Looking Back After the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Parents’ View on Screen Media Use, Psychopathology, and Psychological Burden in a Clinical Sample of Children and Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Impact of the Pandemic on Children’s and Adolescents’ Mental Health

1.2. Impact of the Pandemic on Screen Media Use in Children and Adolescents

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment

2.2. Context

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Distribution of Psychopathological Problems

3.3. State of Mental Health Before and During the Pandemic

3.4. Impact of the Pandemic on the Severity of the Main and Secondary Mental Problems

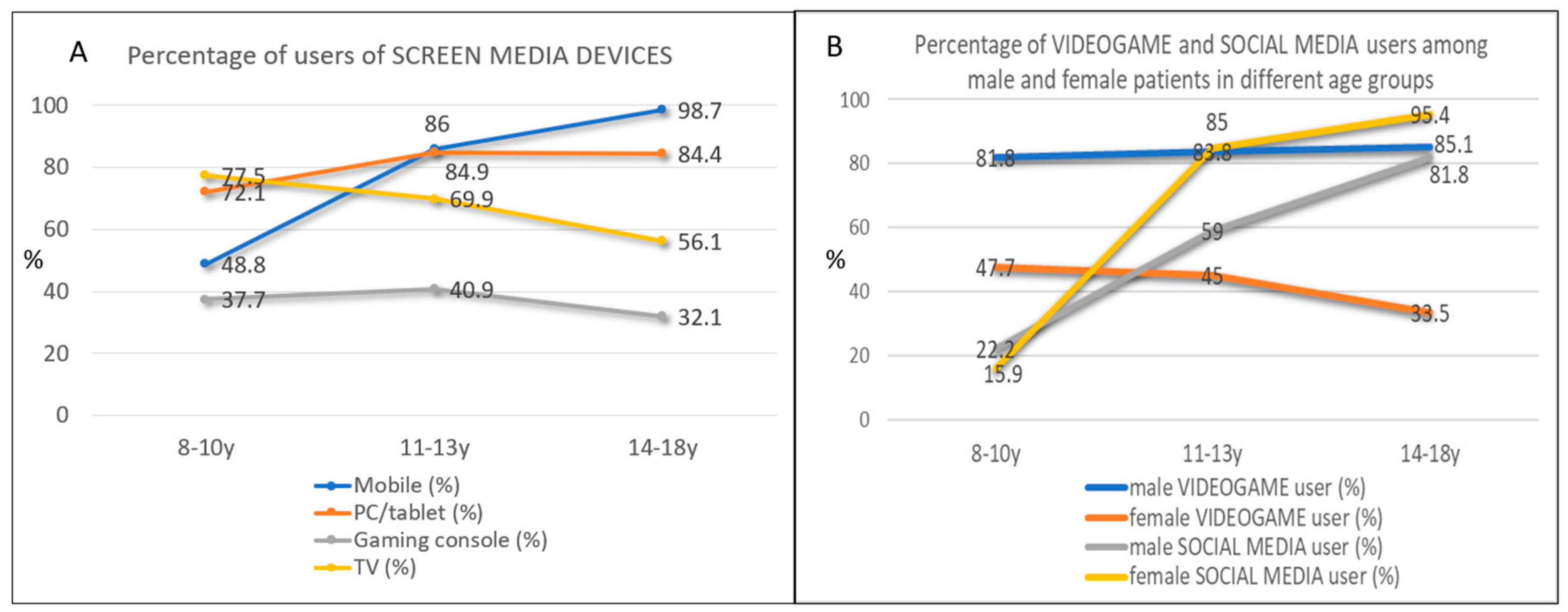

3.5. Screen Media Use

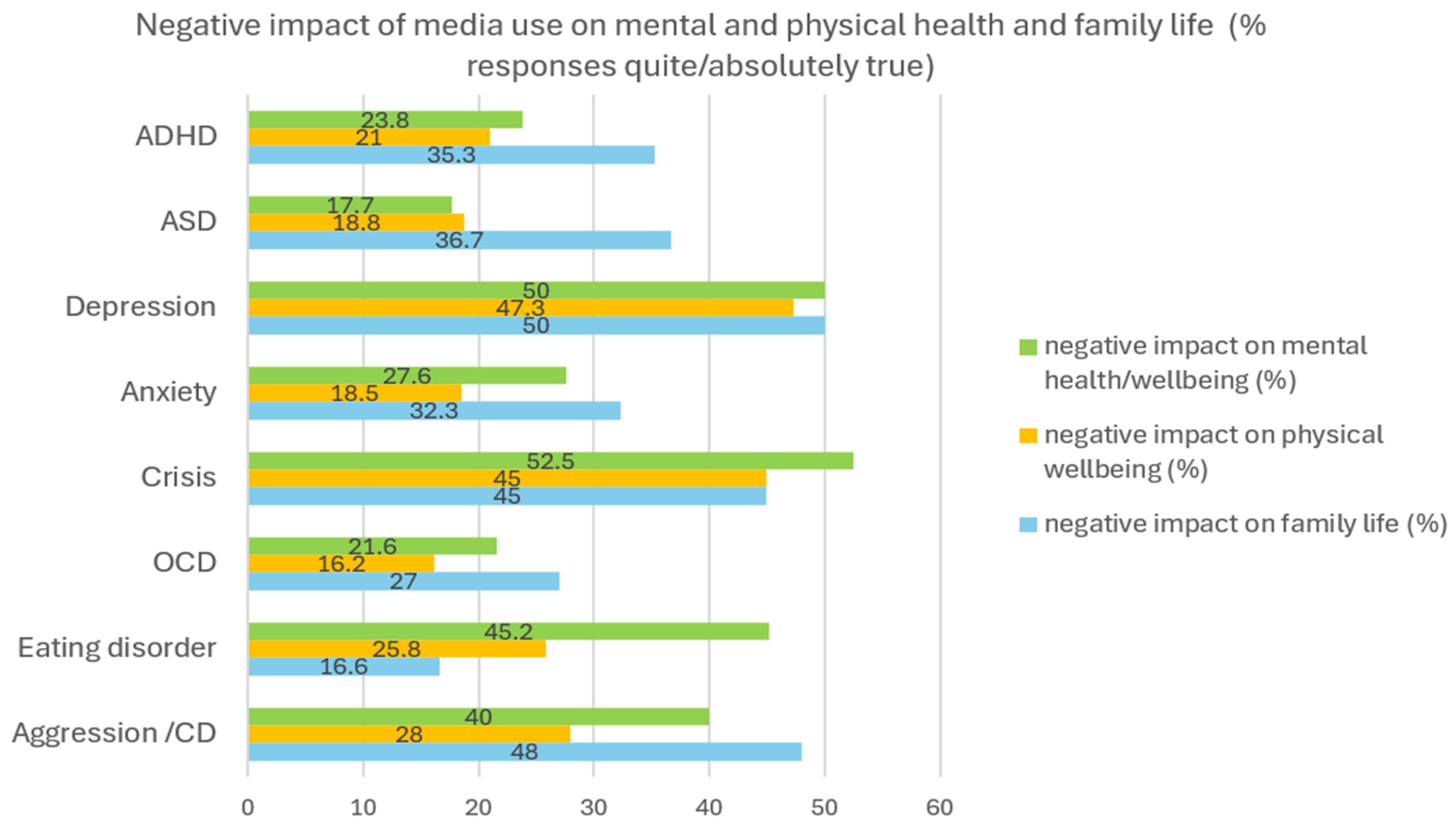

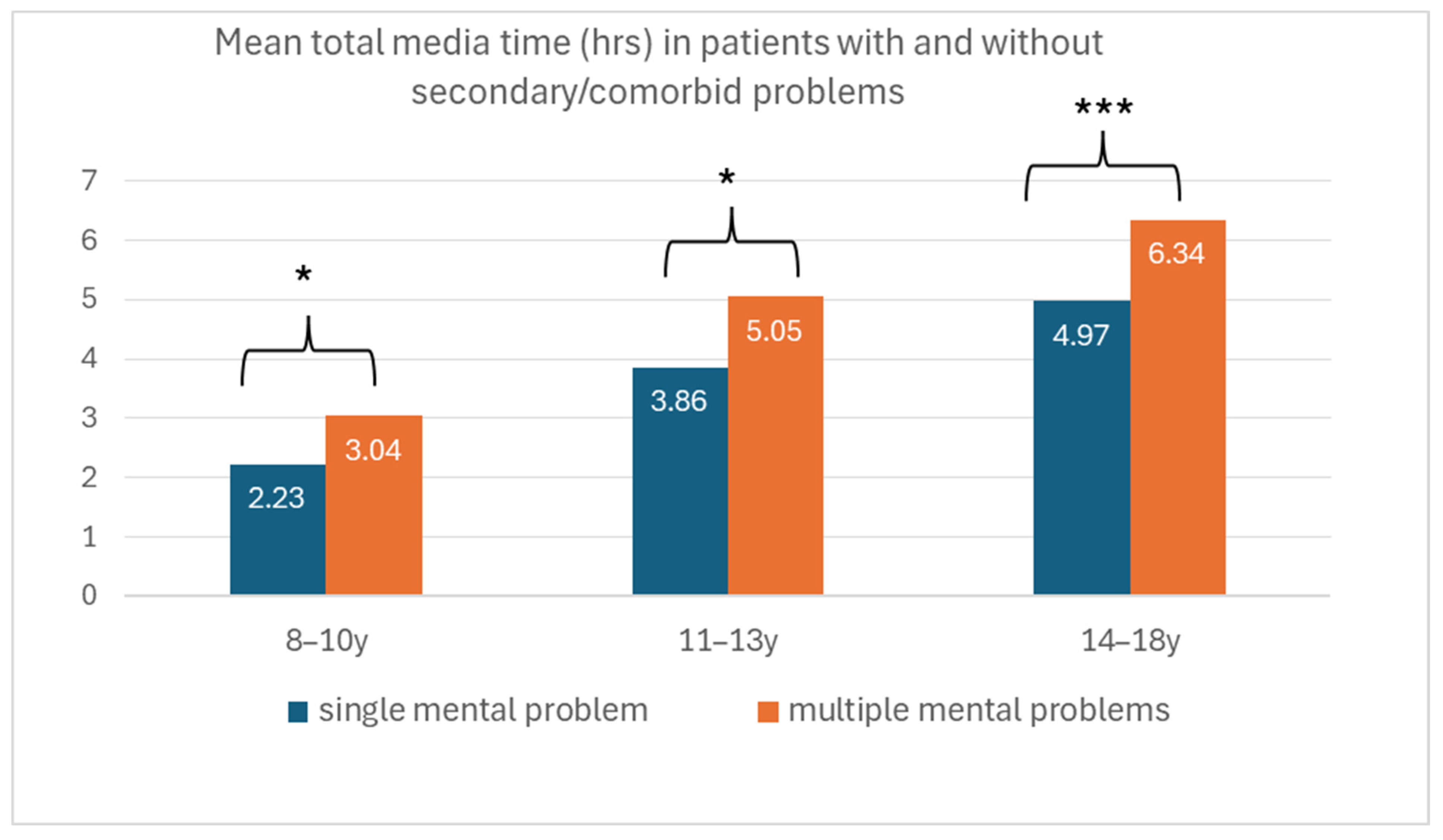

3.6. Association Between Mental Health and Screen Media Use

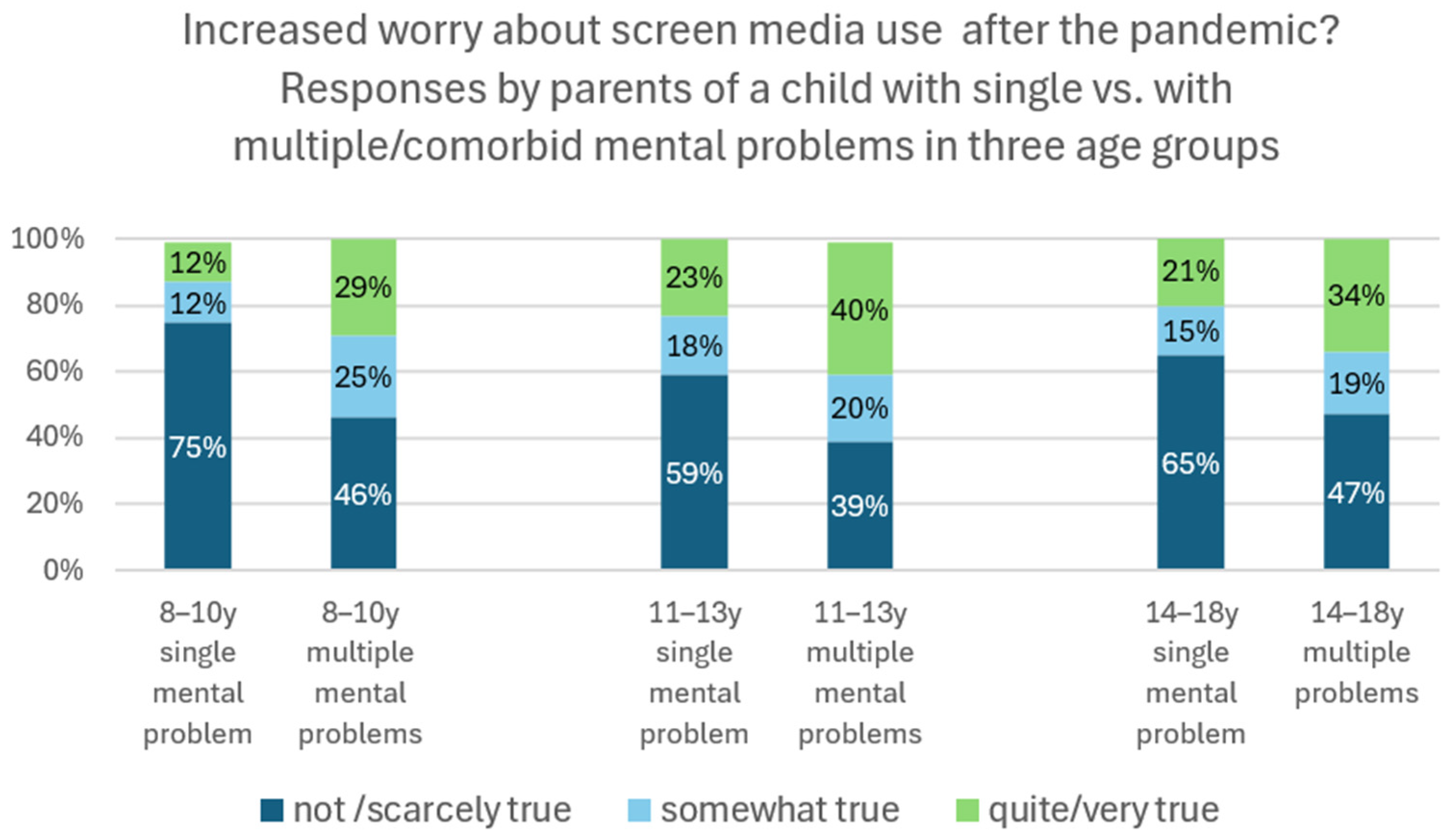

3.7. Impact of the Pandemic on Screen Media Use

| Feeling Quite/Heavily Burdened | Particularly High Media Use | Particularly High Symptom Severity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lockdown | 48.9% | 53% | 26.5% |

