The Moderating Effect of Generation on the Association Between Long Working Hours and Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Study of Korean Employees

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Clinical Assessments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Demographic Characteristics

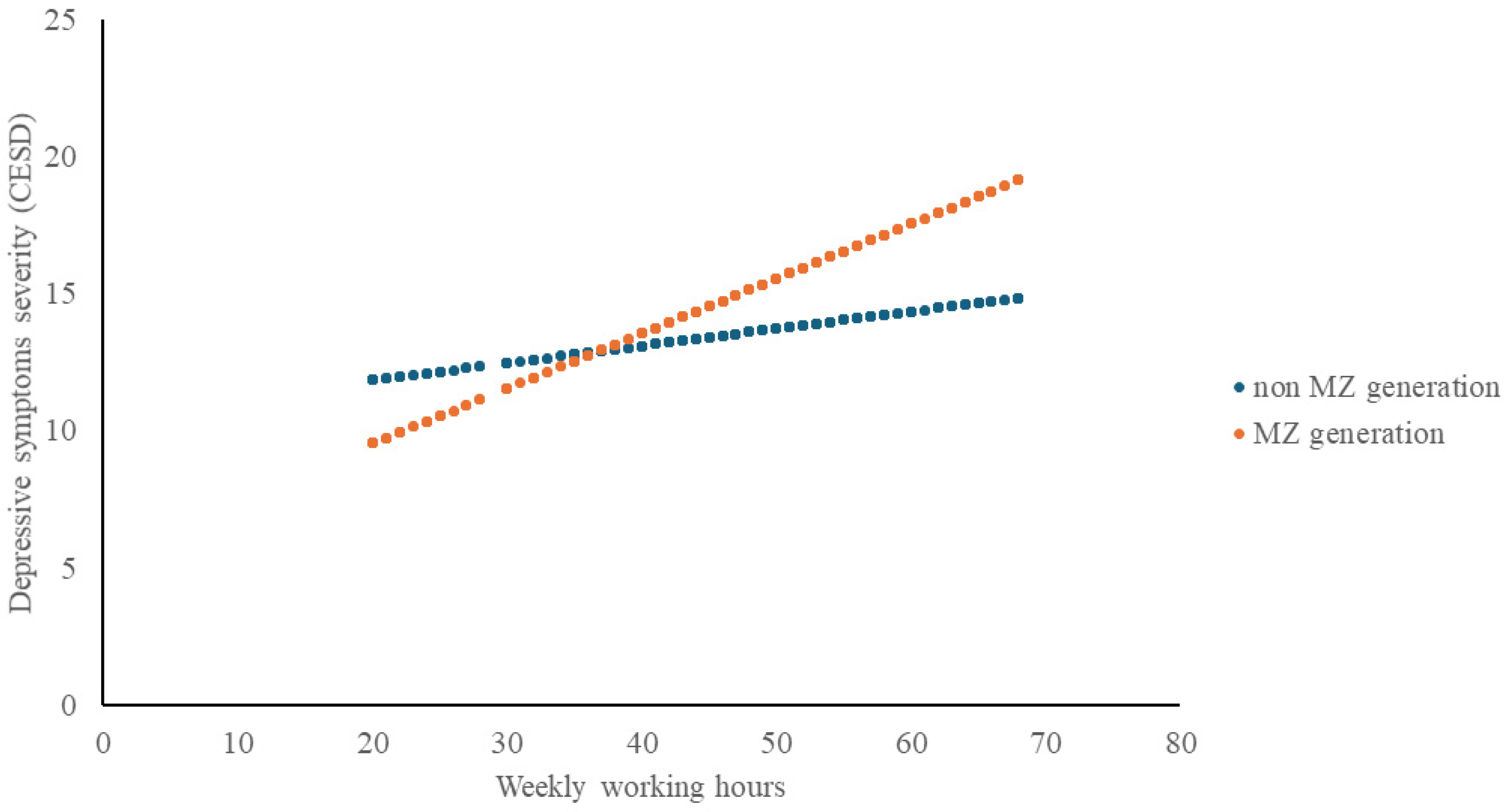

