Abstract

Background and Objectives: Accurate assessment of Dental fear and anxiety (DFA) is crucial for effective management, yet the vast array of measurement tools presents a dilemma for clinicians and researchers in selecting appropriate methods. This literature review aims to provide a comprehensive review and comparison of the commonly used DFA measurement tools in the pediatric dentistry literature. Methods: A Comprehensive literature search was conducted in December 2024 using the electronic databases PubMed, MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. The search was limited to studies focused on identifying research relevant to DFA in children. For each DFA tool, information on its structure, validity, reliability, strengths, limitations, and target population was recruited and tabulated. A comparison between the DFA tools was then conducted. Quality assessment was performed using Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PRO). Results: The search identified 15 subjective and 5 objective tools. Subjective tools included self-reported scales and pictorial analogs, while objective measures involved physiological monitoring and behavioral observation. While subjective tools offer valuable insights into a child’s self-perceived anxiety, their applicability is influenced by age and cognitive development. Objective measures provide quantifiable data, but require specialized equipment and trained observers. Tools combining simplicity, visual aids, and robust validation were found to be most practical for clinical use. Conclusions: A wide range of valid and reliable tools are available to assess DFA in children. Selection should be tailored to the child’s age, cognitive abilities, clinical setting, and clinician training. Combining subjective and objective assessments may enhance diagnostic accuracy.

1. Introduction

Dental fear and anxiety (DFA) is a typical emotional response in dental settings, affecting individuals across all age groups. In many cases, anxiety experienced during adolescence or adulthood originates from childhood experiences [1]. Therefore, early diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of DFA in children may contribute to better long-term mental health outcomes.

Globally, the prevalence of DFA in children is estimated to range between 20% and 30% [2], and is influenced by factors such as age, cultural background, socioeconomic status, and environmental exposures [3]. Several risk factors have been identified in the etiology of DFA in children, and these are often shaped by dynamic variables such as age, culture, environmental exposures, and generational shifts [4,5,6,7]. These variations highlight the importance of continuous assessment and a thorough understanding of DFA measurement tools [8].

DFA poses significant challenges to the effective delivery of dental care [9]. It often leads to avoidance behaviors, resulting in poor oral health, increased dental neglect, and a higher likelihood of emergency dental treatments [10,11]. Additionally, DFA can have a negative impact on a child’s self-esteem and overall quality of life [12]. Accurate assessment of DFA is, therefore, critical; early identification allows for timely intervention and the prevention of long-term psychological and physical consequences [13]. Nevertheless, pediatric dentists and caregivers must comprehend the factors that lead to subjective dental fear in children, the consequences of untreated anxiety, and the available techniques for assessing and dealing with it [4,5,7,14].

Assessment tools for DFA vary widely. Some of them are subjective tools, determined by the respondent’s viewpoint, while objective tools depend on observed behaviors and the examiner’s interpretation. Subjective dental fear, unlike objective measurement, relies on the child’s perspective and emotional reaction, rather than directly observable or measurable factors, such as physiological responses [15]. Additionally, whosoever responds to the assessment, whether the child, parent, dentist, or another observer, can significantly impact the results [16,17,18,19].

Pediatric dentists must assess a child’s mental health status and level of DFA before initiating treatment. This includes being familiar with the DFA measurement tools. Although there is a systematic review that compares the outcomes of different DFA tools [20] and a review that assesses studies using these tools [21], there is a shortage of reviews that specifically describe the DFA tools used to evaluate pediatric patient fear and anxiety in the dental clinics in a comprehensive and organized manner.

Therefore, this study aimed to provide a review, evaluation, and comparison of the commonly used DFA measurement scales and tools in the literature of pediatric dentistry, in order to guide clinicians and researchers in selecting appropriate tools for assessing and managing DFA effectively.

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify all tools used to assess dental fear and anxiety (DFA) in children, including both subjective and objective measures. In addition, studies evaluating the validity and reliability of DFA tools were included. The search was performed in December 2024 using the electronic databases PubMed, MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. The following keywords and Boolean operators were used to retrieve relevant articles: (“dental fear” OR “dental anxiety”) AND (“children” OR “child”) AND (“anxiety scale” OR “anxiety tools”).

The search inclusion criteria included the following: 1—The recruited instrument should be designed specifically for children or have been validated for use in children. 2—The study exclusively assesses dental fear and anxiety. The exclusion criteria were 1—adapted from different tools, 2—tools designed for adults and not used for children, and 3—tools that originally assessed other than DFA, such as pain, and were used in a study to assess DFA.

Search results were screened stepwise: titles, abstracts, and finally, full manuscripts, based on the study aims and eligibility criteria. Eligible studies were reviewed, and data regarding each DFA tool was extracted. Each DFA tool was summarized and tabulated in terms of its definition, validity, reliability, target population, and scoring methods.

A comparative evaluation of DFA tools was conducted, and the strengths and limitations of the subjective tools and DFA scoring items were assessed using the Francis DO et al. It included a Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PRO) checklist, where we used conceptual model (three-items), Content Validity (three-items), Reliability (three-items), Construct Validity (three-items), Scoring & Interpretation (three-items), and Respondent Burden & Presentation (three-items), Ref. [22]; therefore, the scoring will be out of eighteen.

The strengths and limitations of objective physiological measurement tools were evaluated based on Lu JK. et al. 2024 [23] four criteria where adopted from the original paper: continuous monitoring capability (where it will be ideal if the monitoring was constant), device availability and suitability (it will be suitable if it was non-invasive), feasibility of use (it will be ideal if we can use it in research), and cost evaluation (it will be suitable if it come in a low cost).

The search and data extraction was conducted independently by three evaluators (MB, YS, MA). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with experts (HS and OF).

3. Results

Initially, 40 DFA assessment tools were identified from the search results. Eighteen instruments were selected for comprehensive assessment and inclusion in the study, following a screening for relevance and alignment with the aims of this review. Two scales were excluded because they aimed to measure pain in children, eighteen because it assessed DFA in adults, and two because they evaluated negative beliefs towards dentists. The tools are first classified into subjective and objective measurements, and then into their essential characteristics, validity, reliability, and applicability in pediatric dental settings.

3.1. Subjective Measurements of DFA

Subjective dental fear pertains to the internal feeling of worry or anxiety that a child has before or during a dental appointment. Subjective dental fear, unlike objective measurements, relies on the child’s perspective and emotional reaction, rather than directly observable or measurable factors, such as physiological responses. Pediatric dentists and caregivers must understand the factors that lead to subjective dental fear in children, the consequences of untreated anxiety, and the techniques that are available for assessing and dealing with it.

3.1.1. Corah Dental Anxiety Scale (C-DAS)

Definition: The C-DAS is a self-report scale designed to measure a patient’s level of anxiety about visiting and being at the dentist’s office [24].

Developed by Corah in 1969 [25].

Validity and reliability: C-DAS demonstrated a stability score of 0.77 when tested twice within one week. It also showed significant correlations with other anxiety measures, including the Dental Anxiety Question (DAQ) (r = 0.77, indicating a strong positive relationship), and the State Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) (r = 0.40–0.58, indicating weak to moderate positive relationships (p < 0.01), showing statistical significance [26].

Target population: While C-DAS is primarily designed for adults, some studies have used it for children aged 8 years and above [26,27,28].

Scoring: It consists of four questions with five answers (a 5-point scale from 1 to 5) for each question [29]. The overall dental anxiety score is derived by totaling the scores of the four questions (ranging from 4 to 20); the higher the score, the higher the level of dental anxiety (Table 1).

Table 1.

Corah Dental Anxiety Scale (C-DAS).

3.1.2. Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS)

Tool Definition: The MDAS was introduced as a modified version of the C-DAS. It is a commonly used and validated instrument with which to evaluate dental anxiety in patients.

Developed by Humphris et al. in 1995 [30].

