Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Early palliative care in hematologic malignancies improves symptoms and quality of life, while reducing hospitalizations, transfusions, and chemotherapy near the end-of-life.

- Early referral is associated with lower healthcare costs and a shift in the place of death from hospital to home or hospice.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- These results support integrating early palliative care into standard hematology practice.

- Wider implementation could improve patient outcomes, reduce burdensome treatments, and optimize healthcare resource use.

Abstract

Background: Patients with hematologic malignancy (HM) experience high symptom burden (SB) and diminished quality of life (QOL). While early palliative care (EPC) benefits solid tumors, its impact in HM remains uncertain. Objectives: To systematically review the effects of EPC on patient-centered outcomes in individuals with HM. Methods: MEDLINE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Scopus were searched for English-language articles published between 2020 and 2024. Eligible studies included adults with advanced HM receiving EPC compared with usual care, reporting outcomes on SB, QOL, place of death (POD), healthcare costs (HCCs), or healthcare utilization (HCU). All original study designs were considered. Critical appraisal was performed, and results were synthesized narratively. The review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251019687). Results: Twelve studies were included, most of high quality (n = 10) and mainly conducted in America and Europe. Collectively, they enrolled 42,053 participants, largely with advanced disease, poor performance status, or limited prognosis. EPC consistently improved SB, particularly pain, appetite, and functional well-being, although results for anxiety and depression were inconsistent. Findings for QOL were mixed. EPC was associated with higher likelihood of home or hospice death. One study demonstrated substantial cost savings with home-based EPC. Across several studies, EPC was linked to lower HCU, including fewer transfusions, reduced chemotherapy near the end-of-life, and fewer aggressive interventions, hospitalizations, and intensive care admissions. Conclusions: EPC improves SB, influences POD, and reduces HCCs and HCU in HM. Evidence for QOL and psychological outcomes remains inconclusive. Further high-quality research is required to consolidate these findings.

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

Cancer is a major global health concern, with incidence rates rising worldwide. Hematologic malignancy (HM) accounts for around 6.5% of all cancers globally, and about 9.0% in both the United States of America and Europe [1]. The National Institutes of Health defines HM as cancers that originate in blood-forming tissue, such as the bone marrow, or in the cells of the immune system. This heterogeneous group of diseases displays substantial variation in illness trajectories, treatment strategies and potential for cure [2].

Historically, HM has been at the forefront of cancer treatment innovation, resulting in improved therapeutic outcomes and survival rates. Nevertheless, many patients continue to experience significant symptom burden, adverse effects of chemotherapy, relapsed disease, and ultimately death from their malignancy. These challenges make them appropriate candidates for early palliative care (EPC), either alongside or independent of active cancer treatment, to achieve effective symptom control and enhance quality of life (QOL) [3,4].

The concept of palliative care (PC) has evolved in recent years. Once focused primarily on end-stage cancer, PC now encompasses the care of all life-limiting conditions [5]. The World Health Organization defines PC as an approach that improves the QOL of patients and their families facing life-threatening illness, through early identification, comprehensive assessment, and management of pain and other physical, psychological, and spiritual problems [6]. This multidisciplinary model promotes well-being at any stage of disease, regardless of prognosis [6].

PC has been associated with improved QOL, reduced symptom burden, and decreased psychological distress [3]. However, patients with HM are less likely to access PC than those with solid tumors and are more likely to receive aggressive EOL care [7,8,9,10], and to die in intensive care units (ICU) [7]. Patients with HM are disproportionately likely to die in hospital, yet emerging evidence suggests that EPC may reduce hospital deaths and increase home/hospice deaths—shown in other serious illnesses—supporting its relevance to place of death (POD) in HM [4,11,12]. Emerging evidence also suggests that EPC can lower healthcare costs (HCCs)—particularly with early inpatient or home-based models and near the end-of-life (EOL)—although effects may vary by timeframe and setting [13,14,15,16,17]. Additionally, EPC is associated with reduced healthcare utilization (HCU)—e.g., shorter time per patient, fewer transfusions, less chemotherapy, and fewer ICU admissions, hospitalizations, and emergency department (ED) visits [13,18]—with similar patterns reported in other serious illnesses [11,15,19,20].

Several barriers to PC integration in HM have been identified, including the difficulty in defining the terminal phase of these diseases [21], common misconceptions equating PC with EOL care [22], strong patient-physician relationships within hematology teams, and the continuous emergence of novel treatments [23]. As a result, PC research in HM lags that of solid tumors. Additional investigation is needed to clarify the role of EPC in this patient population.

1.2. Objectives

This study aimed to systematically review and synthesize the available evidence on the associations between EPC and patient-centered outcomes among individuals with HM. Specifically, it examined how EPC relates to QOL, symptom control/burden (SCB), POD, HCU, and HCCs in this population.

2. Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the “Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions” [24], which informed the development of the search strategy, study selection, data extraction, critical appraisal, and synthesis processes. Reporting followed the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) guidelines [25].

A protocol was developed before screening and guided all stages of the review. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD420251019687); registration was submitted on 25 March 2025 and accepted on 26 March 2025, after title/abstract screening had begun but before full-text data extraction and synthesis. No changes were made to the prespecified objectives, eligibility criteria, outcomes (QOL, SCB, POD, HCU, HCCs), or synthesis plan after registration.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

Participants: Adults (≥18 years) with advanced HM (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma).

Intervention: EPC delivered concurrently with or in addition to active cancer treatment. Any definition of “early palliative care” as provided by the original study authors was accepted.

Comparator: Usual care without early integration of PC, including delayed or no PC.

Outcomes: Primary outcomes: QOL and SCB; Secondary outcomes: POD, HCCs, and HCU.

Study Design: All study designs were considered, except for reviews, editorials, letters, opinion pieces, academic theses, protocols without results, congress posters or abstracts reporting only preliminary findings, and commentaries.

Only English-language records were eligible. Full texts unavailable via our institutional subscriptions were excluded. We did not pursue interlibrary loans or contact authors for access.

2.2. Information Sources

We searched MEDLINE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Scopus for articles published between 11 September 2020, and 19 July 2024. All databases were last searched on 20 July 2024. The search start date was chosen because a prior systematic review included studies through 10 September 2020 [26]. Building on that work, the present review focuses specifically on EPC timing (as opposed to specialty PC in general) and updates the evidence through July 2024 with pre-specified primary outcomes (QOL, SCB) and secondary outcomes (POD, HCU, HCCs). This scope allows us to examine whether earlier PC integration is associated with differences in patient-centered outcomes and resource use beyond what was previously reported. An updated review within a short interval was justified by (i) the emergence of home-based/embedded EPC models and digital electronic patient-reported outcomes (e-PRO) platforms in HM care after 2020; and (ii) publication of newer studies (e.g., large utilization analyses, clinic-based EPC cohorts) with endpoints aligned to our pre-specified outcomes (QOL, SCB, POD, HCU, HCCs). Collectively, these developments warranted a focused EPC update beyond the timeframe and scope of Elliott et al. [26].

2.3. Search Strategy

The search strategy included the following terms: (early OR timely OR refer*) AND (“palliative care” OR “hospice care” OR “end of life care” OR “terminal care”) AND (“hematolog* malignanc*” OR “blood cancer*” OR “bone marrow cancer” OR leukemia OR lymphoma OR myeloma) NOT review. Filters were applied for: Language: English; Population: Adults aged ≥ 19 years; Publication date: 11 September 2020, to 19 July 2024.

The full electronic search strategy for all four databases is presented in Supplementary Table S1.