3.2. Association Between Weekly Working Hours, Generation, and Depressive Symptoms

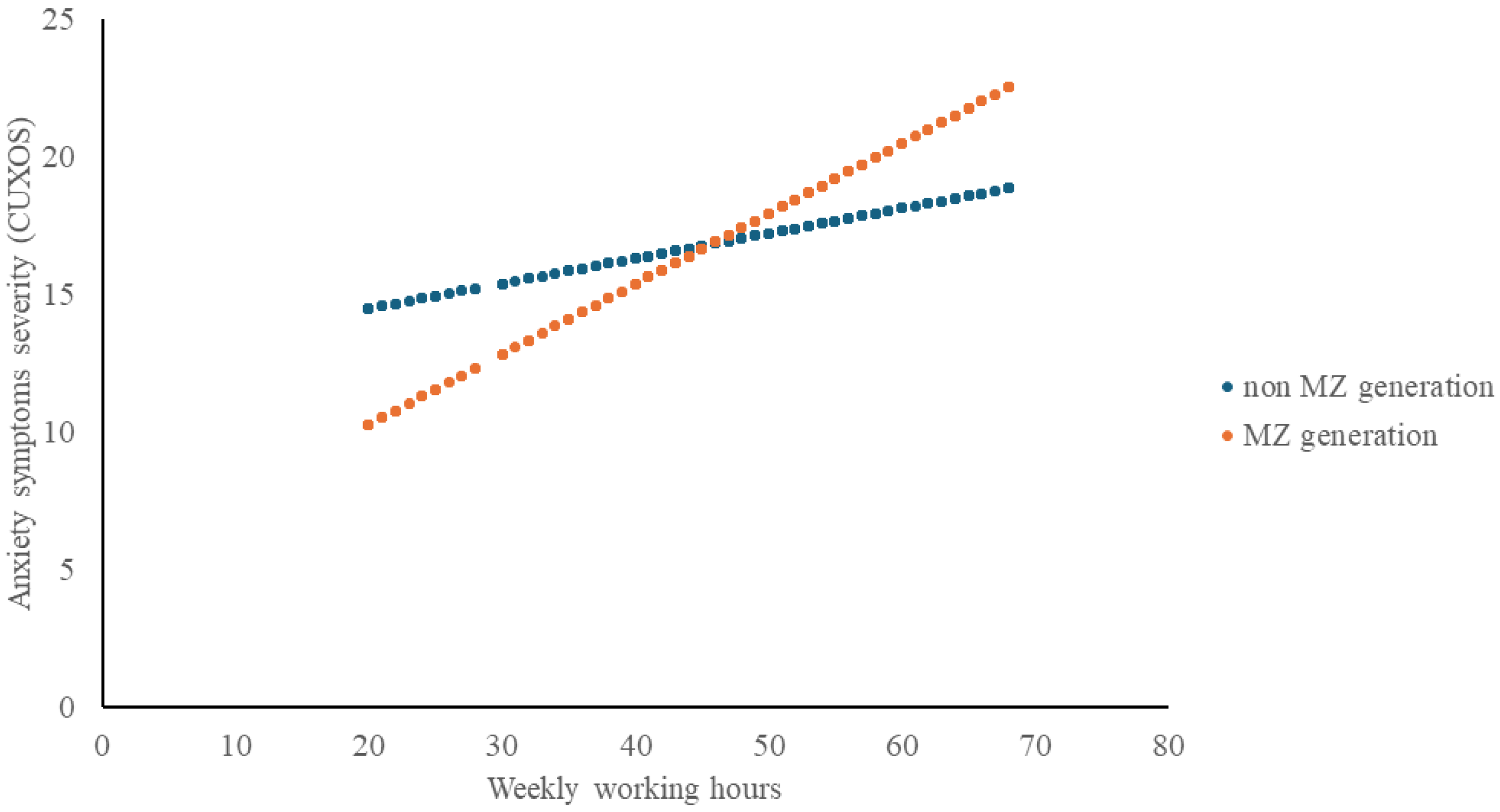

3.3. Association Between Weekly Working Hours, Generation, and Anxiety Symptoms

3.4. Exploratory Three-Way Interaction Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CES-D | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale |

| CUXOS | Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale |

| MZ | Millennial and Generation Z (participants born on or after 1 January 1980) |

| KRW | Korean Won |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination (R-squared) |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Tisu, L.; Rusu, A.; Sulea, C.; Vîrgă, D. Job resources and strengths use in relation to employee performance: A contextualized view. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 125, 1494–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basit, A.; Hassan, Z. Impact of job stress on employee performance. Int. J. Account. Bus. Manag. 2017, 5, 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.; An, Y.; Jeon, S.W.; Cho, S.J. Predicting depressive symptoms in employees through life stressors: Subgroup analysis by gender, age, working hours, and income level. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1495663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Knapp, M. Global patterns of workplace productivity for people with depression: Absenteeism and presenteeism costs across eight diverse countries. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 1525–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, C.; Gordon, R.; Robinson, L.; Caputi, P.; Oades, L. Workplace bullying and absenteeism: The mediating roles of poor health and work engagement. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, K.; Cooper, C.L.; Fried, Y.; Shirom, A. The effects of working hours on health: A meta-analytic review. In From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 1: The Theory and Research on Occupational Stress and Wellbeing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 292–314. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.; Chan, A.H.; Ngan, S. The effect of long working hours and overtime on occupational health: A meta-analysis of evidence from 1998 to 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, M.; Ferrie, J.E.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Shipley, M.J.; Stansfeld, S.A.; Marmot, M.G.; Ahola, K.; Vahtera, J.; Kivimäki, M. Long working hours and symptoms of anxiety and depression: A 5-year follow-up of the Whitehall II study. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 2485–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Shin, Y.C.; Lee, M.Y.; Oh, K.-S.; Shin, D.-W.; Kim, E.S.; Kim, M.-K.; Jeon, S.-W.; Cho, S.J. Occupational stress and depression of Korean employees: Moderated mediation model of burnout and grit. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.J.; Shin, Y.C.; Oh, K.-S.; Shin, D.-W.; Jeon, S.-W.; Cho, S.J. Examining the links between burnout and suicidal ideation in diverse occupations. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1243920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market, O. OECD Employment Outlook. 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-employment-outlook-2024_ac8b3538-en.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Jung, S.; Lee, H.-J.; Lee, M.Y.; Kim, E.S.; Jeon, S.-W.; Shin, D.-W.; Shin, Y.-C.; Oh, K.-S.; Kim, M.-K.; Cho, S.J. Gender differences in the association between workplace bullying and depression among Korean employees. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Oh, D.j.; Kim, J.; Oh, K.-S.; Shin, Y.C.; Shin, D.; Cho, S.J.; Jeon, S.-W. Revealing the confluences of workplace bullying, suicidality, and their association with depression. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Shin, Y.-C.; Oh, K.-S.; Shin, D.-W.; Lim, W.-J.; Cho, S.J.; Jeon, S.-W. Association between work stress and risk of suicidal ideation. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2020, 46, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; González-López, Ó.R.; Buenadicha-Mateos, M.; Tato-Jiménez, J.L. Work-life balance in great companies and pending issues for engaging new generations at work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waworuntu, E.C.; Kainde, S.J.; Mandagi, D.W. Work-life balance, job satisfaction and performance among millennial and Gen Z employees: A systematic review. Society 2022, 10, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabahani, P.R.; Riyanto, S. Job satisfaction and work motivation in enhancing generation Z’s organizational commitment. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 1, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroth, H. Are you ready for Gen Z in the workplace? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 61, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omilion-Hodges, L.M.; Sugg, C.E. Millennials’ views and expectations regarding the communicative and relational behaviors of leaders: Exploring young adults’ talk about work. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q. 2019, 82, 74–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Jeon, H.; Lee, M.Y.; Kim, E.; Shin, D.-W.; Shin, Y.-C.; Oh, K.-S.; Kim, M.-K.; Jeon, S.-W.; Cho, S.J. Gender Difference of Moderated Mediating Effect of Grit Between Occupational Stress and Suicidal Ideation in Korean Workers. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2024, 39, e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Masukujjaman, M.; Al Mamun, A.; Gao, J.; Makhbul, Z.K.M. Modeling the significance of work culture on burnout, satisfaction, and psychological distress among the Gen-Z workforce in an emerging country. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Dexter, C.; Kinsey, R.; Parker, S. Meaningful work and mental health: Job satisfaction as a moderator. J. Ment. Health 2018, 27, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasi, S.N. Perceived influence of work relationship, work load and physical work environment on job satisfaction of librarians in South-West, Nigeria. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2020, 69, 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea, S. Survey on Labor and Income 2023. 2025. Available online: https://www.kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301010000&bid=11113&list_no=435195&act=view&mainXml=Y (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Barhate, B.; Dirani, K.M. Career aspirations of generation Z: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2022, 46, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Oh, S.-T.; Ryu, S.-Y.; Jun, J.-Y.; Lee, K.; Lee, E.; Park, J.-Y.; Yi, S.-W.; Choi, W.-J. Validation of the Korean version of center for epidemiologic studies depression scale-revised (K-CESD-R). Korean J. Psychosom. Med. 2016, 24, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cosco, T.D.; Prina, M.; Stubbs, B. Reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in a population-based cohort of middle-aged US adults. J. Nurs. Meas. 2017, 25, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.W.; Han, C.; Ko, Y.-H.; Yoon, S.; Pae, C.-U.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.-M.; Yoon, H.-K.; Lee, H.; Patkar, A.A. A Korean validation study of the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale: Comorbidity and differentiation of anxiety and depressive disorders. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.; Chelminski, I.; Young, D.; Dalrymple, K. A clinically useful anxiety outcome scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nguyen, P.; Trieu, H.D.X.; Ton, U.N.H.; Dinh, C.Q.; Tran, H.Q. Impacts of career adaptability, life meaning, career satisfaction, and work volition on level of life satisfaction and job performance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Lett. 2021, 9, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, M.; Khanum, M.; Mufassir, D.; Rizvi, T.; Muzaffar, R.; Shoaib, S. Relationship of learned helplessness and social integration with psychological distress in medical students. Khyber Med. Univ. J. 2022, 14, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinou, G.; Attia, M. Perspective Chapter: From the Boom to Gen Z–Has Depression Changed across Generations? In Depression-What Is New and What Is Old in Human Existence; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rue, P. Make way, millennials, here comes Gen Z. About Campus 2018, 23, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwieger, D.; Ladwig, C. Reaching and retaining the next generation: Adapting to the expectations of Gen Z in the classroom. Inf. Syst. Educ. J. 2018, 16, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mude, G.; Undale, S. Social media usage: A comparison between Generation Y and Generation Z in India. Int. J. E-Bus. Res. (IJEBR) 2023, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PrakashYadav, G.; Rai, J. The Generation Z and their social media usage: A review and a research outline. Glob. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2017, 9, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Vallerand, R.J. The effects of work motivation on employee exhaustion and commitment: An extension of the JD-R model. Work Stress 2012, 26, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, S.P.; Prasad, P.; Raghuvamshi, G. Mental health awareness and generation gap. Indian J. Psychiatry 2022, 64, S636. [Google Scholar]