Tool validation and reliability:

The MDAS has demonstrated internal consistency in children, ranging from α = 0.799 to 0.875 across samples [31,32,33]. Criterion validity was supported by correlations with the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule Dental Subscale (CFSS-DS) and a single fear question (r = 0.44–0.58). Construct validity was supported, as children reported lower anxiety during orthodontic treatment compared to higher anxiety when treatment involved local anesthesia [33]. It has also been validated in Arabic, Spanish, Greek, Chinese, Turkish, Romanian, and Tamil [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

Target population: While MDAS is primarily designed for adults, some studies have included children aged 8 years and above [18,42].

Scoring: The MDAS differs from the original DAS by adding an extra question that enquires about the patient’s anxiety just before receiving a local anesthetic injection and secondly, by standardizing the response options across all questions, using a consistent 5-point Likert scale to measure the level of anxiety: not anxious (1), slightly anxious (2), fairly anxious (3), very anxious (4), and extremely anxious (5). Similar to the DAS, the total score is calculated by totaling the scores, resulting in a range from 5 to 25, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety [30] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS).

3.1.3. Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale (MCDAS)

Tool Definition: MCDAS is a modified scale of C-DAS, designed to offer an improved degree of sensitivity and precision in assessing dental anxiety among children [18].

Developed by Wong et al. in 1998 [43].

Tool validation and reliability: The MCDAS demonstrated internal consistency, with item-total correlations ranging from r = 0.60 to 0.74, and Cronbach’s alpha values comparable to those of the Corah Dental Anxiety Scale (C-DAS) and the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale (CFSS-DS). Test–retest reliability demonstrated high stability over one week. Validity was supported by strong correlations with the C-DAS and Dental Fear Schedule Subscale-Short Form (DFSS-SF) (r > 0.70), while construct validity was indicated by higher scores in girls (mean = 20.8) compared to boys (mean = 15.6) and by greater anxiety in older children compared to younger ones. The MCDAS was validated for children aged 8 to 15 years [43]. It has also been validated in Italian and Nepali [44,45].

Target population: The MCDAS is a reliable and valid self-reported scale for assessing dental anxiety in children aged 8 to 15 years [42,43].

Scoring: The scale comprises eight questions designed to assess dental anxiety related to specific dental procedures. Each question is to be answered with a five-point Likert scale, which includes scores ranging from relaxed/not worried (1), slightly worried (2), fairly worried (3), more worried (4), and very worried (5). The total score ranges from 8 to 40, with Higher scores indicating greater dental anxiety (Table 3).

Table 3.

Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale (MCDAS).

3.1.4. The Faces Version of the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale (MCDASf)

Tool Definition: It is developed as a modification to the MCDAS by adding a faces analog scale anchored above the original numeric form.

Developed by Howard et al. in 2007 [18].

Tool validation and reliability: The MCDASf in children aged 5 to 12 years demonstrated internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.82), test–retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.80), and criterion validity through correlation with the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale (r = 0.80). Construct validity was supported as children evaluated for dental anxiety, with caries, or requiring dental general anesthesia scored higher than those without these conditions. The MCDASf also showed 51% sensitivity and 79% specificity [18]. It has also been validated in Arabic, Turkish, Croatian, Iranian, Malay, and Chinese [46,47,48,49,50,51].

Target population: The MCDASf is a simple, valid, and reliable tool for assessing dental anxiety in young and anxious older children. While Howard et al. validated the MCDASf for children aged 8 to 12 years, they also noted that the scale is suitable for younger children, including those as young as 5 years [18].

Scoring: The questions and scoring are similar to MCDAS (Table 4).

Table 4.

The Faces version of the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale (MCDASf).

3.1.5. Venham Picture Scale (VPS)

Tool Definition: It is a projective, non-verbal tool designed to assess anxiety levels in children, particularly in dental settings [52].

Developed by Venham and Gaulin-Kremer in 1979 [52].

Tool validation and reliability: The VPS in children aged 3 to 8 years demonstrated internal consistency (Kuder–Richardson 20 = 0.838), test–retest reliability over one week (r = 0.70), and construct validity through an inverse correlation with age (r = −0.47) [19]. According to Buchanan and Niven (2002) [53], the Venham Picture Scale (VPS) in children aged 3–18 years showed low mean scores (1.4). It demonstrated concurrent validity through correlation with the Facial Image Scale (r = 0.70, p < 0.001) [53].

Target population: The VPS is beneficial for children between the ages of 3 and 7, who may have difficulty expressing their anxiety verbally [52]. According to Buchanan and Niven (2002) [53], the tool was effective across a wide age range, from 3 to 18 years. It was quick to administer, making it practical for clinical use with very young children [53].

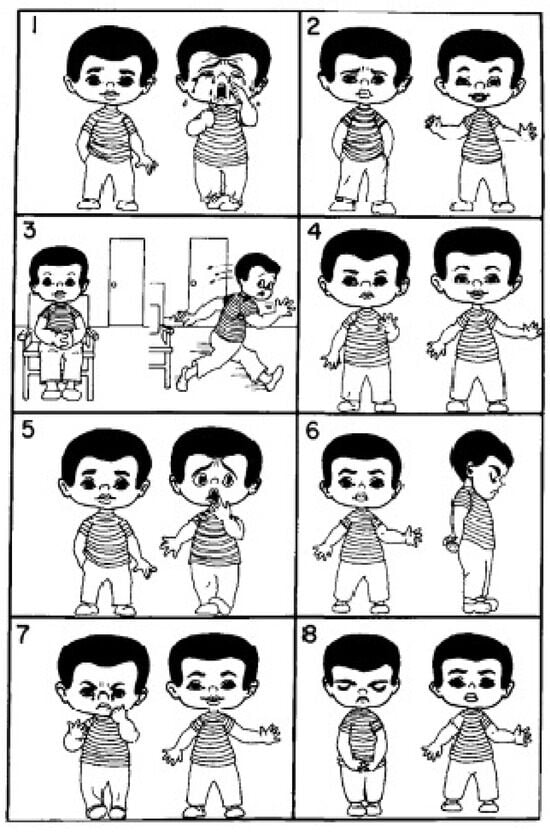

Scoring: The scale consists of eight pairs of images, each showing a child in both an anxious and a calm state. Children are asked to select one image from each pair that best represents how they feel. Each anxious image chosen is scored as 1, while calm selections are scored as 0. The total anxiety score is calculated by totaling the individual scores, with higher totals indicating greater anxiety. The VPS is quick and easy to administer, and it can be used before, during, or after treatment so as to assess a child’s anxiety level [52] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Venham Picture Scale (VPS).

3.1.6. Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale (CFSS-DS)

Tool Definition: It is a widely used tool designed to assess dental fear and anxiety in children [54]. This subscale is part of the larger Children’s Fear Survey Schedule, which evaluates various fears in children.

Developed by Cuthbert and Melamed in 1982 [54].

Tool validation and reliability: The CFSS-DS showed high test–retest reliability (r = 0.97), criterion validity with the Kisling and Krebs behavior rating scale (r = −0.62), and construct validity with higher scores in fearful children (mean 37.8–38.1) compared to non-fearful children (mean 20.9–25.0) [54,55]. It is also validated in Arabic, Chinese, Dutch, Finnish, Japanese, Greek, Hindi, Bosnian, Italian, and Swedish [45,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63].

Target population: The CFSS-DS is commonly applied to children between the ages of 4 and 14 years, as shown in large population-based studies reviewed by Klingberg and Broberg (2007) [64].

Scoring: The scale consists of 15 items describing different dental-related situations or stimuli. Children are asked to rate their fear of each item using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represents “not afraid” and 5 represents “very afraid.” The items include: dentists, doctors, injections, having somebody examine your mouth, having to open your mouth, having a stranger touch you, having somebody look at you, the dentist drilling, the sight and noise of the dentist drilling, instruments in the mouth, choking, having to go to the hospital, people in white uniforms, and having the dentist clean your teeth. The total score is calculated by totaling the responses for all 15 items, which range from 15 to 75. Scores from 15 to 31 indicate low dental anxiety, 32 to 38 suggest moderate dental anxiety, and scores of 39 or above reflect high dental anxiety [42,65] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale (CFSS-DS).

