Patient-Reported Outcomes on Quality of Life in Older Adults with Oral Pemphigus

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology and Burden of Oral Pemphigus in Older Adults

1.2. Pathophysiology and Age-Associated Vulnerabilities

1.3. Oral Health–Related Quality of Life in Geriatric Populations

1.4. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Autoimmune Oral Diseases

1.5. Research Gap and Rationale for the Present Study

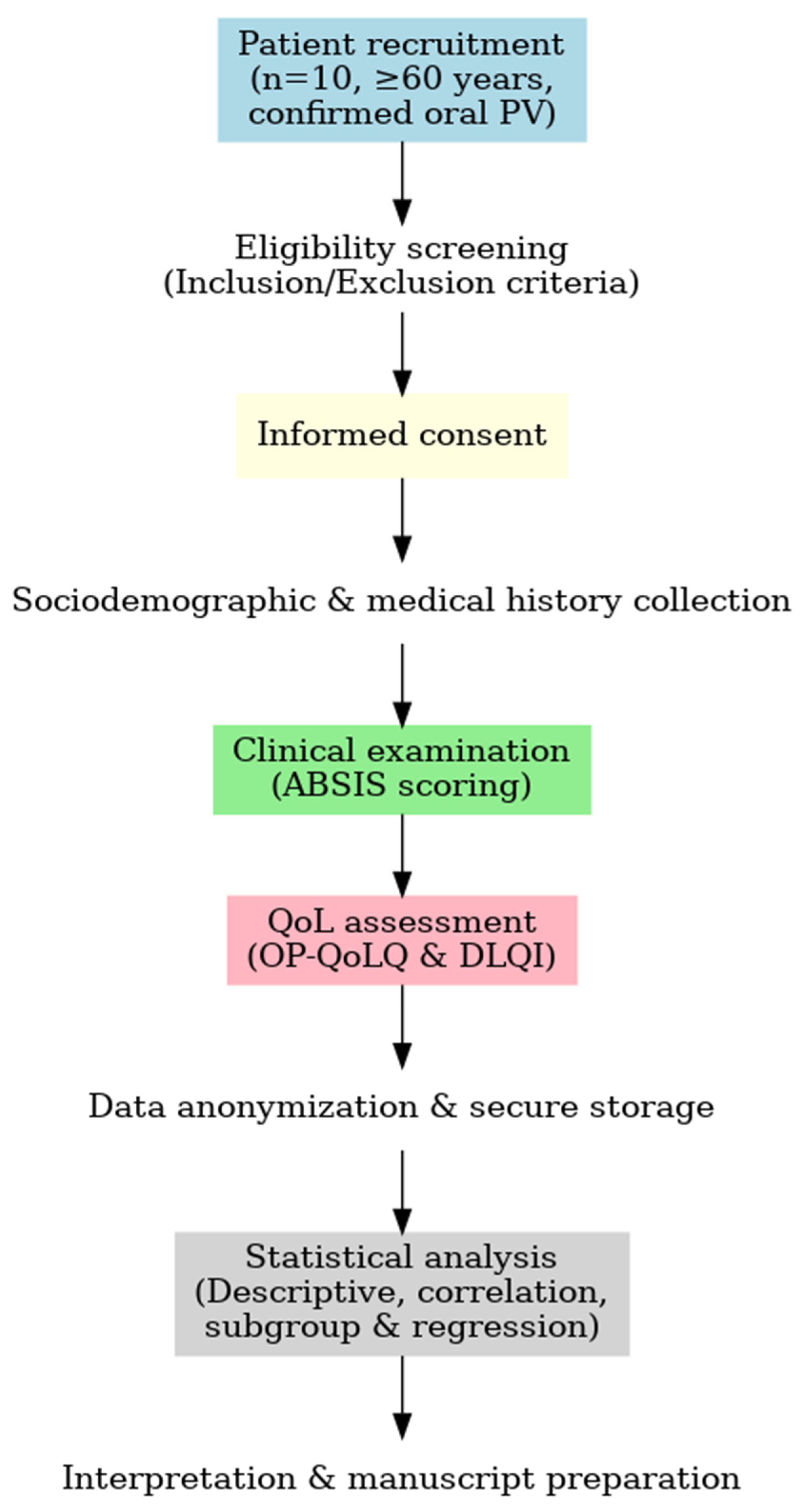

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Age ≥ 60 years at recruitment.

- Confirmed diagnosis of oral PV based on clinical examination showing oral mucosal erosions/blisters, histopathology demonstrating intraepithelial blister formation with acantholysis, and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) revealing intercellular IgG and/or C3 deposition.

