The Role of Self-as-Context as a Self-Based Process of Change in Cancer-Related Pain: Insights from a Network Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Study Criteria

2.3. Recruitment and Study Procedures

2.4. Scales

2.4.1. Conventional Coping Strategies

2.4.2. Self-Based Coping Strategies

2.5. Power Analysis

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample, Descriptive Characteristics, and Preliminary Checking

3.2. Correlation Analyses

3.3. Multivariate Analyses

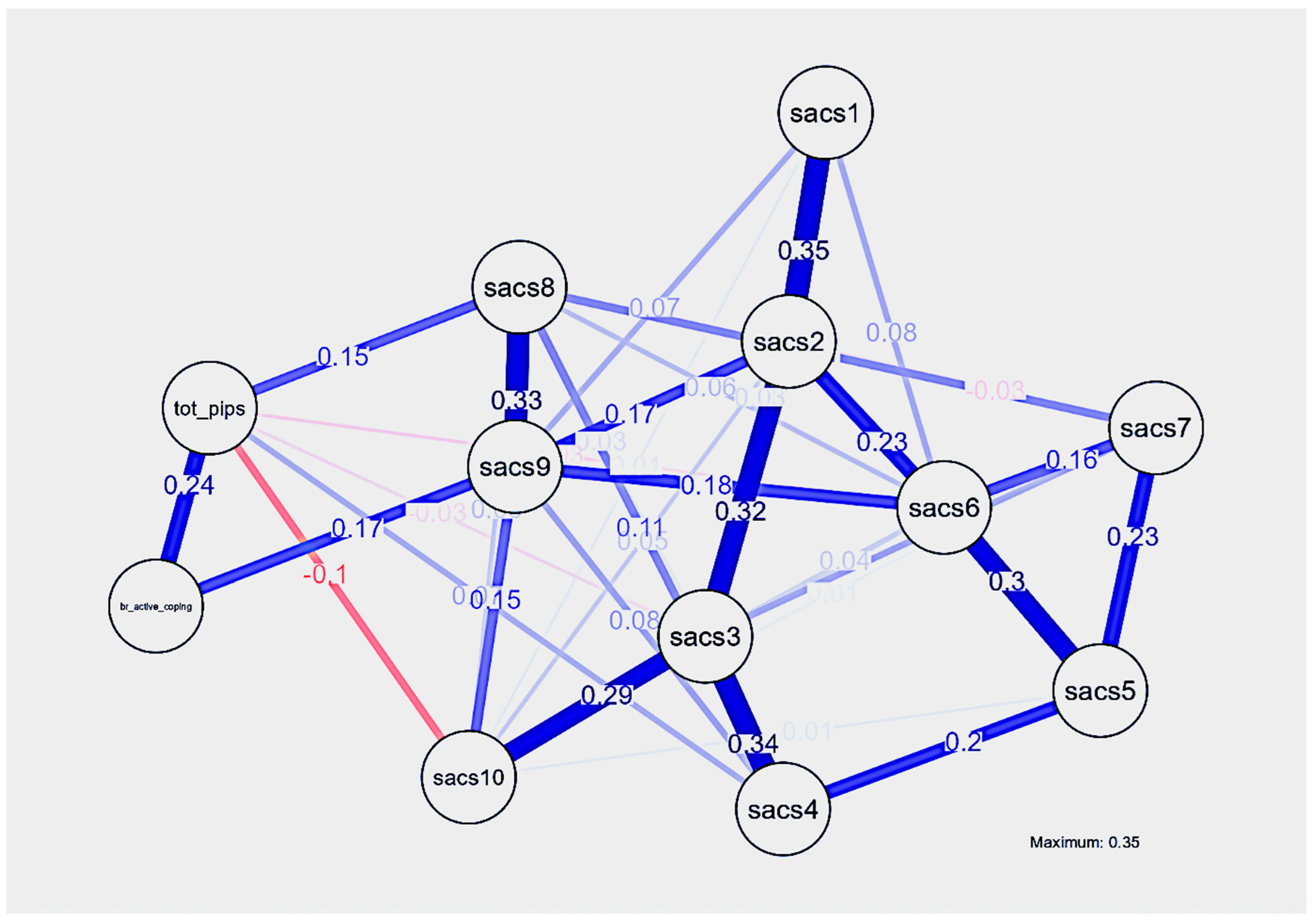

3.4. Resultant Network Analysis

3.4.1. Results of Centrality Indices

3.4.2. Network Accuracy and Stability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yadav, A.K.; Desai, N.S. Cancer stem cells: Acquisition, characteristics, therapeutic implications, targeting strategies and future prospects. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2019, 15, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.I.; Kaasa, S.; Barke, A.; Korwisi, B.; Rief, W.; Treede, R.D. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic cancer-related pain. Pain 2019, 160, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.E. Cancer-related fatigue--mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 11, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galloway, S.K.; Baker, M.; Giglio, P.; Chin, S.; Madan, A.; Malcolm, R.; Serber, E.R.; Wedin, S.; Balliet, W.; Borckardt, J. Depression and Anxiety Symptoms Relate to Distinct Components of Pain Experience among Patients with Breast Cancer. Pain Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 851276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, E.A.; Pedreira, P.B.; Moreno, P.I.; Popok, P.J.; Fox, R.S.; Yanez, B.; Antoni, M.H.; Penedo, F.J. Pain, cancer-related distress, and physical and functional well-being among men with advanced prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 2022, 31, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWit, R.; van Dam, F.; Abu-Saad, H.H.; Loonstra, S.; Zandbelt, L.; van Buuren, A.; van der Heijden, K.; Leenhouts, G. Empirical comparison of commonly used scales to evaluate pain treatment in cancer patients with chronic pain. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 17, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvillemo, P.; Bränström, R. Coping with breast cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner-Sack, A.M.; Menna, R.; Setchell, S.R.; Maan, C.; Cataudella, D. Posttraumatic growth, coping strategies, and psychological distress in adolescent survivors of cancer. J. Pediatr. Hematol./Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 29, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karekla, M.; Panayiotou, G. Coping and experiential avoidance: Unique or overlapping constructs? J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2011, 42, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipp, R.D.; Greer, J.A.; El-Jawahri, A.; Moran, S.M.; Traeger, L.; Jacobs, J.M.; Jacobsen, J.C.; Gallagher, E.R.; Park, E.R.; Ryan, D.P.; et al. Coping and Prognostic Awareness in Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2551–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.L.; Spencer, R.J.; Rausch, M.M. The use of humor in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer: A phenomenological study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2013, 23, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebrack, B.; Isaacson, S. Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaveirdyzadeh, R.; Rahimi, R.; Rahmani, A.; Ghahramanian, A.; Kodayari, N.; Eivazi, J. Spiritual/Religious Coping Strategies and their Relationship with Illness Adjustment among Iranian Breast Cancer Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 17, 4095–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, E.M.; Schüz, N.; Sanderson, K.; Scott, J.L.; Schüz, B. Illness representations, coping, and illness outcomes in people with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 724–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruano, A.; García-Torres, F.; Gálvez-Lara, M.; Moriana, J.A. Psychological and Non-Pharmacologic Treatments for Pain in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 63, e505–e520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, J.; Shao, T.; Huang, H.H.; Kessler, A.J.; Kolodka, O.P.; Shapiro, C.L. Optimism and coping: Do they influence health outcomes in women with breast cancer? A systemic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 183, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, A.; Lucidi, F.; Merluzzi, T.; Alivernini, F.; Laurentiis, M.; Botti, G.; Giordano, A. A meta-analytic review of the relationship of cancer coping self-efficacy with distress and quality of life. