Health-Related Quality of Life Among High-Risk Pregnant Women Hospitalized in a Maternal-Fetal Intensive Care Unit: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Demographic Information

2.3.2. Social Support

2.3.3. Marital Intimacy

2.3.4. Antenatal Depression

2.3.5. Self-Care Behavior

2.3.6. Perceived Health Condition

2.3.7. Fetal Attachment

2.3.8. HRQoL

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Information of Participants

3.2. Descriptive Statistics, Multicollinearity, and Normality of Measured Variables

3.3. Test of the Hypothetical Model

3.3.1. Reliability and Validity of Measures

3.3.2. Goodness of Fit of the Model

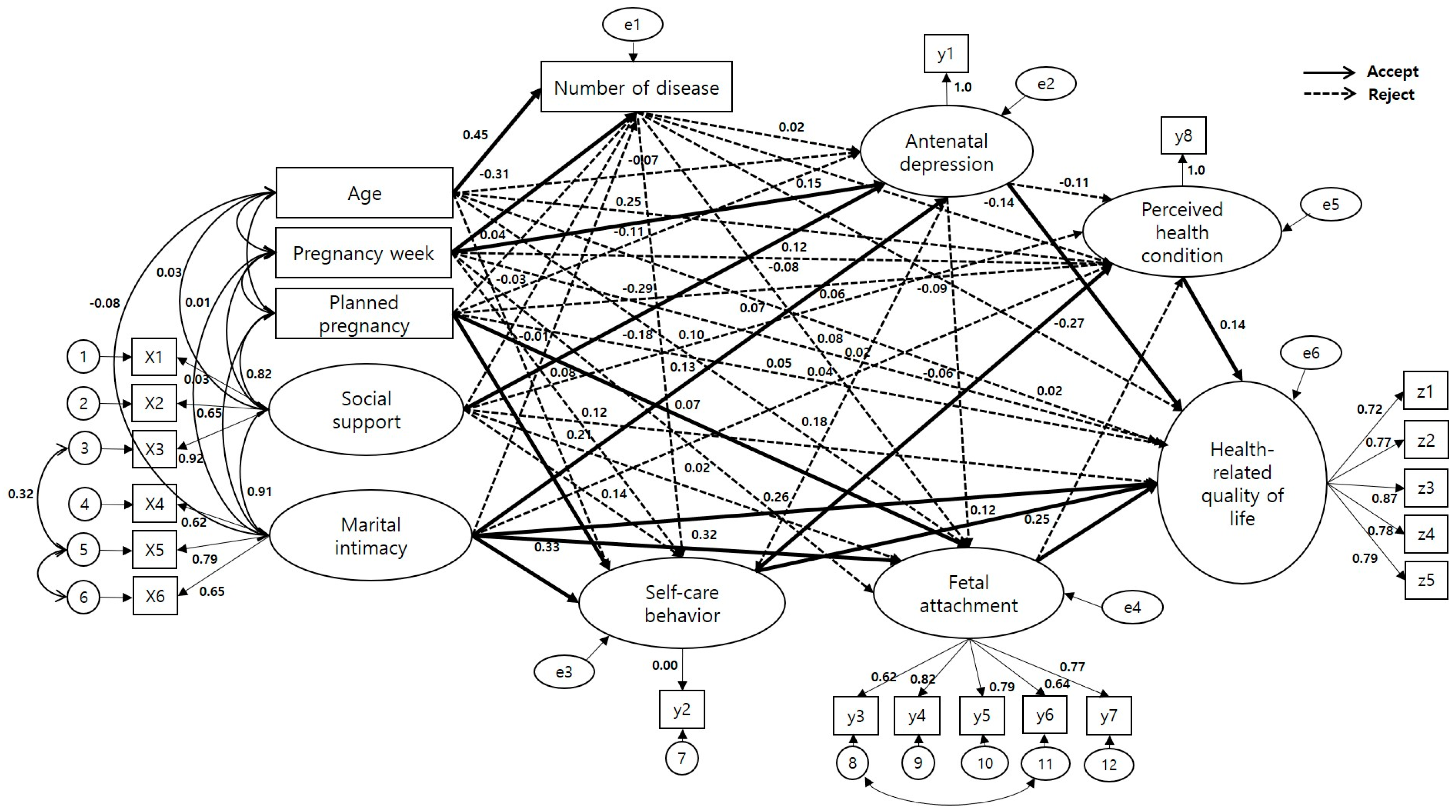

3.3.3. Path Estimates of the Modified Model

3.3.4. Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects of the Modified Model

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Clinical and Academic Practice

- ⬤

- Early assessment of resilience and perceived health status may help identify high-risk pregnant women at greater risk for diminished HRQoL during hospitalization.

- ⬤

- Targeted nursing interventions to enhance individual resilience and perceived family support should be incorporated into maternal care in the MFICU.

- ⬤

- Educational programs for nurses should emphasize psychological and relational aspects of care for high-risk pregnant women.

- ⬤

- Routine use of HRQoL-focused assessment tools can support individualized and patient-centered care planning.

- ⬤

- Research and curricula in academic nursing should integrate the multifactorial nature of HRQoL and structural modeling approaches to improve evidence-based practice.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life |

| MFICU | Maternal-fetal intensive care unit |

References

- Statistics Korea. Population Projection for Korea; Statistics Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301020300&bid=204&act=view&list_no=426806 (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Hwang, J.Y. Reclassification of high-risk pregnancy for maternal-fetal healthcare providers. J. Korean Soc. Matern. Child Health 2020, 24, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, W.; Wu, T.; Wu, S.; Wang, H.; Fawad, M.; Adane, A.A.; Dai, X.; Zhu, X.; Xu, X. Pregnancy with Multiple High-Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 04027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokou, R.; Lianou, A.; Lampridou, M.; Panagiotounakou, P.; Kafalidis, G.; Paliatsiou, S.; Volaki, P.; Tsantes, A.G.; Boutsikou, T.; Iliodromiti, Z.; et al. Neonates at Risk: Understanding the Impact of High-Risk Pregnancies on Neonatal Health. Medicina 2025, 61, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Raat, H.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Mautner, E.; Korfage, I.J. Trajectories and predictors of women’s health-related quality of life during pregnancy: A large longitudinal cohort study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrans, C.E.; Zerwic, J.J.; Wilbur, J.E.; Larson, J.L. Conceptual model of health-related quality of life. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2005, 37, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J. A Structural Equation Model of Health-Related Quality of Life in Postmenopausal Women with Metabolic Syndrome. Ph.D. Dissertation, Inje University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.K. Structural Equation Model of Health-Related Quality of Life in Female Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ph.D. Dissertation, Inje University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, I.B.; Cleary, P.D. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995, 273, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016 Classification of High-Risk Pregnancy; Korean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, E.H. A Structural Model for Health-Related Quality of Life in Middle Aged Women. Ph.D. Dissertation, Gongju University, Chungnam, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J.P. Concept and Understanding of Structural Equation Models; Hannarae: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017; pp. 1–568. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 2008, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.S.; Lee, Y.B. The effects of social supports on psychosocial well-being of the unemployed. Korean J. Soc. Welf. Stud. 1999, 37, 241–269. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.H. A measure of marital intimacy. J. Korean Home Manag. Assoc. 1995, 33, 235–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.W.; Kim, M.J.; Park, J.M. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; Korean Version: Reliability and Validity. Korean J. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 10, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.; McKenzie-McHarg, K.; Shakespeare, J.; Price, J.; Gray, R. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2009, 119, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.R. A Study on Gravida’s Health Belief Model and Antenatal Care. Master’s Thesis, Ewha Woman’s University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H. The Effect of Visual and Verbal Information by Antenatal Ultrasound on Maternal-Fetal Attachment and Self-Care. Master’s Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Speak, D.L.; Cowart, M.E.; Palet, K. Health perceptions and lifestyles of the elderly. Res. Nurs. Health 1989, 12, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whang, M.H. Structural Model for Self-Care and Well-Being of the Elderly. Ph.D. Dissertation, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cranley, M.S. Development of a tool for the measurement of maternal attachment during pregnancy. Nurs. Res. 1981, 30, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.Y. Effects on Maternal-Infant Attachment by the Taegyo-Perspective Prenatal Class. Master’s Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Min, S.K.; Lee, C.I.; Kim, K.I.; Suh, S.Y.; Kim, D.K. Development of Korean version of WHO Quality of Life Scale abbreviated version (WHOQOL-BREF). J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2000, 39, 571–579. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H.K.; Kim, K.H.; Yeoum, S.G.; Song, M.S.; Ahn, O.H.; Lee, J.W. Family support, intention of pregnancy and antenatal self-care of pregnant women. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2013, 9, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. Effects of Social Support, Pregnancy Stress, and Anxiety on Health-Related Quality of Life in Pregnant Women. Master’s Thesis, Suncheon National University, Suncheon, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, K.S. Prediction Model of Health-Related Quality of Life for Hospitalized Patient with Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Ph.D. Dissertation, Mokpo University, Mokpo, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, J.H. Influence of Pregnancy Stress, Maternal-Fetal Attachment, and Social Support on Prenatal Depression in High-Risk Pregnant Women. Master’s Thesis, Keimyung University, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2021; p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Han, R.R.; Sun, K.; Zheng, J.; Gao, L.L. Perceived stress, marital satisfaction, and prenatal depression among couples with gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2022, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.E. Impact of Sexual Attitude and Marital Intimacy on Sexual Satisfaction in Pregnant Couples: An Application of the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. Master’s Thesis, Dong-A University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2017; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.M.; Oh, E.J.; Sung, H.C.; Kim, M.J. Effects of a spouse’s aromatherapy hand massage on fatigue, stress, and a couple’s relationship in pregnant women. J. Korean Soc. Matern. Child Health 2022, 26, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedaso, A.; Adams, J.; Peng, W.; Sibbritt, D. The Relationship between Social Support and Mental Health Problems during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themistoklis, D.; Ioannis, T.; Foteini, C.; Apostolos, M.; David, R.; Apostolos, A. Antenatal depression among women hospitalized due to threatened preterm labor in a high-risk pregnancy unit in Greece. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 31, 919–929. [Google Scholar]

