Women’s Attitudes Toward Fertility and Childbearing: A National Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Data Collection

- (a)

- Sociodemographic characteristics: age, current residency, marital status, education level, occupation status, and income.

- (b)

- Medical and psychiatric history: diagnosis of medical conditions, diagnosis of psychiatric conditions, infertility, and contraceptive methods used.

- (c)

- Childbearing preference: sex and timing of having children.

- (d)

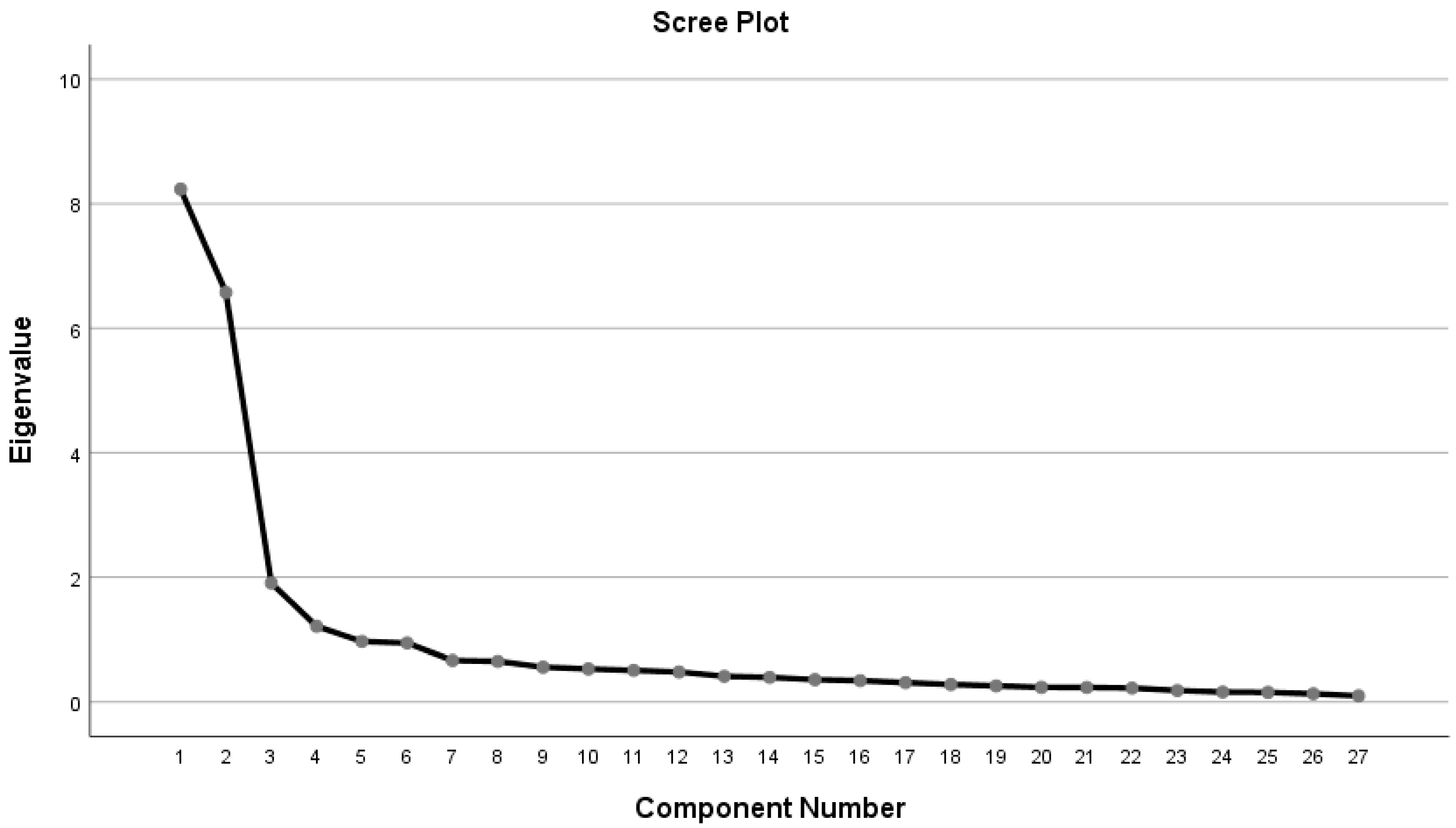

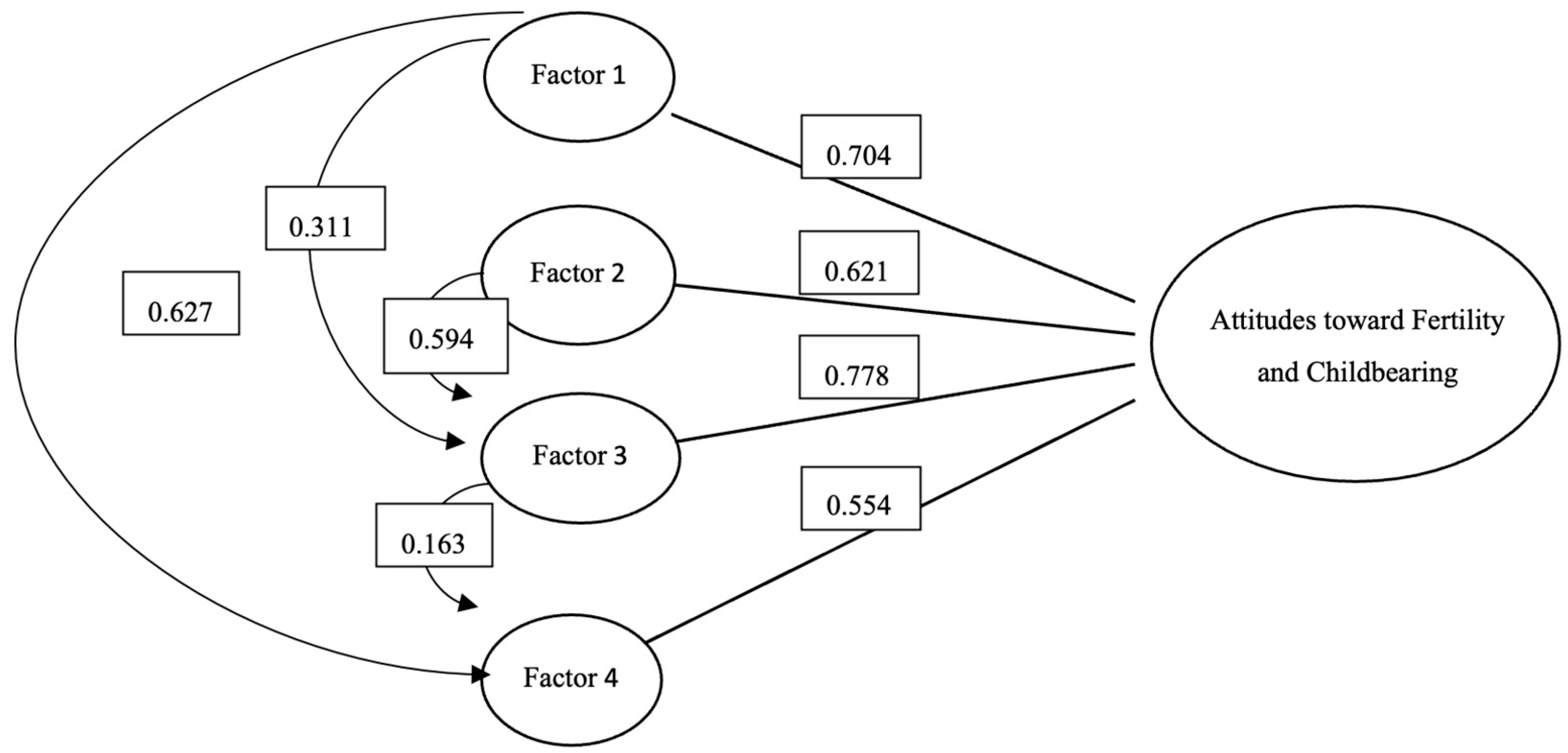

- Attitudes toward Fertility and Childbearing Scale (AFCS): This scale evaluates attitudes toward fertility and childbearing. It consists of 27 items (see Table 3), each rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (5 = highly agree, and 1 = highly disagree). The original and first version of AFCS measure the construct (women’s attitudes to fertility and childbearing) with the main three factors: (1) Importance of Fertility for the Future with nine items (1 to 9); (2) Childbearing as a Hindrance at Present with 12 items (10 to 21); and (3) Social Identity with six items (22 to 27). It was used in previous research in many languages [21,22,23,24]. The Arabic version of the AFCS was developed following standard forward–backward translation procedures. Two independent bilingual experts—one with a background in reproductive health and the other in psychology independently translated the original English scale into Arabic. A third bilingual expert, blinded to the original scale, performed the back-translation into English. