Abstract

Background/Objectives: This study aimed to develop the Technological Competency as Caring in Healthcare Providers Instrument (TCCHI) for multidisciplinary use, based on Locsin’s theory of Technological Competency as Caring in Nursing. Methods: A content validation design employing a modified Delphi technique was conducted with a multidisciplinary panel of 10 healthcare experts (recruited by purposive sampling based on expertise in technology/caring). The preliminary 67-item pool was derived from a literature review and theoretical alignment. Two Delphi rounds were implemented to establish face and content validity. Qualitative feedback from Round 1 guided item refinement for Round 2. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used to confirm the response stability between rounds. Results: Among the 67 initial items, 38 were retained after two Delphi rounds, achieving an I-CVI of 0.80–0.90. Response stability was established (p > 0.05). The resulting 38 items were categorized into six refined concepts reflecting the integration of technology and caring. Inter-rater consistency, assessed by the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), was moderate (Round 1 ICC = 0.49; Round 2 ICC = 0.50), suggesting initial variability among the multidisciplinary panel. Conclusions: The TCCHI is a comprehensive and theoretically grounded instrument applicable across diverse healthcare disciplines. However, the moderate inter-rater consistency suggests that further empirical validation is required. Further psychometric evaluation, including confirmatory factor analysis and internal consistency reliability testing, is required to establish construct validity and strengthen the instrument’s applicability in diverse healthcare settings.

1. Introduction

The rapid evolution of healthcare technology, from electronic health records to artificial intelligence, offers unprecedented opportunities to improve patient outcomes and safety [1]. However, this technological integration also poses a significant challenge: how to ensure that technology enhances, rather than diminishes, the humanistic and compassionate core of healthcare.

This challenge is addressed by Locsin’s “Technological Competency as Caring in Nursing” (TCCN) theory, a middle-range nursing theory that emphasizes the harmonious coexistence of technology and caring [2]. The TCCN theory requires that technology be used with a strong ethical–moral compass to preserve and enhance patient dignity, ensuring that care is holistic and person-centered [3,4].

Various instruments have been developed to measure these constructs. These include general caring measures such as the Caring Behaviors Inventory (CBI) and the Caring Assessment Report Evaluation Q-sort (CARE-Q) [5,6,7] and TCCN-specific instruments such as the Technological Competency as Caring in Nursing Instrument (TCCNI) and its revisions (e.g., TCCNI-R, PITCCN) [8,9,10,11,12].

However, a significant limitation of these conventional instruments is their exclusive focus on nurses. They fail to reflect the complexity and diversity of modern healthcare, which increasingly relies on collaborative, interdisciplinary teams [13,14]. The absence of a standardized, multidisciplinary instrument means that the crucial intersection of technological competency and caring cannot be comprehensively measured across the entire healthcare profession. Caring competencies are required not only of nurses but of all healthcare professionals [15,16], for example, when a provider skillfully uses technology while maintaining empathy to address a patient’s anxiety.

Thus, the need for a robust, innovative instrument to assess technological competency among various healthcare professionals in high-tech settings is evident.

In this study, we aimed to develop and validate a new multidisciplinary Technological Competency as Caring in Healthcare Providers Instrument (TCCHI) for use across healthcare professions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework: Technological Competency as Caring in Healthcare

To bridge this gap and facilitate person-centered, compassionate care in high-tech, multi-disciplinary settings, we developed the Technological Competency as Caring in Healthcare Providers (TCCH) conceptual framework, extending Locsin’s theory for interprofessional use. This framework defines TCCH through six essential dimensions, reflecting a holistic approach in which technology is a tool for expressing genuine care and enhancing patient–provider relationships.

Based on a comprehensive literature review and Locsin’s TCCN theory, we developed a conceptual framework for TCCH. This framework outlines six essential dimensions that define TCCH for healthcare professionals, reflecting a holistic approach in which technology is a tool for expressing genuine care and enhancing patient–provider relationships.

In this context, “technology” refers to tools such as information and communication technology (ICT), artificial intelligence (AI), medical devices, and clinical systems used to understand and support patients [17].

“Care” refers to demonstrating compassion and respect in communication, building trust, and supporting patient growth and development [18,19]. Technological competency in patient care involves the ethical and skillful use of technology to understand and respect patients [3].

