Prevalence, Geographic Variations, and Determinants of Pain Among Older Adults in China: Findings from the National Urban and Rural Elderly Population (UREP) Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

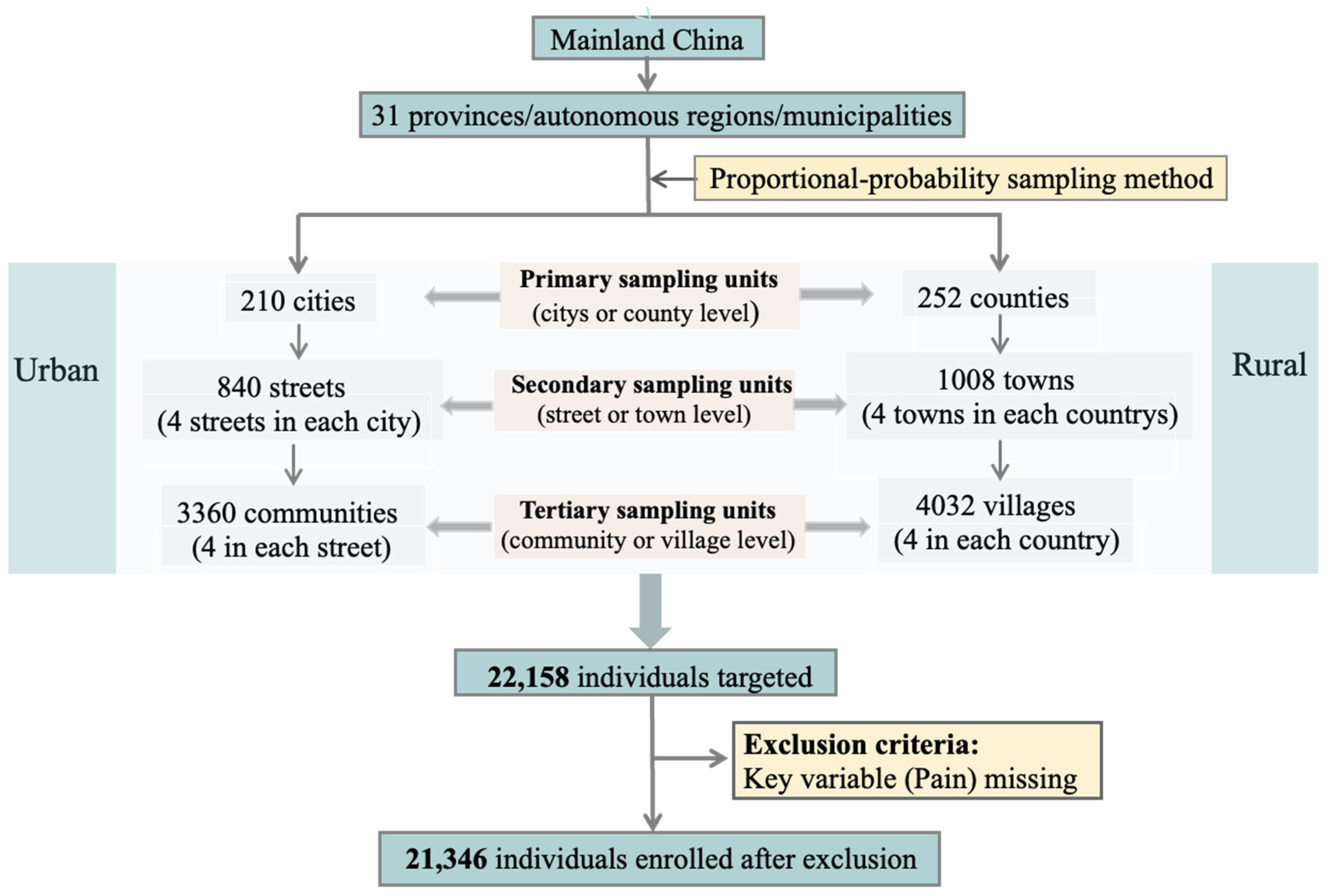

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Sampling and Data Collection

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Prevalence and Distribution of Pain

