Increasing Serious Illness Conversations in Patients at High Risk of One-Year Mortality Using Improvement Science: A Quality Improvement Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Participants

2.2. Study Design

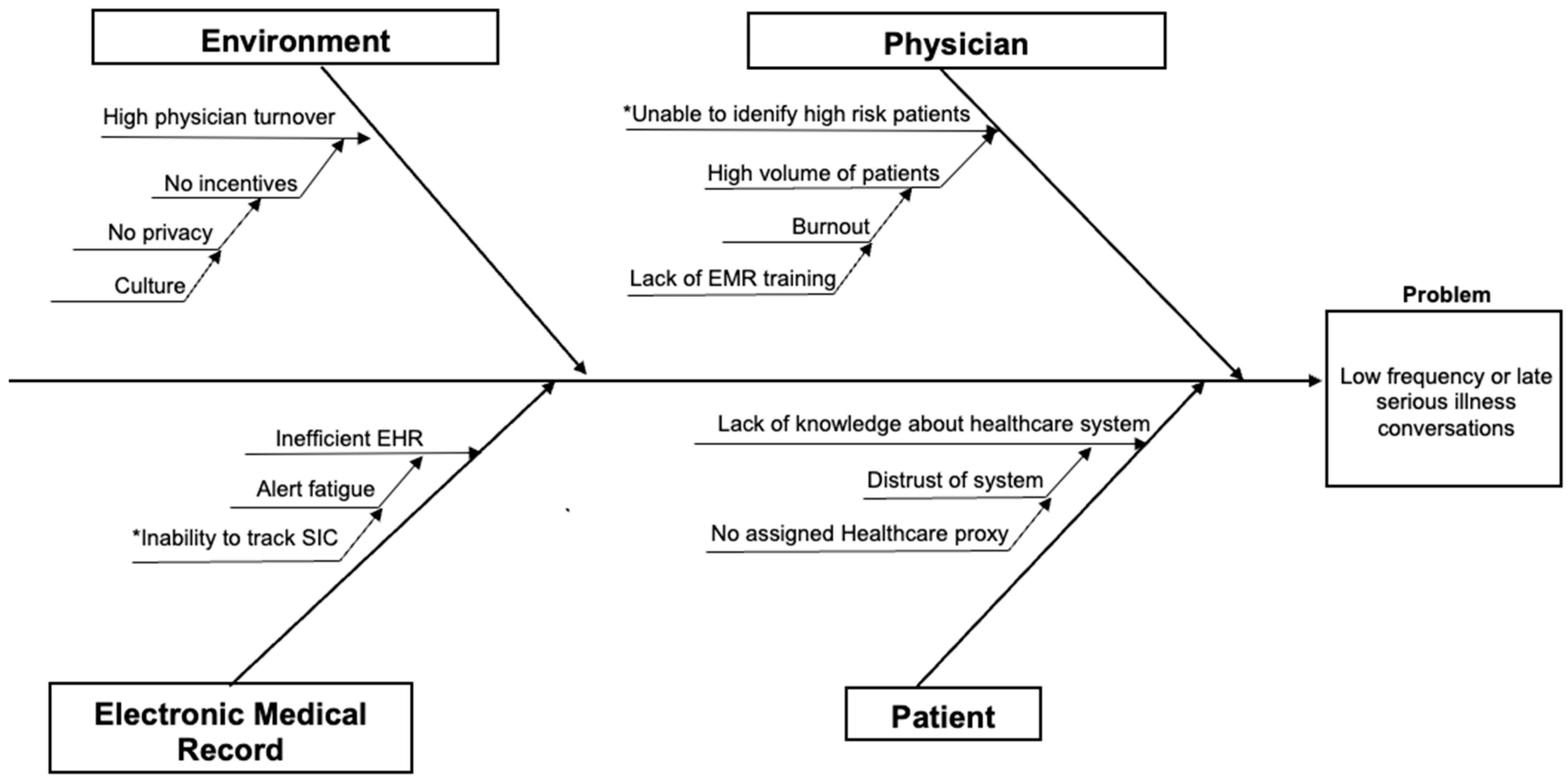

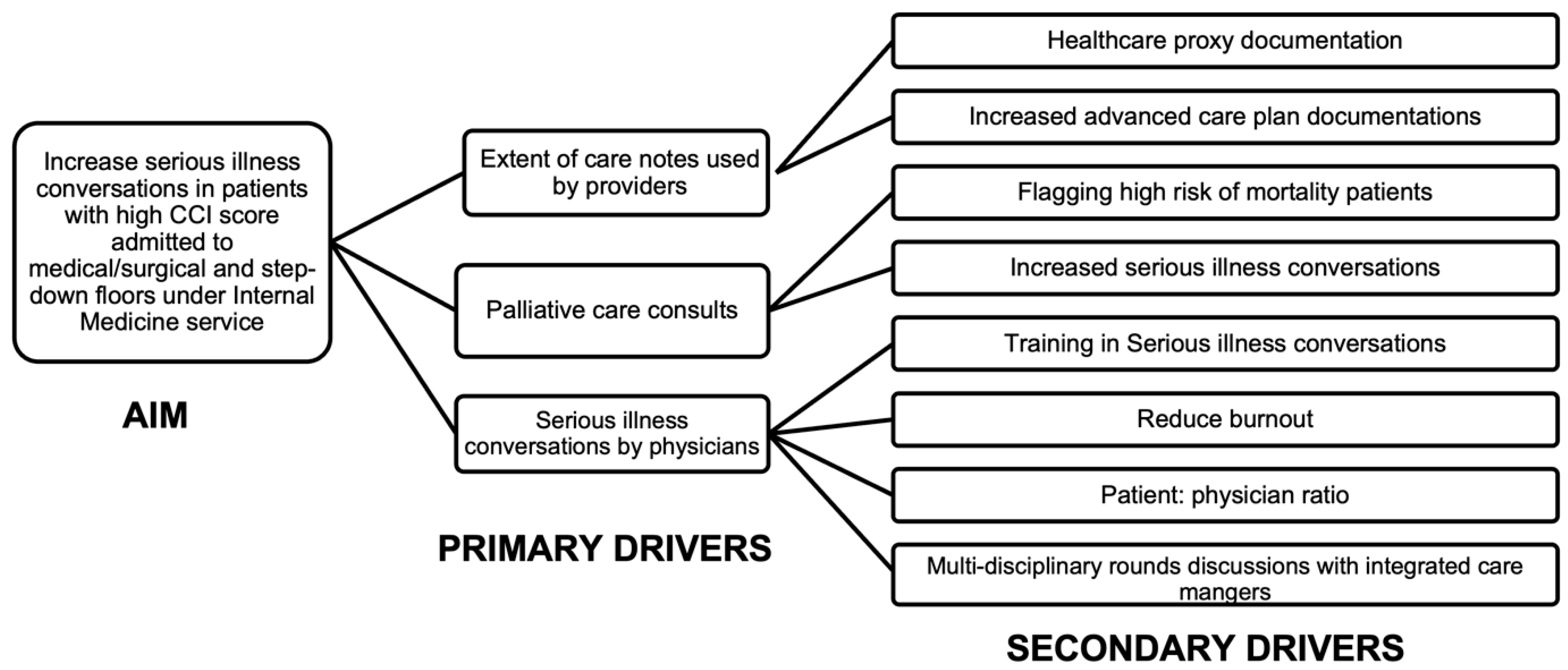

2.3. Cause-and-Effect Analysis and Driver Diagram

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.6. Data Management

2.7. Qualitative Feedback and Stakeholder Engagement

2.8. Measures

2.9. Statistical Analysis

2.10. Ethics

3. Results

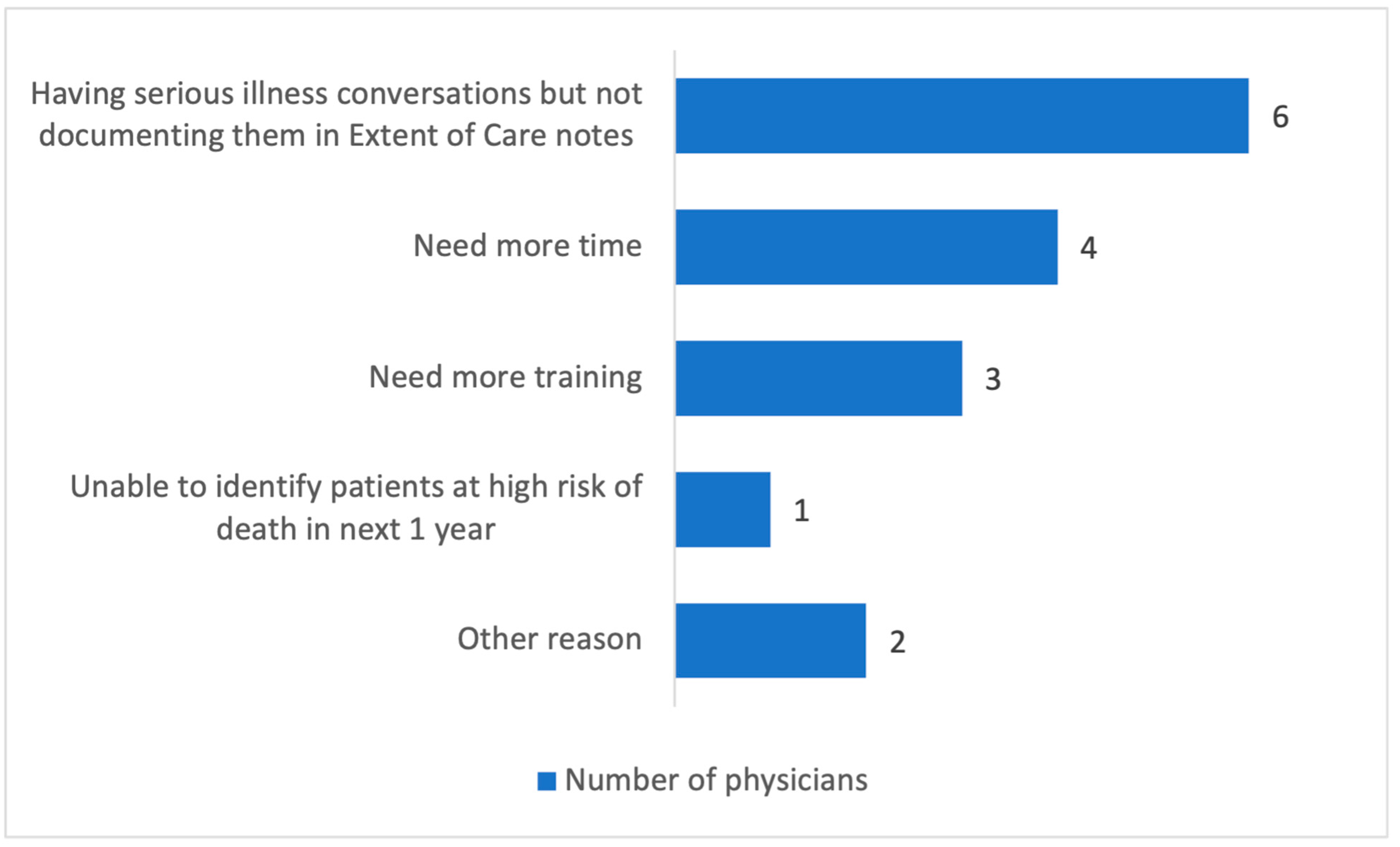

Post-Intervention Feedback Using Redcap Survey

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Direction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SIC | Serious illness conversation |

| QI | Quality improvement |

| ACP | Advance care plan |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| EOC | Extent of care |

| EHR | Electronic health record |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| PDSA | Plan–do–study–act |

| DNR | Do not resuscitate |

| DNI | Do not intubate |

References

- Shilling, D.M.; Manz, C.R.; Strand, J.J.; Patel, M.I. Let Us Have the Conversation: Serious Illness Communication in Oncology: Definitions, Barriers, and Successful Approaches. AAm. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2024, 44, e431352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Con, A.; Christie, G.; Hawley, P.H. Goals of care and end-of-life decision making for hospitalized patients at a canadian tertiary care cancer center. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2009, 38, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detering, K.M.; Hancock, A.D.; Reade, M.C.; Silvester, W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010, 340, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernacki, R.E.; Block, S.D. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 1994–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, R.; Fromme, E.K.; Sandgren, A. Patient Identification for Serious Illness Conversations: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, J.R.; Kross, E.K.; Stapleton, R.D. The Importance of Addressing Advance Care Planning and Decisions About Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders During Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA 2020, 323, 1771–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, A.M.; Arko, C.; Chen, S.C.; Gilbertson, D.T.; Moss, A.H. Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 1, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, S.N. End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, E.; Harth, T.; Hruby, G.; Finkelstein, J.; Wu, J.; Danjoux, C. How Accurate are Physicians’ Clinical Predictions of Survival and the Available Prognostic Tools in Estimating Survival Times in Terminally III Cancer Patients? A Systematic Review. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 13, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lally, K.; Fulton, A.T.; Ducharme, C.; Scott, R.; Filpo, J.A. Using Nurse Care Managers Trained in the Serious Illness Conversation Guide to Increase Goals-of-Care Conversations in an Accountable Care Organization. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, J.R.; Lee, R.Y.; Brumback, L.C.; Kross, E.K.; Downey, L.; Torrence, J.; LeDuc, N.; Andrews, K.M.; Im, J.; Heywood, J.; et al. Intervention to Promote Communication about Goals of Care for Hospitalized Patients with Serious Illness: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 329, 2028–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollak, K.I.; Gao, X.; Beliveau, J.; Griffith, B.; Kennedy, D.; Casarett, D. Pilot Study to Improve Goals of Care Conversations Among Hospitalists. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2019, 58, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, H.; Li, B.; Couris, C.M.; Fushimi, K.; Graham, P.; Hider, P.; Januel, J.-M.; Sundararajan, V. Updating and validating the charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 173, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langley, G.J. (Ed.) The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, S.; Harle, I.; O’Donnell, J.; Li, S.; Booth, C.M. Documenting Goals of Care Among Patients with Advanced Cancer: Results of a Quality Improvement Initiative. J. Oncol. Pract. 2018, 14, e557–e565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, A.H.; Lunney, J.R.; Culp, S.; Auber, M.; Kurian, S.; Rogers, J.; Dower, J.; Abraham, J. Prognostic significance of the ‘surprise’ question in cancer patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2010, 13, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, N.A.; Lamont, E.B. Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: Prospective cohort study. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2000, 320, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, J.J.; Fowler, R.A.; Heyland, D.K. Just ask: Discussing goals of care with patients in hospital with serious illness. CMAJ 2014, 186, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.M.; De Peralta, S.S. Triggering goals of care conversations in heart failure patients. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2022, 34, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haley, E.M.; Meisel, D.; Gitelman, Y.; Dingfield, L.; Casarett, D.J.; O’Connor, N.R. Electronic Goals of Care Alerts: An Innovative Strategy to Promote Primary Palliative Care. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

