Evaluating Suicidal Risk in GLP-1RA Therapy: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analytic Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Procedures

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.4. Pre-Registration

3. Results

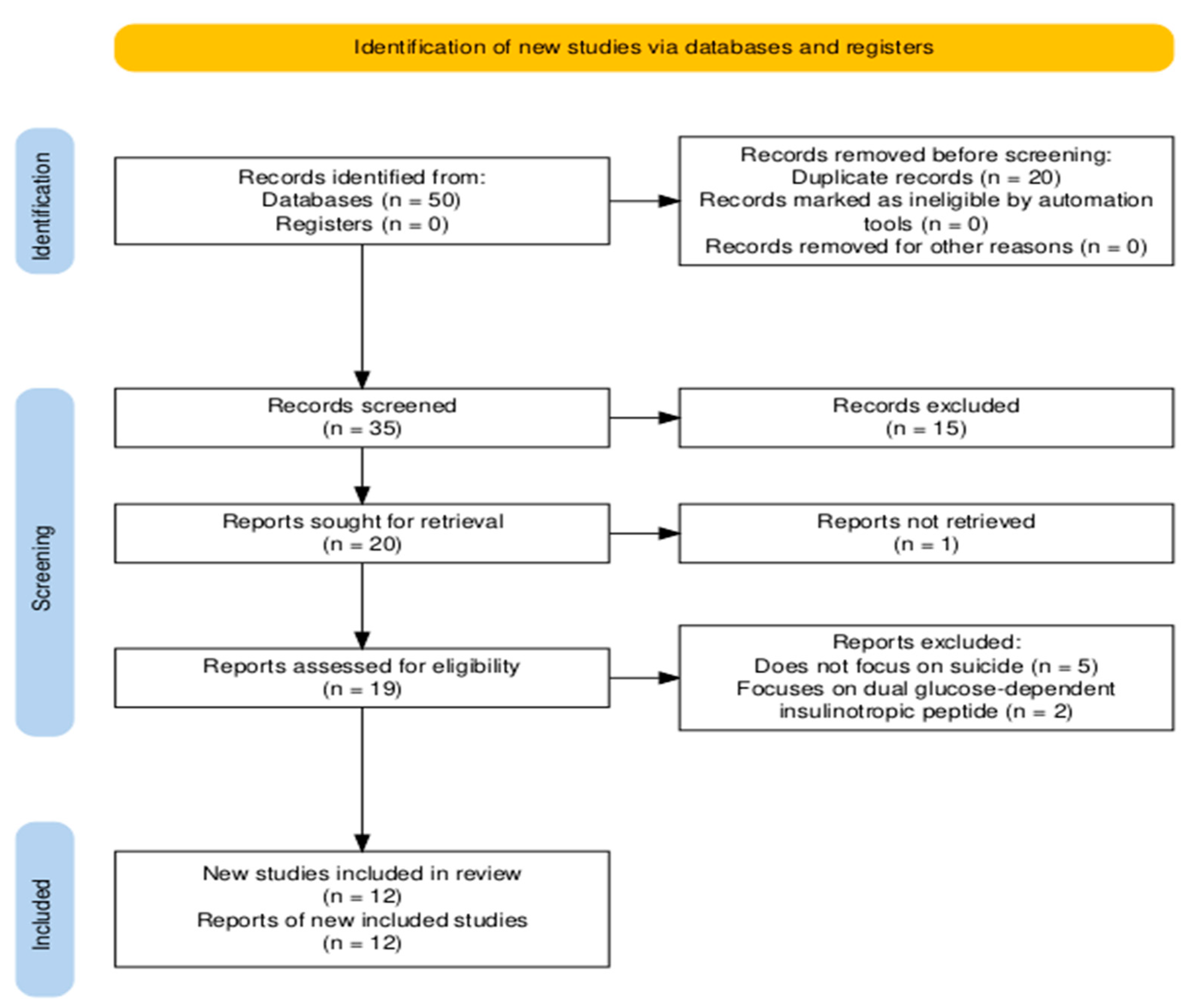

3.1. Selection of Studies

3.2. Study Characteristics

| Study | Psychological Disorder | Study Type | Type of the Included Studies | N of Studies | N Databases | Quality of Studies | N Sample | Mean Age | Gender Prevalence | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barroso [27] | MDD | systematic review | RCTs and prospective cohort studies | 7 | 3 (PubMed, Google Académico, Cochrane) | No | no synthesized details regarding study characteristics | N/R | N/R | patients with type 2 diabetes |

