Barriers and Predictors of HPV Vaccine Uptake Among Female Medical Students in Saudi Arabia: A Multi-Center Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the level of awareness and knowledge regarding HPV infection and its vaccine among female medical students in Saudi Arabia?

- What is the rate of HPV vaccine uptake among this population?

- What are the most commonly reported barriers to HPV vaccine acceptance among female medical students?

- Which demographic, academic, or knowledge-related factors significantly predict HPV vaccine uptake?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting

2.3. Sample and Sampling Technique

2.4. Data Collection Tools

- 1.

- Demographic and Academic Information:

- 2.

- HPV Infection Knowledge Assessment Tool:

- 3.

- HPV Vaccine Knowledge Assessment Tool:

- 4.

- HPV Vaccine Acceptability and Attitudes Tool:

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

2.6. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

Participant Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice/Policy

4.2. Future Research

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elbus, L.M.S.; Mostafa, M.G.; Mahmoud, F.Z.; Shaban, M.; Mahmoud, S.A. Nurse Managers’ Managerial Innovation and It’s Relation to Proactivity Behavior and Locus of Control among Intensive Care Nurses. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burd, E.M. Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamolratanakul, S.; Pitisuttithum, P. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Efficacy and Effectiveness against Cancer. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Biswas, M.; Jose, T. HPV Vaccine: Current Status and Future Directions. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2015, 71, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellingson, M.K.; Sheikha, H.; Nyhan, K.; Oliveira, C.R.; Niccolai, L.M. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Effectiveness by Age at Vaccination: A Systematic Review. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2023, 19, 2239085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei, G.K.; Kyei, E.F.; Ansong, R. HPV Vaccine Hesitancy and Uptake: A Conceptual Analysis Using Rodgers’ Evolutionary Approach. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 2368–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangelosi, G.; Sacchini, F.; Mancin, S.; Petrelli, F.; Amendola, A.; Fappani, C.; Sguanci, M.; Morales Palomares, S.; Gravante, F.; Caggianelli, G. Papillomavirus Vaccination Programs and Knowledge Gaps as Barriers to Implementation: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2025, 13, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsbeih, G. HPV Infection in Cervical and Other Cancers in Saudi Arabia: Implication for Prevention and Vaccination. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faqih, L.; Alzamil, L.; Aldawood, E.; Alharbi, S.; Muzzaffar, M.; Moqnas, A.; Almajed, H.; Alghamdi, A.; Alotaibi, M.; Alhammadi, S.; et al. Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus Infection and Cervical Abnormalities among Women Attending a Tertiary Care Center in Saudi Arabia over 2 Years. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Alkhenizan, A.; McWalter, P.; Qazi, N.; Alshmassi, A.; Farooqi, S.; Abdulkarim, A. Attitudes and Perceptions towards HPV Vaccination among Young Women in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2016, 23, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard-Eaglin, A.; McFarland, M.L. Applying Cultural Intelligence to Improve Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 57, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekezie, W.; Awwad, S.; Krauchenberg, A.; Karara, N.; Dembiński, Ł.; Grossman, Z.; del Torso, S.; Dornbusch, H.J.; Neves, A.; Copley, S.; et al. Access to Vaccination among Disadvantaged, Isolated and Difficult-to-Reach Communities in the WHO European Region: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Tiwari, S.K.; Dubey, V.; Tripathi, P.; Pandey, P.; Singh, A.; Choudhary, N.P.S. Knowledge, Attitude, and Reasons for Non-Uptake of Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination among Nursing Students. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badur, S.; Öztürk, S.; Ozakay, A.; Khalaf, M.; Saha, D.; Van Damme, P. A Review of the Experience of Childhood Hepatitis A Vaccination in Saudi Arabia and Turkey: Implications for Hepatitis A Control and Prevention in the Middle East and North African Region. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 3710–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzamil, Y.; Almeshari, M.; Alyahyawi, A.; Abanomy, A.; Al-Thomali, A.W.; Alshomar, B.; Althomali, O.W.; Barnawi, H.; Bazaid, A.S.; Bin Sheeha, B. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of the Saudi Population toward COVID-19 Vaccination: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicine 2023, 102, e35360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.P.; Wong, P.-F.; Megat Hashim, M.M.A.A.; Han, L.; Lin, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Zimet, G.D. Multidimensional Social and Cultural Norms Influencing HPV Vaccine Hesitancy in Asia. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020, 16, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farsi, N.J.; Baharoon, A.H.; Jiffri, A.E.; Marzouki, H.Z.; Merdad, M.A.; Merdad, L.A. Human Papillomavirus Knowledge and Vaccine Acceptability among Male Medical Students in Saudi Arabia. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 1968–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, S.S.; Alshehri, S.M.; Alkhateeb, M.A.; Alsudias, L.S. Assessing Saudi Women’s Awareness about Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Their Susceptibility to Receive the Vaccine. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2024, 20, 2395086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, A.A. Exploring Factors Associated with Awareness, Willingness, and HPV Vaccine Uptake among Female Health Sciences University Students in Saudi Arabia. Univers. J. Public Health 2025, 13, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhomayani, K.; Bukhary, H.; Aljuaid, F.; Alotaibi, T.A.; Alqurashi, F.S.; Althobaiti, K.; Althobaiti, N.; Althomali, O.; Althobaiti, A.; Aljuaid, M.M.; et al. Gender Preferences in Healthcare: A Study of Saudi Patients’ Physician Preferences. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2025, 19, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, S.E.; Kenzie, L.; Letendre, A.; Bill, L.; Shea-Budgell, M.; Henderson, R.; Barnabe, C.; Guichon, J.R.; Colquhoun, A.; Ganshorn, H.; et al. Barriers and Supports for Uptake of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in Indigenous People Globally: A Systematic Review. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0001406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Narayan, E.; Ahmed, I.; Hussen Bule, M. Inadequate cervical cancer testing facilities in Pakistan: A major public health concern. Int. J. Surg. Glob. Health 2023, 6, e0336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algaadi, S.A.; Aldhafiri, H.J.; Alsubhi, R.S.; Almakrami, M.; Aljamaan, N.H.; Almulhim, Y.A. The Saudi Population’s Knowledge and Attitude Towards Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection and Its Vaccination. Cureus 2024, 16, e58427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldawood, E.; Alzamil, L.; Dabbagh, D.; Hafiz, T.A.; Alharbi, S.; Alfhili, M.A. The Effect of Educational Intervention on Human Papillomavirus Knowledge among Male and Female College Students in Riyadh. Medicina 2024, 60, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, T. Human Papillomavirus and Its Vaccination: Knowledge and Attitudes among Female University Students in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsulami, F.T. Exploring the Impact of Knowledge about the Human Papillomavirus and Its Vaccine on Perceived Benefits and Barriers to Human Papillomavirus Vaccination among Adults in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShamlan, N.; AlOmar, R.; AlAbdulKader, A.; Shafey, M.; AlGhamdi, F.; Aldakheel, A.; AlShehri, S.; Felemban, L.; AlShamlan, S.; Al Shammari, M. HPV Vaccine Uptake, Willingness to Receive, and Causes of Vaccine Hesitancy: A National Study Conducted in Saudi Arabia Among Female Healthcare Professionals. Int. J. Women’s Health 2024, 16, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, S.; Abraham, A.; Maisonneuve, P.; Jithesh, A.; Chaabna, K.; al Janahi, R.; Sarker, S.; Hussain, A.; Rao, S.; Lowenfels, A.B.; et al. HPV Infection and Vaccination: A Cross-Sectional Study of Knowledge, Perception, and Attitude to Vaccine Uptake among University Students in Qatar. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xu, T.; Wu, J.; Sun, C.; Han, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Qiao, C.; Tao, X. Exploring Factors Influencing Awareness and Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus in Chinese College Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2024, 20, 2388347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.A.; Alghamdi, H.A. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Vaccination Among Parents in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15, e41721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuhebany, N.; Alowais, S.A.; Aldairem, A.; Almohareb, S.N.; Bin Saleh, K.; Kahtani, K.M.; Alnashwan, L.I.; Alay, S.M.; Alamri, M.G.; Alhathlol, G.K.; et al. Identifying Gaps in Vaccination Perception after Mandating the COVID-19 Vaccine in Saudi Arabia. Vaccine 2023, 41, 3611–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderslott, S.; Enria, L.; Bowmer, A.; Kamara, A.; Lees, S. Attributing Public Ignorance in Vaccination Narratives. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 307, 115152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampetakis, L.A.; Melas, C. The Health Belief Model Predicts Vaccination Intentions against COVID-19: A Survey Experiment Approach. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2021, 13, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuetzle, S.C.W.; Willis, M.; Barnowska, E.J.; Bonkass, A.