Concept 1. Promoting self-growth and technological learning: This concept focuses on the continuous professional development required for healthcare providers to ethically and effectively integrate technology into their practice. It involves cultivating awareness of one’s own capabilities and a willingness to learn from patients to expand knowledge and refine skills as a practitioner [20,21,22]. This growth is crucial for remaining competent, providing high-quality care, and adapting to new challenges in the field. It also requires understanding not only how a technology works, but also its capabilities, limitations, and ethical implications, such as data privacy and the risk of dehumanization [4,23]. A deep and critical understanding of technology ensures that its use achieves humanistic goals, such as improving workflow efficiency, enhancing diagnostic accuracy, and ultimately improving patient safety.

Concept 2. Building trust relationships with patients: This concept highlights the importance of fostering trusting relationships through the thoughtful application of technology [3]. It encapsulates the core principles of person-centered care and a holistic approach by prioritizing human connections and demonstrating empathy [24,25,26]. This approach emphasizes that the art of caring lies in understanding, respecting, and connecting with individual patients in their entirety to build effective therapeutic relationships.

Concept 3. Providing person-centered care through the appropriate use of technology: This concept involves placing patients at the center of all decisions and actions [27]. It goes beyond merely treating an illness to caring for the whole person and recognizing their unique values, preferences, needs, and goals [28,29]. This approach ensures that care is personalized, comprehensive, and compassionate, helping patients feel like partners in their own health journey. For example, considering a patient’s desire to return to work after surgery is as important as the surgical outcome itself.

Concept 4, Enhancing the physical and emotional comfort of patients: This concept focuses on relieving both physical and mental discomfort. Physical comfort refers to the absence of pain or distress [30], while emotional comfort is a state of psychological well-being in which an individual feels safe and supported [31]. Prioritizing both is fundamental to healing and should not be considered a luxury. When healthcare teams are well-trained in technology, they can work more efficiently and avoid errors, which reduces patient anxiety and enhances overall outcomes [32,33,34].

Concept 5, Promoting patient learning and growth: This concept emphasizes that healthcare involves facilitating the patient’s journey toward greater understanding, self-management and independence. This approach highlights the importance of using technology to support patient autonomy by coaching patients to manage their health rather than unilaterally delivering information. Without clear and accessible information, patients cannot provide informed consent or meaningfully participate in their care, which can lead to distrust and poor outcomes [35]. Respecting a patient’s self-determination fosters trust and a sense of control, which are vital for their psychological well-being and satisfaction with care [36,37].

Concept 6, Engaging in ethico-moral practice regarding technology use and patient advocacy: This concept emphasizes the ethical responsibility of healthcare professionals to use technology with a caring intent. It involves not only being proficient in technologies such as AI and telemedicine but also cultivating an ongoing awareness of the ethical issues they present, including data privacy, patient advocacy, and consent [38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. This concept also involves having the moral courage to speak on behalf of patients who cannot express their wishes and maintaining professional accountability by addressing inappropriate behavior among colleagues [45,46,47]. It requires a profound commitment to ethical sensitivity and recognition of each patient as a unique and invaluable individual.