2.4. Selection Process

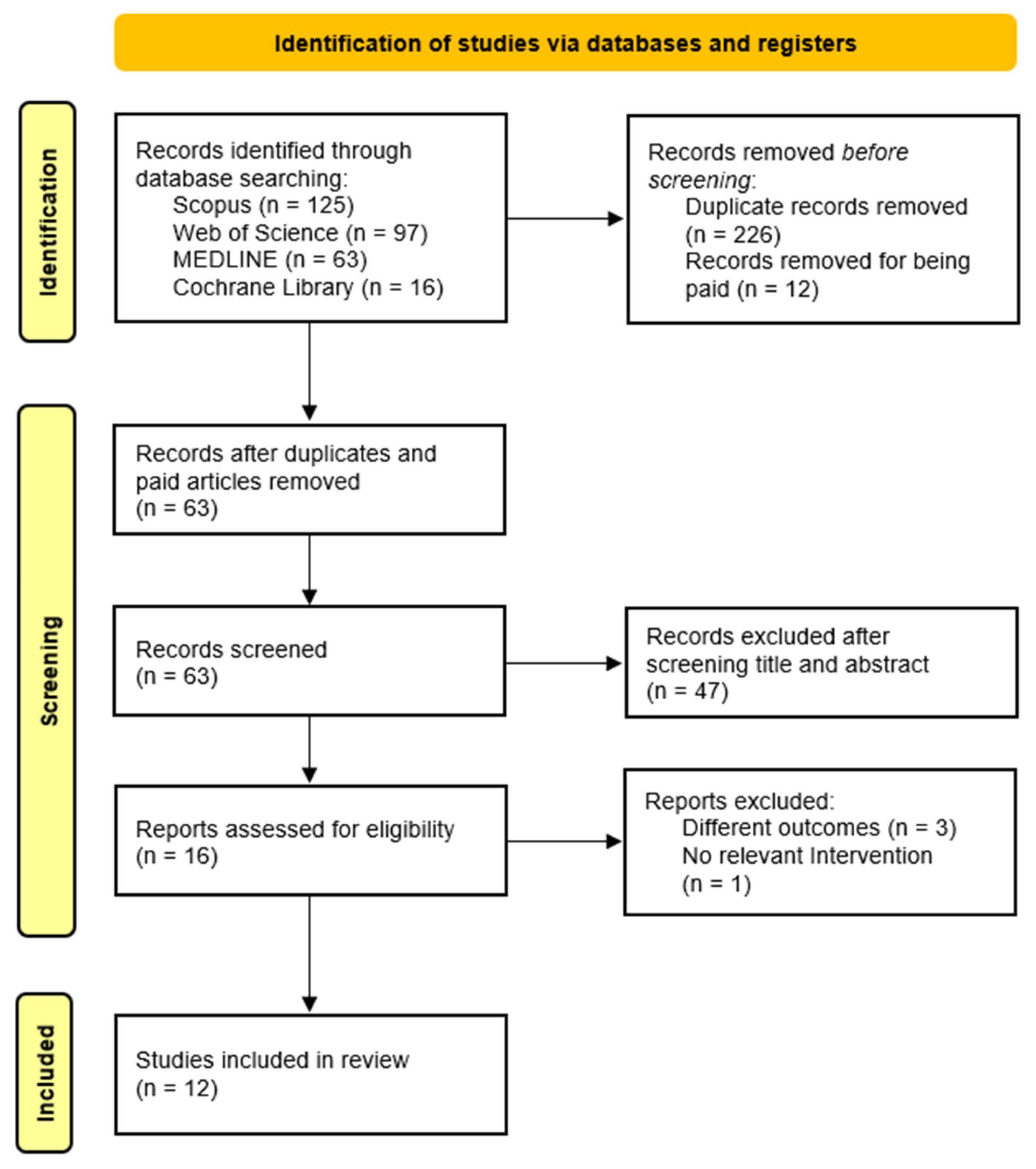

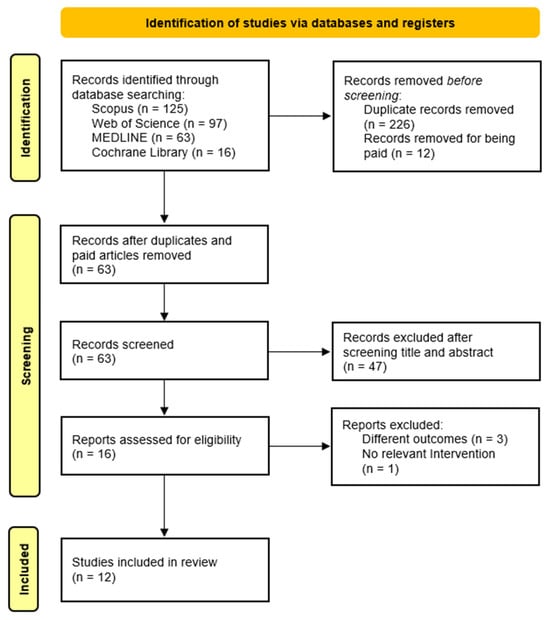

Following the initial search using the predefined headings and filters, two independent researchers screened the titles and abstracts of identified articles. Full texts were then reviewed for eligibility based on study design, objectives, population, and outcomes. Studies meeting all inclusion criteria were selected for review. Any disagreements during study selection or data extraction were resolved through discussion and consensus between the authors. See Figure 1 for the study selection process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

2.5. Data Collection Process

Two reviewers independently extracted data using a standardized, pre-piloted extraction form (spreadsheet template). The form captured: bibliographic details; country/setting; study design; population/disease subtype; sample size and follow-up; EPC model and timing; comparator; outcomes (QOL, SCB, POD, HCU, HCCs); measurement tools/scales; and key results relevant to the review question. After independent extraction, records from each study were compared side-by-side. Any differences in content or coding were discussed and resolved by consensus, with reference to the full text and prespecified definitions. A simple change log was maintained to document reconciliations and corrections. For verification, one reviewer cross-checked all critical numeric fields (e.g., sample sizes, counts, effect numbers reported in text/tables/figures) against the source article; the second reviewer verified corrections before finalization. No automation tools were used, and authors were not contacted for additional information. No formal inter-rater reliability statistic (e.g., kappa) was calculated; full agreement was reached through discussion.

2.6. Data Items

Data were collected for the following outcomes: QOL, SCB, POD, HCCs, and HCU. All outcome-related results reported in each study, irrespective of the measurement tools used, were included. Additional variables extracted comprised article characteristics (authors, country of origin, year of publication); study design and objectives; intervention details and duration; participant characteristics and type of HM; outcomes assessed, scales/tools applied, and key findings. In addition, we recorded how “early” or “timely” PC was defined by the original authors.

2.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias for each included study. After independent evaluation, the reviewers compared their assessments and discussed any discrepancies in judgment or scoring. Differences were resolved through structured discussion and mutual agreement, referring back to the study report and the appraisal tool criteria when needed. No third reviewer was involved, and no formal inter-rater statistic was calculated. For randomized controlled trial(s) (RCT), the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool was used [27]. For non-randomized studies, the ROBINS-I tool was applied [28]. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists were used to appraise cohort studies [29], cross-sectional [30], and qualitative studies [31]. Case reports were assessed using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist [32]. Each domain was evaluated according to the guidance and algorithms of the respective tools. No automation tools were used.

2.8. Effect Measures

For each outcome, the effect measures reported by the original study authors were accepted and used in both the synthesis and presentation of results.

2.9. Synthesis Methods

Given the limited number of eligible studies and the substantial heterogeneity in participants, interventions, and outcomes, neither meta-analysis nor meta-regression was undertaken. Instead, the evidence was synthesized narratively. No formal evidence grading framework was applied.

Definitions of EPC were extracted and interpreted as reported by the original authors, with attention to timing relative to diagnosis and patients’ clinical context. To enhance clarity, data were charted, grouped, and synthesized across the following categories: definitions of EPC, QOL, SCB, POD, HCCs, and HCU. Additionally, a summary across outcomes was prepared to concisely integrate the main patterns emerging across all outcomes, highlighting consistent and divergent findings.

We used four standardized, pre-piloted charting/extraction forms (Excel templates) to ensure consistent recording and reporting:

- Study Characteristics form—bibliographic details; country/setting; design; population/HM subtype; sample size and follow-up; EPC model and timing; comparator. (Feeds Table 1)

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies (n = 12).

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies (n = 12). - EPC Operationalization form—working definition of EPC in each study; EPC components (e.g., symptom management, goals-of-care discussions); team composition; care setting (inpatient/outpatient/home); frequency/intensity; timing criteria. (Feeds Table 2)

Table 2. Definition of “early palliative care” in the included studies (n = 12).

