Health Literacy and Sociodemographic Determinants of Cyberchondria: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Outpatients of a University Hospital in Turkey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

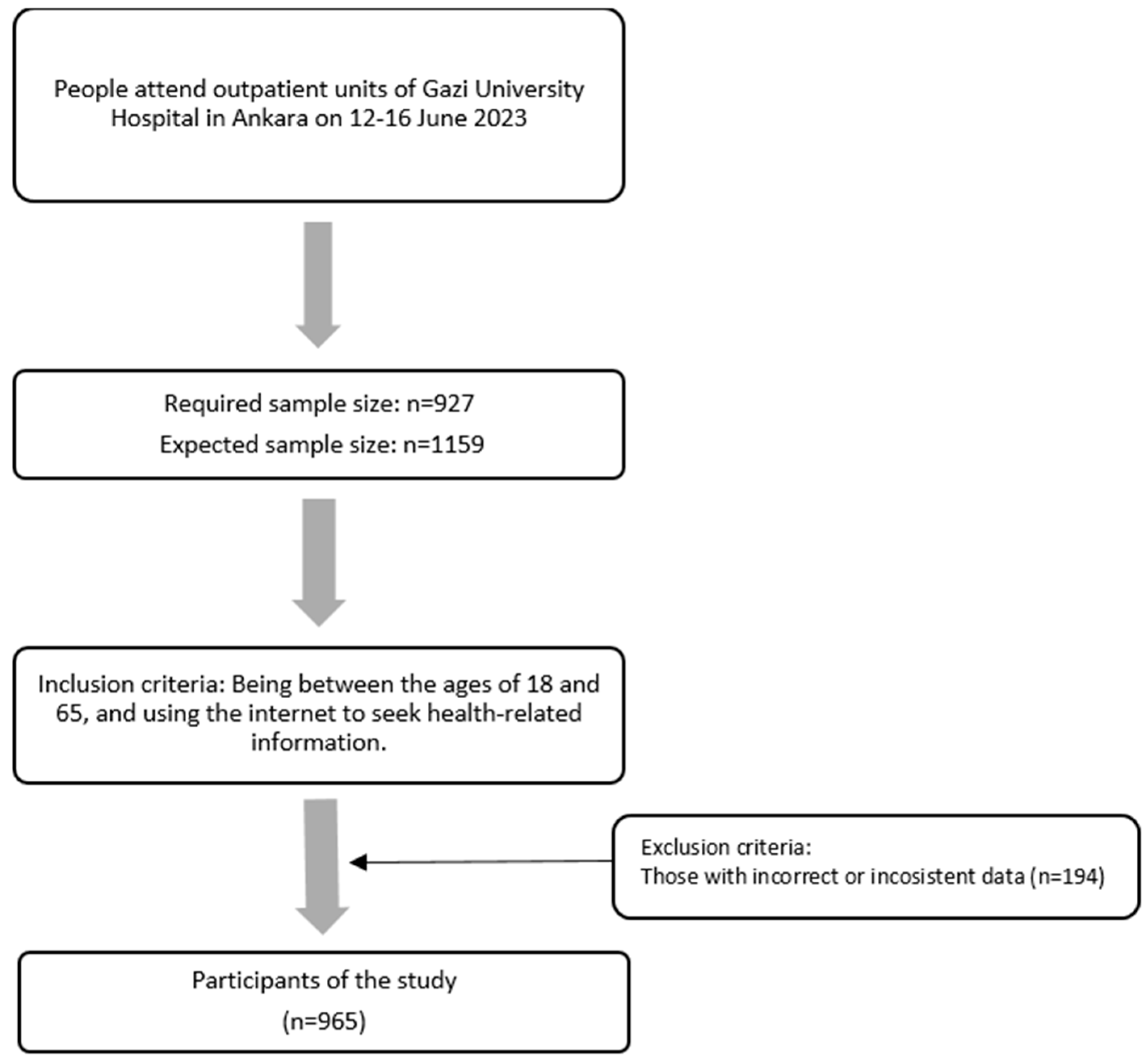

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Implementation

2.3. Data

2.3.1. Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS)