- Dağlar, G.; Bilgiç, D.; Özkan, S.A. Factors affecting the quality of life among pregnant women during the third trimester of pregnancy. Çukurova Med. J. 2019, 44, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzal, S.; Ayed, A.; Zaben, K.J.; Abu Ejheisheh, M.; AlBashtawy, M.; Batran, A. The Relationship between Quality of Life and Social Support among Pregnant Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024, 10, 23779608241301225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J. Influences of Partner Psychological Violence, Social Support, and Prenatal Depression on Health-Related Quality of Life in Pregnant Women. Master’s Thesis, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Republic of Korea, 2017; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.K.; Choi, J.H.; Chung, M.R. The effects of personal characteristics, marital intimacy and family support of pregnant couples on parent-fetal attachment. Early Child Educ. Care 2017, 12, 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.E. A study on the relationship between the health behavior and health-related quality of life during pregnancy and postpartum. Korea Assoc. Health Technol. 2019, 7, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Masoumeh, R.; Mahboubeh, P.; Zeinab, G.H. Effect of self-care before and during pregnancy to prevention and control pre-eclampsia in high-risk women. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M.; Gill, G.K.; Steele, C. Women’s experiences of factors that facilitate or inhibit gestational diabetes self-management. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandinava, H.; Sehhatie, F.; Mohammad-Alizadeh, S.; Ghanbari, S.; Mirghafourvand, M. Effect of educational package on self-care behavior, quality of life, and blood glucose levels in pregnant women with gestational diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Iran Red Crescent Med. J. 2017, 19, e44317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seid, S.S.; Amendoeira, J.; Ferreira, M.R. Self-care and quality of life among adult patients with heart failure: Scoping review. SAGE Open Nurs. 2023, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheryl, A.A. Maternal-Fetal Attachment and Its Relationship to Quality of Life in Pregnant Women with Diabetes. Ph.D. Dissertation, Loyola University, Chicago, IL, USA, 2022; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Prick, B.W.; Bijlenga, D.; Jansen, A.G.; Boers, K.E.; Scherjon, S.A.; Koopmans, C.M.; Van Pampus, M.G.; Essink-Bot, M.L.; Van Rhenen, D.J.; Mol, B.W.; et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life in the postpartum period after obstetric complications. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2015, 185, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Categories | N (%) or M ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34.19 ± 4.20 | |