| Breit [28] | mental health | systematic review | RCTs (17), CTs (clinical trials, 2), prospective observational studies (7), retrospective (4), retrospective case series (1), two open-label studies (2), and post hoc pooled analyses (3). | 36 | 2 (PubMed, Cochrane Library) | No | samples range: 6–5325 participants | N/R | N/R | overweight patients (all studies), 18 studies on mental illness (schizoaffective disorders bipolar, depression, or the whole spectrum of disorders), and 21 studies on patients with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes |

| Bushi [29] | suicide risk (suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, suicidal behaviors, and self-injury) | systematic review and meta-analysis | observational cohort (10) and case-control (1) studies | 11 | 3 (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science) | although a quality assessment was performed, no results were reported. | samples range: 6–5325 participants | range from 46.6 to 65.9 years old | N/R | ranged from type 2 diabetes patients, to overweight/ obese adults, to general users of GLP-1RAs. |

| Di Stefano [30] | suicidality | systematic review | observational cohorts (5), RCTs (2), pharmacovigilance disproportionality analyses (8), post hoc RCT analysis (1) | 16 | 3 (MEDLINE, Embase, APA PsycInfo) | both observational and randomized studies were assessed as having a low risk of bias | N/R | >12 years old | N/R | patients with T2D or obesity |

| Dutta [31] | depression and suicidality (as secondary outcome) | systematic review and meta-analysis | RCTs | 2 studies evaluating suicide risk | 7 (Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central, ctri.nic.in, clinicaltrials.gov, global health, and Google Scholar) | low risk of bias | 437 | N/R | N/R | patients with sleep obstruction apnoea |

| Ebrahimi [8] | suicide and self-harm | systematic review and meta-analysis | RCTs | 27 | 4 (MEDLINE, Embase, ClinicalTrials.gov, Cochrane) | Most were low risk; 5 high risk due to >5% attrition; and no publication bias detected | 59,403 participants (32,357 GLP-1; 27,046 placebo) | 59.5 years old | 56% males, 44% females | patients with diabetes or obseity |

| Pierret [9] | serious psychiatric disorders (major depression, suicidality, or psychosis), non-serious psychiatric disorders (anxiety or insomnia). | systematic review and meta-analysis | RCTs (Double-blind placebo-controlled trials) | 80 (only 3 assessing suicidality alone) | 4 (MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CENTRAL) | low risk of bias in 99% of studies | 107,860 | 60.1 years old | 40.1% females, 59.1% males | patients with diabetes or obseity |

| Silverii [17] | any psychiatric disorder or suicidal behaviors | meta-analysis | RCTs | 31 | 4 (Medline, Embase, Clinicaltrials.gov and Cochrane CENTRAL Database) | no evidence of publication bias | 84,713 | - | - | patients with diabetes or obseity |

| Strumila [26] | suicidal ideation and behaviors | narrative review | discussed studies included commentary, pharmacovigilance data (FAERS, EMA reports), real-world observational studies, and analogies with other interventions | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | obesity and diabetes |

| Valenta [10] | depression, anxiety, suicidality, alcohol and substance use disorders, binge eating disorder, psychosis, and autism spectrum disorders | scoping review | animal experiments, RCTs, cross-sectional and cohort studies, pharmacovigilance reports, and case reports/series | 81 total (51 animal, 30 human) | 2 (MEDLINE, Web of Science) | high quality | N/R | N/R | N/R | diabetes, obesity, psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety, substance use, binge eating, psychosis, and autism) for human studies |

| Valentino [32] | suicidality | systematic review | pharmacovigilance and cohort studies | 22 (10 pharmacovigilance,12 cohort) | 8 (Pubmed, Medline, Cochrane Library, PsychInfo, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science, Google Scholar) | cohort studies of moderate quality; pharmacovigilance studies were not assessed for quality | samples ranging from 204 to 131,255,418 | ranging from 0 to 85 years old | ranging from 53.18% to 65% females | N/R |

| Wei [25] | suicidality | meta-analysis | observational | 5 | 3 (PubMed, Embase, Scopus) | N/R | 746,306 | N/R | N/R | diabetes and obesity |