3.1.7. Dental Fear Schedule Subscale-Short Form (DFSS-SF)

Tool Definition: It is a shortened version of the original Dental Fear Schedule (DFS), designed to provide a faster, yet reliable and valid method of measuring dental fear [42,66].

Developed by Foláyan et al. (2003) [67].

Tool validation and reliability: The DFSS-SF was validated for children aged 8 to 13 years, demonstrating internal consistency (α = 0.82) and test–retest reliability (r = 0.73). Criterion validity was supported by a correlation with the Frankl Behavior Rating Scale (r = −0.54), with higher scores in anxious children (mean = 23) compared to non-anxious children (mean = 18.7) [67].

Target population: The DFSS-SF is specifically used to assess dental anxiety in children [66]. It was validated by Folayan et al. (2003) and was used mainly with children aged 8 to 13 years [67].

Scoring: It evaluates fear levels across various dental situations through a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represents “not afraid” and 5 represents “very afraid. The scale includes 12 items: making a dental appointment, walking into the dental office, sitting in the waiting room, seeing dental instruments, hearing the drill, seeing the drill, feeling the vibration of the drill, seeing the injection needle, feeling the injection needle, smelling dental chemicals, undergoing an oral examination, and overall fear of dental treatment. Each response is scored, and the sum of all item scores indicates the child’s overall level of dental fear; higher scores reflect greater anxiety [66] (Table 6).

Table 6.

Dental Fear Schedule Subscale-Short Form (DFSS-SF).

3.1.8. Smiley Faces Program (SFP)

Tool Definition: is a computerized tool designed to assess dental fear and anxiety (DFA) in children [65,68].

Developed by Buchanan in 2005 [68].

Tool validation and reliability: The SFP was validated for children aged 6 to 15 years, demonstrating internal consistency (α = 0.80) and test–retest reliability (r = 0.80). Concurrent validity was supported by correlations with the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale (CFSS-DS) (r = 0.60) and the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale (MCDAS) (r = 0.60). Construct validity was indicated by higher anxiety ratings for invasive procedures (drill and local anesthetic) compared with waiting room and pre-visit situations [68].

Target population: Based on the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS), the SFP is intended for children aged 6 to 15 years [65,68].

Scoring: This interactive tool uses a seven-point animated faces response scale, where children adjust a neutral face to appear happier or sadder according to their anxiety level. The assessment consists of four items, asking children about their feelings toward: having to go to the dentist the next day for treatment, sitting in the waiting room before a dental appointment, having a tooth drilled, and receiving a local anesthetic injection. Children respond on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 represents “very happy” (no anxiety) and 7 indicates “extremely sad or nauseous from anxiety.” The total score ranges from 4 (no DFA) to 28 (most severe DFA), providing a reliable and valid measure of dental anxiety in children [65,68]. The responses the children gave were: 1 = Very happy (no anxiety), 2 = Slightly happy, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Slightly sad, 5 = Sad, 6 = Very sad, 7 = Extremely sad/nauseous from anxiety.

3.1.9. Revised Smiley Faces Program (SFP-R)

Tool Definition: is a computerized tool designed to assess dental fear and anxiety (DFA) in children. It was developed as an improvement on the original Smiley Faces Program (SFP).

Developed by Buchanan in 2005 (2010) [69].

Tool validation and reliability: The SFP-R was validated for children aged 4 to 11 years, demonstrating internal consistency (α = 0.70) and test–retest reliability (r = 0.80). Concurrent validity was supported by a correlation with the MCDAS (r = 0.60), and construct validity was indicated by higher scores in girls and older children [69].

Target population: It is a computerized dental anxiety measure for children aged 4 to 11 years [69].

Scoring: The SFP-R includes an additional item about tooth extraction and an updated animated faces response set, based on child input during small-scale pilot studies. The program is designed using interactive graphics to measure dental fear and anxiety (DFA). Scores for the SFP-R range from 5 (no DFA) to 35 (most severe DFA) [42].

3.1.10. Facial Image Scale (FIS)

Tool Definition: It is a simple, pictorial self-report measure designed to assess dental anxiety in children.

Developed by Buchanan and Niven in 2002 [53].

Tool validation and reliability: According to Buchanan and Niven (2002) [53], the Facial Image Scale (FIS) in children aged 3 to 18 years showed low mean scores (2.2) and no significant effects of age or gender. Concurrent validity was supported through correlation with the Venham Picture Scale (VPS) (r = 0.70, p < 0.001) [53].

Target population: The scale is designed for children and adolescents aged 3 to 18 years [53].

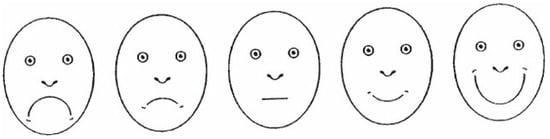

Scoring: The FIS consists of five facial images, ranging from a very happy face to a very unhappy face, illustrating different anxiety levels. Each face is assigned a score from 1 (very happy, no anxiety) to 5 (very unhappy, extreme anxiety). The total score provides an indication of dental anxiety, with higher scores reflecting greater fear [53] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Facial Image Scale (FIS).

3.1.11. Abeer Children’s Dental Anxiety Scale (ACDAS)

Tool Definition: It is a scale designed to measure dental anxiety in children.

Developed by Al-Namankany et al. in 2012 [70].

Tool validation and reliability: The ACDAS was validated for children aged 6 years and above, showing internal consistency (α = 0.90) and test–retest reliability (κ = 0.88–0.90). Concurrent validity was supported by correlation with the CFSS-DS (r = 0.77), and a cutoff score > 26 indicated anxiety (sensitivity 96%, specificity 66%). It is also validated in Arabic, Turkish, Malay, and Spanish [71,72,73,74].

Target population: This scale was specifically designed for children and adolescents aged six and older.

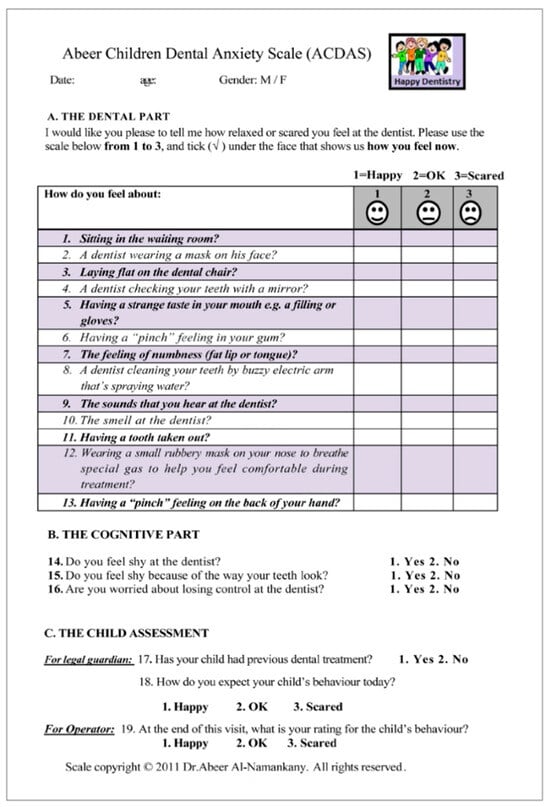

Scoring: The questionnaire consisted of three parts. Part A consists of 13 self-reported questions, arranged in logical order, that ask about the child’s feelings when facing dental experiences. Each question used a 3-face response set. Face 1 represented the feeling of a relaxed, not scared, “happy” person. Face 2 represented a neutral/fair feeling of being “OK.” Face 3 represents the anxious feeling of being “scared.” The child was asked to check under the face that best described his or her response to the question, and a number (1, 2, or 3) was assigned accordingly. The range of values was, therefore, from 13 to 39. The scale indicates that the child is anxious if the score is 26 or higher. 2. Part B comprised three self-reported questions that asked about the child’s feelings of shyness regarding the dentist, or the way his/her teeth looked, and worry about losing control at the dentist; afforded a cognitive assessment; and each required “yes” or “no” as a response. 3. Part C consisted of 3 questions for further assessment of the child, as reported by the legal guardian (to report if the child had a previous experience and how the legal guardian expected his/her child to behave prior to the start of the treatment). The third question was for the dentist to report the child’s behavior at the end of the visit; each question required “yes” or “no” as a response [70] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Abeer Children’s Dental Anxiety Scale (ACDAS).

