Knowledge and Treatment of Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia Versus Gout Among Physicians in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Sampling Technique and Participants

2.3. Definition of General Practitioner and Physician Without Specialty Training

2.4. Study Measurements

2.5. Questionnaire Criteria

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Physician Demographics

3.2. General Knowledge and Practice

3.3. Knowledge and Demographics

3.4. Practice and Demographics

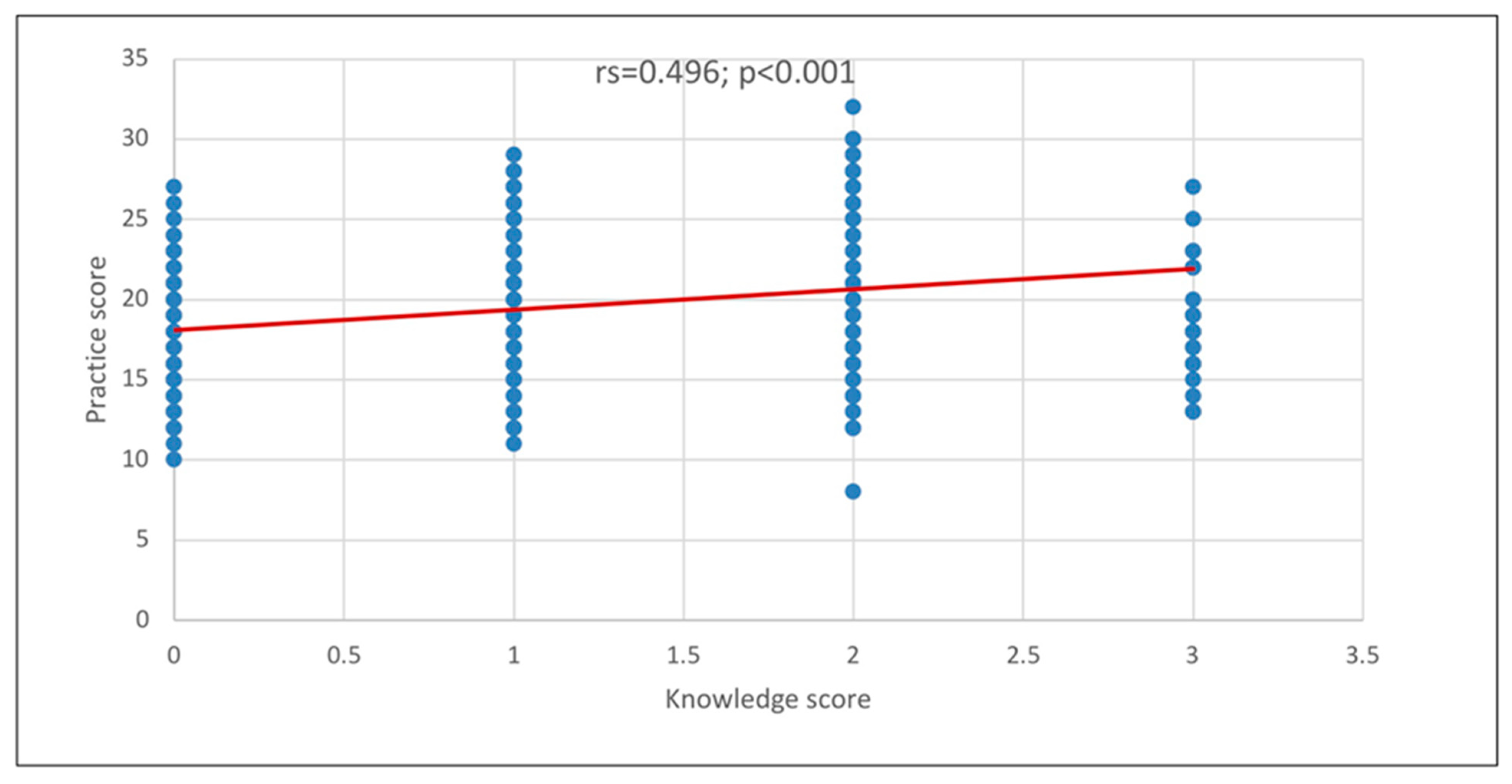

3.5. Knowledge and Practice Level

3.6. Practice Scores and Practice Level

3.7. Knowledge and Practice Scores and Specialties

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge About AH

4.2. Significant Factors Contributing to Knowledge

4.3. Low Knowledge Scores of Rheumatologists

4.4. Practice Related to AH or Gout

4.5. Significant Factors in Practice

4.6. Management of Patients with Gout

4.7. Recommended Dietary Patterns

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Arfaj, A.S. Hyperuricemia in Saudi Arabia. Rheumatol. Int. 2001, 20, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Xie, L.; Yang, B.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, Z.; Gao, J. Hyperuricemia and its related diseases: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, T.; Richette, P. Definition of hyperuricemia and gouty conditions. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2014, 26, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehlin, M.; Jacobsson, L.; Roddy, E. Global epidemiology of gout: Prevalence, incidence, treatment patterns and risk factors. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohrag, M.; AlFaifi, M.M.; AlAhmari, M.A.; AlSuwayj, A.H.; AlShehri, A.A.; AlKhamis, A.M.; AlKhayal, M.M.; Oraibi, O.; Somaili, M.; AlZahrani, K. Knowledge and Awareness Level among Adults in Saudi Arabia, Regarding Gout Risk Factors and Prevention Methods. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 13, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Almuqrin, A.; Alshuweishi, Y.A.; Alfaifi, M.; Daghistani, H.; Al-Sheikh, Y.A.; Alfhili, M.A. Prevalence and association of hyperuricemia with liver function in Saudi Arabia: A large cross-sectional study. Ann. Saudi Med. 2024, 44, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.D.; Clarke, B.D.; Roddy, E.; Galloway, J.B. Improving outcomes for patients hospitalized with gout: A systematic review. Rheumatology 2021, 61, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National AIDS Program. Ministry of Health (Saudi Arabia). In Statistical Yearbook 2023; NAP: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hazra, A. Using the confidence interval confidently. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 4125–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS). Saudi Board Major Specialty and Diploma Programs Matching Booklet; SCFHS: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alraqibah, E.A.; Alharbi, F.M.; Alharbi, N.S.; Aldekhail, M.I.; Alahmadi, K.M.; A Alresheedi, M.; AlKhattaf, M.I. Knowledge and Practice of Primary Health Care Providers in the Management of Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia and Gout in the Qassim Region of Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e30976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FitzGerald, J.D.; Dalbeth, N.; Mikuls, T.