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by a committee consisting of translators and two senior researchers to ensure conceptual equivalence, cultural appropriateness, and clarity. The pre-final version was then evaluated for content validity by a panel of five subject-matter experts (two reproductive health specialists, one psychiatrist, one sociologist, and one public health researcher). Each expert independently rated the relevance and clarity of each item using Davis’s method, calculating both item-level (I-CVI) and scale-level (S-CVI) Content Validity Index scores. Items with I-CVI values below 0.80 were revised accordingly. The final Arabic version of the AFCS was then pilot-tested on 250 Arabic-speaking women to confirm comprehension and assess its validity and reliability before its use in the main study. It demonstrated very good to excellent validity and reliability. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.833 to 0.934. The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) showed four emerging factors (eigenvalues > 1) using the Oblimin rotation method. The instrument has four factors, which were labeled as follows: (1) Importance of Fertility for the future with nine items (F1 to F9), (2) Childbearing as a Hindrance at Present with nine items (H1, H2, H4, H5, H6, H7, H8, H9, H10), (3) Childbearing preparation with six items (H3, H11, H12, S3, S4, S5) and (4) Female identity with three items (S1, S2, S6). Following the successful validation in the pilot phase, the main study was conducted using he larger sample (n = 2,172) to address the primary research questions regarding Saudi women’s attitude toward fertility and childbearing and their associations with sociodemographic, medical, and psychological factors.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pilot Study Results: Psychometric Validation of the Arabic AFCS (n = 250)

