Outcomes of Fenestrating vs. Reconstituting Laparoscopic Subtotal Cholecystectomy: A Single-Center Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elshaer, M.; Gravante, G.; Thomas, K.; Sorge, R.; Al-Hamali, S.; Ebdewi, H. Subtotal cholecystectomy for ‘Difficult gallbladders’: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2015, 150, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulen, F.; Tihan, D.; Duman, U.; Bayam, E.; Zaim, G. Laparoscopic partial cholecystectomy: A safe and effective alternative surgical technique in ‘difficult cholecystectomies’. Turkish J. Surg. 2016, 32, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savader, S.J.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Prescott, C.A.; Winick, A.B.; Venbrux, A.C.; Lund, G.B.; Mitchell, S.E.; Cameron, J.L.; Osterman, F.A., Jr. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy-related bile duct injuries: A health and financial disaster. Ann. Surg. 1997, 225, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFadyen, B.V.; Vecchio, R.; Ricardo, A.E.; Mathis, C.R. Bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: The United States experience. Surg. Endosc. 1998, 12, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flum, D.R.; Cheadle, A.; Prela, C.; Dellinger, E.P.; Chan, L. Bile Duct Injury during Cholecystectomy and Survival in Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA 2003, 290, 2168–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, M.P.; Feurer, I.D.; Moore, D.E.; Zaydfudim, V.; Pinson, C.W. The long-term effect of bile duct injuries on health-related quality of life: A meta-analysis. HPB 2013, 15, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N.; Dugan, A.; Davenport, D.; Daily, M.; Shah, M.; Berger, J.; Gedaly, R. Risk factors for increased resource utilization and critical care complications in patients undergoing hepaticojejunostomy for biliary injuries. HPB 2016, 18, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yildirim, A.C.; Zeren, S.; Ekici, M.F.; Yaylak, F.; Algin, M.C.; Arik, O. Comparison of Fenestrating and Reconstituting Subtotal Cholecystectomy Techniques in Difficult Cholecystectomy. Cureus 2022, 14, e22441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, R.M.; Morin, M. Open cholecystectomy: Its morbidity and mortality as a reference standard. Can. J. Surg. 1993, 36, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shingu, Y.; Komatsu, S.; Norimizu, S.; Taguchi, Y.; Sakamoto, E. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy for severe cholecystitis. Surg. Endosc. 2016, 30, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel, A.; Shtamler, B. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy. J. Laparoendosc. Surg. 1993, 3, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, J.; Sasaki, A.; Obuchi, T.; Baba, S.; Nitta, H.; Wakabayashi, G. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy for severe cholecystitis. Surg. Today 2009, 39, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, A.H.; Donkervoort, S.C.; Lameris, W.; de Vries, E.; Eijsbouts, Q.A.; Vrouenraets, B.C.; Busch, O.R.; Boermeester, M.A.; de Reuver, P.R. Short- and Long-Term Outcomes after a Reconstituting and Fenestrating Subtotal Cholecystectomy. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2017, 225, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, A.Y.; Chean, C.S.; Durkin, D.; Bhatt, A.; Athwal, T.S. Short and long term outcomes of laparoscopic fenestrating or reconstituting subtotal cholecystectomy versus laparoscopic total cholecystectomy in the management of acute cholecystitis. HPB 2022, 24, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodvall, B.; Overgaard, B. Cystic duct remnant after cholecystectomy: Incidence studied by cholegraphy in 500 cases, and significance in 103 reoperations. Ann. Surg. 1966, 163, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasberg, S.M.; Pucci, M.J.; Brunt, L.M.; Deziel, D.J. Subtotal Cholecystectomy-‘Fenestrating’ vs. ‘reconstituting’ Subtypes and the Prevention of Bile Duct Injury: Definition of the Optimal Procedure in Difficult Operative Conditions. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2016, 222, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henneman, D.; da Costa, D.W.; Vrouenraets, B.C.; van Wagensveld, B.A.; Lagarde, S.M. Laparoscopic partial cholecystectomy for the difficult gallbladder: A systematic review. Surg. Endosc. 2013, 27, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaishnav, D.; Patel, B. ‘Difficult Gallbladder’ Incidence and Management at Speciality Surgical Unit. HPB 2021, 23, S352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoe, M.; Hata, J.; Takada, T.; Strasberg, S.M.; Asbun, H.J.; Wakabayashi, G.; Kozaka, K.; Endo, I.; Deziel, D.J.; Miura, F.; et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: Diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 2018, 25, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