Table 2. Definition of “early palliative care” in the included studies (n = 12). - Outcome Extraction form—for each prespecified outcome (QOL, SCB, POD, HCU, HCCs): instrument/scale used, measurement timepoints, direction of effect, and numerical results where available (estimates/percentages/events). (Feeds Table 3)

Table 3. Main findings of the individual studies (n = 12).

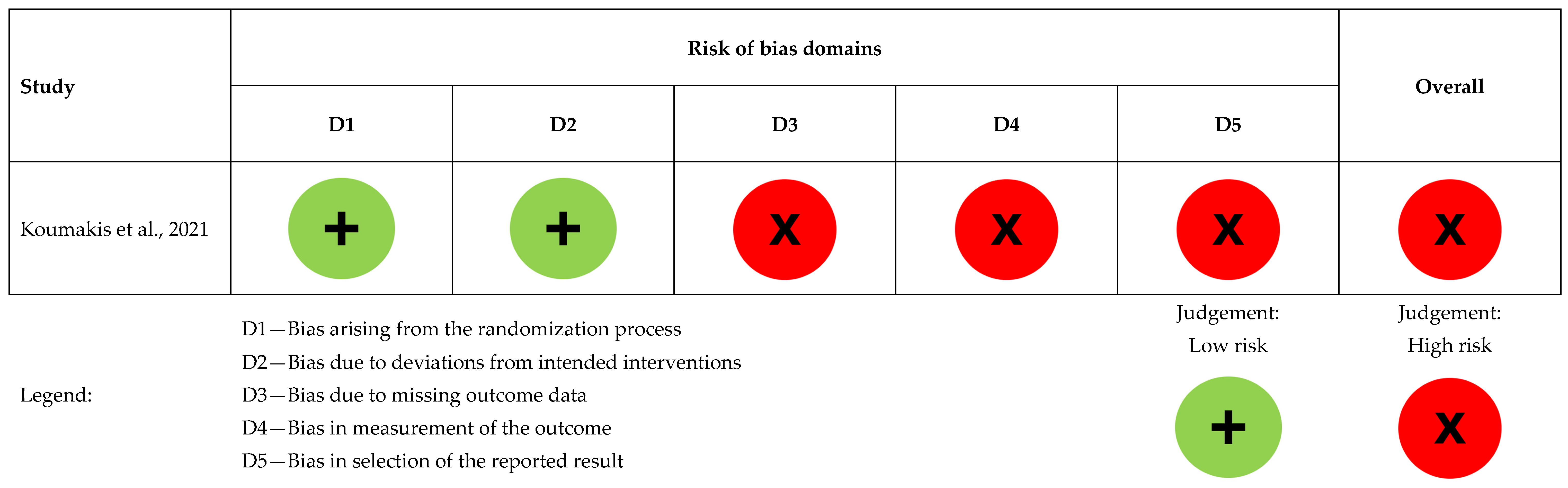

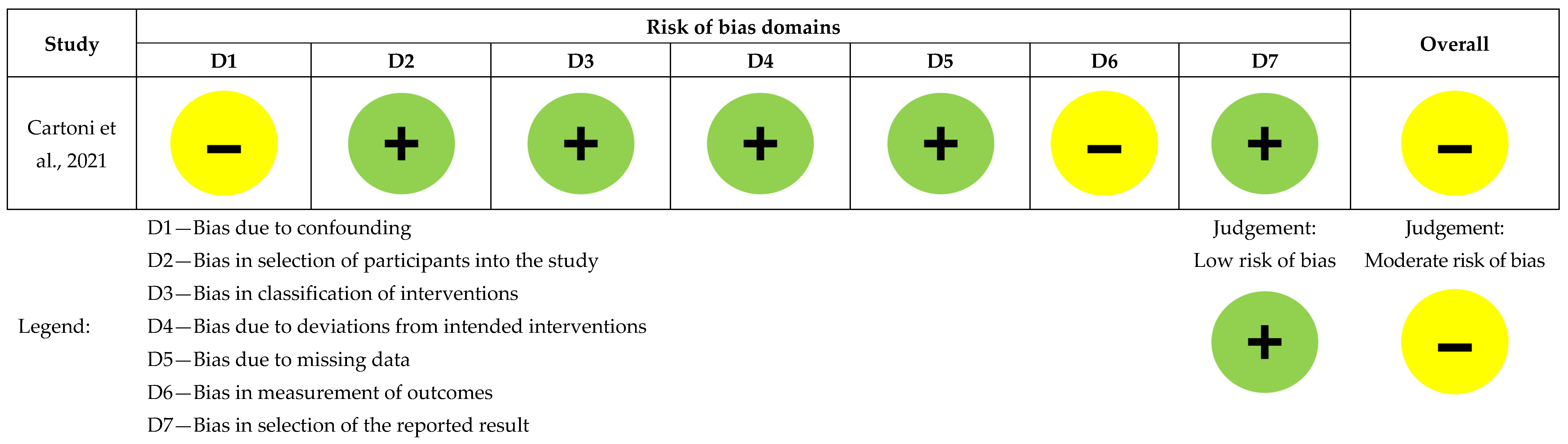

Table 3. Main findings of the individual studies (n = 12). - Risk of Bias form—design-specific item checklists mirroring the criteria of the appraisal tool used for each design, plus an overall judgement and rationale. (Feeds Figure 2 and Figure 3, and Table 4)

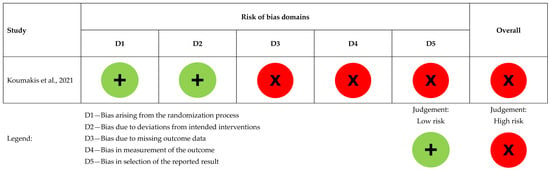

Figure 2. Risk of bias assessment for the randomized controlled study (n = 1), [5].

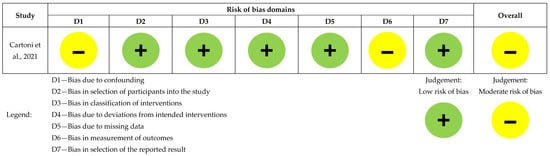

Figure 2. Risk of bias assessment for the randomized controlled study (n = 1), [5]. Figure 3. Risk of bias assessment for the non-randomized comparative study (n = 1), [13].

Figure 3. Risk of bias assessment for the non-randomized comparative study (n = 1), [13]. Table 4. Risk of bias assessment of observational, case report, and qualitative studies (n = 10).

Table 4. Risk of bias assessment of observational, case report, and qualitative studies (n = 10).

All forms were piloted on a subset of studies and refined prior to full extraction. Two reviewers completed the forms independently and reconciled discrepancies by discussion to consensus (see Section 2.5).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

The initial search across the four databases yielded 301 records. After removing duplicates (n = 226) and excluding inaccessible articles (n = 12), 63 articles remained. Following title and abstract screening, 47 articles were excluded. Sixteen full-text articles were then assessed for eligibility, of which four were excluded: three for not reporting relevant outcomes and one for lacking an appropriate intervention. In total, 12 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

In this review, most studies originated from America, specifically from the United States [33,34,35,36,37] and Brazil [3]. One study was multicentric, including participants from both the United States of America and Italy [18]. In Europe, studies were conducted in Denmark [38] and Italy [39]. Two additional multicentric European studies included Austria and Italy [13] and Czechia, Germany, Greece, Italy, and the United Kingdom [5]. Finally, one study was from Asia, namely China [23].

We included six observational studies—four retrospective [3,18,23,34], one prospective [36], and one cross-sectional [35]—as well as two case studies [38,39], one RCT [5], one mixed-methods case study [37], one non-randomized comparative study [13], and one qualitative study [33].

Across the 12 included studies, the overall sample comprised 42,053 participants. This number is strongly influenced by the largest study [34], which reported 41,789 hospitalizations of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Excluding this outlier, the remaining 11 studies included 264 patients, caregivers, or cases.