3.1.1. The Sociodemographic Characteristics and State of Health

3.1.2. Reliability

3.1.3. Validity

3.2. Main Study Results: Attitudes Toward Fertility and Childbearing (n = 2172)

- (1)

- Importance for the future

- (2)

- Hindrance at present

- (3)

- Childbearing preparation

- (4)

- Female identity

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khadivzadeh, T.; Rahmanian, S.A.; Esmaily, H. Young Women and Men’s Attitude towards Childbearing. J. Midwifery Reprod. Health 2018, 6, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, B.B.; Sendekie, A.K.; Ayele, M.; Lake, E.S.; Wodaynew, T.; Tilahun, B.D.; Azmeraw, M.; Habtie, T.E.; Kassa, M.; Munie, M.A.; et al. Mapping fertility rates at national, sub-national, and local levels in Ethiopia between 2000 and 2019. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1363284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Haque, M.d.A. Role of women’s empowerment in determining fertility and reproductive health in Bangladesh: A systematic literature review. AJOG Glob. Rep. 2023, 3, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winckler, O. The fertility revolution of the Arab countries following the Arab Spring. Middle East Policy 2023, 30, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Open Data. World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Hashemzadeh, M.; Shariati, M.; Nazari, A.M.; Keramat, A. Childbearing intention and its associated factors: A systematic review. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2354–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, K.B.; Hayford, S.R.; Lang, V.W. Adolescent fertility attitudes and childbearing in early adulthood. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2018, 38, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, A.; Mills, T.A.; Lavender, T. Advanced maternal age: Delayed childbearing is rarely a conscious choice. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 49, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rackin, H.; Morgan, S.P. Prospective versus retrospective measurement of unwanted fertility: Strengths, weaknesses, and inconsistencies assessed for a cohort of US women. Demogr. Res. 2018, 39, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfarpour, M.; Kaviani, M.; Abdolahian, S.; Bonakchi, H.; Najmabadi Khadijeh, M.; Naghavi, M.; Khadivzadeh, T. The relationship between women’s attitude towards menopause and menopausal symptoms among postmenopausal women. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2015, 31, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.; Smith, C.; Shield, M. Women’s attitudes towards children and motherhood: A predictor of future childlessness? J. Soc. Incl. 2015, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.T.A.; Addo, K.M.; Findlay, H. Public health challenges and responses to the growing ageing populations. Public Health Chall. 2024, 3, e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, J.S. Ideational Influences on the Transition to Parenthood: Attitudes toward Childbearing and Competing Alternatives. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2001, 64, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderberg, M.; Lundgren, I.; Christensson, K.; Hildingsson, I. Attitudes toward fertility and childbearing scale: An assessment of a new instrument for women who are not yet mothers in Sweden. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tydén, T.; Svanberg, A.S.; Karlström, P.O.; Lihoff, L.; Lampic, C. Female university students’ attitudes to future motherhood and their understanding about fertility. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2006, 11, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, L.L.; Hegaard, H.K.; Andersen, A.N.; Bentzen, J.G. Attitudes towards motherhood and fertility awareness among 20–40-year-old female healthcare professionals. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2012, 17, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.J.; Jo, M. Attitudes towards Parenthood and Fertility Awareness in Female and Male University Students in South Korea. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2020, 26, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiser, B.; Mitchell, P.B.; Kasparian, N.A.; Strong, K.; Simpson, J.M.; Mireskandari, S.; Tabassum, L.; Schofield, P.R. Attitudes towards childbearing, causal attributions for bipolar disorder and psychological distress: A study of families with multiple cases of bipolar disorder. Psychol. Med. 2007, 37, 1601–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdridge, D.; Sheeran, P.; Connolly, K. Understanding the reasons for parenthood. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2005, 23, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaraj, S.; Aleraij, S.; Morad, S.; Alomar, N.; Al Rajih, H.; Alhussain, H.; Abushrai, F.; Al Thubaiti, A. Fertility awareness, intentions concerning childbearing, and attitudes toward parenthood among female health professions students in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Health Sci. 2019, 13, 34–39. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6512144/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Miyata, M.; Matsukawa, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Yokoyama, K.; Takeda, S. Psychometric Properties of Japanese Version of the Attitudes towards Fertility and Childbearing Scale (AFCS). Br. J. Med. Med. Res. 2017, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aşcı, Ö.; Gökdemir, F. Adaptation of attitudes toward fertility and childbearing scale to Turkish. Kocaeli Med. J. 2021, 10, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossakowska, K.; Söderberg, M. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the attitudes to fertility and childbearing scale (AFCS) in a sample of polish women. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 40, 3125–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.A. JMASM 48: The Pearson Product-Moment Correlation Coefficient and adjustment indices: The Fisher Approximate Unbiased Estimator and the Olkin-Pratt Adjustment (SPSS). J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2017, 16, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.M.X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Shafiabady, N.; Yan, W.; Gou, J.; Gide, E.; Zhang, S. An FSV analysis approach to verify the robustness of the triple-correlation analysis theoretical framework. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maskey, R.; Fei, J.; Nguyen, H.O. Use of exploratory factor analysis in maritime research. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2018, 34, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goretzko, D.; Bühner, M. Factor retention using machine learning with ordinal data. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 2022, 46, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helms, J.E.; Henze, K.T.; Sass, T.L.; Mifsud, V.A. Treating Cronbach’s Alpha Reliability coefficients as data in counseling research. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 630–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göral, S.; Özkan, S.; Sercekus, P.; Alataş, E. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Attitudes to Fer-Tility and Childbearing Scale (AFCS). Int. J. Assess. Tools Educ. 2021, 8, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Cronbach’s Alpha [95% CI] | r (ICC) | McDonald’s Omega [95% CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All AFCS items | 0.898 [0.867–0.929] | 0.882 excellent | 0.853 [0.827–0.879] | <0.01 * |

