Psychological Interventions for the Treatment of Patients with Chronic Dermatoses: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

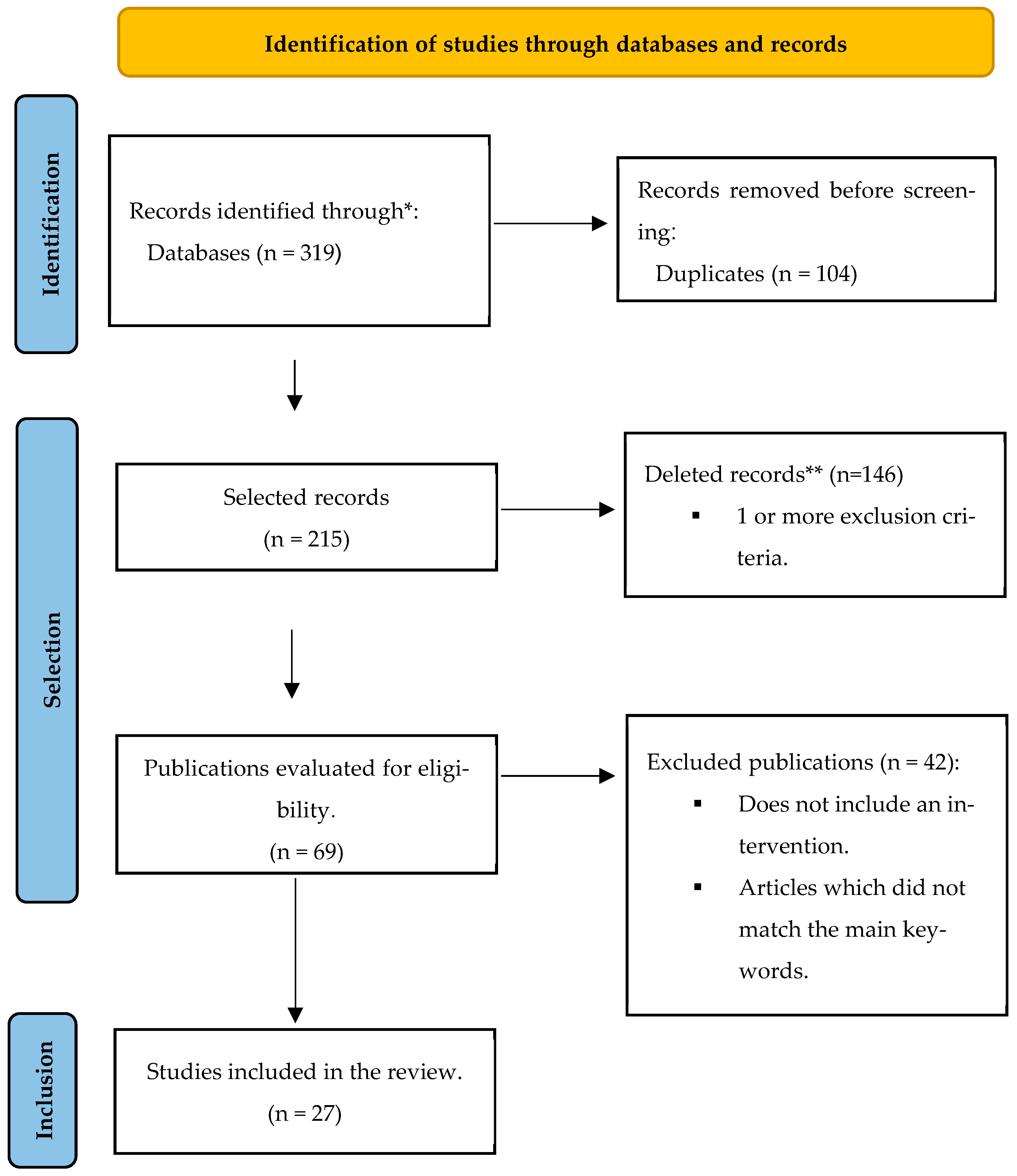

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Screening

2.5. Quality Assessment

| Authors | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | % Yes | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Adkins, 2021) [15] | Y | U | Y | U | NA | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 69.2 | Moderate |

| (Kelly et al., 2009) [16] | Y | U | Y | N | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 69.2 | Moderate |

| (D’Alton et al., 2019b) [17] | Y | U | N | N | U | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | 53.8 | Moderate |

| (Singh et al., 2017) [18] | Y | U | U | N | U | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 61.5 | Moderate |

| (Larsen et al., 2014b) [19] | Y | U | U | N | U | U | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | 53.8 | Moderate |

| (Kishimoto et al., 2023) [20] | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 84.6 | Low |

| (Hudson et al., 2020) [21] | Y | U | U | N | N | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 53.8 | Moderate |

| (Mifsud et al., 2021b) [22] | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 92.3 | Low |

| (Muftin et al., 2022) [23] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 92.3 | Low |

| (Łakuta, 2022) [24] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 | Low |

| (Seekis et al., 2017b) [1] | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 84.6 | Low |

| (Sengupta et al., 2025) [25] | Y | U | U | N | N | U | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 53.8 | Moderate |

| (Sherman et al., 2019) [26] | Y | U | Y | Y | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 76.9 | Low |

| (Borimnejad et al., 2015) [27] | Y | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 76.9 | Low |

| (Bundy et al., 2013) [28] | Y | U | Y | U | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 69.2 | Moderate |

| (Pascual-Sánchez et al., 2020) [29] | Y | U | Y | N | NA | U | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 61.5 | Moderate |

| Authors | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | % Yes | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Hedman-Lagerlöf et al., 2019) [30] | Y | N | NA | NA | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | 55 | Moderate |

| (Offenbächer et al., 2021) [31] | Y | N | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 66.6 | Moderate |

| (Harfensteller, 2022) [32] | Y | N | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 66.6 | Moderate |

| (Ridge et al., 2021) [33] | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | 77.7 | Low |

| (Latifi et al., 2020) [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 | Low |

| (Li et al., 2020) [35] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | 88.8 | Low |

| Authors | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | % Yes | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Da Silva et al., 2011) [36] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 | Low |

| (Zucchelli et al., 2021) [37] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | 90 | Low |

| Authors | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | % Yes | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Bartholomew et al., 2022) [38] | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 72.7 | Moderate |

| (Rafidi et al., 2022) [39] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | N | Y | Y | 72.7 | Moderate |

| Authors | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | % Yes | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Yosipovitch et al., 2024) [8] | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | 83.3 | Low |