3.3. GLP-1RAs and Suicidality

3.4. GLP-1RAs and Other Psychological Effects

3.5. Quality Assessment of the Reviews

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

“(glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist OR GLP-1 receptor agonist) AND (suicide OR self-injury OR self-harm OR suicidal ideation OR suicidal behavior OR suicide attempt OR suicide risk) AND (diabetes) AND (review OR meta-analysis)”.

Appendix A.1. Inclusion Criteria

Appendix A.2. Exclusion Criteria

References

- GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Adult BMI Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence of adult overweight and obesity, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: A forecasting study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA Approves First Treatment to Reduce Risk of Serious Heart Problems Specifically in Adults with Obesity or Overweight. FDA Press Announcement, 8 March 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-reduce-risk-serious-heart-problems-specifically-adults-obesity-or (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Davies, M.; Færch, L.; Jeppesen, O.K.; Pakseresht, A.; Pedersen, S.D.; Perreault, L.; Rosenstock, J.; Shimomura, I.; Viljoen, A.; Wadden, T.A.; et al. Semaglutide 2.4 mg once a week in adults with overweight or obesity, and type 2 diabetes (STEP 2): A randomised, double-blind, obese-weight-loss trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 971–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiz, A.; Filion, K.B.; Tsoukas, M.A.; Yu, O.H.; Peters, T.M.; Eisenberg, M.J. Mechanisms of GLP-1 receptor agonist-induced weight loss: A review of central and peripheral pathways in appetite and energy regulation. Am. J. Med. 2025, 139, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wang, S.; Tang, H.; Yuan, T.; Zuo, W.; Liu, Y. Neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists: A pharmacovigilance analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Eur. Psychiatry 2025, 68, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Lei, X.; Fu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, Z. Efficacy and Safety of Tirzepatide, Dual GLP-1/GIP Receptor Agonists, in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi, P.; Batlle, J.C.; Ayati, A.; Maqsood, M.H.; Long, C.; Tarabanis, C.; McGowan, N.; Liebers, D.T.; Laynor, G.; Hosseini, K.; et al. Suicide and self-harm events with GLP-1 receptor agonists in adults with diabetes or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2025, 82, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierret, A.C.S.; Mizuno, Y.; Saunders, P.; Lim, E.; De Giorgi, R.; Howes, O.D.; McCutcheon, R.A.; McGowan, B.; Gupta, P.S.; Smith, D.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2025, 82, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenta, S.T.; Nicastri, A.; Perazza, F.; Marcolini, F.; Beghelli, V.; Atti, A.R.; Petroni, M.L. The impact of GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) on mental health: A systematic review. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 2024, 11, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Aranda, L.M.; Sanz-Matesanz, M.; Orozco-Durán, G.; González-Fernández, F.T.; Rodríguez-García, L.; Guadalupe-Grau, A. Effects of different rapid weight loss strategies and percentages on performance-related parameters in combat sports: An updated systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Statement on Ongoing Review of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-statement-ongoing-review-glp-1-receptor-agonists (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Silverii, G.A.; Marinelli, C.; Mannucci, E.; Rotella, F. GLP-1 receptor agonists and mental health: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 15538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, P.M.; Aroda, V.R.; Astrup, A.; Kushner, R.; Lau, D.C.W.; Wadden, T.A.; Brett, J.; Cancino, A.P.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Satiety and Clinical Adiposity—Liraglutide Evidence in individuals with and without diabetes (SCALE) study groups. Neuropsychiatric safety with liraglutide 3.0 mg. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2017, 19, 1529–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi-Sunyer, X.; Astrup, A.; Fujioka, K.; Greenway, F.; Halpern, A.; Krempf, M.; Lau, D.C.; le Roux, C.W.; Violante Ortiz, R.; Jensen, C.B.; et al. Liraglutide 30 mg for weight management: Arandomized controlled trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, K.; Ebrahimi, P.; Batlle, J.; Maqsood, M.H.; Ayati, A.; Long, C.; McGowan, N.; Tarabanis, C.; Laynor, G.; Heffron, S. Abstract 4139045: Suicide and Self-Harm with GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Circulation 2024, 150 (Suppl. 1), 4139045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverii, G.E.; Monami, M.; Mannucci, E. Antidepressant effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 31, 1368–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z. Exploring glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists as a potential disease-modifying agent in psychiatric and neurodevelopmental conditions: Evidence from a drug-target Mendelian randomization. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddit User. “Patients on GLP-1 RAs Exhibited a 195% Higher Risk of Major Depression, a 108% Increased Risk for Anxiety, and a 106% Elevated Risk for Suicidal Behavior. Data Source: TriNetX Database (2015–2023), Including 11.6 Million Patients with Obesity.” Reddit, r/Tirzepatidecompound, 9 Months Ago. Available online: https://www.reddit.com/r/tirzepatidecompound/comments/1hobfu8/patients_on_glp1_ras_exhibited_a_195_higher_risk (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI Data Extraction Form for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2014; Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- OpenAI ChatGPT [Large Language Model]; Version: July 2025; OpenAI: Bucharest, Romania, 2025; Available online: https://chat.openai.com/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Whiting, P.; Rutjes, A.W.; Reitsma, J.B.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Kleijnen, J. The development of QUADAS: A tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2003, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimized digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D. Association between GLP-1 receptor agonists and suicidal ideation in type 2 diabetes and obesity: A meta-analysis. Value Health 2024, 27, S605–S606. [Google Scholar]