3.1.12. Children’s Experiences of Dental Anxiety Measure (CEDAM)

Tool Definition: is a child-centered questionnaire designed to assess dental fear and anxiety.

Developed by Porritt et al. in 2018 [75].

Tool validation and reliability: The CEDAM-14 was validated for children aged 9 to 16 years, demonstrating internal consistency (α = 0.88) and test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.98). Rasch analysis confirmed a unidimensional 14-item structure without age or gender bias. Construct validity was supported by higher scores in clinically anxious children, while concurrent validity was demonstrated through a correlation with the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale (MCDAS) (Spearman’s r = 0.67). The CEDAM-14 was also responsive to change, detecting reductions in anxiety after CBT intervention (Cohen’s d = 1.39) [75]. It has additionally been validated in Portuguese and Iranian populations [76,77].

Target population: The CEDAM is validated for use in children aged 9 to 16 years.

Scoring: The CEDAM consists of 14 items, rated on a three-point scale, with total scores ranging from 14 to 42, with higher scores indicating greater dental anxiety. A manual conversion table transforms raw scores into an interval scale, enhancing precision in clinical and research applications [75] (Table 7).

Table 7.

Children’s Experiences of Dental Anxiety Measure (CEDAM).

3.1.13. Shortened Children’s Experiences of Dental Anxiety Measure (CEDAM-8)

Tool Definition: The CEDAM-8 is a shortened version of the Children’s Experiences of Dental Anxiety Measure (CEDAM-14), designed to enhance feasibility in clinical and research settings.

Shortened CEDAM (CEDAM-8).

Developed by Porritt et al. in 2021 [78].

Tool validation and reliability: The CEDAM-8 was validated for children aged 9 to 16 years, showing internal consistency (α = 0.86) with no floor or ceiling effects. Criterion validity was supported by correlation with the CEDAM-14 (r = 0.90), while construct validity was supported by correlation with the global dental anxiety item (r = 0.77). The CEDAM-8 was also responsive to change, detecting meaningful improvement [78].

Scoring: The CEDAM-8 consists of eight items, each rated on a three-point scale, where 0 = Not at all like me, 1 = A bit like me, and 2 = A lot like me. The total score ranges from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating greater levels of dental anxiety [78] (Table 8).

Table 8.

Shortened Children’s Experiences of Dental Anxiety Measure (CEDAM-8).

3.2. Objective Measurements of DFA

Dental patients typically receive recommendations for treatment modalities based on the clinician’s objective assessment, which may involve behavioral management alone, inhalation sedation, intravenous sedation, or general anesthesia [79].

Objective assessments are especially valuable in situations where patients may not provide accurate reports of their anxiety levels due to denial, insufficient self-awareness, or difficulty in communicating.

3.2.1. Venham’s Clinical Anxiety Rating Scale (VCARS)—(Observational Measurement)

Tool Definition: The Venham Clinical Anxiety Rating Scale (VCARS) is an objective behavioral measure designed to assess dental anxiety in children undergoing dental treatment [19].

Developed by Venham et al. in 1977 [19].

Tool validation and reliability: According to Venham et al. (1980), the VCARS was validated in preschool children aged 2 to 5 years, showing high inter-rater reliability (r = 0.78–0.98) and construct validity through significant score differences across sequential visits, and by comparison with physiological measures (heart rate) and the Venham Picture Scale (VPS) [80].

Target population: The target population for VARS is generally children aged 3 to 12 years [80].

Scoring: VARS is constructed of six behaviorally defined categories that range from 0 to 5, with a higher score indicating a higher amount of anxiety. The score gradually increases from relaxed, smiling, willing, and able to converse (Score 0), to the child is totally out of control (Score 5) (Table 9).

Table 9.

Venham Clinical Anxiety Rating Scale (VCARS).

3.2.2. Heart Rate Monitoring (Physiological Measurement)

Increased heart rate is a typical physiological response to anxiety [81]. Measuring heart rate in beats per minute (bmp) during dental visits can offer an objective evaluation of a patient’s level of fear and anxiety. Heart rate monitors and pulse oximeters are used to measure changes in heart rate in response to dental treatment. Elevated heart rate can serve as an indicator of heightened anxiety, thus necessitating the implementation of measures to manage anxiety. It is a safe, non-invasive method that is converted to a numerical score by applying age-specific thresholds. Accurate reference ranges are key to assessing whether a vital sign is abnormal [82]. However, it is not constant, and although in a specific range, it varies between children. Thus, to assess anxiety, two to three measurements are required (before, during, and after the procedure). According to studies, Heart Rate (HR) monitoring was validated in children aged 6 to 12 years, with mean values ranging from 80 to 118 bpm. Validity was supported by correlations with the Corah Dental Anxiety Scale (r = 0.57) and the numeric Visual Facial Anxiety Scale (rs = 0.48) [15,83].

3.2.3. Blood Pressure (Physiological Measurement)

Blood pressure is a useful physiological indicator for evaluating dental anxiety and stress; elevated blood pressure during dental treatment may reflect the patient’s emotional discomfort and anxiety in the clinical environment [84]. Multiple studies found that the increase in blood pressure (BP) correlates with a significant increase in dental anxiety during extraction and local anesthesia [85,86]. The measurement of blood pressure (BP) is usually recorded 5 min before the dental procedure as a baseline, during the dental procedure, and post-procedure to track normalization. According to studies, Blood Pressure (BP) monitoring was validated in children aged 8 to 12 years, with a mean systolic pressure of 125.0 ± 9.4 mmHg and a mean diastolic pressure of 79.9 ± 5.7 mmHg. Validity was supported by a positive correlation between systolic BP and the numeric Visual Facial Anxiety Scale (rs = 0.29), while diastolic BP showed no significant correlation [15].

3.2.4. Salivary Cortisol Levels (Physiological Measurement)

Saliva is widely recognized as a valuable diagnostic tool in healthcare. Due to its non-invasive collection method and diverse composition, it is well-suited for evaluating biomarkers associated with different illnesses [87]. Salivary diagnostics have the potential to detect diseases early, track their progression, and provide individualized treatment options, which could significantly change current healthcare practices [87].

Cortisol, also referred to as the stress hormone, is an essential hormone that is secreted by the adrenal glands in response to stress. It plays a vital role in regulating the body’s stress response and influencing multiple physiological systems. Cortisol levels vary throughout the day, but continuous or extreme stress can result in chronically increased levels, which can have adverse consequences on both physical and mental well-being [88,89]. Salivary Cortisol was validated for children from birth to 14 years of age [87,89]. Salivary cortisol is a reliable indicator of physiological stress due to its association with the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA) axis activity; it is a non-invasive method for children and has the ability to distinguish between children with and without anxiety [90].

The collection methods:

Unsimulated method: This method can be achieved by instructing the individual to allow saliva to accumulate naturally in their mouth before expelling it into a sterile vial or collection tube, ensuring that they avoid swallowing during the process. Alternatively, the Salivette kit instructs the individual to place a sterile cotton swab from the Salivette kit under their tongue or between their gum and cheek without chewing. After approximately two minutes, the cotton swab is removed and placed into the collection tube for subsequent analysis.