| Summer 2020 | 25.5% | 16% | 13.3% |

| Autumn 2020 (second wave) | 42.3% | 34% | 18.4% |

| Winter 2021 | 40.2% | 46% | 16.9% |

| Last 2 weeks (Spring 2021) | 18.3% | 14% | 4.4% |

| Never high/unchanged | - | 16% | 31.2% |

3.8. Looking Back After the First Year of the COVID-19 Crisis

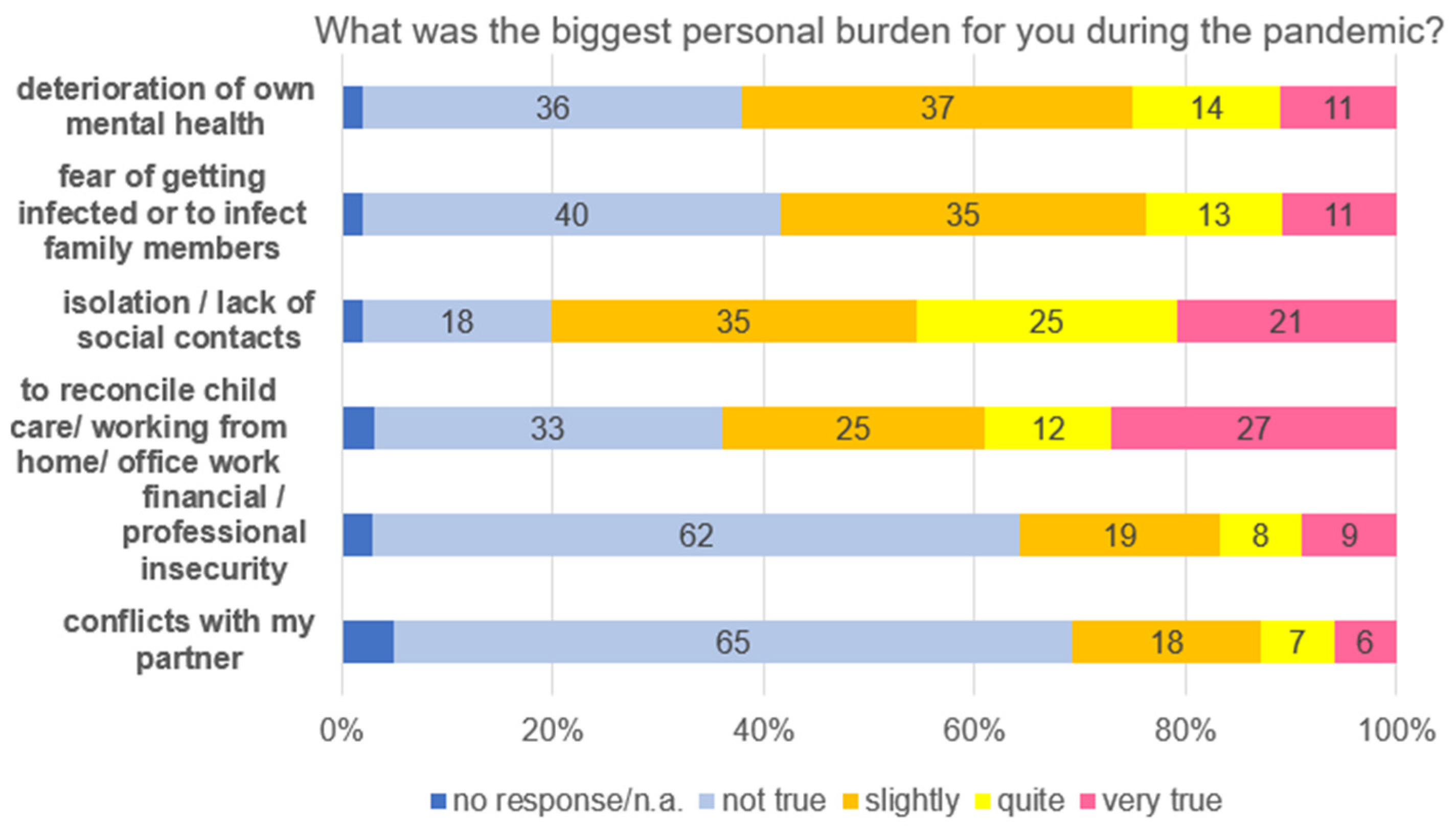

3.9. The Most Serious Burdens from a Parent’s Perspective

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of the Pandemic on Mental Problems