| Factor 1 (F1–F9) | 0.934 [0.919–0.949] | 0.925 excellent | 0.935 [0.922–0.947] | <0.01 * |

| Factor 2 (H1, H2, H4–H10) | 0.881 [0.856–0.906] | 0.870 excellent | 0.886 [0.865–0.907] | <0.01 * |

| Factor 3 (H3, H11, H12, S3–S5) | 0.875 [0.836–0.914] | 0.851 excellent | 0.870 [0.844–0.895] | <0.01 * |

| Factor 4 (S1, S2, S6) | 0.833 [0.787–0.879] | 0.832 excellent | 0.852 [0.822–0.882] | <0.01 * |

| Questions | r | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| (F1) I look forward to one day becoming a mother | 0.561 | <0.01 * |

| (F2) Having children is an essential part of life | 0.557 | <0.01 * |

| (F3) Having children will develop me as a person | 0.608 | <0.01 * |

| (F4) find it hard to imagine living a life without children | 0.427 | <0.01 * |

| (F5) I can imagine being pregnant and giving birth | 0.577 | <0.01 * |

| (F6) Having a child is a way for me to add new elements in life | 0.595 | <0.01 * |

| (F7) I talk to my friends about having children in the future | 0.484 | <0.01 * |

| (F8) It is important for me to be fertile | 0.696 | <0.01 * |

| (F9) It is important for me to be able to get pregnant anytime | 0.663 | <0.01 * |

| (H1) Having children would limit my life right now | 0.475 | <0.01 * |

| (H2) An unplanned pregnancy would hinder me in my current life | 0.449 | <0.01 * |

| (H3) Childbearing does not fit into my life right now | 0.443 | <0.01 * |

| (H4) Taking responsibility for a child does not fit into my current life | 0.421 | <0.01 * |

| (H5) Having children would limit my leisure time activities | 0.500 | <0.01 * |

| (H6) I do not want to take responsibility as a mother now | 0.409 | <0.01 * |

| (H7) Having children would limit my career | 0.431 | <0.01 * |

| (H8) Being a mother would take too much of my own time | 0.536 | <0.01 * |

| (H9) Having children would limit my study opportunities | 0.462 | <0.01 * |

| (H10) Having children would limit socializing with my friends | 0.327 | <0.01 * |

| (H11) It is important for me to choose when to get pregnant | 0.603 | <0.01 * |

| (H12) It is important for me to have my own stable economy when I have children | 0.599 | <0.01 * |

| (S1) My fertility makes me feel communion with other women | 0.449 | <0.01 * |

| (S2) Being fertile is important for my identity as a woman | 0.497 | <0.01 * |

| (S3) It is important to me that the child is born in a nuclear family, i.e., mother, father, children | 0.688 | <0.01 * |

| (S4) When I have children, my life must be prepared for living with children | 0.702 | <0.01 * |

| (S5) It is important for me to have a stable relationship when I have children | 0.699 | <0.01 * |

| (S6) Becoming a mother is important for my identity as a woman | 0.492 | <0.01 * |

| Items | Factor Number * | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Importance for Future) | 2 (Hindrance at Present) | 3 (Childbearing Preparation) | 4 (Female Identity) | |||||

| Pattern Coefficients | Structure Coefficients | Pattern Coefficients | Structure Coefficients | Pattern Coefficients | Structure Coefficients | Pattern Coefficients | Structure Coefficients | |

| (F1) I look forward to one day becoming a mother | 0.831 | 0.844 | −0.017 | −0.069 | −0.078 | −0.202 | 0.000 | 0.357 |

| (F2) Having children is an essential part of life | 0.785 | 0.840 | −0.017 | −0.078 | −0.034 | −0.163 | 0.114 | 0.446 |

| (F3) Having children will develop me as a person | 0.643 | 0.710 | −0.025 | 0.022 | −0.280 | −0.376 | 0.048 | 0.349 |