Populations mainly involved adults with acute myeloid leukemia (n = 5), multiple myeloma (n = 5), myelodysplastic syndromes (n = 5), and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (n = 3). Across studies, patients often had advanced disease stages, poor performance status, or limited prognosis (n = 7).

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

Koumakis et al. had a high overall risk of bias. Randomization was low risk, but due to ongoing MyPal trials, only validation results were available, limiting the assessment of other domains [5], as presented in Figure 2.

Cartoni et al. had low risk across all domains except for confounding and outcome measurement bias [13], as seen in Figure 3.

Risk of bias for nine studies assessed using CASP checklists is summarized in Table 4, with two studies [37,39] assessed for both qualitative and cohort studies.

Chan et al. and Henckel et al. were assessed with low risk across all domains [23,33].

For Weisse et al. the overall quality was moderate due to selection/referral bias, small cohort size, and limited generalizability, with a predominance of women and high median age, potentially limiting applicability to broader populations [37].

Weisse et al. and Bigi et al. were evaluated using qualitative criteria, with all domains marked ‘yes,’ except for the researcher-participant relationship, marked ‘can’t tell‘ due to insufficient detail [37,39].

In the quantitative assessments of Ebert et al. and Bigi et al., confounding factors were not controlled [3,39].

Richter et al. had low risk of bias, except for cohort recruitment, due to selection bias from excluding severely ill individuals [35].

Samala et al. had incomplete follow-up (60%), small cohort size, and demographic limitations, reducing generalizability, resulting in mixed bias ratings [36].

Jackson et al. had follow-up issues, as rehospitalizations could not be tracked due to data limitations [34].

Potenza et al. acknowledged retrospective limitations and single-center design, marking some domains as ‘can’t tell’ for confounding and applicability [18].

The case report by Sørensen et al. [38] had low risk of bias, with all domains marked ‘yes’ (see Table 4).

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

The main results of individual studies for the outcomes included in this review are presented in Table 3.

3.5. Results of Syntheses

3.5.1. Early Palliative Care in Patients with Hematologic Malignancies

Based on our interpretation of the definitions of EPC only five studies were judged to have implemented truly EPC, as shown in Table 2. In three studies, the information provided was insufficient to determine whether the intervention qualified as early. In the remaining studies, there was no clear intervention to classify, or PC was delivered in a hospice context, making it incompatible with typical definitions of EPC.

3.5.2. Quality of Life

Five studies addressed QOL [5,33,35,36,38]; however, only two–both of high methodological quality–specifically evaluated the impact of EPC on QOL [36,38]. In Sørensen et al.’s case study involving a patient with a newly diagnosed Multiple Myeloma (MM), no significant improvement in QOL scores was observed over a 10-week period following the first specialized PC consultation [38]. Conversely, Samala et al. reported a notable improvement in overall QOL after 12 months of EPC involvement in patients with newly diagnosed MM [36].

3.5.3. Symptom Control/Burden

Two studies focused on symptom burden [13,39]. Four studies addressed pain [18,23,36,38], two investigated depression and anxiety [23,36], one assessed appetite [23], and one evaluated multiple domains of well-being [36].

Symptom Burden

Regarding symptom burden, Cartoni et al., in a moderate risk of bias study comparing early home PC with standard hospital care, reported no significant differences between groups [13]. However, these findings should be interpreted cautiously, as patients in the early home PC group were generally older, frailer, and had a poorer prognosis.

Bigi et al., in a community case study of HM patients referred to two EPC units, did not provide a direct comparison between early and late referral groups at the Carpi Unit but observed that patients tended to report improvements in symptom burden regardless of referral timing [39].

Symptom Control

In four studies assessing pain, EPC was associated with improvements in pain scores over time [18,23,36,38]; contributing studies showed low or some concerns for risk of bias.

Chan et al., in a retrospective study of 38 patients with advanced HM, observed a significant improvement in mean symptom scores for depression and anxiety after the fourth follow-up [23]. Conversely, Samala et al. reported no significant changes in depression or anxiety scores over time [36].

Chan et al. also demonstrated a significant improvement in appetite scores after the fourth follow-up [23].

Samala et al. reported improved functional well-being but found no significant changes in physical, social, or emotional well-being subscales [36].

3.5.4. Place of Death

This outcome was addressed in two studies [18,39]; contributing studies had low risk of bias or some concerns.

Bigi et al. evaluated an EPC program across two units. In the Carpi unit, patients were more likely to die at home regardless of the timing of referral to PC. In the Modena unit, similar findings were reported, with 50.7% of patients dying at home or in a hospice and only 5.3% dying in an acute care facility. However, the study did not analyze the relationship between timing of referral and POD in the Modena unit [39].

Potenza et al. reported that patients receiving EPC were more likely to die at home or in hospice rather than in hospital or acute care settings [18].

3.5.5. Healthcare Costs

Only one study addressed this outcome. Bigi et al. concluded that early home PC was less expensive than standard hospital care, resulting in a weekly saving of 2314.90 euros for the healthcare provider. Additionally, it was found to be cost-effective, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of 7013.90 euros per prevented day of care due to avoided infections [39].

3.5.6. Healthcare Utilization

This outcome was assessed in three studies [13,18,39].

One study showed that the mean weekly time per patient dedicated by physicians and nurses was lower in the EPC group compared to standard hospital care [13].

Two studies reported a reduced use of transfusions among patients receiving EPC [13,18].

Two studies found that late PC referrals were associated with greater use of chemotherapy [18,39].

Potenza et al. also reported higher opioid use in patients receiving early supportive/PC. Additionally, these authors found that patients with early supportive/PC had lower HCU, including fewer interventions such as intubation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation, as well as reduced ED visits, ICU admissions, and multiple hospitalizations [18].

Taken together, the findings across studies reveal common patterns despite heterogeneity in design, population, and outcome measures. While individual results are detailed above, the following summary synthesizes the overall direction and consistency of effects across the prespecified outcomes—QOL, SCB, POD, HCU, and HCCs—providing a concise overview of the main signals emerging from the evidence base.

3.6. Summary Across Outcomes

- SCB: EPC improved symptom control in three studies, particularly pain and related domains (numerical improvements over time in pain; gains in energy/appetite reported) [18,23,36].

- QOL: Findings were mixed. One study showed significant QOL improvement at 12 months [36]; another suggested potential QOL gains with a digital e-PRO platform [5]; a case report showed stable QOL [38].

- HCU: EPC was associated with reduced utilization in ≥3 studies—fewer transfusions, less chemotherapy near EOL, and fewer ICU admissions/ED visits/multiple hospitalizations [13,18,39].

- HCCs: Lower costs were reported in one comparative study of early home PC vs. hospital care [13].

- POD: Two studies showed a shift toward home/hospice deaths with earlier referral/integration [18,39].

- Survival: Signals were inconsistent/limited; one program reported higher 1-year survival with EPC compared with delayed referral [39], while other data were descriptive or not EPC-specific.

Axial/theme: EPC was consistently linked with fewer aggressive EOL markers (e.g., less late chemotherapy, ICU, ED/multiple admissions) and greater alignment with preferred care settings (home/hospice), with pain improvement the clearest patient-level benefit; QOL results were heterogeneous across instruments and designs.

Across studies, several outcomes tended to co-occur. Improvements in SCB—particularly pain relief and functional well-being—were frequently accompanied by reduced HCU and a shift in POD toward home or hospice settings [13,18,39]. These patterns suggest that earlier EPC integration may simultaneously influence both patient-centered outcomes and indicators of healthcare intensity, although causal inferences cannot be drawn.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

Across 12 studies, EPC improved SCB (n = 6)—notably pain, appetite, and functional well-being—while results for anxiety and depression were mixed. For QOL (n = 5), findings were mixed. EPC reduced HCU (n = 3)—including fewer transfusions, less late chemotherapy, and fewer aggressive interventions—and lowered HCC in one study (home-based EPC). EPC was associated with a shift in POD toward home or hospice (n = 2). These patterns support timely referral to EPC in HM.