- Predominant oral involvement (with or without limited skin lesions) within the last six months.

- Ability to complete questionnaires independently or with minimal assistance.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Other autoimmune mucocutaneous disorders (e.g., mucous membrane pemphigoid, erosive lichen planus).

- Severe cognitive or psychiatric impairment preventing valid questionnaire completion.

- Acute systemic illness or hospitalization within the past four weeks.

- Participation in another interventional clinical trial at the time of recruitment.

2.2.3. Sample Size Justification

2.3. Clinical Evaluation

2.4. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

2.4.1. Oral Pemphigus–Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (OP-QoLQ)

- Physical symptoms—pain, burning, bleeding, difficulty swallowing.

- Functional limitations—chewing, speaking, maintaining oral hygiene.

- Emotional well-being—anxiety, embarrassment, frustration.

- Social participation—avoidance of social gatherings, communication difficulties.

- Treatment burden—side effects, time for care, treatment accessibility.

2.4.2. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)

- Symptoms and feelings

- Daily activities

- Leisure

- Work and school

- Personal relationships

- Treatment

- 0–1: no effect

- 2–5: small effect

- 6–10: moderate effect

- 11–20: very large effect

- 21–30: extremely large effect

2.4.3. Rationale for Instrument Selection

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

- Sociodemographic data—age, sex, education level, living situation.

- Medical history—disease duration, comorbidities, current treatments.

- Clinical assessment—ABSIS scoring by the calibrated examiner.

- Patient-reported outcomes—self-administration of OP-QoLQ and DLQI in a quiet, private setting. Assistance was available for participants with visual or motor limitations, without influencing responses.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

- Subgroup comparisons—Independent-samples t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests were applied to compare QoL scores by sex, comorbidity status, and disease duration (<2 years vs. ≥2 years).

- Multiple group comparisons—One-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to explore differences in QoL across treatment groups (systemic corticosteroids, rituximab, combination therapy).

