The Effects of the Schroth Method on the Cobb Angle, Angle of Trunk Rotation, Pulmonary Function, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Narrative Review

Abstract

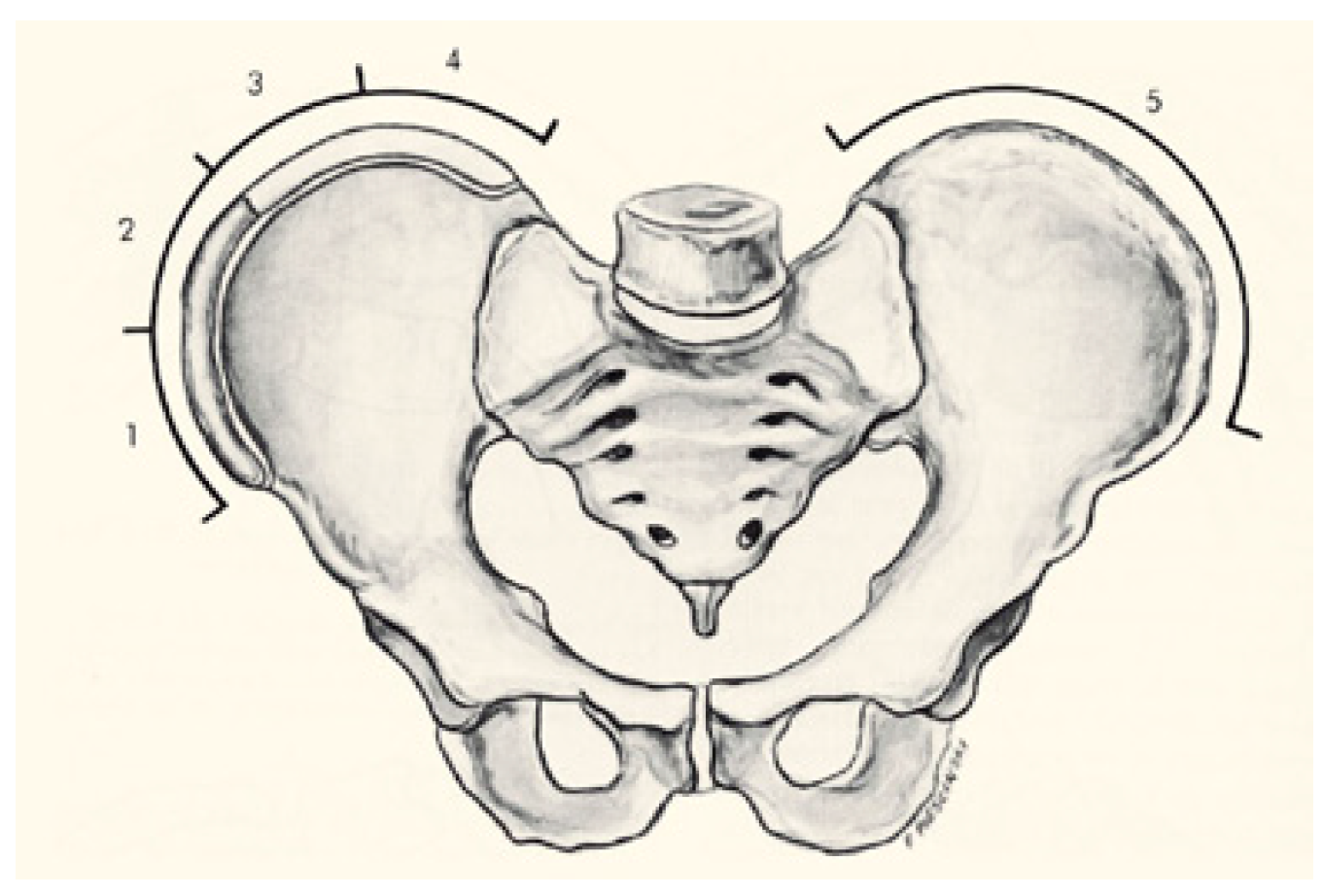

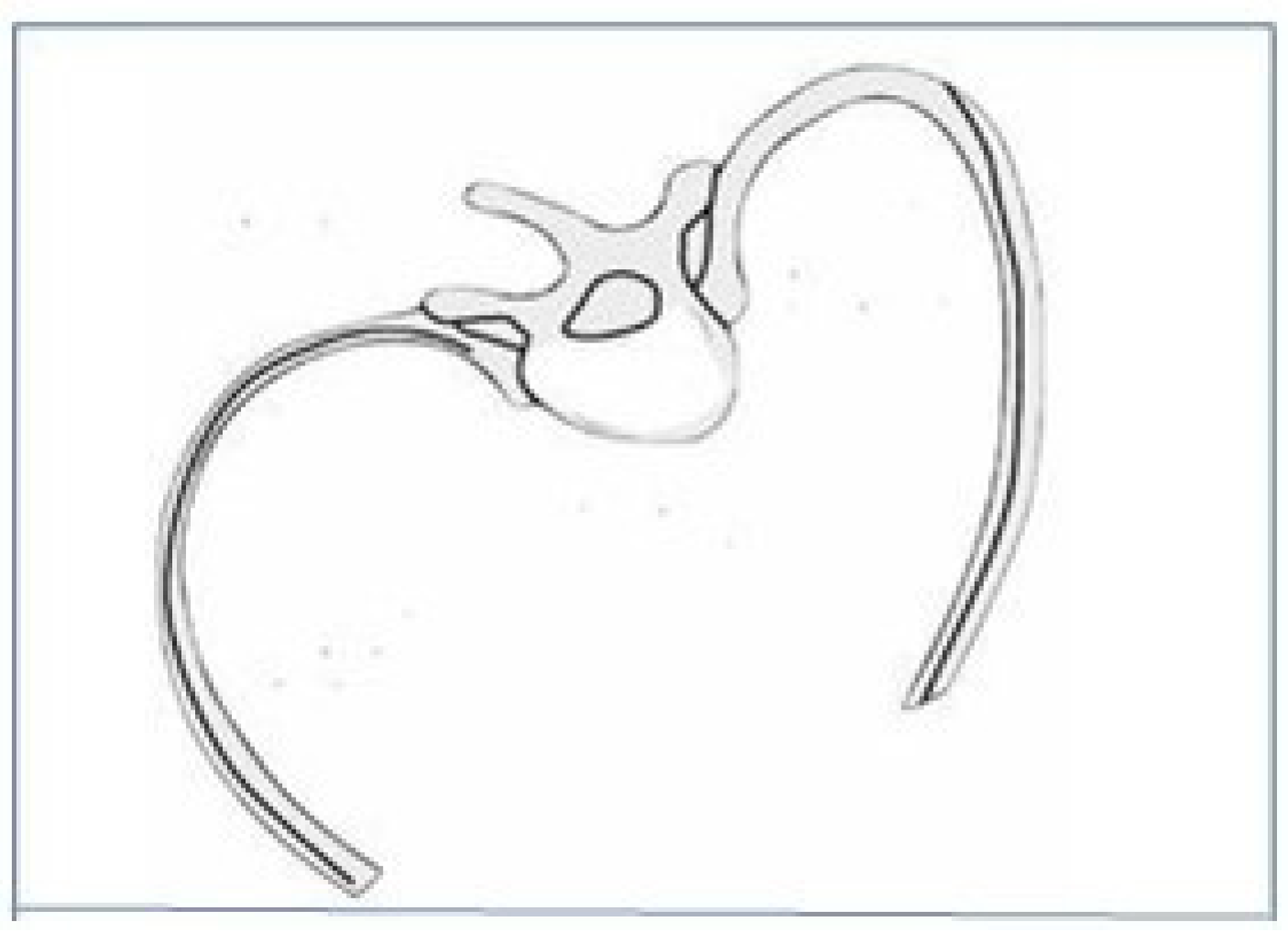

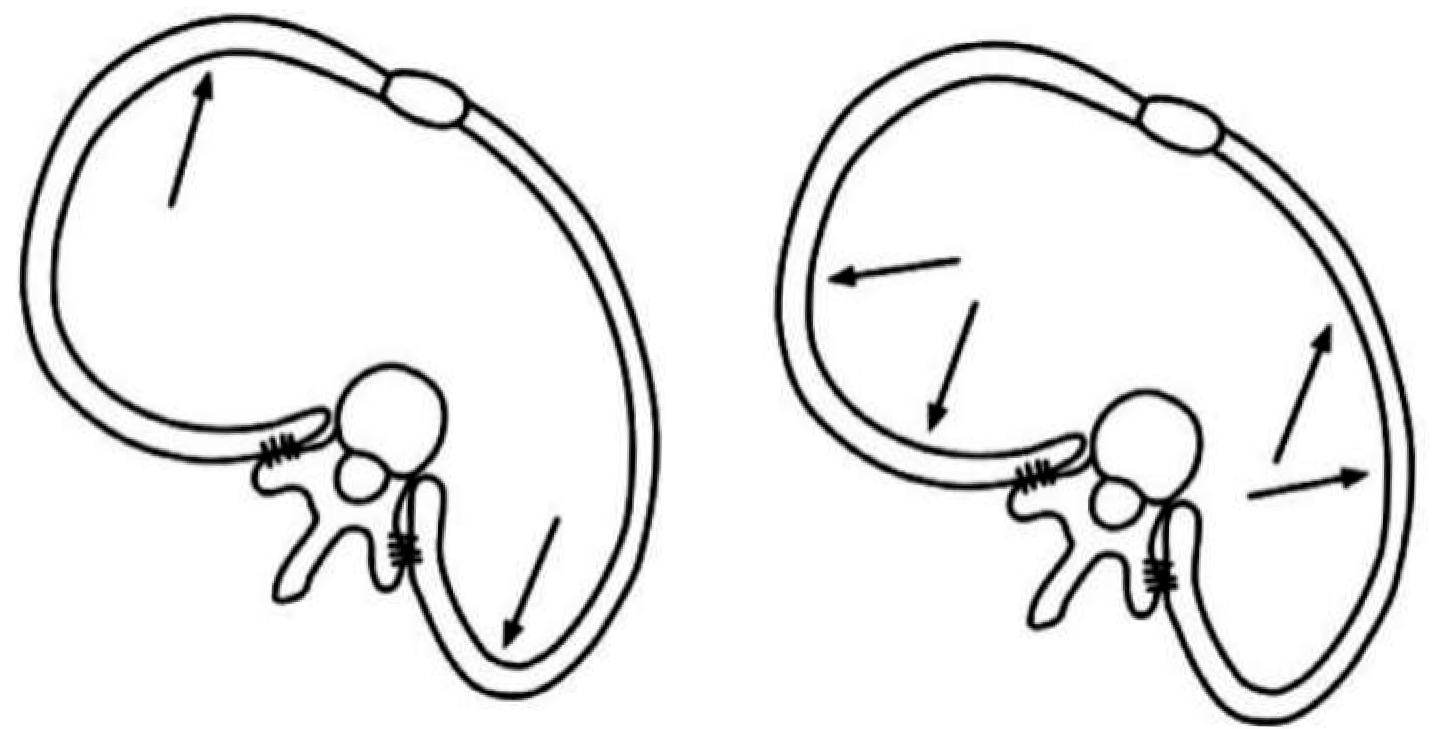

1. Introduction

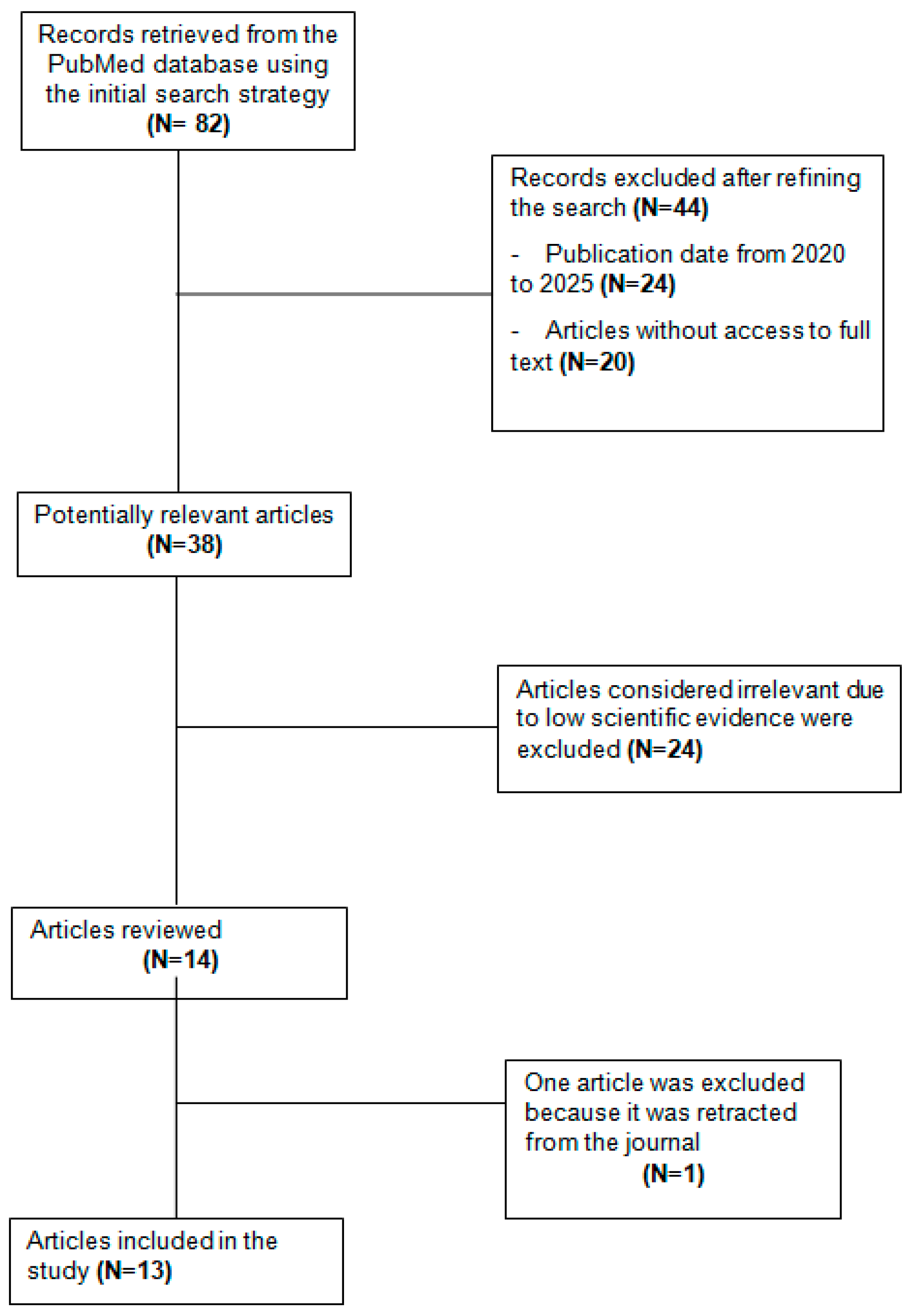

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIS | Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis |

| ATR | Angle of Trunk Rotation |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| FVC | Forced Vital Capacity |

