Patients and Communities Shape Regional Health Research Priorities: A Participatory Study from South Tyrol, Italy

Highlights

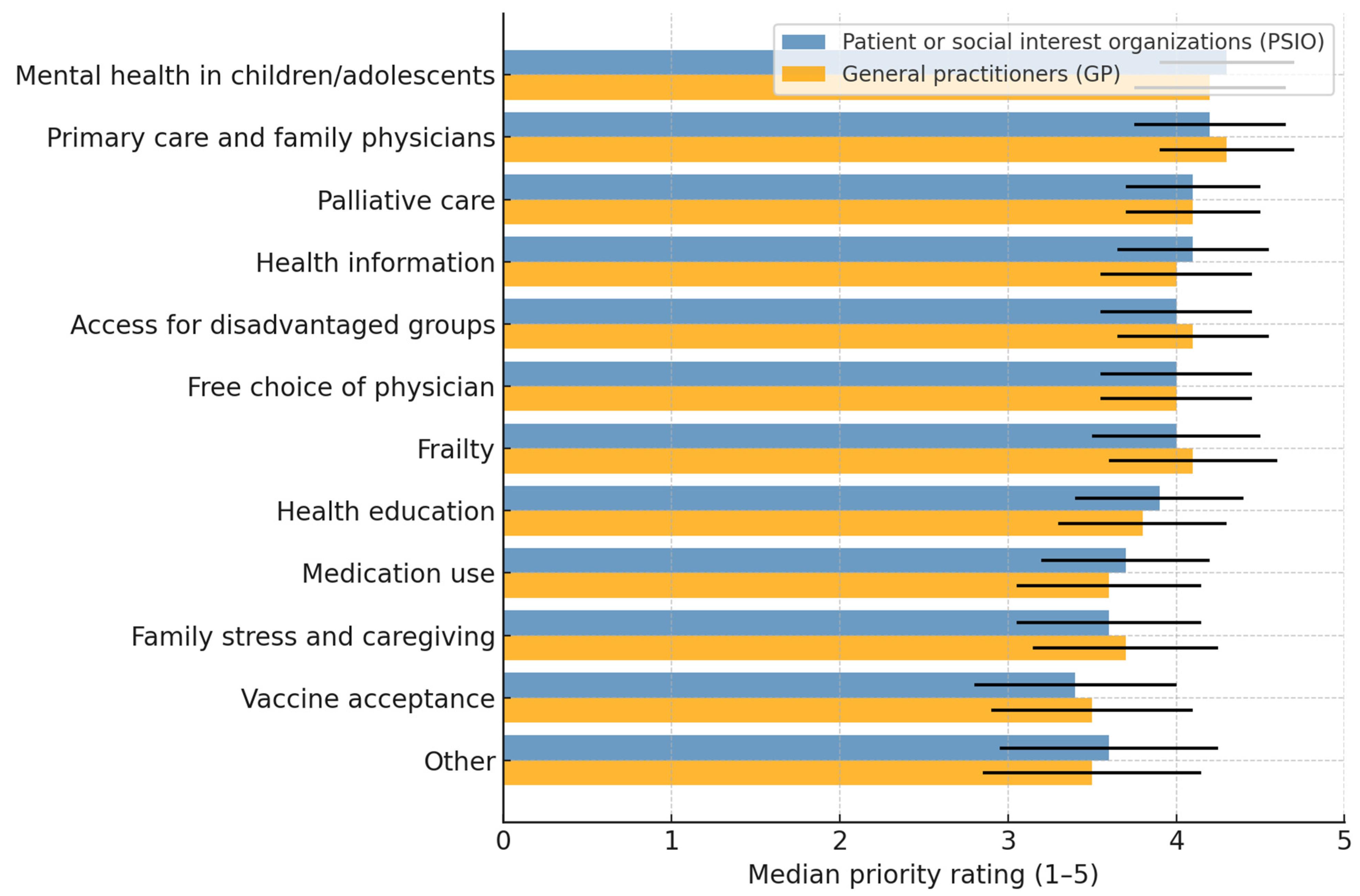

- Patient and social interest organizations identified research on the mental health of children and adolescents, continuity and trust in primary care, and patient-oriented palliative and end-of-life care as the top regional health services research priorities.

