Wellbeing and Retirement in Europe: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

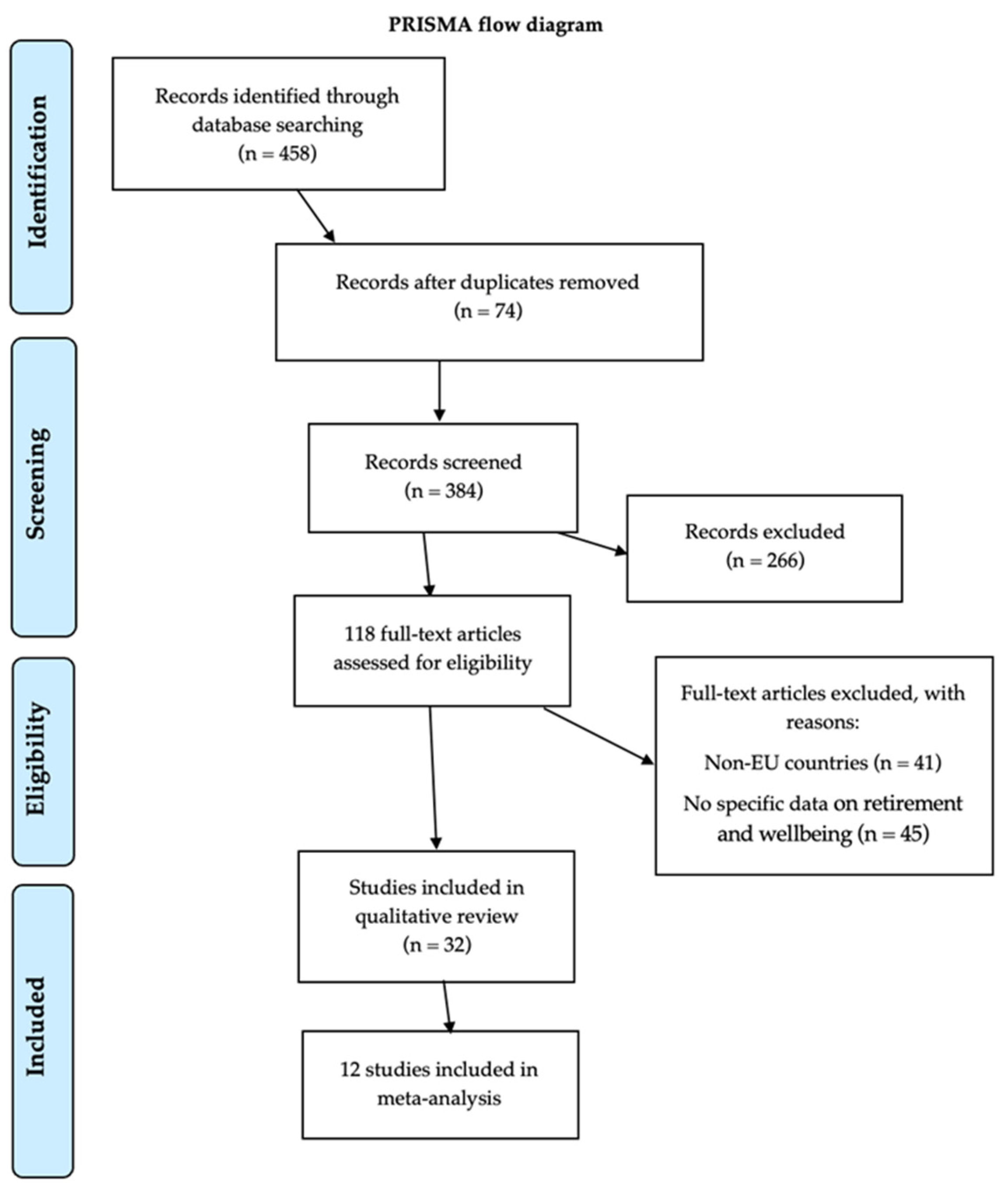

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Risk of Bias

3.2. Meta-Analysis

3.3. Study Description and Qualitative Analysis

3.3.1. Expectations Regarding Retirement

3.3.2. Preparation for Retirement

3.3.3. Family Relations and Grandparenting

3.3.4. Quality of Life and Satisfaction with Retirement

3.3.5. Health Consequences of Retirement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eurostat. Ageing Europe—Looking at the Lives of Older People in the EU; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pilehvari, A.; You, W.; Lin, X. Retirement’s impact on health: What role does social network play? Eur. J. Ageing 2023, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet Regional Health-Europe. Securing the future of Europe’s ageing population by 2050. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2023, 35, 100807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubicek, B.; Korunka, C.; Raymo, J.M.; Hoonakker, P. Psychological well-being in retirement: The effects of personal and gendered contextual resources. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henkens, K.; van Dalen, H.P.; Ekerdt, D.J.; Hershey, D.A.; Hyde, M.; Radl, J.; van Solinge, H.; Wang, M.; Zacher, H. What We Need to Know About Retirement: Pressing Issues for the Coming Decade. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M. Profiling retirees in the retirement transition and adjustment process: Examining the longitudinal change patterns of retirees’ psychological well-being. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeaton, D.; Barnes, H.; Vegeris, S. Does Retirement Offer a “Window of Opportunity” for Lifestyle Change? Views From English Workers on the Cusp of Retirement. J. Aging Health 2017, 29, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Shultz, K.S. Employee retirement: A review and recommendations for future investigation. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, K.S.; Wang, M. Psychological perspectives on the changing nature of retirement. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, M. Does quality of work life affect men and women’s retirement planning differently? Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2008, 3, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health. Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. 2024. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Weziak-Bialowolska, D.; Bialowolski, P.; Niemiec, R.M. Character strengths and health-related quality of life in a large international sample. J. Res. Personal. 2023, 103, 104338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowska-Kmon, A.; Łątkowski, W.; Rynko, M. Informal care and subjective well-being among older adults in selected European countries. Ageing Int. 2023, 48, 1163–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adena, M.; Hamermesh, D.; Myck, M.; Oczkowska, M. Home alone: Widows’ well-being and time. J. Happiness Stud. 2023, 24, 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpino, B.; Gómez-Léon, M. Consequences on depression of combining grandparental childcare with other caregiving roles. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bađun, M.; Smolić, Š. Predictors of early retirement intentions in Croatia. Društvena Istraživanja 2018, 27, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.; Brandt, M.; Kneip, T. The role of parenthood for life satisfaction of older women and men in Europe. J. Happiness Stud. 2023, 24, 275–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantisano, G.; Depolo, M.; León, J.; Domínguez, J. Empleo puente y bienestar personal de los jubilados. Un modelo de ecuaciones estructurales con una muestra europea probabilística [Bridge employment and personal well-being of retirees. A structural equation model with a probabilistic European sample]. Psicothema 2009, 21, 280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, M.F.; Brandão, M.P. Having type 2 diabetes does not imply retirement before age 65 in Europe. J. Popul. Ageing 2022, 15, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheval, B.; Maltagliati, S.; Saoudi, I.; Fessler, L.; Farajzadeh, A.; Sieber, S.; Cullati, S.; Boisgontier, M.P. Physical activity mediates the effect of education on mental health trajectories in older age. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 336, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielsbacka, M.; Tanskanen, A.; Coall, D.; Jokela, M. Grandparental childcare, health and well-being in Europe: A within individual investigation of longitudinal data. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 230, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingemans, E.; Henkens, K. Working after retirement and life satisfaction: Cross-national comparative research in Europe. Res. Aging 2019, 41, 648–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djundeva, M.; Dykstra, P.A.; Fokkema, T. Is living alone “aging alone”? Solitary living, network types, and well-being. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2019, 74, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hank, K.; Vagner, M. Parenthood, marital status, and well-being in later life: Evidence from SHARE. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, E. Subjective well-being and retirement: Analysis and policy recommendations. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, H.; Levinsky, M. The interplay of personality traits and social network characteristics in the subjective well-being of older adults. Res. Aging 2023, 45, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Agostino, D.; Stone, A.; Schneider, S.; Koskinen, S.; Leonardi, M.; Naidoo, N.; Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B.; Haro, J.M.; Miret, M.; Kowal, P.; et al. Are retired people higher in experiential wellbeing than working older adults? A time use approach. Emotion 2020, 20, 1411–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okely, J.; Cooper, C.; Gale, C. Well-being and arthritis incidence: The survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. Ann. Behav. Med. 2016, 50, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okely, J.; Shaheen, S.; Weiss, A.; Gale, C. Well-being and chronic lung disease incidence: The survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okely, J.; Weiss, A.; Gale, C. The interaction between individualism and well-being in predicting mortality: Survey of health ageing and retirement in Europe. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, J.; Ponomarenko, V. Pension insecurity and well-being in Europe. J. Soc. Policy 2017, 46, 517–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomäki, L. Does it matter how you retire? Old-age retirement routes and subjective economic well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 142, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploubidis, G.B.; Grundy, E. Later-life mental health in Europe: A country-level comparison. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 64B, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, V. Cumulative disadvantages of non-employment and non-standard work for career patterns and subjective well-being in retirement. Adv. Life Course Res. 2016, 30, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, V.; Leist, A.K.; Chauvel, L. Increases in well-being in the transition to retirement for the unemployed: Catching up with formerly employed persons. Ageing Soc. 2019, 39, 254–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Pérez, F.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, V.; Molina-Martínez, M.A.; Fernandez-Mayoralas, G.