Physical Exercise Interventions Using Virtual Reality in Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

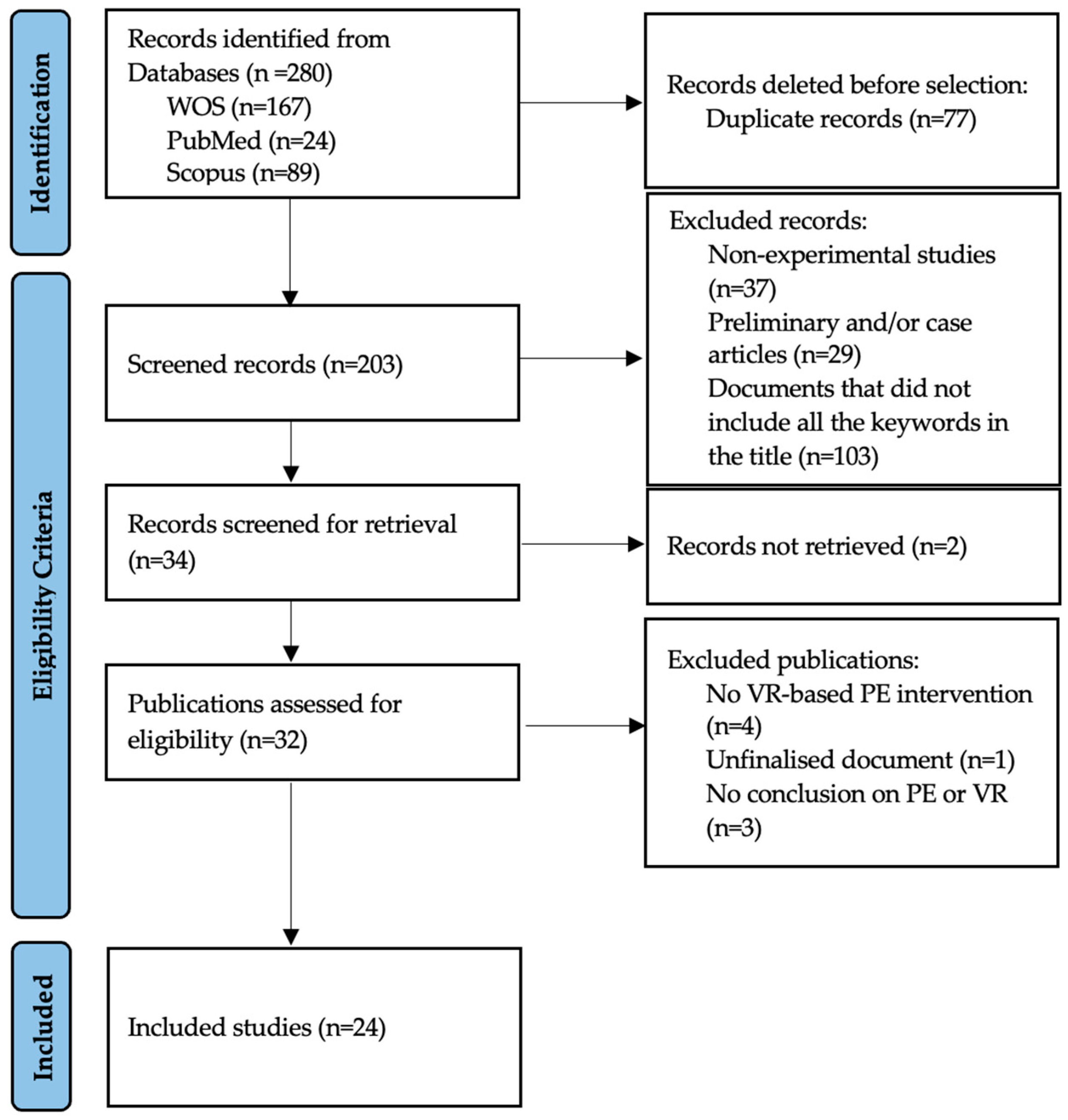

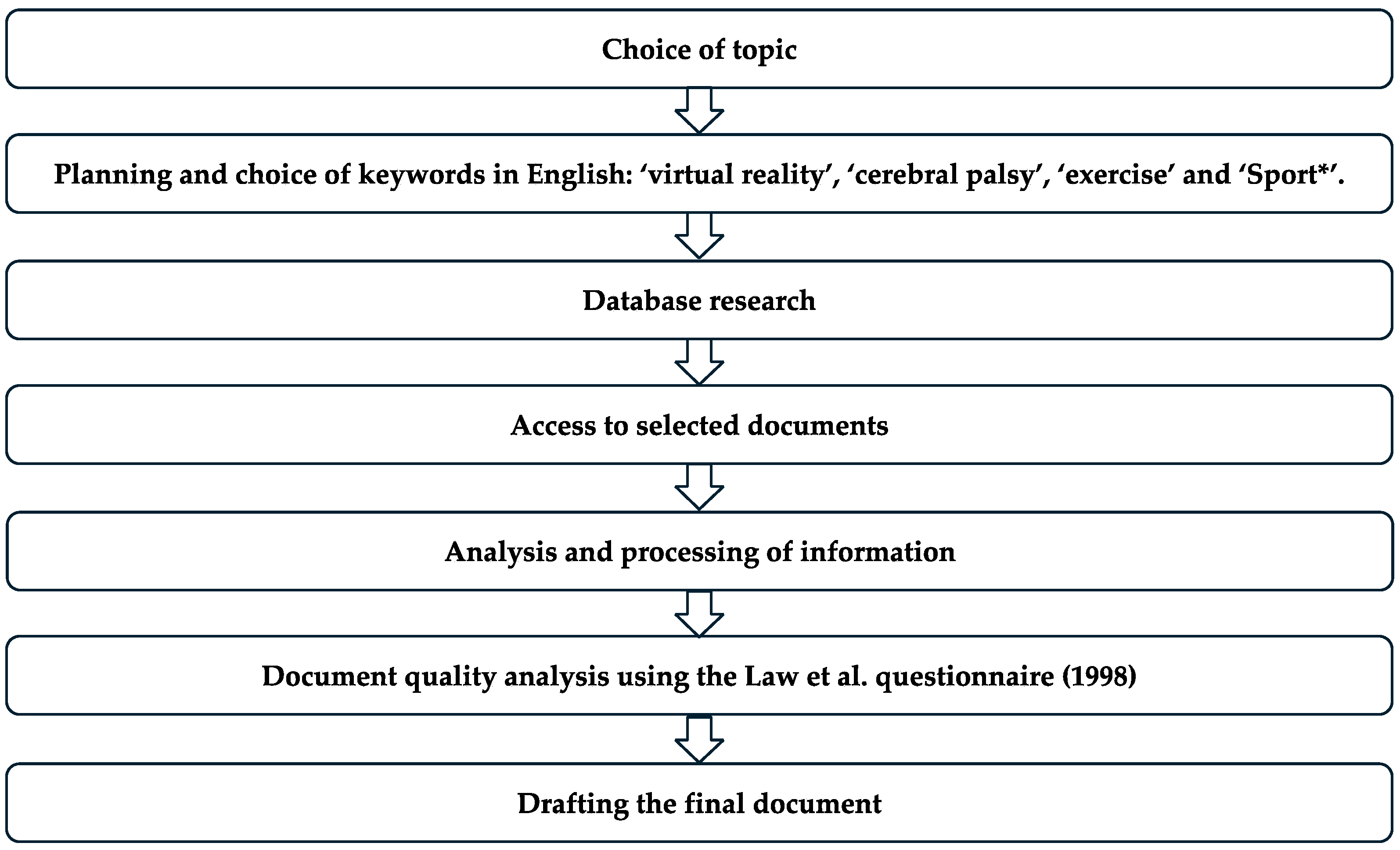

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Type and Design

2.2. PICO Strategy and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Methodological Quality Analysis

2.5. Variable Coding

2.6. Study Registration Procedure

2.7. Synthesis Methods

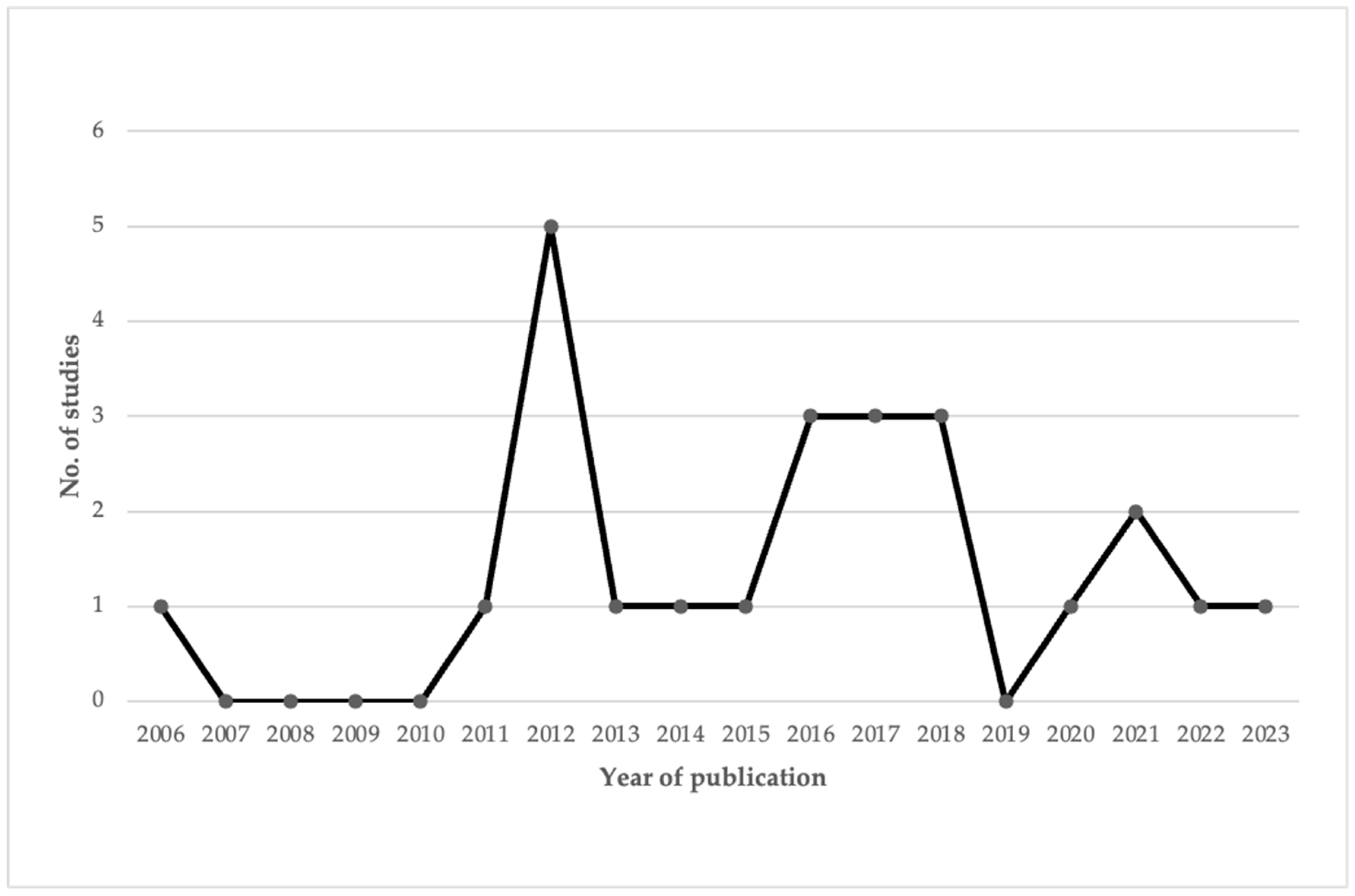

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section and Topic | Item | Checklist Item | Location Where Item Is Reported |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Page 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | Page 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | Page 2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | Page 2 |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | Page 3 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | Page 3 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | Page 3 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 3 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 3 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | Pages 4 and 5 |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | Pages 4 and 5 | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 4, page 6 and page 7 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | Page 6 to page 13 |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | Page 3 to page 5 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | Page 3 to page 5 | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | Page 3 to page 5 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | Page 3 to page 5 | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | Page 3 to page 5 | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | Page 3 to page 5 | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | Page 3 to page 5 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | Page 3 to page 5 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | Page 4 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | Page 4 | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | Page 8 to page 20 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | Page 6 and page 7 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | Page 8 to page 20 |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | Page 6 and page 7 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | No meta-analysys was done | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | Page 8 to page 20 | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | Page 8 to page 20 | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | Page 8 to page 20 |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | Page 8 to page 20 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | Page 21 and page 22 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | Page 21 and page 22 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | Page 21 and page 22 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | Page 21 and page 22 | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | Page 2 |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | Page 2 | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | Page 2 | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | Page 23 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | Page 23 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | Not applicable |

