Using the Chinese Version of the Screen for Disordered Eating to Assess Disordered Eating: Reliability, Validity and Correlates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Difficulty Parameters

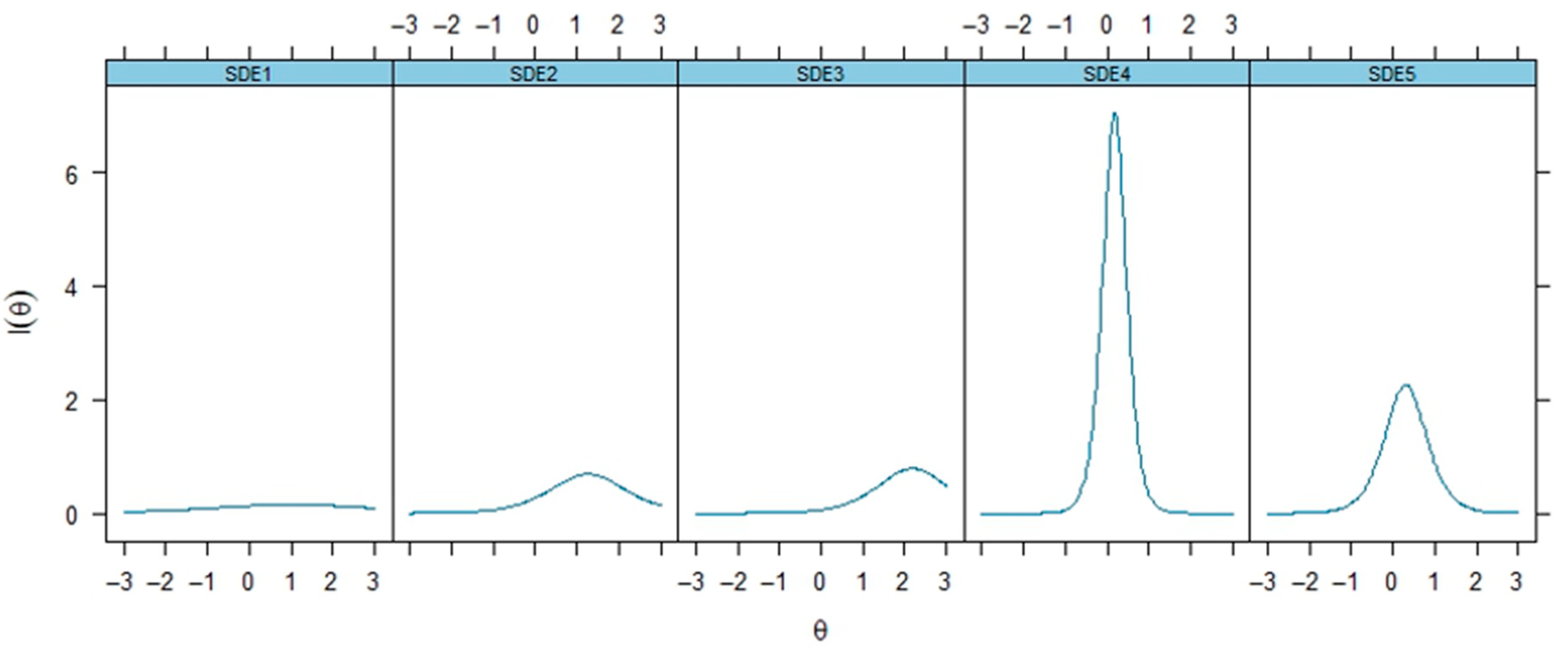