3. Results

3.1. Studies’ Characteristics

3.2. Studies’ Results Summary

| Reference | Analysis and Statistical Methods | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| (Adkins, 2021) [15] | ANCOVA; Cronbach’s alphas | Age; gender; ethnicity, educational; dermatological condition that affects their body image; language |

| (Ahmed et al., 2018) [9] | Independent t-tests | People with vitiligo; age (>18) |

| (Bartholomew et al., 2022) [38] | Qualitative synthesis | Type of intervention; psoriasis; Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; Dermatology Life Quality Index; Perceived stress |

| (Borimnejad et al., 2015) [27] | Student’s t-tests; | Age; diagnosis of vitiligo confirmed; ability to read and write |

| (Bundy et al., 2013) [28] | Analise of covariance (ANCOVA), intention-to treat (ITT), multiple imputation, multivariate logistic regression, Shapiro–Wilk test, Stata v12 | |

| (Clarke et al., 2020b) [3] | SPSS 26; multiple regression; bivariate correlations; independent t-tests | Dermatology patients; age; gender; ethnicity; employment status; marital status; education level |

| (D’Alton et al., 2019b) [17] | Not discriminated | Age; diagnosis of psoriasis; systemic medication for 6 months or more |

| (Da Silva et al., 2011) [36] | Not discriminated | People with psychodermatoses; age; gender |

| (Galhardo et al., 2022) [7] | SPSS, v. 27; Pearson’s correlation; hierarchical multiple linear regression; Durbin–Watson statistics; | People with a diagnosis of psoriasis; age; gender |

| (Harfensteller, 2022) [32] | Spearman’s correlation coefficient; SPSS IBM 26; t-tests; Cohen’s d; | Patients with diagnosed Atopic dermatitis (AD); age (18–65); language |

| (Hedman-Lagerlöf et al., 2019) [30] | STATA version 14.2; t-tests; | Age (18–65); adults with Atopic dermatitis; duration of AD for at least 6 months; language |

| (Hewitt et al., 2022) [41] | NVivo 12 Pro; | Age; self-diagnosed dermatological condition |

| (Hudson et al., 2020) [21] | Independent samples t-tests; chi square tests | Age (16); English-speaking; diagnosis of a skin condition; |

| (Hughes et al., 2023) [42] | Thematic analysis | 8–11 years of age; diagnosed with any skin condition and English-language speakers; eligible parents were 18 years of age or over; the child’s main caregiver |

| (Kelly et al., 2009) [16] | ANOVAs; | Age; facial acne; prescribed acne treatment perceived to be ineffective |

| (Kishimoto et al., 2023) [20] | Mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM), adjusting for age, sex, and baseline DLQI, to assess within- and between-group differences. Additional DLQI analyses included: (1) percentage of patients with >4-point improvement, (2) subgroup analysis by sex, age, and baseline DLQI, and (3) per-protocol comparisons. All analyses used SAS 9.4 with standard corrections | Age, sex, education, marital status, living situation, working situation Disease duration, dermatologic treatment |

| (Łakuta, 2022) [24] | Six linear mixed models (LMMs); PROCESS macro version 3.5.3; | Age; physician-diagnosed psoriasis |

| (Larsen et al., 2014b) [19] | SPSS version 19; t-tests; qui 2 statistics, or Mann–Whitney U tests; ANOVA; Cohen’s d; ANCOVAs; | Age; gender; educational level; health status; disease duration |

| (Latifi et al., 2020) [34] | Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (repeated-measures ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis test) | Women with skin cancer; age; children; education. Checklist of physiological symptoms related to skin cancer: skin changes, unreasonable weight loss, bloating, change in the chest, abnormal bleeding, trouble with swallowing, blood in the stool, abdominal pain, depression, mouth infections, persistent and unspecified pain, changes in lymph nodes, fever, fatigue, persistent cough, and indigestion. Three scales (severe, partial, and never) to assess the symptoms, and patients reported changes and a lack of changes in their status. |

| (Li et al., 2020) [35] | SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 17.0. Student’s t-tests and the chi-square tests; hospitalization length and patient satisfaction between the different groups. | Age, gender, mean time from diagnosis to treatment initiation, and family history of psoriasis |

| (Melissant et al., 2021b) [12] | SPSS version 26; Multiple regression model; Linear mixed; | Head and neck cancer (HNC) survivors |

| (Mifsud et al., 2021b) [22] | c2 tests of Independence; ANOVA; chi-square tests; Shapiro–Wilk’s; Levene’s Test of Homogeneity of Variance; SPSS version 23; | Age; gender; diagnosed with stage I to III breast cancer, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and/or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS); experienced at least one negative event related to the changes that have occurred to their body after breast cancer; language |

| (Muftin et al., 2022) [23] | SPSS Statistics; intention-to-treat (ITT); v2-tests; MANOVA; ANOVA; | Gender; age; ethnicity; education |

| (Offenbächer et al., 2021) [31] | SPSS; t-test; per-protocol analysis (PPA); | Age; diagnosis of AD; |

| (Pascual-Sánchez et al., 2020) [29] | IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 21.0; t-test for independent sample; Pearson correlation | Women with AAU; age; time of disease; number of received treatments |

| (Rafidi et al., 2022) [39] | Qualitative synthesis | Type of intervention; dermatologic disease; treatment outcomes |

| (Ridge et al., 2021) [33] | GraphPad Prism software; version 9.3.1. | Age; diagnosis of chronic urticaria |

| (Seekis et al., 2017b) [1] | MANOVA; one-way ANOVA; | Age (17–25); language |

| (Sengupta et al., 2025) [25] | SPSS version 27; ANCOVAs | Age; Depression; Anxiety; Stress; Dermatology-specific quality of life; Self-esteem; Well-being |

| (Sherman et al., 2019) [26] | SPSS version 25.0; Chi-square; t-test; R statistics software version 4.5.2; ANCOVAs | Age, gender, education level, skin condition type, time since skin condition onset; whether treatment was received for the skin condition |

| (Singh et al., 2017) [18] | SPSS version 18; Wilcoxon signed-rank test | Age (>15); moderate and severe chronic plaque psoriasis |

| (Yosipovitch et al., 2024) [8] | Focused literature review of mind–body therapies | Pruritus/itch; pain; stress; sleep disturbances; anxiety; depressive symptoms; dermatology-specific quality of life; scratching behavior |

| (Zucchelli et al., 2021) [37] | NVivo© version 15.3.0 software; | Age; gender; participants with a range of appearance-affecting conditions; language |

| Reference | Instruments |

|---|---|

| (Borimnejad et al., 2015) [27] | General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28); |

| (Bundy et al., 2013) [28] | Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) Self-Administered Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (SAPASI) Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) Illness Perception Questionnaire |

| (D’Alton et al., 2019b) [17] | The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ); The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ); The Fears of Compassion Scales (FCS); The World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOLBREF); The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI); The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI); |

| (Kelly et al., 2009) [16] | Depressive Experiences Questionnaire (DEQ); The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); Experiences of Shame Scale (ESS); SKINDEX-16; |

| (Kishimoto et al., 2023) [20] | Dermatology Life Quality Index—Japanese version (DLQI-J) Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) Japanese version Evaluation of itching Self-Compassion Scale—Japanese version SCS-J Japanese version of the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)—Japanese version Japanese version of the Internalized Shame Scale (Japanese version of the ISS) Dermatological treatment adherence Home practice record |