The simulated method involves instructing the participant to chew on a sterile cotton swab from the Salivette kit for approximately 1–2 min, stimulating saliva production and saturating the swab. Once adequately saturated, the swab is placed back into the collection tube provided. After saliva collection, the sample should be stored in a sub-zero freezer in order to preserve its integrity until the sample is analyzed using a specialized Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) [91].

3.2.5. Electrodermal Activity (Physiological Measurement)

Electrodermal Activity (EDA) measures the activation of sweat glands, which are solely under sympathetic nervous system control. It is a highly sensitive and somatically independent indicator of sympathetic arousal, making it a valuable tool for assessing the emotional and cognitive responses of children experiencing dental anxiety [84]. It is usually recorded by using an EDA sensor device, 3–5 min before the procedure, during the procedure, and 3 min after the procedure. Higher reading indicates dental anxiety.

EDA was validated for children aged 5 to 13 years and for children with developmental disabilities [92,93]. It also demonstrated reliable functional consistency across clinical settings, particularly in non-verbal and cognitively impaired populations [92,93,94].

Table 10 presents DFA tools along with their age ranges, questions and answers, scales and scoring, strengths, limitations, and notes on validity, reliability, and validated languages. It also reports the quality score of the DFA tools according to the PRO checklist. Supplement Table S1 reports the DFA quality scoring in more detail.

Table 10.

Dental Fear and Anxiety Assessment Tools and Their Characteristics.

All the dental anxiety tools included a detailed explanation of their purpose and target audience. Each tool was developed by experts, and most of the questionnaires were brief and simple to use. In general, studies demonstrated consistent results when the measures were repeated, thus indicating good reliability. Additionally, the tools’ ability to distinguish between children with high anxiety and those with low anxiety, as well as their expected associations with other anxiety measures, provided evidence of their validity.

Despite these advantages, certain disadvantages were noticed. Except for the CEDAM and the CEDAM-8, the majority of the measures were not made to monitor change over time. The fact that none of the tools provided guidance on how to handle missing answers was another disadvantage (Supplement Table S1). Table 11 provides further details regarding each tool’s validity and reliability.

Table 11.

Validity and reliability of DFA tools.

4. Discussion

Assessment tools for Dental Fear and Anxiety (DFA) are important for pediatric dentists to understand and utilize in their daily practice with their patients and in research. Given the numerous DFA tools available in the literature, which vary in complexity, subjectivity, and validation criteria, this review aims to provide a comprehensive summary of these tools in order to support pediatric dentists in their selection and application.

Subjective tools, although generally easier to use, measure anxiety based on the individual’s perception of their symptoms. Factors such as personal experience, cognitive ability, and maturity can influence the results, thereby potentially leading to reporting bias [64,95].

Moreover, the C-DAS and its modified versions, MDAS, offer a brief assessment; however, the need for verbal and cognitive ability limits the use of these tools. In addition, they are both limited in scope, measuring a narrow range of dental situations. The MCDAS and its facial version (MCDASf) are easy to use for children, due to the modification of the questions and the inclusion of faces, and, to a lesser extent, the VPS and FIS. Making them more suitable for younger children.

In contrast, the CFSS-DS and the DFSS-SF provide broader coverage of DFA situations. Still, the need for cognitive ability and the length of the tools remain obstacles to their practical use.

While the SFP and its revised version, SFP-R, are computerized tools that have been developed to enhance the child’s involvement through interactive visual methods, their cost and access to the tools remain a challenge in utilizing them on a broad scale for children, unlike the other tools.

Recent tools have been developed to measure DFA, such as the CEDAM and CEDAM-8, although these tools have demonstrated excellent psychometric properties; however, the length of the scales and the inability to use them with younger children remain significant limitations for the scales. ACDAS overcomes these obstacles by using short, simple questions and incorporating faces so as to facilitate straightforward answers, making it a suitable choice for use in the clinic.

Subjective tools are easy to administer, non-invasive, time-efficient, and offer good validity and reliability. They can be used in different settings with a wide range of children’s ages. Dentists can optimize their use by selecting tools based on the child’s age, literacy level, clinical context, and the purpose of the assessment.

Additionally, multiple studies have evaluated DFA using various tools on the same sample and found no statistically significant differences among them [70,96,97,98,99]. This suggests that their effectiveness in measuring DFA is comparable, allowing dentists flexibility in both clinical application and research. However, studies that utilized DFA tools to assess different behavior management techniques (BMTs) have reported varying outcomes. For example, Bagher et al. compared two types of BMTs and reported similar outcomes related to VCARS, ACDAS, and heart rate, with no significant differences between the techniques. However, salivary cortisol levels showed greater variation between the BMTs [100]. In addition, Khogeer et al. (2025) [101] assessed dental anxiety using FIS, VCARS, and heart rate. They found that changes in dental anxiety across different BMTs were not consistent. The self-reporting tool (FIS) demonstrated greater changes compared to evaluations conducted by an observer, such as the dentist (VCARS). Heart rate changes were greater than those measured by VCARS but less than those measured by FIS [101]. This could also indicate that a child’s self-perception may reflect preference more than actual anxiety. Thus, we recommend using multiple complementary assessment tools in order to achieve a more reliable evaluation of dental anxiety.

To date, there is no universally accepted gold standard for assessing DFA. Consequently, most studies establish criterion validity by comparing outcomes across instruments. In this review, we have summarized the comparisons in Table 11. Therefore, until a gold standard is established, triangulation using multiple validated tools and context-specific validation is recommended.

In addition, multiple DFA tools (CFSS-DS, MDAS, MCDAS, MCDASf, ACDAS, CE-DAM) have been employed across different populations. These tools were translated, validated through face and content validity, and pilot tested to ensure proper cultural adaptation. Moreover, observer-based ratings such as FIS and ACDAS incorporated either culturally neutral or locally relevant imagery and behavioral anchors. Finally, objective physiological measures, such as heart rate, should be interpreted relative to individual resting baselines and culture-specific normative ranges [82].

A notable limitation across all subjective tools is the lack of a strategy for handling missing data, which, if it occurs, could affect the questionnaire and result in measurement bias, jeopardizing the dentist’s decision-making and the choice of a proper treatment plan. It can be overcome by the dentist ensuring that the child answers all the questions and combining clinical judgment with the questionnaire [102].

On the other hand, objective tools do not require the child’s participation in answering questionnaires. It depends on observable symptoms, as examined by clinicians, or on measuring physiological changes [103]. It is particularly valuable for children who are very young or have a cognitive disability.

Venham Clinical Anxiety Rating Scale (VCARS) is a valuable tool for clinicians to use for children of all ages and cognitive states, due to its simplicity and clarity. However, examiners’ calibration and training are vital for using objective clinician evaluation.

Additionally, heart rate is often used to assess a patient’s anxiety by monitoring changes before, during, and after dental treatment. Studies have demonstrated variations in mean heart rate among children subjected to different behavior management techniques, such as Ask-Tell-Ask and Tell-Play-Do, compared to the traditional Tell-Show-Do method [103]. Heart rate is typically used in conjunction with other anxiety measurement approaches to provide a more comprehensive assessment [100,104]. However, a heart rate monitor requires a certain degree of cooperation from the child or assistance from the dental team to be used during the dental visit [105]. Additionally, it is influenced by the child’s level of activity, age, and can vary between genders [106]. It is also affected by the devices.

Moreover, measuring blood pressure is affordable, and the results are standardized, with minimal cooperation from the child. However, studies have shown that blood pressure ranges can vary based on a child’s age, gender, obesity, and geographic location, making it a challenging tool to be used as a reliable indicator for diagnosing anxiety in children [107,108]. Additionally, it lacks continuity of measurement and may be descriptive during dental treatment.

Salivary cortisol is a reasonable measure of anxiety due to its non-invasive method; however, the cost and time required to collect samples before, during, and after, make it impractical to use outside the research setting. Additionally, it has variable ranges and is influenced by multiple variables [106].