| TPLV | Total Lung Volume |

| SRS-22 | Scoliosis Research Society-22 |

| SEAS | Scientific Exercise Approach for Scoliosis |

| BSPTS | Barcelona School of Physical Therapy for Scoliosis |

| FITS | Functional Independent Treatment for Scoliosis |

| PNF | Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation |

References

- Peng, Y.; Wang, S.R.; Qiu, G.X.; Zhang, J.G.; Zhuang, Q.Y. Research progress on the etiology and pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, R.P.; Sin, A.H. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2009, 40, 527–536. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.Y.; Saigal, G.; Palasis, S.; Booth, T.N.; Hayes, L.L.; Iyer, R.S.; Kadom, N.; Kulkarni, A.V.; Milla, S.S.; Myseros, J.S.; et al. ACR appropriateness criteria® scoliosis-child. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2019, 16, S244–S251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinnah, A.H.; Lynch, K.A.; Wood, T.R.; Hughes, M.S. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Advances in Diagnosis and Management. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2025, 18, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez García de Quesada, L.I.; Núñez Giralda, A. Idiopathic scoliosis. Pediatr. Aten Primaria 2011, 13, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- de Adolescencia, C.N.; de Diagnóstico por Imágenes, C.; de Ortopedia y Traumatología Infantil, S.A.; de Patología de la Columna Vertebral, S.A. Consenso de escoliosis idiopática del adolescente. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2016, 114, 585–594. [Google Scholar]