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

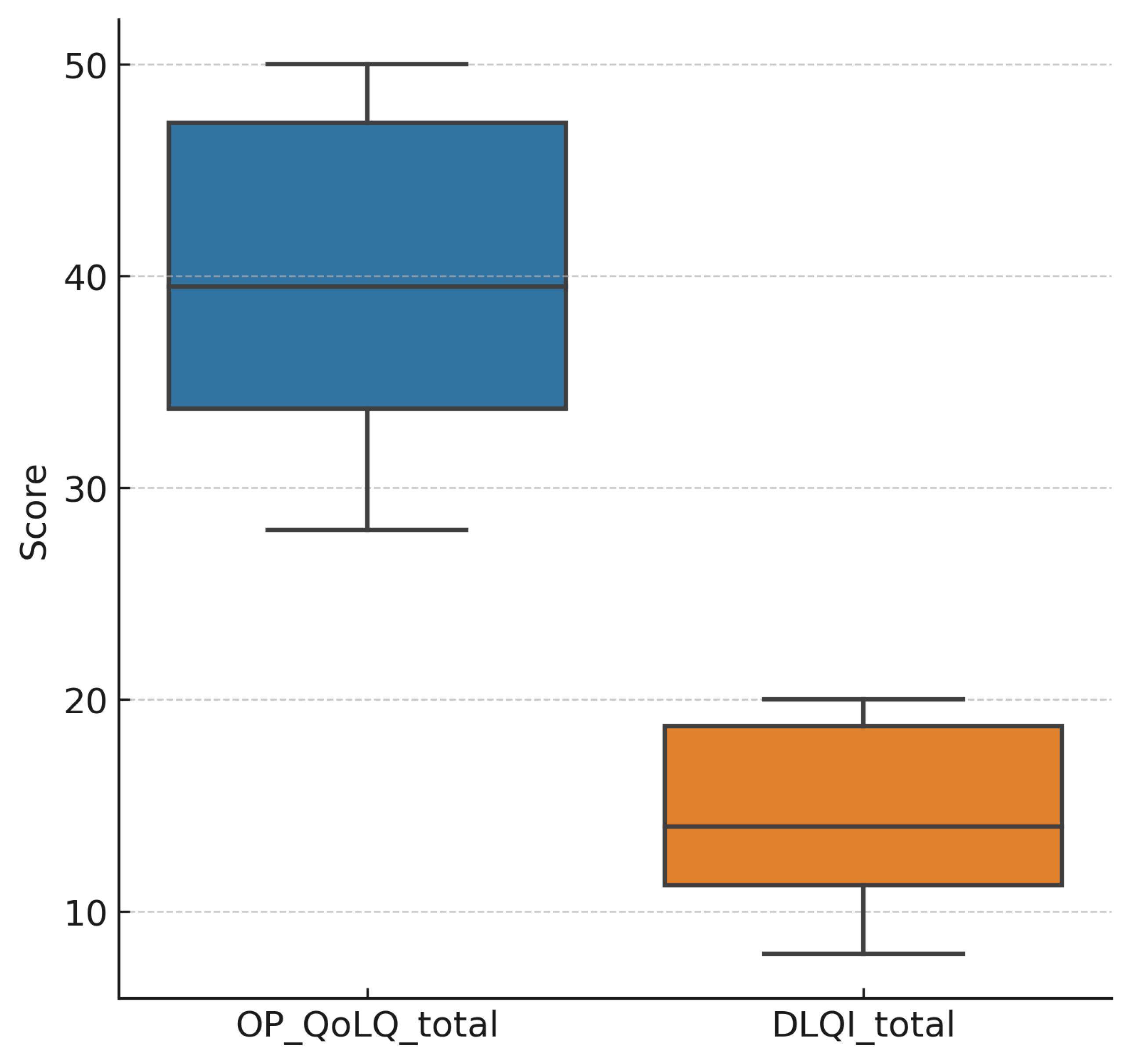

3.2. Patient-Reported Outcomes

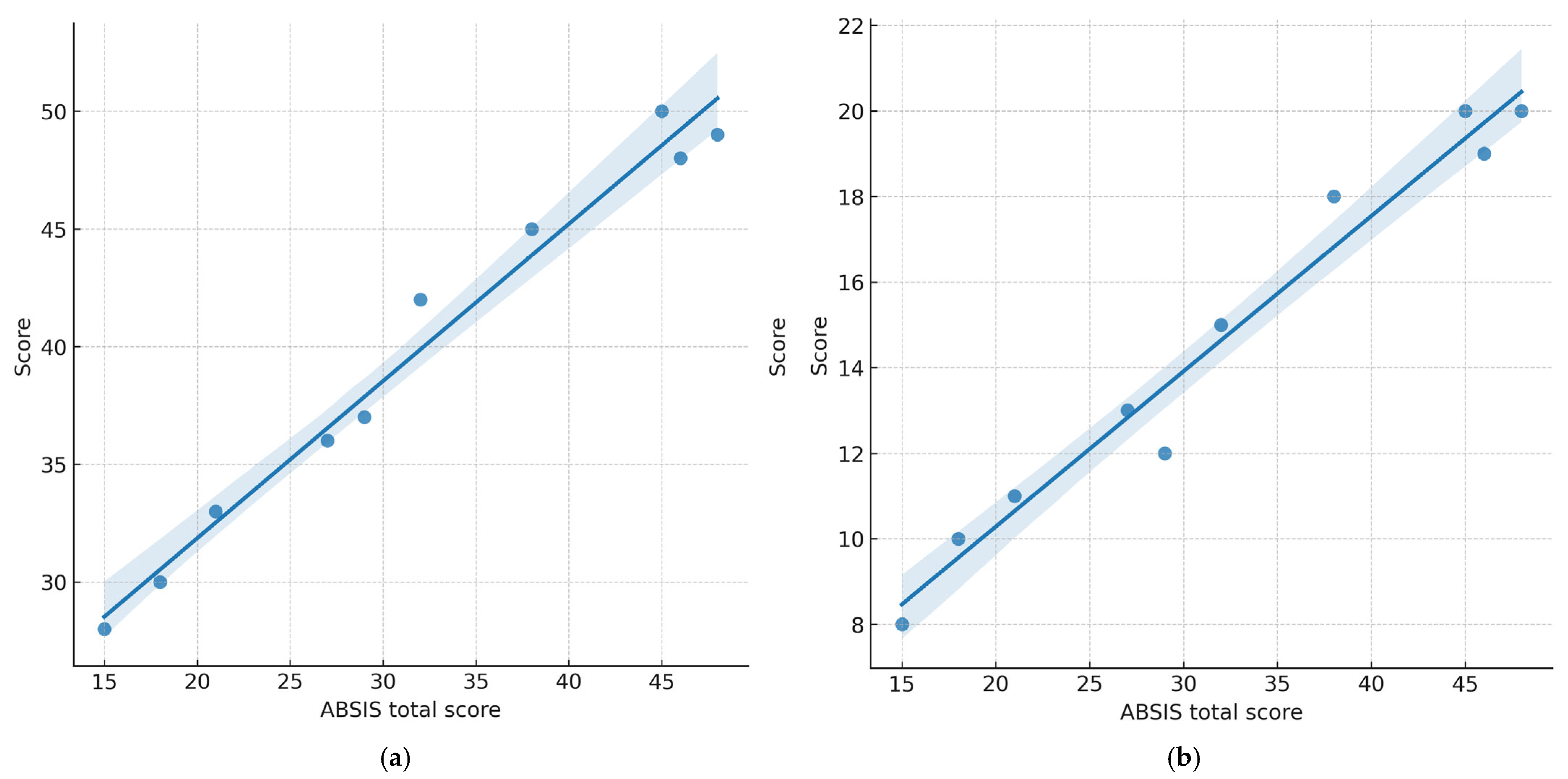

3.3. Correlation Between Disease Severity and Quality of Life

- ABSIS total vs. OP-QoLQ: ρ = 0.78, p = 0.008

- ABSIS total vs. DLQI: ρ = 0.71, p = 0.021

- ABSIS oral subscore vs. OP-QoLQ: ρ = 0.80, p = 0.006

- ABSIS oral subscore vs. DLQI: ρ = 0.74, p = 0.015

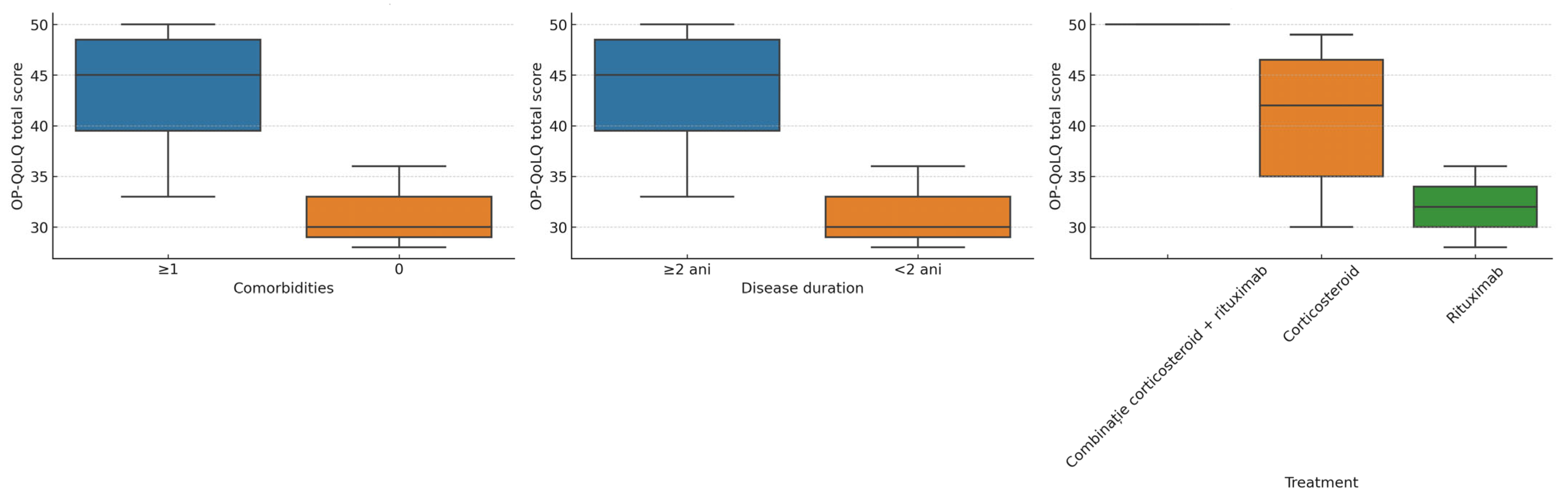

3.4. Subgroup Analyses

- Sex: No statistically significant differences in OP-QoLQ (p = 0.42) or DLQI (p = 0.38) between males and females.

- Comorbidity status: Participants with one or more comorbidities had significantly higher OP-QoLQ scores (41.5 ± 7.6) compared to those without comorbidities (28.0 ± 4.2, p = 0.041).

- Disease duration: Those with disease duration of ≥2 years had significantly higher OP-QoLQ scores (42.3 ± 6.5) than patients with disease duration of <2 years (31.4 ± 5.9, p = 0.038). DLQI showed a similar trend (p = 0.049).

