Attitudes of Elderly Population Toward Mobile Health Applications in Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting

2.3. Population

2.4. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

2.5. Mobile Applications

2.6. Eligibility Criteria

2.7. Data Collection Tool and Variables

Application of H-TAM Framework

2.8. Scientific Rigor

2.9. Data Analysis

- Low: mean score < 3.0

- Good: mean score 3.0–3.9

- High: mean score ≥ 4.0.

2.10. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Anthropometric Measurements

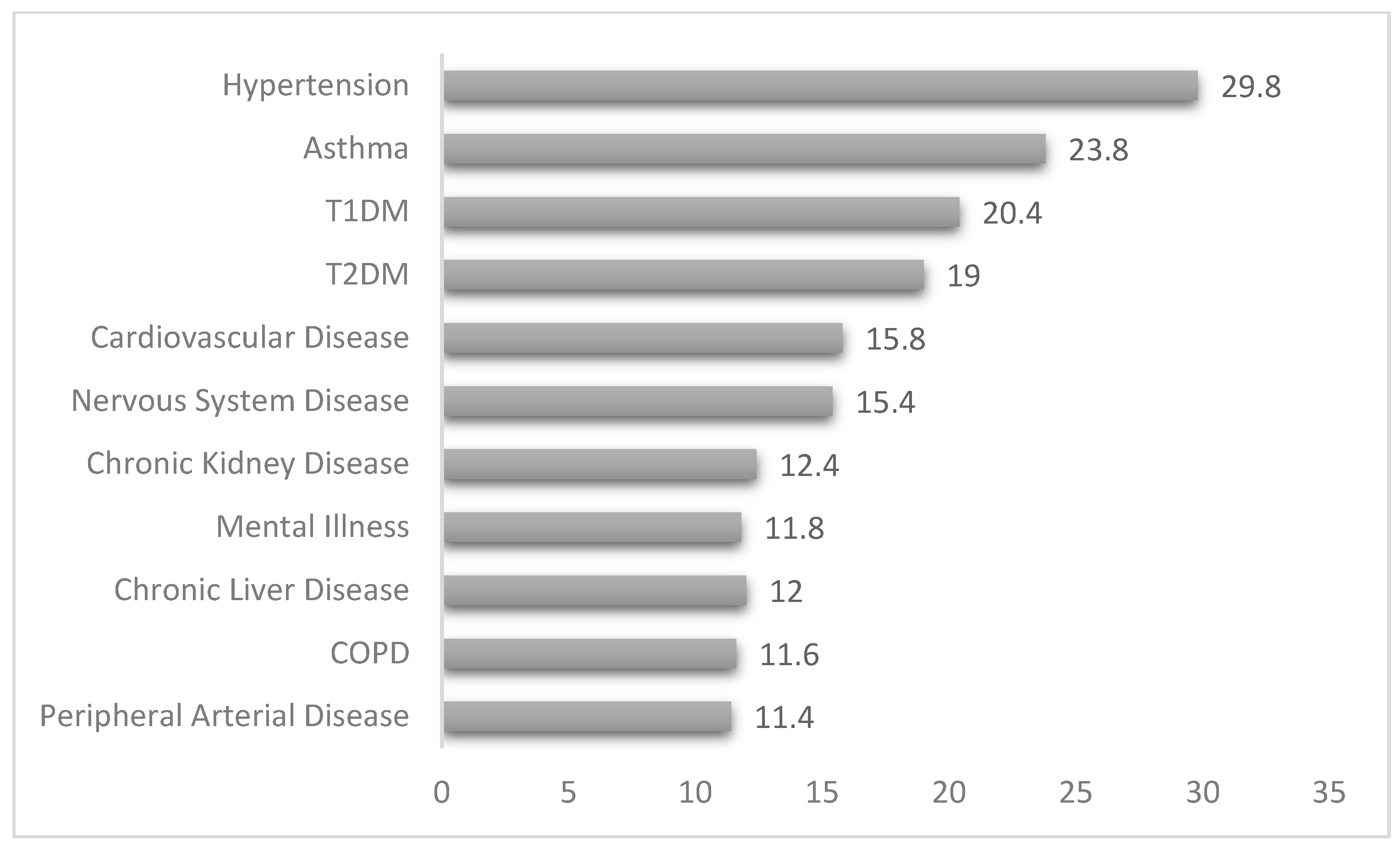

3.3. Comorbidity Status

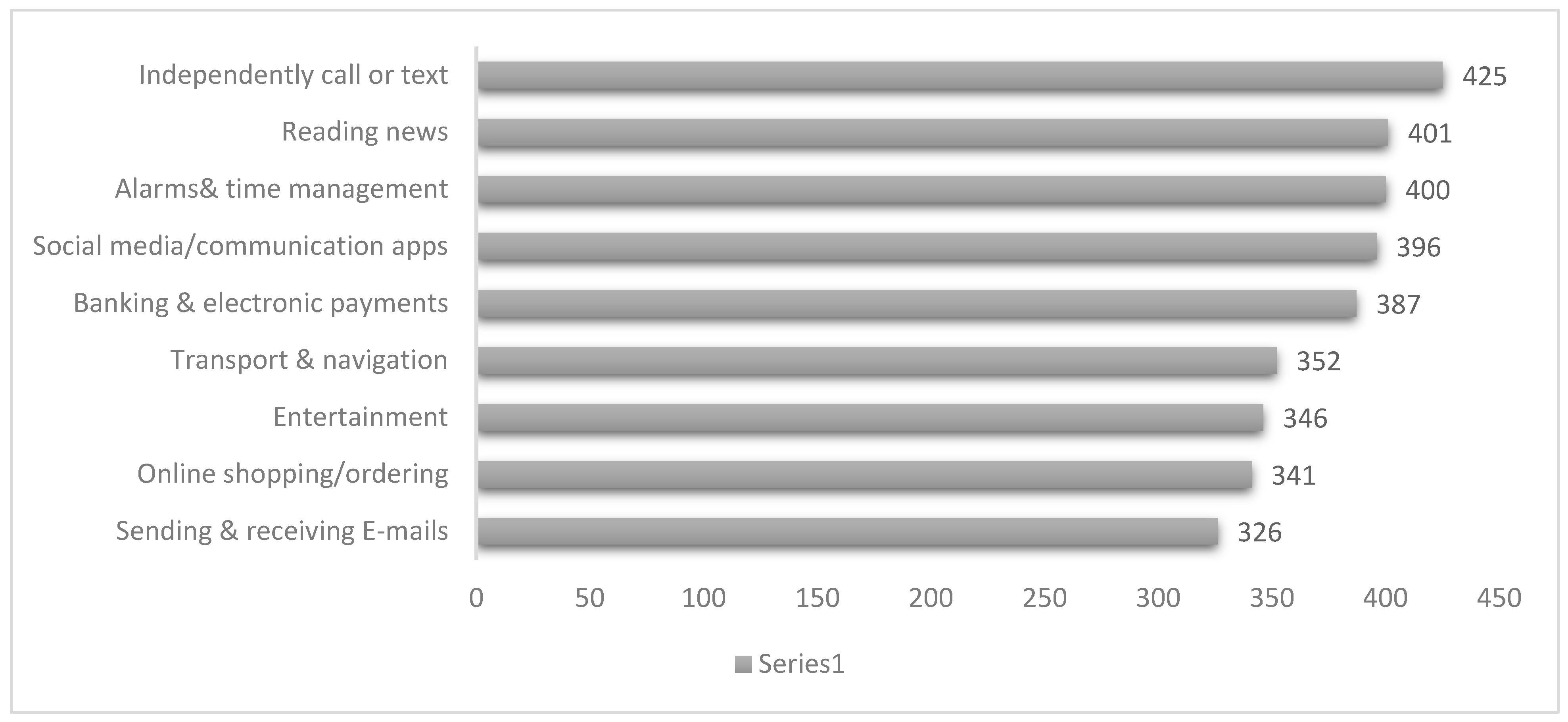

3.4. Usual Use of Mobile/Smart Phone

3.5. Awareness of Mobile Health Uses

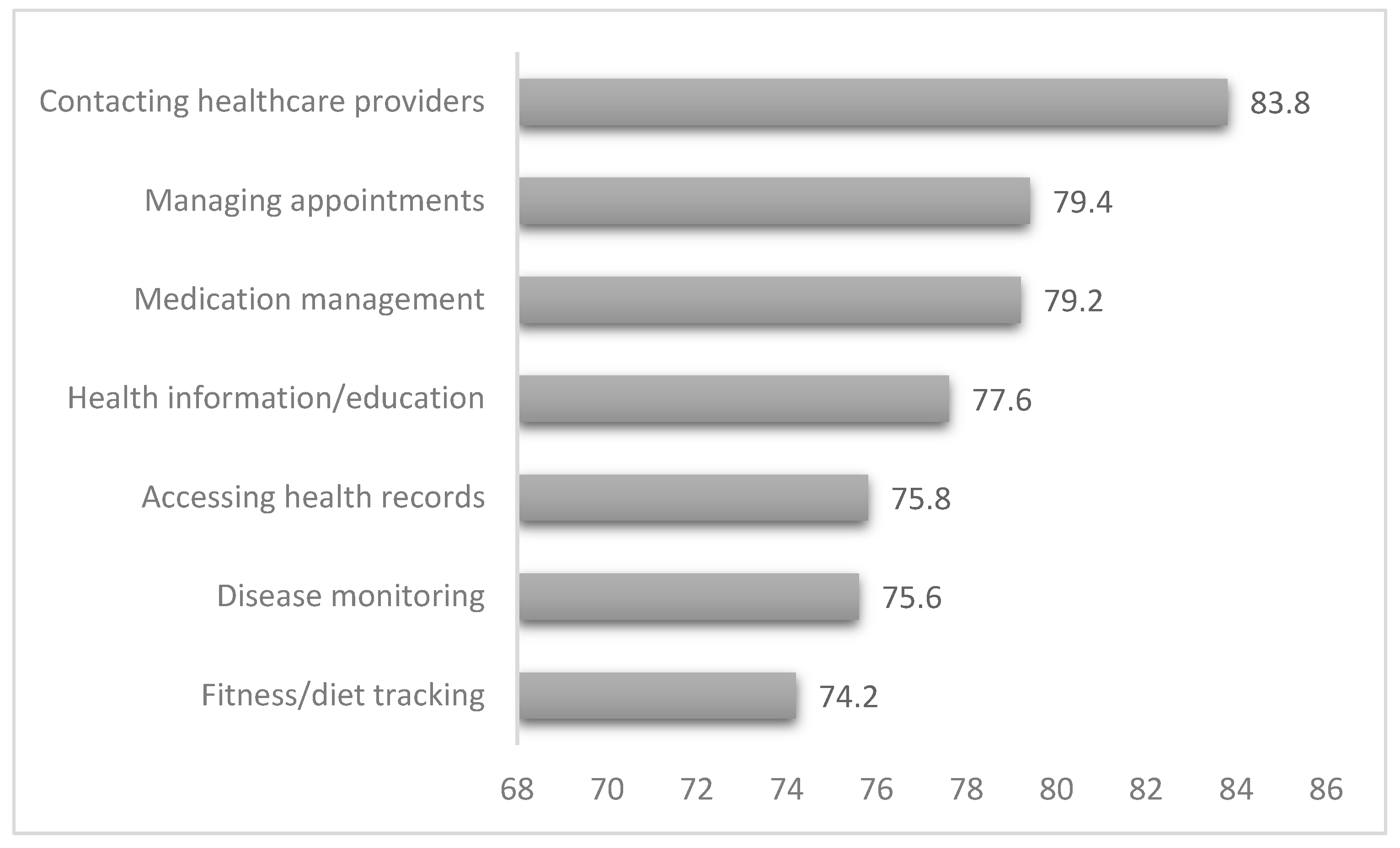

3.6. Actual Use of Mobile Health

3.7. Perceived Usefulness of Mobile Health

3.8. Attitude Toward Mobile Health

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harris, M.T.; Rogers, W.A. Developing a Healthcare Technology Acceptance Model (H-TAM) for older adults with hypertension. Ageing Soc. 2023, 43, 814–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Liu, C.; Gao, Q.S.; Yang, L.; Huang, X.; Guo, Q. Use of appropriate healthcare technologies: A cross-sectional study in rural Zhejiang of China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaghaslah, D.; Alsayari, A.; Almanasef, M.; Asiri, A. A Cross-Sectional Study on Pharmacy Students’ Career Choices in the Light of Saudi Vision 2030: Will Community Pharmacy Continue to Be the Most Promising, but Least Preferred, Sector? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaghaslah, D.; Alsayari, A.; Almaghaslah, S.; Alsanna, H. Patients’ Satisfaction with E-Prescribing [Wasfaty] in Saudi Arabia: A Survey of Country-Level Implementation. Healthcare 2022, 10, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcin, J.P.; Trujano, J.; Sadorra, C.; Dharmar, M. Telemedicine in Rural Pediatric Care: The Fundamentals. Pediatr. Ann. 2009, 38, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanzi, T. A Review of Mobile Applications Available in the App and Google Play Stores Used During the COVID-19 Outbreak. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Biswas, B. Doctor Consultation through Mobile Applications in India: An Overview, Challenges and the Way Forward. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2020, 26, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadi, A. Mobile Health Services in Saudi Arabia—Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraya, A.M.; Khardali, A.; Ahmad, S.; Hoshaibari, A.Z.; Alameer, A.A.; Jaafari, R.Y.; Thaibah, H.A.; Alfarhan, M.; Syed, M.H. Telehealth perceptions and associated factors among older adults with chronic conditions in Saudi Arabia: A comparative study of users and non-users. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1542974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzghaibi, H. Barriers to the Utilization of mHealth Applications in Saudi Arabia: Insights from Patients with Chronic Diseases. Healthcare 2025, 13, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhem, J.A. Factors, Barriers, and Recommendations Related to Mobile Health Acceptance among the Elderly in Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, S.A.; Rampal, L.; Ibrahim, F.; Radhakrishnan, A.P.; Kadir Shahar, H.; Othman, N. Mobile phone reminders and peer counseling improve adherence and treatment outcomes of patients