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Guyatt, G.; Abeles, A.M.; Gelber, A.C.; Harrold, L.R.; Khanna, D.; King, C.; et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout. Arthritis Care Res. 2020, 72, 744–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Xu, M.; Yokose, C.; Rai, S.K.; Pillinger, M.H.; Choi, H.K. Contemporary Prevalence of Gout and Hyperuricemia in the United States and Decadal Trends: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007–2016. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, N.A.; Hassan, A.H. Knowledge and practice in the management of asymptomatic hyperuricemia among primary health care physicians in Jeddah, Western Region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward hyperuricemia among healthcare workers in Shandong, China. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawhari, I.; AlQahtani, O.A.; Alqahtani, M.S.; Alshehri, R.M.; Alsairy, M.A.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Aljaber, A.M.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Alqahtani, A.M.; Alahmary, M.A.; et al. Assessment of Primary Healthcare Providers’ Knowledge and Practices in Addressing Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia and Gout in the Asir Region of Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e51745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwaskar, M.; Sholapuri, D. An Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Physicians in the Management of Hyperuricemia in India: A Questionnaire-Based Study. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2021, 69, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alenazi, H.; Almutairi, R.; Alnashri, H.; Almohammadi, R.; Alenzi, F. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Towards Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia and Gout Among Family Medicine Residents in King Saud Medical City in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 11, 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautner, J.; Sautner, T. Compliance of Primary Care Providers with Gout Treatment Recommendations-Lessons to Learn: Results of a Nationwide Survey. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, S.K.; Choi, H.K.; Choi, S.H.J.; Townsend, A.F.; Shojania, K.; De Vera, M.A. Key barriers to gout care: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Rheumatology 2018, 57, 1282–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Pandya, B.J.; Choi, H.K. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63, 3136–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Fitzgerald, J.D.; Khanna, P.P.; Bae, S.; Singh, M.K.; Neogi, T.; Pillinger, M.H.; Merill, J.; Lee, S.; Prakash, S.; et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: Systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res. 2012, 64, 1431–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edar, M.F.J.Y.; Li-Yu, J. Clinical practice on gout management among Filipino general care practitioners. J. Med. Univ. St. Tomas 2017, 1, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, I.; Hamijoyo, L.; Moeliono, M. A survey on the clinical diagnosis and management of gout among general practitioners in Bandung. Indones. J. Rheumatol. 2013, 4, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