- Treatment type: The highest impairment was observed in the combination therapy group, followed by corticosteroids alone. Patients receiving rituximab monotherapy had comparatively lower mean scores, although these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

3.5. Exploratory Regression Analyses

- OP-QoLQ model: Adjusted R2 = 0.62, p < 0.01

- DLQI model: Adjusted R2 = 0.58, p < 0.01

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Comparison with Existing Literature

4.3. Potential Biological and Clinical Explanations

4.4. Strengths and Unique Contribution

4.5. Implications for Clinical Practice and Health Policy

5. Future Research

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABSIS | Autoimmune Bullous Skin Disorder Intensity Score |

| DIF | Direct Immunofluorescence |

| DLQI | Dermatology Life Quality Index |

| Dsg1 | Desmoglein 1 |

| Dsg3 | Desmoglein 3 |

| ERN-Skin | European Reference Network on Rare and Complex Skin Diseases |

| OHRQoL | Oral Health–Related Quality of Life |

| OP-QoLQ | Oral Pemphigus–Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| PROs | Patient-reported outcomes |

| PV | Pemphigus vulgaris |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

References

- Lipsky, M.S.; Singh, T.; Zakeri, G.; Hung, M. Oral Health and Older Adults: A Narrative Review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albagieh, H.; Alhamid, R.F.; Alharbi, A.S. Oral Pemphigus Vulgaris: A Case Report with Review of Literature. Cureus 2023, 15, e48839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodszky, V.; Tamási, B.; Hajdu, K.; Péntek, M.; Szegedi, A.; Sárdy, M.; Bata-Csörgő, Z.; Kinyó, Á.; Gulácsi, L.; Rencz, F. Disease Burden of Patients with Pemphigus from a Societal Perspective. Exp. Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2021, 21, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V’lckova-Laskoska, M.T.; Laskoski, D.S.; Kamberova, S.; Caca-Biljanovska, N.; Volckova, N. Epidemiology of Pemphigus in Macedonia: A 15-Year Retrospective Study (1990–2004). Int. J. Dermatol. 2007, 46, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, C.J.; Sathe, N.C.; Khan, M.A.B. Pemphigus Vulgaris. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560860/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Tehranchi-Nia, Z.; Qureshi, T.A.; Ahmed, A.R. Pemphigus Vulgaris in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1998, 46, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlas, V.N.; Elian, V.; Varlas, G.R.; Bubulac, L.; Epistatu, D.; Peneș, O.; Pop, A.; Zetu, C.; Părlătescu, I. The current state of the pharmacotherapeutic approach in lichen planus of the oral and genital mucosa. Farmacia 2024, 72, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Corcuera, M.; Esparza-Gómez, G.; González-Moles, M.A.; Bascones-Martínez, A. Oral Ulcers: Clinical Aspects. A Tool for Dermatologists. Part II. Chronic Ulcers. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 34, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubulac, L.; Gheorghe, I.-R.; Ungureanu, E.; Bogdan-Andreescu, C.F.; Albu, C.-C.; Gheorghe, C.-M.; Mușat, O.; Eremia, I.A.; Panea, C.A.; Burcea, A. Promoting Re-Epithelialization in Diabetic Foot Wounds Using Integrative Therapeutic Approaches. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerninski, R.; Zadik, Y.; Kartin-Gabbay, T.; Zini, A.; Touger-Decker, R. Dietary Alterations in Patients with Oral Vesiculoulcerative Diseases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2014, 117, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heelan, K.; Mahar, A.L.; Walsh, S.; Shear, N.H. Pemphigus and Associated Comorbidities: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2015, 40, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, E.; Vielmuth, F.; Wanuske, M.T.; Seifert, M.; Pollmann, R.; Eming, R.; Waschke, J. Role of Dsg1- and Dsg3-Mediated Signaling in Pemphigus Autoantibody-Induced Loss of Keratinocyte Cohesion. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russu, E.-A.; Popa, L.G.; Burcea, A.; Bohîlţea, L.C.; Bogdan-Andreescu, C.F.; Bănățeanu, A.M.; Poalelungi, C.V.; Albu, C.-C. Genetic and Molecular Insights into Pemphigus Vulgaris with Oral Involvement: Implications for Biologic Therapy. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2025, 17, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetarayani, D.; Kahdina, M.; Waitupu, A.; Pratiwi, L.; Ningtyas, M.C.; Adytia, G.J.; Sutanto, H. Immunosenescence and the Geriatric Giants: Molecular Insights into Aging and Healthspan. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreescu, C.F.; Mihai, L.L.; Răescu, M.; Tuculină, M.J.; Cumpătă, C.N.; Ghergic, D.L. Age influence on periodontal tissues: A histological study. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2013, 54 (Suppl. S3), 811–815. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan-Andreescu, C.F.; Bănățeanu, A.-M.; Botoacă, O.; Defta, C.L.; Poalelungi, C.-V.; Brăila, A.D.; Damian, C.M.; Brăila, M.G.; Dȋră, L.M. Oral Wound Healing in Aging Population. Surgeries 2024, 5, 956–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoriou, S.; Efthymiou, O.; Stefanaki, C.; Rigopoulos, D. Management of Pemphigus Vulgaris: Challenges and Solutions. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 8, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandelwal, K.; Jajoo, V.; Bajpai, K.; Madke, B.; Prasad, R.; Wanjari, M.B.; Munjewar, P.K.; Taksande, A.B. Rituximab in Pemphigus Vulgaris: A Review of Monoclonal Antibody Therapy in Dermatology. Cureus 2023, 15, e40734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Rijt, L.J.M.; Stoop, C.C.; Weijenberg, R.A.F.; de Vries, R.; Feast, A.R.; Sampson, E.L.; Lobbezoo, F. The Influence of Oral Health Factors on the Quality of Life in Older People: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2020, 60, e378–e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, E.M.; Kossioni, A.; Fukai, K. Policies Supporting Oral Health in Ageing Populations Are Needed Worldwide. Int. Dent. J. 2022, 72, S27–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassel, A.J.; Danner, D.; Schmitt, M.; Nitschke, I.; Rammelsberg, P.; Wahl, H.W. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Is Linked with Subjective Well-Being and Depression in Early Old Age. Clin. Oral Investig. 2011, 15, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahm, S.H.; Yang, S. Associations between Systemic and Dental Diseases in Elderly Korean Population. Medicina 2024, 60, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Jung, D. Factors Influencing Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults in Rural Areas: Oral Dryness and Oral Health Knowledge and Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan-Andreescu, C.F.; Bănățeanu, A.M.; Albu, C.C.; Poalelungi, C.V.; Botoacă, O.; Damian, C.M.; Dȋră, L.M.; Albu, Ş.D.; Brăila, M.G.; Cadar, E.; et al. Oral Mycobiome Alterations in Postmenopausal Women: Links to Inflammation, Xerostomia, and Systemic Health. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, Ş.-D.; Suciu, I.; Albu, C.-C.; Dragomirescu, A.-O.; Ionescu, E. Impact of Malocclusions on Periodontopathogenic Bacterial Load and Progression of Periodontal Disease: A Quantitative Analysis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, S.M.; Gad, M.M.; Ellakany, P.; El Zayat, M.; AlGhamdi, M.; Abdelrahman, H.; El-Din, M.S. Impact of Prosthetic Rehabilitation on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Saudi Adults: A Prospective Observational Study with Pre–Post Design. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabolli, S.; Mozzetta, A.; Antinone, V.; Alfani, S.; Cianchini, G.; Abeni, D. The Health Impact of Pemphigus Vulgaris and Pemphigus Foliaceus Assessed Using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 158, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.; Hoffman, V.M.; Yale, M.; Strong, R.; Tomayko, M.M. Psychosocial Burden of Autoimmune Blistering Diseases: A Comprehensive Survey Study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H.; Stone, C.; Murrell, D.F. Scoring Criteria for Autoimmune Bullous Diseases: Utility, Merits, and Demerits. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2024, 15, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askin, O.; Ozkoca, D.; Kutlubay, Z.; Mat, M.C. A Retrospective Analysis of Pemphigus Vulgaris Patients: Demographics, Diagnosis, Co-Morbid Diseases and Treatment Modalities Used. North. Clin. Istanb. 2020, 7, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Jornet, P.; Camacho-Alonso, F.; Lucero-Berdugo, M. Measuring the Impact of Oral Mucosa Disease on Quality of Life. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2009, 19, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, A.Y.; Khan, G.K. The Dermatology Life Quality Index: A Simple Practical Measure for Routine Clinical Use. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1994, 19, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, S.Z.; Chams-Davatchi, C.; Daneshpazhooh, M.; Valikhani, M.; Esmaili, N. Quality of life and psychological status of patients with pemphigus vulgaris using Dermatology Life Quality Index and General Health Questionnaires. J. Dermatol. 2012, 39, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krain, R.L.; Kushner, C.J.; Tarazi, M.; Gaffney, R.G.; Yeguez, A.C.; Zamalin, D.E.; Pearson, D.R.; Feng, R.; Payne, A.S.; Werth, V.P. Assessing the correlation between disease severity indices and quality of life measurement tools in pemphigus. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hébert, V.; Boulard, C.; Houivet, E.; Duvert Lehembre, S.; Borradori, L.; Della Torre, R.; Feliciani, C.; Fania, L.; Zambruno, G.; Camaioni, D.B.; et al. Large international validation of ABSIS and PDAI pemphigus severity scores. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyshov, P.V.; Finlay, A.Y.; Patsatsi, A.; Marinović, B.; Salavastru, C.; Murrell, D.F.; Tomas-Aragones, L.; Poot, F.; Pustisek, N.; Svensson, A.; et al. Quality of Life Measurement in Autoimmune Blistering Diseases: Mutual Position Statement of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Task Forces on Quality of Life and Patient Oriented Outcomes and Autoimmune Blistering Diseases. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 34, 1666–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerninski, R.; Abu Elhawa, M.; Cleiman, M.; Keshet, N.; Haviv, Y.; Armoni-Weiss, G. Oral Involvement and Pain Among Pemphigus Vulgaris Patients as a Clinical Indicator for Management—An Epidemiological and Clinical Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshami, M.L.; Aswad, F.; Abdullah, B. A Clinical and Demographic Analysis of Oral Pemphigus Vulgaris: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study from 2001 to 2021. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.; Hathway, R.; Shipley, D.; Staines, K. The management of pemphigus vulgaris and mucous membrane pemphigoid in a joint oral medicine and dermatology clinic: A five-year narrative review. Br. Dent. J. 2024, 236, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgiç, A.; Aydın, F.; Sümer, P.; Keskiner, I.; Koç, S.; Bozkurt, S.; Mumcu, G.; Alpsoy, E.; Uzun, S.; Akman-Karakaş, A. Oral health related quality of life and disease severity in autoimmune bullous diseases. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 23, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmayanti, F.; Indrastiti, R.K.; Wimardhani, Y.S.; Jozerizal, S.; Suteja, D.E.; Handayani, R.; Wiriyakijja, P. Assessment of Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Oral Mucosal Diseases Using the Indonesian Version of the Chronic Oral Mucosal Disease Questionnaire-15 (COMDQ-15). Dent. J. 2024, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajla, A.; Meena, M.; Sareen, M.; Kumawat, O.; Saini, K.K.; Gulia, A.; Bhardwaj, K. Assessment of quality of life in patients with chronic oral mucosal diseases: A questionnaire-based study. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16 (Suppl. 4), S3996–S3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Cameron, M.C.; Garden, B.; Boers-Doets, C.B.; Schindler, K.; Epstein, J.B.; Choi, J.; Beamer, L.; Roeland, E.; Russi, E.G.; et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments of dermatologic adverse events associated with targeted cancer therapies. Support Care Cancer 2015, 23, 2231–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.; Ludwig, R.J.; Caux, F.; Payne, A.S.; Sadik, C.D.; Hashimoto, T.; Murrell, D.F. Editorial: Pemphigus and pemphigoid diseases: In memoriam Detlef Zillikens. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1426834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, S.; Durdu, M.; Akman, A.; Gunasti, S.; Uslular, C.; Memisoglu, H.R.; Alpsoy, E. Pemphigus in the Mediterranean region of Turkey: A study of 148 cases. Int. J. Dermatol. 2006, 45, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, P.; Maho-Vaillant, M.; Prost-Squarcioni, C.; Hebert, V.; Houivet, E.; Calbo, S.; Caillot, F.; Golinski, M.L.; Labeille, B.; Picard-Dahan, C.; et al. First-line rituximab combined with short-term prednisone versus prednisone alone for the treatment of pemphigus (Ritux 3): A prospective, multicentre, parallel-group, open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2031–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joly, P.; Horvath, B.; Patsatsi, A.; Uzun, S.; Bech, R.; Beissert, S.; Bergman, R.; Bernard, P.; Borradori, L.; Caproni, M.; et al. Updated S2K Guidelines for the Management of Pemphigus Vulgaris/Foliaceus and Bullous Pemphigoid. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 1900–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulikemu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q. Targeting Therapy in Pemphigus. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.M.; Tupchong, S.; Huang, S.; Are, A.; Hsu, S.; Motaparthi, K. An Updated Review of Pemphigus Diseases. Medicina 2021, 57, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, A.K.; Mülayim, M.K.; Gür, T.F.; Acar, A.; Bozca, B.C.; Ceylan, C.; Kılınç, F.; Güner, R.Y.; Albayrak, H.; Durdu, M.; et al. Evaluation of the quality of life and the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with pemphigus with oral mucosal involvement: A multicenter observational study. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2024, 14, e2024099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culton, D.A.; McCray, S.K.; Park, M.; Roberts, J.C.; Li, N.; Zedek, D.C.; Anhalt, G.J.; Cowley, D.O.; Liu, Z.; Diaz, L.A. Mucosal pemphigus vulgaris anti-Dsg3 IgG is pathogenic to the oral mucosa of humanized Dsg3 mice. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 1590–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, Z.H.; Jimenez, A.; Taliercio, V.L.; Clarke, J.T.; Hansen, C.B.; Hull, C.M.; Rhoads, J.L.W.; Zone, J.J.; Sahni, V.N.; Kean, J.; et al. Skin-Related Quality of Life During Autoimmune Bullous Disease Course. JAMA Dermatol. 2023, 159, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lernia, V.; Casanova, D.M.; Goldust, M.; Ricci, C. Pemphigus vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid: Update on diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2020, 10, e2020050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huo, T.; Lu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, W.; Chen, H. Recent Advances in Aging and Immunosenescence: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Cells 2025, 14, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welc, N.; Ważniewicz, S.; Głuszak, P.; Spałek, M.; Seraszek-Jaros, A.; Jałowska, M.; Dmochowski, M. Clinical Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Treatment in Patients with Pemphigus—A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Antibodies 2024, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, V.; Pérez-Alcaraz, L.; Belinchón-Romero, I.; Ramos-Rincón, J.-M. Comorbidities in Patients with Autoimmune Bullous Disorders: Hospital-Based Registry Study. Life 2022, 12, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egu, D.T.; Schmitt, T.; Waschke, J. Mechanisms causing acantholysis in pemphigus—Lessons from human skin. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 884067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.; Poelhekken, M.; Meijer, J.M.; Bolling, M.C.; Horváth, B. The positive impact of rituximab on the quality of life and mental health in patients with pemphigus. JAAD Int. 2022, 7, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R. Rituximab in pemphigus—Exploring the less frequently travelled terrains. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2025, 16, 537–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instrument | Domains Assessed | No. of Items | Scoring System | Interpretation | Recall Period | Adaptation & Validation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OP-QoLQ (Oral Pemphigus–Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire) | Physical symptoms, functional limitations, emotional well-being, social participation, treatment burden | 15 | 5-point Likert (0 = never to 4 = very often); total score range: 0–60 | 0–20 = mild impact; 21–40 = moderate impact; 41–60 = severe impact | 2 weeks | Minor linguistic adjustments to enhance comprehension among older adults; pilot pretesting conducted in older adults with oral pemphigus vulgaris to ensure cultural and linguistic appropriateness; no formal psychometric revalidation performed | López-Jornet et. al. [31] |