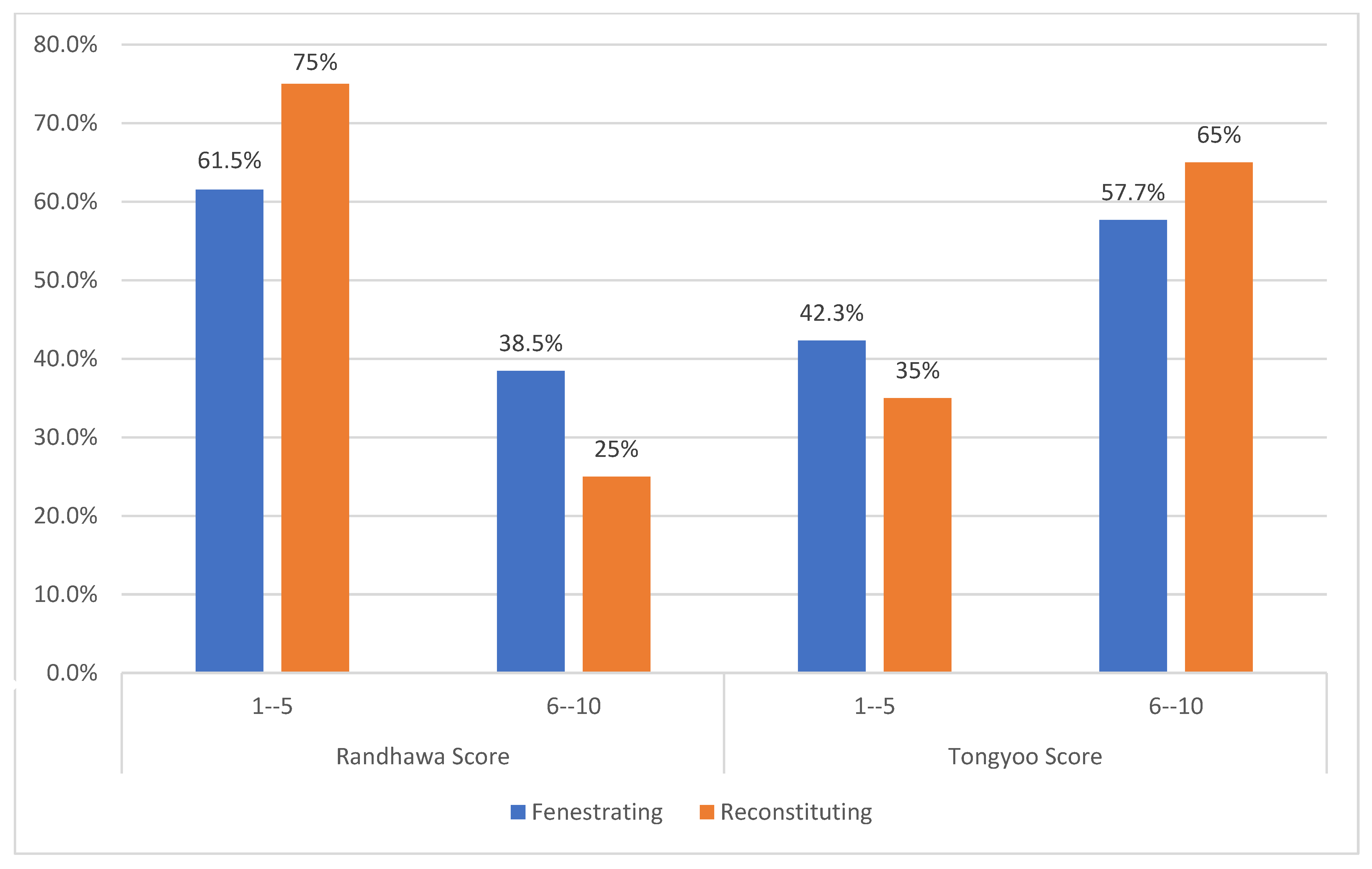

- Randhawa, J.S.; Pujahari, A.K. Preoperative prediction of difficult lap chole: A scoring method. Indian J. Surg. 2009, 71, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongyoo, A.; Liwattanakun, A.; Sriussadaporn, E.; Limpavitayaporn, P.; Mingmalairak, C. The Modification of a Preoperative Scoring System to Predict Difficult Elective Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2023, 33, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, S.R.; Moradi, D.; Samaan, B.M.; Chaudhry, U.S.; Nagpal, K.; Cosgrove, J.M.; Farkas, D.T. The degree of gallbladder wall thickness and its impact on outcomes after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 26, 3174–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Ranjan, G.; Arora, M.; Goswami, B.; Chaudhary, P.; Kapur, A.; Kumar, R.; Chand, T. Validation of a scoring system to predict difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int. J. Surg. 2013, 11, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.; Pathak, S.; Firdaus, H. Assessment of Operative Predictors for Difficulty in Laproscopic Cholecystectomy. Int. J. Contemp. Med. Res. 2016, 343, 2393–2915. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Azzawi, M.; Abouelazayem, M.; Parmar, C.; Singhal, R.; Amr, B.; Martinino, A.; Atıcı, S.D.; Mahawar, K. A systematic review on laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy for difficult gallbladders: A lifesaving bailout or an incomplete operation? Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2024, 106, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajibandeh, S.; Hajibandeh, S.; Parente, A.; Laing, R.W.; Bartlett, D.; Athwal, T.S.; Sutcliffe, R.P. Meta-analysis of fenestrating versus reconstituting subtotal cholecystectomy in the management of difficult gallbladder. HPB 2024, 26, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.; Wintrip, D.; Horgan, L.; Brown, J. Outcomes of laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy: A comparative analysis of fenestrating and reconstituting approaches in 170 cases. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 1484–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Briggs, E.; Tannouri, S.; Tatarian, T.; Pucci, M.J.; Tholey, R.M.; Chojnacki, K.A.; Foley, C.; Palazzo, F. What Happens After Discharge? A 2+ Year Follow-Up After Laparoscopic Subtotal Fenestrating and Reconstituting Cholecystectomy. Am. Surg. 2024, 90, 1800–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreuder, A.M.; Busch, O.R.; Besselink, M.G.; Ignatavicius, P.; Gulbinas, A.; Barauskas, G.; Gouma, D.J.; van Gulik, T.M. Long-Term Impact of Iatrogenic Bile Duct Injury. Dig. Surg. 2020, 37, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloraini, A.; Alanezi, T.; AlShahwan, N. Subtotal Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy versus Open Total Cholecystectomy for the Difficult Gallbladder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Curr. Probl. Surg. 2024, 61, 101607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloraini, A.; Alburakan, A.; Alhelal, F.S.; Alabdi, G.; Elmutawi, H.; Alzahrani, N.S.; Alkhalife, S.; Alanezi, T. Bailout for the Difficult Gallbladder: Subtotal vs. Open Cholecystectomy-A Retrospective Tertiary Care Center Experience. Medicina 2024, 60, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Grade | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Easy | Time taken: <60 min |

| No bile spillage | |

| No injury to the duct, artery | |

| Difficult | Time taken: 60–120 min |

| Bile/stone spillage | |

| Injury to the bile duct | |

| Very difficult | Time taken: >120 min |

| Fenestrating (n = 26) | Reconstituting (n = 20) | Total (n = 46) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) | 50.3 (17.9) | 46.4 (15.4) | 48.6 (16.8) | 0.393 |

| Sex | 0.474 | |||

| Female | 9 (34.6%) | 9 (45%) | 18 (39.1%) | |

| Male | 17 (65.4%) | 11 (55%) | 28 (60.9%) | |

| BMI, Mean (SD) | 30.8 (6.4) | 28.7 (6.5) | 29.9 (6.5) | 0.412 |

| Smoker Status | 0.043 | |||

| Ex-smoker | 1 (3.8%) | 0 | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Non-Smoker | 25 (96.2%) | 17 (85%) | 42 (91.3%) | |

| Smoker | 0 | 3 (15%) | 3 (6.5%) | |

| HTN | 7 (26.9%) | 7 (35%) | 14 (30.4%) | 0.75 |

| DM | 9 (34.6%) | 7 (35%) | 16 (34.8%) | 0.99 |

| DLP | 1 (3.8%) | 3 (15%) | 4 (8.7%) | 0.303 |

| CAD | 1 (3.8%) | 0 | 1 (2.2%) | 0.99 |

| Acute Pancreatitis | 1 (3.8%) | 0 | 1 (2.2%) | 0.99 |

| Liver Disease | 0 | 1 (5%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.44 |

| Renal Insufficiency | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (4.4%) | 0.99 |

| Other | 3 (11.5%) | 2 (10%) | 5 (10.8%) | 0.99 |

| Cholecystitis Type | 0.37 | |||

| Acute | 9 (34.6%) | 8 (40%) | 17 (37%) | |

| Acute on Chronic | 10 (38.5%) | 4 (20%) | 14 (30.4%) | |

| Chronic | 7 (26.9%) | 8 (40%) | 15 (32.6%) | |

| Operative Priority | 0.77 | |||

| Elective | 12 (46.2%) | 11 (55%) | 23 (50%) | |

| Emergency | 14 (53.8%) | 9 (45%) | 23 (50%) | |

| ASA Group | 0.621 | |||

| 1 or 2 | 22 (88%) | 19 (95%) | 41 (89.1%) | |

| 3 or 4 | 4 (12%) | 1 (5%) | 5 (10.8%) | |

| Tokyo Guidelines Grading | 0.027 | |||

| Grade 1 | 9 (34.6%) | 2 (10%) | 11 (23.9%) | |

| Grade 2 | 15 (57.7%) | 18 (90%) | 33 (71.7%) | |

| Grade 3 | 2 (7.7%) | 0 | 2 (4.3%) |

| Fenestrating (n = 26) | Reconstituting (n = 20) | Total (n = 46) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiologically contracted gallbladder? * | 10 (38.5%) | 6 (30%) | 16 (34.7%) | 0.796 |