4.2. Screen Media Use and Its Relation to Mental Health During the Pandemic

4.3. Retrospective View on Time Periods and Personal Burdens

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Green, K.H.; van de Groep, S.; Sweijen, S.W.; Becht, A.I.; Buijzen, M.; de Leeuw, R.N.H.; Remmerswaal, D.; van der Zanden, R.; Engels, R.C.M.E.; Crone, E.A. Mood and Emotional Reactivity of Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Short-Term and Long-Term Effects and the Impact of Social and Socioeconomic Stressors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.A.; Ford, T.; Everall, I.; Silver, R.; Christensen, H.; Ballard, C.; Arseneault, L.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary Research Priorities for the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Call for Action for Mental Health Science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 6, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Mental Health Effects of School Closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, Z. Perceived Stress of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Adolescents’ Depression Symptoms: The Moderating Role of Character Strengths. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 182, 111062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Dosil-Santamaria, M.; Picaza-Gorrochategui, M.; Idoiaga-Mondragon, N. Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Levels in the Initial Stage of the COVID-19 Outbreak in a Population Sample in the Northern Spain. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00054020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacio-Ortiz, J.D.; Londoño-Herrera, J.P.; Nanclares-Márquez, A.; Robledo-Rengifo, P.; Quintero-Cadavid, C.P. Psychiatric Disorders in Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2020, 49, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tso, W.W.Y.; Wong, R.S.; Tung, K.T.S.; Rao, N.; Fu, K.W.; Yam, J.C.S.; Chua, G.T.; Chen, E.Y.H.; Lee, T.M.C.; Chan, S.K.W.; et al. Vulnerability and Resilience in Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, P.K.; Gupta, J.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Kumar, R.; Meena, A.K.; Madaan, P.; Sharawat, I.K.; Gulati, S. Psychological and Behavioral Impact of Lockdown and Quarantine Measures for COVID-19 Pandemic on Children, Adolescents and Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2021, 67, fmaa122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegert, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P.L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and Burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic for Child and Adolescent Mental Health: A Narrative Review to Highlight Clinical and Research Needs in the Acute Phase and the Long Return to Normality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques de Miranda, D.; da Silva Athanasio, B.; Sena Oliveira, A.C.; Simoes-e-Silva, A.C. How Is COVID-19 Pandemic Impacting Mental Health of Children and Adolescents? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Mann, S.; Singh, R.; Bangar, R.; Kulkarni, R. Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents. Cureus 2020, 12, e10051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, D.; Angelo Fabris, M.; Longobardi, C.; Settanni, M. Smartphone and Social Media Use Contributed to Individual Tendencies towards Social Media Addiction in Italian Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Addict. Behav. 2022, 126, 107204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Rosendahl, I.; Jayaram-Lindström, N. Gaming and Social Media Use among Adolescents in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic. NAD Nord. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2022, 39, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuszczki, E.; Bartosiewicz, A.; Pezdan-śliż, I.; Kuchciak, M.; Jagielski, P.; Oleksy, Ł.; Stolarczyk, A.; Dereń, K. Children’s Eating Habits, Physical Activity, Sleep, and Media Usage before and during COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschke, K.; Austermann, M.I.; Simon-Kutscher, K.; Thomasius, R. Adolescent Gaming and Social Media Usage before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sucht 2021, 67, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Kaman, A.; Otto, C.; Adedeji, A.; Napp, A.-K.; Becker, M.; Blanck-Stellmacher, U.; Löffler, C.; Schlack, R.; Hölling, H.; et al. Seelische Gesundheit Und Psychische Belastungen von Kindern Und Jugendlichen in Der Ersten Welle Der COVID-19-Pandemie—Ergebnisse Der COPSY-Studie. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2021, 64, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werling, A.M.; Walitza, S.; Drechsler, R. Impact of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Screen Media Use in Patients Referred for ADHD to Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: An Introduction to Problematic Use of the Internet in ADHD and Results of a Survey. J. Neural Transm. 2021, 128, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werling, A.M.; Walitza, S.; Grünblatt, E.; Drechsler, R. Media Use before, during and after COVID-19 Lockdown According to Parents in a Clinically Referred Sample in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Results of an Online Survey in Switzerland. Compr. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 152260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werling, A.M.; Walitza, S.; Gerstenberg, M.; Grünblatt, E.; Drechsler, R. Media Use and Emotional Distress under COVID-19 Lockdown in a Clinical Sample Referred for Internalizing Disorders: A Swiss Adolescents’ Perspective. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 147, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Xue, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, K.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Song, R. Mental Health Status among Children in Home Confinement during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 898–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, N.; McArthur, B.A.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Zhu, J.; Madigan, S. Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents during COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.J.; Zhang, L.G.; Wang, L.L.; Guo, Z.C.; Wang, J.Q.; Chen, J.C.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.X. Prevalence and Socio-Demographic Correlates of Psychological Health Problems in Chinese Adolescents during the Outbreak of COVID-19. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, J.; Kohls, E.; Moessner, M.; Lustig, S.; Bauer, S.; Becker, K.; Thomasius, R.; Eschenbeck, H.; Diestelkamp, S.; Gillé, V.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 Related Lockdown Measures on Self-Reported Psychopathology and Health-Related Quality of Life in German Adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vira, E.G.; Skoog, T. Swedish Middle School Students’ Psychosocial Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Study. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussières, E.L.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Meilleur, A.; Mastine, T.; Hérault, E.; Chadi, N.; Montreuil, M.; Généreux, M.; Camden, C.; Roberge, P.; et al. Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 691659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlack, R.; Neuperdt, L.; Junker, S.; Eicher, S.; Hölling, H.; Thom, J.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Beyer, A.-K. Changes in Mental Health in the German Child and Adolescent Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Results of a Rapid Review. J. Health Monit. 2023, 8, 2–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, K.; Schmitz, J. Scoping Review: Longitudinal Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 1257–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig-Walz, H.; Dannheim, I.; Pfadenhauer, L.M.; Fegert, J.M.; Bujard, M. Increase of Depression among Children and Adolescents after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.L.; Clark, C.A.; Bagshawe, M.; Kuntz, J.; Perri, A.; Deegan, A.; Marriott, B.; Rahman, A.; Graham, S.; McMorris, C.A. A Comparison of Psychiatric Inpatient Admissions in Youth before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park, J.L.; McArthur, B.A.; Plamondon, A.; Hewitt, J.M.A.; Racine, N.; McDonald, S.; Tough, S.; Madigan, S. The Course of Children’s Mental Health Symptoms during and beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 3345–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prati, G.; Mancini, A.D. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdowns: A Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies and Natural Experiments. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zijlmans, J.; Tieskens, J.M.; van Oers, H.A.; Alrouh, H.; Luijten, M.A.J.; de Groot, R.; van der Doelen, D.; Klip, H.; van der Lans, R.M.; de Meyer, R.; et al. The Effects of COVID-19 on Child Mental Health: Biannual Assessments up to April 2022 in a Clinical and Two General Population Samples. JCPP Adv. 2023, 3, e12150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Thompson, T.; Cortese, S.; Estradé, A.; Agorastos, A.; Radua, J.; Dragioti, E.; Vancampfort, D.; Thygesen, L.C.; Aschauer, H.; et al. Collaborative Outcomes Study on Health and Functioning During Infection Times (COH-FIT): Global and Risk-Group Stratified Course of Well-Being and Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Adolescents. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2025, 64, 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.; Estévez-Lamorte, N.; Walitza, S.; Dzemaili, S.; Mohler-Kuo, M. Perceived Stress, Coping Strategies, and Mental Health Status among Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Switzerland: A Longitudinal Study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaman, A.; Devine, J.; Wirtz, M.A.; Erhart, M.; Boecker, M.; Napp, A.K.; Reiss, F.; Zoellner, F.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Trajectories of Mental Health in Children and Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from the Longitudinal COPSY Study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2024, 18, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Jin, H. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 340, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.; Russell, S.; Saulle, R.; Croker, H.; Stansfield, C.; Packer, J.; Nicholls, D.; Goddings, A.L.; Bonell, C.; Hudson, L.; et al. School Closures during Social Lockdown and Mental Health, Health Behaviors, and Well-Being among Children and Adolescents during the First COVID-19 Wave: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulle, R.; De Sario, M.; Bena, A.; Capra, P.; Culasso, M.; Davoli, M.; De Lorenzo, A.; Lattke, L.S.; Marra, M.; Mitrova, Z.; et al. School Closures and Mental Health, Wellbeing and Health Behaviours among Children and Adolescents during the Second COVID-19 Wave: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Epidemiol. Prev. 2022, 46, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werling, A.M.; Walitza, S.; Eliez, S.; Drechsler, R. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health Care of Children and Adolescents in Switzerland: Results of a Survey among Mental Health Care Professionals after One Year of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werling, A.M.; Walitza, S.; Eliez, S.; Drechsler, R. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health and Family Situation of Clinically Referred Children and Adolescents in Switzerland: Results of a Survey among Mental Health Care Professionals after 1 Year of COVID-19. J. Neural Transm. 2022, 129, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, G.; Häberling, I.; Lustenberger, A.; Probst, F.; Franscini, M.; Pauli, D.; Walitza, S. The Mental Distress of Our Youth in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2022, 152, w30142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revet, A.; Hebebrand, J.; Anagnostopoulos, D.; Kehoe, L.A.; Gradl-Dietsch, G.; Anderluh, M.; Armando, M.; Askenazy, F.; Banaschewski, T.; Bender, S.; et al. Perceived Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Services after 1 Year (February/March 2021): ESCAP CovCAP Survey. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Keown-Stoneman, C.D.G.; Cost, K.T.; Charach, A.; Maguire, J.L.; Monga, S.; Crosbie, J.; Burton, C.; Anagnostou, E.; et al. Screen Use and Mental Health Symptoms in Canadian Children and Youth during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2140875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouter, D.C.; Zarchev, M.; de Neve-Enthoven, N.G.M.; Ravensbergen, S.J.; Kamperman, A.M.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G.; Grootendorst-van Mil, N.H. A Longitudinal Study of Mental Health in At-Risk Adolescents before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilsbach, S.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Konrad, K. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Adolescents With and Without Mental Disorders. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 679041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döpfner, M.; Adam, J.; Habbel, C.; Schulte, B.; Schulze-Husmann, K.; Simons, M.; Heuer, F.; Wegner, C.; Bender, S. Die Psychische Belastung von Kindern, Jugendlichen Und Ihren Familien Während Der COVID-19-Pandemie Und Der Zusammenhang Mit Emotionalen Und Verhaltensauffälligkeiten. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2021, 64, 1522–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melegari, M.G.; Giallonardo, M.; Sacco, R.; Marcucci, L.; Orecchio, S.; Bruni, O. Identifying the Impact of the Confinement of COVID-19 on Emotional-Mood and Behavioural Dimensions in Children and Adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Psychiatry Res. 2021, 296, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo, E.; Lin, L.; Acquaviva, E.; Caci, H.; Franc, N.; Gamon, L.; Picot, M.C.; Pupier, F.; Speranza, M.; Falissard, B.; et al. How Do Children and Adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Experience Lockdown during the COVID-19 Outbreak? Encephale 2020, 46, S85–S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cost, K.T.; Crosbie, J.; Anagnostou, E.; Birken, C.S.; Charach, A.; Monga, S.; Kelley, E.; Nicolson, R.; Maguire, J.L.; Burton, C.L.; et al. Mostly Worse, Occasionally Better: Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Canadian Children and Adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyworth, M.; Brett, S.; Houting, J.d.; Magiati, I.; Steward, R.; Urbanowicz, A.; Stears, M.; Pellicano, E. “It Just Fits My Needs Better”: Autistic Students and Parents’ Experiences of Learning from Home during the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2021, 6, 23969415211057681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Su, Y.; Sun, P.; Liu, M. Latent Patterns of Depression Trajectory among Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 324, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlatini, V.; Frangou, L.; Zhang, S.; Epstein, S.; Morris, A.; Grant, C.; Zalewski, L.; Jewell, A.; Velupillai, S.; Simonoff, E.; et al. Emotional and Behavioral Outcomes among Youths with Mental Disorders during the First Covid Lockdown and School Closures in England: A Large Clinical Population Study Using Health Care Record Integrated Surveys. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 59, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Hanif, A.; Khaliq, I.; Ayub, S.; Saboor, S.; Shoib, S.; Jawad, M.Y.; Arain, F.; Anwar, A.; Ullah, I.; et al. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder—A Literature Review. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2024, 70, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessain, A.; Parlatini, V.; Singh, A.; De Bruin, M.; Cortese, S.; Sonuga-Barke, E.; Serrano, J.V. Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children and Adolescents with ADHD: A Systematic Review of Controlled Longitudinal Cohort Studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 156, 105502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzman, D.K.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Vyver, E.; Singh, M.; Austin, A.; Marcoux-Louie, G.; Patten, S.B. Hospitalizations for Eating Disorders and Other Mental, Behavioral, and Neurodevelopmental Disorders Before and During COVID-19 in Canada. J. Adolesc. Health 2025, 76, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccari, V.; D’Arienzo, M.C.; Caiazzo, T.; Magno, A.; Amico, G.; Mancini, F. Narrative Review of COVID-19 Impact on Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Child, Adolescent and Adult Clinical Populations. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 673161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohler-Kuo, M.; Dzemaili, S.; Foster, S.; Werlen, L.; Walitza, S. Stress and Mental Health among Children/Adolescents, Their Parents, and Young Adults during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in Switzerland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Ren, Q.; Zhong, N.; Bao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Du, J.; Chen, T.; Zhao, M. Internet Behavior Patterns of Adolescents before, during, and after COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 947360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.; Xiang, G.X.; Li, M.; Jin, X.; Qin, K.N. Positive Youth Development Attributes, Mental Disorder, and Problematic Online Behaviors in Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1133696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutley, S.B.; Burén, J.; Thorell, L.B. COVID-19 Restrictions Resulted in Both Positive and Negative Effects on Digital Media Use, Mental Health, and Lifestyle Habits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, E.; Ji, X.R.; Alkawaja, M.; Molyneux, T.M.; Kerai, S.; Thomson, K.C.; Guhn, M.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Gadermann, A.M. Connections Matter: Adolescent Social Connectedness Profiles and Mental Well-Being over Time. J. Adolesc. 2024, 96, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putra, P.Y.; Fithriyah, I.; Zahra, Z. Internet Addiction and Online Gaming Disorder in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Psychiatry Investig. 2023, 20, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, M.; Khoshgoftar, M.; Jadidi, H.; Daniali, S.S.; Kelishadi, R. Screen Time and Child Behavioral Disorders During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansner, M.; Nisenson, M.; Lin, V.; Pong, S.; Torous, J.; Carson, N. Problematic Internet Use before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Youth in Outpatient Mental Health Treatment: App-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2022, 9, e33114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, F.W.; Joas, J.; Gerstner, I.; Kühn, A.; Wenning, M.; Gehrke, T.; Burckhart, H.; Richter, U.; Nonnenmacher, A.; Zemlin, M.; et al. Problematic Internet Use among Adolescents 18 Months after the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Children 2022, 9, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouleau, R.D.; Beauregard, C.; Beaudry, V. A Rise in Social Media Use in Adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The French Validation of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale in a Canadian Cohort. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fineberg, N.A.; Menchón, J.M.; Hall, N.; Dell’Osso, B.; Brand, M.; Potenza, M.N.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Cirnigliaro, G.; Lochner, C.; Billieux, J.; et al. Advances in Problematic Usage of the Internet Research—A Narrative Review by Experts from the European Network for Problematic Usage of the Internet. Compr. Psychiatry 2022, 118, 152346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunney, C.; Rooney, B. Using Theoretical Models of Problematic Internet Use to Inform Psychological Formulation: A Systematic Scoping Review. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 810–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano, L.; Ostroumova, M.; Schulz, P.J.; Camerini, A.L. Digital Media Use and Adolescents’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 793868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiguna, T.; Minayati, K.; Kaligis, F.; Teh, S.D.; Sourander, A.; Dirjayanto, V.J.; Krishnandita, M.; Meriem, N.; Gilbert, S. The Influence of Screen Time on Behaviour and Emotional Problems among Adolescents: A Comparison Study of the Pre-, Peak, and Post-Peak Periods of COVID-19. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldorsdottir, T.; Thorisdottir, I.E.; Meyers, C.C.A.; Asgeirsdottir, B.B.; Kristjansson, A.L.; Valdimarsdottir, H.B.; Allegrante, J.P.; Sigfusdottir, I.D. Adolescent Well-Being amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Are Girls Struggling More than Boys? JCPP Adv. 2021, 1, e12027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidis, A.; Paksarian, D.; Alexander, L.; Derosa, J.; Dunn, J.; Nielson, D.M.; Droney, I.; Kang, M.; Douka, I.; Bromet, E.; et al. The Coronavirus Health and Impact Survey (CRISIS) Reveals Reproducible Correlates of Pandemic-Related Mood States across the Atlantic. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, N.; Hill, J.; Sharp, H.; Refberg-Brown, M.; Crook, D.; Kehl, S.; Pickles, A. COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Adolescent Mental Health: A Reassessment Accounting for Development. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 2615–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Bang, Y.R.; Kim, C.K. Sex and Age Differences in Psychiatric Disorders among Children and Adolescents: High-Risk Students Study. Psychiatry Investig. 2014, 11, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luginaah, N.A.; Batung, E.S.; Ziegler, B.R.; Amoak, D.; Trudell, J.P.; Arku, G.; Luginaah, I. The Parallel Pandemic: A Systematic Review on the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on OCD among Children and Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanir, Y.; Karayagmurlu, A.; Kaya, İ.; Kaynar, T.B.; Türkmen, G.; Dambasan, B.N.; Meral, Y.; Coşkun, M. Exacerbation of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Symptoms in Children and Adolescents during COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, K.J.; Michelson, D. Perfect Storm: Emotionally Based School Avoidance in the Post-COVID-19 Pandemic Context. BMJ Ment. Health 2024, 27, e300944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werling, A.; Drechsler, R.; Walitza, S.; Musliu, L.; Bachmann, S.; Moser, K.; Mohler-Kuo, M. Pro Juventute Jugendstudie. Umgang mit Stress, Krisen, Mediennutzung und Resilienz bei Jugendlichen und Jungen Erwachsenen in der Schweiz. 2024. Available online: https://www.projuventute.ch/sites/default/files/2024-11/09112024_dt_pro_juventute_jugendstudie_2024.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Becker, T.D.; Leong, A.; Shanker, P.; Martin, D.; Staudenmaier, P.; Lynch, S.; Rice, T.R. Digital Media-Related Problems Contributing to Psychiatric Hospitalizations Among Children and Adolescents Before and After the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Centeno, C.; Cueto-Galán, R.; Pena-Andreu, J.M.; Fontalba-Navas, A. Problematic Internet Use and Its Relationship with Eating Disorders. Front. Public Health 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas Brandão, L.; Sanchez, Z.M.; Patricia, P.P.; da Silva Melo, M.H. Mental Health and Behavioral Problems Associated with Video Game Playing among Brazilian Adolescents. J. Addict. Dis. 2022, 40, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werling, A.M.; Kuzhippallil, S.; Emery, S.; Walitza, S.; Drechsler, R. Problematic Use of Digital Media in Children and Adolescents with a Diagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Compared to Controls. A Meta-Analysis. J. Behav. Addict. 2022, 11, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, M.; Riedl, D.; Bock, A.; Rumpold, G.; Sevecke, K. Pathological Internet Use—An Important Comorbidity in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Prevalence and Correlation Patterns in a Naturalistic Sample of Adolescent Inpatients. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1629147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal-Pai, J.; Soares, C.B.; de Fraga, V.C.; Porto, A.; Foerster, G.P.; Nunes, M.L. Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children and Adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder—A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. 2024, 100, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Goldenberg, A.; Dorison, C.A.; Miller, J.K.; Uusberg, A.; Lerner, J.S.; Gross, J.J.; Agesin, B.B.; Bernardo, M.; Campos, O.; et al. A Multi-Country Test of Brief Reappraisal Interventions on Emotions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 1089–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, N.M.; Choudhari, S.G.; Gaidhane, A.M.; Quazi Syed, Z. ‘Digital Wellbeing’: The Need of the Hour in Today’s Digitalized and Technology Driven World! Cureus 2022, 14, e27743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanden Abeele, M.M.P. Digital Wellbeing as a Dynamic Construct. Commun. Theory 2021, 31, 932–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | Age Mean (SD) | Patients with a Secondary Problem (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 342 | 49.9% | 13.1 | (2.85) | 56.4% |