- Strumila, R.; Lengvenyte, A.; Guillaume, S.; Nobile, B.; Olie, E.; Courtet, P. GLP-1 agonists and risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviours: Confound by indication once again? A narrative review. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024, 87, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso, F.L.; Estrin, M.A. Causal relationship between GLP-1 agonists and depressive symptomatology in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Salud Cienc. Tecnol.-Serie Conf. 2024, 3, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breit, S.; Hubl, D. The effect of GLP-1RAs on mental health and psychotropics-induced metabolic disorders: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2025, 176, 107415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushi, G.; Khatib, M.N.; Rohilla, S.; Singh, M.P.; Uniyal, N.; Ballal, S.; Bansal, P.; Bhopte, K.; Gupta, M.; Gaidhane, A.M.; et al. Association of GLP-1 receptor agonists with risk of suicidal ideation and behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2025, 41, e70037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, R.; Rindi, L.V.; Baldini, V.; Rossi, R.; Pacitti, F.; Jannini, E.A.; Rossi, A. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide and suicidal ideation and behavior: A systematic review of clinical studies and pharmacovigilance reports. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2025, 19, 103238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Jindal, R.; Raizada, N.; Nagendra, L.; Kamrul, H.A.; Sharma, M. Efficacy and safety of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonism based therapies in obstructive sleep apnoea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 29, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, K.; Teopiz, K.M.; Cheung, W.; Wong, S.; Le, G.H.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Mansur, R.B.; McIntyre, R.S. The effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on measures of suicidality: A systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 183, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.H.; Butts, A. Long-acting GLP-1RAs: An overview of efficacy, safety, and their role in type 2 diabetes management. JAAPA 2020, 33 (Suppl. 8), 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.M.; Tronieri, J.S.; Amaro, A.; Wadden, T.A. Semaglutide for the treatment of obesity. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 33, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neeland, I.J.; Linge, J.; Birkenfeld, A.L. Changes in lean body mass with glucagon-like peptide-1-based therapies and mitigation strategies. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26 (Suppl. 4), 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirvalidze, M.; Abbadi, A.; Dahlberg, L.; Sacco, L.B.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Morin, L. Estimating pairwise overlap in umbrella reviews: Considerations for using the corrected covered area (CCA) index methodology. Res. Synth. Methods 2023, 14, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, J.C.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Fox, K.R.; Bentley, K.H.; Kleiman, E.M.; Huang, X.; Musacchio, K.M.; Jaroszewski, A.C.; Chang, B.P.; Nock, M.K. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Treatment Duration | Reported Adverse Effects | Results Regarding Suicide | Other Psychological Effects | Effect Size (For Meta-Analyses) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barroso [27] | N/R | No | No causal effects on suicide behaviors were found. | Decreases in depressive symptoms were found. | N/A |