- General practitioners participated only marginally in regional health service research priority setting.

- Regional health research agendas should incorporate community-driven priorities to ensure their relevance and uptake.

- Strategies are needed to improve general practitioner engagement in regional health services research to complement the active participation of patients and social organizations.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Questionnaire Development and Content

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

3. Results

3.1. Survey Participation and Respondent Characteristics

3.1.1. Language of Open-Text Responses and Research Interest

3.1.2. Perceived Barriers to Healthcare Access

3.2. Research Priority Ratings

3.3. Interest in Research Participation

Correlation Results

3.4. Recommendations for Enhancing Patient and Public Involvement

3.4.1. Feeling Heard in Health Decisions and Research

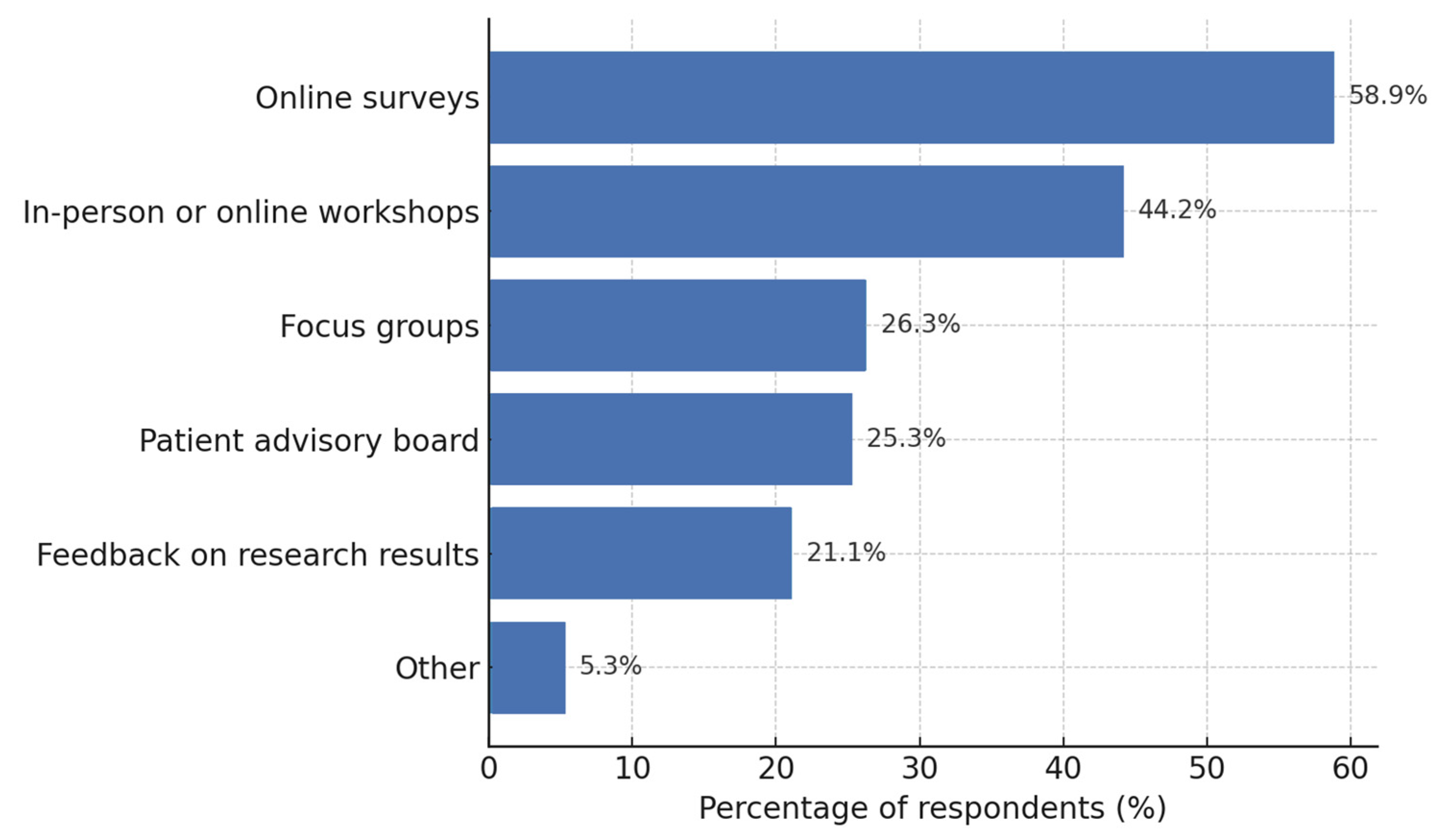

3.4.2. Preferred Modes of Participation in Setting Research Priorities

4. Discussion

4.1. Respondent Characteristics

4.2. Interpretation of Research Priority Patterns

4.3. Interpretation of Interest in Research Participation

4.4. Preferred Modes of Research Participation

4.5. Recommendations for Enhancing Research Participation

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GP | General practitioner |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| PSIO | Patient and social interest organization |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Boivin, A.; Lehoux, P.; Lacombe, R.; Burgers, J.; Grol, R. Involving Patients in Setting Priorities for Healthcare Improvement: A Cluster Randomized Trial. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manafò, E.; Petermann, L.; Vandall-Walker, V.; Mason-Lai, P. Patient and Public Engagement in Priority Setting: A Systematic Rapid Review of the Literature. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thumboo, J.; Yoon, S.; Wee, S.; Yeam, C.T.; Low, E.C.T.; Lee, C.E. Developing Population Health Research Priorities in Asian City State: Results from a Multi-Step Participatory Community Engagement. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacFarlane, A.; Phelan, H.; Papyan, A.; Hassan, A.; Garry, F. Research Prioritization in Migrant Health in Ireland: Toward a Participatory Arts-Based Paradigm for Academic Primary Care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2022, 20, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, B. Inclusion of Marginalized Groups and Communities in Global Health Research Priority-Setting. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2019, 14, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilahun, B.; Amare, G.; Endehabtu, B.F.; Atnafu, A.; Derseh, L.; Gurmu, K.K.; Delllie, E.; Nigusie, A. Explore the Practice and Barriers of Collaborative Health Policy and System Research-Priority Setting Exercise in Ethiopia. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2024, 22, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.; Fenton, M.; Hall, M.; Cowan, K.; Chalmers, I. Patients’, Clinicians’ and the Research Communities’ Priorities for Treatment Research: There Is an Important Mismatch. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2015, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A. Supporting Primary Care Communication on Vaccination in Multilingual and Culturally Diverse Settings: Lessons from South Tyrol, Italy. Epidemiologia 2025, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausserhofer, D.; Barbieri, V.; Lombardo, S.; Gärtner, T.; Eisendle, K.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A.; Wiedermann, C.J. Health Literacy Gaps Across Language Groups: A Population-Based Assessment in Alto Adige/South Tyrol, Italy. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergebnisse Sprachgruppenzählung—2024|Publikationen Und Verschiedene Statistiken Diverser Themen. Available online: https://astat.provincia.bz.it/de/publikationen/ergebnisse-sprachgruppenzahlung-2024 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Quinton, S.; Treveri Gennari, D.; Dibeltulo, S. Engaging Older People through Visual Participatory Research: Insights and Reflections. Qual. Res. 2023, 23, 1647–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.; Schulz, K.; Chenais, E. Can We Agree on That”? Plurality, Power and Language in Participatory Research. Prev. Vet. Med. 2020, 180, 104991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purschke, C. Crowdscapes. Participatory Research and the Collaborative (Re) Construction of Linguistic Landscapes with Lingscape. Lingv Vanguard. 2021, 7, 20190032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisenop, F.S.; Natan, M.N.; Lindert, J.L. Community-Based Participatory Research in Population-Based Health Surveys-a Case Example from East Friesland (Germany). Eur. J. Public. Health 2020, 30, ckaa165-954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loignon, C.; Hudon, C.; Goulet, É.; Boyer, S.; De Laat, M.; Fournier, N.; Grabovschi, C.; Bush, P. Perceived Barriers to Healthcare for Persons Living in Poverty in Quebec, Canada: The EQUIhealThY Project. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, P.; Tierney, E.; O’Carroll, A.; Nurse, D.; MacFarlane, A. Exploring Levers and Barriers to Accessing Primary Care for Marginalised Groups and Identifying Their Priorities for Primary Care Provision: A Participatory Learning and Action Research Study. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markey, K.; Noonan, M.; Doody, O.; Tuohy, T.; Daly, T.; Regan, C.; O’Donnell, C. Fostering Collective Approaches in Supporting Perinatal Mental Healthcare Access for Migrant Women: A Participatory Health Research Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turin, T.C.; Chowdhury, N.; Haque, S.; Rumana, N.; Rahman, N.; Lasker, M.A.A. Meaningful and Deep Community Engagement Efforts for Pragmatic Research and beyond: Engaging with an Immigrant/Racialised Community on Equitable Access to Care. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colizzi, M.; Lasalvia, A.; Ruggeri, M. Prevention and Early Intervention in Youth Mental Health: Is It Time for a Multidisciplinary and Trans-Diagnostic Model for Care? Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C.; Chanen, A.; Hodges, C.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Killackey, E. Designing and Scaling up Integrated Youth Mental Health Care. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Plagg, B.; Marino, P.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A. Fortifying the Foundations: A Comprehensive Approach to Enhancing Mental Health Support in Educational Policies Amidst Crises. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, M.T.; Bruns, E.J.; Lee, K.; Cox, S.; Coifman, J.; Mayworm, A.; Lyon, A.R. Rates of Mental Health Service Utilization by Children and Adolescents in Schools and Other Common Service Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2021, 48, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, K.; Fainman-Adelman, N.; Anderson, K.K.; Iyer, S.N. Pathways to Mental Health Services for Young People: A Systematic Review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 1005–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulany, A.; Stukel, T.A.; Kurdyak, P.; Fu, L.; Guttmann, A. Association of Primary Care Continuity with Outcomes Following Transition to Adult Care for Adolescents with Severe Mental Illness. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e198415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, R.; Endalamaw, A.; Erku, D.; Wolka, E.; Nigatu, F.; Zewdie, A.; Assefa, Y. Continuity and Care Coordination of Primary Health Care: A Scoping Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, S. Our Unrealized Imperative: Integrating Mental Health Care into Hospice and Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2025, 28, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalev, D.; Robbins-Welty, G.; Ekwebelem, M.; Moxley, J.; Riffin, C.; Reid, M.C.; Kozlov, E. Mental Health Integration and Delivery in the Hospice and Palliative Medicine Setting: A National Survey of Clinicians. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2024, 67, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaihlanen, A.-M.; Virtanen, L.; Buchert, U.; Safarov, N.; Valkonen, P.; Hietapakka, L.; Hörhammer, I.; Kujala, S.; Kouvonen, A.; Heponiemi, T. Towards Digital Health Equity—A Qualitative Study of the Challenges Experienced by Vulnerable Groups in Using Digital Health Services in the COVID-19 Era. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Beauchamp, A.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. Applying the Electronic Health Literacy Lens: Systematic Review of Electronic Health Interventions Targeted at Socially Disadvantaged Groups. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormacq, C.; Wosinski, J.; Boillat, E.; Van den Broucke, S. Effects of Health Literacy Interventions on Health-Related Outcomes in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Adults Living in the Community: A Systematic Review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormacq, C.; Oulevey Bachmann, A.; Van den Broucke, S.; Bodenmann, P. How Socioeconomically Disadvantaged People Access, Understand, Appraise, and Apply Health Information: A Qualitative Study Exploring Health Literacy Skills. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.A.; Wong, G.; Jones, A.P.; Steel, N. Access to Primary Care for Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Older People in Rural Areas: A Realist Review. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, A.; Siebelt, L.; Gavine, A.; Atkin, K.; Bell, K.; Innes, N.; Jones, H.; Jackson, C.; Haggi, H.; MacGillivray, S. Gypsy, Roma and Traveller Access to and Engagement with Health Services: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Public. Health 2018, 28, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mara-Eves, A.; Brunton, G.; Oliver, S.; Kavanagh, J.; Jamal, F.; Thomas, J. The Effectiveness of Community Engagement in Public Health Interventions for Disadvantaged Groups: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Public. Health 2015, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarin, W.; Sreetharan, S.; Doherty-Kirby, A.; Scott, M.; Zibrowski, E.; Soobiah, C.; Elliott, M.; Chaudhry, S.; Al-Khateeb, S.; Tam, C.; et al. Patient- and Public-Driven Health Research: A Model of Co-Leadership and Partnership in Research Priority Setting Using a Modified James Lind Alliance Approach. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2025, 181, 111731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heal, C.; Roberts, G. General Practice Research Priority Setting in Australia: Informing a Research Agenda to Deliver Best Patient Care. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2019, 48, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, R.; Blake, S. UK General Practice Service Delivery Research Priorities: An Adapted James Lind Alliance Approach. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2024, 74, e9–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milley, K.; Druce, P.; McNamara, M.; Bergin, R.J.; Chan, R.J.; Cust, A.E.; Davis, N.; Fishman, G.; Jefford, M.; Rankin, N.; et al. Cancer in General Practice Research Priorities in Australia. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2024, 53, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, A.F.; Warner, L.; Cuthbertson, L.; Sawatzky, R. Patient-Driven Research Priorities for Patient-Centered Measurement. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.-E.; Liang, M.-Y.; Zhang, E.-E.; Peng, Y.-Y.; Chen, L.-L.; Deng, J.-Y.; Lin, T.; Fu, J.; Zhang, J.-N.; Li, S.-L.; et al. Factors Influencing Willingness to Participate in Ophthalmic Clinical Trials and Strategies for Effective Recruitment. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 17, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, D.C.; Kelsall, H.L.; Slegers, C.; Forbes, A.B.; Loff, B.; Zion, D.; Fritschi, L. A Telephone Survey of Factors Affecting Willingness to Participate in Health Research Surveys. BMC Public. Health 2015, 15, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayet-Ageron, A.; Rudaz, S.; Perneger, T. Study Design Factors Influencing Patients’ Willingness to Participate in Clinical Research: A Randomised Vignette-Based Study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimundo-Silva, V.; Marques, C.T.; Fonseca, J.R.; Martínez-Silveira, M.S.; Reis, M.G. Factors Related to Willingness to Participate in Biomedical Research on Neglected Tropical Diseases: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0011996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.-E.; Li, M.-C. Factors Influencing the Willingness to Participate in Medical Research: A Nationwide Survey in Taiwan. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, J.M.; Jones, D.R.; Wen, C.K.F.; Materia, F.T.; Schneider, S.; Stone, A. Influence of Ecological Momentary Assessment Study Design Features on Reported Willingness to Participate and Perceptions of Potential Research Studies: An Experimental Study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Margolis, M.; McCormack, L.; LeBaron, P.A.; Chowdhury, D. What Affects People’s Willingness to Participate in Qualitative Research? An Experimental Comparison of Five Incentives. Field Methods 2017, 29, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicucci, M.; Dall’Oglio, I.; Biagioli, V.; Gawronski, O.; Piga, S.; Ricci, R.; Angelaccio, A.; Elia, D.; Fiorito, M.E.; Marotta, L.; et al. Participation of Nurses and Allied Health Professionals in Research Activities: A Survey in an Academic Tertiary Pediatric Hospital. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenke, R.; Mickan, S. The Role and Impact of Research Positions within Health Care Settings in Allied Health: A Systematic Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawo, S.; Gasser, S.; Gemperli, A.; Merlo, C.; Essig, S. General Practitioners’ Willingness to Participate in Research: A Survey in Central Switzerland. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, N.N.; Stewart, D.; Tierney, T.; Worrall, A.; Smith, M.; Elliott, J.; Beecher, C.; Devane, D.; Biesty, L. Sharing Space at the Research Table: Exploring Public and Patient Involvement in a Methodology Priority Setting Partnership. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2023, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virnau, L.; Braesigk, A.; Deutsch, T.; Bauer, A.; Kroeber, E.S.; Bleckwenn, M.; Frese, T.; Lingner, H. General Practitioners’ Willingness to Participate in Research Networks in Germany. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2022, 40, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.; Smyth, J.D.; Wood, H.M. Does Giving People Their Preferred Survey Mode Actually Increase Survey Participation Rates? An Experimental Examination. Public. Opin. Q. 2012, 76, 611–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, J.; De Bruijne, M. Willingness of Online Respondents to Participate in Alternative Modes of Data Collection. Surv. Pract. 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkyekyer, J.; Clifford, S.A.; Mensah, F.K.; Wang, Y.; Chiu, L.; Wake, M. Maximizing Participant Engagement, Participation, and Retention in Cohort Studies Using Digital Methods: Rapid Review to Inform the Next Generation of Very Large Birth Cohorts. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romsland, G.I.; Milosavljevic, K.L.; Andreassen, T.A. Facilitating Non-Tokenistic User Involvement in Research. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2019, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.; Mayers, S.; Goggins, K.; Schlundt, D.; Bonnet, K.; Williams, N.; Alcendor, D.; Barkin, S. Assessing Research Participant Preferences for Receiving Study Results. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2019, 4, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, K.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Scholz, B. From Member Checking to Collaborative Reflection: A Novel Way to Use a Familiar Method for Engaging Participants in Qualitative Research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2024, 21, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staley, K.; Barron, D. Learning as an Outcome of Involvement in Research: What Are the Implications for Practice, Reporting and Evaluation? Res. Involv. Engagem. 2019, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.; Clarke, M.; Staniszewska, S.; Chu, L.; Tembo, D.; Kirkpatrick, M.; Nelken, Y. Patient and Public Involvement in Research: A Journey to Co-Production. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, B.; Farmer, L.; Cooper, S.; von Wagner, C.; Friedrich, B.; Abel, G.A.; Spencer, A.; Cockcroft, E. Patient Bridge Role: A New Approach for Patient and Public Involvement in Healthcare Research Programmes. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e094521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, D.-W.; van Meeteren, K.; Klem, M.; Alsem, M.; Ketelaar, M. Designing a Tool to Support Patient and Public Involvement in Research Projects: The Involvement Matrix. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2020, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liabo, K.; Boddy, K.; Bortoli, S.; Irvine, J.; Boult, H.; Fredlund, M.; Joseph, N.; Bjornstad, G.; Morris, C. Public Involvement in Health Research: What Does “good” Look like in Practice? Res. Involv. Engagem. 2020, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoddinott, P.; Pollock, A.; O’Cathain, A.; Boyer, I.; Taylor, J.; MacDonald, C.; Oliver, S.; Donovan, J.L. How to Incorporate Patient and Public Perspectives into the Design and Conduct of Research. F1000Res 2018, 7, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.; Siddiqi, N.; Twiddy, M.; Kenyon, R. Patient and Public Involvement in Health Research in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, S.; Fitzgibbon, J.; Tonks, A.J.; Forty, L. Diversity in Patient and Public Involvement in Healthcare Research and Education-Realising the Potential. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e13896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheson, M.; Skinner, I.W.; Vehagen, A.; Auliffe, S.M.; Malliaras, P. Barriers and Enablers of Primary Healthcare Professionals in Health Research Engagement: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Nurs. Health Sci. 2025, 27, e70022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staniszewska, S.; Denegri, S.; Matthews, R.; Minogue, V. Reviewing Progress in Public Involvement in NIHR Research: Developing and Implementing a New Vision for the Future. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e017124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, R.; Martin-Kerry, J.; Hudson, J.; Parker, A.; Bower, P.; Knapp, P. Why Do Patients Take Part in Research? An Overview of Systematic Reviews of Psychosocial Barriers and Facilitators. Trials 2020, 21, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Priority Topic 1 | Rank by Mean | n (Valid) 2 | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health of children and adolescents | 1 | 87 | 4.29 (1.01) | 5.0 (4–5) |