| From: Page et al., (2017) [20] | |||

References

- Cans, C. Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe. Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe: A collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe (SCPE). Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000, 42, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albesa, S.A.; Díaz, D.M.N.; Sáinz, E.A. Cerebral palsy: New challenges in the era of rare diseases. An. Sist. Sanit. Navarra. 2023, 46, e1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smithers-Sheedy, H.; Badawi, N.; Blair, E.; Cans, C.; Himmelmann, K.; Krägeloh-Mann, I.; McIntyre, S.; Slee, J.; Uldall, P.; Watson, M.; et al. What constitutes cerebral palsy in the twenty-first century? Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014, 56, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- García Ron, A.; Arriola Pereda, G.; Machado Casas, I.S.; Pascual Pascual, I.; Garriz Luis, M.; García Ribes, A.; Paredes Mercado, C.; Aguilera Albesa, S.; Peña Segura, J.L. Parálisis Cerebral. Available online: www.aeped.es/protocolos/ (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Ryan, J.M.; Cassidy, E.E.; Noorduyn, S.G.; O’Connell, N.E. Exercise interventions for cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD011660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verschuren, O.; Peterson, M.D.; Balemans, A.C.J.; Hurvitz, E.A. Exercise and physical activity recommendations for people with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2016, 58, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verschuren, O.; Wiart, L.; Hermans, D.; Ketelaar, M. Identification of facilitators and barriers to physical activity in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. J. Pediatr. 2012, 161, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagos-Manríquez, G.; Gallardo-Riquelme, R.; Campos-Campos, K.; Luarte-Rocha, C. Barreras y facilitadores para la práctica de actividad física en niños y jóvenes con parálisis cerebral: Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Cienc. Act. Fis. 2022, 23, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Cantero, A.J.; Pousada García, T.; Pacheco-da-Costa, S.; Lebrato-Vázquez, C.; Mendoza-Sagrera, A.; Meriggi, P.; Gómez-González, I.M. Physical Activity in Cerebral Palsy: A Current State Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.; McDonough, D.J.; Gao, Z. The effectiveness of virtual reality exercise on individual’s physiological, psychological and rehabilitative outcomes: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge Pereira, E.; Molina Rueda, F.; Alguacil Diego, I.M.; Cano de la Cuerda, R.; de Mauro, A.; Miangolarra Page, J.C. Empleo de sistemas de realidad virtual como método de propiocepción en parálisis cerebral: Guía de práctica clínica. Neurologia 2014, 29, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, R.; Cahalin, L.P.; Borghi-Silva, A.; Phillips, S.A. Improving functional capacity in heart failure: The need for a multifaceted approach. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2014, 29, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo-Bellot, A.; Rodríguez-Seoane, S. Effectiveness of virtual reality and video games on postural control and balance in children with cerebral palsy in Early Intervention. Fisioterapia 2022, 44, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Wu, J. The effect of virtual reality games on the gross motor skills of children with cerebral palsy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Argote, J. Use of virtual reality in rehabilitation. Interdiscip. Rehabil. 2022, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateni, H.; Carruthers, J.; Mohan, R.; Pishva, S. Use of Virtual Reality in Physical Therapy as an Intervention and Diagnostic Tool. Rehabil. Res. Pract. 2024, 2024, 1122286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ato, M.; López, J.J.; Benavente, A. Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Nelson, J.; Silverman, S. Métodos de Pesquisa em Atividade Física, 6th ed.; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo, C.P.; Soria Viteri, J. Research Question and Picot Strategy. Rev. Med. 2015, 19, 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Law, M.; Stewart, D.; Pollock, N.; Letts, L.; Bosch, J.; Westmorland, M. Guidelines for Critical Review Form—Quantitative Studies. 1998. Available online: https://canchild.ca/system/tenon/assets/attachments/000/000/366/original/quantguide.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Sarmento, H.; Clemente, F.M.; Araújo, D.; Davids, K.; McRobert, A.; Figueiredo, A. What Performance Analysts Need to Know About Research Trends in Association Football (2012–2016): A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 799–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Beltrán, V.; Espada, M.C.; Santos, F.J.; Ferreira, C.C.; Gamonales, J.M. Documents Publication Evolution (1990–2022) Related to Physical Activity and Healthy Habits, a Bibliometric Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savovic, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.j.; Cheng, H.-J.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gámez-Calvo, L.; Hernández-Beltrán, V.; Correia Campos, L.F.; Chalapud-Narvaez, L.M.; Espada, M.C.; Gamonales, J.M. Analysis of covid-19 in models of play in children. Systematic review. EA Esc. Abierta 2024, 27, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Beltrán, V.; Muñoz-Jiménez, J.; Gámez-Calvo, L.; Correia Campos, L.F.; Gamonales, J.M. Influence of injuries and functional classification on the sport performance in wheelchair basketball players. Retos 2022, 45, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamonales, J.M.; Muñoz-Jiménez, J.; León-Guzmán, K.; Ibáñez, S.J. 5-A-side football for individuals with visual impairments: A review of the literature. Eur. J. Adapt. Phys. Act. 2018, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryanton, C.; Bossé, J.; Brien, M.; Mclean, J.; Mccormick, A.; Sveistrup, H. Feasibility, Motivation, and Selective Motor Control: Virtual Reality Compared to Conventional Home Exercise in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2006, 9, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brien, M.; Sveistrup, H. An intensive virtual reality program improves functional balance and mobility of adolescents with cerebral palsy. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2011, 23, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.L.; Hong, W.H.; Cheng, H.Y.K.; Liaw, M.Y.; Chung, C.Y.; Chen, C.Y. Muscle strength enhancement following home-based virtual cycling training in ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Chen, C.Y.; Liaw, M.Y.; Chung, C.Y.; Wang, C.J.; Hong, W.H. Efficacy of home-based virtual cycling training on bone mineral density in ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelsma, J.; Pronk, M.; Ferguson, G.; Jelsma-Smit, D. The effect of the Nintendo Wii Fit on balance control and gross motor function of children with spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2013, 16, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, H.R.; Arastoo, A.A.; Nejad, S.J.; Mahany, M.K.; Malamiri, R.A.; Goharpey, S. Effects of modified constraint-induced movement therapy in virtual environment on upper-limb function in children with spastic hemiparetic cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation 2012, 31, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkels, D.G.M.; Kottink, A.I.R.; Temmink, R.A.J.; Nijlant, J.M.M.; Buurke, J.H. Wii™-habilitation of upper extremity function in children with cerebral palsy. An explorative study. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2013, 16, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosie, J.A.; Ruhen, S.; Hing, W.A.; Lewis, G.N. Virtual rehabilitation in a school setting: Is it feasible for children with cerebral palsy? Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2015, 10, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, H.C.; Ada, L.; Lee, H.M. Upper limb training using Wii Sports Resort™ for children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: A randomized, single-blind trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2014, 28, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.W.; Song, G.G.; Hwangbo, G. Effects of conventional neurological treatment and a virtual reality training program on eye-hand coordination in children with cerebral palsy. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 2151–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedair, R.; Al-Talawy, H.; Shoukry, K.; Abdul-Raouf, E. Impact of virtual reality games as an adjunct treatment tool on upper extremity function of spastic hemiplegic children. Int. J. PharmTech. Res. 2016, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, C.; Hwang, W.; Hwang, S.; Chung, Y. Treadmill training with virtual reality improves gait, balance, and muscle strength in children with cerebral palsy. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2016, 238, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarakci, D.; Ersoz Huseyinsinoglu, B.; Tarakci, E.; Razak Ozdincler, A. Effects of Nintendo Wii-Fit® video games on balance in children with mild cerebral palsy. Pediatr. Int. 2016, 58, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatica-Rojas, V.; Méndez-Rebolledo, G.; Guzman-Muñoz, E.; Soto-Poblete, A.; Cartes-Velásquez, R.; Elgueta-Cancino, E.; Cofré Lizama, E. Does Nintendo Wii Balance Board improve standing balance? A randomized controlled trial in children with cerebral palsy. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 53, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourazar, M.; Mirakhori, F.; Hemayattalab, R.; Bagherzadeh, F. Use of virtual reality intervention to improve reaction time in children with cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled trial. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2018, 21, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.W.; Lee, D.R.; Cha, Y.J.; You, S.H. Augmented effects of EMG biofeedback interfaced with virtual reality on neuromuscular control and movement coordination during reaching in children with cerebral palsy. NeuroRehabilitation 2017, 40, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, H.C.; Ada, L.; Lee, S.D. Balance and mobility training at home using Wii Fit in children with cerebral palsy: A feasibility study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Shamy, S.M.; El-Banna, M.F. Effect of Wii training on hand function in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2020, 36, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.; Levac, D.; Sveistrup, H. The effects of a 5-day virtual-reality-based exercise program on kinematics and postural muscle activity in youth with cerebral palsy. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2019, 39, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, H.; Shierk, A.; Clegg, N.J.; Baldwin, D.; Smith, L.; Yeatts, P.; Delgado, M.R. Constraint induced movement therapy camp for children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy augmented by use of an exoskeleton to play games in virtual reality. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2020, 41, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gercek, N.; Tatar, Y.; Uzun, S. Alternative exercise methods for children with cerebral palsy: Effects of virtual vs. traditional golf training. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 68, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, K.K.; Karunanithi, G.B.; Sahana, A.; Karthikbabu, S. Randomised trial of virtual reality gaming and physiotherapy on balance, gross motor performance and daily functions among children with bilateral spastic cerebral palsy. Somatosens. Mot. Res. 2021, 38, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, S.A.; Waked, N.M.; Helmy, A.M. Effect of virtual reality games on motor performance level in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Physiother. Quart. 2022, 30, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saussez, G.; Bailly, R.; Araneda, R.; Paradis, J.; Ebner-Karestinos, D.; Klöcker, A.; Sogbossi, E.S.; Riquelme, I.; Brochard, S.; Bleyenheuft, Y. Efficacy of integrating a semi-immersive virtual device in the HABIT-ILE intervention for children with unilateral cerebral palsy: A non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Cerebral Palsy: Hope Through Research. Available online: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Hope-Through-Research/Cerebral-Palsy-Hope-Through-Research (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Confederación ASPACE. Tipos de Parálisis Cerebral. Available online: https://aspace.org/tipos-de-paralisis-cerebral (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Verschuren, O.; Darrah, J.; Novak, I.; Ketelaar, M.; Wiart, L. Health-enhancing physical activity in children with cerebral palsy: More of the same is not enough. Phys. Ther. J. 2014, 94, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (accessed on 9 November 2024).

| Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| People with CP aged 5 to 18 years | PE program using VR as the main tool | Traditional intervention methods or no therapy | Provides results related to quality of life and willing to engage in PE |

| Selection Criteria | Inclusion |

|---|---|

| Document Type | Scientific article. |

| Study Type | Documents with experimental design. |

| Study Subjects | Sample of subjects aged 5 to 18 years with CP. |

| Methodology | Intervention focused on a PE program using VR. |

| Exclusion | |

| Study Type | Documents with non-experimental methodologies, case studies, or preliminary studies. |

| Medical Conditions | Studies include participants with additional medical conditions that may affect intervention participation. |

| Conclusion | Conclusions that focus on aspects other than PE and VR or do not report intervention outcomes. |

| General Variables | |

| Author/s | Original author/s of the publication. |

| Year | Year of publication. |

| Sample | Number of participants, age, gender, and type of CP. |

| Objective | Main objectives of each study. |

| Conclusions | Key conclusions of the study. |

| Specific Variables | |

| Study variables and their evaluation tools | Variables measured in each study and the various tools used. |

| Material and type of VR | Materials and used VR tools. |

| Type and duration of exposure and measurements | Specifies the type and duration of the intervention performed and the measurements taken. |

| Main results | Results from the measurements obtained from the study variables. |

| Methodological Quality | |

| Methodological quality | The Law et al. [23] questionnaire was applied to the studies, with the rating proposed by Sarmento et al. [24]. |

| Study and Publication Year | Selection Bias | Performance Bias | Detection Bias | Attrition Bias | Reporting Bias | Other Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bryanton et al., 2006 [30] | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Brien and Sveistrup, 2011 [31] | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Chen et al., 2012a [32] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Chen et al., 2012b [33] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Jelsma et al., 2012 [34] | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Rostami et al., 2012 [35] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Winkels et al., 2013 [36] | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Rosie et al., 2013 [37] | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Chiu et al., 2014 [38] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Shin et al., 2015 [39] | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Bedair et al., 2016 [40] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Cho et al., 2016 [41] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Tarakci et al., 2016 [42] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Gatica-Rojas et al., 2017 [43] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Pourazar et al., 2017 [44] | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Yoo et al., 2017 [45] | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Chiu et al., 2018 [46] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| El-Shamy et al., 2018 [47] | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Mills et al., 2018 [48] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Roberts et al., 2020 [49] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Gercek et al., 2021 [50] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Jha et al., 2021 [51] | Low | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Hamed et al., 2022 [52] | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Saussez et al. 2023 [53] | Unclear | High | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| ID | Citation and Publication Year | Sample | Objectives | Conclusions | Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bryanton et al., 2006 [30] | 16 children aged 7 to 17 years, 10 with CP level I-II of GMFCS (4 boys and 6 girls), and 6 without CP (2 boys and 4 girls). Subjects with CP had a GMFCS level I-II. | Compare the effectiveness of motor control exercises in children with CP using VR or conventional methods, assessing children’s motivation and compliance and whether improvements in ROM and hold time transfer to daily activities. | VR exercises for children with CP resulted in greater ankle ROM, better movement control, and increased interest compared to conventional exercises. | B |

| 2 | Brien & Sveistrup, 2011 [31] | 4 adolescent boys aged 14 to 18 years, with CP, level I of GMFCS, and the ability to follow standardized test instructions. | Conduct a short-term intensive VR program aimed at improving balance and mobility in adolescents with CP. | High-level balance skills and functional mobility are modifiable in this population. | A |

| 3 | Chen et al., 2012a [32] | 27 children, aged 6 to 12 years, both genders, with spastic CP levels I-II of GMFCS. | Analyze an HVCT program and its impact on ABMD in ambulatory children with CP. | The muscle-strengthening program is more specific for improving bone density in children with CP than general physical activity. The proposed protocol is an effective and efficient strategy to improve ABMD in the lower limbs. | A |

| 4 | Chen et al., 2012b [33] | 28 children, aged 6 to 12 years, both genders, spastic CP levels I-II of GMFCS. | Evaluate the effect of an HVCT program to improve muscle strength in ambulatory children with spastic CP. | The HVCT program did not improve gross motor function but significantly increased knee muscle strength in children with spastic CP. The greatest benefits were seen in knee flexor muscles. | A |

| 5 | Jelsma et al., 2012 [34] | 14 children, aged between 7 and 14 years, 8 boys and 6 girls, with spastic hemiplegic CP and GMFCS levels I-II. | The aim was to evaluate the impact of training with Nintendo Wii Fit on balance and gross motor function in children with spastic hemiplegic CP and compare it to conventional physiotherapy. | Training with Nintendo Wii Fit improved balance in children with spastic hemiplegic CP, and there was a preference for VR training over conventional physiotherapy. However, there were no significant improvements in agility or the ability to go up and down stairs. It was recommended as a useful complement to conventional physiotherapy but not as a replacement. | A |

| 6 | Rostami et al., 2012 [35] | 32 participants, aged 6 to 11 years, 18 girls and 14 boys, with spastic hemiparetic CP with a MAS score below 3. | Determine the effects of a modified constraint-induced movement therapy practice period in a virtual environment on upper limb function in children with spastic hemiparetic CP. | Modified constraint-induced movement therapy in a virtual environment could be a promising rehabilitation procedure to enhance the benefits of both VR and this type of therapy. | A |