2.2. Study Design and Phases

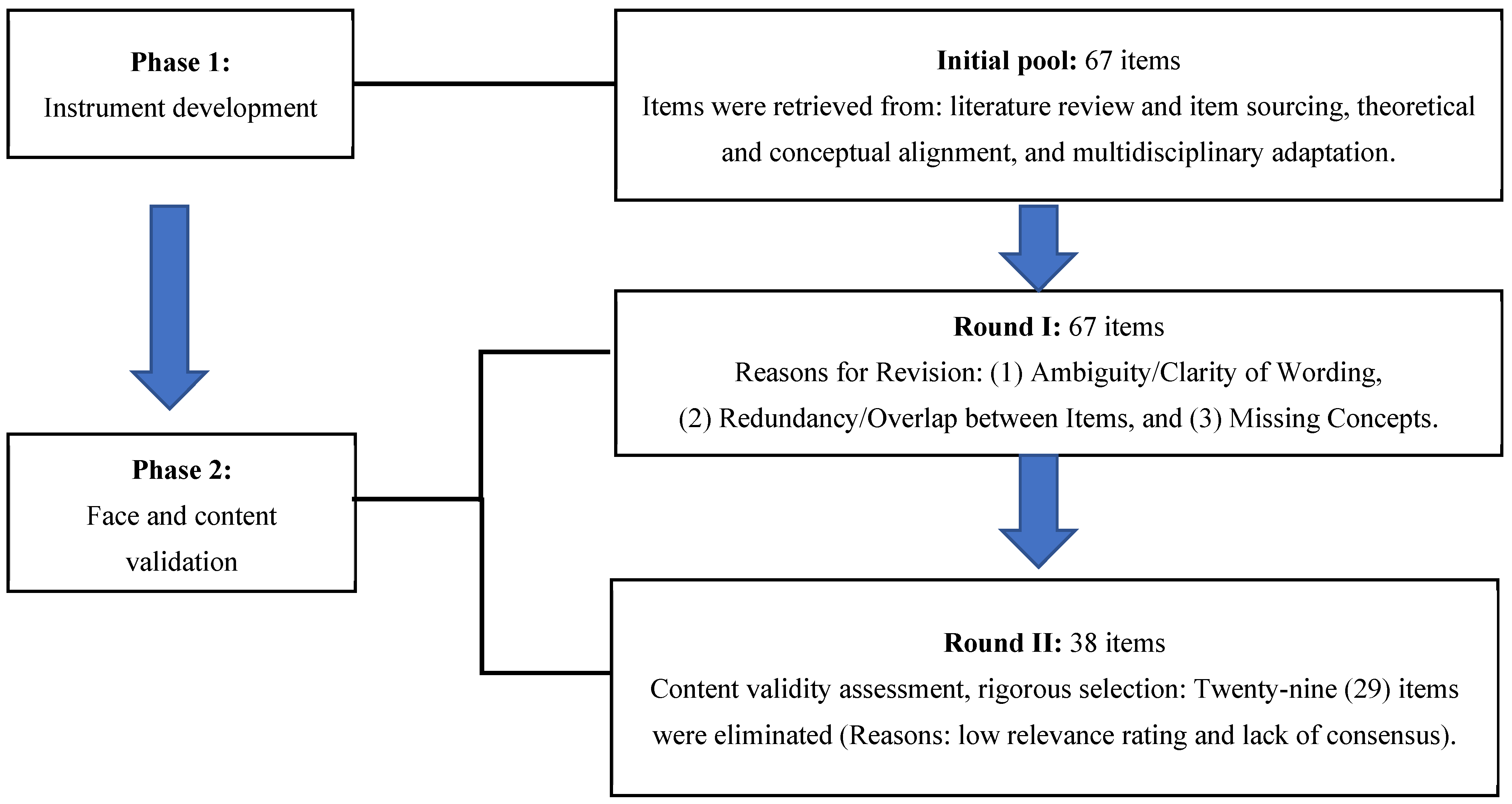

This process was conducted in two phases: (1) instrument development and (2) face and content validation.

2.2.1. Phase 1: Instrument Development

The draft TCCHI includes an initial pool of 67 items. This pool was developed using a three-step systematic process:

Literature Review and Item Sourcing: A comprehensive review was conducted of existing technological caring and general caring scales, primarily the Technological Competency as Caring in Nursing Instrument (TCCNI) and its revisions (TCCNI-R, PITCCN), as well as established general caring scales (e.g., CBI).

Theoretical and Conceptual Alignment: Items collected from these scales were synthesized, adapted, and newly generated to explicitly align with the six dimensions of the TCCH conceptual framework (see Section 2.1)

Multidisciplinary Adaptation: The language and context of the items were systematically reviewed and modified to be applicable across diverse healthcare professions (e.g., changing nursing-specific terminology to neutral language such as ‘healthcare professional’ or ‘provider’), ensuring that they reflect the intersection of technology and caring beyond the nursing domain.

2.2.2. Phase 2: Face and Content Validation

The reliability and validity of this study were ensured in accordance with the reporting guidelines for Delphi studies in health sciences [48]. A two-round modified Delphi study was conducted to obtain expert consensus on the TCCHI items. In Round 1, the experts evaluated the overall appropriateness and relevance (face validity) of the initial 67 items. Following revisions based on feedback from round 1, round 2 focused on establishing the content validity of the refined item set [49].

Justification for the Modified Delphi Approach: A modified Delphi approach was specifically chosen because the instrument is theoretically grounded in Locsin’s TCCN theory and built upon existing validated instruments. This allowed the research team to provide a theoretically grounded, pre-defined item pool (67 items) derived from a systematic literature review, rather than relying on the open item elicitation characteristic of a traditional, non-modified Delphi method.

Justification for Panel Size and Selection: The panel size of 10 was determined to be sufficient based on the methodological guidelines for scale development and content validation studies, which generally recommend expert panels ranging from 5 to 15 members to ensure diverse perspectives while maintaining manageability [50,51,52].