| Measure | Operational Definition |

|---|---|

| Patients with a high risk of one-year mortality (process measure) | Number of patients admitted under medicine service with 0% chance of survival in the next year as predicted by CCI tool. Referred to as patients having “high CCI scores”. |

| Documented EOC note (process measure) | Percentage of patients admitted under medicine service having EOC notes with documented SIC during active hospitalization (yes/no). |

| ACP document on file (outcome measure) | Percentage of patients admitted under medicine service having an ACP on file (yes/no). |

| Palliative care consult (outcome measure) | Percentage of patients admitted under medicine service having a documented palliative medicine note on file during active hospitalization (yes/no). |

| Hospice consult (outcome measure) | Percentage of patients admitted under medicine service visited by a hospice care liaison with a written note in the chart during active hospitalization (yes/no). |

| DNR code status (outcome measure) | Percentage of patients admitted under medicine service with current code status of DNR, irrespective of the timing of the change from complete code during any hospitalization (yes/no). |

| EOC Note (N = 62) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Present (N, %) | Absent (N, %) | ||

| Number of patients with | 16 (25.81) | 46 (74.19) | 0.0001 |

| ACP documentation | |||

| Yes | 10 (62.50) | 13 (28.26) | 0.01 |

| No | 6 (37.50) | 33 (71.74) | |

| DNR code status | |||

| DNR/DNI; DNR with limits | 13 (81.25) | 41 (89.13) | 0.41 |

| Full status/comfort care | 3 (18.75) | 5 (10.87) | |

| Palliative care consult | |||

| Yes | 8 (50) | 7 (15.22) | 0.005 |

| No | 8 (50) | 39 (84.78) | |

| Hospice consult | |||

| Yes | 5 (31.25) | 3 (6.52) | 0.02 |

| No | 11 (68.75) | 43 (93.48) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, K.D.; Godambe, S.A.; Chavan, P.P.; Parks-Savage, A.; Galicia-Castillo, M. Increasing Serious Illness Conversations in Patients at High Risk of One-Year Mortality Using Improvement Science: A Quality Improvement Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020199

Sharma KD, Godambe SA, Chavan PP, Parks-Savage A, Galicia-Castillo M. Increasing Serious Illness Conversations in Patients at High Risk of One-Year Mortality Using Improvement Science: A Quality Improvement Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(2):199. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020199

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Kanishk D., Sandip A. Godambe, Prachi P. Chavan, Agatha Parks-Savage, and Marissa Galicia-Castillo. 2025. "Increasing Serious Illness Conversations in Patients at High Risk of One-Year Mortality Using Improvement Science: A Quality Improvement Study" Healthcare 13, no. 2: 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020199

APA StyleSharma, K. D., Godambe, S. A., Chavan, P. P., Parks-Savage, A., & Galicia-Castillo, M. (2025). Increasing Serious Illness Conversations in Patients at High Risk of One-Year Mortality Using Improvement Science: A Quality Improvement Study. Healthcare, 13(2), 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020199