1. Introduction

Menstruation is a normal biological process experienced by millions of women and young girls worldwide every month. Menarche refers to the beginning of a woman’s reproductive years and is generally recognized as the transition to full adult female status in most societies [

1]. Menstruation is the common source of various taboos and rituals in all traditional cultures. There are many myths and cultural misperceptions about menstruation that persist to this day [

2].

In many societies, menstrual myths cause women to postpone personal care, feel ashamed, be left alone, have their physical activities inhibited, be stigmatized as dirty or sick, and negatively affect their spiritual lives. For example: during menstruation, Indian women do not wash their bodies, do not apply oil/cream, and do not apply make-up to their eyes. Until the end of menstruation, they sleep on the floor and do not sleep during the day, do not eat meat, cannot touch fire, cannot look at the planets and cannot clean their teeth [

3]. In Ethiopia, girls perceive menstruation as dirty and shameful. They should not talk to men during menstruation, should not tell anyone that they are menstruating, and should live in secret [

4]. In Zambia, girls are not asked to add salt to the food during menstruation because it is believed that the person who eats the food will have a chronic cough. Zambian women believe that menstrual bleeding will last longer when they do physical activity during menstruation, and that witches and satanists will use menstrual blood to bewitch and sterilize them [

5]. In Turkish society, while birth, circumcision and wedding events are spoken aloud in public, talking about menstruation is perceived as shameful. In Turkish society, there is a generally negative attitude towards menstruation and persistent myths. Menstruating women generally express themselves as “I got dirty” or “I got sick” and must perform a purification ritual at the end of menstruation [

6]. In many societies, myths about menstruation affect girls’ and women’s emotional states, mental functions, lifestyles and most importantly their health. Menstrual myths in different cultures cause girls to drop out of school, prevent them from transitioning to work, cause stigma within society, and lead to social isolation [

7]. Menstrual myths restrict women’s daily activities and deprive them of hygienic health practices leading to negative consequences such as infection [

8]. Ameade and Garti (2016) [

9] reported in their research that girls are afraid and panic when they start their period. This suggests that girls lack knowledge about menstruation, affecting their general health and potentially leading to school absences. Chothe et al. (2014) [

10] reported in their study that female students lack knowledge about the symptoms, irregularities, and myths surrounding menstruation. They reported that they do not consult a healthcare professional for menstrual irregularities and dysmenorrhea, but rather attempt to manage their problems themselves with traditional medications. This suggests that female students face difficulties accessing healthcare services. Research shows that during menstruation, adolescent girls change their eating habits, avoid cold foods, and limit their activities. This negatively impacts both their overall health and their growth and development [

11,

12]. Furthermore, one study found that menstruation is perceived as a shameful event, leading to social exclusion, isolation, and stigmatization [

13]. Not showering during menstruation leads to poor hygiene and urogenital infections. Persistently, this situation leads to recurrent infections and sexual and reproductive health problems [

7]. In their research, Akpenpuun and Azende (2014) [

14] stated that girls’ knowledge level about menstruation is low, the myths they believe are many, and this is especially worrying in terms of reproductive health.

The difficulty of addressing socio-cultural myths, taboos and beliefs about menstruation prevents girls/women from receiving information on menstruation and reproductive health. In order to improve women’s/girls’ reproductive health, it is important to know their attitudes towards myths about menstruation. This is necessary in order to prepare strategies to combat myths. It is important to know menstrual myths and attitudes towards them in order for women and girls of reproductive age to experience menstruation healthily. Menstrual myths harm the physiological, psychological and spiritual health of menstruating people. To raise awareness of myths adopted by society and healthy practices during menstruation, individuals and families, healthcare professionals, educators, governments, politicians, and civil society organizations need to understand menstrual myths and their attitudes. The most reliable way to quantify people’s attitudes toward menstrual myths is through scales. During the literature review, it was determined that menstruation-related scales generally assess attitudes, beliefs, and the effects of menstruation [

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, a limited number of scales have been found to measure menstrual myths. The menstrual myths scale in the literature measures menstrual practices, beliefs, and personal hygiene practices [

19]. However, this scale aims to measure myths related to menstrual information, menstrual stigmatization, menstrual privacy, menstrual hygiene, and menstruation education. Having multiple scales on the same topic would allow researchers to examine the topic more comprehensively. Furthermore, the diversity in the number of scale items, their adaptability to different cultures, and the suitability of the target population would allow for more flexible and appropriate measurements across different samples. Having different scales on the same topic would facilitate comparative analysis and provide more detailed information about their psychometric properties. This scale identifies menstrual myths and attitudes, and is believed to facilitate researchers in taking measures to address menstrual myths to improve women’s health and ensure women’s educational and employment continuity. In this context, the aim of this study was to develop a measurement tool to determine the attitudes of women of reproductive age toward menstrual myths.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to develop a reliable and valid scale to determine women’s attitudes toward menstrual myths.