Purposive sampling was utilized to select experts who met the following predefined criteria essential for validating the multidisciplinary TCCHI: (1) expertise in Locsin’s TCCN theory, (2) a high academic degree (Master’s or PhD), and (3) experience across multiple healthcare disciplines (nursing, medicine, and physical therapy), reflecting the instrument’s intended broad applicability.

Ten experts with a solid understanding of Locsin’s theory participated in the two-round Delphi process. The panel comprised healthcare professionals specializing in nursing, medicine, patient care quality assurance, and healthcare research. The participants’ ages ranged from 30 to 60 years, with an average professional experience of 27.5 years. Seven were nurses, two were physiotherapists, and one was a physician, all of whom had master’s degrees or higher and expertise in TCCH. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the expert panel.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the expert panel.

Anonymity in the Delphi Process: To minimize potential status and group bias, anonymity was strictly preserved among the expert panel members throughout the two-round Delphi procedure. Each expert received the consensus results (median, standard deviation, and interquartile range of the group’s rating) from the previous round without identifying which specific ratings belonged to which individual. Data collection and analysis were managed solely by the primary research team, ensuring that individual responses were not shared among participants.

Panelists rated each item’s relevance and importance using a 9-point Likert scale across two rounds of the Delphi process. The level of consensus was calculated by summing the Likert scores, where 1 = Not at all important, 2 = Very unimportant, 3 = Not important, 4 = Somewhat unimportant, 5 = Neither important nor unimportant, 6 = Somewhat important, 7 = Important, 8 = Very important, and 9 = Extremely important [53]. The item-level content validity index (I-CVI) was calculated by dividing the number of experts who rated an item between 6 and 9 by the total number of experts. The minimum consensus level was set at I-CVI ≥ 0.78.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (median, minimum, and maximum) to determine the consensus level [54]. Microsoft Excel® was used for data entry and for tabulating the universal agreement (UA) for content validity calculation. A value of 1 was assigned when the experts were in perfect agreement, and 0 when they were not. Content validity was assessed using the Content Validity Index (CVI). The following indices were used: I-CVI—number of experts in agreement divided by the total number of experts; Scale-level Content Validity Index (S-CVI)/Ave (I-CVI-based): mean of I-CVI scores for all items; S-CVI/Average (based on percentage relevance)—mean of the percentage relevance scores from all experts; and S-CVI/UA—mean of UA scores for all items. The I-CVI was set at >0.78 for each item [55,56].

To enhance methodological rigor and demonstrate the response stability of expert ratings across the two Delphi rounds, additional inferential analyses were performed on the retained items (n = 38) and, for screening purposes, the entire 67-item set: (1) The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was used to determine whether there was a statistically significant change in the central tendency (median) of the ratings for each item between Rounds 1 and 2. A non-significant result (p > 0.05) was interpreted as stability in the expert group’s opinion [57]. (2) The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) and its 95% Confidence Interval (CI) were calculated using a two-way mixed-effects consistency model (ICC (3,1)) [58]. This assessment evaluated the inter-rater consistency of the expert panel’s agreement, further reinforcing the rigor of the consensus process. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS v27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Jamovi statistical software version 2.4.11.0 (The Jamovi Project, Sydney, Australia).

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1: Instrument Development and Qualitative Refinement

The TCCHI was developed and validated in two phases, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Item development process.

3.1.1. Initial Item Generation

An initial pool of 67 items was generated across six concepts (Table 2). These items were created by systematically reviewing and synthesizing existing scales and adapting the language to ensure applicability for multidisciplinary healthcare providers, explicitly aligning with the proposed conceptual framework of TCCHI (as defined in Section 2.1).

Table 2.

Developed TCCHI items.

3.1.2. Qualitative Feedback Analysis and Item Modification (Round 1)

The qualitative comments collected from the 10 experts in Round 1 were systematically analyzed by the research team. Based on this analysis, the research team implemented specific modifications to the wording and structure of the items. The revised set of all 67 items was then presented in Round 2 for formal content validity assessment.

3.2. Phase 2: Face and Content Validation (Quantitative Assessment)

3.2.1. Quantitative Consensus and Item Selection

A two-round modified Delphi study was conducted with a panel of 10 experts. Items were retained if they achieved a median rating of ≥7 and an I-CVI of ≥0.80, based on predefined consensus criteria. After two rounds, 38 of the 67 initial items (56.7%) were retained, while 29 items were deleted due to low relevance ratings or lack of consensus. This selection confirms the initial relevance of the retained items based on expert judgment.

