Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Alexithymia: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

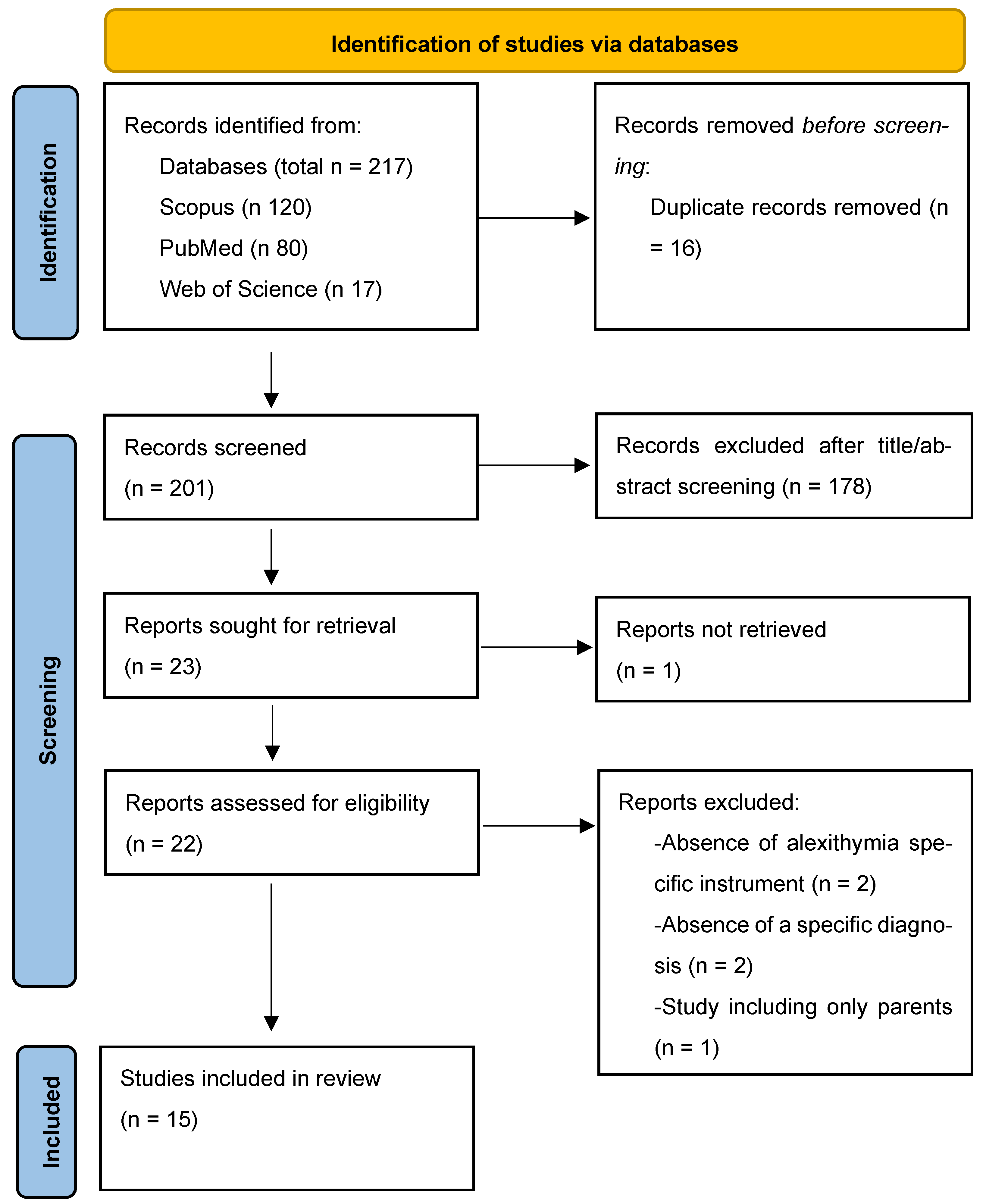

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Selection Process and Data Collection

