Health Information Seeking and Behavior in the Korean Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Background

- Where (information source), what (search term), and how (device and frequency) did consumers obtain health-related information during the COVID-19 period?

- How did the search for health information found in this way affect actual health behavior?

- By verifying these research questions, we intend to identify consumers’ health information search behavior due to the COVID-19 pandemic and use it as basic data for predicting their post-pandemic behavior.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Measures

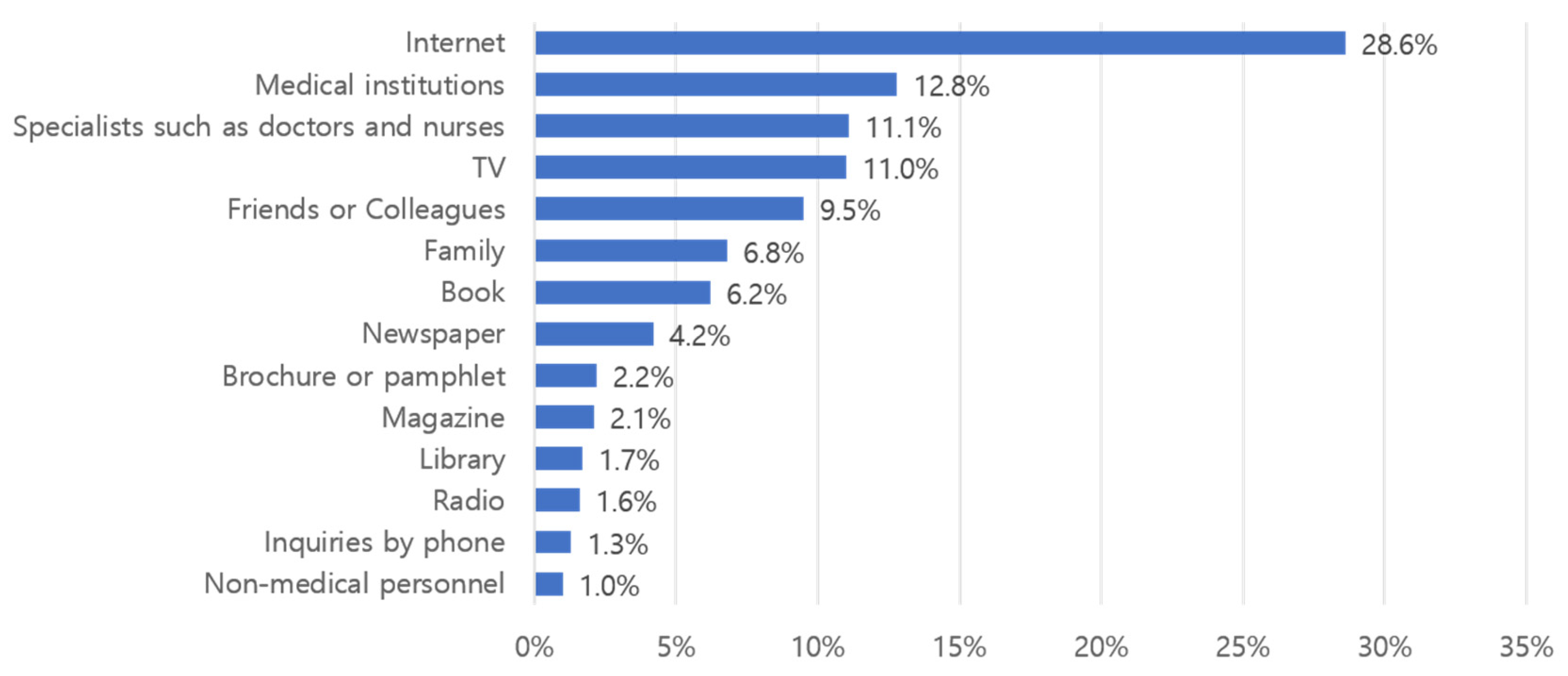

2.4. Information Sources

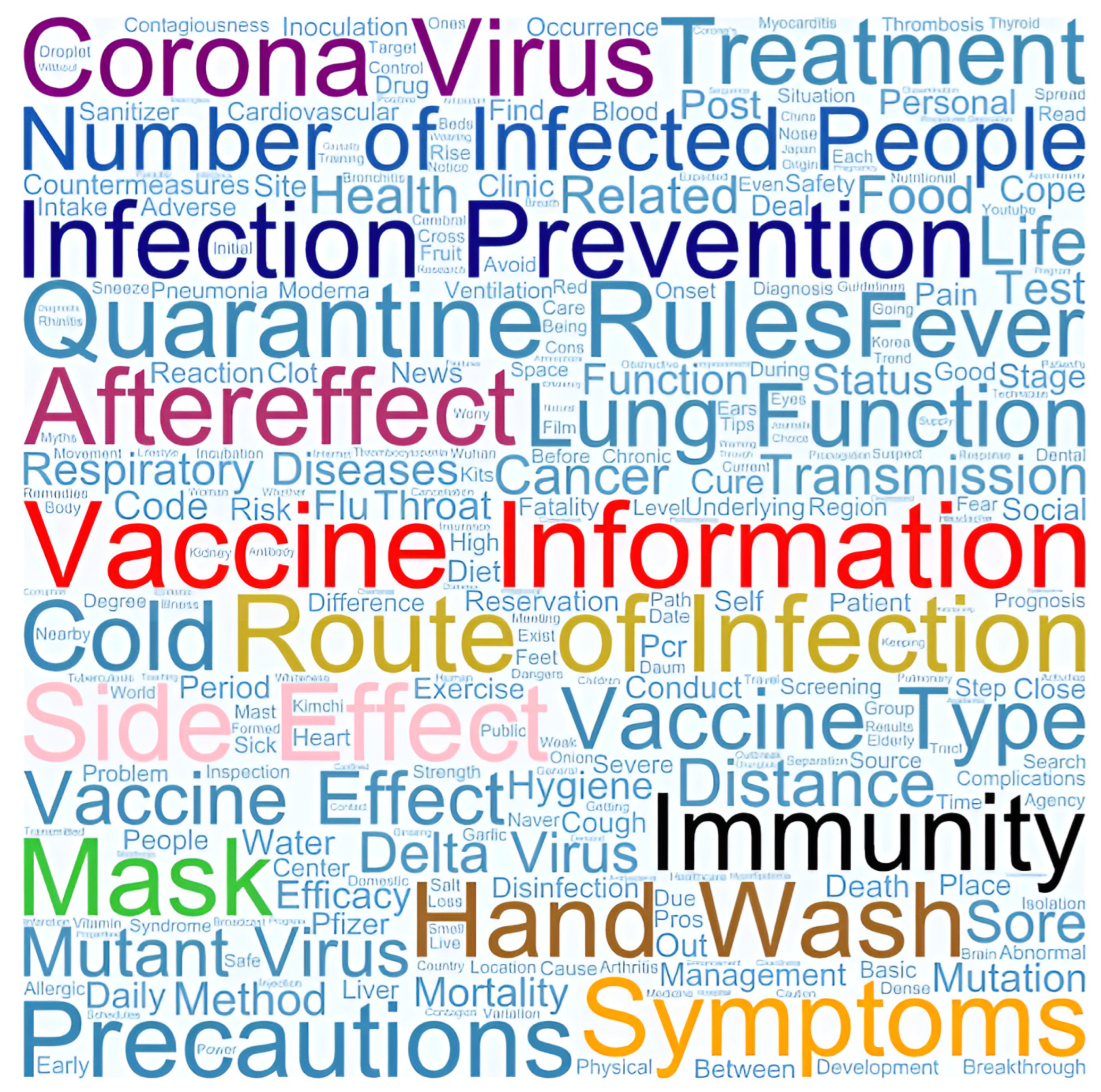

2.5. Search Terms

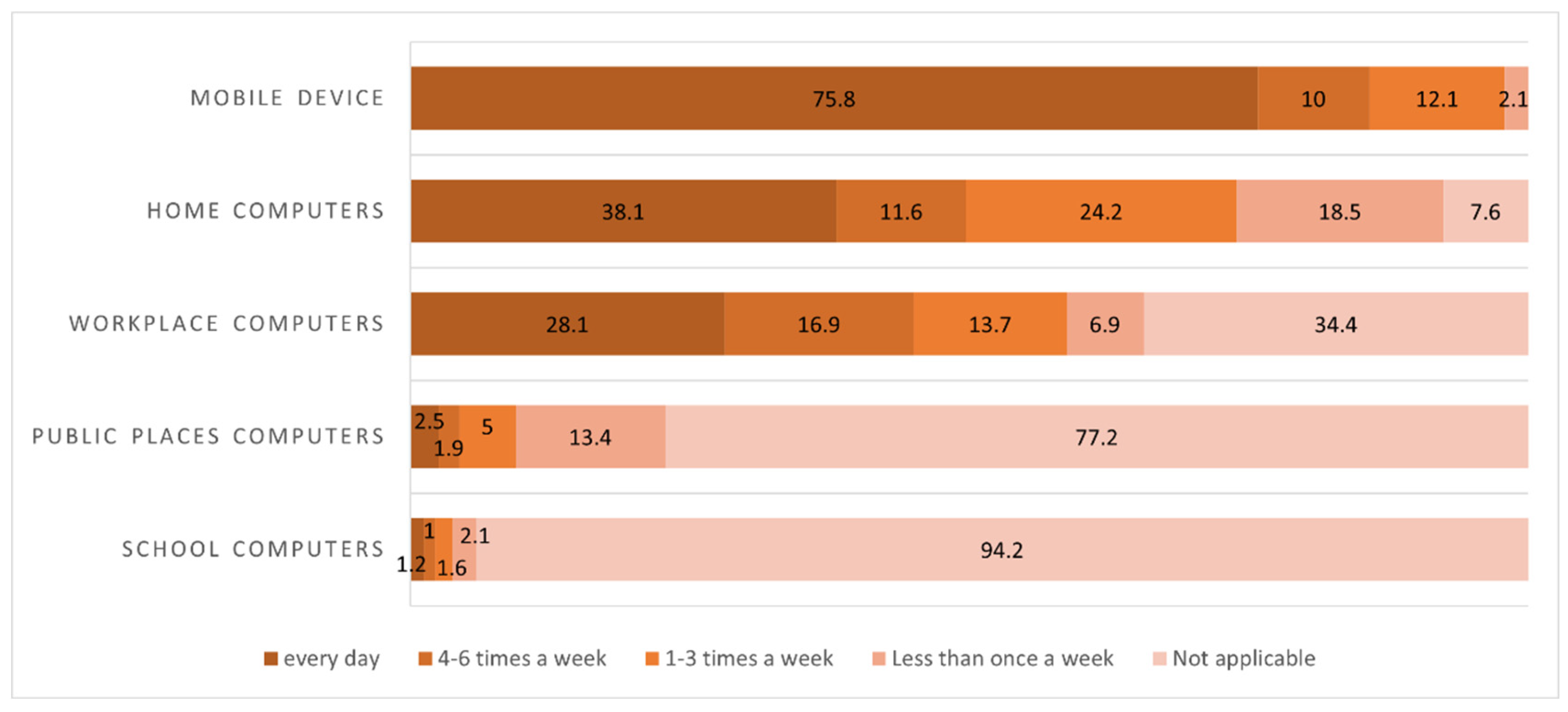

2.6. Device and Frequency

2.7. Information–Motivation–Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

3.2. Health Information-Seeking Behaviors

3.2.1. Information Source

3.2.2. Search Terms

3.2.3. Device and Frequency

3.3. Information–Motivation–Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model

3.4. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IMB | Information–Motivation–Behavior skills |