| (F4) find it hard to imagine living a life without children | 0.753 | 0.784 | 0.004 | −0.130 | 0.168 | 0.033 | 0.137 | 0.435 |

| (F5) I can imagine being pregnant and giving birth | 0.778 | 0.801 | 0.036 | −0.008 | −0.082 | −0.222 | 0.032 | 0.369 |

| (F6) Having a child is a way for me to add new elements in life | 0.669 | 0.802 | −0.056 | 0.069 | −0.111 | −0.224 | 0.261 | 0.556 |

| (F7) I talk to my friends about having children in the future | 0.716 | 0.753 | 0.017 | −0.065 | 0.039 | −0.091 | 0.105 | 0.402 |

| (F8) It is important for me to be fertile | 0.750 | 0.811 | 0.099 | 0.103 | −0.192 | −0.359 | 0.096 | 0.437 |

| (F9) It is important for me to be able to get pregnant anytime | 0.768 | 0.788 | 0.146 | 0.127 | −0.144 | −0.324 | 0.028 | 0.373 |

| (H1) Having children would limit my life right now | 0.277 | 0.245 | 0.448 | 0.438 | −0.046 | −0.256 | 0.014 | 0.153 |

| (H2) An unplanned pregnancy would hinder me in my current life | −0.092 | −0.126 | 0.476 | 0.630 | −0.386 | −0.543 | −0.118 | −0.093 |

| (H4) Taking responsibility for a child does not fit into my current life | −0.426 | −0.314 | 0.416 | 0.642 | −0.454 | −0.571 | 0.196 | 0.086 |

| (H5) Having children would limit my leisure time activities | −0.062 | −0.081 | 0.592 | 0.704 | −0.275 | −0.494 | −0.008 | 0.021 |

| (H6) I do not want to take responsibility as a mother now | −0.386 | −0.340 | 0.550 | 0.737 | −0.370 | −0.535 | 0.102 | 0.004 |

| (H7) Having children would limit my career | −0.060 | −0.131 | 0.815 | 0.811 | 0.029 | −0.282 | 0.034 | 0.039 |

| (H8) Being a mother would take too much of my own time | 0.063 | −0.016 | 0.640 | 0.741 | −0.292 | −0.534 | −0.148 | −0.062 |

| (H9) Having children would limit my study opportunities | 0.004 | −0.072 | 0.861 | 0.831 | 0.080 | −0.260 | 0.053 | 0.081 |

| (H10) Having children would limit socializing with my friends | 0.088 | 0.110 | 0.847 | 0.727 | 0.287 | −0.055 | −0.011 | 0.028 |

| (H11) It is important for me to choose when to get pregnant | 0.111 | 0.110 | 0.0.287 | 0.519 | −0.645 | −0.753 | −0.174 | −0.042 |

| (H12) It is important for me to have my own stable economy when I have children | −0.015 | 0.141 | −0.029 | 0.301 | −0.840 | −0.833 | 0.053 | 0.141 |

| (H3) Childbearing does not fit into my life right now | −0.364 | −0.256 | 0.0.361 | 0.605 | −0.523 | −0.620 | 0.126 | 0.047 |

| (S3) It is important to me that the child is born in a nuclear family, i.e., mother, father, children | 0.227 | 0.388 | −0.082 | 0.209 | −0.800 | −0.811 | 0.065 | 0.248 |

| (S4) When I have children, my life must be prepared for living with children | 0.234 | 0.401 | −0.093 | 0.206 | −0.819 | −0.828 | 0.072 | 0.259 |

| (S5) It is important for me to have a stable relationship when I have children | 0.227 | 0.391 | −0.047 | 0.243 | −0.822 | −0.842 | −0.046 | 0.162 |

| (S1) My fertility makes me feel communion with other women | −0.034 | 0.324 | 0.028 | 0.077 | −0.027 | −0.129 | 0.849 | 0.839 |

| (S2) Being fertile is important for my identity as a woman | 0.186 | 0.523 | −0.012 | −0.013 | 0.040 | −0.077 | 0.814 | 0.887 |

| (S6) Becoming a mother is important for my identity as a woman | 0.381 | 0.641 | −0.057 | −0.087 | 0.04 | −0.064 | 0.622 | 0.775 |

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–25 | 1552 | 71.5% |

| 26–35 | 372 | 17.1% |

| 36–49 | 248 | 11.4% |

| Marital status | ||

| Non-married | 1568 | 72% |

| Currently Married | 604 | 28% |

| Polygamy | ||

| First wife | 688 | 31.7% |

| Second, third, fourth wife | 45 | 2.1% |

| Unmarried | 1439 | 66.2% |

| Education | ||

| Postgrad degree | 141 | 6% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1691 | 78% |

| High school or less | 340 | 16% |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 1328 | 61% |