3.2.2. Inter-Rater Reliability and Stability

The response stability of the expert panel was confirmed using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test, which showed no significant difference in the median scores for the retained items between Round 1 and Round 2 (p > 0.05). This indicates that the expert consensus was stable. However, inter-rater consistency was moderate, as reflected by the ICC for the retained items (Round 1: ICC = 0.486, 95% CI 0.291, 0.648; Round 2: ICC = 0.501, 95% CI 0.317, 0.655).

3.2.3. Final Instrument Structure

The final 38 retained items were distributed across the six refined concepts (Table 2) as follows:

Concept 1: Promoting self-growth and technological learning; six items (#58, 59, 60, 65, 66, and 67).

Concept 2: Building trusting relationships with patients; seven items (#1, 3, 7, 8, 9, 12, and 47).

Concept 3: Providing person-centered care through the appropriate use of technology; six items (#13, 15, 18, 23, 24, and 25).

Concept 4: Enhancing the physical and emotional comfort of patients; six items (#17, 29, 33, 35, 36, and 43).

Concept 5: Promoting patient learning and growth; six items (#14, 22, 40, 42, 45, and 46).

Concept 6: Engaging in ethico-moral practice regarding technology use and patient advocacy: seven items (#27, 48, 49, 53, 54, 55, and 56).

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

The two-round modified Delphi study successfully established the preliminary content validity of the TCCHI among a multidisciplinary expert panel. Of the initial 67 items, 38 were retained after meeting the criteria (I-CVI ≥ 0.80). This selection process ensures the foundational relevance of the final item set to the conceptual construct. Methodological rigor was confirmed by the stability of the expert ratings, demonstrated by a non-significant difference in the median ratings between Rounds 1 and 2 (p > 0.05). However, the inter-rater reliability remained moderate (ICC = 0.5), and the scale-level content validity index average was low (S-CVI/Ave = 0.55) must be interpreted within the context of preliminary validation and the instrument’s novel, multidisciplinary focus.

4.2. Comparison with the Literature

This study’s rigorous Delphi approach, which employed the I-CVI and Wilcoxon analysis to assess relevance and stability, aligns with best practices for instrument development [56,59]. Our achieved I-CVI of ≥0.80 for all retained items is consistent with the minimum acceptable consensus required in similar Delphi validation studies for complex health constructs [55,56]. Furthermore, the stability observed in the Wilcoxon test supports the consistency of the panel’s judgment, a key indicator of methodological quality in iterative expert consensus gathering [59,60].

4.3. Implications of Moderate Inter-Rater Reliability and Content Validity Results

Although methodological rigor was confirmed, the moderate ICC (0.5) and S-CVI/Ave (0.55) require specific contextual interpretation. We argue that the moderate ICC is a direct and necessary consequence of using a deliberately multidisciplinary expert panel (Medicine, Nursing, Physical Therapy). Experts from different professional scopes inherently view concepts like “technological competency” and “caring” through distinct lenses, leading to lower initial agreement but ultimately ensuring that the instrument is broadly applicable across healthcare disciplines rather than being biased toward a single profession. The initial lower consensus (S-CVI/Ave of 0.55) highlights the innovative yet challenging nature of extending Locsin’s nursing-centric TCCN theory into a genuinely interprofessional framework of TCCH, a challenge frequently encountered when adapting discipline-specific theories for multidisciplinary use [61]. These values underscore the preliminary nature of the findings, indicating a need for structural refinement in subsequent phases.

4.4. Alignment of High-Consensus Items with Theory and Practice

The consistently highly rated items demonstrate a strong expert consensus on the essential elements of TCCH, consistent with the extant literature. The high agreement on items related to person-centered care, trust, and ethico-moral practice (e.g., “Q 1, Always treating every patient with compassion,” “Q 3, Building relationships that patients can trust,” and “Q 47, Recognizing the patient as an individual and irreplaceable person”) confirms that the humanistic core of healthcare remains paramount [16], supporting the foundational premise of Locsin’s TCCN theory [62]. Moreover, the consensus on items concerning collaboration (e.g., “Q 13, Working with other professionals to support patients”) and the explicit link between technology and care (e.g., “Q 24, Technology is useful for correctly assessing a patient’s condition”) reflect a modern understanding of healthcare as a team-based, technology-mediated effort in which patient autonomy and empowerment are key [63,64,65]. These findings empirically support the extension of TCCN’s concepts to the broader healthcare context [4].

4.5. Implications

The development of the TCCHI addresses a significant gap by providing a multidisciplinary instrument, contrasting with earlier tools that were limited to nursing. The TCCHI is highly relevant to current global trends emphasizing person-centered, interprofessional care.