| K-HINTS | Korean version of the Health Information National Trend Survey |

| HINTS | Health Information National Trend Survey |

| ICT | Information and Communications Technologies |

References

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Vaishya, R. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2020, 10, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Fan, J.; Basnyat, I.; Hu, B. Online health information seeking using “#COVID-19 patient seeking help” on Weibo in Wuhan, China: Descriptive study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, T.; Ju, I.; Ohs, J.; Hinsley, A.; Muzumdar, J. EPH35 information seeking and preventive behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Value Health 2022, 25, S441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, I.J.; Aguolu, O.G.; Kobara, Y.M.; Razavi, R.; Akpan, A.A.; Shanker, M. Association between what people learned about COVID-19 using web searches and their behavior toward public health guidelines: Empirical infodemiology study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H. Concerns Rise Over Summer COVID-19 Wave. The Korea Herald. 2024. Available online: https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20240812050586 (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Liu, Z.W. Research progress and model construction for online health information seeking behavior. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 2021, 6, 706164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, H.N.; McDaniels-Davidson, C.; Nodora, J.; Madanat, H. Profiles of a health information–seeking population and the current digital divide: Cross-sectional analysis of the 2015–2016 California health interview survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e11931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalankesh, L.R.; Mohammadian, E.; Ghalandari, M.; Delpasand, A.; Aghayari, H. Health Information Seeking Behavior (HISB) among the university students. Front. Health Inform. 2019, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Pang, Y.; Liu, L.S. Online health information seeking behavior: A systematic review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, S.; Eldredge, C.; Sanders, R. Health information seeking behaviors on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic among American social networking site users: Survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e29802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Jeong, G. Characteristics of the measurement tools for assessing health information–seeking behaviors in nationally representative surveys: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Q. Social media use, eHealth literacy, disease knowledge, and preventive behaviors in the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional study on Chinese netizens. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.W.; Lu, W.H.; Ko, N.Y.; Chen, Y.L.; Li, D.J.; Chang, Y.P.; Yen, C.F. COVID-19-related information sources and the relationship with confidence in people coping with COVID-19: Facebook survey study in Taiwan. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute at the National Health Institutes. Health Information National Trend Survey. 2022. Available online: https://hints.cancer.gov/data/survey-instruments.aspx (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Fisher, J.D.; Fisher, W.A.; Amico, K.R.; Harman, J.J. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006, 25, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, J.D.; Fisher, W.A. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 111, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjahjadi, B.; Soewarno, N.; Adibah Wan Ismail, W.; Kustiningsih, N.; Nasihatun Nafidah, L. Community behavioral change and management of COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Indonesia. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 2023, 35, 102451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yao, L.; Zhou, L.; Yuan, F.; Zhong, X. Factors influencing health behaviours during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China: An extended information-motivation-behaviour skills model. Public Health 2020, 185, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Ahn, S. Classifications, changes, and challenges of online health information seekers during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wordart. Available online: https://wordart.com (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Cheung, G.W.; Lau, R.S. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 296–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 9781462551910. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Science and ICT. Results of the 2021 Internet Usage Survey. 2022. Available online: https://www.msit.go.kr/bbs/view.do?sCode=user&bbsSeqNo=79&nttSeqNo=3173463 (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Alzghaibi, H. People behavioral during health information searching in COVID-19 era: A review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1166639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Tighe, E.L.; Feinberg, I. The dispersion of health information–seeking behavior and health literacy in a state in the Southern United States: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e34708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilian, M.; Kakaei, H.; Nourmoradi, H.; Bakhtiyari, S.; Mazloomi, S.; Mirzaei, A. Health information seeking behaviors related to COVID-19 among young people: An online survey. Int. J. High. Risk Behav. Addict. 2021, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadaczynski, K.; Okan, O.; Messer, M.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Rosário, R.; Darlington, E.; Rathmann, K. Digital health literacy and web-based information-seeking behaviors of university students in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubb, C.; Foran, H.M. Online health information seeking by parents for their children: Systematic review and agenda for further research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Han, P.; Wang, J.; Shahzad, F. Digital pathways to healthcare: A systematic review for unveiling the trends and insights in online health information-seeking behavior. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1497025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G. More than we chat: Examining WeChat users’ vaccine-related health information seeking during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Media Res. 2022, 18, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guan, H.; Hao, R.; Liu, W. The impact of internet health information seeking on COVID-19 vaccination behavior in China. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Hao, X.; Guo, M.; Deng, J.; Li, L. A study of Chinese college students’ COVID-19-related information needs and seeking behavior. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 73, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Kong, H. Online health information seeking: A review and meta-analysis. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 1163–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Participants |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 45.0 (13.6) |

| Age (years), n (%) | |

| 19–39 | 368 (36.3) |

| 40–59 | 452 (44.6) |

| >60 | 194 (19.1) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 515 (50.8) |

| Female | 499 (49.2) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Elementary and middle school graduate | 10 (1.0) |

| High school graduate | 166 (16.4) |

| University/college student | 51 (5.0) |

| University/College graduate | 652 (64.3) |

| Graduate school student | 19 (1.9) |

| Grad school graduate and above | 116 (11.4) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 309 (30.5) |