| 7 | Winkels et al., 2013 [36] | 15 children, aged between 6 and 15 years, 12 boys and 3 girls, with CP (8 with bilateral spastic CP, 6 with unilateral spastic CP, and 1 with ataxic CP) and the ability to hold the Wii controller, with a minimum score of 11% on the MUUL. | To explore the effects of Nintendo Wii training on the upper limbs in children with CP, as well as to evaluate user satisfaction and usability for both participants and professionals and to assess if the intervention was enjoyable. | The use of VR and games can be very interesting as a tool, and it can be motivating and help improve functional arm performance in children with CP. However, not all games may serve this purpose, so specially developed or adapted games would be a better option. | A |

| 8 | Rosie et al., 2013 [37] | 5 children, aged 7 to 13 years, 3 girls and 2 boys, with CP, level I-II in GMFCS. | Evaluate the feasibility of a school-based virtual rehabilitation program for children with CP and whether it is feasible to implement the IREX system supervised by teachers in isolated areas without regular access to therapy. | The IREX system is feasible to implement in a school environment supervised by teachers. It is an option to provide physical therapy to children in isolated areas who do not receive continuous therapy. | B |

| 9 | Chiu et al., 2014 [38] | 62 participants, aged between 6 and 13 years, 28 boys and 34 girls, with spastic hemiplegic CP and sufficient manual function to hold the Wii remote control. | To evaluate the effectiveness of Wii Sports Resort training in improving hand coordination, strength, and function in children with hemiplegic CP to see if improvements are sustained up to 6 weeks post-intervention and to assess the feasibility of home-based training. | There were no significant improvements between the two groups, but caregivers reported increased hand use after Wii Sports Resort training. Commercial video games could be a motivating form of home exercise for children with CP. | A |

| 10 | Shin et al., 2015 [39] | 16 children, aged 4 to 8 years, 9 boys and 7 girls with spastic diplegic CP, with motor function level I, II, or III on the GMFCS scale. | Evaluate the effects of conventional neurological treatment and a virtual reality training program on hand-eye coordination in children with CP. | A well-designed VR training program can improve hand-eye coordination in children with CP. | A |

| 11 | Bedair et al., 2016 [40] | 40 children, aged 5 to 10 years, 23 boys and 17 girls, with spastic hemiplegic CP and a grade 1+ or 2 on the MAS. | To assess the effects of VR games as a complementary tool for upper limb treatment in children with spastic hemiplegia. | VR games significantly improved motor and visual skills in children with spastic hemiplegia. It is believed that the children’s active participation and motivation in a simulated environment contributed to these improvements, facilitating cortical reorganization and the development of new motor pathways. | A |

| 12 | Cho et al., 2016 [41] | 18 children, aged 4 to 16 years with spastic CP, level I-III on GMFCS, and a score of less than 2 on MAS. | Investigate the effects of VR treadmill training [VRTT) in children with CP, comparing it to traditional treadmill training, focusing on improving gait, balance, muscle strength, and gross motor function. | VRTT is effective in improving gait, balance, muscle strength, and gross motor function in children with CP, although future studies are suggested to confirm long-term efficacy. | A |

| 13 | Tarakci et al., 2016 [42] | 30 children, aged 5 to 18 years, 19 boys and 11 girls, 12 with diparetic CP, 14 with hemiparetic CP, and 4 with dyskinetic CP, with levels I-III on the GMFCS. | To determine if Wii Fit video games improve static and dynamic balance and independence in daily activities compared to conventional balance training in children with mild CP. | Nintendo Wii Fit training combined with NDT significantly improved static and dynamic balance in children with mild CP. It also resulted in greater independence in daily activities, and increased motivation and satisfaction among both children and their families, making the treatment more appealing. | A |

| 14 | Gatica-Rojas et al., 2017 [43] | 32 children, aged 7 to 14 years, gender not specified, with spastic hemiplegic and diplegic CP, with levels I-II on the GMFCS. | To compare the post-treatment effects and effectiveness of Nintendo Wii Balance Board therapy versus standard physiotherapy on standing balance in children and adolescents with CP. | Nintendo Wii Balance Board therapy improved balance in CP patients more than standard physiotherapy, especially in those with spastic hemiplegia. However, the positive effects diminished by the 2nd and 4th week after the intervention. Wii therapy is easy to implement in rehabilitation centers and can be a useful tool to improve balance in CP patients. | A |

| 15 | Pourazar et al., 2017 [44] | 30 boys, aged 7 to 12 years, all with spastic hemiplegic CP, level I-III on GMFCS, and level I-II on MACS. | Investigate the effects of VR intervention program training on reaction time in children with CP. | This study suggests VR as a promising tool in the rehabilitation process to improve reaction time in children with CP. | A |

| 16 | Yoo et al., 2017 [45] | 18 children (2 girls and 10 boys with spastic CP and 3 girls and 5 boys without CP), aged 9.5 ± 1.96 years for CP children, and 9.75 ± 2.55-year-old children with CP had a level I-III on the MACS and a grade 1 on the MAS. | Compare the therapeutic effects of VR-augmented EMG biofeedback and EMG biofeedback alone on the imbalance of tricep and bicep muscle activity and coordination of elbow joint movement during a reaching motor task. | VR-augmented EMG feedback produced better neuromuscular control of the elbow joint than EMG feedback alone. | A |

| 17 | Chiu et al., 2018 [46] | 20 children, aged 6 to 12 years, 11 boys and 9 girls, with CP (10 with diplegia, 8 with hemiplegia, and 2 with tetraplegia), and with levels I-III on the GMFCS. | To assess whether Wii Fit training is feasible and can improve strength, balance, mobility, and participation in children with CP. | Home-based Wii Fit training is feasible and safe for children with CP and appears to have clinical benefits for strength and mobility in this population. A randomized controlled trial is suggested to investigate further. | A |

| 18 | El-Shamy et al., 2018 [47] | 40 children, aged 8 to 12 years, 26 boys and 14 girls, with spastic hemiplegic CP, capable of following simple instructions, with no prior Wii experience, and able to use the Wii safely, with levels I-III on the MACS. | To investigate the effect of Nintendo Wii training on the function of the affected hand in children with hemiplegic CP. | Wii training, combined with standard therapy, can reduce spasticity, increase grip strength, and improve manual function in children with spastic hemiplegic CP. The intervention had a high adherence rate, suggesting that Wii games can be a motivating and effective tool in rehabilitation. | A |

| 19 | Mills et al., 2018 [48] | 11 children, aged 7 to 17 years, 6 boys and 5 girls, all with CP and a level I-II of GMFCS. | Evaluate the effects of a 5-day VR-based exercise program on anticipatory and reactive postural control mechanisms in children and youth with CP. | No effect was observed from the 5-day VR-based intervention on postural control mechanisms used in response to platform perturbations. | B |

| 20 | Roberts et al., 2020 [49] | 31 children (16 boys and 15 girls) with hemiplegic CP, aged 5 to 15 years, with a classification of I-III on the MACS. | Determine the acceptability and effects of a P-CIMT camp for children with hemiplegic CP augmented by using an exoskeleton for playing in VR. | A P-CIMT camp augmented by the Hocoma Armeo Spring Pediatric was feasible and accepted by participants. Bimanual hand function and occupational performance improved immediately after the intervention, and treatment effects persisted for at least 6 months. | A |