2.4. Assessment of the Methodological Quality of the Finally Extracted Studies

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Weight and Risk for Obesity

3.3. Glycaemic Control

3.4. General Psychopathology

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| T1DM | Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

| T1M | Type 1 Diabetes |

| TAS-20 | Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20 |

| DIF | Difficulty Identifying Feelings |

| DDF | Difficulty Describing Feelings |

| EOT | Externally Oriented Thinking |

| CAM | Children’s Alexithymia Scale |

| AQC | Alexithymia Questionnaire for Children |

| HbA1 | Haemoglobin A1 |

| HbA1c | Haemoglobin A1c |

References

- Quattrin, T.; Mastrandrea, L.D.; Walker, L.S.K. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2023, 401, 2149–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazile, C.; Abdel Malik, M.M.; Ackeifi, C.; Anderson, R.L.; Beck, R.W.; Donath, M.Y.; Dutta, S.; Hedrick, J.A.; Karpen, S.R.; Kay, T.W.H.; et al. TNF-alpha inhibitors for type 1 diabetes: Exploring the path to a pivotal clinical trial. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1470677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrandrea, L.D.; Quattrin, T. Preventing type 1 diabetes development and preserving beta-cell function. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2022, 29, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, B.; Yang, W.; Xing, Y.; Lai, Y.; Shan, Z. Global, regional, and national burden of type 1 diabetes in adolescents and young adults. Pediatr. Res. 2025, 97, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomic, D.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, A.C. Type 1 diabetes mellitus: Much progress, many opportunities. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e142242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, G.; Di Giuseppe, M.; Silvestro, O.; Vicario, C.M.; Giorgianni, C.M.; Ruggeri, P.; Sparacino, G.; Juli, M.R.; Schwarz, P.; Lingiardi, V.; et al. Defense mechanisms in immune-mediated diseases: A cross-sectional study focusing on Severe Allergic Asthma and Hymenoptera Venom Anaphylaxis patients. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1608335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.; Vicario, C.M.; Cazzato, V.; Martino, G. Editorial: Psychological Factors as Determinants of Medical Conditions, Volume II. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 865235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conversano, C. Common Psychological Factors in Chronic Diseases. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, J.M.; Gnanasekaran, S.; Delahaye, J. Psychological aspects of chronic health conditions. Pediatr. Rev. 2012, 33, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.L.; Revenson, T.A.; Tennen, H. Health psychology: Psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 565–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyinnaya Calistus, J.; Joshua Oluwasegun, A.; Oluwaseun, I.; Lucy Oluebubechi, K.; Anjolaoluwa Joy, O.; Kaosara Temitope, A.; Mary Oluwasayo, T. Psychosocial factors in chronic disease management: Implications for health psychology. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 12, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L.; Dickinson, W.P. Psychology and primary care: New collaborations for providing effective care for adults with chronic health conditions. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeson, V.S.; Zajdel, M. Adjusting to Chronic Health Conditions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2017, 68, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestro, O.; Vicario, C.M.; Costa, L.; Sparacino, G.; Lund-Jacobsen, T.; Spatola, C.A.M.; Merlo, E.M.; Viola, A.; Giorgianni, C.M.; Catalano, A.; et al. Defense mechanisms and inflammatory bowel diseases: A narrative review. Res. Psychother. 2025, 28, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, E.M.; Myles, L.A.; Martino, G. On the Critical Nature of Psychosomatics in Clinical Practice. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 2025, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwesteeg, A.; Pouwer, F.; van der Kamp, R.; van Bakel, H.; Aanstoot, H.J.; Hartman, E. Quality of life of children with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2012, 8, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, B.; Roman-Urrestarazu, A. Health-related quality of life in paediatric patients with Type 1 diabetes mellitus using insulin infusion systems. A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novato Tde, S.; Grossi, S.A. Factors associated to the quality of life of adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2011, 45, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turin, A.; Drobnic Radobuljac, M. Psychosocial factors affecting the etiology and management of type 1 diabetes mellitus: A narrative review. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 1518–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, K.; Frazer, S.F.; Dempster, M.; Hamill, A.; Fleming, H.; McCorry, N.K. Psychological factors associated with diabetes self-management among adolescents with Type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1749–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, K.; Watad, A.; Coplan, L.; Amital, H.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Afek, A. Psychological stress and type 1 diabetes mellitus: What is the link? Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 14, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarizadeh, M.; Naderi Far, M.; Ghaljaei, F. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among children with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Pediatr. 2022, 18, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stene, L.C.; Norris, J.M.; Rewers, M.J. Risk factors for type 1 diabetes. In National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases Pamphlets (NIDDK); National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Bethesda, ML, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sivertsen, B.; Petrie, K.J.; Wilhelmsen-Langeland, A.; Hysing, M. Mental health in adolescents with Type 1 diabetes: Results from a large population-based study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2014, 14, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, F.; Langher, V.; Napoli, A.; Balonan, J.T.; Fedele, F.; Martino, G.; Amorosi, F.R.; Caputo, A. Unconscious loss processing in diabetes: Associations with medication adherence and quality of care. Psychoanal. Psychother. 