- Lenz, M.; Oikonomidis, S.; Harland, A.; Fürnstahl, P.; Farshad, M.; Bredow, J.; Eysel, P.; Scheyerer, M.J. Scoliosis and Prognosis—A systematic review regarding patient-specific and radiological predictive factors for curve progression. Eur. Spine J. 2021, 30, 1813–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelliaume, A.; Pfirrmann, C.; Alhada, T.; Sales de Gauzy, J. Non-operative treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2025, 111, 104078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufvenberg, M.; Charalampidis, A.; Diarbakerli, E.; Öberg, B.; Tropp, H.; Ahl, A.A.; Wezenberg, D.; Hedevik, H.; Möller, H.; Gerdhem, P.; et al. Prognostic model development for risk of curve progression in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A prospective cohort study of 127 patients. Acta Orthop. 2024, 95, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, K.; Singh, M.; McDermott, J.R.; Gregorczyk, J.A.; Balmaceno-Criss, M.; Daher, M.; McDonald, C.L.; Diebo, B.G.; Daniels, A.H. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in adulthood. EFORT Open Rev. 2024, 9, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, M.M.P.; Negrini, S.; Di Felice, F.; Cheung, J.P.Y.; Donzelli, S.; Zaina, F.; Samartzis, D.; Cheung, E.T.C.; Wong, A.Y.L. Is impaired lung function related to spinal deformities in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis-SOSORT 2019 award paper. Eur. Spine J. 2023, 32, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te Hennepe, N.; Faraj, S.S.A.; Pouw, M.H.; de Kleuver, M.; van Hooff, M.L. Pulmonary symptoms in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic review to identify patient-reported and clinical measurement instruments. Eur. Spine J. 2022, 31, 1916–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantoja, T.S.; Chamorro, L.M. Scoliosis in children and adolescents. Rev. Médica Clin. Las Condes 2015, 26, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwahi, V.; Galina, J.; Atlas, A.; Gecelter, R.; Hasan, S.; Amaral, T.D.; Maguire, K.; Lo, Y.; Kalantre, S. Scoliosis Surgery Normalizes Cardiac Function in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Patients. Spine 2021, 46, E1161–E1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feddema, T.J.; Miller, F.Z.A.; Erickson, M.A.; Garg, S. Patient-Reported Mental Health and Quality of Life in Pediatric Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Patients. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. Glob. Res. Rev. 2025, 9, e24.00253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükturan, Ö.; Kaya, M.H.; Alkan, H.; Büyükturan, B.; Erbahçeci, F. Comparison of the efficacy of Schroth and Lyon exercise treatment techniques in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A randomized controlled, assessor and statistician blinded study. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2024, 72, 102952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, M.; Coetzee, W.; du Plessis, L.Z.; Geldenhuys, L.; Joubert, F.; Myburgh, E.; van Rooyen, C.; Vermeulen, N. The effectiveness of Schroth exercises in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. S. Afr. J. Physiother. 2019, 75, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moramarco, K.; Borysov, M. A modern historical perspective on Schroth scoliosis rehabilitation and bracing techniques for idiopathic scoliosis. Open Orthop. J. 2017, 11, 1452–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijević, V.; Rašković, B.; Popović, M.; Viduka, D.; Nikolić, S.; Drid, P.; Obradović, B. Treatment of idiopathic scoliosis with conservative methods based on exercises: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 149224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaman, H.; Bek, N.; Kaya, M.H.; Büyükturan, B.; Yetiş, M.; Büyükturan, Ö. The effectiveness of two different exercise approaches in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A single-blind, randomized-controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, R.A.; Yousef, A.M. Impact of Schroth three-dimensional vs. proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation techniques in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A randomized controlled study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 7717–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahim, T.; Virsanikar, S.; Mangharamani, D.; Khan, S.N.; Mhase, S.; Umate, L. Physiotherapy Interventions for Preventing Spinal Curve Progression in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e30314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceballos-Laita, L.; Carrasco-Uribarren, A.; Cabanillas-Barea, S.; Pérez-Guillén, S.; Pardos-Aguilella, P.; Jiménez Del Barrio, S. The effectiveness of Schroth method in Cobb angle, quality of life and trunk rotation angle in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 59, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, S.; Whibley, D.; Somers, E.C. Schroth Physiotherapeutic Scoliosis-Specific Exercise (PSSE) Trials-Systematic Review of Methods and Recommendations for Future Research. Children 2023, 10, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Q. The effect of an exercise intervention on adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A network meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Acharya, V.; Schreiber, S.; Parent, E.C.; Westover, L. Effect of adding Schroth physiotherapeutic scoliosis specific exercises to standard care in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis on posture assessed using surface topography: A secondary analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT). PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaledi, A.; Minoonejad, H.; Akoochakian, M.; Gheitasi, M. Core Stabilization Exercises vs. Schroth’s Three Dimensional Exercises to Treat Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Systematic Review. Iran. J. Public Health 2024, 53, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, J.; Li, H. Effects of Schroth 3D Exercise on Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Children 2024, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chai, T.; Weng, H.; Liu, Y. Pelvic rotation correction combined with Schroth exercises for pelvic and spinal deformities in mild adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrkousis, A.; Iakovidis, P.; Chatziprodromidou, I.P.; Lytras, D.; Kasimis, K.; Apostolou, T.; Koutras, G. Effects of a long-term supervised Schroth exercise program on the severity of scoliosis and quality of life in individuals with adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A randomized clinical trial study. Medicina 2024, 60, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Li, G.; Guo, X. Comparative efficacy of six types of scoliosis-specific exercises on adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufvenberg, M.; Charalampidis, A.; Diarbakerli, E.; Öberg, B.; Tropp, H.; Ahl, A.A.; Möller, H.; Gerdhem, P.; Abbott, A.; CONTRAIS Study Group. Trunk rotation, spinal deformity and appearance, health-related quality of life, and treatment adherence: Secondary outcomes in a randomized controlled trial on conservative treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliadis, E.; Grivas, T.B. Quality of life after conservative treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2008, 135, 409–413. [Google Scholar]