| Breit [28] | 4 weeks- 3 years | No | Mental illness samples: No effect on suicidality symptoms (four studies). Samples without mental illness: No effect on suicidality (one study, no other stud investigated suicidality). | Mental illness samples: No significant increase in psychiatric admissions (five studies), no significant effects on quality of life or functioning (two studies), improved psychopathology (two studies), no worsening effects on psychopathology (four studies), or reduction in alcohol use (two studies). Samples without mental illness: No effect on psychopathology (three studies), improved well-being (three studies), mental health (two studies), quality of life (eight studies), glycaemic control (one study), weight loss (two studies), treatment satisfaction (two studies), or reduced diabetes distress (two study). | N/A |

| Bushi [29] | N/R | No | The narrative analyses found that compared to other medications (eg., DPP-4 inhibitors), there was a lower risk of suicide attempts (three studies), no significant effects on suicidality (four studies), or no increase in suicidal ideation (one study). Compared with non-GLP-1RAs, results showed a lower risk of suicide attempts (one study) or no effect on suicidality (three studies). | N/R | A risk ratio quotient was pooled based on four studies. No significant results in suicidal outcomes between GLP-1RAs and other drug classes (RiskRatio = 0.568, 95% CI: 0.077–4.205); substantial uncertainty in the true effect (prediction interval, 0.001–218.938); high-heterogeneity (I2 = 98%, p < 0.01). |

| Di Stefano [30] | N/R | - | No effect on increasing suicide behavior. Although pharmacovigilance studies showed mixed effects (higher reporting rates compared to other antihyperglycemic agents), there was no causal effect. | N/R | N/A |

| Dutta [31] | N/R | - | Although the risk ratio analyses indicated a reduced tendency in suicidality for the experimental group, the effect was not significant | N/R | RiskRatio = 0.76 (95% CI: 0.07–7.96); p = 0.82; I2 = 33%. |

| Ebrahimi [8] | ≥6 months | - | No significant effect between the two groups on suicidality; no difference by diabetes status, or agent (liraglutide, semaglutide, etc.) either. | N/R | RiskRatio: 0.76; 95% CI, 0.48–1.21; p = 0.24; I2 = 0.0%. |

| Pierret [9] | 28 weeks | N/R | No significant results on suicidality (although only three studies assessed suicidality alone and an effect size could not be pooled for it). | No significant effects on serious, non-serious psychiatric disorders, or depression changes. Small improvements in eating restraint (g = 0.35), emotional eating (g = 0.32), and quality of life (mental-health-related, physical-health-related, diabetes-related, weight-related); g ranging from 0.15 to 0.27. | Serious psychiatric AE: logRiskRatio −0.02 (95% CI −0.20 to 0.17); non-serious: logRiskRatio −0.03 (95% CI −0.21 to 0.16); depression: g 0.02 (95% CI −0.51 to 0.55); eating restraint: g 0.35; and emotional eating: g 0.32. |

| Silverii [17] | 91 weeks | N/R | No significant effects on suicidality. | No significant effects on depression and anxiety. | The Mantel–Haenzel odds ratio (MH-OR) was used. MH-OR suicidality 95%, p = 0.61, I2 = 0%, MH-OR depression 95%, p = 0.82, I2 = 0%, MH-OR anxiety 95%, p = 0.66, I2 = 0%. |