Practically, the developed TCCHI offers several key applications:

Evaluation: It can be used to evaluate and compare healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward patients and technology, promoting a unified direction within the healthcare team.

Education and Training: The instrument can serve as an educational tool for healthcare personnel, providing a structured framework to enhance caring skills and ethical awareness across multiple disciplines.

Hierarchical Assessment: It can support the hierarchical evaluation of multidisciplinary healthcare professionals in hospital settings, leveraging differences in caring skills to optimize team composition.

4.6. Study Limitations

Despite the rigorous content validation process, this study has some inherent limitations. The Delphi panel included only 10 experts. While this size is consistent with some methodological guidelines for content validity [50,51,52], it may still limit the initial generalizability of the consensus. Moreover, the panel, although diverse in professional representation, was predominantly composed of nurses (n = 7). This limited representation of other disciplines, such as physical therapists (n = 2) and physicians (n = 1), may introduce professional bias and impact the generalizability of the content validation. We recommend that future validation studies include a more balanced representation of medicine, social work, and other healthcare fields to minimize this bias. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and reliability tests will be conducted in the future to further refine the internal structure of the scale and assess its psychometric properties across diverse clinical samples.

5. Conclusions

The development of the TCCHI successfully extends Locsin’s TCCN theory to a multidisciplinary healthcare context. As the first instrument designed for this purpose, the TCCHI provides a theoretically grounded framework for measuring healthcare professionals’ integrated ability to utilize technological competency with ethical, person-centered care practices. This ensures that technology consistently serves to enhance patient dignity and holistic well-being within modern, team-based healthcare settings.

This study establishes the foundational content validity of the TCCHI; however, the next crucial step involves further psychometric validation. Future research will focus on large-scale data collection to conduct CFA to confirm the instrument’s factorial structure and assess its internal consistency and reliability across diverse professional populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Y., K.S. and T.T.; methodology, R.Y., H.I., M.M. and T.T.; validation, M.K., H.I., Y.Z., M.A., F.B., G.P.S., A.P.B., R.T. and S.S.; formal analysis, M.M., H.I., R.T. and T.T.; investigation, R.Y., Y.N., M.M., F.B., K.O. (Kaito Onishi), G.P.S. and T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y., R.Y., K.S., H.I., K.O. (Kyoko Osaka), M.M., Y.T. and T.T.; supervision M.A. and M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokushima University Hospital (#4591, 30 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. These data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude for the collaboration and assistance received during the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TCCN | Technological Competency as Caring in Nursing |

| TCCNI | Technological Competency as Caring in Nursing Instrument |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| TCCH | Technological Competency as Caring in Healthcare |

| TCCHI | Technological Competency as Caring in Healthcare Providers Instrument |

| I-CVI | Item-level Content Validity Index |

| UA | Universal agreement |

| S-CVI | Scale-level Content Validity Index |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CBI | Caring Behaviors Inventory |

| CARE-Q | Report Evaluation Q-sort |

| TCCNI-R | Technological Competency Caring in Nursing Instrument-Revised |

| PITCCN | Perceived Inventory of Technological Competency as Caring in Nursing |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