| Study Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| ● 24–34 years | 440 (59.1%) |

| ● 35–44 years | 164 (22.0%) |

| ● 45–54 years | 104 (14.0%) |

| ● 55–64 years | 26 (03.5%) |

| ● >64 years | 10 (01.3%) |

| Gender | |

| ● Male | 343 (46.1%) |

| ● Female | 401 (53.9%) |

| Region of practice | |

| ● Central Region | 172 (31.3%) |

| ● Southern Region | 87 (11.7%) |

| ● Western Region | 344 (46.2%) |

| ● Eastern Region | 104 (14.0%) |

| ● Northern Region | 37 (05.0%) |

| Medical specialty | |

| ● General practitioner | 233 (31.3%) |

| ● Rheumatology | 54 (07.3%) |

| ● Internal medicine | 147 (19.8%) |

| ● Emergency medicine | 71 (09.5%) |

| ● Family medicine | 184 (24.7%) |

| ● Orthopedic surgery | 55 (07.4%) |

| Current level of medical training/practice | |

| ● Physician without specialty training | 311 (41.8%) |

| ● Resident | 207 (27.8%) |

| ● Fellow | 66 (08.9%) |

| ● Specialist/ Registrar | 91 (12.2%) |

| ● Consultant | 69 (09.3%) |

| Years of experience (after internship completion) | |

| ● <5 years | 383 (51.5%) |

| ● 5–10 years | 240 (32.3%) |

| ● >10 years | 121 (16.3%) |

| In the past three years, have you attended any CME activities specifically focused on AH or gout? | |

| ● Yes | 437 (58.7%) |

| ● No | 307 (41.3%) |

| In the past three years, have you actively sought out and reviewed information about AH or gout (e.g., through medical journals, online resources, textbooks)? | |

| ● Yes | 497 (66.8%) |

| ● No | 247 (33.2%) |

| Are you aware of the latest 2020 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for the management of gout? | |

| ● Yes | 436 (58.6%) |

| ● No | 308 (41.4%) |

| Knowledge Items * Indicates the Correct Answer | N (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. What is the correct threshold for serum uric acid levels defining AH? [Correct answer: Serum uric acid level is >7 mg/dL in males and >6 mg/dL in females] * | 364 (48.9%) |

| [Serum uric acid level is >6 mg/dL in both males and females] | 168 (22.6%) |

| [Serum uric acid level is >6 mg/dL in males and >7 in females] | 90 (12.1%) |

| [I do not know] | 122 (16.4%) |

| 2. AH always progresses to gouty arthritis [Correct answer: incorrect] * | 407(54.7%) |

