Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected the mental health of frontline healthcare workers. This study investigated the mental health and occupational stressors faced by frontline workers in Selangor during the pandemic. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted using secondary data from the Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Services team, collected from March to August 2020. A total of 4593 frontline workers participated in the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale screening. Results: Mental health symptoms were common among frontline workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, with 14.8% reporting stress, 30.7% anxiety, and 20.4% depression. Female workers had significantly higher odds of all three conditions, with adjusted odds ratios (aOR) of 1.35 (95% CI: 1.10–1.66) for stress, 1.25 (95% CI: 1.07–1.47) for anxiety, and 1.23 (95% CI: 1.03–1.47) for depression. Workers aged 18–30 had higher odds of stress (aOR 1.88; 95% CI: 1.42–2.47), anxiety (aOR 1.74; 95% CI: 1.43–2.12), and depression (aOR 1.80; 95% CI: 1.43–2.27) compared with those over 40. Employment in hospitals was associated with increased odds of all three conditions, with aORs ranging from 1.71 to 2.05. Among 711 respondents who reported occupational stressors, lack of mental health support was the strongest predictor (aORs 4.91–5.20), followed by poor work rotation and conflict with supervisors. Conclusions: Women, younger staff, and hospital workers were more vulnerable to mental health symptoms during the pandemic. Organizational factors, especially limited support and poor work arrangements, played a major role. Targeted mental health services and improved working conditions are needed to support healthcare workers in future emergencies.

1. Introduction

Public health emergencies are events that can overwhelm the routine capabilities of communities to manage health consequences arising from their causative agents. Throughout the history of mankind, the world has witnessed numerous such events, dating back as early as 430 Before the Common Era (B.C.E.), when the Athenian Plague struck the region of Ethiopia. This unknown novel pathogen led to the deaths of one-fourth of the Athenian population, scattered over 400 years [1]. In the mid-14th century, the human species experienced the deadliest pandemic in history, known as the Black Death. It was a type of bubonic plague that resulted in an estimated 200 million casualties across the continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa [2]. The latest pandemic, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), originated from the city of Wuhan, China, causing an exponential increase in healthcare demands, resulting in straining the world’s healthcare system to its breaking point [3]. Planet Earth was then at a standstill, with strict movement control orders in many parts of the world, affecting human daily lives and activities.

As healthcare demands skyrocketed during pandemics, the immense burden on the healthcare system systematically exposed healthcare workers to occupational stress [4]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an 80% increase in the occupational workload among the healthcare workers [5]. Moreover, a study in the United States revealed that 61% of healthcare workers feared the risks of exposure to the virus, 43% suffered from work overload, 49% experienced burnout, and more than one-third had to deal with anxiety or depression [6]. In addition, higher stress levels are found among frontline workers, such as nursing and medical assistants, inpatient and social workers. Similar findings have been observed in countries such as Singapore, China, Saudi Arabia, and Italy [7,8,9,10].

In the context of Malaysian healthcare workers, some articles have discussed mental health within the population [11,12]. However, limited studies addressed mental health stressors among frontline workers [13]. With the increasing likelihood of future outbreaks due to emerging or reemerging diseases, it is crucial to understand and address the mental health status of frontline workers. This is essential to maximize the mental preparedness of the health workforce, subsequently to minimize the effects of occupational stressors, and to prevent any untoward mental health crises during such public health emergencies [14,15]. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the mental health status of frontline workers and its associated factors in Malaysia during the recent COVID-19 pandemic. By identifying key stressors and their associated mental health outcomes, this research seeks to inform the Ministry of Health with regard to the strategies to support and protect the well-being of frontline workers during current and future public health emergencies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Population

Selangor is the most populous state in Malaysia, with a recorded population of approximately 7 million as of the 2020 census [16]. Strategically positioned around Kuala Lumpur, Selangor plays a central role in Malaysia’s economy and transportation infrastructure, including hosting the Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) and Port Klang, Malaysia’s busiest seaport and a major gateway for international trade. The state’s robust transportation network and high concentration of economic activity contribute to significant internal migration and high population mobility [17]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Selangor emerged as one of the hardest-hit regions in Malaysia. It consistently reported the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases nationwide, a trend attributed to its high population density, economic activity, and traveler influx. Consequently, Selangor hosted the largest number of government-designated quarantine centers to manage incoming travelers and high-risk contacts during the containment phase [12]. Given this high disease burden and the operational pressure on local health infrastructure, healthcare workers (HCWs) in Selangor faced exceptional occupational challenges.