on ART in Malaysia: A randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakkar, J.; Kurup, R.; Laba, T.L.; Santo, K.; Thiagalingam, A.; Rodgers, A.; Woodward, M.; Redfern, J.; Chow, C.K. Mobile Telephone Text Messaging for Medication Adherence in Chronic Disease: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, L.; Seaton, P. The Effectiveness of Self-Management Mobile Phone and Tablet Apps in Long-term Condition Management: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawski, K.; Ghazinouri, R.; Krumme, A.; Lauffenburger, J.C.; Lu, Z.; Durfee, E.; Durfee, E.; Oley, L.; Lee, J.; Mohta, N. Association of a Smartphone Application With Medication Adherence and Blood Pressure Control: The MedISAFE-BP Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, S.A. mHealth Applications in Saudi Arabia: Current Features and Future Opportunities. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Alharthi, M. Impact of COVID-19 on the Quality of Life of Households in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghareeb, M.; Albesher, A.S.; Asif, A. Studying Users’ Perceptions of COVID-19 Mobile Applications in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbilgahy, A.A.; Alenezi, M.H.; Alruwaili, A.H.; Alhathal, S.M. Role of mobile health applications in prevention and detection of pandemic disease: A population perspective. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241292106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, I.; Lim, Z.Z.; Ng, J.J.L.; Koh, W.J.; Wong, P.S. Public attitudes towards mobile health in Singapore: A cross-sectional study. mHealth 2018, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Guo, X.; Peng, Z.; Ye, Q.; Lai, K.H. Trust and elderly users’ continuance intention regarding mobile health services: The contingent role of health and technology anxieties. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 35, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, E.; Mashamba-Thompson, T.P. Mobile health applications for disease screening and treatment support in low- and middle-income countries: A narrative review. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevanynejad, S.; Niakan Kalhori, S.R.; Katigari, M.R.; Eshpala, R.H. Personalized Mobile Health for Elderly Home Care: A Systematic Review of Benefits and Challenges. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2023, 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J. Exploring digital health care: eHealth, mHealth, and librarian opportunities. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. JMLA 2021, 109, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eines, T.F.; Vatne, S. Nurses and nurse assistants’ experiences with using a design thinking approach to innovation in a nursing home. J. Nurs. Manag. 2018, 26, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, L.A.; Mulvaney, S.A.; Gebretsadik, T.; Ho, Y.-X.; Johnson, K.B.; Osborn, C.Y. Disparities in the use of a mHealth medication adherence promotion intervention for low-income adults with type 2 diabetes. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, K.J.; Yu, M.; Riley, W.T.; Patel, V.; Hughes, P.; Marchesini, K.; Atienza, A.A. Willingness to Exchange Health Information via Mobile Devices: Findings From a Population-Based Survey. Ann. Fam. Med. 2016, 14, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, G.; Tan, N.C.; Malhotra, R.; Padmanabhan, U.; Barbier, S.; Allen, J.C.; Østbye, T. Short-term trajectories of use of a caloric-monitoring mobile phone app among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a primary care setting. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, C.; Burkett, N.S.; Ovbiagele, B.; Mueller, M.; Patel, S.; Brunner-Jackson, B.; Saulson, R.; Treiber, F. Stroke patients and their attitudes toward mHealth monitoring to support blood pressure control and medication adherence. mHealth 2016, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessel, K.A.; Vogel, M.M.; Kessel, C.; Bier, H.; Biedermann, T.; Friess, H.; Herschbach, P.; von Eisenhart-Rothe, R.; Meyer, B.; Kiechle, M.; et al. Mobile Health in Oncology: A Patient Survey About App-Assisted Cancer Care. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017, 5, e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammar, T.; Nilsson, A.L.; Hovstadius, B. Patients’ views on electronic patient information leaflets. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 14, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari, F.; Navabi, N.; Gannat Alipoor, Z. Older adults’ attitudes and barriers toward the use of mobile phones. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayer, L.; Heldenbrand, S.; Anderson, P.; Gubbins, P.O.; Martin, B.C. Smartphone medication adherence apps: Potential benefits to patients and providers. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2013, 53, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santo, K.; Chow, C.K.; Thiagalingam, A.; Rogers, K.; Chalmers, J.; Redfern, J. MEDication reminder APPs to improve medication adherence in Coronary Heart Disease (MedApp-CHD) Study: A randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 269 | 53.8 |