| (Łakuta, 2022) [24] | Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9]; Mental Health Continuum—Short Form [MHCSF]; Self-Affirming Implementation Intention (S-AII); Body-Related Self-Affirming Implementation Intention (BS-AII); |

| (Larsen et al., 2014b) [19] | Self-Administered Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (SAPASI); Self-management measured (heiQ); The Psoriasis Knowledge Questionnaire (PKQ); The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ); |

| (Latifi et al., 2020) [34] | Self-compassion scale (SCS) Body Image Concern Inventory (BICI) |

| (Li et al., 2020) [35] | Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) The Generic Quality of Life Inventory (GQOLI) |

| (Melissant et al., 2021b) [12] | Body Image Scale (BIS); Body Appreciation Scale (BAS-2); Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form (SCS-SF); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), (HADS-A), (HADS-D); Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI-6); International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5); |

| (Mifsud et al., 2021b) [22] | Body Image Scale (BIS: [43]); The Body Appreciation Scale; Self-compassionate attitude (SCA); Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form (SCS-SF); Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS); Short form of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS21); |

| (Muftin et al., 2022) [23] | Other as Shamer Scale (OAS); The Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking & Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS); The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI); |

| (Offenbächer et al., 2021) [31] | Score of Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD); Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM); Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ); Freiburger Mindfulness Inventory (FMI); Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS); Global Transition Items; |

| (Pascual-Sánchez et al., 2020) [29] | Dermatology Life Quality Index—DLQI Beck Depression Inventory—BDI State-trait Anxiety Inventory—STAI Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale—RSES Toronto Alexithymia Scale—TAS-20 |

| (Ridge et al., 2021) [33] | Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS 21); the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ); Urticaria Control Test; PERMA profiler; |

| (Seekis et al., 2017b) [1] | State Body Appreciation Scale-2 (SBAS-2); Body Image States Scale (BISS); |

| (Sengupta et al., 2025) [25] | Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5) Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) |

| (Sherman et al., 2019) [26] | Self-Compassion Scale—Short Form (SCS-SF); Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS); Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire; |

| (Singh et al., 2017) [18] | Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI); Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI); WHO-5 well-being index (WHO-5); Patient health questionnaire (PHQ); Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)-7; |

| (Zucchelli et al., 2021) [37] | Not discriminated |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| CBT | Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy |

References

- Seekis, V.; Bradley, G.L.; Duffy, A. The effectiveness of self-compassion and self-esteem writing tasks in reducing body image concerns. Body Image 2017, 23, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ücker Calvetti, P.; Rivas, R.; Coser, J.; Barbosa, A.; Ramos, D. Biopsychosocial aspects and quality of life of people with chronic dermatoses. Psicol. Saúde Doença 2017, 18, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E.N.; Thompson, A.R.; Norman, P. Depression in people with skin conditions: The effects of disgust and self-compassion. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumsey, N.; Harcourt, D. Body image and disfigurement: Issues and interventions. Body Image 2004, 1, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.; Kent, G. Adjusting to disfigurement: Processes involved in dealing with being visibly different. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 21, 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misery, L.; Schut, C.; Balieva, F.; Bobko, S.; Reich, A.; Sampogna, F.; Altunay, I.; Dalgard, F.; Gieler, U.; Kupfer, J.; et al. White paper on psychodermatology in Europe: A position paper from the EADV Psychodermatology Task Force and the European Society for Dermatology and Psychiatry (ESDaP). J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 2419–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lyga, J. Brain-skin connection: Stress, inflammation and skin aging. Inflamm. Allergy-Drug Targets 2014, 13, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosipovitch, G.; Bernhard, J.D. Chronic pruritus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1625–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Steed, L.; Burden-Teh, E.; Shah, R.; Sanyal, S.; Tour, S.; Dowey, S.; Whitton, M.; Batchelor, J.M.; Bewley, A.P. Identifying key components for a psychological intervention for people with vitiligo—A quantitative and qualitative study in the United Kingdom using web-based questionnaires of people with vitiligo and healthcare professionals. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 2275–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galhardo, A.; Mendes, R.; Massano-Cardoso, I.; Cunha, M. Processos relacionados com a regulação emocional e vergonha e sua associação com os sintomas de depressão, ansiedade e stresse em pessoas com psoríase. Psychologica 2022, 65, e065004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.P.; Lutz, J.; Schuman-Olivier, Z.; Germer, C.; Pollak, S.; Edwards, R.R.; Gardiner, P.; Desbordes, G.; Napadow, V. Brief Self-Compassion Training Alters Neural Responses to Evoked Pain for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Pilot Study. Pain Med. 2020, 21, 2172–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melissant, H.C.; Jansen, F.; Eerenstein, S.E.J.; Cuijpers, P.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; Sherman, K.A.; Laan, E.T.M.; Leemans, C.R.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M. A structured expressive writing activity targeting body image-related distress among head and neck cancer survivors: Who do we reach and what are the effects? Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5763–5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, K.A.; Przezdziecki, A.; Alcorso, J.; Kilby, C.J.; Elder, E.; Boyages, J.; Koelmeyer, L.; Mackie, H. Reducing Body Image–Related Distress in Women with Breast Cancer Using a Structured Online Writing Exercise: Results from the My Changed Body Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1930–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI Critical Appraisal Tools: Checklists for Assessing the Trustworthiness, Relevance and Results of Published Papers. 2024. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Adkins, K.V.; Overton, P.G.; Thompson, A.R. A brief online writing intervention improves positive body image in adults living with dermatological conditions. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1064012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A.C.; Zuroff, D.C.; Shapira, L.B. Soothing Oneself and Resisting Self-Attacks: The Treatment of Two Intrapersonal Deficits in Depression Vulnerability. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2009, 33, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alton, P.; Kinsella, L.; Walsh, O.; Sweeney, C.; Timoney, I.; Lynch, M.; O’Connor, M.; Kirby, B. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Psoriasis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.M.; Narang, T.; Vinay, K.; Sharma, A.; Satapathy, A.; Handa, S.; Dogra, S. Clinic-based group multi-professional education causes significant decline in psoriasis severity: A randomized open label pilot study. Ind. Dermatol. Online J. 2017, 8, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.H.; Krogstad, A.L.; Aas, E.; Moum, T.; Wahl, A.K. A telephone-based motivational interviewing intervention has positive effects on psoriasis severity and self-management: A randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2014, 171, 1458–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishimoto, S.; Watanabe, N.; Yamamoto, Y.; Imai, T.; Aida, R.; Germer, C.; Tamagawa-Mineoka, R.; Shimizu, R.; Hickman, S.; Nakayama, Y.; et al. Efficacy of integrated online mindfulness and self-compassion training for adults with atopic dermatitis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2023, 159, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M.P.; Thompson, A.R.; Emerson, L.-M. Compassion-focused self-help for psychological distress associated with skin conditions: A randomized feasibility trial. Psychol. Health 2020, 35, 1095–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifsud, A.; Pehlivan, M.J.; Fam, P.; O’Grady, M.; van Steensel, A.; Elder, E.; Gilchrist, J.; Sherman, K.A. Feasibility and pilot study of a brief self-compassion intervention addressing body image distress in breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2021, 9, 498–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muftin, Z.; Gilbert, P.; Thompson, A.R. A randomized controlled feasibility trial of online compassion—focused self-help for psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 186, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łakuta, P. A Factorial Randomized Controlled Trial of Implementation-Intention-Based Self-Affirmation Interventions: Findings on Depression, Anxiety, and Well-being in Adults with Psoriasis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 795055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Wagani, R. Mindful self-compassion for psychological distress associated with skin conditions: An online intervention study. Ind. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2024, 91, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, K.A.; Roper, T.; Kilby, C.J. Enhancing self-compassion in individuals with visible skin conditions: Randomised pilot of the ‘My Changed Body’ self-compassion writing intervention. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2019, 7, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borimnejad, L.; Firooz, A.; Mortazavi, H.; Aghazadeh, N.; Halaji, Z. The Effect of Expressive Writing on Psychological Distress in Patients with Vitiligo: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Client-Centered Nurs. Care 2015, 1, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bundy, C.; Pinder, B.; Bucci, S.; Reeves, D.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Tarrier, N. A novel, web-based, psychological intervention for people with psoriasis: The electronic Targeted Intervention for Psoriasis (eTIPs) study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 169, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual-Sánchez, A.; Fernández-Martín, P.; Saceda-Corralo, D.; Vañó-Galván, S. Impact of psychological intervention in women with alopecia areata universalis: A pilot study. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 2020, 111, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman-Lagerlöf, E.; Bergman, A.; Lindefors, N.; Bradley, M. Exposure-based cognitive behavior therapy for atopic dermatitis: An open trial. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2019, 48, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offenbächer, M.; Seitlinger, M.; Münch, D.; Schnopp, C.; Darsow, U.; Harfensteller, J.; Schmid-Grendelmeier, P.; Ring, J.; Kohls, N. A Pilot Study of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Programme in Patients Suffering from Atopic Dermatitis. Psych 2021, 3, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfensteller, J. An Open Trial on the Feasibility and Efficacy of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention with Psychoeducational Elements on Atopic Eczema and Chronic Itch. Psych 2022, 4, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridge, K.; Conlon, N.; Hennessy, M.; Dunne, P.J. Feasibility assessment of an 8-week attention-based training programme in the management of chronic spontaneous urticaria. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, Z.; Soltani, M.; Mousavi, S. Evaluation of the effectiveness of self-healing training on self-compassion, body image concern, and recovery process in patients with skin cancer. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 40, 101180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L. Efficacy of psychological intervention for patients with psoriasis vulgaris: A prospective study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 0300060520961674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.; Castoldi, L.; Kijner, L. A pele expressando o afeto: Uma intervenção grupal com pacientes portadores de psicodermatoses. Contextos Clínicos 2011, 4, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchelli, F.A.; Donnelly, O.; Sharratt, N.D.; Hooper, N.; Williamson, H.M. Patients’ Experiences of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy-Based Approach for Psychosocial Difficulties Relating to an Appearance-Affecting Condition. Eur. J. Couns. Psychol. 2021, 9, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, E.; Chung, M.; Yeroushalmi, S.; Hakimi, M.; Bhutani, T.; Liao, W. Mindfulness and meditation for psoriasis: A systematic review. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 2273–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafidi, B.; Kondapi, K.; Beestrum, M.; Basra, S.; Lio, P. Psychological therapies and mind–body techniques in the management of dermatologic diseases: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 755–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Jensen, C.G.; Khoury, L.; Deleuran, B.; Blom, E.S.; Breinholt, T.; Christensen, R.; Skov, L. Effectiveness of mind–body intervention for inflammatory conditions: Results from a 26-week randomized, non-blinded, parallel-group trial. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, R.M.; Ploszajski, M.; Purcell, C.; Pattinson, R.; Jones, B.; Wren, G.H.; Hughes, O.; Ridd, M.J.; Thompson, A.R.; Bundy, C. A mixed methods systematic review of digital interventions to support the psychological health and well-being of people living with dermatological conditions. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1024879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, O.; Shelton, K.H.; Penny, H.; Thompson, A.R. Parent and child experience of skin conditions: Relevance for the provision of mindfulness-based interventions. Br. J. Dermatol. 2023, 188, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, P.; Fletcher, I.; Lee, A.; Al Ghazal, S. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2001, 37, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, R.G.; Gupta, M.A.; Gupta, A.K. Depression and skin disease. Dermatol. Clin. 2005, 23, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, V.; Leite, Â.; Constante, D.; Correia, R.; Almeida, I.F.; Teixeira, M.; Vidal, D.G.; e Sousa, H.F.P.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Teixeira, A. The Mediator Role of Body Image-Related Cognitive Fusion in the Relationship between Disease Severity Perception, Acceptance and Psoriasis Disability. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemer, K.S.; Lamphere, B.R.; Raque-Bogdan, T.L.; Schmidt, C.K. A randomized controlled study of writing interventions on college women’s positive body image. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türk, K.E.; Yılmaz, M. The effect on quality of life and body image of mastectomy among breast cancer survivors. Eur. J. Breast Health 2018, 14, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birdi, G.; Cooke, R.; Knibb, R.C. Impact of atopic dermatitis on quality of life in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 59, e75–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.S.; Slavich, G.M. Mindfulness meditation and the immune system: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1373, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, T.J.; Dimolareva, M. The effect of mindfulness-based interventions on immunity-related biomarkers: A comprehensive meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 92, 102124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Research Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (“Skin Diseases” [Mesh] OR dermatos * OR “atopic dermatitis” OR eczema OR psoriasis OR vitiligo) AND (“Psychotherapy” [Mesh] OR “Psychosocial Intervention” OR psychotherapy * OR “cognitive behavioral therapy” OR mindfulness OR “acceptance and commitment therapy” OR self-compassion OR “body image” OR “support group *”) |

| Google Scholar | (“atopic dermatitis” OR eczema) (psychotherapy OR mindfulness OR “cognitive behavioral therapy”) (psoriasis OR vitiligo) (“psychological intervention” OR “support group” OR “body image”) (“skin disease” OR dermatosis) (psychotherapy OR “acceptance and commitment therapy” OR self-compassion) |