2.2. Data Collection

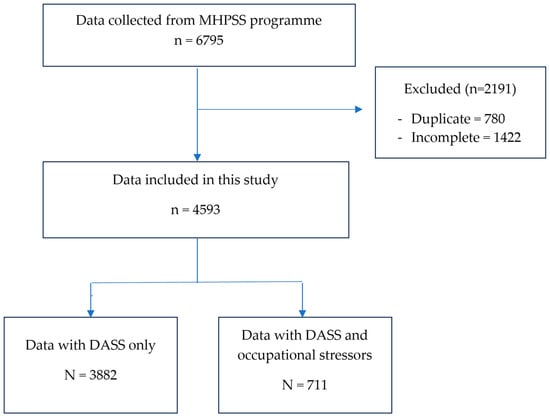

This study utilized secondary data obtained from mental health screening and psychological support activities conducted by the MHPSS team, which consist of data on (1) sociodemographic characteristics, (2) mental health outcomes, and (3) occupational stressors. A universal sampling approach was applied to the MHPSS database, whereby all the registered mental health screenings between March and August 2020 were included in the data collection. A total of 6795 registered data from the MPHSS database were collected for this study. After excluding 2192 data due to duplicates and incomplete information, the final sample comprised 4593 data. Among these, only 711 have complete data for both the DASS and occupational stressors study. These 711 data were all included in the analysis of occupational stressors and mental health outcomes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the data of frontline workers that was included in the study.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29.0) analytics software. Descriptive statistics for sociodemographic characteristics and mental health outcomes were presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical data and means and standard deviations (±SD) for continuous data. Statistical tests were two-sided, with p < 0.05 considered significant. Simple and multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted to explore the effects of various categorical variables (gender, age, ethnicity, healthcare facility, Ministry of Health (MOH) staff, job category, and involvement in outbreak management) on mental health outcomes (stress, anxiety, and depression) using the ENTER method. Independent variables were coded as 1 for reference, and multicollinearity was checked. Model fitness was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and classification table.

3. Results

The results reveal a predominantly female workforce (75.1%) with an average age of 34 years. The majority are Malay (81.0%), working mainly in hospitals (59.1%). Nearly all are MOH staff (98.6%). Mid-level staff formed the largest group (51.4%). A substantial majority (70.9%) were directly involved in outbreak management. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the sample population in detail.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Frontliners at MOH facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Statistical analysis showed no multicollinearity in all the modes with a variance inflation factor (VIF) < 5, indicating no strong correlation between the variables. The models were a good fit based on Hosmer and Lemeshow tests (p-value > 0.05), and the overall classified percentage is acceptable.

There were significant associations between ethnicity, type of healthcare facilities, MOH staff, and job category with mental health status from the crude analysis (Table 2). Malay workers had lower odds of stress and depression compared with non-Malay workers, while MOH staff had lower odds of stress, anxiety, and depression compared with non-MOH staff. However, when adjusted with other factors, both factors had no significant difference in mental health status.

Table 2.

Factors associated with mental health issues/physiological conditions in MOH facilities (N = 4593).

After adjusting for other variables, gender differences were notable, with female workers showing higher odds of stress (AOR = 1.4, 95%CI = 1.0–1.7), anxiety (AOR = 1.3, 95%CI = 1.1–1.5), and depression (AOR = 1.2, 95%CI = 1.0–1.5). Younger workers (18–30 years) experienced higher levels of stress (AOR = 1.9, 95%CI = 1.4–2.5), anxiety (AOR = 1.7, 95%CI = 1.4–2.1), and depression (AOR = 1.8, 95%CI = 1.4–2.3). Respondents working in hospitals and state/district health offices experienced higher stress, anxiety, and depression than those in clinics. The job category was another important factor, with low-level support staff experiencing the least mental health issues. Frontline workers who were involved directly in outbreak management were found to have 22% more odds for stress than frontline workers who were not directly involved with outbreak management.