| 20~29 | 28 (14.0) | |

| 30~39 | 151 (75.5) | |

| 40~49 | 21 (10.5) | |

| Religion | Yes | 60 (30.0) |

| No | 140 (70.0) | |

| Occupation | Yes | 97 (48.5) |

| No | 103 (51.5) | |

| Education | ≤High school | 25 (12.5) |

| ≥College | 175 (87.5) | |

| Number of pregnancies | 1.16 ± 1.15 | |

| 0 | 69 (34.5) | |

| 1 | 61 (30.5) | |

| 2 | 50 (25.0) | |

| ≥3 | 20 (10.0) | |

| Number of births | 0.51 ± 0.73 | |

| 0 | 122 (61.0) | |

| 1 | 58 (29.0) | |

| ≥2 | 20 (13.0) | |

| Number of miscarriages | 0 | 127 (63.5) |

| 1 | 47 (23.5) | |

| 2 | 21 (10.5) | |

| ≥3 | 5 (2.5) | |

| Number of children | 0.44 ± 0.63 | |

| 0 | 125 (62.5) | |

| 1 | 63 (32.5) | |

| ≥2 | 10 (5.0) | |

| Monthly income | 543.45 ± 0.62 | |

| (10,000 KRW) | <300 | 23 (11.5) |

| 300~500 | 76 (38.0) | |

| 501~700 | 60 (30.0) | |

| >700 | 41 (20.5) | |

| Family type | Large family | 8 (4.0) |

| Nuclear family | 182 (91.0) | |

| Others | 10 (5.0) | |

| Planned pregnancy | Yes | 75 (37.5) |

| No | 125 (62.5) | |

| High-risk pregnancy | Over 35 years of age | 90 (45.0) |

| diagnosis | Gestational diabetes | 17 (8.5) |

| (multiple responses) | Cervical incompetency | 25 (12.5) |

| Placenta previa | 25 (12.5) | |

| Oligohydramnios | 8 (4.0) | |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 16 (8.0) | |

| Multiple pregnancy | 27 (13.5) | |

| Gestational hypertension | 14 (7.0) | |

| Premature rupture of membrane | 19 (9.5) | |

| Labor pain | 71 (35.5) | |

| Ultrasonic abnormality | 30 (15.0) | |

| Mother with a condition that can affect pregnancy | 52 (26.0) |

| Variables | M ± SD | Scale Range | Skewness | Kurtosis | Standardized Factor Loading | SE | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social support | Family support | 4.49 ± 0.56 | 1–5 | −1.27 | 1.59 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.78 | |

| Friends support | 3.95 ± 0.82 | 1–5 | −0.57 | −0.05 | 0.64 | 0.12 | |||

| Others support | 4.48 ± 0.58 | 1–5 | −1.13 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 0.08 | |||

| Marital intimacy | Cognitive | 3.86 ± 0.59 | 1–5 | −0.48 | 0.61 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.83 | |