4.2. Early Palliative Care in Patients with Hematologic Malignancies

Only five studies met the criteria for genuine EPC, defined as the integration of PC early in the disease trajectory. There is no consensus on the timing that qualifies a PC intervention as “early,” with definitions varying across studies. In available interventional research, EPC is often defined as an intervention delivered within 8 to 12 weeks of diagnosis. For example, Vergnenègre et al. considered EPC to be initiated within three months of diagnosis in their prospective observational study [40], consistent with Hui et al. who adopted a similar timeframe in their retrospective cohort analysis [9]. In contrast, other studies aligned with the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines, which defined EPC as an intervention occurring within 8 weeks of diagnosis [41,42].

Recent updates to the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines have shifted away from strict time-based definitions [43]. Instead, they recommend referring patients with advanced cancer to specialized, interdisciplinary PC teams early in the course of the disease, alongside active cancer treatment. The guidelines emphasize that “early” should not be interpreted as waiting until cessation of antineoplastic therapy, but rather as responding to the presence of palliative needs [43].

EPC has also been defined by other parameters, including the setting of the intervention, such as outpatient versus inpatient consultation [44], or by the duration of continuity of care before death (e.g., >90 days, 31–90 days, 11–30 days, and 1–10 days) [45].

In a recent scoping review that investigated how EPC was defined in the literature for adults with life-limiting illnesses, definitions for EPC were organized in five categories: time-based, prognosis-based, location-based, treatment-based and symptom-based [46]. Among patients with cancer, most EPC definitions described were time-based and the majority of studies considered EPC when the patients were diagnosed with advanced cancer within the previous 6–8 weeks. Differently, in multiple or non-cancer diagnosis the most common definition category was symptom-based [46].

These variations underscore the absence of a universally accepted definition of EPC and the complexity of operationalizing it in research and clinical practice.

While a growing body of literature demonstrates the many benefits of EPC in adults with advanced cancer, evidence supporting its role in HM remains limited and warrants further investigation. There are barriers to equitable access to PC, including difficulties in identifying patients nearing the EOL, the “survival imperative,” the “normalization of dying,” misconceptions, mistrust, limited information about PC and EOL care, and a fragmented care system [47].

Although the integration of PC into cancer care represents a patient- and family-centered, interdisciplinary approach recommended throughout the disease trajectory, its early implementation remains limited; delays in referral–often reducing PC to EOL interventions–may reflect a persistent lack of knowledge, training, and preparedness among healthcare professionals to address serious illness and the dying process, raising ethical concerns about the preservation of human dignity [48].

Several studies have identified potential causes for delayed PC referral in this population [2,10,49,50,51,52,53,54]. One study categorized these barriers into three broad domains: cultural, illness-specific, and system-based [2]. Cultural barriers include misconceptions equating PC solely with EOL care and a general lack of awareness about its broader benefits throughout the disease trajectory. Illness-specific barriers stem from the unpredictable and complex nature of HM, the aggressive and prolonged treatments involved, and prognostic uncertainty, all of which complicate the timing of PC integration. System-based barriers often include limited availability of EOL care services and constraints in delivering blood products in hospice settings [2].

Late referrals, when patients are already significantly ill, limit the time available for PC teams to establish a therapeutic relationship and implement effective interventions. These delays may reduce the overall impact and benefits of PC in this population. To address these barriers and enhance the integration of PC, several strategies have been proposed.

One effective approach involves rebranding PC as “supportive care”, a change shown to reduce stigma and substantially increase early referrals. In one study, early PC referrals rose from 43% to 81% among solid tumor specialists and from 21% to 66% among hematologic specialists following this terminology shift [55]. Salins et al. similarly emphasized the importance of renaming PC as “supportive care” as a key recommendation from oncologists [56]. Other enablers of equitable and timely referral to PC include thorough patient evaluation, addressing basic survival needs and social determinants of access, and fostering intersectoral collaboration, community advocacy, and engagement [47].

Beyond terminology, improving awareness and fostering positive attitudes toward PC are essential to promote timely referrals [52]. This may be achieved by incorporating PC training into hematology and oncology residency programs and ensuring that PC providers possess cancer-specific knowledge and skills [56]. These steps are crucial to strengthening the integration of PC into standard cancer practice.

4.3. Early Palliative Care and Quality of Life

In our systematic review, Samala et al. reported that in patients with newly diagnosed MM, EPC involvement over 12 months led to an improvement in overall QOL [36]. In contrast, the case report by Sørensen et al. did not show any changes in QOL scores following EPC intervention [38]. The inconsistency in QOL findings may be explained by the use of different assessment instruments across studies, each measuring distinct domains and applying non-equivalent scoring systems.

The literature on the impact of EPC on QOL in patients with HM remains scarce. However, several studies in other patient populations have demonstrated benefits. Temel et al., in an RCT involving patients with metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), showed that early PC integration significantly improved QOL, reduced depressive symptoms, led to less aggressive EOL care, and even prolonged survival [57]. Similar findings were observed in another RCT by Chen et al. also involving NSCLC patients, where EPC was associated with extended survival, improved QOL, greater psychological stability, reduced pain, and better nutritional satisfaction [58]. Additional studies have also supported the positive impact of EPC in patients with advanced cancer across a range of outcomes [59,60,61,62,63]. Nonetheless, the evidence is not unanimous, either for cancer or non-cancer patients. For instance, Allende et al., in an RCT conducted in Mexico, found no significant differences in QOL or symptom burden between EPC and standard oncological care in patients with metastatic NSCLC [64]. Similarly, a recent review reported no significant QOL differences between EPC and usual care in patients with heart failure, end-stage liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [20].

4.4. Early Palliative Care and Symptom Control/Burden

The literature consistently shows that patients with HM experience a high symptom burden [26,65], stemming not only from the disease itself but also from the aggressive treatments often administered near the EOL [7,8,9]. Consequently, these patients are clear candidates for PC, which can improve QOL through a multidisciplinary approach that addresses physical, spiritual, and psychosocial needs. Given these benefits, PC should be considered a standard component of care for this population. However, several studies indicate that patients with HM are less likely to receive PC or hospice care compared to patients with solid tumors [4,8,53]. Moreover, when PC referrals do occur, they are frequently delayed, often taking place in the final days of life [26,66].

This issue was evident in one of the studies included in our systematic review, conducted by Ebert et al., which reported that patients with HM, particularly those with MM and acute leukemia, presented with significant symptom burden at the time of their first PC consultation [3]. Notably, the study revealed limited and delayed access to PC services, especially for patients with acute leukemia; only 18 of 97 patients with this diagnosis were referred to PC during the study period [3].

Due to such delays, the evidence on the impact of EPC on symptom burden in HM remains limited. In our review, six studies assessed SCB, with improvements reported in pain [18,23,36,38], depression and/or anxiety [23], and appetite [23]. However, in the prospective cohort study by Samala et al., depression and anxiety scores did not significantly change over time [36].

A recent study comparing EPC to usual hematologic care in patients newly diagnosed with MM supports the integration of EPC into standard care. It demonstrated that pain intensity significantly decreased over time in the EPC group, but not in the control group [67].

Haun et al., in a systematic review, concluded that EPC may improve QOL and symptom intensity in patients with advanced cancer compared to standard care. Although effect sizes were small, they may still be clinically meaningful in late-stage disease. However, levels of depressive symptoms did not differ significantly between patients receiving EPC and those receiving usual care [68].

Additional studies involving patients with advanced cancer have also demonstrated the positive effects of EPC on symptom burden [59,61,62]. Nonetheless, some studies [59,61,62] found no significant differences, specifically in anxiety [59,61] or depression [61].

To conclude this part of the discussion, it is important to recall the evidence concerning patients with advanced non-cancer diseases who also often experience late referral to PC due to prognostic uncertainty. A 2025 systematic review on EPC in non-oncological populations found that EPC reduced anxiety and depression in stroke patients and improved pain interference and fatigue in those with heart failure. However, findings on anxiety and depression in heart failure patients were inconsistent [20].

4.5. Early Palliative Care and Place of Death

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Howell et al. revealed that patients with HM are more than twice as likely to die in hospital compared to those with other types of cancer, despite home being widely recognized as the preferred setting for EOL care [4].