Two criteria are needed to develop a new scale. These criteria are validity and reliability. Construct validity refers to the degree to which a scale accurately represents the construct being measured [

36]. In this study, confirmatory and exploratory factor analysis were used to assess construct validity. Factor analysis is widely used to assess construct validity and to test whether items load on different factors [

37]. In factor analysis of a scale, the KMO test should first be applied to determine the adequacy and appropriateness of the sample size, and the Bartlett sphericity test should be applied to determine the relationship between variables [

36,

37,

38,

39]. In factor analysis, the KMO value must be greater than 0.5 [

39,

40], and this developed scale found it to be greater than 0.90. Accordingly, the research sample is perfectly adequate for factor analysis. The Bartlett test of sphericity (χ

2 = 2876.480; SD = 496,

p < 0.05) indicates that the variables are related and suitable for factor analysis.

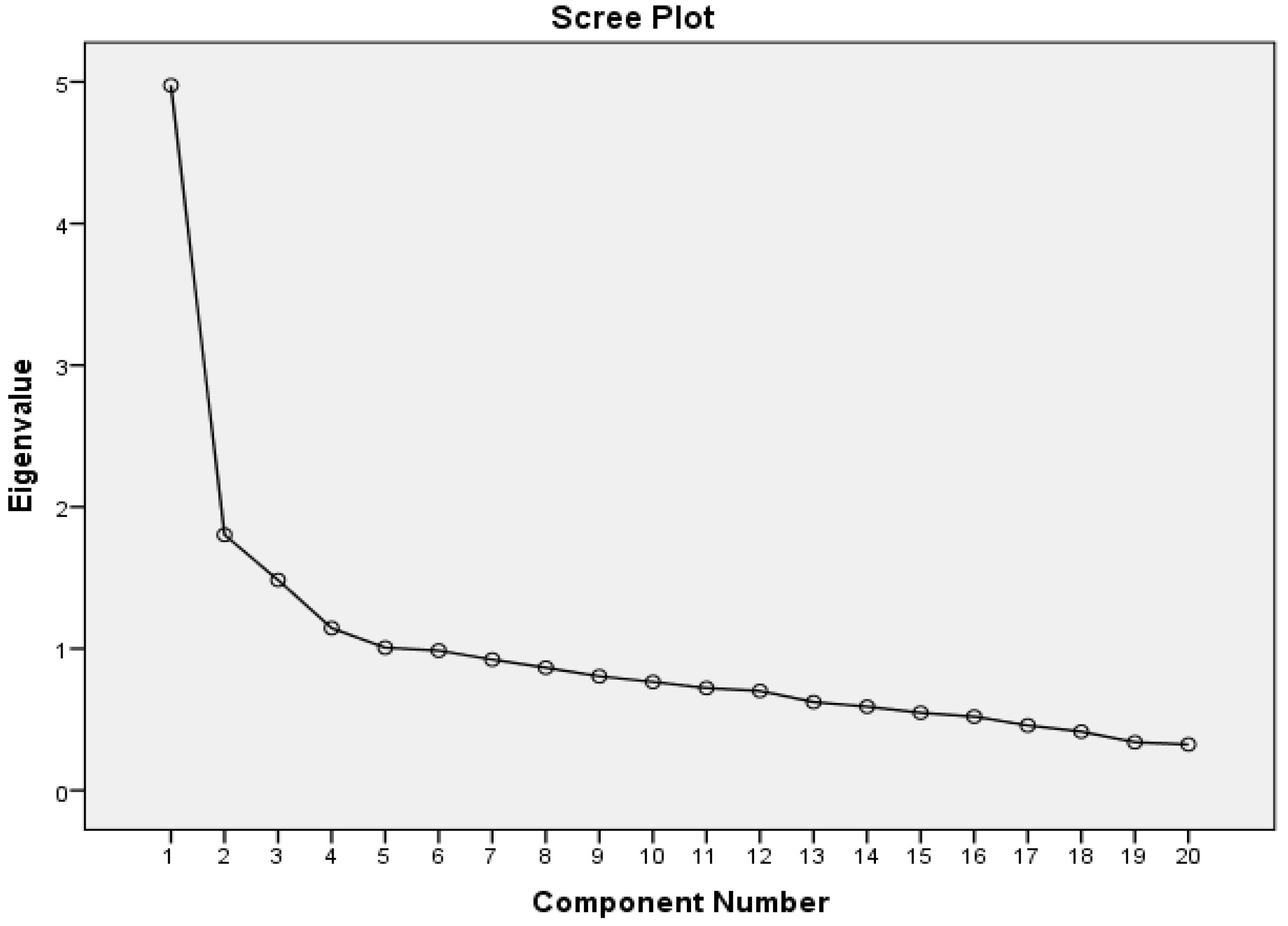

Pallant’s common variance table and Catell’s slope plot were used to determine the number of factors for this developed scale. When determining the number of factors on the slope plot, the point at which the graph’s regularity suddenly breaks down should be taken into account. Furthermore, factors with an eigenvalue of at least one should be considered in factor analysis [