References

- Astier, A.; Carlet, J.; Hoppe-Tichy, T.; Jacklin, A.; Jeanes, A.; McManus, S.; Pletz, M.W.; Seifert, H.; Fitzpatrick, R. What is the role of technology in improving patient safety? A French, German and UK healthcare professional perspective. J. Patient Saf. Risk Manag. 2020, 25, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krel, C.; Vrbnjak, D.; Bevc, S.; Štiglic, G.; Pajnkihar, M. Technological competency as caring in nursing: A description, analysis and evaluation of the theory. Zdr. Varst. 2022, 61, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locsin, R.C. The co-existence of technology and caring in the theory of technological competency as caring in nursing. J. Med. Invest. 2017, 64, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locsin, R.C.; Schoenhofer, S.O. Technology as lens for knowing person as caring. Belitung Nurs. J. 2025, 11, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J. Compilation and Summary Data of Each Instrument for Measuring Caring. In Assessing and Measuring Caring in Nursing and Health Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Larrabee, J.H.; Putman, H.P. Caring behaviors inventory: A reduction of the 42-item instrument. Nurs. Res. 2006, 55, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuckett, A.G.; Hughes, K.; Schluter, P.J.; Turner, C. Validation of CARE-Q in residential aged-care: Rating of importance of caring behaviours from an E-cohort sub-study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locsin, R.C. Development of an instrument to measure technological caring in nursing. Nurs. Health Sci. 1999, 1, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcells, D.A.; Locsin, R.C. Development and psychometric testing of the technological competency as caring in nursing instrument. Int. J. Hum. Caring 2011, 15, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Kongsuwan, W.; Matchim, Y. Technological competency as caring in nursing as perceived by ICU nurses in Bangladesh and its related factors. Songklanagarind J. Nurs. 2016, 36, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Yokotani, T.; Tanioka, T.; Betriana, F.; Yasuhara, Y.; Ito, H.; Soriano, G.P.; Dino, M.J.; Locsin, R.C. Psychometric testing of the technological competency as caring in nursing instrument—Revised (English version including a practice dimension). Nurs. Med. J. Nurs. 2021, 11, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Miyagawa, M.; Yasuhara, Y.; Osaka, K.; Kataoka, M.; Ito, H.; Tanioka, T.; Locsin, R.; Kongswan, W. Recognition and status of practicing technological competency as caring in nursing by nurses in ICU. Int. J. Nurs. Clin. Pract. 2017, 4, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maydick Youngberg, D.R.; Jankowski, I. The multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary teamwork across care settings and transitions of care. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2025, 60, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNally, S.; McNally, S. Scarlett McNally: Recognising the complexity of healthcare to deliver better health. BMJ 2025, 389, r834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, R.A.; Aiken, L.H.; Mechanic, D.; Moravcsik, J. Organizational aspects of caring. Milbank Q. 1995, 73, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollos, L.A.C.L.; Zhao, Y.; Soriano, G.P.; Tanioka, T.; Otsuka, H.; Locsin, R. Technologies, physician’s caring competency, and patient centered care:A systematic review. J. Med. Investig. 2023, 70, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongen, P.J. Information and communication technology medicine: Integrative specialty for the future of medicine. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2023, 12, e42831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, A.; González-Ortiz, L.G.; Gabutti, L.; Lumera, D. What’s the role of kindness in the healthcare context? A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwame, A.; Petrucka, P.M. A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: Barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.C.; Dwamena, F.C.; Fortin, A.H. Teaching personal awareness. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005, 20, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Benner, P. From novice to Expert, excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 1984, 84, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patistea, E.; Siamanta, H. A literature review of patients’ compared with nurses’ perceptions of caring: Implications for practice and research. J. Prof. Nurs. 1999, 15, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Fruchter, N.; Dabbish, L. Making decisions from a distance: The impact of technological mediation on riskiness and dehumanization. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–18 March 2015; pp. 1576–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, M.S. Caring, the Human Mode of Being: A Blueprint for the Health Professions, 2nd ed.; Canadian Healthcare Association Press: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Björnsdóttir, K. From the state to the family: Reconfiguring the responsibility for long-term nursing care at home. Nurs. Inq. 2002, 9, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, C.H.; Arthur, D.; Sohng, K.Y. Relationship between technological influences and caring attributes of Korean nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2002, 8, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, K.; Slevin, E. The meaning of caring to nurses: An investigation into the nature of caring work in an Intensive Care Unit. J. Clin. Nurs. 2004, 13, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, L.M.; Lepore, M.; Wiener, J.M. Patient-centered, person-centered, and person-directed care: They are not the same. Med. Care 2015, 53, 561–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, A.; Oldham, J. Person-centred care: What is it and how do we get there? Future Hosp. J. 2016, 3, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wensley, C.; Botti, M.; McKillop, A.; Merry, A.F. Maximising comfort: How do patients describe the care that matters? A two-stage qualitative descriptive study to develop a quality improvement framework for comfort-related care in inpatient settings. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veale, D.; Robins, E.; Thomson, A.B.; Gilbert, P. No safety without emotional safety. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elendu, C.; Amaechi, D.C.; Okatta, A.U.; Amaechi, E.C.; Elendu, T.C.; Ezeh, C.P.; Elendu, I.D. The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e38813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A.; DiazGranados, D.; Dietz, A.S.; Benishek, L.E.; Thompson, D.; Pronovost, P.J.; Weaver, S.J. Teamwork in healthcare: Key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, G.A.L.; Pedram, S.; Sanzone, S. Improving safety outcomes through medical error reduction via virtual reality-based clinical skills training. Saf. Sci. 2023, 165, 106200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambushe, S.A.; Awoke, N.; Demissie, B.W.; Tekalign, T. Holistic nursing care practice and associated factors among nurses in public hospitals of Wolaita zone, South Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omuya, H.; Kuo, W.C.; Chewning, B. Innate psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and provider communication as determinants of patients’ satisfaction and self-rated health. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2025, 37, mzaf036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entwistle, V.A.; Carter, S.M.; Cribb, A.; McCaffery, K. Supporting patient autonomy: The importance of clinician-patient relationships. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, M.; Kinn, S. Defining and measuring patient-centred care: An example from a mixed-methods systematic review of the stroke literature. Health Expect. 2012, 15, 295–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, W.; Kueper, J.K.; Lin, S.; Bazemore, A.; Kakadiaris, I. Competencies for the use of artificial intelligence in primary care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2022, 20, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Cope, G.; Nelson, A.L.; Patterson, E.S. Patient Care technology and safety. In Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses; Advances in Patient Safety; Hughes, R.G., Ed.; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, Y.K.; Federico, F. The impact of health information technology on patient safety. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, S.T. The role of caring in a theory of nursing ethics. Hypatia 1989, 4, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemparaj, V.M.; Kadalur, U.G. Understanding the principles of ethics in health care: A systematic analysis of qualitative information. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2018, 5, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdeniz, M.; Yardımcı, B.; Kavukcu, E. Ethical considerations at the end-of-life care. Sage Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211000918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, A.; Entwistle, V.; Gilbert, D. Sharing decisions with patients: Is the information good enough? BMJ 1999, 318, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolt, M.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Ruokonen, M.; Repo, H.; Suhonen, R. Ethics interventions for healthcare professionals and students: A systematic review. Nurs. Ethics 2018, 25, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drolet, M.-J. A typology of ethical issues to better support the development of ethical sensitivity among healthcare professionals. Can. J. Bioeth. 2024, 7, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spranger, J.; Homberg, A.; Sonnberger, M.; Niederberger, M. Reporting guidelines for Delphi techniques in health sciences: A methodological review. Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes 2022, 172, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heufel, M.; Kourouche, S.; Mitchell, R.; Cardona, M.; Thomas, B.; Lo, W.A.; Murgo, M.; Vergan, D.; Curtis, K. Development of an audit tool to evaluate end of life care in the emergency department: A face and content validity study. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2025, 31, e70041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akins, R.B.; Tolson, H.; Cole, B.R. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: Application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2005, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vet, E.; Brug, J.; De Nooijer, J.; Dijkstra, A.; De Vries, N.K. Determinants of forward stage transitions: A Delphi study. Health Educ. Res. 2004, 20, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrego, M.F.; Colbert, A.M.; Ewing-Cobbs, L.; Andreu, M.F. Cultural adaptation and validation of the argentine children’s orientation and amnesia test. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, K.; Bernstein, S.; Aguilar, M.D.; Burnand, B. The RAND/UCLA. Appropriateness Method User’s Manual; RAND: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 0-8330-2918-5. [Google Scholar]