| Female | 231 | 46.2 | |

| Age group | 60–69 years | 360 | 72 |

| 70–79 years | 84 | 16.8 | |

| 80–89 years | 47 | 9.4 | |

| 90–99 years | 9 | 1.8 | |

| Marital status | Single | 50 | 10 |

| Married | 318 | 63.6 | |

| Divorced | 44 | 8.8 | |

| Widow | 88 | 17.6 | |

| Education | Illiterate | 132 | 26.4 |

| School | 222 | 44.4 | |

| University | 146 | 29.2 | |

| Income | Weak < 5000 SAR/month | 73 | 14.6 |

| Good 5000–10,000 SAR/month | 321 | 64.2 | |

| High > 10,000 SAR/month | 106 | 21.2 | |

| Previous employment | None | 168 | 33.6 |

| Governmental | 175 | 35 | |

| Private | 64 | 12.8 | |

| Personal/freelancer | 76 | 15.2 | |

| Others | 17 | 3.4 | |

| Living alone | Yes | 120 | 24 |

| No | 380 | 76 | |

| Smoking Status | Non-smoker | 387 | 77.4 |

| Ex-smoker | 74 | 14.8 | |

| Current smoker | 39 | 7.8 | |

| Characteristic | Awareness Level | df | X2 | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aware | Not Aware | |||||

| Gender | Male | 187 | 82 | 1 | 0.218 | 0.357 |

| Female | 165 | 66 | ||||

| Age group | 60–69 years | 266 | 94 | 3 | 11.748 | 0.008 |

| 70–79 years | 55 | 29 | ||||

| 80–89 years | 24 | 23 | ||||

| 90–99 years | 7 | 2 | ||||

| Marital status | Single | 32 | 18 | 3 | 6.954 | 0.073 |

| Married | 235 | 83 | ||||

| Divorced | 25 | 19 | ||||

| Widow | 60 | 28 | ||||

| Education | Illiterate | 88 | 44 | 2 | 1.203 | 0.548 |

| School | 159 | 63 | ||||

| University | 105 | 41 | ||||

| Income | Weak | 41 | 32 | 2 | 8.400 | 0.015 |

| Good | 235 | 86 | ||||

| High | 76 | 30 | ||||

| Previous employment | None | 121 | 47 | 4 | 7.284 | 0.121 |

| Governmental | 125 | 50 | ||||

| Private | 45 | 19 | ||||

| Personal/freelancer | 54 | 22 | ||||

| Others | 7 | 10 | ||||

| Living alone | Yes | 66 | 54 | 1 | 17.970 | <0.001 |

| No | 286 | 94 | ||||

| Smoking Status | Non-smoker | 288 | 99 | 2 | 14.863 | 0.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 39 | 35 | ||||

| Current smoker | 25 | 14 | ||||

| Item | Response [Frequency] | Skewness | Mean | SD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| Managing appointments | 37 | 53 | 42 | 35 | 333 | −1.258 | 4.15 | 1.350 |

| Accessing health records | 27 | 46 | 62 | 44 | 321 | −1.251 | 4.17 | 1.262 |

| Health information/education | 33 | 22 | 55 | 53 | 337 | −1.578 | 4.28 | 1.216 |

| Fitness/diet tracking | 34 | 28 | 44 | 50 | 344 | −1.594 | 4.28 | 1.239 |

| Disease monitoring | 29 | 25 | 46 | 45 | 355 | −1.709 | 4.34 | 1.187 |

| Medication management | 34 | 27 | 41 | 42 | 356 | −1.669 | 4.32 | 1.234 |

| Contacting healthcare providers | 27 | 25 | 49 | 47 | 352 | −1.693 | 4.34 | 1.171 |

| Characteristic | Perceived Usefulness | df | X2 | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Good | High | |||||