| Emotional | 3.82 ± 0.65 | 1–5 | −0.44 | −0.36 | 0.85 | 0.08 | |||

| Sexual | 3.52 ± 0.65 | 1–5 | 0.00 | −0.22 | 0.72 | 0.08 | |||

| Fetal attachment | Fetal division | 4.11 ± 0.59 | 1–5 | −0.33 | −0.11 | 0.65 | 0.94 | 0.76 | |

| Interaction | 4.11 ± 0.62 | 1–5 | −0.58 | 0.10 | 0.82 | 0.13 | |||

| Intent estimation | 4.26 ± 0.59 | 1–5 | −0.71 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 0.12 | |||

| Role acquisition | 4.38 ± 0.63 | 1–5 | −1.22 | 1.45 | 0.69 | 0.13 | |||

| Self-provided | 3.74 ± 0.65 | 1–5 | −0.07 | −0.19 | 0.74 | 0.14 | |||

| Health-related quality of life | Overall | 3.45 ± 0.77 | 1–5 | −0.51 | 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.95 | 0.79 | |

| Physical | 3.37 ± 0.63 | 1–5 | −0.36 | 0.30 | 0.75 | 0.09 | |||

| Psychological | 3.60 ± 0.57 | 1–5 | −0.27 | −0.14 | 0.87 | 0.08 | |||

| Social | 3.58 ± 0.61 | 1–5 | −0.10 | −0.01 | 0.79 | 0.09 | |||

| Environmental | 3.67 ± 0.59 | 1–5 | −0.20 | −0.24 | 0.80 | 0.08 | |||

| Fit Index | (p) | df | /df | SRMR | RMSEA | TLI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | p > 0.05 | ≤3 | ≤0.05 | ≤0.08 | ≥0.9 | ≥0.9 | |

| Hypothetical model | 456.81 (<0.001) | 185 | 2.47 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.83 | 0.87 |

| Modified model | 395.70 (<0.001) | 185 | 2.20 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.86 | 0.90 |

| Endogenous Variables | Exogenous Variables | SC | SE | CR | p | SMC | Adoption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of diseases | ←Age | 0.44 | 0.05 | 7.32 | <0.001 | 0.27 | Accept |

| ←Pregnancy week | −0.31 | 0.03 | −5.13 | <0.001 | Accept | ||

| ←Planned pregnancy | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 0.539 | Reject | ||

| ←Social support | −0.02 | 0.12 | −0.29 | 0.770 | Reject | ||

| ←Marital intimacy | −0.00 | 0.16 | −0.07 | 0.939 | Reject | ||

| Antenatal depression | ←Age | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.99 | 0.318 | 0.26 | Reject |

| ←Pregnancy week | −0.25 | 0.02 | −3.81 | <0.001 | Accept | ||

| ←Planned pregnancy | −0.10 | 0.07 | −1.71 | 0.087 | Reject | ||

| ←Social support | −0.29 | 0.08 | −3.28 | 0.001 | Accept | ||

| ←Marital intimacy | −0.18 | 0.11 | −2.01 | 0.044 | Accept | ||

| ←Number of disease | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.759 | Reject | ||

| Self-care behavior | ←Age | 0.07 | 0.03 | 1.15 | 0.249 | 0.29 | Reject |

| ←Pregnancy week | 0.12 | 0.02 | 1.83 | 0.067 | Reject | ||

| ←Planned pregnancy | 0.20 | 0.05 | 3.34 | <0.001 | Accept | ||

| ←Social support | 0.13 | 0.06 | 1.54 | 0.123 | Reject | ||

| ←Marital intimacy | 0.33 | 0.08 | 3.58 | <0.001 | Accept | ||

| ←Number of disease | −0.09 | 0.03 | −1.36 | 0.173 | Reject | ||

| ←Antenatal depression | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.72 | 0.466 | Reject | ||

| Fetal attachment | ←Age | 0.12 | 0.04 | 1.78 | 0.074 | 0.39 | Reject |

| ←Pregnancy week | 0.07 | 0.02 | 1.01 | 0.312 | Reject | ||

| ←Planned pregnancy | 0.20 | 0.05 | 3.34 | <0.001 | Accept | ||

| ←Social support | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.810 | Reject | ||