| STUDY | OBJECTIVE | METHODS | CONCLUSION |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kocaman H, et al., 2021 [20] | To evaluate effectiveness of Schroth method versus Core stabilization exercises. | RCT. Cobb angle (10–25°). Group Schroth and Group of Core exercises. Variables: Cobb angle, ATR, esthetic, joint, muscle balance, and health-related quality of life. | Schroth exercises were effective in improving Cobb angle, ATR, esthetic, joint and muscle balance, and health-related quality of life (p < 0.05). |

| Mohamed RA, et al., 2021 [21] | To assess the effectiveness of Schroth versus PFN exercises. | RCT. Cobb angle (10–25°). Risser ≤ 3 Group Schroth and Group of PFN. Variables: Cobb angle, ATR, plantar pressure, and pulmonary capacity. | Schroth exercises were more effective in reducing Cobb angle, ATR, plantar pressure, and pulmonary capacity (p < 0.05). |

| Fahim T, et al., 2022 [22] | To analyze the effectiveness of different physiotherapy interventions. | Systematic review. Schroth method, SEAS and core stabilization exercises, orthosis, and combination of Cobb angle. | The Schroth method showed a greater reduction in Cobb angle and this reduction was greater when combined with orthosis (p < 0.05). |

| Ceballos-Laita L, et al., 2023 [23] | To study the effectiveness of Schroth method versus other conservative treatments or no intervention. | Systematic review and meta-analysis Schroth method alone versus other conservative treatments or no intervention on Cobb angle, health-related quality of life, and ATR. | The Schroth method alone was effective in the short term in reducing Cobb angle, ATR, and improving quality of life (p < 0.05). |

| Schreiber S, et al., 2023 [24] | To review the scientific evidence of Schroth method. | Systematic review. Cobb angle (10–45°). The quality of published studies was evaluated. | Improvement of quality of life but no significant reduction in Cobb angle (p < 0.05). Methodological quality limits their validity. |

| Chen Y, et al., 2023 [25] | To evaluate the effect of exercises versus conventional therapies on Cobb angle. | Systematic review and meta-analysis. Schroth, core stabilization, yoga, and suspension exercises versus conventional therapies. | The exercises were more effective in reducing Cobb angle than conventional therapies, without differences between different exercises (p < 0.001). |