2021, 35, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, G.; Bellone, F.; Langher, V.; Caputo, A.; Catalano, A.; Quattropani, M.C.; Morabito, N. Alexithymia and psychological distress affect perceived quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroianu, L.A.; Motofei, I.G.; Cecilia, C.; Barbu, R.E.; Toma, A. The impact of anxiety and depression on the pediatric patients with diabetes. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pușcașu, A.; Bolocan, A.; Păduraru, D.N.; Salmen, T.; Bica, C.; Andronic, O. The implications of chronic psychological stress in the development of diabetes mellitus type 2. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ademoyegun, A.B.; Afolabi, O.E.; Aghedo, I.A.; Adelowokan, O.I.; Mbada, C.E.; Awotidebe, T.O. The mediating role of sedentary behaviour in the relationship between social support and depression among individuals with diabetes. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 10, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrosso, D.M.F.; Primavera, M.; Samvelyan, S.; Tagi, V.M.; Chiarelli, F. Stress and Diabetes Mellitus: Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Clinical Outcome. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2023, 96, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilou, P.; Vlastos, D.D. The Psychological Burden of Families with Diabetic Children: A Literature Review Focusing on Quality of Life and Stress. Children 2023, 10, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondek, T.M.; Kiejna, A.; Cichoń, E.; Kokoszka, A.; Bobrov, A.; de Girolamo, G.; Lecic-Tosevski, D.; Mankovsky, B.; Müssig, K.; Wölwer, W. Anxiety disorders as predictors of suicidality in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Findings of a study in six European countries. Psychiatr. Pol. 2024, 58, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukasiewicz, A.; Kiejna, A.; Cichoń, E.; Jodko-Modlińska, A.; Obrębski, M.; Kokoszka, A. Relations of well-being, coping styles, perception of self-influence on the diabetes course and sociodemographic characteristics with HbA1c and BMI among people with advanced type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukasiewicz, A.; Cichoń, E.; Kostecka, B.; Kiejna, A.; Jodko-Modlińska, A.; Obrębski, M.; Kokoszka, A. Association of higher rates of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) complications with psychological and demographic variables: Results of a cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 3303–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, C.; Sartorius, N.; Ahmed, H.; Alvarez, A.; Bahendeka, S.; Bobrov, A.; Burti, L.; Chaturvedi, S.; Gaebel, W.; De Girolamo, G. Factors associated with the onset of major depressive disorder in adults with type 2 diabetes living in 12 different countries: Results from the INTERPRET-DD prospective study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarrasa, N.; San Jose, P.; Rubio, M.A.; Lecube, A. Obesity in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes: Links, Risks and Management Challenges. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 2807–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Schueren, B.; Ellis, D.; Faradji, R.N.; Al-Ozairi, E.; Rosen, J.; Mathieu, C. Obesity in people living with type 1 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Frank, P. Obesity and psychological distress. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20220225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Portilla Maya, S.R.; de la Portilla Maya, D.A.; Londoño, D.M.M.; Martínez, D.A.L. Association Between Obesity, Executive Functions, and Affective States: An Analysis of Patients from an Endocrinology Clinic. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2025, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batt, E.; Asif-Malik, A. A narrative review of the current literature into the impacts of fasting on levels of impulsivity and psychological stress. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2025, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klanduchova, E.; Adamovska, L. Emotion and Stress Related Eating and Personality Dimensions Predict Food Addiction: Implications for Personalized Weight Management and Primary Prevention. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2025, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucifora, C.; Martino, G.; Grasso, G.; Mucciardi, M.; Magnano, P.; Massimino, S.; Craparo, G.; Vicario, C.M. Does Fasting Make Us All Equal? Evidence on the Influence of Appetite on Implicit Sexual Prejudice. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2025, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar, A.; Oza, C. Glycaemic Control in Youth and Young Adults: Challenges and Solutions. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2022, 15, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitew, Z.W.; Alemu, A.; Jember, D.A.; Tadesse, E.; Getaneh, F.B.; Sied, A.; Weldeyonnes, M. Prevalence of Glycemic Control and Factors Associated With Poor Glycemic Control: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Inquiry 2023, 60, 469580231155716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, T.; Morrissey, H.; Ball, P. Systematic Review of Psychological and Educational Interventions Used to Improving Adherence in Diabetes and Depression Patients. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, D.A.; Gross, J.J. Conceptualizing alexithymia. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2023, 215, 112375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, I.M. A review of the alexithymia concept. Psychosom. Med. 1981, 43, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoney, L.R.; Holder, M.D.; Timoney, L.R.; Holder, M.D. Definition of alexithymia. In Emotional Processing Deficits and Happiness: Assessing the Measurement, Correlates, and Well-Being of People with Alexithymia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.J. Alexithymia: 25 years of theory and research. In Emotional Expression and Health: Advances in Theory, Assessment and Clinical Applications; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2004; pp. 137–153. [Google Scholar]