| ←Marital intimacy | 0.32 | 0.12 | 3.12 | 0.002 | Accept | ||

| ←Number of disease | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.27 | 0.787 | Reject | ||

| ←Antenatal depression | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.77 | 0.437 | Reject | ||

| Perceived health condition | ←Age | 0.14 | 0.06 | 1.95 | 0.051 | 0.46 | Reject |

| ←Pregnancy week | 0.12 | 0.04 | 1.62 | 0.103 | Reject | ||

| ←Planned pregnancy | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.87 | 0.381 | Reject | ||

| ←Social support | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.74 | 0.455 | Reject | ||

| ←Marital intimacy | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.890 | Reject | ||

| ←Number of disease | −0.14 | 0.07 | −1.84 | 0.065 | Reject | ||

| ←Antenatal depression | −0.10 | 0.10 | −4.14 | 0.159 | Reject | ||

| ←Self -care behavior | 0.17 | 0.15 | 2.11 | 0.035 | Accept | ||

| ←Fetal attachment | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.811 | Reject | ||

| Health-related quality of life | ←Age | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.11 | 0.265 | 0.73 | Reject |

| ←Pregnancy week | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.328 | Reject | ||

| ←Planned pregnancy | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 0.391 | Reject | ||

| ←Social support | 0.12 | 0.06 | 1.90 | 0.057 | Reject | ||

| ←Marital intimacy | 0.26 | 0.10 | 3.30 | <0.001 | Accept | ||

| ←Number of disease | −0.09 | 0.03 | −1.75 | 0.080 | Reject | ||

| ←Antenatal depression | −0.27 | 0.05 | −4.84 | <0.001 | Accept | ||

| ←Self-care behavior | 0.12 | 0.08 | 2.09 | 0.037 | Accept | ||

| ←Fetal attachment | 0.25 | 0.07 | 3.63 | <0.001 | Accept | ||

| ←Perceived health condition | 0.14 | 0.03 | 2.79 | 0.005 | Accept |

| Endogenous Variables | Exogenous Variables | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (p) | β (p) | β (p) | ||