| Irregular gallbladder wall? * | 2 (7.7%) | 0 | 2 (4.4%) | 0.045 |

| Clinically palpable gallbladder? | 0 | 1 (5%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.246 |

| Gallbladder Wall Thickness (mm) Classification ** | ||||

| N-Miss | 0 | 1 (5%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.292 |

| Normal | 2 (7.7%) | 4 (20%) | 6 (13%) | |

| Mild | 13 (50%) | 8 (40%) | 21 (45.6%) | |

| Moderate | 3 (11.5%) | 3 (15%) | 6 (13%) | |

| Severe | 8 (30.8%) | 4 (20%) | 12 (26.1%) | |

| Laboratory *** | ||||

| Total Bilirubin, Mean (SD) | 12.2 (9.7) | 12.7 (9.4) | 12.4 (9.4) | 0.931 |

| Direct Bilirubin, Mean (SD) | 8.7 (18.9) | 8.5 (14.1) | 8.6 (16.9) | 0.682 |

| ALP, Mean (SD) | 149.2 (150.8) | 187.3 (161.5) | 165.2 (154.7) | 0.267 |

| GGT, Mean (SD) | 125.9 (167.5) | 467.9 (1239.5) | 269.1 (816.7) | 0.431 |

| WBC count, Mean (SD) | 10.3 (4.8) | 12.6 (8.7) | 11.3 (6.7) | 0.659 |

| Albumin level, Mean (SD) | 33.8 (7.9) | 29.8 (11.8) | 32.1 (9.8) | 0.438 |

| Platelet count, Mean (SD) | 298.2 (95.7) | 265.5 (130.7) | 284.9 (110.9) | 0.159 |

| INR, Mean (SD) | 1.5 (2.5) | 1.1 (0.11) | 1.4 (1.9) | 0.586 |

| Fenestrating (n = 26) | Reconstituting (n = 20) | Total (n = 46) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative Difficulty | 0.784 | |||

| Difficult | 6 (23.1%) | 4 (20%) | 10 (21.7%) | |

| Very Difficult | 20 (76.9%) | 16 (80%) | 36 (78.3%) | |

| Operative Duration (min), Mean (SD) | 181.7 (64.2) | 191.8 (73.5) | 186.1 (67.7) | 0.65 |

| Blood Loss (mL), Mean (SD) | 153.9 (104.1) | 121.7 (105.7) | 139.1 (104) | 0.347 |

| BDI | 2 (7.7%) | 0 | 2 (4.3%) | 0.21 |

| Intraoperative Drain Placement | 23 (88.5%) | 15 (75%) | 38 (82.6%) | 0.232 |

| Peri-cholecystic Fluid Collection | 6 (23.1%) | 8 (40%) | 14 (30.4%) | 0.216 |

| Presence of Bile Leak | 6 (23.1%) | 2 (10%) | 8 (17.4%) | 0.246 |

| Previous History of Biliary Inflammation (Cholecystitis, Cholangitis) | 7 (26.9%) | 8 (40%) | 15 (32.6%) | 0.348 |

| Hospital Stay (days), Mean (SD) | 9 (3.3) | 5 (4.6) | 7.3 (4.4) | 0.977 |

| Follow-Up (months), Mean (SD) | 58.3 (86) | 31.2 (28.4) | 46.5 (68.1) | 0.144 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aloraini, A.; Alanezi, T.; Madkhali, A. Outcomes of Fenestrating vs. Reconstituting Laparoscopic Subtotal Cholecystectomy: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192465

Aloraini A, Alanezi T, Madkhali A. Outcomes of Fenestrating vs. Reconstituting Laparoscopic Subtotal Cholecystectomy: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192465

Chicago/Turabian StyleAloraini, Abdullah, Tariq Alanezi, and Ahmad Madkhali. 2025. "Outcomes of Fenestrating vs. Reconstituting Laparoscopic Subtotal Cholecystectomy: A Single-Center Retrospective Study" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192465

APA StyleAloraini, A., Alanezi, T., & Madkhali, A. (2025). Outcomes of Fenestrating vs. Reconstituting Laparoscopic Subtotal Cholecystectomy: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Healthcare, 13(19), 2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192465