-K.; Fastenau, A. Factors Influencing Vaccine Hesitancy toward Non-Covid Vaccines in South Asia: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivenes Lafontan, S.; Jones, F.; Lama, N. Exploring Comprehensive Sexuality Education Experiences and Barriers among Students, Teachers and Principals in Nepal: A Qualitative Study. Reprod. Health 2024, 21, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellin, M.R.; Abdul Hamid, S.H.; Mohd Arifin, S.R.; Hasan, H.; Huriah, T.; Othman, S.; Mohd Zain, N. A Culturally-Sensitive Approach to Sexual and Reproductive Health Education: A Critical Review of a Parenting Sexuality Book. J. Health Qual. Life 2025, 5, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onasoga, O.A.; Dosumu, T.O.; Folarin, A.O.; Shittu, B.M. Knowledge and Uptake of Human Papilloma Virus Vaccine among Female Undergraduate Students in North-Central, Nigeria: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2025, 13, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukeshtayeva, K.; Yerdessov, N.; Zhamantayev, O.; Takuadina, A.; Kayupova, G.; Dauletkaliyeva, Z.; Bolatova, Z.; Davlyatov, G.; Karabukayeva, A. Understanding Students’ Vaccination Literacy and Perception in a Middle-Income Country: Case Study from Kazakhstan. Vaccines 2024, 12, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher, S.; Fakhoury, H.M.A.; Tamim, H.; Saleem, R.; Alshammary, B.S.; Alzahrani, R.J.; Alzahrani, N.M.; Geraat, E.A.; Abolfotouh, M.; Jawdat, D. Attitudes Toward COVID-19 Vaccination and Clinical Trials Among Saudi University Students. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, A.; Pateman, M.; Fullerton, M.M.; Chen, H.M.; Bailey, L.; Houle, S.; Davidson, S.; Constantinescu, C. Vaccine Hesitancy Educational Tools for Healthcare Providers and Trainees: A Scoping Review. Vaccine 2023, 41, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, B.A.; Nonzee, N.J.; Tieu, L.; Pedone, B.; Cowgill, B.O.; Bastani, R. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination in the Transition between Adolescence and Adulthood. Vaccine 2021, 39, 3435–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.L.; Jensen, J.D.; Scherr, C.L.; Brown, N.R.; Christy, K.; Weaver, J. The Health Belief Model as an Explanatory Framework in Communication Research: Exploring Parallel, Serial, and Moderated Mediation. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, V.A.; Nogueira, D.L.; Delgado, D.; Valdez, M.J.; Lucero, D.; Hernandez Nieto, A.; Rodriguez-Cruz, N.; Lindsay, A.C. Misconceptions and Knowledge Gaps about HPV, Cervical Cancer, and HPV Vaccination among Central American Immigrant Parents in the United States. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2025, 21, 2494452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kbaier, D.; Kane, A.; McJury, M.; Kenny, I. Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media—Challenges and Mitigation Before, During, and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Literature Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e38786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, M.S.; Dunn, A.G.; Wiley, K.E.; Leask, J. How Organisations Promoting Vaccination Respond to Misinformation on Social Media: A Qualitative Investigation. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruwaili, A.N.; Alruwaili, M.; Ramadan, O.M.E.; Elsharkawy, N.B.; Abdelaziz, E.M.; Ali, S.I.; Shaban, M. Compassion Fatigue in Palliative Care: Exploring Its Comprehensive Impact on Geriatric Nursing Well-Being and Care Quality in End-of-Life. Geriatr. Nurs. 2024, 58, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, M.; Amer, F.G.M.; Shaban, M.M. The Impact of Nursing Sustainable Prevention Program on Heat Strain among Agricultural Elderly Workers in the Context of Climate Change. Geriatr. Nurs. 2024, 58, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaban, M.; Shaban, M.M.; Zaky, M.E.; Alanazi, M.A.; Ramadan, O.M.E.; Ebied, E.M.E.s.; Ghoneim, N.I.A.; Ali, S.I. Divine Resilience: Unveiling the Impact of Religious Coping Mechanisms on Pain Endurance in Arab Older Adults Battling Chronic Pain. Geriatr. Nurs. 2024, 57, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odongo, M. Health Communication Campaigns and Their Impact on Public Health Behaviors. J. Commun. 2024, 5, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed Ramadan, O.M.; Alruwaili, M.M.; Alruwaili, A.N.; Elsharkawy, N.B.; Abdelaziz, E.M.; Zaky, M.E.; Shaban, M.M.; Shaban, M. Nursing Practice of Routine Gastric Aspiration in Preterm Infants and Its Link to Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Is the Practice Still Clinically Relevant? BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisa, S.; Kisa, A. Religious Beliefs and Practices toward HPV Vaccine Acceptance in Islamic Countries: A Scoping Review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghalyini, B.; Zaidi, A.R.Z.; Meo, S.A.; Faroog, Z.; Rashid, M.; Alyousef, S.S.; Al-Bargi, Y.Y.; Albader, S.A.; Alharthi, S.A.A.; Almuhanna, H.A. Awareness and knowledge of human papillomavirus, vaccine acceptability and cervical cancer among college students in Saudi Arabia. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2024, 20, 2403844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L. Risk perception and trust in the relationship between knowledge and HPV vaccine hesitancy among female university students in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akande, O.W.; Akande, T.M. Human Papillomavirus vaccination amongst students in a tertiary institution in the Lagos metropolis. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2024, 31, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Wanderley, M.; Sobral, D.T.; de Azevedo Levino, L.; de Assis Marques, L.; Feijó, M.S.; Aragão, N.R.C. Students’ HPV vaccination rates are associated with demographics, sexuality, and source of advice but not level of study in medical school. Rev. Inst. Med. trop. S. Paulo 2019, 61, e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD, years) | 22.23 ± 1.69 | ||