| Strumila [26] | N/A | Potential risks related to rapid weight loss were as follows: allostatic load, catecholamine surge, serotonin restriction, endotoxemia, and psychological risks (unrealistic expectations and identity changes). | No significant effects on suicidality; a causal effect on suicidality was not supported. Bradford Hill criteria (strength of association, consistency, specificity, temporality, biological gradient, plausibility, coherence, experiment, and analogy) were not met. The association was weak, inconsistent, non-specific, and there was no proof related to a possible increase in suicidal ideation/behaviors after increasing the GLP-1RAs dose. However, a potential increase in suicidal ideation/behavior might follow after a failure of treatment meeting personal expectations. | Improvement in quality of life, decreased risk of anxiety disorders, or potential effectiveness on alcohol consumption (evidence in mice studies). | N/A |

| Valenta [10] | N/R | Some studies reported adverse effects such as depressive and anxious symptoms, while another study found nervousness, stress, eating disorders, insomnia, binge eating, fear of injection, fear of eating, and self-induced vomiting. | There were mixed results, as follows: – Animal/human studies suggest possible protective effects (reduced risk of suicidal ideation via anti-inflammatory/neuroprotective mechanisms). – Pharmacovigilance reports note cases of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, but causality is uncertain. | Potential effectiveness in improving depression and anxiety, cognition, alcohol/substance use, and binge eating. Mostly, there was an improvement trend for depression, cognition, and substance use, binge eating (in both animals and human studies). Mixed effects were found for anxiety (although protective in most contexts, anxiogenic in acute high-dose rodent models). Neutral/minimal effect for psychosis/autism (very limited evidence). | N/A |

| Valentino [32] | N/R | N/R | For cohort studies, results showed no evidence of an increase in suicidality. However, a reduced risk for suicidality in adolescents with obesity was reported in one study. Mixed results were found in pharmacovigilance, as follows: an increased risk was observed for semaglutide and liraglutide, whereas for the rest of the GLP-1RAs this trend was not supported. | N/R | |

| Wei 2024 [25] | N/R | N/R | Overall, a non-significant decreased trend in suicidal ideation was found. However, an increase in self-harm in those who were underweight was found to be significant. | N/R | Overall Risk Ratio: 0.83, p = 0.06. Risk ratio for underweight patients and self-injury: 1.05, p < 0.03. |

| Review | Quality |

|---|---|

| Barroso 2024 [27] | Moderate |

| Breit 2025 [28] | Moderate |

| Bushi 2025 [29] | Good |

| Di Stefano 2025 [30] | Moderate |

| Ebrahimi 2025 [8] | Good |

| Pierret 2025 [9] | Moderate |

| Silverii 2023 [17] | Poor |

| Valenta 2024 [10] | Moderate |

| Valentito 2025 [32] | Good |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ștefănescu, C.; Bratu, E.A.; Pelin, A.M.; Boroi, D.; Crecan-Suciu, B.D.; Ștefănescu, V. Evaluating Suicidal Risk in GLP-1RA Therapy: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analytic Evidence. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2958. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222958

Ștefănescu C, Bratu EA, Pelin AM, Boroi D, Crecan-Suciu BD, Ștefănescu V. Evaluating Suicidal Risk in GLP-1RA Therapy: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analytic Evidence. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2958. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222958

Chicago/Turabian StyleȘtefănescu, Cristina, Elena Alexandra Bratu, Ana Maria Pelin, Denisa Boroi, Bianca Daniela Crecan-Suciu, and Victorița Ștefănescu. 2025. "Evaluating Suicidal Risk in GLP-1RA Therapy: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analytic Evidence" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2958. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222958

APA StyleȘtefănescu, C., Bratu, E. A., Pelin, A. M., Boroi, D., Crecan-Suciu, B. D., & Ștefănescu, V. (2025). Evaluating Suicidal Risk in GLP-1RA Therapy: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analytic Evidence. Healthcare, 13(22), 2958. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222958