EDA is a valuable technique for evaluating DFA in children, where variations in skin conductance levels, influenced by sympathetic nervous system activity, act as physiological markers of anxiety or stress. It is non-invasive and sensitive to acute emotional arousal, making it beneficial for anxiety assessment during dental treatments. Still, it costs more than other tools and could cause discomfort to children during treatment.

While objective tools provide valuable psychological and behavioral data, their practical application is limited by the availability of resources across different settings. Tools like heart rate monitors and blood pressure devices are affordable and available in various clinical settings, unlike salivary cortisol and EDA, which are more challenging to obtain and are mostly used in research settings and specialized environments.

Despite considerable progress in scale development and techniques for identifying anxious children, there remains potential for innovation, particularly with advancements in technology and artificial intelligence that could support the detection and treatment of anxiety. However, the validation and reliability of these tools remain critical areas that require further evaluation and meta-analysis across different populations and age groups so as to have consistently more accurate measurement tools.

5. Conclusions

A wide range of valid and reliable tools are available to assess DFA in children. Selection should be tailored to the child’s age, cognitive abilities, clinical setting, and clinician training. This review serves as a practical reference to aid in evidence-based decision-making for DFA management in pediatric dentistry.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13202597/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., and H.J.S.; methodology, M.B. and H.J.S.; software, M.B., M.A. and Y.T.A.; validation, M.B., M.A., Y.T.A., O.M.F. and H.J.S.; formal analysis, M.B. and H.J.S.; investigation, M.B., M.A. and Y.T.A.; resources, M.B., M.A. and Y.T.A.; data curation, M.B., M.A., Y.T.A., O.M.F. and H.J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, M.B., M.A., Y.T.A. and H.J.S.; visualization, M.B. and H.J.S.; supervision, O.M.F. and H.J.S.; project administration, M.B., O.M.F. and H.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for technical and financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DFA | Dental fear and anxiety |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| C-DAS | Corah Dental Anxiety Scale |

| MDAS | Modified Dental Anxiety Scale |

| MCDAS | Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale |

| MCDASf | Faces version of the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale |

| VPS | Venham Picture Scale |

| CFSS-DS | Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale |

| DFSS-SF | Dental Fear Schedule Subscale-Short Form |

| SFP | Smiley Faces Program |

| SFP-R | Revised Smiley Faces Program |

| FIS | Facial Image Scale |

| ACDAS | Abeer Children’s Dental Anxiety Scale |

| CEDAM | Children’s Experiences of Dental Anxiety Measure |

| CEDAM-8 | Shortened Children’s Experiences of Dental Anxiety Measure |

| VCARS | Venham’s Clinical Anxiety Rating Scale |

References

- Rapee, R.M.; Schniering, C.A.; Hudson, J.L. Anxiety disorders during childhood and adolescence: Origins and treatment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 5, 311–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisolia, B.M.; Dos Santos, A.P.P.; Dhyppolito, I.M.; Buchanan, H.; Hill, K.; Oliveira, B.H. Prevalence of dental anxiety in children and adolescents globally: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2021, 31, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, H.J.; Abdelaziz, W.; Alghamdi, W.; Quritum, M.; AlKhateeb, N.A.; Abourdan, J.; Qureshi, N.; Qureshi, S.; Hamoud, A.H.N.; Mahmoud, N.; et al. Anxiety among Adolescents and Young Adults during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multi-Country Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdullatif, M.M.; Sabbagh, H.J.; Aldosari, F.M.; Farsi, N.M. Birth Order and its Effect on Children’s Dental Anxiety and Behavior during Dental Treatment. Open Dent. J. 2023, 17, e187421062304180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, N.; Faran, L.Y.; Dashash, R.A.; Turkistani, J.; Tallab, H.Y.; Aldosari, F.M.; Alhafi, S.I.; Sabbagh, H.J. The relationship between Body Mass Index and dental anxiety among pediatric patients in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhabes, M.; Al-Obaidi, N. Understanding and addressing pediatric dental Anxiety: A contemporary overview. Al-Azhar J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 27, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, H.J.; Sharton, G.; Almaghrabi, J.; Al-Malik, M.; Hassan Ahmed Hassan, M.; Helal, N. Effect of Environmental Tobacco Smoke on Children’s Anxiety and Behavior in Dental Clinics, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.L.; Thrasher, A.D.; Goldberg, J.; Shea, J.A. A framework for understanding modifications to measures for diverse populations. J. Aging Health 2012, 24, 992–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, H.J.; Turkistani, J.M.; Alotaibi, H.A.; Alsolami, A.S.; Alsulami, W.E.; Abdulgader, A.A.; Bagher, S.M. Prevalence and Parental Attitude Toward Nitrous-Oxide and Papoose-Board Use in Two Dental Referral Centers in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2021, 13, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltes, C.; Giannou, K.; Mantzios, M. Exploring dental anxiety as a mediator in the relationship between mindfulness or self-compassion and dental neglect. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, H.J.; Albeladi, N.H.; Altabsh, N.Z.; Bamashmous, N.O. Risk Factors Associated with Children Receiving Treatment at Emergency Dental Clinics: A Case-Control Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, A.; Freeman, R.; Humphris, G. Dental anxiety, child-oral health related quality of life and self-esteem in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Community Dent. Health 2021, 38, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Namankany, A.; de Souza, M.; Ashley, P. Evidence-based dentistry: Analysis of dental anxiety scales for children. Br. Dent. J. 2012, 212, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaki, S.M.; Al-Raddadi, R.A.; Sabbagh, H.J. Children’s electronic screen time exposure and its relationship to dental anxiety and behavior. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2023, 18, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, N.; Sabherwal, P.; Tyagi, R.; Khatri, A.; Srivastava, S. Relationship between subjective and objective measures of anticipatory anxiety prior to extraction procedures in 8- to 12-year-old children. J. Dent. Anesth. Pain Med. 2021, 21, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.C. Measurement of feelings using visual analogue scales. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1969, 62, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Corah, N.L. Development of a dental anxiety scale. J. Dent. Res. 1969, 48, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, K.E.; Freeman, R. Reliability and validity of a faces version of the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2007, 17, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venham, L.; Bengston, D.; Cipes, M. Children’s response to sequential dental visits. J. Dent. Res. 1977, 56, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Kulkarni, P.; Agrawal, N.; Mali, S.; Kale, S.; Jaiswal, N. Dental Anxiety Scales Used in Pediatric Dentistry: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2021, 22, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porritt, J.; Buchanan, H.; Hall, M.; Gilchrist, F.; Marshman, Z. Assessing children’s dental anxiety: A systematic review of current measures. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2013, 41, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.O.; McPheeters, M.L.; Noud, M.; Penson, D.F.; Feurer, I.D. Checklist to operationalize measurement characteristics of patient-reported outcome measures. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.K.; Wang, W.; Goh, J.; Maier, A.B. A practical guide for selecting continuous monitoring wearable devices for community-dwelling adults. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hain, R.D. Pain scales in children: A review. Palliat. Med. 1997, 11, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.I. What is the gold standard of the dental anxiety scale? J. Dent. Anesth. Pain Med. 2023, 23, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aartman, I.H.; van Everdingen, T.; Hoogstraten, J.; Schuurs, A.H. Self-report measurements of dental anxiety and fear in children: A critical assessment. ASDC J. Dent. Child. 1998, 65, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dogan, M.C.; Seydaoglu, G.; Uguz, S.; Inanc, B.Y. The effect of age, gender and socio-economic factors on perceived dental anxiety determined by a modified scale in children. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2006, 4, 235–241. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, F.A.; Lucas, J.O.; McMurray, N.E. Dental anxiety in five-to-nine-year-old children. J. Pedod. 1980, 4, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Corah, N.L.; Gale, E.N.; Illig, S.J. Assessment of a dental anxiety scale. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1978, 97, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphris, G.M.; Morrison, T.; Lindsay, S.J. The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: Validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent. Health 1995, 12, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Diaz, M.; Crego, A.; Romero-Maroto, M. The influence of gender on the relationship between dental anxiety and oral health-related emotional well-being. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2013, 23, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Diaz, M.; Crego, A.; Armfield, J.M.; Romero-Maroto, M. Treatment experience, frequency of dental visits, and children’s dental fear: A cognitive approach. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2012, 120, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahti, S.; Kajita, M.; Pohjola, V.; Suominen, A. Reliability and Validity of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale Among Children Aged 9 to 12 Years. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, S.A.; Alshammari, S.A.; Baseer, M.A.; Assery, M.K.; Ingle, N.A. Validation of Arabic version of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) and Kleinknecht’s Dental Fear Survey Scale (DFS) and combined self-modified version of this two scales as Dental Fear Anxiety Scale (DFAS) among 12 to 15 year Saudi school students in Riyadh city. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2019, 9, 553–558. [Google Scholar]