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 36800–36811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warth, M.; Zöller, J.; Köhler, F.; Aguilar-Raab, C.; Kessler, J.; Ditzen, B. Psychosocial Interventions for Pain Management in Advanced Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 22, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meints, S.M.; Edwards, R.R. Evaluating psychosocial contributions to chronic pain outcomes. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 87 Pt B, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchman, D.Z.; Ho, A.; Goldberg, D.S. Investigating Trust, Expertise, and Epistemic Injustice in Chronic Pain. J. Bioethical Inq. 2017, 14, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toye, F.; Seers, K.; Allcock, N.; Briggs, M.; Carr, E.; Andrews, J.; Barker, K. A meta- ethnography of patients’ experience of chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2013, 21, S259–S260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, W. The Principles of Psychology; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981; Originally published in 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes, Y.; Hayes, S.C.; Barnes-Holmes, D.; Roche, B. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 2001, 2, 101–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, L.; Stewart, I.; Almada, P. A Contextual Behavioral Guide to the Self: Theory and Practice; New Harbinger Publications, Inc.: Oakland, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- van den Boogaard, W.M.C.; Komninos, D.S.J.; Vermeij, W.P. Chemotherapy Side-Effects: Not All DNA Damage Is Equal. Cancers 2022, 14, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haroun, R.; Wood, J.N.; Sikandar, S. Mechanisms of cancer pain. Front. Pain Res. 2023, 3, 1030899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luigjes-Huizer, Y.L.; Tauber, N.M.; Humphris, G.; Kasparian, N.A.; Lam, W.W.T.; Lebel, S.; Simard, S.; Smith, A.B.; Zachariae, R.; Afiyanti, Y.; et al. What is the prevalence of fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors and patients? A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Norton, S.; Harrison, A.; McCracken, L.M. In search of the person in pain: A systematic review of conceptualization, assessment methods, and evidence for self and identity in chronic pain. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2015, 4, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; McCracken, L.M. The self in pain. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2025, 62, 101972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, M.; Smith, J.A. The personal experience of chronic benign lower back pain: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Br. J. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Merwin, R.M.; McHugh, L.; Sandoz, E.K.; A-Tjak, J.G.L.; Ruiz, F.J.; Barnes-Holmes, D.; Barnes-Holmes, D.; Bricker, J.B.; Ciarrochi, J.; et al. Report of the ACBS Task Force on the strategies and tactics of contextual behavioral science research. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 20, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Hayes, S.C. The Future of Intervention Science: Process-Based Therapy. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCracken, L.M.; Morley, S. The psychological flexibility model: A basis for integration and progress in psychological approaches to chronic pain management. J. Pain 2014, 15, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, L.; Stapleton, A. Self-as-context. In The Oxford Handbook of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; Twohig, M.P., Levin, M.E., Petersen, J.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 249–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rottenberg, J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert-Williams, N.J.; Storey, L. Psychological flexibility correlates with patient-reported outcomes independent of clinical or sociodemographic characteristics. Support Care Cancer 2016, 24, 2513–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Pistorello, J.; Levin, M.E. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a unified model of behavior change. J. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 40, 976–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; McCracken, L.M. Model and Processes of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Chronic Pain Including a Closer Look at the Self. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2016, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Villatte, M.; Levin, M.; Hildebrandt, M. Open, aware, and active: Contextual approaches as an emerging trend in the behavioral and cognitive therapies. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 7, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, L.M. Personalized pain management: Is it time for process-based therapy for particular people with chronic pain? Eur. J. Pain 2023, 27, 1044–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Norton, S.; McCracken, L.M. Change in “Self-as-Context” (“Perspective-Taking”) occurs in acceptance and commitment therapy for people with chronic pain and is associated with improved functioning. J. Pain 2017, 18, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Norton, S.; Almarzooqi, S.; McCracken, L.M. Preliminary investigation of self-as-context in people with fibromyalgia. Br. J. Pain 2017, 11, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCracken, L.M.; Patel, S.; Scott, W. The role of psychological flexibility in relation to suicidal thinking in chronic pain. Eur. J. Pain 2018, 22, 1774–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickford, J.; Coveney, J.; Baker, J.; Hersh, D. Validating the Changes to Self- identity After Total Laryngectomy. Cancer Nurs. 2019, 42, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morea, J.M.; Friend, R.; Bennett, R.M. Conceptualizing and measuring illness self-concept: A comparison with self-esteem and optimism in predicting fibromyalgia adjustment. Res. Nurs. Health 2008, 31, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karos, K.; Williams, A.C.C.; Meulders, A.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S. Pain as a threat to the social self: A motivational account. Pain 2018, 159, 1690–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I. A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychol. Methods 2018, 23, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Waldorp, L.J.; Mõttus, R.; Borsboom, D. The Gaussian Graphical Model in Cross-Sectional and Time-Series Data. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2018, 53, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S. You want to scale coping but your protocol’ too long: Consider the brief cope. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsou, M.; Panayiotou, G.; Kokkinos, C.M.; Demetriou, A.G. Dimensionality of coping: An empirical contribution to the construct validation of the brief-COPE with a Greek-speaking sample. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliou, V.S.; Michaelides, M.P.; Kasinopoulos, O.; Karekla, M. Psychological Inflexibility in Pain Scale: Greek adaptation, psychometric properties, and invariance testing across three pain samples. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicksell, R.K.; Lekander, M.; Sorjonen, K.; Olsson, G.L. The Psychological Inflexibility in Pain Scale (PIPS)—Statistical properties and model fit of an instrument to assess change processes in pain related disability. Eur. J. Pain 2010, 14, 771.e1–771e.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettle, R.D.; Gird, S.R.; Webster, B.K.; Carrasquillo-Richardson, N.; Swails, J.A.; Burdsal, C.A. The self-as-context scale: Development and preliminary psychometric properties. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2018, 10, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliou, V.S.; Karekla, M.; Michaelides, M.P.; Kasinopoulos, O. Construct validity of the G-CPAQ and its mediating role in pain interference and adjustment. Psychol. Assess. 2018, 30, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi (Version 2.3) [Computer Software]. 2023. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.19.3) [Computer Software]. 2024. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/features/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the LASSO. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Z. Extended Bayesian information criteria for model selection with large model spaces. Biometrika 2008, 95, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, J.; Austin, P.C. Inflation of Type I error rate in multiple regression whenindependent variables are measured with error. Can. J. Stat. 2009, 37, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babyak, M.A. What you see may not be what you get: A brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, G.; Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Perugini, M.; Mõttus, R.; Waldorp, L.J.; Cramer, A.O.J. State of the aRt personality research: A tutorial on network analysis of personality data in R. J. Res. Personal. 2015, 54, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruchterman, T.M.; Reingold, E.M. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Softw. Pract. Exp. 1991, 21, 1129–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I. Package ‘bootnet’, R Package Version 1.5. Available online: https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/bootnet/versions/1.5 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Christodoulou, A.; Michaelides, M.; Karekla, M. Network analysis: A new psychometric approach to examine the underlying ACT model components. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2019, 12, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.F.; Rogge, R.D.; Drake, C.E.; Fogle, C. A fresh lens on psychological flexibility: Using network analysis and the unified flexibility and mindfulness model to uncover paths to wellbeing and distress. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2024, 32, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, D.; Hwang, Y.; Seung, Y.; Yang, E. What Makes Us Strong: Conceptual and Functional Comparisons of Psychological Flexibility and Resilience. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2024, 33, 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karademas, E.C.; Petrakis, C. The relation of intrinsic religiousness to the subjective health of Greek medical inpatients: The mediating role of illness-related coping. Psychol. Health Med. 2009, 14, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, F.; Shali, M.; Shoghi, M.; Joolaee, S. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the self- assessed support needs questionnaire for breast cancer cases. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dědová, M.; Baník, G.; Vargová, L. Coping with cancer: The role of different sources of psychosocial support and the personality of patients with cancer in (mal)adaptive coping strategies. Support Care Cancer 2022, 31, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopman, P.; Rijken, M. Illness perceptions of cancer patients: Relationships with illness characteristics and coping. Psychooncology 2015, 24, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, A.; Karekla, M.; Costantini, G.; Michaelides, M.P. A Network Analysis Approach on the Psychological Flexibility/Inflexibility Model. Behav. Ther. 2023, 54, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosher, C.E.; Krueger, E.; Secinti, E.; Johns, S.A. Symptom experiences in advanced cancer: Relationships to acceptance and commitment therapy constructs. Psychooncology 2021, 30, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.C.; Hofmann, S.G.; Stanton, C.E.; Carpenter, J.K.; Sanford, B.T.; Curtiss, J.E.; Ciarrochi, J. The role of the individual in the coming era of process-based therapy. Behav. Res. Ther. 2019, 117, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, G.B.; Lakhani, A.; Palmer, L.; Sebalj, M.; Rolan, P. A systematic review of qualitative research exploring patient and health professional perspectives of breakthrough cancer pain. Support Care Cancer 2023, 31, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groef, A.; Evenepoel, M.; Van Dijck, S.; Dams, L.; Haenen, V.; Wiles, L.; Catley, M.; Vogelzang, A.; Olver, I.; Hibbert, P.; et al. Feasibility and pilot testing of a personalized eHealth intervention for pain science education and self-management for breast cancer survivors with persistent pain: A mixed-method study. Support Care Cancer 2023, 31, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive and Study Variables | Μ ± SD or n | Score Range or % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 11 | 8.1 |