| Gender | Male | 9 | 82 | 178 | 2 | 2.934 | 0.231 |

| Female | 7 | 55 | 169 | ||||

| Age group | 60–69 years | 11 | 83 | 266 | 6 | 22.914 | 0.001 |

| 70–79 years | 2 | 27 | 55 | ||||

| 80–89 years | 2 | 25 | 20 | ||||

| 90–99 years | 1 | 2 | 6 | ||||

| Marital status | Single | 2 | 13 | 35 | 6 | 29.040 | <0.001 |

| Married | 11 | 67 | 240 | ||||

| Divorced | 2 | 24 | 18 | ||||

| Widow | 1 | 33 | 54 | ||||

| Education | Illiterate | 6 | 35 | 91 | 4 | 4.154 | 0.386 |

| School | 5 | 55 | 162 | ||||

| University | 5 | 47 | 94 | ||||

| Income | Weak | 4 | 28 | 41 | 4 | 17.152 | 0.002 |

| Good | 11 | 70 | 240 | ||||

| High | 1 | 39 | 66 | ||||

| Previous employment | None | 4 | 41 | 123 | 8 | 5.649 | 0.686 |

| Governmental | 7 | 50 | 118 | ||||

| Private | 0 | 19 | 45 | ||||

| Personal/freelancer | 4 | 22 | 50 | ||||

| Others | 1 | 5 | 11 | ||||

| Living alone | Yes | 2 | 53 | 65 | 2 | 22.639 | <0.001 |

| No | 14 | 84 | 282 | ||||

| Smoking Status | Non-smoker | 12 | 88 | 287 | 4 | 20.186 | <0.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 3 | 30 | 41 | ||||

| Current smoker | 1 | 19 | 19 | ||||

| Item | Response [Frequency] | Skewness | Mean | SD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

| I think mobile health has the potential to make me healthier. | 38 | 42 | 46 | 50 | 324 | −1.319 | 4.16 | 1.318 |

| I am keen to learn about and try new mobile health solutions in future. | 21 | 36 | 69 | 55 | 319 | −1.336 | 4.23 | 1.18 |

| I would be willing to pay for mobile health solutions. | 37 | 20 | 70 | 55 | 318 | −1.404 | 4.19 | 1.252 |

| Characteristic | Attitude | df | X2 | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Neutral | Positive | |||||

| Gender | Male | 17 | 57 | 195 | 2 | 1.019 | 0.601 |

| Female | 10 | 48 | 173 | ||||

| Age group | 60–69 years | 16 | 65 | 279 | 6 | 28.736 | <0.001 |

| 70–79 years | 8 | 19 | 57 | ||||

| 80–89 years | 1 | 21 | 25 | ||||

| 90–99 years | 2 | 0 | 7 | ||||

| Marital status | Single | 2 | 9 | 39 | 6 | 6.083 | 0.414 |

| Married | 14 | 67 | 237 | ||||

| Divorced | 4 | 13 | 27 | ||||

| Widow | 7 | 16 | 65 | ||||

| Education | Illiterate | 9 | 24 | 99 | 4 | 5.250 | 0.263 |

| School | 13 | 42 | 167 | ||||

| University | 5 | 39 | 102 | ||||

| Income | Weak | 8 | 17 | 48 | 4 | 11.395 | 0.022 |

| Good | 18 | 60 | 243 | ||||

| High | 1 | 28 | 77 | ||||

| Previous employment | None | 9 | 26 | 133 | 8 | 10.533 | 0.230 |

| Governmental | 11 | 39 | 125 | ||||

| Private | 1 | 21 | 42 | ||||

| Personal/freelancer | 5 | 16 | 55 | ||||

| Others | 1 | 3 | 13 | ||||

| Living alone | Yes | 6 | 37 | 77 | 2 | 9.226 | 0.010 |

| No | 21 | 68 | 291 | ||||

| Smoking Status | Non-smoker | 20 | 68 | 299 | 4 | 13.319 | 0.010 |

| Ex-smoker | 5 | 23 | 46 | ||||

| Current smoker | 2 | 14 | 23 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alqahtani, N.; Almaghaslah, D. Attitudes of Elderly Population Toward Mobile Health Applications in Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192464

Alqahtani N, Almaghaslah D. Attitudes of Elderly Population Toward Mobile Health Applications in Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192464

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlqahtani, Nada, and Dalia Almaghaslah. 2025. "Attitudes of Elderly Population Toward Mobile Health Applications in Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192464

APA StyleAlqahtani, N., & Almaghaslah, D. (2025). Attitudes of Elderly Population Toward Mobile Health Applications in Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(19), 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192464