3.3. Geographic Variations in Pain Prevalence

3.4. Factors Associated with Pain

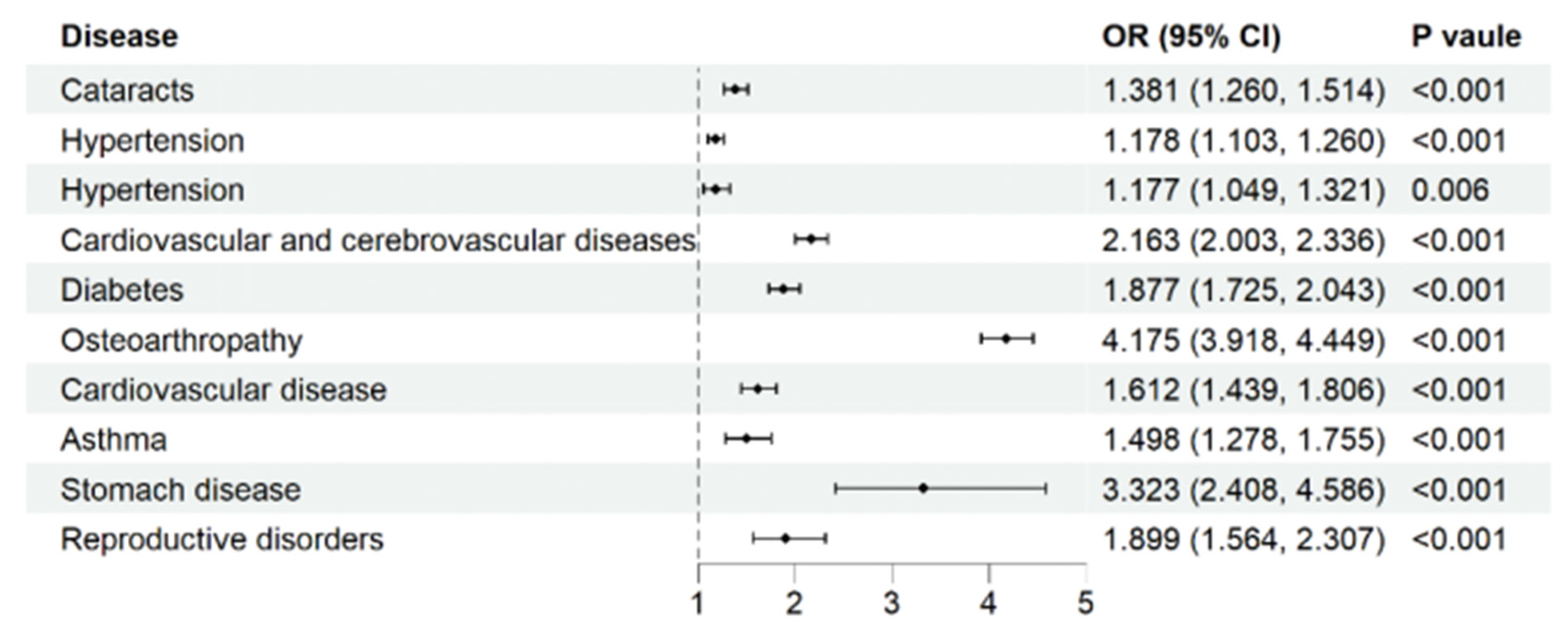

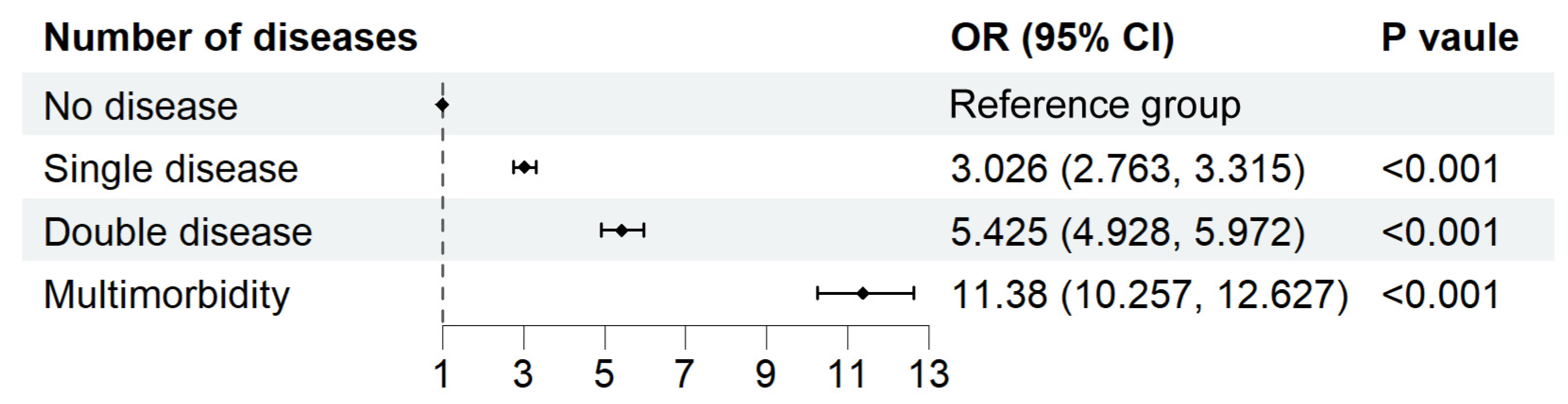

3.5. Chronic Diseases and Pain

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Province | Number of People with Pain | Prevalence of Pain (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Anhui | 616 | 57.46 (54.50, 60.42) |