2.3.2. Short-Form Health Literacy Scale (HLS-SF)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

HL: Health Literacy; CSS: Cyberchondria Severity Scale

4. Discussion

4.1. The Association of Socio-Demographic Variables with Cyberchondria

4.2. The Association of Certain Health-Related Characteristics with Cyberchondria

4.3. The Association of Health Literacy with Cyberchondria

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| eHL | e-health literacy |

| HLS-SF | Short Form Health Literacy Scale |

| CSS | Cyberchondria Severity Scale |

References

- Lambert, S.D.; Loiselle, C.G. Health information—Seeking behavior. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkiewicz, K.L. The İmpact of Cyberchondria on Doctor-Patient Communication; The University of Wisconsin: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, W.; Amuta, A.O.; Jeon, K.C. Health information seeking in the digital age: An analysis of health information seeking behavior among US adults. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 1302785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaid, D.; Park, A.L. Online health: Untangling the web. In Bupa Health Pulse; Bupa: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Muse, K.; McManus, F.; Leung, C.; Meghreblian, B.; Williams, J.M.G. Cyberchondriasis: Fact or fiction? A preliminary examination of the relationship between health anxiety and searching for health information on the Internet. J. Anxiety Disord. 2012, 26, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcevic, V.; Berle, D. Cyberchondria: Towards a better understanding of excessive health-related Internet use. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2013, 13, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Naeem, S.; Kamel Boulos, M.N. COVID-19 misinformation online and health literacy: A brief overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Bie, B.; Park, S.E.; Zhi, D. Social media and outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases: A systematic review of literature. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, 962–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.W.; Horvitz, E. Experiences with Web Search on Medical Concerns and Self Diagnosis. In Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, Virtual, 14–18 November 2009; Volume 2009, p. 696. [Google Scholar]