- Appukuttan, D.; Datchnamurthy, M.; Deborah, S.P.; Hirudayaraj, G.J.; Tadepalli, A.; Victor, D.J. Reliability and validity of the Tamil version of Modified Dental Anxiety Scale. J. Oral Sci. 2012, 54, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahammam, M.A.; Hassan, M.H. Validity and reliability of an Arabic version of the modified dental anxiety scale in Saudi adults. Saudi Med. J. 2014, 35, 1384–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Coolidge, T.; Arapostathis, K.N.; Emmanouil, D.; Dabarakis, N.; Patrikiou, A.; Economides, N.; Kotsanos, N. Psychometric properties of Greek versions of the Modified Corah Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) and the Dental Fear Survey (DFS). BMC Oral Health 2008, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolidge, T.; Hillstead, M.B.; Farjo, N.; Weinstein, P.; Coldwell, S.E. Additional psychometric data for the Spanish Modified Dental Anxiety Scale, and psychometric data for a Spanish version of the Revised Dental Beliefs Survey. BMC Oral Health 2010, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărginean, I.; Filimon, L. Modified dental anxiety scale: A validation study on communities from the west part of Romania. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Community 2012, 2, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Tunc, E.P.; Firat, D.; Onur, O.D.; Sar, V. Reliability and validity of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) in a Turkish population. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2005, 33, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Freeman, R.; Lahti, S.; Lloyd-Williams, F.; Humphris, G. Some psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale with cross validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2008, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianetti, S.; Lombardo, G.; Lupatelli, E.; Pagano, S.; Abraha, I.; Montedori, A.; Caruso, S.; Gatto, R.; De Giorgio, S.; Salvato, R. Dental fear/anxiety among children and adolescents. A systematic review. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 18, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, H.M.; Humphris, G.M.; Lee, G.T. Preliminary validation and reliability of the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale. Psychol. Rep. 1998, 83, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanduri, N.; Singhal, N.; Mitra, M. The prevalence of dental anxiety and fear among 4–13-year-old Nepalese children. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2019, 37, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paglia, L.; Gallus, S.; de Giorgio, S.; Cianetti, S.; Lupatelli, E.; Lombardo, G.; Montedori, A.; Eusebi, P.; Gatto, R.; Caruso, S. Reliability and validity of the Italian versions of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule—Dental Subscale and the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 18, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arslan, I.; Aydinoglu, S. Turkish version of the faces version of the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale (MCDAS(f)): Translation, reliability, and validity. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 2031–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esa, R.; Hashim, N.A.; Ayob, Y.; Yusof, Z.Y. Psychometric properties of the faces version of the Malay-modified child dental anxiety scale. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabi, M.A.; Hussein, I.; Salami, A.; Awad, R.; Alderei, N.; Wahab, A.; Kowash, M. A study protocol of a single-center investigator-blinded randomized parallel group study to investigate the effect of an acclimatization visit on children’s behavior during inhalational sedation in a United Arab Emirates pediatric dentistry postgraduate setting as measured by the levels of salivary Alpha Amylase and Cortisol. Medicine 2019, 98, e16978. [Google Scholar]

- Javadinejad, S.; Farajzadegan, Z.; Madahain, M. Iranian version of a face version of the Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale: Transcultural adaptation and reliability analysis. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2011, 16, 872–877. [Google Scholar]

- Leko, J.; Škrinjarić, T.; Goršeta, K. Reliability and Validity of Scales for Assessing Child Dental Fear and Anxiety. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2020, 54, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Xia, B.; Wang, J.H.; Xie, P.; Huang, Q.; Ge, L.H. Chinese version of a face version of the modified child dental anxiety scale: Transcultural adaptation and evaluation. Chin. J. Stomatol. 2013, 48, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Venham, L.L.; Gaulin-Kremer, E. A self-report measure of situational anxiety for young children. Pediatr. Dent. 1979, 1, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, H.; Niven, N. Validation of a Facial Image Scale to assess child dental anxiety. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2002, 12, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, M.I.; Melamed, B.G. A screening device: Children at risk for dental fears and management problems. ASDC J. Dent. Child. 1982, 49, 432–436. [Google Scholar]

- Klingberg, G. Reliability and validity of the Swedish version of the Dental Subscale of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule, CFSS-DS. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1994, 52, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesalo, I.; Murtomaa, H.; Milgrom, P.; Honkanen, A.; Karjalainen, M.; Tay, K.M. The Dental Fear Survey Schedule: A study with Finnish children. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 1993, 3, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapostathis, K.N.; Coolidge, T.; Emmanouil, D.; Kotsanos, N. Reliability and validity of the Greek version of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2008, 18, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajrić, E.; Kobašlija, S.; Jurić, H. Reliability and validity of Dental Subscale of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule (CFSS-DS) in children in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Biomol. Biomed. 2011, 11, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Housseiny, A.A.; Alsadat, F.A.; Alamoudi, N.M.; El Derwi, D.A.; Farsi, N.M.; Attar, M.H.; Andijani, B.M. Reliability and validity of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale for Arabic-speaking children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, M.; Jing, Q.; Zhao, J.; Wan, K.; Xu, Q. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2015, 25, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, Y.; Hirakawa, T.; Milgrom, P.; Coolidge, T.; Heima, M.; Mori, Y.; Ishihara, C.; Yakushiji, N.; Yoshida, T.; Shimono, T. The Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale in Japan. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2005, 33, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Pandey, R.K.; Nagar, A.; Dutt, K. Reliability and factor analysis of children’s fear survey schedule-dental subscale in Indian subjects. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2010, 28, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Berge, M.; Hoogstraten, J.; Veerkamp, J.S.; Prins, P.J. The Dental Subscale of the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule: A factor analytic study in The Netherlands. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1998, 26, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingberg, G.; Broberg, A.G. Dental fear/anxiety and dental behaviour management problems in children and adolescents: A review of prevalence and concomitant psychological factors. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2007, 17, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, A. Understanding Dental Fear and Anxiety in Children. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rantavuori, K.; Lahti, S.; Hausen, H.; Seppä, L.; Kärkkäinen, S. Dental fear and oral health and family characteristics of Finnish children. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2004, 62, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folayan, M.O.; Idehen, E.E.; Ufomata, D. The effect of sociodemographic factors on dental anxiety in children seen in a suburban Nigerian hospital. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2003, 13, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, H. Development of a computerised dental anxiety scale for children: Validation and reliability. Br. Dent. J. 2005, 199, 359–362; discussion 351; quiz 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, H. Assessing dental anxiety in children: The Revised Smiley Faces Program. Child Care Health Dev. 2010, 36, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Namankany, A.; Ashley, P.; Petrie, A. The development of a dental anxiety scale with a cognitive component for children and adolescents. Pediatr. Dent. 2012, 34, e219–e224. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Namankany, A. Development of the first Arabic cognitive dental anxiety scale for children and young adults. World J. Meta-Anal. 2014, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, A.; Tüzüner, T.; Baygin, O.; Yılmaz, N.; Sagdic, S. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Abeer Children Dental Anxiety Scale (ACDAS). Contemp. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 2, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafla, A.; Villalobos-Galvis, F.; Ramírez, W.; Yela, D. Propiedades Psicométricas de la Versión Española de la Abeer Children DentalAnxiety Scale (ACDAS) para la Medición de Ansiedad Dental en Niños. Int. J. Odontostomatol. 2017, 11, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Manan, N.M.; Musa, S.; Nor, M.M.D.; Saari, C.Z.; Al-Namankany, A. The Abeer Children Dental Anxiety Scale (ACDAS) cross-cultural adaptation and validity of self-report measures in the Malaysian Children Context (MY-ACDAS). Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2024, 34, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porritt, J.; Morgan, A.; Rodd, H.; Gupta, E.; Gilchrist, F.; Baker, S.; Newton, T.; Creswell, C.; Williams, C.; Marshman, Z. Development and evaluation of the children’s experiences of dental anxiety measure. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2018, 28, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enshaei, Z.; Kaji, K.S.; Saied-Moallemi, Z. Development and validation of the Iranian version of the Children’s Experiences of Dental Anxiety Measure (CEDAM). Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2024, 10, e830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.H.L.; Gavião, M.B.D.; Steiner-Oliveira, C.; Paschoal, M.A.B.; Castilho, A.R.F.; Barbosa, T.D. Translation and cultural adaptation of the Children’s Experiences of Dental Anxiety Measure (CEDAM) to Brazilian Portuguese. Braz. Dent. Sci. 2024, 27, e4177. [Google Scholar]