| Beijing | 168 | 50.76 (45.37, 56.14) |

| Fujian | 243 | 47.28 (42.96, 51.59) |

| Gansu | 243 | 72.75 (67.98, 77.53) |

| Guangdong | 746 | 57.08 (54.39, 59.76) |

| Guangxi | 515 | 64.21 (60.90, 67.53) |

| Guizhou | 317 | 58.38 (54.23, 62.53) |

| Hainan | 97 | 72.39 (64.82, 79.96) |

| Hebei | 534 | 52.35 (49.29, 55.42) |

| Henan | 766 | 55.87 (53.24, 58.50) |

| Heilongjiang | 251 | 46.48 (42.27, 50.69) |

| Hubei | 588 | 62.96 (59.86, 66.05) |

| Hunan | 682 | 60.19 (57.34, 63.04) |

| Jilin | 194 | 52.86 (47.75, 57.97) |

| Jiangsu | 750 | 49.37 (46.86, 51.89) |

| Jiangxi | 355 | 57.82 (53.91, 61.72) |

| Liaoning | 363 | 43.27 (39.91, 46.62) |

| Inner Mongolia | 214 | 67.30 (62.14, 72.45) |

| Ningxia | 66 | 72.53 (63.36, 81.70) |

| Qinghai | 56 | 61.54 (51.54, 71.53) |

| Shandong | 882 | 50.49 (48.14, 52.83) |

| Shanxi | 324 | 65.06 (60.87, 69.25) |

| Shaanxi | 340 | 62.73 (58.66, 66.80) |

| Shanghai | 161 | 38.98 (34.28, 43.69) |

| Sichuan | 1000 | 65.10 (62.72, 67.49) |

| Tianjin | 106 | 55.50 (48.45, 62.55) |

| Xizang | 50 | 53.76 (43.63, 63.90) |

| Xinjiang | 118 | 53.39 (46.82, 59.97) |

| Yunnan | 428 | 64.75 (61.11, 68.39) |

| Zhejiang | 524 | 54.70 (51.55, 57.85) |

| Chongqing | 369 | 60.29 (56.42, 64.17) |

References

- Kumar, K.H.; Elavarasi, P. Definition of pain and classification of pain disorders. J. Adv. Clin. Res. Insights 2016, 3, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, M.M. Defining pain: Past, present, and future. Pain 2017, 158, 761–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.P.; Vase, L.; Hooten, W.M. Chronic pain: An update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet 2021, 397, 2082–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajat, C.; Stein, E. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: A narrative review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dueñas, M.; Ojeda, B.; Salazar, A.; Mico, J.A.; Failde, I. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J. Pain Res. 2016, 9, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.S.; McGee, S.J. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Su, B.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, C.; Vellas, B.; Michel, J.-P.; Shao, R. Foundations and implications of Human Aging Omics: A framework for identifying cumulative health risks from embryo to senescence. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 3184–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjistavropoulos, T.; Fine, P.G. Chronic pain in older persons: Prevalence, assessment and management. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 2006, 16, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, C.B.; Le, T.K.; Zhou, X.; Johnston, J.A.; Dworkin, R.H. The prevalence of chronic pain in united states adults: Results of an internet-based survey. J. Pain 2010, 11, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, A.; Croft, P.; Langford, R.; Donaldson, L.J.; Jones, G.T. Prevalence of chronic pain in the uk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.X.; Patel, K.; Miaskowski, C.; Maravilla, I.; Schear, S.; Garrigues, S.; Thompson, N.; Auerbach, A.D.; Ritchie, C.S. Prevalence and characteristics of moderate to severe pain among hospitalized older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 1744–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, H.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y.; Tian, X.; Qiao, X.; Liu, N.; Dong, L. Prevalence, factors, and health impacts of chronic pain among community-dwelling older adults in china. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2019, 20, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.V.; Guralnik, J.M.; Dansie, E.J.; Turk, D.C. Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the united states: Findings from the 2011 national health and aging trends study. PAIN® 2013, 154, 2649–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, E.; Peat, G.; Harris, L.; Wilkie, R.; Croft, P.R. The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: Cross-sectional findings from the north staffordshire osteoarthritis project (norstop). Pain 2004, 110, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, S.; Kobayashi, F.; Nishihara, M.; Arai, Y.-C.P.; Ikemoto, T.; Kawai, T.; Inoue, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Ushida, T. Chronic pain in the japanese community—Prevalence, characteristics and impact on quality of life. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, L.; Donovan, C.; Gao, Y.; Ali, G.