| 21 | Gercek et al., 2021 [50] | 19 children, aged 6 to 12 years, 14 boys and 5 girls, with hemiplegic CP, and level I and II on GMFCS. | Investigate how virtual and traditional golf affects balance, muscle strength, lower limb flexibility, and aerobic endurance in children with CP. | Both virtual and traditional golf training can be effective complementary applications for improving lower limb functions and physical performance in children with CP. | A |

| 22 | Jha et al., 2021 [51] | 38 children, aged 6 to 12 years, all with bilateral spastic CP with a GMFCS level of II-III and I-III on the MACS. | Examine the effects of VR games and physiotherapy on balance, gross motor performance, and daily functioning in children with bilateral spastic CP. | The combination of VR games and physiotherapy is not superior to physiotherapy alone in improving gross motor performance and daily functioning but is better for balance in children with bilateral spastic CP. | A |

| 23 | Hamed et al., 2022 [52] | 30 children (boys and girls) aged 7 to 10 years with spastic diplegic CP with a score of 2 or less on MAS. | Examine the effects of VR games on motor performance levels in children with spastic CP. | The use of a VR-based video game system in the rehabilitation program for patients with CP could be considered an effective intervention method and could be added to treatment programs, as it resulted in a significant improvement in motor performance levels. | A |

| 24 | Saussez et al. 2023 [53] | 40 children, aged between 5 and 18 years old, 20 boys and 20 girls, all with hemiplegic CP with levels I-II on the GMFCS and I-III on the MACS. | To compare whether the integration of REAtouch® in the HABIT-ILE intervention is at least as effective as the conventional HABIT-ILE intervention for children with hemiplegic CP. | The use of the virtual REAtouch® device is not inferior in efficacy compared to conventional HABIT-ILE intervention in children with CP. This demonstrates the feasibility of using this device and establishes the possibility of applying therapeutic principles of motor skills learning in sessions based on virtual environments. | A |

| ID | Variables and Assessment Tools | Material and Type of VR | Type and Duration of Exposure and Measurement Moments of Variables | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Selective motor control and exercise compliance were both variables measured using an electrogoniometer that recorded ankle ROM. | IREX VR system, including a large TV monitor, a camera, and a computer. Two VR applications, Coconut Shooters and Ninja Flip, were created to introduce ankle movements into the virtual environment. | A single 90 min exercise session, alternating 10 min blocks between conventional and VR exercises. Exercises were performed seated on the floor and in a chair, aiming to dorsiflex the ankle to the maximum range, hold for 3 s, relax, and repeat. The measurements were taken during the training. | Children showed more interest and fun with VR games. Conventional exercises completed more repetitions at the same time, but VR exercises achieved greater ROM and retention time in the extended position. |

| 2 | Balance and Community Mobility Scale (CB and M), 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT), Timed Up and Down Stairs (TUDS), and Gross Motor Function Measure Dimension E (GMFM-E). | Commercial VR system with a 32-inch screen, a video camera, and a high-performance computer. The IREX software version 1.4 was used to create a balance training program with applications like Soccer, Zebra Crossing, Snowboard, and Gravball. | 90 min of VR-based balance training for 5 consecutive days, divided into two 45 min sessions with a 30 min break in between. Measurements were taken between 3 and 6 evaluations during the week prior to the intervention, before the training sessions on days 2 to 5, and 3 times the week after, as well as 1 month after the intervention. | Statistically significant improvements were observed in all tests (CB and M, 6MWT, TUDS, and GMFM-Dimension E). Improvements persisted for at least 1-month post-intervention. |

| 3 | Muscle strength (curl-up scores and isokinetic torques of knee extensors and flexors measured with an isokinetic dynamometer), lumbar spine and distal femur ABMD (DXA), and motor function (GMFM-66). | Eloton SimCycle Virtual Cycling System connected to a personal computer using Eloton Theater CD-ROMs, which allowed access to interactive virtual worlds. The cycling resistance was adjusted using a nylon tension strap. | 12-week intervention with 3 sessions of 40 min per week. The control group (14 children) completed general physical activities at home, and the experimental group (13 children) performed HVCT. Measurements were taken between 3 and 6 evaluations during the week prior to the intervention, before the training sessions on days 2 to 5, and 3 times the week after, as well as 1 month after the intervention. | The HVCT group showed significant improvement in distal femur ABMD, and knee extensor and flexor strength compared to the control group. No significant differences were found in lumbar spine ABMD between groups, and no significant differences were observed in GMFM-66. |

| 4 | Isokinetic knee extensor and flexor torque (isokinetic dynamometer), gross motor function (BOTMP and GMFM-66), and strength change index. | Eloton SimCycle Virtual Cycling System and VR environment connected to a computer and CD-ROMs guiding users through virtual exercises. | RCT with two random groups: an experimental group and a control group. The intervention lasted 12 weeks, with the experimental group performing HVCT 3 times a week for 40 min, including warm-up, cycling, and cool-down. Measurements were taken before and after the 12 weeks of intervention. | HVCT significantly improved muscle strength without affecting gross motor function. Flexor muscles of the knee showed greater strength increases than extensors. |

| 5 | Balance and RSA (BOTMP-2) were measured, as well as functional mobility (TUDS). | The Nintendo Wii Fit was used, which included a balance board that measured the user’s weight distribution and center of pressure. The Wii Fit games played were snowboarding, skiing, and hula hoop. | Participants were randomly assigned to two groups; one group started in week 3 and the other in week 5. The intervention consisted of 25 min sessions with the Nintendo Wii Fit four times a week for three weeks. The measurements of the variables were taken before, during, and weekly up to 9 weeks after the intervention. | There was a significant improvement in balance, but no improvements were observed in agility, speed, or the ability to ascend and descend stairs. Of the 14 children, 10 preferred the intervention with the Wii, but the improvement did not transfer to overall function. |

| 6 | Variables such as the use of the affected limb and quality of movement (QOM) were measured using the PMAL, while voluntary displacement (SD) was assessed using the BOTMP. | A Human–Machine interface was employed with the E-Link Upper Limb Exerciser (E 3000), and the E-Link Evaluation and Exercise System was used as a VR tool. Various virtual games in this system were used to be engaging and motivating from the participants’ perspective. | The group was divided into four subgroups: one completed only CIMT, another only VR, one combined both, and a control group. Over four weeks, each group completed 3 sessions per week, 90 min each, with measurements taken before, after, and three months post-treatment. | The group combining modified CIMT and VR showed significant improvements in limb use, MC, and VD, which were maintained during the 3-month follow-up. The VR and modified CIMT groups also improved but not as much as the combined group, and the control group showed no significant improvements. |

| 7 | The quality of upper limb movements was assessed (MAUULF), along with the ease with which participants performed daily activities (ABILHAND-Kids scale), and questionnaires on user satisfaction and usability for healthcare professionals were administered. | The Nintendo Wii video game console was used as a form of virtual reality, employing sports games like boxing and tennis. | A 6-week intervention was conducted, with training sessions on the Nintendo Wii twice a week for 30 min, during which boxing, and tennis were played using the more affected arm. Measurements were taken before and after the intervention. | There were no significant changes in the quality of upper limb movements; however, a significant improvement in the ease of performing daily activities was observed, along with satisfaction from both children and healthcare professionals, and enjoyment from the children. |