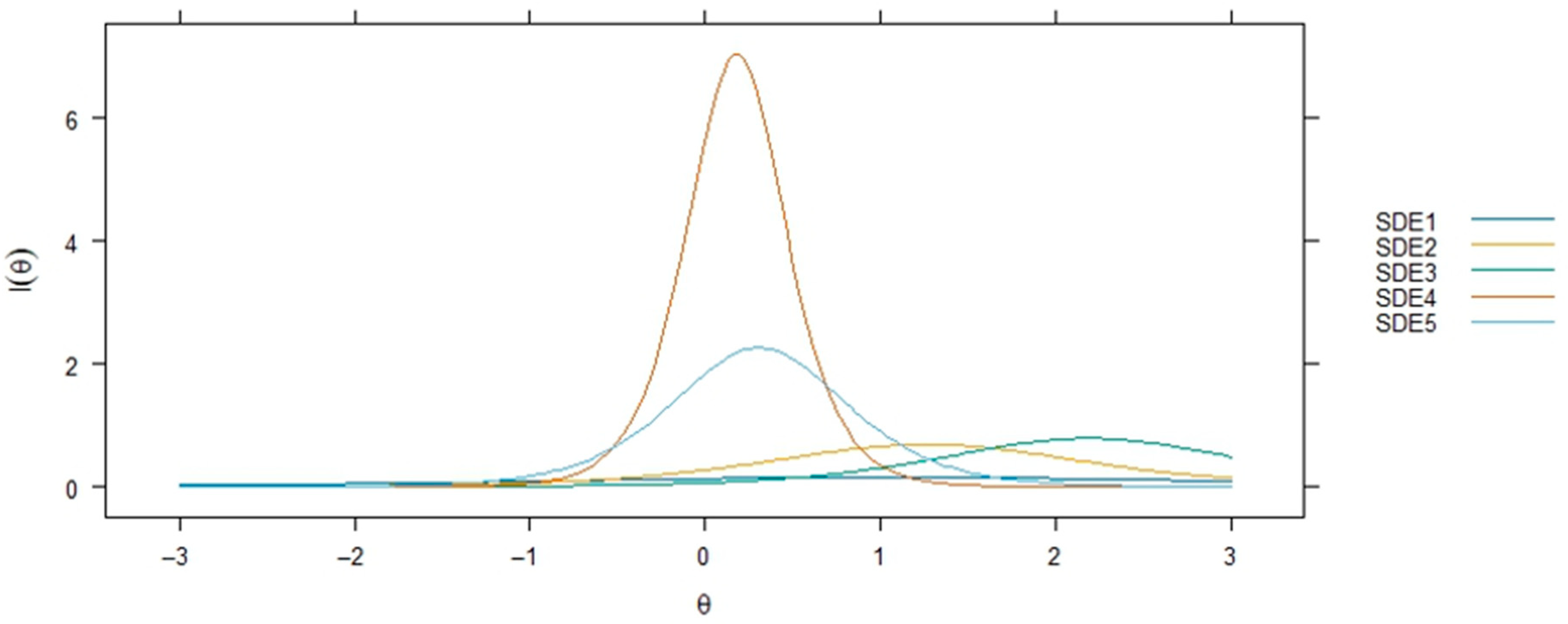

3.2. Discrimination Parameters

3.3. Item Fit Statistics

3.4. Sampling Adequacy and Internal Consistency

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDE | Screen for Disordered Eating |