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, T.; Shan, G.; Sun, W. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic body pain in china: A national study. Springerplus 2016, 5, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ya-yang, L. Pain and its influencing factors in the disabled elderly in china. Chin. J. Pain Med. 2024, 30, 678–685. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Chen, J.; Johannesson, M.; Kind, P.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Burström, K. Regional differences in health status in china: Population health-related quality of life results from the national health services survey 2008. Health Place 2011, 17, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, K.; Li, R.; Xing, D.; Chen, Y. The prevalence and economic burden of pain on middle-aged and elderly Chinese people: Results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Li, D.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Prieto-Alhambra, D.; Zheng, X. Chronic disease in china: Geographic and socioeconomic determinants among persons aged 60 and older. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 206–212.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, X.; Feng, Z.; Qiu, F.; Xin, G.; Liu, J.; Nie, F.; Jin, X.; Liu, Y. A survey of chronic pain in china. Libyan J. Med. 2020, 15, 1730550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wranker, L.S.; Rennemark, M.; Berglund, J. Pain among older adults from a gender perspective: Findings from the swedish national study on aging and care (snac-blekinge). Scand. J. Public Health 2016, 44, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullachery, P.H.; Lima-Costa, M.F.; de Loyola Filho, A.I. Prevalence of pain and use of prescription opioids among older adults: Results from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSI-Brazil). Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2023, 20, 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.K.; Ambade, M.; Upadhyay, A.K.; Mishra, R.S.; Pedgaonkar, S.P.; Kampfen, F.; O’DOnnell, O.; Maurer, J. Prevalence of pain and its treatment among older adults in india: A nationally representative population-based study. Pain 2023, 164, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Dawson, J.E.; Brooks, M.; Khan, J.S.; Telusca, N. Disparities in pain management. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2023, 41, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Peat, G.; Jordan, K.; Yu, D.; Wilkie, R. Where does it hurt? Small area estimates and inequality in the prevalence of chronic pain. Eur. J. Pain 2023, 27, 1177–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macgregor, C.; Walumbe, J.; Tulle, E.; Seenan, C.; Blane, D.N. Intersectionality as a theoretical framework for researching health inequities in chronic pain. Br. J. Pain 2023, 17, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.B.; Liu, E.C.; Bully, M.A.; Johnson, M.E.; Smith, T.J. Overcoming barriers: A comprehensive review of chronic pain management and accessibility challenges in rural America. Healthcare 2024, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Areias, A.C.; Molinos, M.; Moulder, R.G.; Janela, D.; Scheer, J.K.; Bento, V.; Yanamadala, V.; Cohen, S.P.; Correia, F.D.; Costa, F. The potential of a multimodal digital care program in addressing healthcare inequities in musculoskeletal pain management. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Wang, X. Associations of multimorbidity with body pain, sleep duration, and depression among middle-aged and older adults in china. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2024, 22, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leadley, R.; Armstrong, N.; Lee, Y.; Allen, A.; Kleijnen, J. Chronic diseases in the european union: The prevalence and health cost implications of chronic pain. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2012, 26, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sara, R.; Zimmer, Z. Pain and self-assessed health: Does the association vary by age? Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 130, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, M.H.; Mapel, D.W.; Hartry, A.; Von Worley, A.; Thomson, H. Chronic pain and pain medication use in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A cross-sectional study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2013, 10, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Group | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 21,346 (100) | |