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, D.; Rojo-Abuin, J.M.; Ayala, A.; Rodriguez-Blazquez, C.; Calderon-Larrañaga, A.; Ribeiro, O.; et al. Active ageing profiles among older adults in Spain: A multivariate analysis based on SHARE study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, J.; Wahrendorf, M.; Knesebeck, O.; Jurges, H.; Borsch-Supan, A. Quality of work, well-being, and intended early retirement of older employees—Baseline results from the SHARE study. Eur. J. Public Health 2007, 17, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohier, L. Do involuntary longer working careers reduce well-being? Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 14, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohier, L.; van Ootegem, L.; Verhofstadt, E. Well-being during the transition from work to retirement. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohier, L.; Defloor, B.; Van Ootegem, L.; Verhofstadt, E. Determinants of the willingness to retire of older workers in Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 164, 1017–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambellini, E. Exploring the relationship between working history, retirement transition and women’s life satisfaction. Ageing Soc. 2023, 43, 1754–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahrendorf, M.; Siegrist, J. Are changes in productive activities of older people associated with changes in their well-being? Results of a longitudinal European study. Eur. J. Ageing 2010, 7, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weziak-Białowolska, D.; Skiba, R.; Białowolski, P. Longitudinal reciprocal associations between volunteering, health and well-being: Evidence for middle-aged and older adults in Europe. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, W.; van Wijngaarden, J.D.H.; Huijsman, R.; Buljac-Samardžić, M. The Effect of Long-Term (Im)balance of Giving Versus Receiving Support With Nonrelatives on Subjective Well-Being Among Home-Dwelling Older People. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2024, 79, gbad198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, D.C. The decision to retire early: A review and conceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, S.; Ruokolainen, M.; Holman, D. Challenges and practices in promoting (ageing) employees’ working careers in the health care sector: Case studies from Germany, Finland, and the UK. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahdenperä, M.; Virtanen, M.; Myllyntausta, S.; Pentti, J.; Vahtera, J.; Stenholm, S. Psychological Distress During the Retirement Transition and the Role of Psychosocial Working Conditions and Social Living Environment. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2022, 77, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartanto, A.; Sim, L.; Lee, D.; Majeed, N.M.; Yong, J.C. Cultural contexts differentially shape parents’ loneliness and wellbeing during the empty nest period. Commun. Psychol. 2024, 2, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambra, C.; Eikemo, T.A. Welfare state regimes, unemployment and health: A comparative study of the relationship between unemployment and self-reported health in 23 European countries. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Hartig, T.; Martin, L.; Pahl, S.; van den Berg, A.E.; Wells, N.M.; Costongs, C.; Dzhambov, A.M.; Elliott, L.R.; Godfrey, A.; et al. Nature-based biopsychosocial resilience: An integrative theoretical framework for research on nature and health. Environ. Int. 2023, 181, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NIH Quality Assessment Criteria | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | Quality Rating (Good, Fair, Poor) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abramowska-Kmon, Łątkowski, and Rynko (2023) [14] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | NR | Fair |