| Female | 124 | 91.9 |

| Age | ||

| 26 to 35 years old | 8 | 5.9 |

| 36 to 45 years old | 32 | 23.7 |

| 46 to 55 years old | 59 | 43.7 |

| 56 to 65 years old | 25 | 18.5 |

| 66 years old and older | 11 | 8.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 8 | 5.9 |

| In relationship | 7 | 5.2 |

| Married or cohabiting without children | 8 | 5.9 |

| Married or cohabiting with children | 83 | 61.5 |

| Divorced | 21 | 15.6 |

| Widow/widower | 7 | 5.2 |

| Other status | 1 | 0.7 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employee | 69 | 51.1 |

| Unemployed | 16 | 11.9 |

| University student | 2 | 1.5 |

| Retired | 25 | 18.5 |

| Household | 21 | 15.6 |

| Do not wish to answer | 1 | 0.7 |

| Other status | 1 | 0.7 |

| Time since diagnosis | ||

| Within the last 5 years | 84 | 62.6 |

| 6 to 9 years | 29 | 21.7 |

| 10 years and more | 21 | 15.7 |

| Brief—COPE | 66.5 ± 12.3 | 28–101 |

| Active coping | 23.3 ± 4.84 | 8–32 |

| Behavioral disengagement | 2.66 ± 1.30 | 2–8 |

| Substance use | 2.24 ± 0.86 | 2–8 |

| Seeking support | 9.83 ± 3.19 | 4–16 |

| Religion | 4.97 ± 2.18 | 2–8 |

| Humor | 5.64 ± 2.13 | 2–8 |

| Avoidance | 8.69 ± 2.60 | 4–16 |

| Expression of negative feelings | 9.15 ± 2.57 | 4–14 |

| Psychological Inflexibility in Pain Scale | 48.2 ± 17.3 | 17–84 |

| Self-as-context scale | 49.4 ± 10.8 | 16–70 |

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. G-PIPS-II | - | |||||||||

| 2. SACS | 0.04 | - | ||||||||

| 3. Active coping subscale | 0.36 *** | 0.40 *** | - | |||||||

| 4. Behavioral disengagement subscale | 0.31 *** | 0.03 | −0.04 | - | ||||||

| 5. Substance use subscale | 0.23 ** | −0.28 *** | −0.14 | 0.55 *** | - | |||||

| 6. Seeking support subscale | 0.20 * | −0.04 | 0.43 *** | −0.04 | −0.03 | - | ||||

| 7. Religion subscale | 0.23 ** | 0.08 | 0.30 *** | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.29 *** | - | |||

| 8. Humor subscale | 0.01 | 0.44 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.19 * | 0.17 * | - | ||

| 9. Avoidance subscale | 0.36 *** | 0.15 | 0.51 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.14 | 0.30 *** | 0.10 | 0.25 ** | - | |

| 10. Expression of negative feelings Subscale | 0.35 *** | 0.11 | 0.43 *** | 0.22 * | 0.15 | 0.44 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.35 *** | - |

| Standardized Beta | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Β | t | P | R2 | Adj. R2 | F Change | Sig. F Change (p) |

| Dependent variable: COPE: Active coping | |||||||

| Gender | −0.20 | −0.13 | 0.90 | ||||

| Age | −0.45 | −1.12 | 0.26 | ||||

| Marital status | 0.17 | 0.47 | 0.64 | ||||

| Employment status | −0.31 | −1.24 | 0.22 | ||||

| Type of cancer | −0.15 | −1.60 | 0.11 | ||||

| Time since diagnosis | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.91 | ||||