- Martino, G.; Caputo, A.; Vicario, C.M.; Catalano, A.; Schwarz, P.; Quattropani, M.C. The Relationship Between Alexithymia and Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.H.; Wei, Y.T.; Tao, H.X.; Yang, Q.X.; Zhang, G.L.; Guo, X.J.; Guo, J.L.; Yan, F.H.; HanPh, D.L. The prevalence and characteristics of alexithymia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2022, 162, 111018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestro, O.; Ricciardi, L.; Catalano, A.; Vicario, C.M.; Tomaiuolo, F.; Pioggia, G.; Squadrito, G.; Schwarz, P.; Gangemi, S.; Martino, G. Alexithymia and asthma: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1221648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, M.A.; Beyer, J.; Radcliffe, A. Alexithymia and physical health problems: A critique of potential pathways and a research agenda. In Emotion Regulation: Conceptual and Clinical Issues; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, M.A.; Stettner, L.; Wehmer, F. How are alexithymia and physical illness linked? A review and critique of pathways. J. Psychosom. Res. 1996, 41, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, M. Alexithymia as a prognostic risk factor for health problems: A brief review of epidemiological studies. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2012, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kano, M.; Fukudo, S. The alexithymic brain: The neural pathways linking alexithymia to physical disorders. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2013, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luminet, O.; Nielson, K.A. Alexithymia: Toward an Experimental, Processual Affective Science with Effective Interventions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2025, 76, 741–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangemi, S.; Ricciardi, L.; Caputo, A.; Giorgianni, C.; Furci, F.; Spatari, G.; Martino, G. Alexithymia in an unconventional sample of Forestry Officers: A clinical psychological study with surprising results. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, L.; Spatari, G.; Vicario, C.M.; Liotta, M.; Cazzato, V.; Gangemi, S.; Martino, G. Clinical Psychology and Clinical Immunology: Is there a link between Alexithymia and severe Asthma? Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuseppe, M.; Conversano, C. Psychological components of chronic diseases: The link between defense mechanisms and alexithymia. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgianni, C.M.; Martino, G.; Brunetto, S.; Buta, F.; Lund-Jacobsen, T.; Tonacci, A.; Gangemi, S.; Ricciardi, L. Allergic Sensitization and psychosomatic involvement in outdoor and indoor workers: A preliminary and explorative survey of motorway toll collectors and office employees. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, A.; Alamrawy, R.; Ramadan, I.; Elmissiry, M. Alexithymia among patients with unexplained physical symptoms. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, S249–S250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubaki, K.; Shimizu, E. Psychological Treatments for Alexithymia: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luminet, O.; Bagby, R.M.; Taylor, G.J. Alexithymia: Advances in Research, Theory, and Clinical Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Concha, N.; Arancibia, M.; Salas, F.; Behar, R.; Salas, G.; Silva, H.; Escobar, R. Towards a neurobiological understanding of alexithymia. Medwave 2017, 17, e6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, M.A.; Neely, L.C.; Burger, A.J. The assessment of alexithymia in medical settings: Implications for understanding and treating health problems. J. Personal. Assess. 2007, 89, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donges, U.-S.; Suslow, T. Alexithymia and automatic processing of emotional stimuli: A systematic review. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 28, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayiotou, G.; Panteli, M.; Vlemincx, E. Adaptive and maladaptive emotion processing and regulation, and the case of alexithymia. Cogn. Emot. 2021, 35, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.K.; Hasaballa, E.I.; Abdalla, A.A.; Refaee, A.; Nofal, M.; Shaban, M.; Abdurrahman, E.A.M.; Shehata, S.; Alsaied, R. Relationship between sleep disturbances, alexithymia, psychiatric problems, and clinical variables in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2024, 31, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzi, L.; Bitsios, P.; Solidaki, E.; Christou, I.; Kyrlaki, E.; Sfakianaki, M.; Kogevinas, M.; Kefalogiannis, N.; Pappas, A. Type 1 diabetes is associated with alexithymia in nondepressed, non-mentally ill diabetic patients: A case-control study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 67, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housiaux, M.; Luminet, O.; Van Broeck, N.; Dorchy, H. Alexithymia is associated with glycaemic control of children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2010, 36, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luminet, O.; de Timary, P.; Buysschaert, M.; Luts, A. The role of alexithymia factors in glucose control of persons with type 1 diabetes: A pilot study. Diabetes Metab. 