R2) | 0.852 | 0.854 | |||

| F-Statistic (F) | 46.98 | 47.93 | |||

| p-Value (F-Test) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Baseline Prosocial Scores (β) | 0.387 (p = 0.001) | 0.343 (p = 0.002) | (p | ||

| Intervention Group (MBI-CE) (β) | 7.521 (p = 0.343) | 6.401 (p = 0.403) | (p | ) | |

| Intervention Group (MBI-CEW) (β) | 6.751 (p = 0.446) | 0.879 (p = 0.919) | (p | ) | ) |

| Trait (β) | −1.648 (p = 0.010) | −1.775 (p = 0.012) | (p ) | ||

| Interaction (MBI-CE × Trait) (β) | 1.520 (p = 0.068) | 1.873 (p = 0.044) | (p ) | ||

| Interaction (MBI-CEW × Trait) (β) | 1.671 (p = 0.076) | 2.701 (p = 0.012) | (p ) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Furnell, M.; Van Gordon, W.; Elander, J. The Moderating Role of Personality on the Effects of Concentration-, Ethics- and Wisdom-Based Meditation Practices for Well-Being and Prosociality. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3044. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233044

Furnell M, Van Gordon W, Elander J. The Moderating Role of Personality on the Effects of Concentration-, Ethics- and Wisdom-Based Meditation Practices for Well-Being and Prosociality. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3044. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233044

Chicago/Turabian StyleFurnell, Matthew, William Van Gordon, and James Elander. 2025. "The Moderating Role of Personality on the Effects of Concentration-, Ethics- and Wisdom-Based Meditation Practices for Well-Being and Prosociality" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3044. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233044

APA StyleFurnell, M., Van Gordon, W., & Elander, J. (2025). The Moderating Role of Personality on the Effects of Concentration-, Ethics- and Wisdom-Based Meditation Practices for Well-Being and Prosociality. Healthcare, 13(23), 3044. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233044