While limited evidence directly links EPC to POD in HM populations, findings from other serious illnesses suggest a positive impact. For example, a single-center retrospective observational study by Rodrigo-Troyano et al., involving patients with interstitial lung diseases, demonstrated that EPC referral was independently associated with a reduced risk of hospital admissions during the last year of life and a lower likelihood of dying in hospital [11]. Similarly, Bassi et al. reported that initiating an EPC program at the time of diagnosis significantly reduced hospital death rates, instead increasing the likelihood of dying at home or in hospice settings [12].

4.6. Early Palliative Care and Healthcare Costs

HCCs were addressed in one study included in this review, which suggested that early home PC for patients with HM was less expensive than standard hospital care [13]. Supporting this, a prospective cohort study conducted at a large academic medical center found that patients who received early inpatient PC consultations had a significantly greater reduction in total HCC compared to those who received later referrals [14]. Specifically, EPC patients saw an average, and statistically significant, decline of $1431 in total costs in the 1-day pre/post consultation period, compared to a $403 reduction in the late PC cohort. Over a 3-day period, the total cost reduction was $5839 for the EPC group versus $1478 for the late PC group (p < 0.001) [14].

In other serious illnesses, similar trends were observed. For instance, in end-stage liver disease, a retrospective review found that hospitalization costs were significantly lower among those referred early to PC referrals [15].

Conversely, a retrospective study involving both cancer and non-cancer patients found that earlier involvement of specialist PC was associated with higher overall HCC during the last year of life. However, in the final 1 and 3 months of life costs were lower in the PC group, largely due to reduced hospitalizations [16]. This trend was also confirmed by Seow et al., who reported decreased healthcare expenditures in the last month of life among cancer patients receiving PC, again primarily attributed to fewer hospital admissions [17].

4.7. Early Palliative Care and Healthcare Utilization

This outcome was assessed in three studies. Overall, the findings indicated that EPC was associated with reduced HCU. This was reflected in shorter time spent per patient [13], lower rates of blood transfusions [13,18], chemotherapy [13,18], intubation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, fewer ICU admissions, multiple hospitalizations, and fewer ED visits [18]. Only one study reported a higher use of opioids among patients receiving early supportive/PC [18], which is not surprising given that opioids are essential for effective symptom management in PC settings.

The broader literature on HCU shows similar trends. For example, in patients with end-stage liver disease, EPC referral was associated with significantly fewer endoscopies and blood transfusions [15]. In interstitial lung diseases, EPC was independently associated with a lower risk of hospital admissions in the last year of life [11]. Bevins et al. also reported fewer ED visits and reduced ICU admissions in patients with pancreatic cancer who received EPC [19]. A recent review showed that EPC positively influenced time to first readmission and increased days alive outside the hospital among patients with end-stage liver disease [20].

However, not all studies confirm these findings. In an RCT involving patients with advanced cancer, Bakitas et al. found no significant differences between early and delayed PC groups in terms of HCU. This included hospital days, ICU days, ED visits, chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life, and rates of home death [69]. Similarly, Vanbutsele et al., in another RCTs did not observe significant differences in HCU between the intervention and control groups [63].

4.8. Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review has several strengths. It is one of the few reviews that specifically examines the impact of EPC in patients with HM, addressing an important but underexplored area in palliative hematology/oncology. A rigorous search strategy was applied across multiple databases, and the review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines, including a critical appraisal of the identified studies.

The review evaluates a wide range of outcomes, including QOL, SCB, HCU, HCCs, and POD, thereby providing a comprehensive overview of EPC’s potential benefits in this population. It includes findings from diverse study designs—such as RCTs, cohort studies, and case studies—conducted across different healthcare systems, which enhances the breadth and depth of interpretation. Beyond clinical outcomes, it also critically explores cultural, disease-specific, and system-level barriers to EPC integration, offering valuable practical insights for implementation. Furthermore, this review contributes to raising awareness of an underexplored area in HM, a field traditionally characterized by late PC referrals and aggressive EOL treatments. By synthesizing the benefits and challenges of EPC, it underscores the urgent need for further research and for integrating EPC into standard hematologic care.

Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. This review received no funding, which restricted access to some paid articles and may have reduced the comprehensiveness of the evidence base. The number of studies addressing EPC in HM remains limited, and much of the higher-quality evidence derives from populations with solid tumors, reducing generalizability to HM. The included studies were heterogeneous in design, sample size, disease subtypes, timing and structure of EPC interventions, and outcome measures, precluding meta-analysis and limiting comparability. Many were observational, introducing risks of bias such as selection bias and non-standardized treatment protocols, while the lack of RCT restricts the ability to draw firm causal inferences.

Additional methodological constraints should also be considered. Language and access restrictions may have introduced selection and publication bias. We limited inclusion to English-language publications and excluded studies whose full texts were inaccessible via our institutional library; we did not request interlibrary loans or contact authors. These constraints may bias the evidence toward settings and journals with greater English-language indexing and subscription availability and may underrepresent studies from low- and middle-income countries or non-English contexts. Accordingly, estimates of effect and generalizability should be interpreted with caution. Moreover, if the search was limited to specific databases, important studies may have been inadvertently omitted. PROSPERO registration occurred after screening had started—although before data extraction and synthesis—which is suboptimal for transparency; however, no post hoc changes were made to objectives, eligibility, outcomes, or the synthesis plan. Citation tracking and reference list screening were not performed, and no formal evidence grading framework was applied, which reduces both the interpretability and the clinical applicability of the findings. Finally, there is still no consensus on standardized definitions or models of what constitutes “early” PC, complicating the assessment of its true impact.

4.9. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Future Research

Practice. In adults with HM, EPC appears to improve SCB—particularly pain and functional well-being—based on multiple contributing studies (see Results: SCB). Findings for QOL were mixed (Results: QOL). EPC was associated with a shift in POD toward home/hospice in limited studies (Results: POD) and with lower HCU (e.g., fewer transfusions, less late chemotherapy, fewer ICU/ED/hospital admissions) in several studies (Results: HCU), with cost-saving signals in one comparative analysis (Results: HCCs). Clinicians should consider timely referral to EPC when symptom load escalates or at diagnosis of advanced disease, coordinated closely with hematology to align goals of care and symptom management (Results: Summary across outcomes).

Policy. Health systems should facilitate timely access to EPC in hematology by resourcing integrated/embedded models and by tracking patient-centered outcomes (SCB, QOL) alongside care-intensity metrics (POD, HCU, HCCs) reflected in our review (Results: POD/HCU/HCCs). Given mixed QOL findings and heterogeneous tools, policies should also promote standardized outcome measurement across services (Results: QOL).

Future Research. Priorities include the following: (i) prospective comparative designs/RCT where feasible to strengthen causal inference; (ii) evaluations of optimal timing and models (embedded, home-based, e-PRO-enabled); (iii) robust economic analyses (HCCs) and linkage with HCU/POD; and (iv) harmonized, validated QOL/SCB instruments to reduce measurement heterogeneity that may obscure effects (Results: QOL). Multicenter studies in diverse settings are needed to improve generalizability.

5. Conclusions

Building on prior evidence for specialty PC in HM [26], this EPC-focused update (2020–2024) suggests that earlier integration appears to improve SCB—particularly pain—and may reduce aggressive EOL indicators, HCU, and HCCs, with a shift in POD toward home/hospice in limited studies. Findings for QOL and psychological outcomes were mixed, likely influenced by heterogeneous instruments. Late PC referral remains common and likely attenuates potential benefits. Future rigorously designed studies should clarify causal effects and identify which EPC components (including embedded/home-based and ePRO-enabled models) yield the greatest benefit in HM.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13212789/s1, Table S1: Database search strategies.

