Patient Preferences or Provider Pressure? The Relationship Between Coercive Contraceptive Care and Preferred Contraceptive Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Independent Variable: Contraceptive Coercion

2.2.2. Dependent Variable: Preferred Contraceptive Use

2.2.3. Covariates

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

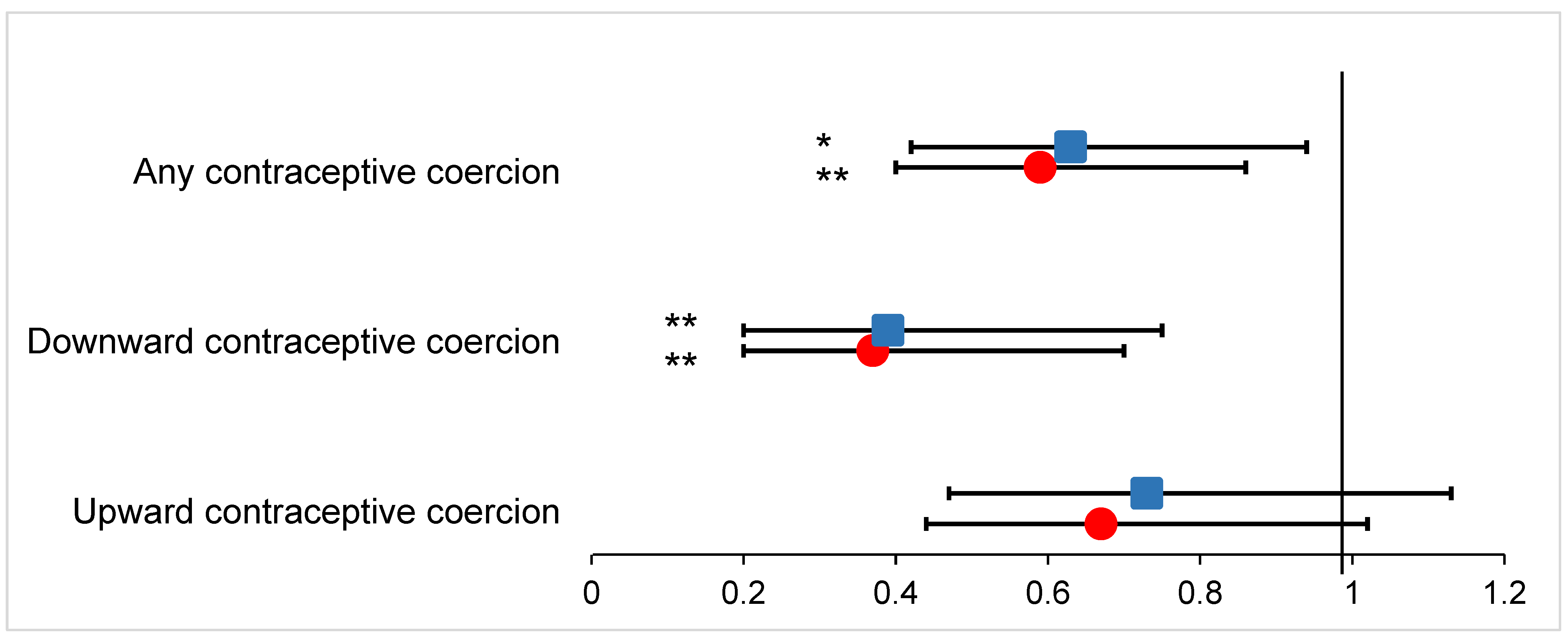

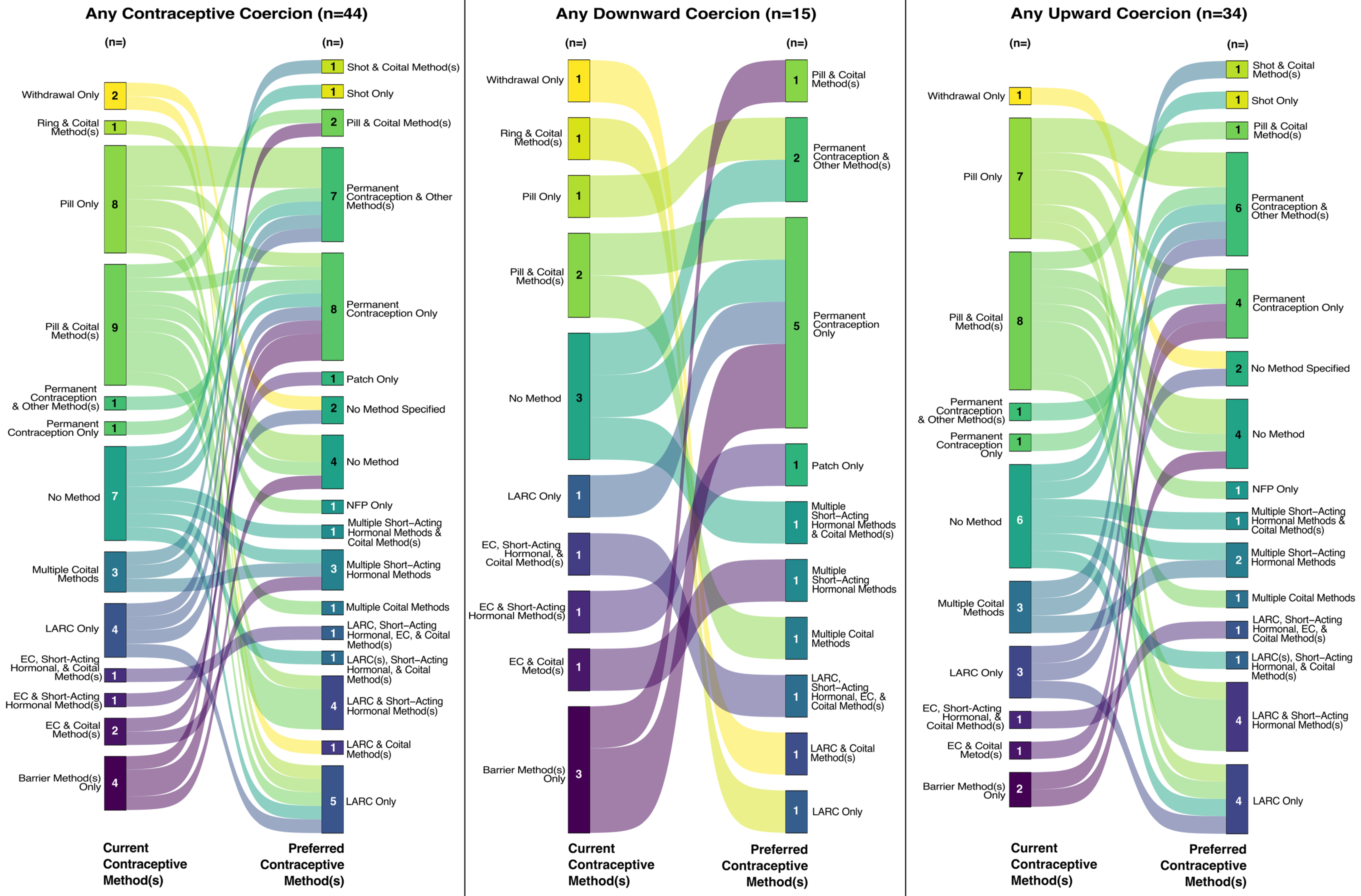

3.2. Coercion and Preferred Contraceptive Use

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swan, L.E.T.; Senderowicz, L.G.; Lefmann, T.; Ely, G.E. Health care provider bias in the Appalachian region: The frequency and impact of contraceptive coercion. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, L.E.T.; Cannon, L. Healthcare Provider-Based Contraceptive Coercion: Understanding, U.S. Patient Experiences and Describing Implications for Measurement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senderowicz, L. “I was obligated to accept”: A qualitative exploration of contraceptive coercion. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 239, 112531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, K.; Fuentes, L. The history of tiered-effectiveness contraceptive counseling and the importance of patient-centered family planning care. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, S873–S877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.M.; Fuentes, L.; Allina, A. Women or LARC First? Reproductive Autonomy and the Promotion of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Methods. Perspect. Sex Reprod. Health 2014, 46, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, L.N.; Karasek, D.; Ma, S.; Darney, P.; Deardorff, J.; Lahiff, M.; Grossman, D.; Foster, D.G. Contraceptive Features Preferred by Women at High Risk of Unintended Pregnancy. Perspect Sex Repro. Health 2012, 44, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amico, J.R.; Bennett, A.H.; Karasz, A.; Gold, M. “She just told me to leave it”: Women’s experiences discussing early elective IUD removal. Contraception 2016, 94, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, L.M.; Simon, M.A. Perceptions of Coercion, Discrimination and Other Negative Experiences in Postpartum Contraceptive Counseling for Low-income Minority Women. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2011, 22, 1387–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.A.; Kramer, R.D.; Ryder, K.M. Provider Bias in Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) Promotion and Removal: Perceptions of Young Adult Women. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1932–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, S.; Bumpus, M.; Luchowski, A. From uptake to access: A decade of learning from the ACOG LARC program. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, S866–S868 e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrero, S.; Nikolajski, C.; Rodriguez, K.L.; Creinin, M.D.; Arnold, R.M.; Ibrahim, S.A. “Everything I Know I Learned from My Mother...or Not”: Perspectives of African-American and White Women on Decisions About Tubal Sterilization. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimport, K.; Dehlendorf, C.; Borrero, S. Patient-provider conversations about sterilization: A qualitative analysis. Contraception 2017, 95, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.E.; White, K.; Hopkins, K.; McKinnon, S.; Shedlin, M.G.; Amastae, J.; Grossman, D. Frustrated Demand for Sterilization Among Low-Income Latinas in El Paso, Texas. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2012, 44, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanaugh, M.L.; Pliskin, E.; Hussain, R. Associations between unfulfilled contraceptive preferences due to cost and low-income patients’ access to and experiences of contraceptive care in the United States, 2015–2019. Contracept. X 2022, 4, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, L.E.T.; Vu, H.; Higgins, J.A.; Bui, L.M.; Malecki, K.; Green, T.L. Exploring financial stress and resource deprivation as barriers to preferred contraceptive use in Wisconsin in 2021. Contraception 2022, 115, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, A.; Lerma, K.; Sierra, G.; White, K. Barriers to Preferred Contraception Use in Mississippi. J. Women’s Health 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, K.L.; Potter, J.E.; White, K. Unsatisfied contraceptive preferences due to cost among women in the United States. Contracept. X 2020, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, A.M.; Wapman, M. Under (implicit) pressure: Young Black and Latina women’s perceptions of contraceptive care. Contraception 2017, 96, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palan, S.; Schitter, C. Prolific.ac—A subject