| Stage of cancer | −0.05 | −0.26 | 0.80 | ||||

| Psychological inflexibility in pain scale | 0.10 | 4.67 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 7.35 | <0.001 |

| Self-as-context scale | 0.18 | 5.12 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 7.35 | <0.001 |

| Dependent variable: COPE: Behavioral disengagement | |||||||

| Gender | 0.36 | 0.84 | 0.40 | ||||

| Age | −0.03 | −0.22 | 0.83 | ||||

| Marital status | −0.03 | −0.28 | 0.78 | ||||

| Employment status | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.10 | ||||

| Type of cancer | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.32 | ||||

| Time since diagnosis | −0.03 | −0.76 | 0.45 | ||||

| Stage of cancer | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.92 | ||||

| Psychological inflexibility in pain scale | 0.02 | 3.45 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 1.91 | 0.06 |

| Self-as-context scale | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.68 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 1.91 | 0.06 |

| Dependent variable: COPE: Substance use | |||||||

| Gender | 0.22 | 0.76 | 0.45 | ||||

| Age | −0.04 | −0.46 | 0.65 | ||||

| Marital status | −0.04 | −0.58 | 0.57 | ||||

| Employment status | 0.07 | 1.57 | 0.12 | ||||

| Type of cancer | −0.00 | −0.27 | 0.79 | ||||

| Time since diagnosis | −0.01 | −0.46 | 0.65 | ||||

| Stage of cancer | −0.00 | −0.12 | 0.91 | ||||

| Psychological inflexibility in pain scale | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.008 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 1.68 | 0.11 |

| Self-as-context scale | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 2.61 | 0.01 |

| Dependent variable: COPE: Seeking support | |||||||

| Gender | −0.23 | −0.20 | 0.84 | ||||

| Age | −0.19 | −0.55 | 0.58 | ||||

| Marital status | −0.23 | −0.87 | 0.38 | ||||

| Employment status | −0.03 | −0.16 | 0.88 | ||||

| Type of cancer | −0.03 | 0.41 | 0.69 | ||||

| Time since diagnosis | −0.23 | −2.81 | 0.006 | ||||

| Stage of cancer | 0.06 | 0.37 | 0.71 | ||||

| Psychological inflexibility in pain scale | 0.03 | 2.12 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 2.14 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Self-as-context scale | −0.01 | −0.36 | 0.72 | 0.06 | 1.91 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Dependent variable: COPE: Religion | |||||||

| Gender | 0.54 | −0.70 | 0.49 | ||||

| Age | −0.15 | −0.61 | 0.54 | ||||

| Marital status | −0.22 | −1.22 | 0.22 | ||||

| Employment status | −0.08 | −0.66 | 0.51 | ||||

| Type of cancer | 0.06 | 1.23 | 0.22 | ||||

| Time since diagnosis | −0.08 | −1.52 | 0.13 | ||||

| Stage of cancer | −0.02 | −0.15 | 0.88 | ||||

| Psychological inflexibility in pain scale | 0.03 | 2.40 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 1.98 | 0.05 |

| Self-as-context scale | 0.02 | 0.95 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 1.86 | 0.06 |

| Dependent variable: COPE: Humor | |||||||

| Gender | −0.73 | −1.04 | 0.30 | ||||

| Age | −0.33 | −1.53 | 0.13 | ||||

| Marital status | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.77 | ||||

| Employment status | −0.001 | −0.01 | 0.99 | ||||

| Type of cancer | −0.11 | −2.51 | 0.013 | ||||

| Time since diagnosis | −0.002 | −0.04 | 0.97 | ||||

| Stage of cancer | 0.05 | 0.57 | 0.57 | ||||

| Psychological inflexibility in pain scale | 0.002 | 0.19 | 0.85 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.49 | 0.87 |

| Self-as-context scale | 0.09 | 5.81 | <0.001 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 4.29 | <0.001 |