| Pain | None | 9280 (43.5) |

| Yes | 12,066 (56.5) | |

| Pain degree | Mild | 2577 (21.4) |

| Moderate | 5877 (48.7) | |

| Severe | 3438 (28.5) | |

| Missing | 174 (1.4) | |

| Age group | 60–64 | 7277 (34.1) |

| 65–69 | 4795 (22.5) | |

| 70–74 | 3296 (15.4) | |

| 75–79 | 2850 (13.4) | |

| ≥80 | 3128 (14.7) | |

| Gender | Female | 11,042 (51.7) |

| Male | 10,304 (48.3) | |

| Urbanization | Urban | 11,162 (52.3) |

| Rural | 10,184 (47.7) | |

| Ethnicity | Han | 20,036 (93.9) |

| Ethnic minorities | 1294 (6.1) | |

| Missing | 16 (0.1) | |

| Region | Eastern | 8973 (42.0) |

| Central | 6529 (30.6) | |

| Western | 5844 (27.4) | |

| Total household income quintile | 1 | 4342 (20.3) |

| 2 | 4804 (22.5) | |

| 3 | 3692 (17.3) | |

| 4 | 4475 (21.0) | |

| 5 | 3829 (17.9) | |

| Missing | 204 (1.0) | |

| Education attainment | Illiteracy | 6069 (28.4) |

| Primary school | 8863 (41.5) | |

| Junior high school and above | 6357 (29.8) | |

| Missing | 57 (0.3) | |

| Basic medical insurance for urban employees | None | 16,791 (78.7) |

| Yes | 4498 (21.1) | |

| Missing | 57 (0.3) | |

| Smoking | Never smoking | 14,023 (65.7) |

| Already quit smoking | 2225 (10.4) | |

| Occasional smoking | 1061 (5.0) | |

| Regular smoking | 3938 (18.4) | |

| Missing | 99 (0.5) | |

| Drinking | <1 times a week | 18,159 (85.1) |

| 1~2 times a week | 825 (3.9) | |

| ≥3 times a week | 1918 (9.0) | |

| Frequent intoxication | 274 (1.3) | |

| Missing | 170 (0.8) | |

| Exercise times a week | Never exercise | 10,629 (49.8) |

| ≤2 times | 3482 (16.3) | |

| 3~5 times | 2471 (11.6) | |

| ≥6 times | 4720 (22.1) | |

| Missing | 44 (0.2) | |

| Cataracts | None | 18,006 (84.5) |

| Yes | 3305 (15.5) | |

| Hypertension | None | 13,351 (62.6) |

| Yes | 7960 (37.4) | |

| Diabetes | None | 19,464 (91.3) |

| Yes | 1847 (8.7) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | None | 15,933 (74.8) |

| Yes | 5378 (25.2) | |

| Stomach disease | None | 17,105 (80.3) |

| Yes | 4206 (19.7) | |

| Arthritis | None | 11,318 (53.1) |

| Yes | 9993 (46.9) | |

| Chronic lung disease | None | 19,060 (89.4) |

| Yes | 2251 (10.6) | |

| Asthma | None | 20,150 (94.6) |

| Yes | 1161 (5.4) | |

| Cancer | None | 21,065 (98.8) |

| Yes | 246 (1.2) | |

| Reproductive disease | None | 20,602 (96.7) |

| Yes | 709 (3.3) | |

| Number of diseases | No disease | 3795 (17.8) |

| Single disease | 6729 (31.5) | |

| Double diseases | 5482 (25.7) | |

| Multimorbidity | 5305 (24.9) | |

| Missing | 35 (0.2) |

| Category | Group | N (%) | χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 60–64 | 3810 (52.36) | 105.18 | <0.001 |