- Uzun, S.U.; Zencir, M. Reliability and validity study of the Turkish version of cyberchondria severity scale. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhan, N.; Tutgun-ünal, A.; Ekinci, Y. Yeni kuşak hastalığı siberkondri: Yeni medya çağında kuşakların siberkondri düzeyleri ile sağlık okuryazarlığı ilişkisi. OPUS Int. J. Soc. Res. 2021, 17, 4253–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Khait, A.; Mrayyan, M.T.; Al-Rjoub, S.; Rababa, M.; Al-Rawashdeh, S. Cyberchondria, anxiety sensitivity, hypochondria, and internet addiction: Implications for mental health professionals. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 27141–27152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubeen Akhtar, T.F. Exploring cyberchondria and worry about health among individuals with no diagnosed medical condition. JPMA 2019, 70, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Makarla, S.; Gopichandran, V.; Tondare, D. Prevalence and correlates of cyberchondria among professionals working in the information technology sector in Chennai, India: A cross-sectional study. J. Postgrad. Med. 2019, 65, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathes, B.M.; Norr, A.M.; Allan, N.P.; Albanese, B.J.; Schmidt, N.B. Cyberchondria: Overlap with health anxiety and unique relations with impairment, quality of life, and service utilization. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 261, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altındiş, S.; İnci, M.B.; Aslan, F.G.; Altındiş, M. Üniversite çalışanlarında siberkondria düzeyleri ve ilişkili faktörlerin incelenmesi. Sak. Tıp Derg. 2018, 8, 359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Aktan, E. Üniversite öğrencilerinin sosyal medya bağımlılık düzeylerinin çeşitli değişkenlere göre incelenmesi. Erciyes İletişim Derg. 2018, 5, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallón-Botaya, R.; Méndez-López, F.; Oliván-Blázquez, B.; Carlos Silva-Aycaguer, L.; Lerma-Irureta, D.; Bartolomé-Moreno, C. Effectiveness of health literacy interventions on anxious and depressive symptomatology in primary health care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1007238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Division of health promotion, education and communications health education and health promotion unit. In Health Promotion Glossary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Özer, Ö.; Özmen, S.; Özkan, O. Investigation of the effect of cyberchondria behavior on e-health literacy in healthcare workers. Hosp. Top. 2023, 101, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Brand, H. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakan, A.B.; Yıldız, M. 21–64 yaş grubundaki bireylerin sağlık okuryazarlık düzeylerinin belirlenmesine ilişkin bir çalışma. Sağlık Toplum 2019, 29, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Demirli, P. Bireylerin Sağlık Okuryazarlığı Üzerine bir Araştırma: Edirne İli Örneği. Master’s Thesis, Trakya Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Sağlık Kurumları Yöneticiliği Anabilim Dalı Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Edirne, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tanrıöver, M.D.; Yıldırım, H.H.; Ready, F.N.D.; Çakır, B.; Akalın, H.E. Sağlik okuryazarliği araştirmasi. Sağlık-Sen Yayınları 2014, 6, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı Sağlığın Geliştirilmesi Genel Müdürlüğü, Türkiye Sağlık Okuryazarlığı Düzeyi ve İlişkili Faktörleri Araştırması, Yayın No:1298, Ankara, Aralık 2024. Available online: https://dosyamerkez.saglik.gov.tr/Eklenti/50280/0/turkiye-saglik-okuryazarligi-ve-iliskili-faktorleri-arastirmasipdf.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Gültekin, İ.E. Aile Hekimliği Polikliniğine Başvuran Hastalarda Siberkondri Düzeyleri ve Sağlık Okuryazarlığı İle İlişkisi (Yayınlanmamış Uzmanlık Tezi); Çanakkale On Sekiz Mart Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi: Çanakkale, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Jiang, S. Linking the pathway from exposure to online vaccine information to cyberchondria during the COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated mediation model. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2022, 25, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcevic, V. Keeping Dr. Google under control: How to prevent and manage cyberchondria. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.H.; Starcevic, V. Cyberchondria in Older Adults and Its Relationship with Cognitive Fusion, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Mental Well-Being: Mediation Analysis. JMIR Aging 2025, 8, e70302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzi, H.; Akca, A.; Sultan, A. Siberkondri Ciddiyet Ölçeği-Kısa Formu: Psikometrik Bir Çalışma. Genel Tıp Derg. 2024, 34, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, G.; Starcevic, V.; Scalone, A.; Cavallo, J.; Musetti, A.; Schimmenti, A. The doctor is in (ternet): The mediating role of health anxiety in the relationship between somatic symptoms and cyberchondria. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElroy, E.; Shevlin, M. The development and initial validation of the cyberchondria severity scale (CSS). J. Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, T.V.; Aringazina, A.; Kayupova, G.; Nurjanah, F.; Pham, T.V.; Pham, K.M.; Truong, T.Q.; Nguyen, K.T.; Oo, W.M.; Chang, P.W. Development and validation of a new short-form health literacy instrument (HLS-SF12) for the general public in six Asian countries. HLRP Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2019, 3, e91–e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, S.K.; Eskici, G. Sağlık okuryazarlığı ölçeği-kısa form ve dijital sağlıklı diyet okuryazarlığı ölçeğinin türkçe formunun geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. İzmir Katip Çelebi Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilim. Fakültesi Derg. 2021, 6, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barke, A.; Bleichhardt, G.; Rief, W.; Doering, B.K. The Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS): German validation and development of a short form. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 23, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vismara, M.; Vitella, D.; Biolcati, R.; Ambrosini, F.; Pirola, V.; Dell’Osso, B.; Truzoli, R. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on searching for health-related information and cyberchondria on the general population in Italy. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 754870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Negra, J.M.; Paiva, S.M.; Baptista, A.S.; Cruz, A.J.S.; Pinho, T.; Abreu, M.H. Cyberchondria and associated factors among Brazilian and Portuguese dentists. Acta Odontol. Latinoam. 2022, 35, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertaş, H.; Kıraç, R.; Ünal, S.N. Sağlık bilimleri fakültesi öğrencilerinin siberkondri düzeyleri ve ilişkili faktörlerin incelenmesi. OPUS Int. J. Soc. Res. 2020, 15, 1746–1764. [Google Scholar]