| Nationality | Saudi | 242 | 98.4 |

| Non-Saudi | 4 | 1.6 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 236 | 95.9 |

| Married | 9 | 3.7 | |

| Divorced | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Academic Year | First-year | 36 | 14.6 |

| Second-year | 33 | 13.4 | |

| Third-year | 40 | 16.3 | |

| Fourth-year | 45 | 18.3 | |

| Fifth-year | 92 | 37.4 | |

| GPA | Excellent (4.50–5.00) | 150 | 61.0 |

| Very Good (3.75–4.49) | 82 | 33.3 | |

| Good (2.75–3.49) | 12 | 4.9 | |

| Pass (2.00–2.74) | 2 | 0.8 | |

| Smoking Status | Never | 217 | 88.2 |

| Current | 20 | 8.1 | |

| Former | 9 | 3.7 |

| Knowledge Level | Score Range | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | ≥13 | 84 | 41.2 |

| Moderate | 8–12 | 98 | 48.0 |

| Low | ≤7 | 22 | 10.8 |

| Knowledge Level | Score Range | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | ≥9 | 20 | 10.3 |

| Moderate | 6–8 | 82 | 42.3 |

| Low | ≤5 | 92 | 47.4 |

| Information Source | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Education (courses) | 175 | 85.8 |

| Media (TV, Social Media) | 73 | 35.8 |

| Internet (websites) | 64 | 31.4 |

| Healthcare Providers | 43 | 21.1 |

| Family/Friends | 36 | 17.6 |

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Previously Vaccinated | 56 | 22.8 |