2006, 32, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, E.O.; Thunander, M.; Svensson, R.; Landin-Olsson, M.; Thulesius, H.O. Depression, obesity, and smoking were independently associated with inadequate glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 168, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, E.O.; Svensson, R.; Thunander, M.; Hillman, M.; Thulesius, H.O.; Landin-Olsson, M. Gender, alexithymia and physical inactivity associated with abdominal obesity in type 1 diabetes mellitus: A cross sectional study at a secondary care hospital diabetes clinic. BMC Obes. 2017, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melin, E.O.; Thunander, M.; Landin-Olsson, M.; Hillman, M.; Thulesius, H.O. Depression differed by midnight cortisol secretion, alexithymia and anxiety between diabetes types: A cross sectional comparison. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melin, E.O.; Hillman, M.; Thunander, M.; Landin-Olsson, M. Midnight salivary cortisol secretion and the use of antidepressants were associated with abdominal obesity in women with type 1 diabetes: A cross sectional study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melin, E.O.; Svensson, R.; Dereke, J.; Hillman, M. Galectin-3 Binding Protein, Depression, and Younger Age Were Independently Associated With Alexithymia in Adult Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 672931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, E.M.; Tutino, R.; Myles, L.A.M.; Lia, M.C.; Minasi, D. Alexithymia, intolerance to uncertainty and mental health difficulties in adolescents with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, E.M.; Tutino, R.; Myles, L.A.M.; Alibrandi, A.; Lia, M.C.; Minasi, D. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, Psychopathology, Uncertainty and Alexithymia: A Clinical and Differential Exploratory Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnif, L.; Damak, R.; Mnif, F.; Ouanes, S.; Abid, M.; Jaoua, A.; Masmoudi, J. Alexithymia impact on type 1 and type 2 diabetes: A case-control study. Ann. Endocrinol. 2014, 75, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, A.; Nwokolo, M.; Smith, E.L.; de Zoysa, N.; Garrett, C.; Choudhary, P.; Amiel, S.A. Personality traits of alexithymia and perfectionism in impaired awareness of hypoglycemia in adults with type 1 diabetes—An exploratory study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 150, 110634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelizza, L.; Pupo, S. Alexithymia in adults with brittle type 1 diabetes. Acta Biomed. 2019, 90, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayeghian, Z.; Moeineslam, M.; Hajati, E.; Karimi, M.; Amirshekari, G.; Amiri, P. The relation of alexithymia and attachment with type 1 diabetes management in adolescents: A gender-specific analysis. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutari, C.; DeMarsilis, A.; Mantzoros, C.S. Obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 202, 110773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, S.; Gastaldelli, A.; Yki-Jarvinen, H.; Scherer, P.E. Why does obesity cause diabetes? Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohm, T.V.; Meier, D.T.; Olefsky, J.M.; Donath, M.Y. Inflammation in obesity, diabetes, and related disorders. Immunity 2022, 55, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giandalia, A.; Russo, G.T.; Ruggeri, P.; Giancaterini, A.; Brun, E.; Cristofaro, M.; Bogazzi, A.; Rossi, M.C.; Lucisano, G.; Rocca, A. The burden of obesity in type 1 diabetic subjects: A sex-specific analysis from the AMD annals initiative. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, e1224–e1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kueh, M.T.; Chew, N.W.; Al-Ozairi, E.; le Roux, C.W. The emergence of obesity in type 1 diabetes. Int. J. Obes. 2024, 48, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, F.Z. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, ITC33–ITC48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanton, S.; Azevedo, L.C.; Vargas, D.M. Alexithymia in obese adolescents is associated with severe obesity and binge eating behavior. J. Pediatr. 2022, 98, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karukivi, M.; Jula, A.; Hutri-Kahonen, N.; Juonala, M.; Raitakari, O. Is alexithymia associated with metabolic syndrome? A study in a healthy adult population. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 236, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu, Z.; Kadak, M.T.; Tarakcioglu, M.C.; Bingol Caglayan, R.H.; Dogangun, B.; Ercan, O. Eating behaviors and alexithymic features of obese and overweight adolescents. Pediatr. Int. 2022, 64, e15008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimoradi, Z.; Majd, N.R.; Brostrom, A.; Tsang, H.W.H.; Singh, P.; Ohayon, M.M.; Lin, C.Y.; Pakpour, A.H. Is alexithymia associated with sleep problems? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 133, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, C.; Di Francesco, G.; Severo, M.; Lanzara, R.; Richards, K.; Guagnano, M.T.; Porcelli, P. Alexithymia and metabolic syndrome: The mediating role of binge eating. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.J.; Wang, W.; Lim, S.T.; Wu, V.X. Factors associated with glycaemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic literature review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 1433–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, J.A.; Wild, S.H.; Lamb, M.J.; Cooper, M.N.; Jones, T.W.; Davis, E.A.; Hofer, S.; Fritsch, M.; Schober, E.; Svensson, J.; et al. Glycaemic control of Type 1 diabetes in clinical practice early in the 21st century: An international comparison. Diabet. Med. 2015, 32, 1036–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, B.A.; Sherr, J.L.; Mathieu, C. Type 1 diabetes glycemic management: Insulin therapy, glucose monitoring, and automation. Science 2021, 373, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.; Pereira, B.; Patton, S.R.; Brandao, T. Parental Psychosocial Variables and Glycemic Control in T1D Pediatric Age: A Systematic Review. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2024, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franc, S.; Charpentier, G. Emotional distress as a therapeutic target against persistent poor glycaemic control in subjects with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 4662–4673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, P.D.; Karantzas, G.C.; Faustino, B.; Pizarro-Campagna, E. Early maladaptive schemas, emotion regulation difficulties and alexithymia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2024, 31, e2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, A.S.; Khawaja, S.; Naguib, M. ‘Diabulimia’: Current insights into type 1 diabetes and bulimia nervosa. Prog. Neurol. Psychiatry 2023, 27, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabe, H.J.; Spitzer, C.; Freyberger, H.J. Alexithymia and personality in relation to dimensions of psychopathology. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1299–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, L.; Haddock, G.; Shaw, J.; Pratt, D. Alexithymia and Its Associations With Depression, Suicidality, and Aggression: An Overview of the Literature. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar, R.; Talwar, S.; Desai, G.; Chaturvedi, S.K. Relationship between alexithymia and depression: A narrative review. Indian. J. Psychiatry 2021, 63, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G.J.; Bagby, R.M. New trends in alexithymia research. Psychother. Psychosom. 2004, 73, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deniz-Garcia, A.; Diaz-Artiles, A.; Saavedra, P.; Alvarado-Martel, D.; Wagner, A.M.; Boronat, M. Impact of anxiety, depression and disease-related distress on long-term glycaemic variability among subjects with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas Moreno, V.; Sager La Ganga, C.; Tapia Sanchiz, M.S.; Lopez Ruano, M.; Del Carmen Martinez Otero, M.; Carrillo Lopez, E.; Raposo Lopez, J.J.; Amar, S.; Gonzalez Castanar, S.; Marazuela, M.; et al. Impact of psychiatric disorders on the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis in adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus: A propensity score matching case-control study. Endocrine 2025, 88, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiardini, I.; Abba, S.; Ballauri, M.; Vuillermoz, G.; Braido, F. Alexithymia and chronic diseases: The state of the art. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2011, 33, A47–A52. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.; Wu, Y.; Peng, L.; Chen, S.; Yuan, J.; Wang, W.; Cong, L. Constructing and Verifying an Alexithymia Risk-Prediction Model for Older Adults with Chronic Diseases Living in Nursing Homes: A Cross-Sectional Study in China. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, B.; Freni, F.; Meduri, A.; Oliverio, G.W.; Signorino, G.A.; Perroni, P.; Galletti, C.; Aragona, P.; Galletti, F. Rhi-no-Orbito-Cerebral Mucormycosis in Diabetic Disease Mucormycosis in Diabetic Disease. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2020, 31, e321–e324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliverio, G.W.; Meduri, A.; De Salvo, G.; Trombetta, L.; Aragona, P. OCT Angiography Features in Diabetes Mellitus Type 1 and 2. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Term |