Table 3 shows occupational stressors and mental health among the frontline workers. The occupational stressors in this study were divided into three groups: working environment, human resources, and organizational support. In multiple logistic regression, poor work rotation and lack of mental health support were associated with mental health. Poor work rotation had higher odds of stress (AOR = 3.1, 95%CI = 1.5–6.5), anxiety (AOR = 2.4, 95%CI = 1.2–4.9), and depression (AOR = 3.2, 95%CI = 1.6–6.5), while lack of mental health support also showed more odds of stress (AOR = 4.9, 95%CI = 2.7–9.1), anxiety (AOR = 5.2, 95%CI = 2.7–9.9), and depression (AOR = 4.4, 95%CI = 2.4–8.0). In contrast, stressors that had no significant association with all three mental health statuses were an unsatisfactory work environment, lack of recognition, and inconsistent leave policies (p-value > 0.05).

Table 3.

Occupational stressors and mental health status (N = 711).

4. Discussion

This study underscores the significant mental health challenges faced by frontline workers in various healthcare settings during the COVID-19 pandemic in Selangor, Malaysia. The findings highlighted that female frontliners were more susceptible to stress, anxiety, and depression. The psychological burden borne by women in healthcare during outbreaks is well documented, and the COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated these gender disparities [23,24,25]. Our results align with findings from a study in Malawi, which reported comparable levels of anxiety among female healthcare workers but a higher prevalence of depression relative to our current study [15]. The heightened impact on women is likely attributable to increased professional workloads compounded by additional caregiving responsibilities at home, particularly in the context of restricted access to schools and childcare services during the pandemic [22,26]. A comprehensive meta-analysis has demonstrated that nations with higher levels of gender inequality had more severe mental health issues among female healthcare workers, encompassing 22 countries across South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa [27]. Although Malaysia was not specifically categorized among the highest-inequality nations in that analysis, the findings provide useful context for interpreting the current study’s results, especially considering the added domestic and family responsibilities that many women managed during the pandemic.

Another notable finding was the impact of workplace stressors across all age groups, with the highest odds ratio observed in the younger age group of 18–30 years. These findings were consistent with studies conducted in Spain and the United States, which also found an association between young age and mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and sleep pattern disturbances [28,29]. This suggested that younger healthcare workers may be less equipped to handle the intense pressures brought about by the pandemic, possibly due to a combination of less professional experience and fewer coping mechanisms [30,31]. Older individuals and experienced healthcare workers may have better psychological strengths acquired from life-challenging experiences, equipping them with skills to deal with the crisis of COVID-19 [32,33]. The lack of human interaction due to movement restrictions further exacerbates stress among younger workers, leading to loneliness and mental health issues [34,35]. These findings emphasize the need for age-specific mental health support to help younger healthcare workers cope with the challenges of the pandemic.

When comparing different levels of workplace environments, frontline workers working as state and district health officers exhibited higher odds of experiencing mental health issues. This disparity is likely attributable to the higher workload in the public health sector, which includes responsibilities such as contact tracing, screening, and surveillance—tasks that have been especially demanding during the COVID-19 emergency [36]. They are often at the forefront of managing public health crises, dealing with an overwhelming influx of cases and the logistical challenges of implementing and maintaining public health measures [37]. Furthermore, the responsibility of screening large populations adds another layer of pressure, as these health officers must ensure accurate and timely testing to control the spread of the virus [38]. Health inspectors working in district health offices have been observed to have the highest prevalence of work-related burnout compared with other healthcare workers in Malaysia [39]. In addition to their regular duties, these health inspectors were heavily involved in the COVID-19 screening, contact tracing, decontamination processes, and response in handling of deceased bodies. Surveillance duties also demand constant vigilance and rapid response to emerging hotspots, further amplifying the mental strain on these workers.