| Male 8–10 y | 83 | 12.1% | 9.4 | (0.76) | 47.0% |

| Male 11–13 y | 105 | 15.3% | 12.0 | (0.80) | 55.2% |

| Male 14–18 y | 154 | 22.4% | 15.8 | (1.26) | 62.3% |

| Female | 321 | 46.8% | 13.9 | (2.70) | 57.9% |

| Female 8–10 y | 44 | 6.4% | 9.1 | (0.76) | 38.6% |

| Female 11–13 y | 80 | 11.7% | 12.0 | (0.83) | 56.2% |

| Female 14–18 y | 197 | 28.7% | 15.8 | (1.16) | 62.9% |

| Other/diverse | 23 | 3.4% | 15.2 | (2.6) | 69.6% |

| All | 686 | 100% | 13.5 | (2.81) | 58.0% |

| 8–10 y | 129 | 18.8% | 9.3 | (0.78) | 43.4% |

| 11–13 y | 186 | 27.1% | 12.0 | (0.83) | 55.9% |

| 14–18 y | 371 | 54.1% | 15.8 | (1.20) | 53.3% |

| Main Mental Health Problem over First Year of Pandemic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deteriorated | Unchanged | Improved | No Answer/n.a. | |

| Male (N = 342) | 22.8% | 38.0% | 22.3% | 17% |

| 8–10 y (N = 83) | 18.1% | 34.9% | 28.9% | 18% |

| 11–13 y (N = 105) | 21.9% | 42.9% | 19.0% | 16.2% |

| 14–18 y (N = 154) | 26.0% | 36.4% | 20.8% | 17.8% |

| Female (N = 321) | 34.9% | 22.7% | 18.4% | 23.6% |

| 8–10 y (N = 44) | 22.7% | 31.8% | 29.5% | 15.9% |

| 11–13 y (N = 80) | 35.0% | 27.5% | 18.8% | 18.8% |

| 14–18 y (N = 197) | 37.6% | 18.8% | 15.7% | 28% |

| Gender dysphoria (N = 23) | 21.7% | 34.8% | 21.7% | 21.7% |

| All (N = 686) | 28.4% | 30.8% | 20.4% | 20.4% |

| Main Mental Problem | Change in Severity During Pandemic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Worse | Same | Improved | |

| ADHD | 162 | 28.4% | 47.5% | 24.1% |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 79 | 29.1% | 48.1% | 22.8% |