| Married | 649 (64.0) |

| Divorced | 35 (3.5) |

| Widowed | 17 (1.7) |

| Separated and cohabiting | 4 (0.4) |

| Family income, n (%) | |

| <KRW 1 million | 43 (4.2) |

| KRW 1 million~KRW 2 million | 77 (7.6) |

| KRW 2 million~KRW 5 million | 468 (46.2) |

| KRW 5 million~KRW 10 million | 350 (34.5) |

| <KRW 10 million | 76 (7.5) |

| Variable | Information | Motivation | Behavioral Skills | Behavior Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information | ||||

| r | 1 | 0.141 | 0.170 | 0.236 |

| p value | - | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Motivation | ||||

| r | 0.141 | 1 | 0.143 | 0.131 |

| p value | <0.001 | - | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Behavioral Skills | ||||

| r | 0.170 | 0.143 | 1 | 0.138 |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | - | <0.001 |

| Behavior Changes | ||||

| r | 0.236 | 0.131 | 0.138 | 1 |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | - |

| Mean | 2.79 | 2.91 | 12.7130 | 1.6036 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.707 | 0.571 | 1.87557 | 1.11378 |

| Skewness | −0.104 | −0.326 | 0.098 | −0.122 |

| Kurtosis | −0.272 | 0.905 | 0.609 | −1.339 |

| Minimum | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Maximum | 4 | 4 | 16 | 3 |

| Variable | Mean | S.E. | C.R | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information | 2.794 | 0.022 | 125.890 a | ||

| Motivation | 2.906 | 0.018 | 162.123 a | ||

| B | β | S.E. | C.R | ||

| Behavioral Skills | item 1 | 1.000 | 0.815 | - | - |

| item 2 | 0.986 | 0.852 | 0.033 | 29.455 a | |

| item 3 | 0.942 | 0.744 | 0.037 | 25.170 a | |

| item 4 | 0.920 | 0.801 | 0.033 | 27.563 a | |

| Behavior Changes | item 1 | 1.000 | 0.485 | - | - |

| item 2 | 1.593 | 0.769 | 0.161 | 9.916 a | |

| item 3 | 1.129 | 0.558 | 0.106 | 10.631 a | |

| Correlation | B | β | S.E. | C.R | |

| Information ↔ Motivation | 0.057 | 0.141 | 0.013 | 4.428 a | |

| Information ↔ Behavioral Skills | 0.057 | 0.178 | 0.011 | 5.217 a | |

| Information ↔ Behavior Changes | 0.045 | 0.267 | 0.007 | 6.071 a | |

| Motivation ↔ Behavioral Skills | 0.040 | 0.154 | 0.009 | 4.536 a | |

| Motivation ↔ Behavior Changes | 0.023 | 0.167 | 0.006 | 4.146 a | |

| Behavioral Skills ↔ Behavior Changes | 0.019 | 0.176 | 0.005 | 4.094 a | |

| Model fit index | χ2 = 41.814, df = 23, p = 0.010, TLI = 0.989, CFI = 0.993, RMSEA = 0.028 | ||||

| Path | B | β | S.E. | C.R. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information → Behavioral Skills | 0.103 | 0.159 | 0.021 | 4.802 b | |

| Information → Behavioral Changes | 0.078 | 0.230 | 0.014 | 5.537 b | |

| Motivation → Behavioral Skills | 0.105 | 0.131 | 0.027 | 3.968 b | |

| Motivation → Behavioral Changes | 0.049 | 0.117 | 0.016 | 3.051 a | |

| Behavioral Skills → Behavioral Changes | 0.062 | 0.117 | 0.022 | 2.860 a | |

| Path | Total effect | Direct effect | Mediated effect | Indirect confidence interval | |

| Information → Behavioral Skills → Behavioral Changes | 0.248 | 0.230 | 0.019 | 0.009–0.036 a | |

| Motivation → Behavioral Skills → Behavioral Changes | 0.133 | 0.117 | 0.015 | 0.006–0.032 a | |

| Model fit index | χ2 = 41.814, df = 23, | p = 0.010, TLI = 0.989, CFI = 0.993, RMSEA = 0.028 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, H.; Jin, M.; Park, B. Health Information Seeking and Behavior in the Korean Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2539. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192539

Choi H, Jin M, Park B. Health Information Seeking and Behavior in the Korean Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2539. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192539

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Hanna, Meiling Jin, and Byungsun Park. 2025. "Health Information Seeking and Behavior in the Korean Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2539. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192539

APA StyleChoi, H., Jin, M., & Park, B. (2025). Health Information Seeking and Behavior in the Korean Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare, 13(19), 2539. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192539