| Employed | 309 | 14% |

| Unemployed | 535 | 25% |

| Residence | ||

| Western region | 692 | 31.9% |

| Central region | 886 | 40.8% |

| Northern region | 142 | 6.5% |

| Eastern region | 278 | 12.8% |

| Southern region. | 174 | 8% |

| Kids | ||

| No | 1685 | 77.6% |

| Yes | 487 | 22.4% |

| Pregnant | ||

| No | 2090 | 96.2% |

| Yes | 82 | 3.8% |

| Living with parents | ||

| No | 194 | 8.9% |

| Yes | 1978 | 91.1% |

| Income | ||

| Enough | 1133 | 52.2% |

| Enough with saving | 535 | 24.6% |

| Not enough | 354 | 16.3% |

| In debt | 150 | 6.9% |

| Contraceptives | ||

| No | 1939 | 89.3% |

| Yes | 233 | 10.7% |

| Medical condition | ||

| No | 1910 | 87.9% |

| Yes | 262 | 12.1% |

| Infertility problem | ||

| No | 2107 | 97.0% |

| Yes | 65 | 3.0% |

| Self-reported Psychiatric disorder | ||

| No | 1813 | 83.5% |

| Yes | 359 | 16.5% |

| Decision to have kids | ||

| First year of marriage | 206 | 9.5% |

| After the first year of marriage | 733 | 33.7% |

| After the first 2 years of marriage | 744 | 34.3% |

| Not decided | 489 | 22.5% |

| Preferable sex | ||

| No | 1359 | 62.6% |

| Yes | 813 | 37.4% |

| Items | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| (F1) I look forward to one day becoming a mother | 3.15 ± 1.46 [1–5] |

| (F2) Having children is an essential part of life | 3.11 ± 1.44 [1–5] |

| (F3) Having children will develop me as a person | 2.99 ± 1.38 [1–5] |

| (F4) I find it hard to imagine living a life without children | 2.60 ± 1.25 [1–5] |

| (F5) I can imagine being pregnant and giving birth | 2.83 ± 1.35 [1–5] |

| (F6) Having a child is a way for me to add new elements in life | 2.91 ± 1.38 [1–5] |

| (F7) I talk to my friends about having children in the future | 2.49 ± 1.24 [1–5] |

| (F8) It is important for me to be fertile | 3.13 ± 1.44 [1–5] |

| (F9) It is important for me to be able to get pregnant anytime | 2.99 ± 1.39 [1–5] |

| (H1) Having children would limit my life right now | 2.59 ± 1.15 [1–5] |

| (H2) An unplanned pregnancy would hinder me in my current life | 2.69 ± 1.27 [1–5] |

| (H3) Childbearing does not fit into my life right now | 2.85 ± 1.43 [1–5] |

| (H4) Taking responsibility for a child does not fit into my current life | 2.80 ± 1.41 [1–5] |

| (H5) Having children would limit my leisure time activities | 2.78 ± 1.30 [1–5] |

| (H6) I do not want to take responsibility as a mother now | 2.72 ± 1.41 [1–5] |

| (H7) Having children would limit my [1–5] | 2.55 ± 1.19 [1–5] |

| (H8) Being a mother would take too much of my own time | 2.88 ± 1.37 [1–5] |

| (H9) Having children would limit my study opportunities | 2.55 ± 1.19 [1–5] |

| (H10) Having children would limit socializing with my friends | 2.31 ± 1.06 [1–5] |

| (H11) It is important for me to choose when to get pregnant | 3.26 ± 1.45 [1–5] |

| (H12) It is important for me to have my own stable economy when I have children | 3.66 ± 1.49 [1–5] |

| (S1) My fertility makes me feel communion with other women | 2.60 ± 1.16 [1–5] |

| (S2) Being fertile is important for my identity as a woman | 2.62 ± 1.28 [1–5] |

| (S3) It is important to me that the child is born in a nuclear family, i.e., mother, father, children | 3.76 ± 1.47 [1–5] |

| (S4) When I have children, my life must be prepared for living with children | 3.72 ± 1.48 [1–5] |

| (S5) It is important for me to have a stable relationship when I have children | 3.85 ± 1.47 [1–5] |

| (S6) Becoming a mother is important for my identity as a woman | 2.76 ± 1.36 [1–5] |

| AFCS TOTAL | 79.14 ± 19.4 [27–135] |

| Attributes | Importance for Future | Hindrance at Present | Childbearing Preparation | Female Identity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x̄ ± SD | p-Value (Effect Size) | x̄ ± SD | p-Value (Effect Size) | x̄ ± SD | p-Value (Effect Size) | x̄ ± SD | p-Value (Effect Size) | ||

| Age (Years) | 18–25 | 25.54± 9.08 ≠¥ | p < 0.001 (0.01) ** | 25.66 ± 8.66 ≠¥ | p < 0.001 (0.05) ** | 18.53 ± 5.08 ≠¥ | p < 0.001 (0.02) ** | 10.37 ± 3.41 ≠¥ | 0.500 (0.01) ** |

| 26–35 | 27.72 ± 9.97 β | 22.12 ± 7.16 β | 17. 87± 5.56 β | 10.31 ± 3.70 β | |||||