| Interested in Vaccination | 171 | 69.5 |

| Barriers: (Multiple answers allowed) | ||

| Perceived unnecessary | 34 | 45.3 |

| Not sexually active | 31 | 41.3 |

| Safety concerns | 26 | 34.7 |

| Insufficient information | 21 | 28.0 |

| Lack of doctor recommendation | 15 | 20.0 |

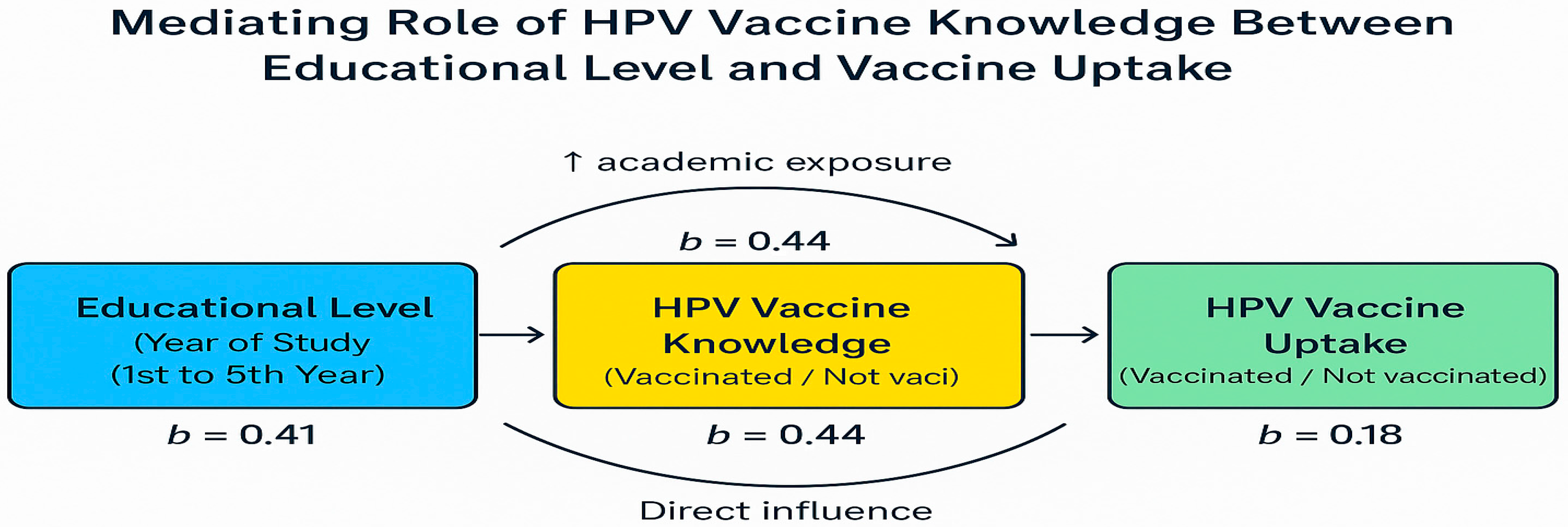

| Variables | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.12 | 0.95–1.32 | 0.162 |

| Second-year | 1.74 | 0.52–5.85 | 0.370 |

| Third-year | 3.21 | 1.05–9.79 | 0.042 * |

| Fourth-year | 4.28 | 1.47–12.46 | 0.008 * |

| Fifth-year | 5.92 | 2.15–16.30 | <0.001 * |

| HPV Vaccine Knowledge Score | 1.36 | 1.18–1.57 | <0.001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakhsh, H.; Ali Altamimi, S.; Aldosari, F.N.; Hatim Aljohani, L.; Abdulrahman Alali, S.; Ibrahim Almutlaq, N.; Alrusaini, N.K.; Munif Alshammari, S.; Abdulaziz Alsuhaibani, Y.; Abdulwahab Alshehri, S. Barriers and Predictors of HPV Vaccine Uptake Among Female Medical Students in Saudi Arabia: A Multi-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2408. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192408

Bakhsh H, Ali Altamimi S, Aldosari FN, Hatim Aljohani L, Abdulrahman Alali S, Ibrahim Almutlaq N, Alrusaini NK, Munif Alshammari S, Abdulaziz Alsuhaibani Y, Abdulwahab Alshehri S. Barriers and Predictors of HPV Vaccine Uptake Among Female Medical Students in Saudi Arabia: A Multi-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2408. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192408

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakhsh, Hanadi, Sarah Ali Altamimi, Falak Nasser Aldosari, Lujain Hatim Aljohani, Sarah Abdulrahman Alali, Nujud Ibrahim Almutlaq, Norah Khalid Alrusaini, Shuruq Munif Alshammari, Yara Abdulaziz Alsuhaibani, and Shatha Abdulwahab Alshehri. 2025. "Barriers and Predictors of HPV Vaccine Uptake Among Female Medical Students in Saudi Arabia: A Multi-Center Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2408. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192408

APA StyleBakhsh, H., Ali Altamimi, S., Aldosari, F. N., Hatim Aljohani, L., Abdulrahman Alali, S., Ibrahim Almutlaq, N., Alrusaini, N. K., Munif Alshammari, S., Abdulaziz Alsuhaibani, Y., & Abdulwahab Alshehri, S. (2025). Barriers and Predictors of HPV Vaccine Uptake Among Female Medical Students in Saudi Arabia: A Multi-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(19), 2408. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192408