| Mohamed N, et al., 2024 [26] | To compare Schroth method associated with standard treatment versus standard treatment alone. | RCT. Cobb angle (10–45°), Risser ≤ 3 Group Schroth + standard treatment and Group standard treatment alone on ATR | The combination of Schroth exercises to standard treatment showed a reduction in ATR (p < 0.05). |

| Khaledi A, et al., 2024 [27] | To evaluate the available evidence on the effectiveness of Schroth exercises versus core stabilization exercises. | Systematic review. Schroth versus core stabilization on Cobb angle. | No statistically significant differences were found between the two methods in terms of Cobb angle reduction (p > 0.05). |

| Chen C, et al., 2024 [28] | To assess the evidence on effectiveness of Schroth exercises versus conventional treatment. | Systematic review and meta-analysis. Variables: Cobb angle, ATR, muscle strength, and health-related quality of life | The Schroth method was more effective in reducing Cobb angle, ATR, increasing muscle strength, and improving health-related quality of life (p < 0.001). |

| Zhang Y, et al., 2024 [29] | To evaluate the effectiveness of PNF-based pelvic rotation correction combined with Schroth exercises versus Schroth exercises alone. | RCT. Group Schroth exercises + PNF and Group Schroth exercises alone. Variables: pelvic asymmetry index, Cobb angle, ATR, and health-related quality of life. | The combination of pelvic rotation correction with Schroth exercises was more effective than Schroth exercises alone in improving spinal and pelvic deformities. No significant differences in ATR and Cobb angle (p > 0.05). |

| Kyrkousis A, et al., 2024 [30] | To evaluate the effectiveness of Schroth exercises and orthoses versus orthoses alone. | RCT. Group Schroth exercises + brace and Group brace. Variables: Cobb angle, ATR, and health-related quality of life. | Schroth exercises and orthopedic treatment demonstrated a reduction in Cobb angle, ATR, and health-related quality of life (p < 0.001). |

| Wang Z, et al., 2024 [31] | To evaluate the evidence in the literature on effectiveness of different exercises on spinal deformity and health-related quality of life. | Systematic review and meta-analysis. Specific exercises compared to routine care, bracing, and general exercises. Variables: Cobb angle, ATR, and health-related quality of life. | Schroth method was effective in the short and long term in reducing Cobb angle and improving quality of life. Active self-correction showed the best short-term results (p < 0.05). |

| Dimitrijević V, et al., 2024 [19] | To review the evidence of the effect of different exercises on AIS. | Systematic review and meta-analysis. The effect of different types of exercises was evaluated. Variables: Cobb angle, ATR, lung function, and health-related quality of life. | Schroth method had positive effect on reduction in Cobb angle, and improvement of health-related quality of life and FEV1 (p < 0.05). No significant differences were found in ATR and FVC (p = 0.06). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Jiménez, A.B.; Gámez-Centeno, E.; Muñoz-Paz, J.; Muñoz-Alcaraz, M.N.; Mayordomo-Riera, F.J. The Effects of the Schroth Method on the Cobb Angle, Angle of Trunk Rotation, Pulmonary Function, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2631. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202631

Jiménez-Jiménez AB, Gámez-Centeno E, Muñoz-Paz J, Muñoz-Alcaraz MN, Mayordomo-Riera FJ. The Effects of the Schroth Method on the Cobb Angle, Angle of Trunk Rotation, Pulmonary Function, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Narrative Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(20):2631. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202631

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Jiménez, Ana Belén, Elena Gámez-Centeno, Javier Muñoz-Paz, María Nieves Muñoz-Alcaraz, and Fernando Jesús Mayordomo-Riera. 2025. "The Effects of the Schroth Method on the Cobb Angle, Angle of Trunk Rotation, Pulmonary Function, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Narrative Review" Healthcare 13, no. 20: 2631. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202631

APA StyleJiménez-Jiménez, A. B., Gámez-Centeno, E., Muñoz-Paz, J., Muñoz-Alcaraz, M. N., & Mayordomo-Riera, F. J. (2025). The Effects of the Schroth Method on the Cobb Angle, Angle of Trunk Rotation, Pulmonary Function, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Narrative Review. Healthcare, 13(20), 2631. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202631