- Erdoğan, T.; Aydemir, Y.; Aydın, A.; İnci, M.B.; Ekerbiçer, H.; Muratdağı, G.; Kurban, A. İnternet ve televizyonda sağlık bilgisi arama davranışı ve ilişkili faktörler. Sak. Tıp Derg. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.C.; Liu, F.; He, H.Y.; Luo, T.; Dai, P.P.; Xie, W.Z.; Luo, A.J. The status and influencing factors of cyberchondria during the COVID-19 epidemic. A cross-sectional study in Nanyang city of China. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 712703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güleşen, A.; Beydağ, K.D. Cryberchondria level in women with heart disease and affecting factors. Verus J. 2020, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, N.; Saperstein, S.; Pleis, J. Using the internet for health-related activities: Findings from a national probability sample. J. Med. Internet Res. 2009, 11, e1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, R.E. Influences, usage, and outcomes of Internet health information searching: Multivariate results from the Pew surveys. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2006, 75, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, S.; Naqvi, I. Prevalence Of Cyberchondria Among University Students: An Emerging Challenge Of The 21st Century. JPMA. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2023, 73, 1634–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varer Akpinar, C.; Mandiracioglu, A.; Ozvurmaz, S.; Kurt, F.; Koc, N. Cyberchondria and COVID-19 anxiety and internet addiction among nursing students. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 2406–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teken, M.T. Bir Üniversite Hastanesine Başvuran Hastalarda Siberkondri ve Sağlık Okuryazarlığı Düzeylerinin Değerlendirilmesi. Master’s Thesis, Necmettin Erbakan University, Konya, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kobryn, M.; Duplaga, M. Does health literacy protect against Cyberchondria: A cross-sectional study? Telemed. e-Health 2024, 30, e1089–e1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadgarinejad, A.; Nazarihermoshi, N.; Hematichegeni, N.; Jazaiery, M.; Yousefishad, S.; Mohammadian, H.; Cheraghi, M. Relationship between health literacy and generalized anxiety disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in Khuzestan province, Iran. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1294562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Hendawi, N.E.; El-Ashry, A.M.; Mohammed, M.S. The relationship between cyberchondria and health literacy among first-year nursing students: The mediating effect of health anxiety. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, S.; Mushtaque, I. The moderating role of health literacy and health promoting behavior in the relationship among health anxiety, emotional regulation, and cyberchondria. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Zayat, A.; Namnkani, S.A.; Alshareef, N.A.; Mustfa, M.M.; Eminaga, N.S.; Algarni, G.A. Cyberchondria and its association with smartphone addiction and electronic health literacy among a Saudi population. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Zheng, T.; Ding, L.; Zhang, X. Exploring associations between eHealth literacy, cyberchondria, online health information seeking and sleep quality among university students: A cross-section study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, F.; Ciğerci, K. Siberkondri ve e-sağlık okuryazarlığı arasındaki ilişki. Gümüşhane Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2022, 11, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n = 965 | n (%) | Cyberchondria Severity Scale Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | p | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 531(55.0) | 85.9 ± 20.5 | 0.001 |

| Male | 434 (45.0) | 81.8 ± 18.1 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 451 (46.7) | 85.0 ± 19.4 | 0.183 |

| Single | 514 (53.3) | 83.3 ± 19.7 | |

| Educational Status | |||

| Elementary school graduate and below | 38 (3.9) | 83.3 ± 22.2 | 0.003 a–b: 0.002 |