- Dolot, A. The characteristics of Generation Z. E-Mentor 2018, 74, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, A.; Eyre, O.; Patel, V.; Brent, D. Depression in young people. Lancet 2022, 400, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtabai, R.; Olfson, M.; Han, B. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vultaggio, G. “The Most Anxious Generation”: The Relationship Between Gen Z Students, Social Media, and Anxiety. 1916. Available online: https://soar.suny.edu/entities/publication/a6a9a6e0-7732-46d0-afcd-f36b7794b05c (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Tsevreni, I.; Proutsos, N.; Tsevreni, M.; Tigkas, D. Generation Z worries, suffers and acts against climate crisis—The potential of sensing children’s and young people’s eco-anxiety: A critical analysis based on an integrative review. Climate 2023, 11, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunau, T.; Wahrendorf, M.; Dragano, N.; Siegrist, J. Work stress and depressive symptoms in older employees: Impact of national labour and social policies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 11,372) | Non-MZ (n = 3834) | MZ (n = 7538) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 36.72 ± 9.43 | 47.70 ± 5.08 | 31.14 ± 5.34 | <0.001 |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||

| Male, n (%) | 7737 (68.0) | 2775 (72.4) | 4962 (65.8) | |

| Female, n (%) | 3635 (32.0) | 1059 (27.6) | 2576 (34.2) | |

| Education (graduate) | <0.001 | |||

| College graduate or below, n (%) | 2759 (24.3) | 907 (23.7) | 1852 (24.6) | |

| University graduate, n (%) | 6837 (60.1) | 1950 (50.9) | 4887 (64.8) | |

| Master’s degree or higher, n (%) | 1776 (15.6) | 977 (25.5) | 799 (10.6) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married, n (%) | 6366 (56.0) | 3389 (88.4) | 2977 (39.5) | |

| Unmarried, n (%) | 4808 (42.3) | 313 (8.2) | 4498 (59.6) | |

| Other, n (%) | 198 (1.7) | 132 (3.4) | 66 (0.9) | |

| Years of service (years), mean ± SD | 10.55 ± 9.09 | 19.10 ± 9.57 | 6.20 ± 4.68 | <0.001 |

| Hours of work per week (hours), mean ± SD | 46.82 ± 7.53 | 46.14 ± 8.34 | 47.17 ± 7.06 | <0.001 |

| Monthly earned income (million won) | <0.001 | |||

| Less than 3 million won, n (%) | 2949 (25.9) | 354 (9.2) | 2595 (34.4) | |

| 3–4 million won, n (%) | 3046 (26.8) | 639 (16.7) | 2407 (31.9) | |

| Over 4 million won, n (%) | 4660 (41.0) | 2571 (67.1) | 2089 (27.7) | |

| Missing, n (%) | 717 (6.3) | 270 (7.0) | 447 (5.9) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| CES-D score, mean ± SD | 17.08 ± 14.59 | 13.50 ± 9.63 | 14.99 ± 10.16 | <0.001 |

| CUXOS score, mean ± SD | 16.85 ± 5.42 | 16.85 ± 14.14 | 17.19 ± 14.82 | 0.230 |

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p-Value | B | SE | t | p-Value | |

| Age | 0.018 | 0.017 | 1.020 | 0.308 | 0.098 | 0.022 | 4.511 | <0.001 |

| Sex (Female) | 3.834 | 0.205 | 18.744 | <0.001 | 3.984 | 0.203 | 19.639 | <0.001 |

| Education (University graduate) | 1.255 | 0.234 | 5.362 | <0.001 | 1.121 | 0.232 | 4.827 | <0.001 |

| Education (Master’s degree or higher) | −0.087 | 0.334 | −0.260 | 0.795 | −0.032 | 0.330 | −0.097 | 0.923 |

| Marital status (Unmarried) | 1.629 | 0.244 | 6.687 | <0.001 | 1.514 | 0.242 | 6.252 | <0.001 |