| Number of diseases | ←Age | 0.44 (<0.001) | 0.44 (<0.001) | |

| ←Pregnancy week | −0.31 (<0.001) | −0.31 (<0.001) | ||

| ←Planned pregnancy | 0.03 (0.539) | 0.03 (0.539) | ||

| ←Social support | −0.02 (0.770) | −0.02 (0.770) | ||

| ←Marital intimacy | −0.00 (0.939) | −0.00 (0.939) | ||

| Antenatal depression | ←Age | −0.07 (0.318) | 0.01 (0.748) | −0.06 (0.165) |

| ←Pregnancy week | −0.25 (<0.001) | −0.00 (0.730) | −0.26 (0.011) | |

| ←Planned pregnancy | −0.10 (0.087) | 0.00 (0.557) | −0.10 (0.089) | |

| ←Social support | −0.29 (0.001) | −0.00 (0.620) | −0.29 (0.010) | |

| ←Marital intimacy | −0.18 (0.044) | 0.00 (0.888) | −0.18 (0.103) | |

| ←Number of disease | 0.02 (0.759) | 0.02 (0.759) | ||

| Self-care behavior | ←Age | 0.07 (0.249) | −0.04 (0.220) | 0.03 (0.498) |

| ←Pregnancy week | 0.12 (0.067) | 0.04 (0.118) | 0.16 (0.011) | |

| ←Planned pregnancy | 0.20 (<0.001) | 0.00 (0.786) | 0.20 (0.013) | |

| ←Social support | 0.13 (0.123) | 0.01 (0.327) | 0.15 (0.177) | |

| ←Marital intimacy | 0.33 (<0.001) | 0.01 (0.437) | 0.34 (0.008) | |

| ←Number of disease | −0.09 (0.173) | −0.00 (0.559) | −0.09 (0.191) | |

| ←Antenatal depression | −0.05 (0.466) | −0.05 (0.466) | ||

| Fetal attachment | ←Age | 0.12 (0.074) | 0.00 (0.825) | 0.13 (0.087) |

| ←Pregnancy week | 0.07 (0.312) | 0.07 (0.042) | 0.14 (0.067) | |

| ←Planned pregnancy | 0.07 (0.005) | 0.07 (0.005) | ||

| ←Social support | 0.02 (0.810) | 0.07 (0.088) | 0.09 (0.538) | |

| ←Marital intimacy | 0.32 (0.002) | 0.12 (0.003) | 0.44 (0.007) | |

| ←Number of disease | −0.02 (0.787) | −0.03 (0.196) | −0.05 (0.191) | |

| ←Antenatal depression | −0.05 (0.437) | −0.01 (0.329) | −0.07 (0.395) | |

| Perceived health condition | ←Age | 0.14 (0.051) | −0.04 (0.179) | 0.10 (0.319) |

| ←Pregnancy week | 0.12 (0.103) | 0.10 (0.005) | 0.24 (0.011) | |

| ←Planned pregnancy | −0.06 (0.381) | 0.04 (0.055) | 0.11 (0.834) | |

| ←Social support | 0.07 (0.455) | 0.06 (0.072) | 0.27 (0.266) | |

| ←Marital intimacy | 0.01 (0.890) | 0.09 (0.096) | 0.10 (0.407) | |

| ←Number of disease | −0.14 (0.065) | −0.02 (0.145) | −0.14 (0.069) | |

| ←Antenatal depression | −0.10 (0.159) | −0.01 (0.323) | −0.11 (0.112) | |

| ←Self -care behavior | 0.17 (0.035) | 0.00 (0.780) | 0.18 (0.054) | |

| ←Fetal attachment | 0.02 (0.811) | 0.02 (0.811) | ||

| Health-related quality of life | ←Age | 0.05 (0.265) | 0.02 (0.585) | 0.08 (0.215) |

| ←Pregnancy week | 0.05 (0.328) | 0.19 (0.008) | 0.24 (0.021) | |

| ←Planned pregnancy | 0.04 (0.391) | 0.06 (0.010) | 0.11 (0.123) | |

| ←Social support | 0.12 (0.057) | 0.14 (0.017) | 0.27 (0.044) | |

| ←Marital intimacy | 0.26 (<0.001) | 0.22 (0.006) | 0.48 (0.005) | |

| ←Number of disease | −0.09 (0.080) | −0.05 (0.189) | −0.14 (0.022) | |

| ←Antenatal depression | −0.27 (<0.001) | −0.04 (0.148) | −0.31 (0.007) | |

| ←Self -care behavior | 0.12 (0.037) | 0.11 (0.007) | 0.23 (0.011) | |

| ←Fetal attachment | 0.25 (<0.001) | 0.00 (0.897) | 0.25 (0.012) | |

| ←Perceived health condition | 0.14 (0.005) | 0.14 (0.005) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seol, H.; Oh, J.; Im, M. Health-Related Quality of Life Among High-Risk Pregnant Women Hospitalized in a Maternal-Fetal Intensive Care Unit: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192534

Seol H, Oh J, Im M. Health-Related Quality of Life Among High-Risk Pregnant Women Hospitalized in a Maternal-Fetal Intensive Care Unit: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192534

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeol, Hyuna, Jina Oh, and Mihae Im. 2025. "Health-Related Quality of Life Among High-Risk Pregnant Women Hospitalized in a Maternal-Fetal Intensive Care Unit: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192534

APA StyleSeol, H., Oh, J., & Im, M. (2025). Health-Related Quality of Life Among High-Risk Pregnant Women Hospitalized in a Maternal-Fetal Intensive Care Unit: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Healthcare, 13(19), 2534. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192534

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)