| SCOFF | Sick, Control, One Fat, and Food |

| IRT | Item Response Theory |

| IIC | item information curves |

| ICC | item characteristic curves |

| RMSEA | root mean square error of approximation |

References

- Ralph, A.F.; Brennan, L.; Byrne, S.; Caldwell, B.; Farmer, J.; Hart, L.M.; Heruc, G.A.; Maguire, S.; Piya, M.K.; Quin, J.; et al. Management of eating disorders for people with higher weight: Clinical practice guideline. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Cooper, Z. Eating disorders, DSM–5 and clinical reality. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 198, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfalahi, M.; Mahadevan, S.; Balushi, R.A.; Chan, M.F.; Saadon, M.A.; Al-Adawi, S.; Qoronfleh, M.W. Prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating in Western Asia: A systematic review and meta-Analysis. Eat. Disord. 2022, 30, 556–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, P.; Aouad, P.; Le, A.; Marks, P.; Maloney, D.; Touyz, S.; Maguire, S. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Population, prevalence, disease burden and quality of life informing public policy in Australia-a rapid review. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhaj, O.A.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Sweidan, D.H.; Saif, Z.; Khudhair, M.F.; Ghazzawi, H.; Nadar, M.S.; Alhajeri, S.S.; Levine, M.P.; Jahrami, H. The prevalence and risk factors of screen-based disordered eating among university students: A global systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2022, 27, 3215–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreshe, E.; Paxton, S.; Miskovic-Wheatley, J.; Bryant, E.; Le, A.; Maloney, D.; Touyz, S.; Maguire, S. Prevention and early intervention in eating disorders: Findings from a rapid review. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokiniemi, K.; Pietila, A.M.; Mikkonen, S. Construct validity of clinical nurse specialist core competency scale: An exploratory factor analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, R.A.; Attia, E.; Fitzpatrick, J.J.; Phillips, K.; Nolan, S. Eating disorders: Identification and management in general medical and psychiatric settings. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2023, 29, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.F.; Reid, F.; Lacey, J.H. The SCOFF questionnaire: Assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ 1999, 319, 1467–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutz, A.M.; Marsh, A.G.; Gunderson, C.G.; Maguen, S.; Masheb, R.M. Eating Disorder Screening: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Characteristics of the SCOFF. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.F.; Lee, K.L.; Lee, S.M.; Leung, S.C.; Hung, W.S.; Lee, W.L.; Leung, Y.Y.; Li, M.W.; Tse, T.K.; Wong, H.K.; et al. Psychometric properties of the SCOFF questionnaire (Chinese version) for screening eating disorders in Hong Kong secondary school students: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguen, S.; Hebenstreit, C.; Li, Y.; Dinh, J.V.; Donalson, R.; Dalton, S.; Rubin, E.; Masheb, R. Screen for Disordered Eating: Improving the accuracy of eating disorder screening in primary care. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2018, 50, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solly, J.E.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Lust, K.; Grant, J.E. Binge-eating disorder in university students: High prevalence and strong link to impulsive and compulsive traits. CNS Spectr. 2023, 28, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.T.; Silva, A.; Brito, M.J.; Marques, C.; Araújo, A.; Macedo, A.; Renca, S. The Portuguese version of the screen for disordered eating: Validity and reliability in men across multiple ages. Eur. Psychiat. 2024, 67, S564. [Google Scholar]