| [correct] | 204 (27.4%) |

| [I do not know] | 133 (17.9%) |

| 3. AH always needs treatment [Correct answer: incorrect] * | 411 (55.2%) |

| [correct] | 225 (30.2%) |

| [I do not know] | 108 (14.6%) |

| Total knowledge score (mean ± SD) | 1.59 ± 1.09 |

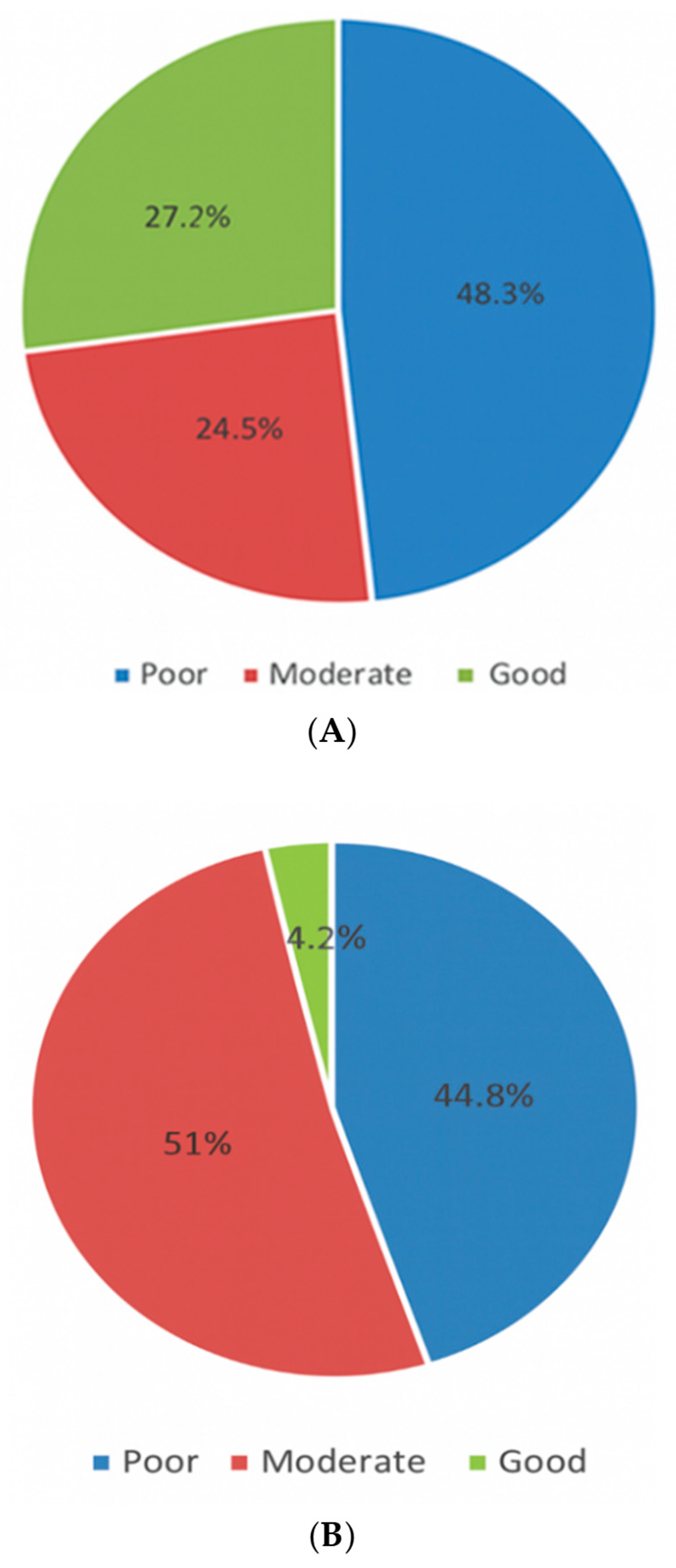

| Level of knowledge about AH | |

| ● Poor | 359 (48.3%) |

| ● Moderate | 182 (24.5%) |

| ● Good | 203 (27.3%) |

| Practice items * Indicates the correct answer | |

| 374 (50.3%) |

| 219 (29.4%) |

| 233 (31.3%) |

| 221 (29.7%) |

| Under which of the following conditions would you typically initiate ULT? (Select all that apply) | |

| 569 (76.5%) |

| 519 (69.8%) |

| 403 (54.2%) |

| 390 (52.4%) |

| 318 (42.7%) |

| 242 (32.5%) |

| 392 (52.7%) |

| 346 (46.5%) |

| 446 (59.9%) |

| 248 (33.3%) |

| 368 (49.5%) |

| |

| [I acknowledge the importance of diet and lifestyle modifications but have limited time for in-depth discussions. I may provide basic guidance or handouts] | 303 (40.7%) |