pool for online experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2018, 17, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.E.; Stevenson, A.J.; Coleman-Minahan, K.; Hopkins, K.; White, K.; Baum, S.E.; Grossman, D. Challenging unintended pregnancy as an indicator of reproductive autonomy. Contraception 2019, 100, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.N.; Hellberg, S.N.; Hopkins, T.A.; Thompson, K.A.; Bruening, A.B.; Jones, A.C. Situating reproductive coercion in the sociocultural context: An ecological model to inform research, practice, and policy in the United States. J. Trauma Dissociation 2023, 24, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 18; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, L.J.; Foster, D.G.; Rocca, C.H. Comparing Prospective and Retrospective Reports of Pregnancy Intention in a Longitudinal Cohort of U.S. Women. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2020, 52, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, M.A.; Lundsberg, L.S.; Gariepy, A.M. A Multidimensional and Longitudinal Exploratory Study of the Stability of Pregnancy Contexts in the United States. Women’s Health Rep. 2024, 5, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, L.E.T. The impact of US policy on contraceptive access: A policy analysis. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossman, D.A.; Ruddy, J. Improving Patient-Provider Relationships to Improve Health Care. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 1417–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Mullins, C.D.; Novak, P.; Thomas, S.B. Personalized Strategies to Activate and Empower Patients in Health Care and Reduce Health Disparities. Health Educ. Behav. 2016, 43, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, L.E.T.; Cannon, L.M.; Lands, M.; Higgins, J.A.; Green, T.L. Coercion in contraceptive care: Differences based on racial/ethnic identity, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Contraception 2023, 127, 110232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senderowicz, L.; Bullington, B.W.; Sawadogo, N.; Tumlinson, K.; Langer, A.; Soura, A.; Zabré, P.; Sié, A. Assessing the Suitability of Unmet Need as a Proxy for Access to Contraception and Desire to Use It. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2023, 54, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender identity | |