| PsycNet | (DE “Dermatological Disorders” OR TI (dermatos * OR “skin disease *” OR “atopic dermatitis” OR eczema OR psoriasis OR vitiligo) OR AB (dermatos * OR “skin disease *” OR “atopic dermatitis” OR eczema OR psoriasis OR vitiligo)) AND (MH “Psychotherapy+” OR MH “Cognitive Behavior Therapy” OR MH “Mindfulness” OR MH “Body Image” OR DE “Psychosocial Interventions” OR DE “Support Groups” OR TI (psychotherapy * OR “psychological intervention” OR “cognitive behavioral therapy” OR mindfulness OR “body image”) OR AB (psychotherapy * OR “psychological intervention” OR “cognitive behavioral therapy” OR mindfulness OR “body image”)) |

| Study Title | Reference and Metrics 1 | Main Aim | Methodology | Psychological Intervention | Main Results | Discussion/Conclusions | Key Outcomes & Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-help targeting body image among adults living with dermatological conditions: An evaluation of a brief writing intervention | (Adkins, 2021) [15] Q1 (high) | Dermatological conditions can affect how individuals feel about their bodies. This research therefore seeks to evaluate the potential for a brief writing intervention, focused on body functionality, to improve body image in adults living with a range of dermatological conditions. | Randomized Controlled Trial | One week writing intervention, focused on body functionality, to improve body image | For participants with relatively low or mid-range scores on baseline body appreciation and functionality appreciation, there were medium-to-large effects of the intervention. Effects were smaller, with all but-one remaining significant at one-month follow-up and in intention-to-treat analyses. No effects of the intervention were found for measures of appearance anxiety, skin-related shame, and skin-related quality-of-life. | One-week writing intervention has the potential to improve positive aspects of body image, but not appearance and skin-related distress in adults living with a dermatological condition. However, these findings should be considered in the context of high attrition across both the intervention and control conditions. | Medium-to-large improvements in body and functionality appreciation (p < 0.001); no effects on appearance anxiety, skin shame, or dermatology-related quality of life. |

| Mindfulness and Meditation for Psoriasis: A Systematic Review | (Bartholomew et al., 2022) [38] Q1 (high) | The aim of this review is to provide an update on research studies investigating the role of mindfulness and meditation in treating psoriasis symptoms, severity, and quality of life. | Systematic review | Guided meditation and mindfulness-based interventions were used to reduce psoriasis severity and improve quality of life | Among six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included, five showed improvement in psoriasis severity measured by the self-administered Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (saPASI) after 8 to 12 weeks of guided meditation. Additionally, one RCT and one non-randomized controlled trial reported mental health benefits, including reduced anxiety and depression, following mindfulness and meditation interventions | The findings suggest that mindfulness and meditation are promising non-pharmacological interventions for improving both psoriasis severity and patients’ quality of life in the short term | Five of six RCTs reported significant between-group improvements in psoriasis severity (saPASI) following 8–12 weeks of mindfulness or meditation; psychological outcomes (stress, quality of life, anxiety, depression, mindfulness) showed limited or inconsistent between-group effects; long-term effects remain unclear. |

| The Effect of Expressive Writing on Psychological Distress in Patients with Vitiligo: A Randomized Clinical Trial | (Borimnejad et al., 2015) [27] Q2 (medium) | Assess whether expressive writing, as a psychological intervention, reduces psychological distress in vitiligo patients undergoing phototherapy. | Randomized study. | Expressive writing | There was a statistically significant reduction in GHQ-28 scores in both groups 4 weeks after the intervention, but not in psychiatric distress. | The effect of expressive writing remains equivocal when it comes to reducing psychological distress in vitiligo patients. The use of phototherapy may be associated with a decline in psychological distress. | No significant between-group differences in GHQ-28 total or sub-scores after 4 weeks (p = 0.7); significant within-group reductions observed in both groups (Group A: 47.9 ± 11.71, p = 0.000; Group B: 48.94 ± 10.69, p = 0.000). |

| A novel, web-based, psychological intervention for people with psoriasis: the electronic Targeted Intervention for Psoriasis (eTIPs) study | (Bundy et al., 2013) [28] Q1 (high) | To determine whether an electronic CBT intervention for psoriasis (eTIPs) would reduce distress, improve quality of life and clinical severity in patients with psoriasis. | Randomized study | Electronic, web-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy intervention | Anxiety scores between groups were significantly reduced only for complete cases, depression scores did not change, as did psoriasis severity scores. Quality of life scores improved in both analyses. | This first online CBT intervention for people with skin conditions has shown improved anxiety and quality of life in patients with psoriasis. | Significant between-group reduction in anxiety scores (p = 0.004); no significant between-group differences in depression or psoriasis severity; significant between-group improvement in quality of life (p = 0.042). |

| Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Psoriasis: a Randomized Controlled Trial | (D’Alton et al., 2019b) [17] Q1 (high) | This study aims to compare the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy (MBSCT) and self-help MBSCT (MBSCT-SH) compared to treatment as usual (TAU) in improving the long-term psychological and physical outcomes of individuals with psoriasis. | Randomized controlled trial. | Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), Mindfulness-based self-compassion therapy (MBSCT) and Self-help MBSCT (MBSCT-SH) | Although participants reported that MBIs were beneficial, no statistically significant differences were found in psychological well-being, severity of psoriasis symptoms or quality of life compared to TAU alone at post-treatment (follow-up 6 or 12 months). | There were no statistically significant differences between the MBIs in improving anxious or depressive symptoms, nor in increasing self-compassion. | No significant between-group differences in psychological well-being, psoriasis symptom burden, or quality of life were observed at post-treatment, 6-month, or 12-month follow-up; |

| The skin expressing affection: a group intervention with patients suffering from psychodermatoses | (Da Silva et al., 2011) [36] Q1 (high) | To analyze a group intervention as a tool to promote new channels for the expression of affections in patients with psychodermatoses being treated at a public dermatology outpatient clinic. | Exploratory and descriptive study of a qualitative nature | Intervention group | The results show that the group was able to become a space for listening to and accepting suffering, allowing participants to see themselves and others, as well as to rehearse movements and changes in the way they relate to themselves and others. | The conclusion is that group intervention can be an important tool in dealing with patients with psychodermatoses, since it highlights the emotional aspects of this disease, favoring a new perspective and a more integrated model of care. | Group intervention facilitated emotional processing, self-acceptance, and improved interpersonal awareness; qualitative improvements reported, but no quantitative between-group comparisons were provided |