| Adena, Hamermesh, Myck, and Oczkowska (2023) [15] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Arpino and Gómez-Léon (2020) [16] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Bađun and Smolic (2018) * [17] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | NR | Fair |

| Bauer, Brandt, and Kneip (2022) [18] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Cantisano, Depolo, León, and Domínguez (2009) * [19] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Cardoso and Brandão (2022) * [20] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Cheval et al. (2023) [21] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Danielsbacka, Tanskanen, Coall, and Jokela (2019) [22] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | NR | Fair |

| Dingemans and Henkens (2019) * [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Djundeva, Dykstra, and Fokkema (2019) [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | NR | Fair |

| Hank and Vagner (2013) [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | NR | Fair |

| Horner (2014) * [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Litwin and Levinsky (2023) [27] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | NR | Fair |

| Moreno-Agostino et al. (2020) * [28] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Okely, Cooper, and Gale (2016) [29] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Okely, Shaheen, Weiss, and Gale (2017) [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Okely, Weiss, and Gale (2018) [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Olivera and Ponomarenko (2017) [32] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | NR | Fair |

| Palomäki (2019) * [33] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | NR | Fair |

| Ploubidis and Grundy (2009) [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Ponomarenko (2016) * [35] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Ponomarenko, Leist, and Chauvel (2019) * [36] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Rojo-Perez et al. (2022) [37] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Siegrist, Wahrendorf, Knesebeck, Jurges, and Borsch-Supan (2006) [38] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Sohier (2019) * [39] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Sohier, van Ootegem, and Verhofstadt (2021) * [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Sohier, Defoor, Van Ootegem, and Verhofstadt (2022) [41] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Tambellini (2023) * [42] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Wahrendorf and Siegrist (2010) [43] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Good |

| Weziak-Bialowolska, Skiba, and Bialowolski (2024) [44] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Xia, van Wijngaarden, Huijsman, and Buljac-Samardžić (2024) [45] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Publication Identification | European Countries | Type of Design | Age Group | Sample Size | Variables Involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abramowska-Kmon, Łątkowski, and Rynko (2023) [14] | Austria, Germany, Sweden, Spain, Italy, France, Denmark, Greece, Switzerland, Belgium, Czechia, Poland, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovenia, Estonia, and Croatia. | Cross-sectional | 50 years and older | 30,179 participants (53.8% women) | Receiving informal care, subjective wellbeing |

| Adena, Hamermesh, Myck, and Oczkowska (2023) [15] | Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | 50 years and older | 3056 participants (10.3% widowed) | Widowed and wellbeing, such as mental health and life satisfaction |

| Arpino and Gómez-Léon (2020) [16] | Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland | Retrospective cohort | Aged between 50 and 84 years old | 11,796 participants (57.5% women) | Grandchild care, depressive symptoms, and wellbeing |

| Bađun and Smolić (2018) * [17] | Croatia | Cross-sectional | 50 years and older | 432 participants (40.4% women) | Early retirement wellbeing, health status |

| Bauer, Brandt, and Kneip (2022) [18] | Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | 50 to 85 years old | 59,864 participants (55.9% women) | Parenthood and wellbeing |

| Cantisano, Depolo, León, and Domínguez (2009) * [19] | Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | 50 years and older (mean age = 63 years old) | 650 (47% women) | Bridge employment activity, job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and quality of life in retirement |

| Cardoso and Brandão (2022) * [20] | Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | Aged between 51 and 64 years old | 10,794 participants (60% women) | Type 2 diabetes, retirement, wellbeing |

| Cheval et al. (2023) [21] | Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland—SHARE wave 1 to wave 8 (2004 to 2019) | Retrospective cohort | 50 years and older | 54,818 participants (55% women) | Educational attainment, quality of life wellbeing, physical activity, and depression symptoms |

| Danielsbacka, Tanskanen, Coall, and Jokela (2019) [22] | Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland | Retrospective cohort | Aged between 50 and 89 years old | 41,713 participants (60.1% women) | Grandparental childcare and wellbeing, including difficulties with activities of daily living, depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, and meaning of life |

| Dingemans and Henkens (2019) * [23] | Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland | Retrospective cohort | Aged between 60 and 75 years old | 54,156 participants (53% women) | Working after retirement, wellbeing, and pension income |

| Djundeva, Dykstra, and Fokkema (2019) [24] | Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. | Cross-sectional | 50 years and older | 9904 participants | Social networks and subjective wellbeing, such as life satisfaction, satisfaction with social network, and depression |

| Hank and Vagner (2013) [25] | Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | 65 years old and over | More than 9000 participants (54.2% women) | Parenthood, marital status, and wellbeing in later life |

| Horner (2014) * [26] | Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. | Cross-sectional | Aged between 50 and 70 years old | 18,345 participants (only men) | Subjective wellbeing and retirement |

| Litwin and Levinsky (2023) [27] | Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | Aged 50 years and over | 35,145 participants (58% women) | Perceived quality of life, wellbeing, depressive symptoms |

| Moreno-Agostino et al. (2020) * [28] | Finland, Poland, and Spain | Cross-sectional | Aged 50 years and over | 2222 participants (46.95% women) | Experiential wellbeing, retirement |