| Marital status (Other) | 3.827 | 0.707 | 5.411 | <0.001 | 3.941 | 0.700 | 5.629 | <0.001 |

| Years of service | 0.018 | 0.016 | 1.124 | 0.261 | 0.032 | 0.016 | 1.981 | 0.048 |

| Income (3–4 million won) | 0.232 | 0.262 | 0.886 | 0.375 | −0.131 | 0.260 | −0.504 | 0.614 |

| Income (Over 4 million won) | −0.560 | 0.278 | −2.011 | 0.044 | −0.943 | 0.277 | −3.407 | <0.001 |

| Working hour (centered) | 0.080 | 0.019 | 4.249 | <0.001 | ||||

| MZ generation | 1.942 | 0.352 | 5.524 | <0.001 | ||||

| Working hour (centered) × MZ generation | 0.140 | 0.025 | 5.710 | <0.001 | ||||

| R2 | 0.051 | 0.071 | ||||||

| F | 61.028 ** | 66.400 ** | ||||||

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p-Value | B | SE | t | p-Value | |

| Age | 0.098 | 0.025 | 3.930 | <0.001 | 0.204 | 0.032 | 6.465 | <0.001 |

| Sex (Female) | 6.783 | 0.296 | 22.887 | <0.001 | 6.992 | 0.294 | 23.764 | <0.001 |

| Education (University graduate) | 2.273 | 0.339 | 6.703 | <0.001 | 2.094 | 0.337 | 6.215 | <0.001 |

| Education (Master’s degree or higher) | −0.028 | 0.483 | −0.058 | 0.954 | 0.047 | 0.479 | 0.098 | 0.922 |

| Marital status (Unmarried) | −0.036 | 0.353 | −0.103 | 0.918 | −0.197 | 0.351 | −0.561 | 0.575 |

| Marital status (Other) | 2.616 | 1.025 | 2.553 | 0.011 | 2.779 | 1.016 | 2.736 | 0.006 |

| Years of service | 0.014 | 0.023 | 0.597 | 0.551 | 0.032 | 0.024 | 1.354 | 0.176 |

| Income (3–4 million won) | 0.209 | 0.379 | 0.550 | 0.582 | −0.284 | 0.378 | −0.751 | 0.452 |

| Income (Over 4 million won) | −1.692 | 0.403 | −4.195 | <0.001 | −2.214 | 0.401 | −5.516 | <0.001 |

| Working hour (centered) | 0.119 | 0.027 | 4.363 | <0.001 | ||||

| MZ generation | 2.526 | 0.510 | 4.954 | <0.001 | ||||

| Working hour (centered) × MZ generation | 0.182 | 0.036 | 5.126 | <0.001 | ||||

| R2 | 0.063 | 0.080 | ||||||

| F | 75.766 ** | 75.867 ** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jung, S.; An, Y.; Jeon, S.-W.; Kim, J.; Kim, E.; Yang, J.H.; Cho, S.J. The Moderating Effect of Generation on the Association Between Long Working Hours and Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Study of Korean Employees. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3002. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233002

Jung S, An Y, Jeon S-W, Kim J, Kim E, Yang JH, Cho SJ. The Moderating Effect of Generation on the Association Between Long Working Hours and Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Study of Korean Employees. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3002. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233002

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Sra, Yoosuk An, Sang-Won Jeon, Junhyung Kim, Eunsoo Kim, Jeong Hun Yang, and Sung Joon Cho. 2025. "The Moderating Effect of Generation on the Association Between Long Working Hours and Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Study of Korean Employees" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3002. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233002

APA StyleJung, S., An, Y., Jeon, S.-W., Kim, J., Kim, E., Yang, J. H., & Cho, S. J. (2025). The Moderating Effect of Generation on the Association Between Long Working Hours and Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Study of Korean Employees. Healthcare, 13(23), 3002. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233002