Author Contributions

This study was conceptualized by P.F.-A. and P.R.-P. P.F.-A. and P.R.-P. conducted searches and screening of articles, analyzed data, designed the review protocol, wrote the manuscript, reviewed it, and approved the definitive version of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article, from public, commercial or non-profit funding agencies.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, Large language model, OpenAI, 2025, https://chat.openai.com/) for the purposes of Graphical Abstract. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest regarding the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

CASP—Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; ED—Emergency Department; EOL—End-of-Life; EPC—Early Palliative Care; e-PRO—electronic Patient-Reported Outcomes; HCC—Healthcare Cost; HCU—Healthcare Utilization; HM—Hematologic Malignancy; ICU—Intensive Care Unit(s); MM—Multiple Myeloma; NSCLC—Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer; PC—Palliative Care; POD—Place of Death; QOL—Quality of Life; RCT—Randomized Controlled Trial(s); SCB—Symptom Control/Burden.

References

- Tietsche de Moraes Hungria, V.; Chiattone, C.; Pavlovsky, M.; Abenoza, L.M.; Agreda, G.P.; Armenta, J.; Arrais, C.; Avendaño Flores, O.; Barroso, F.; Basquiera, A.L.; et al. Epidemiology of Hematologic Malignancies in Real-World Settings: Findings from the Hemato-Oncology Latin America Observational Registry Study. J. Glob. Oncol. 2019, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jawahri, A.; Nelson, A.M.; Gray, T.F.; Lee, S.J.; LeBlanc, T.W. Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Patients With Hematologic Malignancies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, R.P.C.; Magnus, M.M.; Toro, P.; Manoel, F.G.; Costa, F.F.; Olalla Saad, S.T.; de Melo Campos, P. Hematologic Malignancies Patients Face High Symptom Burden and Are Lately Referred to Palliative Consultation: Analysis of a Single Center Experience. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2023, 40, 761–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, D.A.; Shellens, R.; Roman, E.; Garry, A.C.; Patmore, R.; Howard, M.R. Haematological malignancy: Are patients appropriately referred for specialist palliative and hospice care? A systematic review and meta-analysis of published data. Palliat. Med. 2011, 25, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koumakis, L.; Schera, F.; Parker, H.; Bonotis, P.; Chatzimina, M.; Argyropaidas, P.; Zacharioudakis, G.; Schäfer, M.; Kakalou, C.; Karamanidou, C.; et al. Fostering Palliative Care Through Digital Intervention: A Platform for Adult Patients with Hematologic Malignancies. Front. Digit. Health 2021, 3, 730722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, T.W.; El-Jawahri, A. When and why should patients with hematologic malignancies see a palliative care specialist? Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2015, 2015, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasch, B.; Kalies, H.; Feddersen, B.; Ruderer, C.; Hiddemann, W.; Bausewein, C. Care of cancer patients at the end of life in a German university hospital: A retrospective observational study from 2014. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Didwaniya, N.; Vidal, M.; Shin, S.H.; Chisholm, G.; Roquemore, J.; Bruera, E. Quality of end-of-life care in patients with hematologic malignancies: A retrospective cohort study. Cancer 2014, 120, 1572–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Kim, S.H.; Roquemore, J.; Dev, R. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer 2014, 120, 1743–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, T.W.; Roeland, E.J.; El-Jawahri, A. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Hematologic Malignancies: Is It Really so Difficult to Achieve? Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2017, 12, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Troyano, A.; Alonso, A.; Barril, S.; Fariñas, O.; Güell, E.; Pascual, A.; Castillo, D. Impact of Early Referral to Palliative Care in Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease. J. Palliat. Med. 2022, 25, 1422–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassi, I.; Pastorello, S.; Guerrieri, A.; Giancotti, G.; Cuomo, A.M.; Rizzelli, C.; Coppola, M.; Valenti, D.; Nava, S. Early palliative care program in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients favors at-home and hospice deaths, reduces unplanned medical visits, and prolongs survival: A pilot study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 128, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartoni, C.; Breccia, M.; Giesinger, J.M.; Baldacci, E.; Carmosino, I.; Annechini, G.; Palumbo, G.; Armiento, D.; Niscola, P.; Tendas, A.; et al. Early Palliative Home Care versus Hospital Care for Patients with Hematologic Malignancies: A Cost-Effectiveness Study. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.J.; Akhtar, S.; Huppertz, J.W.; Sidhu, M.; Coates, A.; Knudsen, N. Prospective Cohort Study on the Impact of Early Versus Late Inpatient Palliative Care on Length of Stay and Cost of Care. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2023, 40, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.; Woodman, R.J.; Kleinig, P.; Briffa, M.; To, T.; Wigg, A.J. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic: Early palliative care referral in patients with end-stage liver disease is associated with reduced resource utilization. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 35, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, P.; Liu, D.; Fiebig, D.; Hall, J.; Millican, J.; Aranda, S.; van Gool, K.; Haywood, P. Specialist Palliative Care and Health Care Costs at the End of Life. PharmacoEconomics Open 2024, 8, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, H.; Barbera, L.C.; McGrail, K.; Burge, F.; Guthrie, D.M.; Lawson, B.; Chan, K.K.W.; Peacock, S.J.; Sutradhar, R. Effect of Early Palliative Care on End-of-Life Health Care Costs: A Population-Based, Propensity Score–Matched Cohort Study. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2022, 18, e183–e192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potenza, L.; Scaravaglio, M.; Fortuna, D.; Giusti, D.; Colaci, E.; Pioli, V.; Morselli, M.; Forghieri, F.; Bettelli, F.; Messerotti, A.; et al. Early palliative/supportive care in acute myeloid leukaemia allows low aggression end-of-life interventions: Observational outpatient study. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, 14, e1111–e1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevins, J.; Bhulani, N.; Goksu, S.Y.; Sanford, N.N.; Gao, A.; Ahn, C.; Paulk, M.E.; Terauchi, S.; Pruitt, S.L.; Tavakkoli, A.; et al. Early Palliative Care Is Associated with Reduced Emergency Department Utilization in Pancreatic Cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 44, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mós, J.R.; Reis-Pina, P. Early Integration of Palliative Care in Nononcological Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2025, 69, e283–e302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Alonso, D.; Porta-Sales, J.; Monforte-Royo, C.; Trelis-Navarro, J.; Sureda-Balarí, A.; Fernández De Sevilla-Ribosa, A. Palliative care in patients with haematological neoplasms: An integrative systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, T.W.; O’Donnell, J.D.; Crowley-Matoka, M.; Rabow, M.W.; Smith, C.B.; White, D.B.; Tiver, G.A.; Arnold, R.M.; Schenker, Y. Perceptions of Palliative Care Among Hematologic Malignancy Specialists: A Mixed-Methods Study. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015, 11, e230–e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.Y.; Gill, H.; Chan, T.S.Y.; Li, C.W.; Tsang, K.W.; Au, H.Y.; Wong, C.Y.; Hui, C.H. Early integrated palliative care for haematology cancer patients—The impact on symptom burden in Hong Kong. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 6316–6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Welch, V.A.; Flemyng, E. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5; Cochrane: London, UK, 2024; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, E.; Watson, T.; Singh, D.; Wong, C.; Lo, S.S. Outcomes of Specialty Palliative Care Interventions for Patients with Hematologic Malignancies: A Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br. Med. J. 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.; Higgins, J. ROBINS-I V2: Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies—Of Interventions, Version 2. 2024. Available online: https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/robins-i-v2 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- CASP—Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklist: CASP Cohort Study Checklist. 2020. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/cohort-study-checklist/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- CASP—Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklist: CASP Cross-Sectional Studies Checklist. 2020. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/cross-sectional-studies-checklist/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- CASP—Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklist: CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. 2020. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/qualitative-studies-checklist/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports. 2020. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Henckel, C.; Revette, A.; Huntington, S.F.; Tulsky, J.A.; Abel, G.A.; Odejide, O.O. Perspectives Regarding Hospice Services and Transfusion Access: Focus Groups with Blood Cancer Patients and Bereaved Caregivers. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 59, 1195–1203.