| An Open Trial on the Feasibility and Efficacy of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention with Psychoeducational Elements on Atopic Eczema and Chronic Itch | (Harfensteller, 2022) [32] Q1 (high) | This article reports on a novel Mindfulness based Training for chronic Skin Conditions (MBTSC) with psychoeducational elements that was developed with the goal of improving self-regulation including stress management and emotion regulation in patients and to help in coping with disease symptoms such as itch and scratching. | Open trial | Mindfulness based Training for chronic Skin Conditions (MBTSC) | Quantitative data showed improvements in disease severity, itch perception and stress levels with small to medium effect sizes. Psychological distress increased at post-treatment—significantly in the case of depression. Qualitative data highlighted the mixed effects of MBTSC on symptoms. Treatment acceptability was high and 100% of the participants completed the intervention | These data indicate that MBTSC is feasible and that it might be a useful tool as adjunct therapy for AD. Further studies with larger samples and control groups are needed. | Moderate reductions in disease severity (PO-SCORAD: d = 0.65, p = 0.290) and itch perception (EIQ: d = 0.41, p = 0.407), with greater decrease in the affective-emotional dimension of itch (d = 0.51, p = 0.320, not significant); moderate improvements in subjective stress and mindfulness, not statistically significant; significant increase in depression (HADS-D: d = 1.43, p = 0.033) and no significant change in anxiety (HADS-A: d = 0.28, p = 0.530); high acceptability with 100% completion; subjective improvements reported in symptoms and disease coping; no between-group comparisons were performed. |

| Exposure-based cognitive behavior therapy for atopic dermatitis: an open trial | (Hedman-Lagerlöf et al., 2019) [30] Q1 (high) | The aim of the present study was to test the treatment’s acceptability and preliminary efficacy in adults with AD. | Pilot study | Exposure-based Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy for adult with Atopic Dermatitis | The results showed significant and large baseline to posttreatment improvements on self-reported measures of AD symptoms (p = 0.020) and general anxiety (p = 0.005), but there was no significant improvement in depression or quality of life. Treatment satisfaction was high, and most participants (67%) completed the treatment. | We conclude that exposure-based CBT for adult AD can be feasible, acceptable, and potentially efficacious. | Significant baseline-to-posttreatment improvements in AD symptoms (p = 0.020) and general anxiety (p = 0.005); no significant change in depression or quality of life; no between-group comparisons were performed. |

| Compassion-focused self-help for psychological distress associated with skin conditions: a randomized feasibility trial | (Hudson et al., 2020) [21] Q1 (high) | Test the feasibility of a self-help intervention based on Compassion-Focused Theory (CBT) and understand the effects of the treatment on a population of adults with skin diseases. | Randomized controlled study | Compassion-Focused Theory (CFT) self-help intervention | The CFT self-help intervention shows promise results in treating psychological distress associated with skin conditions. | Although the study indicates that the intervention may be promising in treating psychological distress associated with skin problems, further testing of the intervention is not feasible without significant methodological changes, including the way the treatment is administered. | Significant between-group improvements in stress, anxiety, depression, self-compassion, and dermatology-specific quality of life among completers (moderate effect sizes); effects remained significant in intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses but with reduced effect sizes (small); 51% completion rate; participants practiced a median of 9/14 days. |

| Soothing Oneself and Resisting Self-Attacks: The Treatment of Two Intrapersonal Deficits in Depression Vulnerability | (Kelly et al., 2009) [16] Q1 (high) | Test the impact of two self-help interventions designed to reduce depression in acne patients, by improving difficulties with self-soothing and resisting self-attacks. | Randomized controlled trial. | Self-help interventions: self-soothing and resist self-attacks | The results indicate that among acne sufferers, practicing a more calming style of self-talk can reduce shame and skin problems, just as practicing stronger posture and more resilient self-talk can reduce depression, shame and skin complaints. | In two weeks, the self-soothing intervention lowered shame and skin complaints. The attack-resisting intervention lowered depression, shame, and skin complaints, and was especially effective at lowering depression for self-critics. | Significant between-group improvements were observed in depression (attack-resisting vs. control, F (1,69) = 6.00, p = 0.02), shame (self-soothing: F (1,71) = 5.13, p = 0.03; attack-resisting: F (1,71) = 6.92, p = 0.01), and acne-related emotional distress (self-soothing: F (1,70) = 10.40, p < 0.01; attack-resisting: F (1,70) = 17.47, p < 0.001) compared to controls. Physical acne symptoms decreased significantly in the self-soothing condition (F (2,70)= 6.25, p = 0.01) with a trend for the attack-resisting condition (F (2,70) = 3.38, p = 0.07); no differences were found between interventions. |

| Efficacy of Integrated Online Mindfulness and Self-compassion Training for Adults with Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial | (Kishimoto et al., 2023) [20] Q1 (high) | To evaluate the efficacy of mindfulness and self-compassion training in improving the QOL for adults with AD. | Randomized clinical trial | Integrated Online Mindfulness and Self-compassion Training | Primary outcome: change in dermatology life quality score from baseline to week 13. Secondary outcomes: eczema severity, itch- and scratching-related visual analog scales, self-compassion and all of its subscales, mindfulness, psychological symptoms, and participants’ adherence to dermatologist-advised treatments. | These findings suggest that mindfulness and self-compassion training is an effective treatment option for adults with AD. | Significant between-group improvement in DLQI at 13 weeks (mean difference = −6.34, 95% CI −8.27 to −4.41, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d =–1.06); all secondary outcomes also showed greater improvements in the intervention group compared to the waiting list, although exact between-group statistics for these were not reported. |

| A Factorial Randomized Controlled Trial of Implementation- Intention- Based Self-Affirmation Intervention: Findings on Depression, Anxiety and Well-being in Adults With Psoriasis | (Łakuta, 2022) [24] Q1 (high) | Study whether strengthening the specificity element within the body-related self-affirmative implementation intention intervention compared to general self-affirmative implementation intention would provide greater improvements for adults with psoriasis. | Randomized Study | Implementation- Intention- Based Self-affirmation interventions | Exploratory analysis revealed two moderating effects of age and self-esteem, pointing to borderline conditions of the interventions. | These findings offer deeper insights into the negative effects also reported in previous work and highlight that self-affirmation interventions must be further investigated and optimized before they can be widely implemented in real-life contexts. | Significant within-group improvements over time were observed for depressive symptoms (F (2, 377) = 11.91, p < 0.001), anxiety (F (2, 380) = 30.82, p < 0.001), and well-being (F (2, 372) = 11.94, p < 0.001), but no significant between-group differences or time × group interactions were detected for depressive symptoms (F (4, 377) = 0.12, p = 0.978), anxiety (F (4, 380) = 1.41, p = 0.230), or well-being (F (4, 372) = 0.19, p = 0.942). |

| A telephone-based motivational interviewing intervention has positive effects on psoriasis severity and self-management: a randomized controlled trial | (Larsen et al., 2014b) [19] Q1 (high) | Evaluate the effects of a 3-month individual motivational interviewing intervention on psoriasis patients (with a total follow-up of 6 months) after climatherapy/heliotherapy (CHT). | Randomized controlled trial. | 3-month individual motivational interviewing intervention | There were significant overall treatment effects in the study group in terms of the SAPASI score. The parameters of lifestyle change and knowledge about the disease were significantly better in the experimental group. | The results showed that the study group differed from the control group at 6 months after CHT in terms of disease severity, knowledge about psoriasis, self-efficacy and some lifestyles change parameters. | Significant between-group improvements were observed in the study group for SAPASI scores, three self-management domains of heiQ, and self-efficacy (p < 0.05). Lifestyle change parameters were also significantly better in the study group. Additionally, illness perception differed between groups at 3 months (p = 0.014), and psoriasis knowledge was significantly higher in the study group at 6 months (p = 0.017). |