| 36–49 | 28.04 ± 10.35 β | 19.92 ± 7.01 β | 16.75 ± 5.24 β | 10.09 ± 4.02 β | |||||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 25.23 ± 8.87 | p < 0.001 (0.36) * | 25.71 ± 8.58 | p < 0.001 (0.59) * | 18.46 ± 5.08 | p < 0.001 (0.17) * | 10.33 ± 3.40 | 0.969 (0.00) * |

| Married | 28.73 ± 10.38 | 20.99 ± 7.25 | 17.55 ± 5.50 | 10.33 ± 3.86 | |||||

| Polygamy | First wife | 27.99 ± 10.38 ¥ | p < 0.001 (0.02) ** | 21.30 ± 7.41 ¥ | p < 0.001 (0.06) ** | 17.62 ± 5.67 ¥ | p < 0.001 (0.02) ** | 10.27 ± 3.87 ¥ | 0.173 (0.01) ** |

| Second, third, fourth wife | 26.31 ± 9.90 | 20.60 ± 7.56 | 16.27 ± 5.35 | 9.42 ± 4.03 | |||||

| Unmarried | 25.34 ± 8.83 | 26.00 ± 8.57 | 18.56 ± 4.94 | 10.33 ± 3.35 | |||||

| education | Postgrad degree | 26.20 ± 9.80 | 0.454 (0.000) ** | 22.09 ± 6.84 ≠ | 0.003 (0.004) ** | 17.67 ± 5.46 | 0.305 (0.003) ** | 10.04 ± 3.66 | 0.242 (0.000) ** |

| Bachelor Degree | 26.32 ± 9.49 | 24.62 ± 8.55 β | 18.29 ± 5.15 | 10.40 ± 3.47 | |||||

| High school or less | 25.61 ± 9.06 | 24.23 ± 8.72 | 18.02 ± 5.39 | 10.11 ± 3.77 | |||||

| Occupation | Student | 25.42 ± 9.10 ≠¥ | p < 0.001 (0.01) ** | 25.92 ± 8.82 ≠¥ | p < 0.001 (0.04) ** | 18.55 ± 5.15 ≠¥ | 0.001 (0.01) ** | 10.35 ± 3.40 ≠¥ | 0.948 (0.01) ** |

| Employed | 28.02 ± 10.36 β | 21.79 ± 7.63 β | 17.76 ± 5.59 β | 10.28 ± 3.77 β | |||||

| Unemployed | 27.07 ± 9.53 β | 22.12 ± 7.21 β | 17.64 ± 5.08 β | 10.32± 3.72 β | |||||

| Residence | Western region | 26.50 ± 9.32 α | p < 0.001 (0.01) ** | 23.66 ± 8.16 α | p < 0.001 (0.01) ** | 18.19 ± 5.25 α | 0.001 (0.01) ** | 10.47 ± 3.59 α | 0.001 (0.01) ** |

| Central region | 26.62 ± 9.49 α | 25.52 ± 8.82 α | 18.61 ± 4.90 α | 10.47 ± 3.36 α | |||||

| Northern region | 25.82 ± 9.76 α | 22.42 ± 8.07 α | 17.01 ± 6.08 α | 9.37 ± 3.87 α | |||||

| Eastern region | 26.56 ± 9.43 α | 24.32 ± 7.84 α | 18.27 ± 5.15 α | 10.45 ± 3.56 α | |||||

| Southern region | 22.59 ± 8.74 | 23.36 ± 8.82 | 17.15 ± 5.66 | 9.67 ± 3.70 | |||||

| Kids | No | 25.53 ± 9.02 | p < 0.001 (0.31) * | 25.35± 8.53 | p < 0.001 (0.53) * | 18.42 ± 5.08 | p < 0.001 (0.18) * | 10.35 ± 3.42 | 0.615 (0.02) * |

| Yes | 28.53 ± 10.47 | 21.09 ± 7.51 | 17.47 ± 5.60 | 10.26 ± 3.91 | |||||

| Pregnant | No | 26.07 ± 9.38 | p < 0.001 (0.01) * | 24.53 ± 8.52 | p < 0.001 (0.03) * | 18.22 ± 5.20 | 0.600 (0.12) * | 10.33 ± 3.53 | 0.823 (0.02) * |

| Yes | 29.57 ± 10.41 | 21.15 ± 7.26 | 17.91 ± 5.54 | 10.24± 3.69 | |||||

| Living with parents | No | 26.29 ± 10.04 | 0.890 (0.01) * | 23.95± 8.90 | 0.440 (0.02) * | 18.21 ± 5.52 | 0.998 (0.00) * | 10.45 ± 3.66 | 0.609 (0.01) * |

| Yes | 26.19 ± 9.39 | 24.44 ± 8.46 | 18.21 ± 5.18 | 10.32 ± 3.52 | |||||

| Income | Enough | 26.27 ± 9.46 | 0.235 (0.001) ** | 24.37 ± 8.54 | 0.843 (0.000) ** | 18.20 ± 5.24 | 0.867 (0.000) ** | 10.40± 3.57 | 0.646 (0.000) ** |

| Enough with saving | 26.68 ± 9.49 | 24.62 ± 8.53 | 18.36 ± 5.01 | 10.23 ± 3.38 | |||||