| Dependent variable: COPE: Self-distraction | |||||||

| Gender | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.81 | ||||

| Age | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.94 | ||||

| Marital status | −0.09 | −0.43 | 0.67 | ||||

| Employment status | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.89 | ||||

| Type of cancer | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.34 | ||||

| Time since diagnosis | −0.007 | −0.11 | 0.91 | ||||

| Stage of cancer | −0.09 | −0.77 | 0.44 | ||||

| Psychological inflexibility in pain scale | 0.05 | 4.01 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 2.62 | 0.01 |

| Self-as-context scale | 0.03 | 1.53 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 2.62 | 0.01 |

| Dependent variable: COPE: Self-blame | |||||||

| Gender | 1.21 | 1.39 | 0.17 | ||||

| Age | −0.32 | −1.20 | 0.23 | ||||

| Marital status | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.98 | ||||

| Employment status | −0.04 | −0.29 | 0.77 | ||||

| Type of cancer | −0.03 | −0.59 | 0.56 | ||||

| Time since diagnosis | −0.04 | −0.61 | 0.55 | ||||

| Stage of cancer | 0.04 | 0.38 | 0.71 | ||||

| Psychological inflexibility in pain scale | 0.05 | 4.23 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 3.20 | 0.002 |

| Self-as-context scale | 0.03 | 1.33 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 3.06 | 0.002 |

| Network Weights | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total G-PIPS-II | BRIE (Active Coping) | SACS1 | SACS2 | SACS3 | SACS4 | SACS5 | SACS6 | SACS7 | SACS8 | SACS9 | SACS10 |

| Total G-PIPS-II | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.174 | 0.238 |

| BRIE (Active Coping) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.352 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.076 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.073 | 0.000 |

| SACS1 | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.045 | 0.288 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.044 | 0.006 | 0.054 | 0.145 | −0.103 |

| SACS2 | 0.000 | 0.352 | 0.045 | 0.000 | 0.325 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.225 | −0.034 | 0.000 | 0.167 | 0.000 |

| SACS3 | 0.000 | 0.029 | 0.288 | 0.325 | 0.000 | 0.340 | 0.000 | 0.043 | 0.085 | 0.025 | 0.000 | −0.026 |

| SACS4 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.340 | 0.000 | 0.202 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.111 | 0.084 | 0.074 |

| SACS5 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.202 | 0.000 | 0.302 | 0.232 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| SACS6 | 0.000 | 0.076 | 0.044 | 0.225 | 0.043 | 0.000 | 0.302 | 0.000 | 0.162 | 0.058 | 0.182 | −0.030 |

| SACS7 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.006 | −0.034 | 0.085 | 0.000 | 0.232 | 0.162 | 0.000 | 0.110 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| SACS8 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 0.025 | 0.111 | 0.000 | 0.058 | 0.110 | 0.000 | 0.334 | 0.148 |

| SACS9 | 0.174 | 0.073 | 0.145 | 0.167 | 0.000 | 0.084 | 0.000 | 0.182 | 0.000 | 0.334 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| SACS10 | 0.238 | 0.000 | −0.103 | 0.000 | −0.026 | 0.074 | 0.000 | −0.030 | 0.000 | 0.148 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balta, E.; Koliouli, F.; Canellopoulos, L.V.; Vasiliou, V.S. The Role of Self-as-Context as a Self-Based Process of Change in Cancer-Related Pain: Insights from a Network Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2722. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212722

Balta E, Koliouli F, Canellopoulos LV, Vasiliou VS. The Role of Self-as-Context as a Self-Based Process of Change in Cancer-Related Pain: Insights from a Network Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(21):2722. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212722

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalta, Evangelia, Flora Koliouli, Lissy Vassiliki Canellopoulos, and Vasilis S. Vasiliou. 2025. "The Role of Self-as-Context as a Self-Based Process of Change in Cancer-Related Pain: Insights from a Network Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 21: 2722. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212722

APA StyleBalta, E., Koliouli, F., Canellopoulos, L. V., & Vasiliou, V. S. (2025). The Role of Self-as-Context as a Self-Based Process of Change in Cancer-Related Pain: Insights from a Network Analysis. Healthcare, 13(21), 2722. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212722