| Evaluation of the effectiveness of self-healing training on self-compassion, body image concern, and recovery process in patients with skin cancer | (Latifi et al., 2020) [34] Q1 (high) | To investigate the effect of self-healing training on self-compassion, body image concern, and recovery process in patients with skin cancer. | Quasi-experimental; pre- and post-test with a control group | Self-healing training on self-compassion, body image concern, and recovery process | Self-healing training significantly increased self-compassion, including self-kindness, self-judgment, and sense of common humanity, and decreased the level of body image concern, isolation, and over-identification. | The self-healing is an appropriate intervention method to increase self-compassion and reduce body image concern and thus accelerate the process of skin cancer recovery. | Following self-healing training, significant increases were observed in self-compassion (self-kindness, self-judgment, and sense of common humanity; p < 0.01) and significant decreases in body image concern, isolation, and over-identification (p < 0.05) |

| Efficacy of psychological intervention for patients with psoriasis vulgaris: a prospective study | (Li et al., 2020) [35] Q3 (low) | To examine the effect of a psychological intervention on patients with psoriasis vulgaris. | Prospective study | Several | The study group showed significantly better SCL-90 and GQOLI scores than the non-psoriasis group. After treatment, they also had lower SDS and SAS scores, and higher satisfaction and compliance rates compared to the control group. | Psychological intervention may be beneficial for improving quality of life and the therapeutic efficacy of drugs in patients with psoriasis. | Significant between-group improvements were observed after treatment, with the study group showing better SCL-90 and GQOLI scores compared with the control group. Additionally, the study group had improved SDS (31.99 ± 4.54 vs. 44.08 ± 4.52) and SAS scores (28.36 ± 4.52 vs. 40.14 ± 6.33), as well as higher patient satisfaction and compliance rates. |

| Feasibility and pilot study of a brief self-compassion intervention addressing body image distress in breast cancer survivors | (Mifsud et al., 2021b) [22] Q1 (high) | Explore the feasibility and acceptability of the MyCB intervention, with and without an additional meditation component, in breast cancer survivors. | Randomized controlled study | Brief web-based self-compassion intervention MyCB, alone and with meditation | Adherence to MyCB writing and meditation was moderate, and acceptability was high for both MyCB and MyCB + M. Post-intervention state self-compassion and positive affect increased. | The results provide preliminary evidence for the efficacy and potential clinical use of the brief web-based self-compassion intervention MyCB, alone and with the addition of meditation, to increase self-compassion and psychological well-being in breast cancer survivors. | Post-intervention, MyCB (combined) showed increased self-compassionate attitude (F1,23 = 12.10, p = 0.002, d = 0.95) and positive affect (F1,23 = 4.34, p = 0.046, d = 0.83) compared to EW. At 1-month follow-up, body image distress decreased (F1,23 = 8.19, p = 0.009), trait self-compassion increased for MyCB + M vs. MyCB (t23 = 2.70, p = 0.013, d = 0.74), and anxiety decreased for MyCB + M vs. EW (t23 = −3.464, p = 0.002, d = 0.31) and MyCB (t23 = −3.893, p = 0.001, d = 0.22). No other between-group differences were significant at baseline or follow-up. |

| A randomized controlled feasibility trial of online compassion-focused self-help for psoriasis* | (Muftin et al., 2022) [23] Q2 (medium) | Test the feasibility and acceptability of two studies that theoretically developed self-help interventions designed to reduce feelings of shame and improve quality of life. | Randomized controlled study | Online compassion and mindfulness-focused self-help | Both interventions showed moderate but statistically significant reductions in shame and improvements in quality of life. | Self-help based on compassion and mindfulness is acceptable and can reduce feelings of shame and improve the quality of life for people living with psoriasis. | Both interventions were well accepted, with over 70% of completers reporting the materials were helpful and produced modest but significant reductions in shame (Cohen’s d = 0.20) and improvements in quality of life (Cohen’s d = 0.40); overall attrition was 29%. |

| A Pilot Study of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Programme in Patients Suffering from Atopic Dermatitis | (Offenbächer et al., 2021) [31] Q1 (high) | Assess the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Program in patients with atopic dermatitis. | Pilot study | Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Programme | The IMF indicated significant improvement in the “presence” and “acceptance” subscales. There was also a tendency to less stress. | Considering the long history and the severity of the disease burden, the effects of this intervention appear promising as a complement to conventional treatments. | Pre-post analysis showed significant improvements in the FMI presence and ‘acceptance’ subscales. A tendency toward reduced stress was also observed. These findings were supported by participants’ qualitative statements. |

| Impact of Psychological Intervention in Women with Alopecia Areata Universalis: a Pilot Study | (Pascual-Sánchez et al., 2020) [29] Q3 (low) | To evaluate the usefulness of cognitive–behavioral therapy as a psychological intervention within a psychoeducational group setting for women with alopecia areata universalis (AAU)n, and to identify the key elements that can help improve the quality of care in this area. | Randomized pilot study. | Cognitive–behavioral therapy as a psychological intervention within a psychoeducational group | The intervention improved sleep and quality of life, though emotional difficulties like alexithymia increased. Anxiety and depression remained linked to well-being throughout. | The results suggest that psychological intervention can improve quality of life and sleep in women with AAU, key aspects of their well-being. While anxiety showed only slight improvement—possibly due to the short treatment duration—more complex issues like anxiety and depression may need longer interventions. The rise in alexithymia might indicate the early stages of emotional awareness. Future studies are needed to explore these findings further. | The psychological intervention in women with AAU resulted in significant improvements in quality of life (DLQI, pre-post comparison, p = 0.041) and sleep quality (OSQ, p < 0.01), alongside a paradoxical increase in alexithymia (TAS-20, p = 0.025). No significant changes were observed in depression, anxiety, or self-esteem. |

| Psychological Therapies and Mind–Body Techniques in the Management of Dermatologic Diseases | (Rafidi et al., 2022) [39] Q1 (high) | To determine the efficacy of various psychological therapies and mind–body techniques in the management of common dermatologic diseases in individuals of all ages. | Systematic Review | Various psychological therapies and mind–body techniques including cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based interventions, and habit reversal therapy. | The studies focused mainly on psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, along with other skin conditions such as vitiligo, pruritus, and acne. The identified therapies showed positive effects on both physical symptoms and psychological well-being | There is a bidirectional relationship between skin diseases and psychological distress. Psychological therapies and mind–body techniques are effective adjunctive treatments in managing dermatologic diseases. The review highlights the potential benefits of integrating these interventions into standard care, especially for select patients | Based on the analysis of included studies and assessment of evidence quality, the most promising interventions were cognitive–behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based interventions, and habit reversal therapy. |