- Porritt, J.M.; Morgan, A.; Rodd, H.; Gilchrist, F.; Baker, S.R.; Newton, T.; Marshman, Z. A Short Form of the Children’s Experiences of Dental Anxiety Measure (CEDAM): Validation and Evaluation of the CEDAM-8. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kime, S.L.; Wilson, K.E.; Girdler, N.M. Evaluation of objective and subjective methods for assessing dental anxiety: A pilot study. J. Disabil. Oral Health 2010, 11, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Venham, L.L.; Gaulin-Kremer, E.; Munster, E.; Bengston-Audia, D.; Cohan, J. Interval rating scales for children’s dental anxiety and uncooperative behavior. Pediatr. Dent. 1980, 2, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Trotman, G.P.; Veldhuijzen van Zanten, J.; Davies, J.; Möller, C.; Ginty, A.T.; Williams, S.E. Associations between heart rate, perceived heart rate, and anxiety during acute psychological stress. Anxiety Stress Coping 2019, 32, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S.; Thompson, M.; Stevens, R.; Heneghan, C.; Plüddemann, A.; Maconochie, I.; Tarassenko, L.; Mant, D. Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children from birth to 18 years of age: A systematic review of observational studies. Lancet 2011, 377, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersa, S.; Herdiyati, Y.; Tjahajawati, S. Relation of anxiety and pulse rate before tooth exctraction of 6–9 years old children. Padjadjaran J. Dent. 2012, 24, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, R.; Monea, M.; Mihai, A. A Review of the Current Self-Report Measures for Assessing Children’s Dental Anxiety. Acta Medica Transilv. 2020, 25, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, R.G.; Abu-Naim, H.; Ahmad, O.; Akelah, D.; Salem, Y.; Midoun, E. Vital signs changes during different dental procedures: A prospective longitudinal cross-over clinical trial. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 127, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Li, S.; Zhang, R. Effects of dental anxiety and anesthesia on vital signs during tooth extraction. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.A.; Ahmed, A.S.; Durand, R.; Tran, S.D. Saliva as a diagnostic tool for oral and systemic diseases. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2016, 6, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slopen, N.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Shonkoff, J.P. Interventions to improve cortisol regulation in children: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonova, S.; Booij, L.; D’Souza, V.; Crosara, K.T.B.; Siqueira, W.L.; Emami, E. Investigating the association between stress, saliva and dental caries: A scoping review. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, Y.A.; Refai, R.H.; Hussein, M.M.K.; Abdou, M.H.; El Bordini, M.M.; Ewais, O.M.; Hussein, M.F. Association between environmental stress factors, salivary cortisol level and dental caries in Egyptian preschool children: A case-control study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghsh, N.; Mogharehabed, A.; Karami, E.; Yaghini, J. Comparative evaluation of the cortisol level of unstimulated saliva in patients with and without chronic periodontitis. Dent. Res. J. 2019, 16, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, M.; Melmed, R.N.; Sgan-Cohen, H.D.; Parush, S. Effect of sensory adaptation on anxiety of children with developmental disabilities: A new approach. Pediatr. Dent. 2009, 31, 222–228. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, M.; Sgan-Cohen, H.D.; Parush, S.; Melmed, R.N. Influence of adapted environment on the anxiety of medically treated children with developmental disability. J. Pediatr. 2009, 154, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Yang, H.; Chi, H.J.; Chen, H.M. Physiologic and behavioral effects of papoose board on anxiety in dental patients with special needs. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2014, 113, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooijmans, R.; Langdon, P.E.; Moonen, X. Assisting children and youth with completing self-report instruments introduces bias: A mixed-method study that includes children and young people’s views. Psychol. Methods 2022, 7, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkala, S.; Al-Yahya, H.; Honkala, E.; Freeman, R.; Humphris, G. Validating a measure of the prevalence of dental anxiety as applied to Kuwaiti adolescents. Community Dent. Health 2014, 31, 251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.M.; Buchanan, H. Assessing children’s dental anxiety in New Zealand. N. Z. Dent. J. 2010, 106, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuşcu, O.O.; Akyuz, S. Children’s preferences concerning the physical appearance of dental injectors. J. Dent. Child. 2006, 73, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Namankany, A.; Petrie, A.; Ashley, P. Video modelling for reducing anxiety related to the use of nasal masks place it for inhalation sedation: A randomised clinical trial. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2015, 16, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagher, S.M.; Felemban, O.M.; Alandijani, A.A.; Tashkandi, M.M.; Bhadila, G.Y.; Bagher, A.M. The effect of virtual reality distraction on anxiety level during dental treatment among anxious pediatric patients: A randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2023, 47, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khogeer, L.N.; Sabbagh, H.J.; Felemban, O.M.; Farsi, N.M. Puppet play therapy in emergency pediatric dental clinic. A randomized clinical trial. BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, C.J.; Cain, L.E.; Hogan, J.W. Are all biases missing data problems? Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2015, 2, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taschereau-Dumouchel, V.; Michel, M.; Lau, H.; Hofmann, S.G.; LeDoux, J.E. Putting the “mental” back in “mental disorders”: A perspective from research on fear and anxiety. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagher, S.M.; Felemban, O.M.; Alsabbagh, G.A.; Aljuaid, N.A. The Effect of Using a Camouflaged Dental Syringe on Children’s Anxiety and Behavioral Pain. Cureus 2023, 15, e50023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat-McHayleh, N.; Harfouche, A.; Souaid, P. Techniques for managing behaviour in pediatric dentistry: Comparative study of live modelling and tell-show-do based on children’s heart rates during treatment. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2009, 75, 283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sarganas, G.; Schaffrath Rosario, A.; Neuhauser, H.K. Resting Heart Rate Percentiles and Associated Factors in Children and Adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2017, 187, 174–181.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Salloum, A.A.; El Mouzan, M.I.; Al Herbish, A.S.; Al Omar, A.A.; Qurashi, M.M. Blood pressure standards for Saudi children and adolescents. Ann. Saudi Med. 2009, 29, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahaidarah, S.; Alzahrani, F.; Alshinqiti, M.; Moria, N.; Alahwal, F.; Naghi, K.; Abdulfattah, A.; Alharbi, M.; Abdelmohsen, G. Factors influencing blood pressure fluctuation in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia: A retrospective single-center cohort study. Saudi Med. J. 2023, 44, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).