41]. According to the analysis, five subscales with eigenvalues greater than 1 were identified. These subscales explain 52.074% of the total scale variance. The five-subscale structure is also supported by the scree plot results of our scale. As stated by Buyukozturk [

36], if an item has a factor loading below 0.30, it should not be included in the scale. In this study, the factor loadings of the scale, consisting of 20 items and 5 subscales, ranged from 0.41 to 0.80.

When developing a scale, EFA is used to verify the validity of the results obtained in CFA. In CFA, the structure of the scale is examined using X2/SD, RMSEA, AGFI, NFI, TLI, and CFI goodness-of-fit tests. An X2/SD value of five or less from the goodness-of-fit tests indicates a good fit for the tested model [

41,

42,

43]. The X2/SD value was found to be 1.655, indicating a good fit for the scale. Other goodness-of-fit indices for the scale were CFI = 0.927, AGFI = 0.910, and TLI = 0.913. These indices are within the acceptable range. The RMSEA value of the scale is 0.044, indicating an acceptable level of fit. The fit indices are derived from each other, evaluated together, and are closely related to each other [

43]. The five-factor structure of the scale was evaluated for fit after EFA, and this was confirmed.

In the reliability analysis of the scale, its internal consistency was examined. The most common method for examining the scale’s internal consistency is the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which assesses the agreement between the items [

37]. For a scale to demonstrate high reliability, its Cronbach’s alpha value must be between 0.70 and 1.00 [

38]. This developed scale has a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.79, indicating high reliability.

In this study, the five-factor solution was obtained within the set of analytic decisions made for factor extraction. Although multiple decision rules were considered (e.g., scree plot, theoretical coherence), choices regarding extraction/rotation and estimation/correlation type (e.g., ML–Pearson vs. WLSMV–polychoric) may affect the stability of the structure. Moreover, any data-driven model modifications (e.g., correlated residuals) can improve fit while increasing sample-specificity, thereby limiting generalizability. The single-region/convenience sampling frame further warrants caution when extrapolating findings across ages, genders, and contexts. Future work should include cross-validation on an independent sample, test–retest reliability over time, measurement invariance testing (configural/metric/scalar) across key subgroups, and consideration of alternative modeling (e.g., ESEM/bifactor) to more rigorously establish both the stability and generalizability of the five-factor structure.

Menstruation is a uniquely female phenomenon, and myths surrounding it exclude women from many sociocultural spheres. In many societies, even discussing menstruation is a taboo, hindering the development of social and cultural knowledge about the subject. During this period, women are considered unclean, face restrictions in their daily lives, are forbidden from praying, are seen as a source of shame, and are discouraged from physical activity [

7]. In many countries, girls are withdrawn from school because they perceive menstruation as the first step toward adulthood and the perception that women will marry. Furthermore, if there are insufficient pads and clean diapers, they cannot attend school that day [

44]. Lack of adequate hygiene supplies and the myth that bathing is not allowed make them vulnerable to infection. Furthermore, girls who remain unclean and whose menstrual blood is visible are stigmatized and isolated from school and life [

45]. The stress, recurring infections, and stigma they experience harm both their mental and reproductive health [

46]. Cultural taboos and myths contribute to the stigmatization of menstruation, restrictions on menstrual hygiene, and hinder women’s awareness and well-being [

46]. Menstrual myths negatively impact women of reproductive age physically, socially, psychologically, and spiritually, including the inability to attend school and work [

7]. It is essential to understand women’s attitudes toward menstrual myths to prevent reproductive health problems, integrate them into school and work, and prevent social isolation and stigma. This reliable scale facilitates healthcare professionals, educators, researchers, and policymakers to assess the attitudes of women of reproductive age toward menstrual myths. Further evidence can be obtained by repeating the study with different samples and can be used as a decisive tool in initiatives to prevent menstrual myths.

Our findings will contribute to both clinical practice and education as they provide a valid and reliable tool for measuring menstrual myths. Theoretically, the scale provides a framework for systematically examining the cultural and psychosocial dimensions of menstrual myths, while enabling comparative studies across different age groups and cultural contexts in future research.