|---|---|

| 1 | ALEXITHYMI * [all fields] |

| 2 | ALEXITHYMIA [all fields] |

| 3 | TYPE 1 DIABETES MELLITUS [all fields] |

| 4 | T1DM [all fields] |

| 5 | T1D [all fields] |

| 6 | 2 AND 3 OR 4 OR 5 |

| 7 | 1 AND 6 |

| Authors | Year | Study Design | State | Sample | Alexithymia Measure | Findings | NIH Study Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al. [73] | 2024 | Cross-sectional | Egypt | 118 T1DM patients | Children’s Alexithymia Measure (CAM) | Alexithymia was associated with sleep difficulties. Higher alexithymia scores (β = 0.187, p = 0.033) and elevated BMI (β = 0.257, p = 0.005) independently predicted sleep difficulties. CAM scores were higher in subjects suffering from sleep disorders. | Good |

| Chatzi et al. [74] | 2009 | Case–control study | Greece | 96 T1DM patients and 105 health controls | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20). | Higher rates of alexithymia were found in T1DM patients (22.2% vs. 7.6%). Trend-level associations were observed between alexithymia and longer diabetes duration, as well as reduced treatment intensity. | Fair |

| Housiaux et al. [75] | 2010 | Cross-sectional | Belgium | 45 T1DM patients | Alexithymia Questionnaire for Children (AQC) | Higher DDF score significantly predict poorer glycaemic control in children with T1DM (β = 0.34; p = 0.01), accounting 12% of variance. Alexithymia was also associated with disease severity, even though further studies were necessary to confirm data. | Good |

| Luminet et al. [76] | 2006 | Longitudinal study | Belgium | 64 T1DM patients | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | Difficulty describing feelings (DDF) predicted lower glucose control. Its role overcomes the predictive power of anxiety and depression. Data were stable along T1DM and T2DM, configuring DDF as a strong predictor worsening disease. Alexithymia total score indexes changed between T1 and T2 (46.44 ± 10.86 vs. 35.64 ± 14.03). | Good |

| Melin et al. [77] | 2013 | Cross-sectional study | Sweden | 292 T1DM patients | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | Alexithymia was associated with lower glycaemic control and depression in bivariate analyses. Only symptoms of depression independently predicted glycaemic control in T1DM patients (AOR = 4.8, p = 0.001; AOR = 19.8, p < 0.001 in women). | Good |

| Melin et al. [78] | 2017 | Cross-sectional study | Sweden | 284 T1DM patients | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | Alexithymia and its subdimension DIF were associated with abdominal obesity (p = 0.028; p = 0.011). Stratified analysis revealed that the association between difficulty identifying feelings and central adiposity was notably stronger in male patients (p = 0.004). In women, abdominal obesity was linked to antidepressant use and physical inactivity (p = 0.022 and p = 0.037). | Good |

| Melin et al. [79] | 2017 | Cross-sectional study | Sweden | 148 T1DM patients and 24 T2DM patients | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | T1DM and T2DM differed in terms of alexithymia associations with depression and anxiety. Alexithymia was associated with depression in T2DM patients (67% vs. 11%), while T1DM patients presented lower scores of alexithymia (47% vs. 11%). | Good |

| Melin et al. [80] | 2019 | Cross-sectional study | Sweden | 190 T1DM patients | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | Alexithymia was associated with abdominal obesity in men (p = 0.018). As a concrete risk factor, alexithymia was the only demonstrated feature strongly influencing abdominal obesity in men with T1DM. | Good |