| Continuity and trust in primary care | 2 | 88 | 4.15 (1.07) | 5.0 (4–5) |

| Patient-oriented palliative and end-of-life care | 3 | 85 | 4.11 (1.02) | 4.0 (4–5) |

| Trustworthy health information and communication | 4 | 89 | 4.09 (1.16) | 5.0 (4–5) |

| Access to healthcare for disadvantaged groups | 5 | 84 | 4.02 (1.13) | 4.0 (4–5) |

| Impact of free choice of a trusted GP on waiting times for specialist appointments and diagnostic procedures | 6 | 87 | 4.00 (1.19) | 5.0 (4–5) |

| Detection of frailty in older age and appropriate care | 7 | 89 | 3.96 (1.17) | 4.0 (3–5) |

| Health education in schools | 8 | 89 | 3.91 (1.14) | 4.0 (3–5) |

| Environmentally sustainable and safe prescription of medicines | 9 | 86 | 3.69 (1.20) | 4.0 (3–5) |

| Family consequences of gender differences in coping with stress/psychological burden) | 10 | 85 | 3.58 (1.23) | 4.0 (3–4) |

| Vaccine acceptance and culturally sensitive information | 11 | 87 | 3.44 (1.37) | 4.0 (2–4) |

| Other topics specified in free text 3 | — | 19 | 3.63 (1.80) | 5.0 (2–5) |

| Variables | n (Pairs) | ρ (Spearman) * | p-Value | Effect Size † |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interest in research participation × Palliative care priority | 73 | −0.23 | 0.049 | Small |

| Interest in research participation × Primary care continuity | 75 | −0.26 | 0.022 | Small |

| Interest in research participation × Stress in families | 73 | −0.25 | 0.034 | Small |

| Frailty × Palliative care | 84 | 0.66 | <0.001 | Large |

| Health education in schools × Stress in families | 82 | 0.59 | <0.001 | Large |

| Primary care continuity × Appropriate prescribing | 85 | 0.64 | <0.001 | Large |

| Frailty × Primary care continuity | 84 | 0.46 | <0.001 | Moderate |

| Frailty × Appropriate prescribing | 84 | 0.44 | <0.001 | Moderate |

| Palliative care × Primary care continuity | 83 | 0.48 | <0.001 | Moderate |

| Palliative care × Appropriate prescribing | 82 | 0.45 | <0.001 | Moderate |

| Health education in schools × Mental health of children | 85 | 0.42 | <0.001 | Moderate |

| Access for disadvantaged groups × Primary care continuity | 83 | 0.39 | 0.002 | Moderate |

| Access for disadvantaged groups × Appropriate prescribing | 82 | 0.37 | 0.003 | Moderate |

| Improvement Category 1 | n | % of Respondents 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Clearer communication | 12 | 12.6% |

| More time for participation | 10 | 10.5% |

| Active inclusion of patients/community | 7 | 7.4% |

| Representation in formal governance bodies | 5 | 5.3% |

| Greater recognition of GPs | 5 | 5.3% |

| Better education and information | 4 | 4.2% |

| Greater empathy from institutions | 3 | 3.2% |

| Improved accessibility/barrier-free opportunities | 3 | 3.2% |

| Reduction in bureaucratic barriers | 2 | 2.1% |

| Increased trust in health authorities/researchers | 2 | 2.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Mahlknecht, A.; Felderer, C.; Piccoliori, G.; Hager von Strobele-Prainsack, D.; Engl, A. Patients and Communities Shape Regional Health Research Priorities: A Participatory Study from South Tyrol, Italy. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2797. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212797

Wiedermann CJ, Barbieri V, Mahlknecht A, Felderer C, Piccoliori G, Hager von Strobele-Prainsack D, Engl A. Patients and Communities Shape Regional Health Research Priorities: A Participatory Study from South Tyrol, Italy. Healthcare. 2025; 13(21):2797. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212797

Chicago/Turabian StyleWiedermann, Christian J., Verena Barbieri, Angelika Mahlknecht, Carla Felderer, Giuliano Piccoliori, Doris Hager von Strobele-Prainsack, and Adolf Engl. 2025. "Patients and Communities Shape Regional Health Research Priorities: A Participatory Study from South Tyrol, Italy" Healthcare 13, no. 21: 2797. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212797

APA StyleWiedermann, C. J., Barbieri, V., Mahlknecht, A., Felderer, C., Piccoliori, G., Hager von Strobele-Prainsack, D., & Engl, A. (2025). Patients and Communities Shape Regional Health Research Priorities: A Participatory Study from South Tyrol, Italy. Healthcare, 13(21), 2797. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212797