- Trevelyan, E.G.; Robinson, P.N. Delphi methodology in Health Research: How to do it? Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2015, 7, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T.; Owen, S.V. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holey, E.A.; Feeley, J.L.; Dixon, J.; Whittaker, V.J. An exploration of the use of simple statistics to measure consensus and stability in Delphi studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohapatra, S.; Maiya, G.A.; Nayak, U.U.; Sheelvant, R.; Watson, J.; Nandineni, R.D. Justice-centered best practices for accessibility to public buildings in a tier II City: Insights from a Delphi Expert Consensus. F1000Research 2024, 13, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z. Use of Delphi in health sciences research: A narrative review. Medicine 2023, 102, e32829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenaszchuk, C.; Reeves, S.; Nicholas, D.; Zwarenstein, M. Validity and reliability of a multiple-group measurement scale for interprofessional collaboration. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaii, A.; Mohammadi, E.; Sadooghiasl, A. The meaning of the empathetic nurse-patient communication: A qualitative study. J. Patient Exp. 2021, 8, 23743735211056432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care; Board on Health Care Services; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care; McCauley, L., Phillips, R.L., Meisnere, M., Robinson, S.K., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 1–428. ISBN 978-0-309-68510-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mesko, B.; deBronkart, D.; Dhunnoo, P.; Arvai, N.; Katonai, G.; Riggare, S. The evolution of patient empowerment and its impact on health care’s future. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e60562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, E.; Richter, P.; Schlieter, H. All together now—Patient engagement, patient empowerment, and associated terms in personal healthcare. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).