| 8 | Children’s motivation to participate in the IREX, their perception of the games (both measured through a structured questionnaire), and the feasibility of implementing IREX in a school setting supervised by teachers (measured through a qualitative interview) were evaluated. | The VR material used was IREX, developed by Gesture Tek, USA. This system provided a virtual sports or gaming environment that promoted motivation despite the repetitive nature of therapy, tailored to everyone. | Each participant received an individualized IREX program, which they followed for 8 weeks, 3 times a week for 30 min. The IREX was placed in the child’s school during the intervention and was supervised by a teaching assistant. The measurements were taken before and after the intervention. | The children found IREX fun and easy to use, improvements in arm movement were reported, and there was a desire to continue using IREX. The supervisor played a crucial role in the success of the intervention, and it was feasible and well-received by the teaching assistants. |

| 9 | The measurements included coordination (tracking task on a screen), strength (Power Track II dynamometer), hand function (NPT and JTTHF), and caregivers’ perceptions of hand function (Functional Use Survey). | The Wii Sports Resort game was used as a virtual reality tool, and the games selected were Bowling, Air Sports, Frisbee, and Basketball, chosen for their ability to work on upper extremities and provide immediate feedback. | Participants were divided into an experimental group (32 children) who underwent 6 weeks of training with Wii Sports Resort alongside their usual therapy and a control group (30 children) that received only the usual therapy. Measurements were taken before, immediately after, and 6 weeks after the intervention by a blinded evaluator. | There were no significant differences in coordination and hand function between the two groups. Regarding grip strength, there was a trend toward improvement in the experimental group, although it was not statistically significant. Caregivers reported a greater use of the hand in the experimental group after 6 weeks post-intervention. |

| 10 | Eye–hand coordination (EHC) and visual–motor speed (VMS) were measured. | A series of conventional therapeutic exercises were performed, and the VR group used a program with the Nintendo Wii as a tool to foster interest and participation in children. | The study lasted 8 weeks, with the control group doing 45 min of therapeutic exercise twice a week, while the VR group conducted 30 min of therapeutic exercise and 15 min of VR training twice a week. The measurements were taken before and after the intervention. | Both groups showed significant improvements in EHC and VMS, but there were no significant differences between the groups. |

| 11 | Object manipulation and visual-motor skills (PDMS-2) and manual function (ABILHAND-Kids) were measured. | The Xbox Kinect was used, and games played included tennis, bowling, golf, space pop, bubbles, and boat driving. | The group was divided into two groups of 20 participants each. The study group used the Kinect for 30 min three times a week, in addition to 60 min of physical therapy, while the control group only underwent 60 min of therapy. This intervention lasted for four months, with measurements taken before, midway through, and at the end of the intervention. | Both groups showed significant improvements in all study variables, but the control group demonstrated significantly greater improvements. |

| 12 | Muscle strength (measured with a digital manual muscle tester), gross motor function (GMFM), balance (PBS), walking speed (10MWT), and walking endurance (2MWT) were assessed. | The Nintendo Wii Fit Plus program was used for the VRTT, with participants walking with a Nintendo Wii remote at their waist, which recorded body movement acceleration using a 3D accelerometer and transmitted the information to a 42-inch television. | Participants were divided into two groups of 9, one performing VRTT and the other traditional treadmill training exercises. Both groups performed 30 min of exercise, 3 days a week for 8 weeks, along with general physical therapy for 30 min, 3 times a week for 8 weeks. Measurements were taken before and after the intervention. | Participants in the VRTT group showed significant improvements in all areas compared to the traditional exercise group. |

| 13 | Measurements included: balance (FFRT, FSRT, Nintendo Wii Fit balance, and game scores), agility (STST and TGGT), walking speed (10MWT), stair climbing (10ST), and functional independence (WeeFIM). | The Nintendo Wii console and balance board were used, along with Wii Fit games, which included ski slalom, tightrope walking, and heading a ball. All activities were projected onto a screen in a dark room for the best immersive experience. | Participants were randomly assigned to either the control group, which received NDT and conventional balance training, or the experimental group, which received NDT and played balance video games on the Wii Fit console. A total of 24 interventions were conducted over 12 weeks, with measurements taken before and after the intervention. | Both groups showed significant improvements across all variables, and the experimental group demonstrated significant improvements in balance, agility, and functional independence compared to the control group. |

| 14 | The area of sway of the center of pressure was evaluated using the AMTI OR6-7 force platform, along with standard deviation in the medial–lateral and anteroposterior directions, and the velocity of the center of pressure in these same directions (AMTI NetForce software was used for data collection, and MATLAB R2012 software was utilized for processing and calculating variables). | The Nintendo Wii Balance Board was used as virtual reality material, and a systematic exercise program called Wii therapy was employed, with games including Snowboard, Penguin Slide, Super Hula Hoop, Run Plus, and Heading Football. | Participants were divided into two groups: the experimental group, which received therapy with the Nintendo Wii balance board, and the control group, which received standard physiotherapy, with both groups consisting of 16 participants. Both groups underwent 6 weeks of intervention with 3 therapy sessions per week. Measurements were taken before the intervention and every two weeks from the start of the study until week 10 (4 weeks after the completion of the intervention). | Compared to standard physiotherapy, the experimental group significantly reduced the sway area and anteroposterior deviation in the eyes-open condition. The positive effects associated with Wii therapy diminished between weeks 8 and 10, with only children with spastic hemiplegia showing significant improvements with Wii therapy, and all participants completed the therapies without adverse effects. |

| 15 | Reaction time (SRT and DRT, both measured by the RT-888 device) and general health (GHQ) were measured. | The RV intervention device used was the Xbox 360 Kinect, and bowling (Brunswick Pro-Bowling) and golf (The Golf Club) games were utilized. | Participants were randomly divided into an experimental and control group. The experimental group participated in a 12-session RV intervention program over 4 weeks to improve motor skills and reaction time. Measurements were taken before and one day after the intervention. | After the 4-week RV intervention program, the experimental group showed a significant improvement in reaction time compared to the control group. |

| 16 | Muscle activity (EMG), movement coordination during a reaching task (3-axis accelerometer), elbow extension range of motion (ROM), bicep muscle strength (strength tests), and manual dexterity (BBT) were measured. | An EMG-VR hybrid system (QEMG-4XL) was used. | The intervention consisted of 20 sessions of biofeedback-boosted VR EMG, repeated twice a week (duration not specified). The methodology was based on VR games with functional strengthening exercises for reaching movements. The measurements were made before any intervention and again after each intervention. | Users with biofeedback-boosted VR showed significant improvements in elbow extension ROM, bicep strength, BBT, and maximum triceps muscle activity. However, it did not significantly improve coordination in three-dimensional movement acceleration. |