- Dorflinger, L.M.; Ruser, C.B.; Masheb, R.M. A brief screening measure for binge eating in primary care. Eat. Behav. 2017, 26, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazzawi, H.A.; Nimer, L.S.; Haddad, A.J.; Alhaj, O.A.; Amawi, A.T.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Trabelsi, K.; Seeman, M.V.; Jahrami, H. A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of the prevalence of self-reported disordered eating and associated factors among athletes worldwide. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerasidou, A.; Horn, R. Making space for empathy: Supporting doctors in the emotional labour of clinical care. BMC Med. Ethics 2016, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elmore, N.; Burt, J.; Abel, G.; Maratos, F.A.; Montague, J.; Campbell, J.; Roland, M. Investigating the relationship between consultation length and patient experience: A cross-sectional study in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e896–e903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irving, G.; Neves, A.L.; Dambha-Miller, H.; Oishi, A.; Tagashira, H.; Verho, A.; Holden, J. International variations in primary care physician consultation time: A systematic review of 67 countries. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, M.A.; Ball, C.; Robinson, P. Four simple questions can help screen for eating disorders. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.; Fung, H.W.; Choi, T.M.; Ross, C.A. Using Online Methods to Develop and Examine the Hong Kong Chinese Translation of the Dissociative Experiences Scale. J. Evid. Inf. Soc. Work. 2017, 14, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, S.P.; Craig, C.S. Collaborative and iterative translation: An alternative approach to back translation. J. Int. Mark. 2007, 15, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, H.W.; Chan, C.; Lee, C.Y.; Ross, C.A. Using the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) checklist for DSM-5 to screen for PTSD in the Chinese context: A pilot study in a psychiatric sample. J. Evid.-Based Soc. Work 2019, 16, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravani, Y.; Dastjerdi, H.V. Back translation vs. collaborative translation: A comparative study of Persian subtitles in English movies. Leb. Sprachen 2013, 58, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Lopez, C.I.; Romero-Ibarguengoitia, M.E.; Cobos-Aguilar, H. Risk of positive screening for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and night eating syndrome and associated risk factors in medical fellows in Northeastern Mexico: A multicenter study. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, L.; Pasquarella, C.; Odone, A.; Colucci, M.E.; Costanza, A.; Serafini, G.; Aguglia, A.; Belvederi Murri, M.; Brakoulias, V.; Amore, M.; et al. Screening for depression in primary care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Bian, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Du, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, M. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2014, 36, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.M.; Benecke, C.; Kasinger, C.; Brahler, E.; Ehrenthal, J.C.; Strauss, B.; Ernst, M. Eating disorder psychopathology: The role of attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, and personality functioning. J. Psychosom. Res. 2022, 160, 110975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Li, Y.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Qian, X.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Dong, X.; et al. Adaptation of the two-item generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-2) to Chinese rural population: A validation study and meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R.; Freyd, J.J. Self-reports of potentially traumatic experiences in an adult community sample: Gender differences and test-retest stabilities of the items in a brief betrayal-trauma survey. J. Trauma Dissociation 2006, 7, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, H.W.; Chien, W.T.; Lam, S.K.K.; Ross, C.A. Prevalence and correlates of dissociative symptoms among people with depression. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 154, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Wedding, D.; Gwet, K.L. A comparison of Cohen’s Kappa and Gwet’s AC1 when calculating inter-rater reliability coefficients: A study conducted with personality disorder samples. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory 3E; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, Y. The Effect of Exercise Motivation on Eating Disorders in Bodybuilders in Social Networks: The Mediating Role of State Anxiety. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 7426601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, M.; Foster, T.; Messore, J.; Robinson, L.; Probst, Y. Food for the Mind: A systematic review of mindful and intuitive eating approaches for mental health & wellbeing. Eur. Psychiatry 2024, 67, S158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Conner, M.; Clancy, F.; Moss, R.; Wilding, S.; Bristow, M.; O’connor, D.B. Stress and eating behaviours in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2022, 16, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matlock, K.L.; Turner, R. Unidimensional IRT item parameter estimates across equivalent test forms with confounding specifications within dimensions. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2016, 76, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holmes, S.; Ma, H. A feminist approach to eating disorders in China: A qualitative study. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Chan, R.C.K.; Li, X.; Arcelus, J.; Yue, L.; Huang, J.; Gu, L.; Fan, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Psychometric Properties of the Chinese Version of the Eating Attitudes Test in Young Female Patients with Eating Disorders in Mainland China. Uropean Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc. 2017, 25, 613–617. [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez, J.P.; Archila-Godinez, J.C. Social and cultural influences on food choices: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 3698–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.S.; Liu, S.J.; Liu, M.M. Validation and Psychometric Properties of the Chinese Version of the Binge Eating Scale in Young Adults. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, C.; Yim, I.S. Internalized weight bias and eating disorder risk: The moderating role of self-construal among culturally diverse female young adults. Stigma Health 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazzawi, H.A.; Nimer, L.S.; Sweidan, D.H.; Alhaj, O.A.; Abulawi, D.; Amawi, A.T.; Levine, M.P.; Jahrami, H. The global prevalence of screen-based disordered eating and associated risk factors among high school students: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.C.; Gan, S.T.; Lee, C.T.; Liang, Y.L.; Lee, L.T.; Lin, S.H. National population-based data on the incidence, prevalence, and psychiatric comorbidity of eating disorders in Taiwanese adolescents and young adults. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschrich, R.L.; Halbeisen, G.; Steins-Loeber, S.; Timmesfeld, N.; Paslakis, G. Investigating the structure of disordered eating symptoms in adult men: A network analysis. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2025, 33, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, A.E.; Cordell, K.; Snowden, L.R.; Accurso, E.C. Characterizing Medical Complications in Publicly Insured Youth With Eating Disorders. J. Adolesc. Health 2024, 74, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doley, J.R.; Hart, L.M.; Stukas, A.A.; Petrovic, K.; Bouguettaya, A.; Paxton, S.J. Interventions to reduce the stigma of eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, S.; Xu, H.; Peng, J.; Wang, P.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Shi, X.; Zhang, W.; Shi, L.; et al. The burden of mental disorders in Asian countries, 1990–2019: An analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tu, W.; Yin, T.; Mei, Z.; Zhang, S.; Gu, W.; Liu, H.; Xu, G. ‘Food doesn’t control me anymore!’ psychosocial experiences during dietary management in adults with inflammatory bowel disease: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 4077–4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Size | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 436 | 56.9 |