| Depression | 55 | 58.2% | 18.2% | 23.6% |

| Anxiety | 52 | 28.8% | 34.6% | 36.5% |

| OCD | 32 | 46.9% | 25.0% | 28.1% |

| Acute crisis | 23 | 56.5% | 17.4% | 26.1% |

| Gender dysphoria | 18 | 27.8% | 44.4% | 27.8% |

| Eating disorder | 14 | 57.1% | 28.6% | 14.3% |

| Aggression/CD | 21 | 33.3% | 23.8% | 42.9% |

| Other | 66 | 31.8% | 42.1% | 25.8% |

| Not specified | 24 | 41.7% | 45.8% | 12.5% |

| All | 546 | 37.7% | 38.6% | 25.6% |

| Secondary mental problem | Change in severity during pandemic | |||

| N | Worse | Same | Improved | |

| ADHD | 51 | 41.2% | 51.0% | 7.8% |

| Anxiety | 64 | 46.9% | 32.8% | 20.3% |

| Depression | 73 | 50.7% | 26.0% | 23.3% |

| Absenteeism/withdrawal | 37 | 67.6% | 21.6% | 10.8% |

| OCD | 37 | 40.5% | 40.5% | 18.9% |

| Learning disorder | 40 | 15.0% | 60.0% | 25.0% |

| PUI | 25 | 76.0% | 20.0% | 4.0% |

| Eating disorder | 16 | 68.8% | 18.8% | 12.5% |

| Other | 23 | 52.2% | 43.5% | 4.3% |

| All | 366 | 48.1% | 35.8% | 16.1% |

| Mobile | PC/Tablet | Gaming Console | TV | Total Screen Media Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Time (h) Mean (SD) | Time (h) Mean (SD) | Time (h) Mean (SD) | Time (h) Mean (SD) | Time (h) Mean (SD) | |

| 8–10 y all | 129 | 0.66 (1.10) | 0.82 (1.11) | 0.37 (0.65) | 0.74 (0.88) | 2.58 (2.12) |

| Boys 8–10 y | 83 | 0.74 (1.24) | 0.83 (1.19) | 0.45 (0.70) | 0.78 (0.72) | 2.80 (2.36) |

| Girls 8–10 y | 44 | 0.52 (0.78) | 0.80 (0.94) | 0.24 (0.52) | 0.68 (0.70) | 2.25 (1.58) |

| 11–13 y all | 186 | 1.76 (1.80) | 1.37 (1.49) | 0.61 (1.28) | 0.79 (1.0) | 4.52 (3.59) |

| Male 11–13 y | 105 | 1.56 (1.73) | 1.40 (1.51) | 0.86 (1.41) | 0.79 (1.15) | 4.62 (3.83) |

| Female 11–13 y | 80 | 2.0 (1.87) | 1.26 (1.46) | 0.27 (0.88) | 0.78 (0.78) | 4.33 (3.23) |

| 14–18 y all | 371 | 3.23 (2.07) | 1.54 (1.68) | 0.45 (0.95) | 0.60 (0.86) | 5.83 (3.38) |

| Male 14–18 y | 157 | 2.84 (1.97) | 1.79 (1.94) | 0.76 (1.13) | 0.53 (0.72) | 5.94 (3.40) |

| Female 14–18 y | 197 | 3.49 (2.11) | 1.35 (1.42) | 0.20 (0.70) | 0.65 (0.96) | 5.70 (3.39) |

| All | 686 | 2.35 (2.10) | 1.36 (1.55) | 0.48 (1.01) | 0.68 (0.88) | 4.81 (3.46) |

| Male all | 342 | 1.94 (1.94) | 1.44 (1.69) | 0.72 (1.17) | 0.67 (0.88) | 4.77 (3.54) |

| Female all | 321 | 2.71 (2.20) | 1.26 (1.38) | 0.23 (0.73) | 0.69 (0.88) | 4.88 (3.37) |

| Diverse | 23 | 3.41 (2.04) | 1.54 (1.83) | 0.52 (1.13) | 0.58 (1.11) | 6.06 (2.12) |

| Worry About Screen Media Time I Am Worried About the Amount of Time Spent by My Child… | Percent of Responses (%) | |||

| Not True | Slightly True | Quite True | Absolutely True | |

| … on his/her smartphone | 23.0 | 32.2 | 29.2 | 15.6 |

| … on the internet | 21.4 | 37.5 | 27.0 | 14.1 |

| … playing videogames | 41.1 | 29.7 | 16.3 | 16.3 |

| … on social networks | 38.9 | 29.6 | 17.8 | 13.7 |

| … watching TV | 65.0 | 24.5 | 8.0 | 2.5 |

| Negative Impact on Everyday Life Negative impact of my child’s media use on… | Not True | Slightly True | Quite True | Absolutely True |

| … family life | 24.6 | 40.4 | 23.8 | 11.2 |

| … homework and academic achievements | 38.9 | 37.3 | 16.6 | 7.1 |

| … friendships and social activities in real life | 42.9 | 34.3 | 16.2 | 6.7 |

| … mental well-being and mental health (e.g., mood) | 32.4 | 38.0 | 21.7 | 7.9 |

| … physical well-being and health (e.g., sleep) | 35.7 | 38.8 | 17.8 | 7.7 |

| I am concerned because my child … | ||||

| … becomes aggressive/very angry when media use is restricted | 33.7 | 30.2 | 20.3 | 15.9 |

| … secretly spends more time on media than agreed upon (a) | 35.3 | 28.3 | 14.7 | 13.3 |

| Risky/problem behaviors I am concerned that my child might… | Not True | Slightly True | Quite True | Absolutely True |

| … be a victim of cyberbullying | 35.3 | 28.3 | 10.6 | 5.8 |

| … be a cyberbullying perpetrator | 76.8 | 16.6 | 3.6 | 2.9 |

| … play video games with harmful or age-inappropriate content (e.g., trivializing violence) | 54.4 | 30.2 | 10.2 | 5.2 |

| … watch films, series or clips with harmful or age-inappropriate content | 34.3 | 39.5 | 18.4 | 7.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Werling, A.M.; Walitza, S.; Drechsler, R. Looking Back After the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Parents’ View on Screen Media Use, Psychopathology, and Psychological Burden in a Clinical Sample of Children and Adolescents. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162026

Werling AM, Walitza S, Drechsler R. Looking Back After the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Parents’ View on Screen Media Use, Psychopathology, and Psychological Burden in a Clinical Sample of Children and Adolescents. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162026

Chicago/Turabian StyleWerling, Anna Maria, Susanne Walitza, and Renate Drechsler. 2025. "Looking Back After the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Parents’ View on Screen Media Use, Psychopathology, and Psychological Burden in a Clinical Sample of Children and Adolescents" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162026

APA StyleWerling, A. M., Walitza, S., & Drechsler, R. (2025). Looking Back After the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Parents’ View on Screen Media Use, Psychopathology, and Psychological Burden in a Clinical Sample of Children and Adolescents. Healthcare, 13(16), 2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162026