During the COVID-19 crisis, the healthcare system was overwhelmed, and a small number of non-MOH staff, many of them serving as volunteers, stepped in to assist the health sector. Many were assigned to quarantine centers and did not necessarily have a medical background. Although non-MOH staff comprised a small proportion of our sample (1.4%), their data were retained to provide insight into the mental health experiences of this distinct group. They showed higher odds of stress, anxiety, and depression, though estimates should be interpreted with caution due to the limited sample size. Similar findings have been reported elsewhere [40,41]. In Spain, many volunteers reported feeling unprepared due to insufficient supervision, expressed fears of getting infected and infecting their relatives or friends, leading to higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression [40]. Moreover, a cross-sectional study conducted in the United States and China uncovered intriguing results [41]. Volunteers experienced higher levels of mental distress, including depression, anxiety, and somatization. However, they also reported greater levels of happiness compared with those who did not volunteer. The findings of the current research highlighted several critical stressors affecting frontline workers during the national respiratory outbreak, which aligned with results from previous studies. Lack of concerns about workplace safety was a cause for anxiety and depression, which, in contrast with previous studies, indicates that frontline workers often feel vulnerable to infection [15,33]. Lack of concern may be attributed to lack of awareness, training, and perception of infection precautions, subsequently affecting mental health outcomes [42,43]. Poor work rotation had emerged as a significant stressor, mirroring findings from studies in the United States and other countries, which showed that inadequate scheduling and lack of rest breaks contributed to higher psychological stress [44,45,46]. This highlighted the importance of improved work management practices to ensure frontline workers are not overburdened. Furthermore, this current study revealed that the lack of mental health support was significantly associated with higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. This is in line with research from Canada and Slovenia, which highlighted the crucial role of mental health resources and support systems for healthcare workers during public health emergencies [47,48]. Addressing these key stressors is essential to mitigating adverse mental health effects.

5. Recommendation

To address the significant mental health challenges faced by the frontline workers during public health emergencies, such as disease outbreaks and pandemics, we recommend that the Ministry of Health strengthen the existing mental health support systems within healthcare facilities. This includes making mental health screenings more frequent and proactive, strengthening support networks, and ensuring easier access to professional counselling services. Additionally, workplace safety protocols must be enhanced, and work rotation schedules should be optimized to prevent poor mental health outcomes.

6. Limitations

This study was conducted in a single state, which may not fully represent other regions in Malaysia. The cross-sectional design captures a snapshot in time and does not allow for assessment of changes in mental health status over the course of the pandemic. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand how mental health outcomes evolve over time and the lasting impact of public health emergencies. In addition, most participants were female, reflecting the gender distribution of the healthcare workforce in the setting studied. Nonetheless, this gender imbalance should be considered when interpreting the results, particularly in relation to gender-based comparisons. Finally, the small proportion of participants who responded to the question on perceived stressors may limit the ability to draw broader conclusions about the key factors affecting mental health among frontline workers.

7. Conclusions

This study highlighted the need for an adequate mental health support team to ensure mental health wellness during outbreaks, especially among young female hospital workers. While COVID-19 is no longer a significant threat to public health, this study added new knowledge on the mental health aspects of frontline workers during outbreaks and pandemics. Key stressors included concerns about workplace safety, poor work rotation, and lack of mental health support, all significantly associated with higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. These findings underscore the need for targeted mental health support, improved workplace safety protocols, and better work management practices to mitigate the mental health impact on healthcare workers during public health emergencies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.I. and S.S.Y.; data curation, M.Z.M. and M.F.M.; formal analysis, N.M.; investigation, M.Z.M. and M.F.M.; methodology, R.I. and S.S.Y.; resources, M.Z.M. and M.F.M.; validation, N.M.; visualization, M.F.I.; writing—original draft, N.M., R.I., M.F.I., I.H.A.S. and S.S.Y.; writing—review and editing, N.M., R.I., M.F.I., I.H.A.S., M.Z.M., M.F.M. and S.S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, registered with the National Medical Research Registry, Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-20-1485-55191 (IIR)), and received ethical approval from the Medical Research and Ethics Committee, with reference number KKM/NIHSEC/P20-1532(4), 21 July 2022. For confidentiality, anonymous data were obtained from the MHPSS team, without revealing any personal identification. Only the investigators gained access to the dataset to ensure data protection and confidentiality.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and third-party restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article and the Director of the Institute for Medical Research Malaysia for the tremendous support given. We also thank members of the Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Services team from Selangor State Health Department for their cooperation and support during data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| MHPSS | Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Services |