| DLQI (Dermatology Life Quality Index) | Symptoms & feelings, daily activities, leisure, work/school, personal relationships, treatment | 10 | 4-point Likert (0 = not at all to 3 = very much); total score range: 0–30 | 0–1 = no effect; 2–5 = small effect; 6–10 = moderate effect; 11–20 = very large effect; 21–30 = extremely large effect | 2 weeks | Inclusion of oral symptom–specific prompts to improve disease relevance; pilot pretesting for clarity and cultural appropriateness in older adult patients; no formal psychometric revalidation performed | Finlay et al. [32] |

| Variable | n (%)/Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.4 ± 5.9 | — |

| Female sex | 6 (60%) | — |

| Male sex | 4 (40%) | — |

| Disease duration (years) | — | 3.2 (1.8–5.4) |

| Comorbidities | 8 (80%) | — |

| Hypertension | 6 (60%) | — |

| Type 2 diabetes | 3 (30%) | — |

| Treatment type | — | — |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 7 (70%) | — |

| Rituximab | 2 (20%) | — |

| Combination therapy | 1 (10%) | — |

| Predictor | β (OP-QoLQ) | p-Value | β (DLQI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABSIS total score | 0.68 | 0.009 | 0.62 | 0.014 |

| Disease duration | 0.31 | 0.041 | 0.28 | 0.048 |

| Age | 0.12 | 0.276 | 0.09 | 0.314 |

| Sex (female) | 0.08 | 0.341 | 0.07 | 0.372 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Russu, E.-A.; Popa, L.G.; Păunică, S.; Bubulac, L.; Giurcăneanu, C.; Albu, C.-C. Patient-Reported Outcomes on Quality of Life in Older Adults with Oral Pemphigus. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222843

Russu E-A, Popa LG, Păunică S, Bubulac L, Giurcăneanu C, Albu C-C. Patient-Reported Outcomes on Quality of Life in Older Adults with Oral Pemphigus. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222843

Chicago/Turabian StyleRussu, Emily-Alice, Liliana Gabriela Popa, Stana Păunică, Lucia Bubulac, Călin Giurcăneanu, and Cristina-Crenguța Albu. 2025. "Patient-Reported Outcomes on Quality of Life in Older Adults with Oral Pemphigus" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222843

APA StyleRussu, E.-A., Popa, L. G., Păunică, S., Bubulac, L., Giurcăneanu, C., & Albu, C.-C. (2025). Patient-Reported Outcomes on Quality of Life in Older Adults with Oral Pemphigus. Healthcare, 13(22), 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222843