| Male | 327 | 42.7 |

| Educational level | ||

| Associate degree or equivalent level | 240 | 31.3 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 516 | 67.4 |

| Master’s degree and above | 10 | 1.3 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 3 | 0.4 |

| Single | 762 | 99.5 |

| Divorced | 1 | 0.1 |

| Seek help from mental health professionals | ||

| Never | 675 | 88.1 |

| Used to | 77 | 10.1 |

| currently | 14 | 1.8 |

| having seen a psychiatrist in the past 12 months | 34 | 4.4 |

| Diagnosed with physical issues | 15 | 2.0 |

| Diagnosed with mental health issues | 36 | 4.7 |

| Item | a | b1 | Infit MSE | Outfit MSE | Loadings | h2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDE1 | 0.7835 | 1.0260 | 68.29 | 68.29 | 0.418 | 0.175 |

| SDE2 | 1.6577 | 1.2605 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.698 | 0.487 |

| SDE3 | 1.7728 | 2.1884 | 1.31 | 1.31 | 0.721 | 0.520 |

| SDE4 | 5.3100 | 0.1791 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.952 | 0.907 |

| SDE5 | 3.0075 | 0.3081 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.870 | 0.757 |

| KMO measure of sampling adequacy | 0.676 | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | Approx. chi-square | 665.457 |

| df | 10 | |

| Sig. | <0.001 |

| Variables | SDE ≥ 2 | VIF | SCOFF ≥ 2 | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | ||||

| Female | 0.922 *** | 1.062 | 0.709 ** | 1.062 |

| Age | −0.040 | 1.043 | 0.034 | 1.043 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.086 *** | 3.160 | 0.070 * | 3.160 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 0.005 | 3.232 | 0.331 *** | 3.232 |

| Childhood trauma | 0.126 | 1.217 | 0.221 * | 1.217 |

| visited a psychiatrist in the past 12 months | −0.276 | 1.154 | 0.144 | 1.154 |

| Constant | −0.738 | −3.520 ** | ||

| Nagelkerke (pseudo R2) | 0.235 | 0.276 | ||

| β | 0.180 | 0.218 | ||

| N | 766 | 766 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheung, T.Y.C.; Wong, M.Y.C.; Huang, C.H.O.; Lam, S.K.K.; Uludag, K.; Choi, M.S.J.; Huang, S.-Y.; Fung, H.W. Using the Chinese Version of the Screen for Disordered Eating to Assess Disordered Eating: Reliability, Validity and Correlates. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2458. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192458

Cheung TYC, Wong MYC, Huang CHO, Lam SKK, Uludag K, Choi MSJ, Huang S-Y, Fung HW. Using the Chinese Version of the Screen for Disordered Eating to Assess Disordered Eating: Reliability, Validity and Correlates. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2458. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192458

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheung, Tin Yan Cherry, Ming Yu Claudia Wong, Chak Hei Ocean Huang, Stanley Kam Ki Lam, Kadir Uludag, Ming Sing Jessica Choi, Shan-Yan Huang, and Hong Wang Fung. 2025. "Using the Chinese Version of the Screen for Disordered Eating to Assess Disordered Eating: Reliability, Validity and Correlates" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2458. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192458

APA StyleCheung, T. Y. C., Wong, M. Y. C., Huang, C. H. O., Lam, S. K. K., Uludag, K., Choi, M. S. J., Huang, S.-Y., & Fung, H. W. (2025). Using the Chinese Version of the Screen for Disordered Eating to Assess Disordered Eating: Reliability, Validity and Correlates. Healthcare, 13(19), 2458. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192458