| Okely, Cooper, and Gale (2016) [29] | Denmark, Sweden, Austria, France, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, and Greece | Cross-sectional | Aged 50 years and over | 10,530 participants (51.66% women) | Wellbeing and arthritis incidence |

| Okely, Shaheen, Weiss, and Gale (2017) [30] | Denmark, Sweden, Austria, France, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, and Greece | Cross-sectional | Aged 50 years and over | 12,246 participants (55.1% females) | Wellbeing and chronic lung disease incidence, retirement |

| Okely, Weiss, and Gale (2018) [31] | Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain | Cross-sectional | Aged 50 years and over | 13,596 participants (54.5% females) | Wellbeing, self-rated health |

| Olivera and Ponomarenko (2017) [32] | Austria, Germany, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | Aged between 50 and 75 years old | 15,389 participants (50.5% women) | Pension insecurity and wellbeing |

| Palomäki (2019) * [33] | Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Spain, Finland, France, Hungary, Ireland, Iceland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden, Slovenia, Slovakia, and the United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | Aged 55 years and over | 26,680 participants (58% women) | Subjective economic wellbeing, retirement |

| Ploubidis and Grundy (2009) [34] | Denmark, Sweden, Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, and Greece | Cross-sectional | 50 years and over | 13,498 participants (54.2% women) | Depression and wellbeing |

| Ponomarenko (2016) * [35] | Austria, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, France, Denmark, Greece, Switzerland, Belgium, Czech Republic, and Poland | Retrospective cohort | Aged 65 years and over | 8098 participants (48.3% women) | Cumulative disadvantages of non-employment, non-standard work, retirement, and wellbeing |

| Ponomarenko, Leist, and Chauvel (2019) * [36] | Austria, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, France, Denmark, Switzerland, Belgium, Czechia, and Poland | Cross-sectional | Aged between 50 and 70 years old | 2163 participants | Wellbeing, transition to retirement, employed, unemployed or economically inactive |

| Rojo-Perez et al. (2022) [37] | Spain | Cross-sectional | Aged 50 years and over | 5566 participants (53.8% women) | Health, lifelong learning, quality of life, wellbeing |

| Siegrist, Wahrendorf, Knesebeck, Jurges, and Borsch-Supan (2007) [38] | Austria, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, France, Denmark, Greece, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | 65 years old or less | 6836 participants (48.5% women) | Quality of work, wellbeing, and intended early retirement of older employees |

| Sohier (2019) * [39] | Denmark, Sweden, Belgium, Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | Aged between 50 and 70 years old | 16,667 participants | Working at older age, wellbeing |

| Sohier, van Ootegem, and Verhofstadt (2021) * [40] | Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Spain, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | Aged between 50 and 70 years old | 38,344 participants | Life satisfaction, agency-freedom, wellbeing |

| Sohier, Defloor, van Ootegem, and Verhofstadt (2022) [41] | Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | Aged 50 and over | 8410 participants | Personal facts, willingness to retire, wellbeing |

| Tambellini (2023) * [42] | Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland | Cross-sectional | Aged 50 and over | 2877 participants (100% women) | Transition to retirement and wellbeing |

| Wahrendorf and Siegrist (2010) [43] | Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Austria, Italy, Spain, and Greece | Cross-sectional | 50 and over | 10,309 participants (53.5% women) | Productive activities and wellbeing |

| Weziak-Bialowolska, Skiba, and Bialowolski (2024) [44] | Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the Netherlands | Prospective cohort | 50 and over | 19,821 participants (59.29% women) | Voluntary and/or charity activities and cognitive impairment, daily life functioning, physical health, wellbeing |

| Xia, van Wijngaarden, Huijsman, and Buljac-Samardžić (2024) [45] | Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland | Retrospective cohort | 60 and over | 4650 participants (65.16% women) | Support balance and subjective wellbeing, including depression, life satisfaction, and quality of life |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teques, A.P.; Carreiro, J.; Duarte, D.; Teques, P. Wellbeing and Retirement in Europe: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020100

Teques AP, Carreiro J, Duarte D, Teques P. Wellbeing and Retirement in Europe: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(2):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020100

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeques, Andreia P., Joana Carreiro, Daniel Duarte, and Pedro Teques. 2025. "Wellbeing and Retirement in Europe: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 2: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020100

APA StyleTeques, A. P., Carreiro, J., Duarte, D., & Teques, P. (2025). Wellbeing and Retirement in Europe: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Healthcare, 13(2), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13020100