| Cisgender woman | 1137 (94.9%) |

| Trans man assigned female at birth | 16 (1.3%) |

| Nonbinary assigned female at birth | 44 (3.7%) |

| Age, Mean (Standard Deviation) | 32.78 (8.08) |

| Education level | |

| High school or less | 141 (11.8%) |

| Associate degree or some college | 390 (32.6%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 444 (37.1%) |

| Graduate school | 222 (18.6%) |

| Health insurance status | |

| Not insured | 109 (9.1%) |

| Insured | 1088 (90.9%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 101 (8.4%) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 83 (6.9%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 182 (15.2%) |

| Non-Hispanic mixed race | 48 (4.0%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 783 (65.4%) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Bisexual | 245 (20.5%) |

| Heterosexual | 779 (65.1%) |

| Gay or lesbian | 53 (4.4%) |

| Asexual, pansexual, queer, questioning, or prefer to self-describe | 120 (10.0%) |

| Marital status | |

| Not married | 777 (64.9%) |

| Married | 420 (35.1%) |

| Time since last contraceptive counseling | |

| In the past year | 559 (46.7%) |

| 1–3 years | 412 (34.4%) |

| 4–6 years | 136 (11.4%) |

| 7 years or more | 90 (7.5%) |

| Coercion at Last Contraceptive Counseling | Total | Using Preferred Contraceptive Method(s) | Not Using Preferred Contraceptive Method(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Any coercion | |||

| No | 976 (81.5%) | 851 (87.2%) ** | 125 (12.8%) ** |

| Yes | 221 (18.5%) | 177 (80.1%) ** | 44 (19.9%) ** |

| Downward coercion | |||

| No | 1146 (95.7%) | 992 (86.6%) ** | 154 (13.4%) ** |

| Yes | 51 (4.3%) | 36 (70.6%) ** | 15 (29.4%) ** |

| Upward coercion | |||

| No | 1014 (84.7%) | 879 (86.7%) | 135 (13.3%) |

| Yes | 183 (15.3%) | 149 (81.4%) | 34 (18.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Swan, L.E.T.; Cannon, L.M.; Lands, M.; Zhao, I.H. Patient Preferences or Provider Pressure? The Relationship Between Coercive Contraceptive Care and Preferred Contraceptive Use. Healthcare 2025, 13, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020145

Swan LET, Cannon LM, Lands M, Zhao IH. Patient Preferences or Provider Pressure? The Relationship Between Coercive Contraceptive Care and Preferred Contraceptive Use. Healthcare. 2025; 13(2):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020145

Chicago/Turabian StyleSwan, Laura E. T., Lindsay M. Cannon, Madison Lands, and Iris Huimeng Zhao. 2025. "Patient Preferences or Provider Pressure? The Relationship Between Coercive Contraceptive Care and Preferred Contraceptive Use" Healthcare 13, no. 2: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020145

APA StyleSwan, L. E. T., Cannon, L. M., Lands, M., & Zhao, I. H. (2025). Patient Preferences or Provider Pressure? The Relationship Between Coercive Contraceptive Care and Preferred Contraceptive Use. Healthcare, 13(2), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020145