| Not Enough | 25.40 ± 9.20 | 24.34 ± 8.52 | 18.09 ± 5.42 | 10.19 ± 3.61 | |||||

| In debt | 25.80 ± 9.64 | 23.93 ± 8.08 | 18.07 ± 5.23 | 10.47 ± 3.64 | |||||

| Contraceptives | No | 26.13 ± 9.37 | 0.316 (0.01) * | 24.69 ± 8.56 | p < 0.001 (0.12) * | 18.28 ± 5.18 | 0.070 (0.05) * | 10.36 ± 3.50 | 0.329 (0.01) * |

| Yes | 26.79 ± 10.02 | 21.93 ± 7.49 | 17.63 ± 5.45 | 10.12 ± 3.79 | |||||

| Medical condition | No | 26.21 ± 9.31 | 0.834 (0.01) * | 24.57 ± 8.42 | 0.010 (0.03) * | 18.25 ± 5.14 | 0.293 (0.08) * | 10.37 ± 3.49 | 0.184 (0.01) * |

| Yes | 26.08 ± 10.36 | 23.13 ± 8.93 | 17.89 ± 5.71 | 10.06 ± 3.85 | |||||

| Infertility problems | No | 26.18 ± 9.38 | 0.522 (0.03) * | 24.51 ± 8.47 | 0.001 (0.23) * | 18.24 ± 5.19 | 0.113 (0.12) * | 10.34 ± 3.52 | 0.263 (0.03) * |

| Yes | 26.94 ± 11.38 | 20.86 ± 8.60 | 17.20 ± 5.74 | 9.85 ± 3.97 | |||||

| Psychiatric Disorder | No | 26.48 ± 9.41 | 0.002 (0.13) * | 24.01 ± 8.30 | p < 0.001 (0.12) * | 18.10 ± 5.19 | 0.027 (0.05) * | 10.35 ± 3.57 | 0.489 (0.01) * |

| Yes | 24.76 ± 9.51 | 26.38 ± 9.19 | 18.77 ± 5.30 | 10.21 ± 3.37 | |||||

| Decision of Having kids | First year of marriage | 29.15 ± 10.98 ¥ | p < 0.001 (0.01) ** | 19.84 ± 7.90 ≠¥ | p < 0.001 (0.01) ** | 17.32 ± 5.98 ≠¥ | p < 0.001 (0.02) ** | 10.09 ± 4.04 ≠¥ | p < 0.001 (0.001) * |

| After the first year of marriage | 28.77 ± 9.69 | 22.46 ± 7.20 | 18.40 ± 5.22 | 10.92 ± 3.63 | |||||

| After first 2 year of marriage | 25.20 ± 8.53 | 26.40 ± 8.59 | 18.75 ± 5.05 | 10.45 ± 3.28 | |||||

| Not decided | 22.63 ± 8.17 | 26.19 ± 9.02 | 17.48 ± 4.98 | 9.36 ± 3.32 | |||||

| Preferable sex | No | 25.86 ± 9.42 | 0.30 (0.05) * | 24.03 ± 8.53 | 0.009 (0.03) * | 17.94 ± 5.27 | 0.002 (0.02) * | 10.20 ± 3.59 | 0.031 (0.001) * |

| Yes | 26.77 ± 9.46 | 25.01 ± 8.42 | 18.66 ± 5.08 | 10.54 ± 3.43 | |||||

| Total | 26.20 ± 9.44 | 24.40 ± 8.50 | 18.21 ± 5.21 | 10.33 ± 3.54 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

AlAteeq, D.A.; Alenzi, E.O.; Alamri, R.A.; Aloraini, A.A.; Alassaf, D.S.; Almutlaq, N.I.; Aloglla, S.S.; Almajhad, A.A.; Jahhaf, R.H. Women’s Attitudes Toward Fertility and Childbearing: A National Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2616. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202616

AlAteeq DA, Alenzi EO, Alamri RA, Aloraini AA, Alassaf DS, Almutlaq NI, Aloglla SS, Almajhad AA, Jahhaf RH. Women’s Attitudes Toward Fertility and Childbearing: A National Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. 2025; 13(20):2616. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202616

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlAteeq, Deemah Ateeq, Ebtihag O. Alenzi, Reema Abdulrahman Alamri, Abeer Abdulkarim Aloraini, Dimah Saif Alassaf, Nujud Ibrahim Almutlaq, Shatha Saleh Aloglla, Albatool Abdullah Almajhad, and Rana Hussain Jahhaf. 2025. "Women’s Attitudes Toward Fertility and Childbearing: A National Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia" Healthcare 13, no. 20: 2616. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202616

APA StyleAlAteeq, D. A., Alenzi, E. O., Alamri, R. A., Aloraini, A. A., Alassaf, D. S., Almutlaq, N. I., Aloglla, S. S., Almajhad, A. A., & Jahhaf, R. H. (2025). Women’s Attitudes Toward Fertility and Childbearing: A National Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare, 13(20), 2616. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202616