| 65–69 | 2672 (55.72) | |||

| 70–74 | 1973 (59.86) | |||

| 75–79 | 1703 (59.75) | |||

| 80+ | 1908 (61.00) | |||

| Gender | Female | 6886 (62.36) | 317.05 | <0.001 |

| Male | 5180 (50.27) | |||

| Urbanization | Urban | 5826 (52.19) | 178.76 | <0.001 |

| Rural | 6240 (61.27) | |||

| Ethnicity | Han | 11,278 (56.29) | ||

| Ethnic minorities | 781 (60.36) | |||

| Region | Eastern | 4574 (50.98) | 235.37 | <0.001 |

| Central | 3776 (57.83) | |||

| Western | 3716 (63.59) | |||

| Total household income quintile | 1 | 2759 (63.54) | 294.48 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 2886 (60.07) | |||

| 3 | 2181 (59.07) | |||

| 4 | 2329 (52.04) | |||

| 5 | 1806 (47.17) | |||

| Education attainment | Illiteracy | 3950 (65.08) | 452.76 | <0.001 |

| Primary school | 5139 (57.98) | |||

| Junior high school and above | 2951 (46.42) | |||

| Basic medical insurance for urban employees | None | 9959 (59.31) | 249.94 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2076 (46.15) | |||

| Smoking | Never smoking | 8131 (57.98) | 55.75 | <0.001 |

| Already quit smoking | 1275 (57.3) | |||

| Occasional smoking | 530 (49.95) | |||

| Regular smoking | 2072 (52.62) | |||

| Drinking | <1 times a week | 10,478 (57.7) | 78.75 | <0.001 |

| 1~2 times a week | 372 (45.09) | |||

| ≥3 times a week | 979 (51.04) | |||

| Frequent intoxication | 146 (53.28) | |||

| Exercise times a week | Never exercise | 6534 (61.47) | 225.07 | <0.001 |

| ≤2 times | 1867 (53.62) | |||

| 3~5 times | 1308 (52.93) | |||

| ≥6 times | 2337 (49.51) | |||

| Cataracts | None | 9783 (54.33) | 236.19 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 2272 (68.74) | |||

| Hypertension | None | 7192 (53.87) | 105.93 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 4863 (61.09) | |||

| Diabetes | None | 10,932 (56.17) | 14.72 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1123 (60.80) | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | None | 8247 (51.76) | 593.69 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 3808 (70.81) | |||

| Stomach disease | None | 8955 (52.35) | 626.57 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 3100 (73.70) | |||

| Arthritis | None | 4451 (39.33) | 2919.38 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 7604 (76.09) | |||

| Chronic lung disease | None | 10,413 (54.63) | 274.88 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1642 (72.95) | |||

| Asthma | None | 11,173 (55.45) | 188.13 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 882 (75.97) | |||

| Cancer | None | 11,869 (56.34) | 36.75 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 186 (75.61) | |||

| Reproductive disease | None | 11,529 (55.96) | 92.70 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 526 (74.19) | |||

| Number of diseases | No disease | 927 (24.43) | 2948.04 | <0.001 |

| Single disease | 3389 (50.36) | |||

| Double diseases | 3538 (64.54) | |||

| Multimorbidity | 4201 (79.19) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, G.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jia, Z.; Ning, X.; Wang, C. Prevalence, Geographic Variations, and Determinants of Pain Among Older Adults in China: Findings from the National Urban and Rural Elderly Population (UREP) Survey. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212720

Yan G, Wu Y, Zhang H, Jia Z, Ning X, Wang C. Prevalence, Geographic Variations, and Determinants of Pain Among Older Adults in China: Findings from the National Urban and Rural Elderly Population (UREP) Survey. Healthcare. 2025; 13(21):2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212720

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Ge, Yutong Wu, Hui Zhang, Zhimeng Jia, Xiaohong Ning, and Chen Wang. 2025. "Prevalence, Geographic Variations, and Determinants of Pain Among Older Adults in China: Findings from the National Urban and Rural Elderly Population (UREP) Survey" Healthcare 13, no. 21: 2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212720

APA StyleYan, G., Wu, Y., Zhang, H., Jia, Z., Ning, X., & Wang, C. (2025). Prevalence, Geographic Variations, and Determinants of Pain Among Older Adults in China: Findings from the National Urban and Rural Elderly Population (UREP) Survey. Healthcare, 13(21), 2720. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212720