| Middle school graduate | 54 (5.6) | 86.8 ± 20.5 | |

| High school graduate a | 318 (33.0) | 87.0 ± 19.2 | |

| University graduate or above b | 555 (57.5) | 82.1 ± 19.3 | |

| Monthly Income Status of the Household | |||

| My expenses exceed my income | 229 (23.7) | 83.5 ± 19.6 | 0.276 |

| My income equals my expenses | 414 (42.9) | 85.2 ± 19.7 | |

| My income exceeds my expenses | 322 (33.4) | 83.0 ± 19.4 | |

| Chronic Illness Status | |||

| Yes | 318 (33.0) | 87.2 ± 20.1 | 0.001 |

| No | 647 (67.0) | 82.5 ± 19.1 | |

| Presence of Chronic Disease in the Family | |||

| Yes | 581 (60.2) | 84.2 ± 19.4 | 0.813 |

| No | 384 (39.8) | 83.9 ± 20.0 | |

| Perceived Health Status | |||

| Very Bad/Bad a | 48 (5.0) | 97.4 ± 21.3 | <0.001 a–b: <0.001 |

| Middle b | 236 (24.5) | 84.6 ± 19.4 | |

| Good b | 507 (52.5) | 84.1 ± 19.1 | |

| Very Good b | 174 (18.0) | 79.7 ± 19.1 | |

| Most Frequent Use of the Internet When Accessing Health-Related Information | |||

| No | 477 (49.4) | 80.8 ± 19.0 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 488 (50.6) | 87.2 ± 19.6 | |

| n = 965 | Age | Health Literacy (HL) Scale Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | r | 1 | |

| p | |||

| Health Literacy (HL) Scale Score | r | −0.229 * | 1 |

| p | <0.001 | ||

| Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS) Score | r | 0.033 | −0.165 * |

| p | 0.312 | <0.001 | |

| CSS Compulsion Subscale | r | −0.003 | −0.244 * |

| p | 0.920 | <0.001 | |

| CSS Distress Subscale | r | 0.063 | −0.186 * |

| p | 0.049 | <0.001 | |

| CSS Excessiveness Subscale | r | −0.054 | 0.012 |

| p | 0.092 | 0.704 | |

| CSS Reassurance Subscale | r | 0.151 * | −0.041 |

| p | <0.001 | 0.203 | |

| CSS Mistrust Of Medical Professional Subscale | r | −0.042 | −0.291 * |

| p | 0.192 | <0.001 | |

| MODEL | Unstandardized Coefficients B (Std. Error) | Standardized Coefficients Beta | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CONSTANT | 96.264 (2.433) | <0.001 | |

| Health Literacy Score (HLS) | −0.376 (0.072) | −0.165 | <0.001 | |

| 2 | CONSTANT | 94.039 (2.510) | <0.001 | |

| Health Literacy Score (HLS) | −0.378 (0.072) | −0.166 | <0.001 | |

| Gender (ref. male) | 4.167 (1.244) | 0.106 | 0.001 | |

| 3 | CONSTANT | 101.180 (3.124) | <0.001 | |

| Health Literacy Score (HLS) | −0.329 (0.073) | −0.144 | <0.001 | |

| Gender (ref. male) | 4.095 (1.236) | 0.104 | 0.001 | |

| Perceived Health Status (ref. very bad/bad) | −3.065 (0.808) | −0.121 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Özbaş, C.; Yıldız, E.T.; Tüzün, H.; Kara Çiğdem, A.G.; Uğraş Dikmen, A. Health Literacy and Sociodemographic Determinants of Cyberchondria: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Outpatients of a University Hospital in Turkey. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2445. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192445

Özbaş C, Yıldız ET, Tüzün H, Kara Çiğdem AG, Uğraş Dikmen A. Health Literacy and Sociodemographic Determinants of Cyberchondria: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Outpatients of a University Hospital in Turkey. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2445. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192445

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖzbaş, Cansu, Enes Talha Yıldız, Hakan Tüzün, Ayşen Gülçin Kara Çiğdem, and Asiye Uğraş Dikmen. 2025. "Health Literacy and Sociodemographic Determinants of Cyberchondria: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Outpatients of a University Hospital in Turkey" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2445. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192445

APA StyleÖzbaş, C., Yıldız, E. T., Tüzün, H., Kara Çiğdem, A. G., & Uğraş Dikmen, A. (2025). Health Literacy and Sociodemographic Determinants of Cyberchondria: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Outpatients of a University Hospital in Turkey. Healthcare, 13(19), 2445. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192445