| [Diet and lifestyle modifications are not routinely addressed during consultations] | 73 (9.8%) |

| Which of the following diet items would you recommend a patient with gout to AVOID? (Select all that apply) | |

| 437 (58.7%) |

| 310 (41.7%) |

| 398 (53.5%) |

| 380 (51.1%) |

| 367 (49.3%) |

| 377 (50.7%) |

| 537 (72.2%) |

| 537 (72.2%) |

| 603 (81.0%) |

| 680 (91.4%) |

| 675 (90.7%) 45 (6.04%) |

| Which of the following diet items would you recommend a patient with gout to LIMIT? (Select all that apply) | |

| 455 (61.2%) |

| 523 (70.3%) |

| 316 (42.5%) |

| 234 (31.5%) |

| 489 (65.7%) |

| 255 (34.3%) |

| 251 (33.7%) |

| 251 (33.7%) |

| 214 (28.8%) |

| 607 (81.6%) |

| 619 (83.2%) |

| 63 (8.4%) |

| Total practice score (mean ± SD) | 19.9 ± 4.16 |

| Level of practice | |

| ● Poor | 333 (44.8%) |

| ● Moderate | 380 (51.0%) |

| ● Good | 31 (4.2%) |

| Factor | Knowledge Score (3) Mean ± SD | Z/H-Test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group a | |||

| ● <35 years | 1.44 ± 1.07 | 4.518 | <0.001 ** |

| ● ≥35 years | 1.81 ± 1.09 | ||

| Gender a | |||

| ● Male | 1.73 ± 1.08 | 3.380 | 0.001 ** |

| ● Female | 1.46 ± 1.09 | ||

| Region of practice a | |||

| ● Inside Western Region | 1.72 ± 1.05 | 2.964 | 0.003 ** |

| ● Outside Western Region | 1.48 ± 1.12 | ||

| Medical specialty b | |||

| ● General practitioner | 1.33 ± 1.09 | 34.403 | <0.001 ** |

| ● Rheumatology | 1.35 ± 0.91 | ||

| ● Internal medicine | 1.72 ± 1.09 | ||

| ● Emergency medicine | 1.46 ± 1.07 | ||

| ● Family medicine | 1.78 ± 1.05 | ||

| ● Orthopedic surgery | 2.05 ± 1.11 | ||

| Current level of medical training/practice b | |||

| ● Physician without specialty training | 1.42 ± 1.06 | 31.791 | <0.001 ** |

| ● Resident | 1.65 ± 1.10 | ||

| ● Fellow | 1.35 ± 0.97 | ||

| ● Specialist/Registrar | 1.81 ± 1.13 | ||

| ● Consultant | 2.12 ± 1.02 | ||

| Years of experience (after internship completion) a | |||

| ● <5 years | 1.42 ± 1.07 | 4.417 | <0.001 ** |

| ● ≥5 years | 1.77 ± 1.09 | ||

| In the past three years, have you attended any CME activities specifically focused on AH or gout? a | |||

| ● Yes | 1.53 ± 1.08 | 1.765 | 0.078 |

| ● No | 1.67 ± 1.09 | ||

| In the three years, have you actively sought out and reviewed information about AH or gout? a | |||

| ● Yes | 1.70 ± 1.09 | 3.997 | <0.001 ** |

| ● No | 1.36 ± 1.07 | ||

| Are you aware of the latest 2020 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for the management of gout? a | |||

| ● Yes | 1.63 ± 1.07 | 1.065 | 0.287 |

| ● No | 1.54 ± 1.12 |

| Factor | Practice Score (37) Mean ± SD | Z/H-Test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group a | |||