| Melin et al. [81] | 2021 | Cross-sectional study | Sweden | 292 T1DM patients | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | T1DM patients with alexithymia (15%) had 5.7 times higher prevalence of depression, twice as high prevalence of anxiety, 1.9 times higher prevalence of abdominal obesity, and 3.2 times higher prevalence of combined anxiety and abdominal obesity compared to patients without alexithymia. Elevated levels of Galectin-3 Binding Protein (Gal3BP) were also 2.3 times more frequent among alexithymic patients. | Good |

| Merlo et al. [82] | 2024 | Cross-sectional study | Italy | 137 T1DM patients | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | Alexithymia emerged as significant for T1DM patients (total score = 53.766 ± 11.907). Alexithymia was associated with different extents to depression, anxiety, obsession eating disorders and somatisation. Thus, a clear positive relationship emerged between alexithymia and intolerance to uncertainty. Moreover, age predicted greater rates of externally oriented thinking, and female gender predicted greater difficulty identifying feelings. | Good |

| Merlo et al. [83] | 2024 | Cross-sectional study | Italy | 105 T1DM patients | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | A concerning presence of alexithymia was highlighted in T1DM patients (total score = 54.67 ± 12.35). Age, education and illness duration were negatively associated with psychopathology. Alexithymia and intolerance to uncertainty were positively associated. Externally oriented thinking and inhibitory anxiety significantly differed among male and female patients aged 14 to 18 years, with higher scores in male subjects. | Good |

| Mnif et al. [84] | 2014 | Cross-sectional study | Tunisia | 50 T1DM patients, 75 T2DM patients and 122 healthy controls. | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | T1DM showed higher alexithymia prevalence compared to healthy controls (46% vs. 21.5%). Alexithymic patients had significantly higher fasting glucose levels and a greater incidence of complications (21.7% vs. 14.8%). Erectile dysfunction was associated with DIF (p = 0.012), while EOT was linked to irregular follow-up and poor treatment adherence (p = 0.032). Depression emerged as significant predictor of alexithymia, which also showed positive correlations with anxiety (p = 0.008) and depression scores (p = 0.003). | Fair |

| Naito et al. [85] | 2021 | Cross-sectional study | United Kingdom | 90 T1DM patients | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | Alexithymia positively correlated with cognitive barriers related to Hyperglycaemia Avoidance Prioritised and Asymptomatic Hypoglycaemia Normalised. High alexithymia scores were found in patients with impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia (17.6% vs. 1.9%). These findings highlight alexithymia as a psychological trait linked to risk factors for hypoglycaemia and impaired self-management. | Good |

| Pelizza & Pupo [86] | 2019 | Cross-sectional study | Italy | 44 Brittle T1DM and 88 T1DM patients | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | Patients suffering from a brittle form of T1DM were more alexithymic than controls (18.2% vs. 2.3%). Alexithymia was significantly associated with anxiety, obsession, depression, paranoid ideation, somatisation and psychoticism. Obsessive–compulsive traits (β = 0.44, t = 3.19, p < 0.01) and somatisation (β = 0.59, t = 4.76, p < 0.05) emerged as independent predictors of alexithymia. | Good |

| Shayeghian et al. [87] | 2020 | Cross-sectional study | Iran | 150 T1DM patients | Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) | Alexithymia, and, in particular, DIF predicted poorer disease management in both female (β = −0.04, p = 0.02; β = −0.06, p = 0.04) and male patients (β = −0.07, p = 0.01; β = −0.11, p = 0.01). DDF predicted poorer self-management only in males (β = −0.16, p = 0.02), while in females, alexithymia and DIF were associated with HbA1c levels (β = 0.15, p = 0.03). Alexithymia can affect self-management for both male and female subjects suffering from T1DM. | Good |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Merlo, E.M.; Myles, L.A.M.; Silvestro, O.; Ruggeri, D.; Russo, G.T.; Squadrito, G.; Martino, G. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Alexithymia: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192402

Merlo EM, Myles LAM, Silvestro O, Ruggeri D, Russo GT, Squadrito G, Martino G. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Alexithymia: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192402

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerlo, Emanuele Maria, Liam Alexander MacKenzie Myles, Orlando Silvestro, Domenica Ruggeri, Giuseppina Tiziana Russo, Giovanni Squadrito, and Gabriella Martino. 2025. "Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Alexithymia: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192402

APA StyleMerlo, E. M., Myles, L. A. M., Silvestro, O., Ruggeri, D., Russo, G. T., Squadrito, G., & Martino, G. (2025). Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus and Alexithymia: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(19), 2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192402