| DASS-21 | Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale 21 |

| MOH | Ministry of Health Malaysia |

References

- Sampath, S.; Khedr, A.; Qamar, S.; Tekin, A.; Singh, R.; Green, R.; Kashyap, R.; Sampath, S.; Khedr, A.; Qamar, S.; et al. Pandemics Throughout the History. Cureus 2021, 13, e18136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatter, K.A.; Finkelman, P. History of the Plague: An Ancient Pandemic for the Age of COVID-19. Am. J. Med. 2021, 134, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio Betancourt, M.; Duarte-Díaz, A.; Vall-Roqué, H.; Seils, L.; Orrego, C.; Perestelo-Pérez, L.; Barrio-Cortes, J.; Beca-Martínez, M.T.; Molina Serrano, A.; Bermejo-Caja, C.J.; et al. Global Healthcare Needs Related to COVID-19: An Evidence Map of the First Year of the Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzek, P.-S.; Jerg-Bretzke, L.; Erim, Y.; Geiser, F.; Beschoner, P. Results of the Voice Study: Stress and Working Conditions in the Health System in a Long-Term Comparison between Occupational Groups. Eur. Psychiatry 2022, 65, S503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerding, T.; Davis, K.G.; Wang, J. An Investigation into Occupational Related Stress of At-Risk Workers During COVID-19. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2023, 67, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; McLoughlin, C.; Stillman, M.; Poplau, S.; Goelz, E.; Taylor, S.; Nankivil, N.; Brown, R.; Linzer, M.; Cappelucci, K.; et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Stress and Burnout among U.S. Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Cross-Sectional Survey Study. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 35, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazi, T.H.; BinDhim, N.F.; Alenazi, M.H.; Tamim, H.; Almagrabi, R.S.; Aljohani, S.M.; Basyouni, M.H.; Almubark, R.A.; Althumiri, N.A.; Alqahtani, S.A. Prevalence and Predictors of Anxiety among Healthcare Workers in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, R.; Socci, V.; Pacitti, F.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Di Marco, A.; Siracusano, A.; Rossi, A. Mental Health Outcomes Among Frontline and Second-Line Health Care Workers During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2010185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.Y.Q.; Chew, N.W.S.; Lee, G.K.H.; Jing, M.; Goh, Y.; Yeo, L.L.L.; Zhang, K.; Chin, H.K.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, F.A.; et al. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Care Workers in Singapore. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendra Kumar, M.K.; Francis, B.; Hashim, A.H.; Zainal, N.Z.; Abdul Rashid, R.; Ng, C.G.; Danaee, M.; Hussain, N.; Sulaiman, A.H. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression among Psychiatric Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Malaysian Perspective. Healthcare 2022, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, N.; Ismail, R.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Abdul Shukor, I.H.; Mohamad, M.Z.; Mahmud, M.F.; Yaacob, S.S. Assessing Mental Health Outcomes in Quarantine Centres: A Cross-Sectional Study during COVID-19 in Malaysia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.; Phan, Y.-H.; Chandriah, K.; Arman, M.R.; Mokhtar, N.N.; Hamdan, S.A.; Yew, S.Q. Insights into Frontline Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health amidst COVID-19—Sources of Workplace Worries and Coping Strategies. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, B.; Rath, S.; Mohanty, M.; Mohapatra, P.R.; Mishra, B.; Rath, S.; Mohanty, M.; Mohapatra, P.R. The Threat of Impending Pandemics: A Proactive Approach. Cureus 2023, 15, e36723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliwichi, L.; Kondowe, F.; Mmanga, C.; Mchenga, M.; Kainja, J.; Nyamali, S.; Ndasauka, Y. The Mental Health Toll among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Malawi. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Statistics Malaysia—The Population of Malaysia|OpenDOSM. Available online: https://open.dosm.gov.my (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Anuar, A.; Mohd Hussain, N.H.; Mohd, T.; Masrom, S.; Ahmad, S. Migration Intentions in Selangor, Malaysia: A Descriptive Analysis; Universiti Teknologi MARA: Cawangan Perak, Malaysian, 2022; pp. 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Malaysia, P.D. Human Resources for Health (HRH) Country Profiles 2019–2021 Malaysia; Ministry of Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2023; ISBN 978-967-25839-3-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rusli, B.N.; Amrina, K.; Trived, S.; Loh, K.P.; Shashi, M. Construct Validity and Internal Consistency Reliability of the Malay Version of the 21-Item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (Malay-DASS-21) among Male Outpatient Clinic Attendees in Johor. Med. J. Malays. 2017, 72, 264–270. [Google Scholar]