| Feasibility assessment of an 8-week attention-based training programme in the management of chronic spontaneous urticaria | (Ridge et al., 2021) [33] Q1 (high) | Developing a mindfulness-based training course for individuals with chronic spontaneous urticaria. | Prospective cutting study | Mindfulness-based training course (ABT programme) | A decrease in the severity of urticaria symptomatology as measured by the urticaria control test was observed after completion of the intervention. | Integration of an ABT program into routine clinical care for patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria is feasible and was considered acceptable and valuable by the individuals who participated. | Within-group improvements were observed in urticaria symptom severity, psychological well-being, and mindfulness practice adherence following the 8-week ABT programme; however, no between-group comparisons were reported, and participant retention was limited (33% dropout). |

| The effectiveness of self-compassion and self-esteem writing tasks in reducing body image concerns | (Seekis et al., 2017b) [1] Q1 (high) | Investigate whether single-session self-compassion and self-esteem writing tasks enrich the body image concerns evoked by a negative body image induction. | Randomized study. | Single-session self-compassion and self-esteem writing tasks | The self-compassion writing group showed higher post-treatment body appreciation and higher body satisfaction. | Writing-based interventions, especially those that enhance self-compassion, may help improve certain body image concerns. | Significant within-group improvement in body appreciation and body satisfaction was observed in the self-compassion writing group compared to control (post-treatment and 2-week follow-up), while no between-group differences were found for appearance anxiety. |

| Mindful self-compassion for psychological distress associated with skin conditions: An online intervention study | (Sengupta et al., 2025) [25] Q2 (medium) | To evaluate the impact of a Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) intervention on depression, anxiety, stress, self-esteem, well-being, and dermatology-specific quality of life in adults with chronic skin conditions. | Randomized controlled study | Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) a structured mindfulness-based self-compassion training program incorporating elements of personal development and psychotherapy, delivered online | The study reported statistically significant improvements in the intervention group, with reduced levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, as well as increased self-esteem, well-being, and dermatology-specific quality of life when compared to the waitlist control group | MSC was shown to be an effective approach for managing psychological distress associated with chronic skin conditions. | Significant between-group improvements were observed in depression (p < 0.001), anxiety (p < 0.001), stress (p < 0.001), dermatology-related quality of life (p < 0.001), self-esteem (p < 0.001), and well-being (p < 0.001) in the mindful self-compassion intervention group compared to waitlist control. |

| Enhancing self-compassion in individuals with visible skin conditions: randomized pilot of the ‘My Changed Body’ self-compassion writing intervention | (Sherman et al., 2019) [26] Q1 (high) | Investigate the feasibility of applying the My Changed Body intervention to address visible body image issues related to the skin. | Randomized pilot study. | Self-compassion writing intervention “My Changed Body” | Self-compassion and negative affect showed improvements in the experimental group compared to the control group. There was no between groups difference at follow-up in positive affect. | The My Changed Body writing intervention may provide benefit to individuals with visible skin condition. | Significant between-group improvements were observed in self-compassion (p = 0.006) and reductions in negative affect (p = 0.028) in the self-compassion writing intervention group compared to control, while no significant between-group differences were found for positive affect. |

| Clinic-based Group Multi-professional Education Causes Significant Decline in Psoriasis Severity: A Randomized Open Label Pilot Study | (Singh et al., 2017) [18] Q3 (low) | Test the benefits of a multidisciplinary group intervention using psychoeducation. | Randomized controlled trial. | Multidisciplinary group intervention using psychoeducation | After the intervention, there was a statistically significant improvement in the mean scores on the PASI, DLQI and WHO-5 in the experimental group, unlike what was observed in the control group. There was a statistically significant improvement in PHQ 9 scores in both groups. The scores on the PHQ 15 and the GAD 7 showed no statistically significant differences. | Psychoeducational intervention group demonstrated improvements in clinical and psychological outcomes in patients with psoriasis. | Significant improvements in PASI, DLQI, and WHO-5 were observed in the intervention group at 6 months post-intervention (p < 0.01), while PHQ-9 scores improved in both intervention and control groups (p < 0.01). No significant changes were observed for PHQ-15 or GAD-7, and between-group differences were not reported |

| Integrative Treatment Approaches with Mind–Body Therapies in the Management of Atopic Dermatitis | (Yosipovitch et al., 2024) [8] Q1 (high) | To highlight the role of psychodermatology in atopic dermatitis by exploring mind–body therapies that address the psychological factors influencing the severity and management of the disease. | Focused literature review | Cognitive–behavioral therapy, mindfulness, meditation, hypnotherapy, habit reversal, relaxation techniques, EMDR, music therapy, massage, education, and other mind–body therapies. | Mind–body therapies may reduce pruritus, psychological stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, pain, and improve sleep and adherence to treatment in patients with atopic dermatitis. | Mind–body therapies show potential benefits as adjunct treatments for atopic dermatitis, but more rigorously designed trials are needed to confirm long-term efficacy | Integrative mind–body therapies (MBT), when combined with conventional pharmacologic treatment, show potential benefits for patients with atopic dermatitis, including reductions in pruritus, pain, psychological stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and improvements in sleep quality and treatment adherence. |

| Patients’ Experiences of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy-Based Approach for Psychosocial Difficulties Relating to an Appearance-Affecting Condition | (Zucchelli et al., 2021) [37] Q1 (high) | Investigate the lived experiences of patients with various dermatological conditions and appearance-related concerns who took part in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy sessions. | Qualitative study. | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) -Based Approach | ACT-based individual therapy seemed to help speed up the process of accepting a changed appearance, which the participants highlighted as an important factor. | Participants emphasized the importance of therapists expressing compassion and helping patients cultivate self-compassion in their daily lives. | ACT-based individual therapy improved acceptance of appearance and fostered body confidence and self-compassion, as reported by participants. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almeida, V.; Ferreira, Â.; Veloso, A.; Rocha, R.; Leite, Â.; Teixeira, A. Psychological Interventions for the Treatment of Patients with Chronic Dermatoses: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2947. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222947

Almeida V, Ferreira Â, Veloso A, Rocha R, Leite Â, Teixeira A. Psychological Interventions for the Treatment of Patients with Chronic Dermatoses: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2947. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222947

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmeida, Vera, Ângela Ferreira, Ana Veloso, Rita Rocha, Ângela Leite, and Ana Teixeira. 2025. "Psychological Interventions for the Treatment of Patients with Chronic Dermatoses: A Systematic Literature Review" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2947. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222947

APA StyleAlmeida, V., Ferreira, Â., Veloso, A., Rocha, R., Leite, Â., & Teixeira, A. (2025). Psychological Interventions for the Treatment of Patients with Chronic Dermatoses: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare, 13(22), 2947. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222947