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, I.; Etuk, A.; Jackson, N. Prevalence and Predictors of Palliative Care Utilization among Hospitalized Patients with Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J. Palliat. Care 2023, 38, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J.; Sanchez, L.; Biran, N.; Wang, C.K.; Tanenbaum, K.; DeVincenzo, V.; Grunman, B.; Vesole, D.H.; Siegel, D.S.; Pecora, A.; et al. Prevalence and Survival Impact of Self-Reported Symptom and Psychological Distress Among Patients with Multiple Myeloma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021, 21, e284–e289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samala, R.V.; Nurse, D.P.; Chen, X.; Wei, W.; Crook, J.J.; Fada, S.D.; Valent, J. Effects of early palliative care integration on patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisse, C.S.; Melekis, K.; Cheng, A.; Konda, A.K.; Major, A. Mixed-Methods Study of End-of-Life Experiences of Patients with Hematologic Malignancies in Social Hospice Residential Home Care Settings. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2024, 20, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, J.; Sørensen, T.V.; Andersen, K.H.; Nørøxe, A.D.S.; Mylin, A.K. Early, Patient-Centered, and Multidisciplinary Approach in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: What Are We Talking About? A Case Description and Discussion. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2022, 3, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigi, S.; Borelli, E.; Potenza, L.; Gilioli, F.; Artioli, F.; Porzio, G.; Luppi, M.; Bandieri, E. Early palliative care for solid and blood cancer patients and caregivers: Quantitative and qualitative results of a long-term experience as a case of value-based medicine. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1092145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergnenègre, A.; Hominal, S.; Tchalla, A.E.; Bérard, H.; Monnet, I.; Fraboulet, G.; Baize, N.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Robinet, G.; Oliviero, G.; et al. Assessment of palliative care for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in France: A prospective observational multicenter study (GFPC 0804 study). Lung Cancer 2013, 82, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nottelmann, L.; Groenvold, M.; Vejlgaard, T.B.; Petersen, M.A.; Jensen, L.H. Early, integrated palliative rehabilitation improves quality of life of patients with newly diagnosed advanced cancer: The Pal-Rehab randomized controlled trial. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S.; Sloan, J.; Zemla, T.; Greer, J.A.; Jackson, V.A.; El-Jawahri, A.; Kamdar, M.; Kamal, A.; Blinderman, C.D.; Strand, J.; et al. Multisite, Randomized Trial of Early Integrated Palliative and Oncology Care in Patients with Advanced Lung and Gastrointestinal Cancer: Alliance A221303. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.J.; Temin, S.; Ghoshal, A.; Alesi, E.R.; Ali, Z.V.; Chauhan, C.; Cleary, J.F.; Epstein, A.S.; Firn, J.I.; Jones, J.A.; et al. Palliative Care for Patients with Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2336–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantilat, S.Z.; O’Riordan, D.L.; Dibble, S.L.; Landefeld, C.S. Hospital-based palliative medicine consultation: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 2038–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, G.; Venohr, I.; Conner, D.; McGrady, K.; Beane, J.; Richardson, R.H.; Williams, M.P.; Liberson, M.; Blum, M.; Della Penna, R. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: A randomized control trial. J. Palliat. Med. 2008, 11, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircher, C.E.; Hanna, T.P.; Tranmer, J.; Goldie, C.E.; Ross-White, A.; Moulton, E.; Flegal, J.; Goldie, C.L. Defining “early palliative care” for adults diagnosed with a life-limiting illness: A scoping review. BMC Palliat. Care 2025, 24, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sítima, G.; Galhardo-Branco, C.; Reis-Pina, P. Equity of access to palliative care: A scoping review. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis-Pina, P.; Santos, R.G. Early Referral to Palliative Care: The Rationing of Timely Health Care for Cancer Patients. Acta Medica Port. 2019, 32, 475–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jawahri, A.; Webb, J.A.; Hannon, B.; Zimmermann, C. Integrating Palliative Care and Hematologic Malignancies: Bridging the Gaps for Our Patients and Their Caregivers. ASCO Educ. Book 2024, 44, e432196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franjul Sánchez, A.; Fuentes Armesto, A.M.; Briones Chávez, C.; Ruiz, M. Revisiting Early Palliative Care for Patients with Hematologic Malignancies and Bone Marrow Transplant: Why the Delay? Cureus 2020, 12, e10504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickolich, M.; El-Jawahri, A.; LeBlanc, T.W. Palliative and End-of-Life Care in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2016, 11, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, J.M.; Ellis, E.M.; Reblin, M.; Ellington, L.; Ferrer, R.A. Knowledge of and beliefs about palliative care in a nationally-representative U.S. sample. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanbutsele, G.; Deliens, L.; Cocquyt, V.; Cohen, J.; Pardon, K.; Chambaere, K. Use and timing of referral to specialized palliative care services for people with cancer: A mortality follow-back study among treating physicians in Belgium. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedding, U. Palliative care of patients with haematological malignancies: Strategies to overcome difficulties via integrated care. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e746–e753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Park, M.; Liu, D.; Reddy, A.; Dalal, S.; Bruera, E. Attitudes and Beliefs Toward Supportive and Palliative Care Referral Among Hematologic and Solid Tumor Oncology Specialists. Oncologist 2015, 20, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salins, N.; Ghoshal, A.; Hughes, S.; Preston, N. How views of oncologists and haematologists impacts palliative care referral: A systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yu, H.; Yang, L.; Yang, H.; Cao, H.; Lei, L.; Ma, L.; Liu, S.; Tian, L.; Wang, S. Combined early palliative care for non-small-cell lung cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial in Chongqing, China. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1184961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Fang, P.; Bai, J.; Tan, L.; Wan, C.; Yu, L. Meta-Analysis of Effects of Early Palliative Care on Health-Related Outcomes Among Advanced Cancer Patients. Nurs. Res. 2023, 72, E180–E190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haroen, H.; Maulana, S.; Harun, H.; Mirwanti, R.; Sari, C.W.M.; Platini, H.; Arovah, N.I.; Padila, P.; Amirah, S.; Pardosi, J.F. The benefits of early palliative care on psychological well-being, functional status, and health-related quality of life among cancer patients and their caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Palliat. Care 2025, 24, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.A.; Lelond, S.; Daeninck, P.J.; Rabbani, R.; Lix, L.; McClement, S.; Chochinov, H.M.; Goldenberg, B.A. The impact of early palliative care on the quality of life of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: The IMPERATIVE case-crossover study. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.-H.; Chang, H.-J.; Huang, T.-W. Effects of Early Palliative Care in Advanced Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2022, 39, 1350–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanbutsele, G.; Van Belle, S.; Surmont, V.; De Laat, M.; Colman, R.; Eecloo, K.; Naert, E.; De Man, M.; Geboes, K.; Deliens, L.; et al. The effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in oncology on quality of life and health care use near the end of life: A randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 124, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allende, S.; Turcott, J.G.; Verástegui, E.; Rodríguez-Mayoral, O.; Flores-Estrada, D.; Pérez Camargo, D.A.; Ramos-Ramírez, M.; Martínez-Hernández, J.-N.; Oñate-Ocaña, L.F.; Pina, P.S.; et al. Early Incorporation to Palliative Care (EPC) in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The PACO Randomized Clinical Trial. Oncologist 2024, 29, e1373–e1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, A.S.; Goldberg, G.R.; Meier, D.E. Palliative care and hematologic oncology: The promise of collaboration. Blood Rev. 2012, 26, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allende-Pérez, S.; García-Salamanca, M.F.; Peña-Nieves, A.; Ramírez-Ibarguen, A.; Verástegui-Avilés, E.; Hernández-Lugo, I.; LeBlanc, T.W. Palliative Care in Patients with Hematological Malignancies. We Have a Long Way to Go…. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2023, 40, 1324–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, D.; Colaci, E.; Pioli, V.; Banchelli, F.; Maccaferri, M.; Leonardi, G.; Marasca, R.; Morselli, M.; Forghieri, F.; Bettelli, F.; et al. Early palliative care versus usual haematological care in multiple myeloma: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, 14, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haun, M.W.; Estel, S.; Rücker, G.; Friederich, H.-C.; Villalobos, M.; Thomas, M.; Hartmann, M. with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD011129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakitas, M.A.; Tosteson, T.D.; Li, Z.; Lyons, K.D.; Hull, J.G.; Li, Z.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Frost, J.; Dragnev, K.H.; Hegel, M.T.; et al. Early Versus Delayed Initiation of Concurrent Palliative Oncology Care: Patient Outcomes in the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).