| ● <35 years | 19.2 ± 3.91 | 5.643 | <0.001 ** |

| ● ≥35 years | 20.9 ± 4.29 | ||

| Gender a | |||

| ● Male | 20.4 ± 4.38 | 2.882 | 0.004 ** |

| ● Female | 19.5 ± 3.92 | ||

| Region of practice a | |||

| ● Inside Western Region | 20.3 ± 4.29 | 2.581 | 0.010 ** |

| ● Outside Western Region | 19.5 ± 4.02 | ||

| Medical specialty b | |||

| ● General practitioner | 18.7 ± 3.50 | 26.529 | <0.001 ** |

| ● Rheumatology | 19.6 ± 3.97 | ||

| ● Internal medicine | 20.4 ± 4.18 | ||

| ● Emergency medicine | 20.0 ± 4.35 | ||

| ● Family medicine | 20.6 ± 4.52 | ||

| ● Orthopedic surgery | 21.3 ± 4.38 | ||

| Current level of medical training/practice b | |||

| ● Physician without specialty training | 18.9 ± 3.92 | 45.425 | <0.001 ** |

| ● Resident | 20.4 ± 4.32 | ||

| ● Fellow | 19.2 ± 3.61 | ||

| ● Specialist/Registrar | 20.7 ± 3.96 | ||

| ● Consultant | 22.2 ± 4.24 | ||

| Years of experience (after internship completion) a | |||

| ● <5 years | 19.3 ± 4.03 | 4.172 | <0.001 ** |

| ● ≥5 years | 20.6 ± 4.21 | ||

| In the past three years, have you attended any CME activities specifically focused on AH or gout? a | |||

| ● Yes | 19.5 ± 4.23 | 3.353 | 0.001 ** |

| ● No | 20.4 ± 4.02 | ||

| In the three years, have you actively sought out and reviewed information about AH or gout? a | |||

| ● Yes | 20.3 ± 4.19 | 3.267 | 0.001 ** |

| ● No | 19.1 ± 3.99 | ||

| Are you aware of the latest 2020 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for the management of gout? a | |||

| ● Yes | 20.3 ± 4.48 | 2.017 | 0.044 ** |

| ● No | 19.4 ± 3.61 |

| (I) Level of Medical Training/Practice | (J) Level of Medical Training/Practice | Mean Difference (I–J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| Physician without specialty training | Specialist/Registrar | −0.39518 * | 0.12773 | 0.021 | −0.7548 | −0.0356 |

| Consultant | −0.69794 * | 0.14262 | 0.000 | −1.0995 | −0.2964 | |

| Resident | Consultant | −0.46860 * | 0.14898 | 0.017 | −0.8880 | −0.0492 |

| Fellow | Consultant | −0.76746 * | 0.18452 | 0.000 | −1.2870 | −0.2479 |

| (I) Level of Medical Training/Practice | (J) Level of Medical Training/Practice | Mean Difference (I–J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| Physician without specialty training | Resident | −1.43632 * | 0.36271 | 0.001 | −2.4575 | −0.4151 |

| Specialist/Registrar | −1.73732 * | 0.48191 | 0.003 | −3.0941 | −0.3805 | |

| Consultant | −3.27690 * | 0.53807 | 0.000 | −4.7918 | −1.7620 | |

| Resident | Consultant | −1.84058 * | 0.56208 | 0.011 | −3.4231 | −0.2580 |

| Fellow | Consultant | −2.98946 * | 0.69619 | 0.000 | −4.9496 | −1.0294 |

| Specialty | N (%) | Knowledge Score Mean ± SD | Practice Score Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthopedic | |||

| ● Physician without specialty training | 07 (12.7%) | 1.86 ± 1.21 | 22.6 ± 4.69 |

| ● Resident | 18 (32.7%) | 2.56 ± 0.70 | 23.2 ± 4.09 |

| ● Fellow | 03 (05.5%) | 1.00 ± 1.00 | 15.3 ± 4.04 |

| ● Specialist/Registrar | 17 (30.9%) | 1.71 ± 1.21 | 19.0 ± 2.35 |

| ● Consultant | 10 (18.2%) | 2.20 ± 1.23 | 22.4 ± 4.84 |

| Family medicine | |||

| ● Physician without specialty training | 35 (19.0%) | 1.94 ± 0.91 | 19.6 ± 4.96 |