- Thiyagarajan, A.; James, T.G.; Marzo, R.R. Psychometric Properties of the 21-Item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) among Malaysians during COVID-19: A Methodological Study. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, R.; Fadzil, M.A.; Zain, Z. Translation, Validation and Psychometric Properties of Bahasa Malaysia Version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS). ASEAN J. Psychiatry 2007, 8, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Isha, A.S.N.; Naji, G.M.A.; Saleem, M.S.; Brough, P.; Alazzani, A.; Ghaleb, E.A.A.; Muneer, A.; Alzoraiki, M. Validation of “Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales” and “Changes in Psychological Distress during COVID-19” among University Students in Malaysia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Warren, N.; Mcmahon, L.; Dalais, C.; Henry, I.; Siskind, D. Occurrence, Prevention, and Management of the Psychological Effects of Emerging Virus Outbreaks on Healthcare Workers: Rapid Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2020, 369, m1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, R.; Tan, H.L.; Oveisi, N.; Memmott, C.; Korzuchowski, A.; Hawkins, K.; Smith, J. Women Healthcare Workers’ Experiences during COVID-19 and Other Crises: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2022, 4, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, J.; Agrawal, A.; Miotto, K. Psychological Distress Among Women Healthcare Workers: A Health System’s Experience Developing Emotional Support Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2021, 2, 614723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Y.; Durand, V.; Morton, K.; Ottolini, M.; Shaughnessy, E.; Spector, N.D.; O’Toole, J. Collateral Damage: How COVID-19 Is Adversely Impacting Women Physicians. J. Hosp. Med. 2020, 15, 507–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czepiel, D.; McCormack, C.; da Silva, A.T.C.; Seblova, D.; Moro, M.F.; Restrepo-Henao, A.; Martínez, A.M.; Afolabi, O.; Alnasser, L.; Alvarado, R.; et al. Inequality on the Frontline: A Multi-Country Study on Gender Differences in Mental Health among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Camb. Prisms Glob. Ment. Health 2024, 11, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biber, J.; Ranes, B.; Lawrence, S.; Malpani, V.; Trinh, T.T.; Cyders, A.; English, S.; Staub, C.L.; McCausland, K.L.; Kosinski, M.; et al. Mental Health Impact on Healthcare Workers Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A U.S. Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2022, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.D.; Amigo, F.; Vilagut, G.; Mortier, P.; Muñoz-Ruiperez, C.; Rodrigo Holgado, I.; Juanes González, A.; Combarro Ripoll, C.E.; Alonso, J.; Rubio, G. Impact of COVID-19 First Wave on the Mental Health of Healthcare Workers in a Front-Line Spanish Tertiary Hospital: Lessons Learned. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch-Vicente, B.; Acosta-Rodriguez, J.M.; Sanchez-Sanchez, M.E.; González-García, N.; Garcia-Ullan, L.L.; de la Iglesia-Larrad, J.I.; Montejo, Á.L.; Roncero, C. Coping Strategies Used by Health-Care Workers during the SARS-CoV2 Crisis. A Real-World Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 317, 114915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, S.H.; Mansoor, H.I.; Alzeyadi, S.; Al-Juboori, A.K.K.; Mahmood, F.M.; Hashim, G.A.; Hashim, G.A. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Occupational Hazard among Nursing Staff at Teaching Hospitals in Kerbala City, South-Central Iraq. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, M.; Bluck, S.; McAdams, D.P. More Vulnerable? The Life Story Approach Highlights Older People’s Potential for Strength During the Pandemic. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2021, 76, e45–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razali, S.; Abdullah, M.N.; Rahman, N.A.; Azhar, N.A.; Yaacob, S.S. Psychological Distress of Health Care Workers in the Main Admitting Hospital and Its Related Health Care Facilities in Malaysia During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Asia. Pac. J. Public Health 2021, 33, 667–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golemis, A.; Voitsidis, P.; Parlapani, E.; Nikopoulou, V.A.; Tsipropoulou, V.; Karamouzi, P.; Giazkoulidou, A.; Dimitriadou, A.; Kafetzopoulou, C.; Holeva, V.; et al. Young Adults’ Coping Strategies against Loneliness during the COVID-19-Related Quarantine in Greece. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daab053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrabissa, G.; Simpson, S.G. Psychological Consequences of Social Isolation During COVID-19 Outbreak. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 571825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, J.H.; Adman, M.A.; Hashim, Z.; Mohd Radi, M.F.; Kwan, S.C. COVID-19 Epidemic in Malaysia: Epidemic Progression, Challenges, and Response. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 560592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gu, W.; Meng, Q. The Impact of COVID-19 on Logistics and Coping Strategies: A Literature Review. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2023, 15, 1768–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, D.B.; Abdul Taib, N.A.; Jing Teo, A.K.; Jayaraj, V.J.; Ting, C.Y. Vaccines Alone Are No Silver Bullets: A Modeling Study on the Impact of Efficient Contact Tracing on COVID-19 Infection and Transmission in Malaysia. Int. Health 2023, 15, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, N.S.; Yusoff, M.S.B.; Asrenee, A.R.; Morgan, K. Burnout Prevalence and Its Associated Factors among Malaysian Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Embedded Mixed-Method Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Durán, E.L.; Fumadó, C.M.; Gassó, A.M.; Díaz, S.; Miranda-Mendizabal, A.; Forero, C.G.; Virumbrales, M. COVID-19 Pandemic Psychological Impact and Volunteering Experience Perceptions of Medical Students after 2 Years. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, T.; Layous, K.; Zhou, X.; Sedikides, C. Distressed but Happy: Health Workers and Volunteers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cult. Brain 2022, 10, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, G.C.; Arip, M.; Saraswathy Subramaniam, T.S. Knowledge and Risk Perceptions of Occupational Infections Among Health-Care Workers in Malaysia. Saf. Health Work 2017, 8, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, F.M.; Owens, J. Factors Associated with Psychological Distress in Health-Care Workers During an Infectious Disease Outbreak: A Rapid Systematic Review of the Evidence. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 589545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablao, J.; Thangam, M.M.N.; Saif, R.; Alamri, R.; Almashhori, W.; Alshehri, R.; Alemrani, S. Shift Work Disorder among Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Rev Rene 2023, 24, e92289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrowes, S.A.B.; Casey, S.M.; Pierre-Joseph, N.; Talbot, S.G.; Hall, T.; Christian-Brathwaite, N.; Del-Carmen, M.; Garofalo, C.; Lundberg, B.; Mehta, P.K.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts on Mental Health, Burnout, and Longevity in the Workplace among Healthcare Workers: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2023, 32, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripoll, J.; Chela, X.; Briones-VozmedianoFiol-de Roque, E.M.A.; Zamanillo-Campos, R.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Llobera, J.; Calafat-Villalonga, C.; Serrano-Ripoll, M.J. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health of Health Care Workers in Spain: A Mix-Methods Study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobnik, M.; Lorber, M. Management Support for Healthcare Workers’ Mental Health and Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cohort Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styra, R.; Hawryluck, L.; McGeer, A.; Dimas, M.; Lam, E.; Giacobbe, P.; Lorello, G.; Dattani, N.; Sheen, J.; Rac, V.E.; et al. Support for Health Care Workers and Psychological Distress: Thinking about Now and beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2022, 42, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).