| 17 | The following variables were evaluated: isometric maximum strength of knee extensors, dorsiflexors, and plantarflexors of the ankle (PowerTrack II), balance (One-Leg Balance Test), walking speed (6MWT and 10MWT), and participation (Participation Assistance Scale). | The Wii Fit was used as a virtual reality system, and activities requiring weight shifting and movements, such as marching in place, squatting, and getting on and off the balance board, were selected for training. These activities were divided into two packs of four games (Balance Bubble, Table Tilt, Perfect 10, Super Hula Hoop, Ultimate Obstacle Course, Ski Jump, and Basic Step). | Participants underwent the intervention for 8 weeks, three times a week for 20 min, in addition to their usual therapy. The training consisted of playing 4 out of the 8 selected games, with each game played 12 times throughout the 24 sessions. Measurements were taken before the intervention and 8 weeks post-intervention. | 99% of the sessions were completed, and improvements in muscle strength and walking speed were observed. Parents and children found the training understandable and not interfering with daily life, and there were no significant adverse events or severe falls. |

| 18 | Spasticity (MAS), grip strength (hydraulic dynamometer), pinch strength (pinch meter), and hand function (PDMS-2) were measured. | The Nintendo Wii was used as virtual reality material, and the following games were played for training: tennis, boxing, bowling, and basketball. | Participants were randomly divided into an experimental group (which received Wii training along with usual therapy) and a control group (which only received usual therapy). The experimental group underwent Wii training for 40 min, 3 times a week for 12 weeks. Measurements were taken at the beginning of the study and after the intervention. | The experimental group showed a reduction of 0.4 points in spasticity (MAS), an increase in grip strength of 1.6 kg in power grip and 1.2 kg in pinch grip, and hand function improved by 6 points on the PDMS-2 scale. |

| 19 | Anticipatory and reactive mechanisms of postural control were investigated in children and youth with CP. The tools used included a swaying platform, AI, cross-correlations, EMG, 6MWT, and the GMFM-CM. | The IREX was used for VR-based training, consisting of a 32-inch screen, a computer, a video camera, and a green screen for computer-generated images. | Participants were divided into an intervention group (N = 5) and a control group (N = 6). The intervention group performed VR-based balance training for 60 min daily over 5 days. Measurements were taken the weekend before and after the intervention, with the control group measured one week apart. | No significant differences in postural control were observed between the intervention and control groups. |

| 20 | The Assisting Hand Assessment (AHA) was used as the primary outcome measure, while the Melbourne Assessment of Unilateral Hand Function (MUUL) and the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) were secondary measures. | The Hocoma Armeo Spring Pediatric, an exoskeleton combined with VR games, was used, along with a 1/16-inch aquaplast splint to restrict the unaffected limb during therapy. | The intervention took place over 2 weeks, with a total of 10 days and 6 h per day. The children wore the splint for 5 h and 30 min, using the exoskeleton for 30 min daily, and the remaining 30 min were dedicated to bimanual practice to incorporate newly learned unilateral skills into daily bimanual tasks. Measurements were taken before starting the intervention, immediately after, and 6 months after the intervention. | There was a significant improvement in bimanual performance (AHA) and satisfaction with performance (COPM), with a statistically significant improvement in unilateral function (MUUL), though not considered significant. Long-term effects persisted for 6 months after the intervention. |

| 21 | Gross motor function (GMFM-88) and spasticity level (MAS), static balance (SBT), muscle strength (LSUT and CUT), aerobic endurance (6MWT), and lower limb flexibility (SRT and MTT) were measured. | The virtual training used the Xbox 360 Kinect console, while traditional training used regular materials. | The intervention program involved golf training for 12 weeks, with 1 h sessions three days a week. In the first 2 weeks, basic golf movements were taught, and for the next 10 weeks, the group was split into two: one performed traditional golf training, and the other completed virtual golf training. Measurements were taken before and after the intervention. | Both training methods showed improvements in flexibility, muscle strength, aerobic endurance, and gross motor function, with no significant differences between the two types of training except for balance and lateral stepping tests. |

| 22 | Balance (PBS and Mini-BESTest), gross motor performance (GMFM-88), and daily functions (WeeFIM) were measured. | The Xbox 360 Kinect was used to play VR games, including Super Saver, Soccer, Volleyball, 20,000 Leaks, and Space Pop. | The intervention aimed to train balance and mobility, and participants were divided into two groups: the experimental group, which conducted VR games combined with physical therapy, and the control group, which only received physical therapy. The sessions lasted 60 min, 4 days a week for 6 weeks. Measurements were taken before, after, and 2 months after the 6-week intervention. | Measurements were taken before, 6 weeks after the intervention, and 2 months after the intervention. A significant improvement was observed in the Mini-BESTest, but there was no significant difference in motor performance or daily function between the experimental and control groups. The benefits were maintained after the 2-month follow-up. |

| 23 | Two measurements were taken: one before the intervention and another afterward, assessing gross motor function (GMFCS and GMFM). | A conventional exercise program and another using VR games with an Xbox 360 Kinect (Kinect Sports I, Kinect Joy Ride, and Kinect Adventures) were conducted. | Children were randomly divided into 2 groups of 15 (control and study groups). The control group completed a conventional exercise program for 60 min, 3 sessions per week for 3 months, while the study group performed the same conventional program along with 30 min of VR games per session. Measurements were taken before and after the intervention. | There were no significant differences in initial scores between the two groups. After the intervention, the study group showed a significant improvement in GMFM scores. Regarding GMFCS, there were no significant changes in either group, although the study group showed a significant difference between pre- and post-study scores. |

| 24 | The primary variable for hand function in bimanual activities was AHA, and secondary measures included BBT, JTTHF, and MFPT. The 6MWT gait evaluation was also performed. Questionnaires reported by parents included ABILHAND-Kids, ABILOCO-Kids, and ACTIVLIM-CP, with functional objectives measured by COPM. | A virtual REAtouch® device was used, designed to facilitate therapeutic decision-making and structure the intervention to apply motor skill learning principles. It features a 45-inch responsive screen with a frame that allows height and tilt angle adjustments depending on the task at hand. Participants interacted using “bases” or direct contact with their hands or tangible objects that matched the target bases. | Participants were assigned to either a control group, which followed the “usual” HABIT-ILE protocols, or a study group, which underwent the same HABIT-ILE but with the REAtouch® device used for half of the individual therapeutic time (41%). The intervention took place in a high-intensity day camp setting over 10–12 consecutive weekdays, totaling up to 90 h. Measurements were taken before, after, and 3 months after the intervention. | Both groups showed significant improvements in most outcome measures. The REAtouch® group was not inferior to the HABIT-ILE group in motor function and functional goals. Significant changes in questionnaires indicated the transfer of learning to daily life activities. The integration of the REAtouch® device into the HABIT-ILE camp was feasible and effective. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Velasco Aguado, J.; Espada, M.C.; Muñoz-Jiménez, J.; Ferreira, C.C.; Gámez-Calvo, L. Physical Exercise Interventions Using Virtual Reality in Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020189

Velasco Aguado J, Espada MC, Muñoz-Jiménez J, Ferreira CC, Gámez-Calvo L. Physical Exercise Interventions Using Virtual Reality in Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(2):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020189

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelasco Aguado, Javier, Mário C. Espada, Jesús Muñoz-Jiménez, Cátia C. Ferreira, and Luisa Gámez-Calvo. 2025. "Physical Exercise Interventions Using Virtual Reality in Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 2: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020189

APA StyleVelasco Aguado, J., Espada, M. C., Muñoz-Jiménez, J., Ferreira, C. C., & Gámez-Calvo, L. (2025). Physical Exercise Interventions Using Virtual Reality in Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(2), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020189