| ● Resident | 85 (46.2%) | 1.80 ± 1.06 | 20.8 ± 4.55 |

| ● Fellow | 17 (09.2%) | 1.35 ± 0.99 | 19.3 ± 4.24 |

| ● Specialist/Registrar | 28 (15.2%) | 1.61 ± 1.19 | 21.2 ± 4.17 |

| ● Consultant | 19 (10.3%) | 2.05 ± 0.97 | 21.6 ± 4.09 |

| Internal medicine | |||

| ● Physician without specialty training | 56 (38.1%) | 1.23 ± 1.06 | 19.1 ± 4.09 |

| ● Resident | 31 (21.1%) | 1.71 ± 1.07 | 19.7 ± 4.36 |

| ● Fellow | 16 (10.9%) | 1.39 ± 0.95 | 20.4 ± 3.46 |

| ● Specialist/Registrar | 23 (15.6%) | 2.39 ± 0.84 | 22.4 ± 3.57 |

| ● Consultant | 21 (14.3%) | 2.33 ± 0.97 | 22.7 ± 3.79 |

| General practitioner | 233 (100%) | 1.33 ± 1.09 | 18.7 ± 3.50 |

| Rheumatology | |||

| ● Physician without specialty training | 11 (20.4%) | 1.00 ± 0.77 | 16.8 ± 2.56 |

| ● Resident | 11 (20.4%) | 1.00 ± 1.00 | 19.1 ± 3.24 |

| ● Fellow | 15 (27.8%) | 1.00 ± 0.65 | 19.6 ± 2.75 |

| ● Specialist/Registrar | 07 (13.0%) | 1.43 ± 0.79 | 18.0 ± 4.73 |

| ● Consultant | 10 (18.5%) | 1.60 ± 0.52 | 24.6 ± 2.79 |

| Emergency medicine | |||

| ● Physician without specialty training | 21 (29.6%) | 1.05 ± 0.74 | 19.5 ± 4.52 |

| ● Resident | 30 (42.3%) | 1.20 ± 0.85 | 20.7 ± 4.51 |

| ● Fellow | 08 (11.3%) | 0.88 ± 0.64 | 18.6 ± 4.10 |

| ● Specialist/Registrar | 07 (09.9%) | 1.43 ± 0.79 | 20.1 ± 3.53 |

| ● Consultant | 05 (07.0%) | 1.40 ± 0.89 | 20.4 ± 5.03 |

| Factor | β | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| In the past three years, have you attended any CME activities specifically focused on AH or gout? a | 1.368 | 0.738–1.998 | <0.001 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alammari, Y.M.; Albassam, A.; Alorainy, M.; Alibrahim, F.; Alshahwan, A.; Alaskar, A.; Qutob, R.A.; Alhajery, M.; Alotay, A.; Daghistani, Y.; et al. Knowledge and Treatment of Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia Versus Gout Among Physicians in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2719. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212719

Alammari YM, Albassam A, Alorainy M, Alibrahim F, Alshahwan A, Alaskar A, Qutob RA, Alhajery M, Alotay A, Daghistani Y, et al. Knowledge and Treatment of Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia Versus Gout Among Physicians in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare. 2025; 13(21):2719. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212719

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlammari, Yousef M., Abdulmohsen Albassam, Mohammad Alorainy, Faisal Alibrahim, Abdulrahman Alshahwan, Abdullah Alaskar, Rayan A. Qutob, Mohammad Alhajery, Abdulwahed Alotay, Yassir Daghistani, and et al. 2025. "Knowledge and Treatment of Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia Versus Gout Among Physicians in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey" Healthcare 13, no. 21: 2719. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212719

APA StyleAlammari, Y. M., Albassam, A., Alorainy, M., Alibrahim, F., Alshahwan, A., Alaskar, A., Qutob, R. A., Alhajery, M., Alotay, A., Daghistani, Y., Alanazi, A., & Alshehri, I. (2025). Knowledge and Treatment of Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia Versus Gout Among Physicians in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare, 13(21), 2719. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212719