Understanding the Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and HIV Risk Behaviors in U.S. Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Youth Risk Behavior Survey Findings (2005–2021)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

3.1. Eligibility Criteria

3.2. Selection Process

3.3. Data Extraction

3.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.5. Synthesis

4. Results

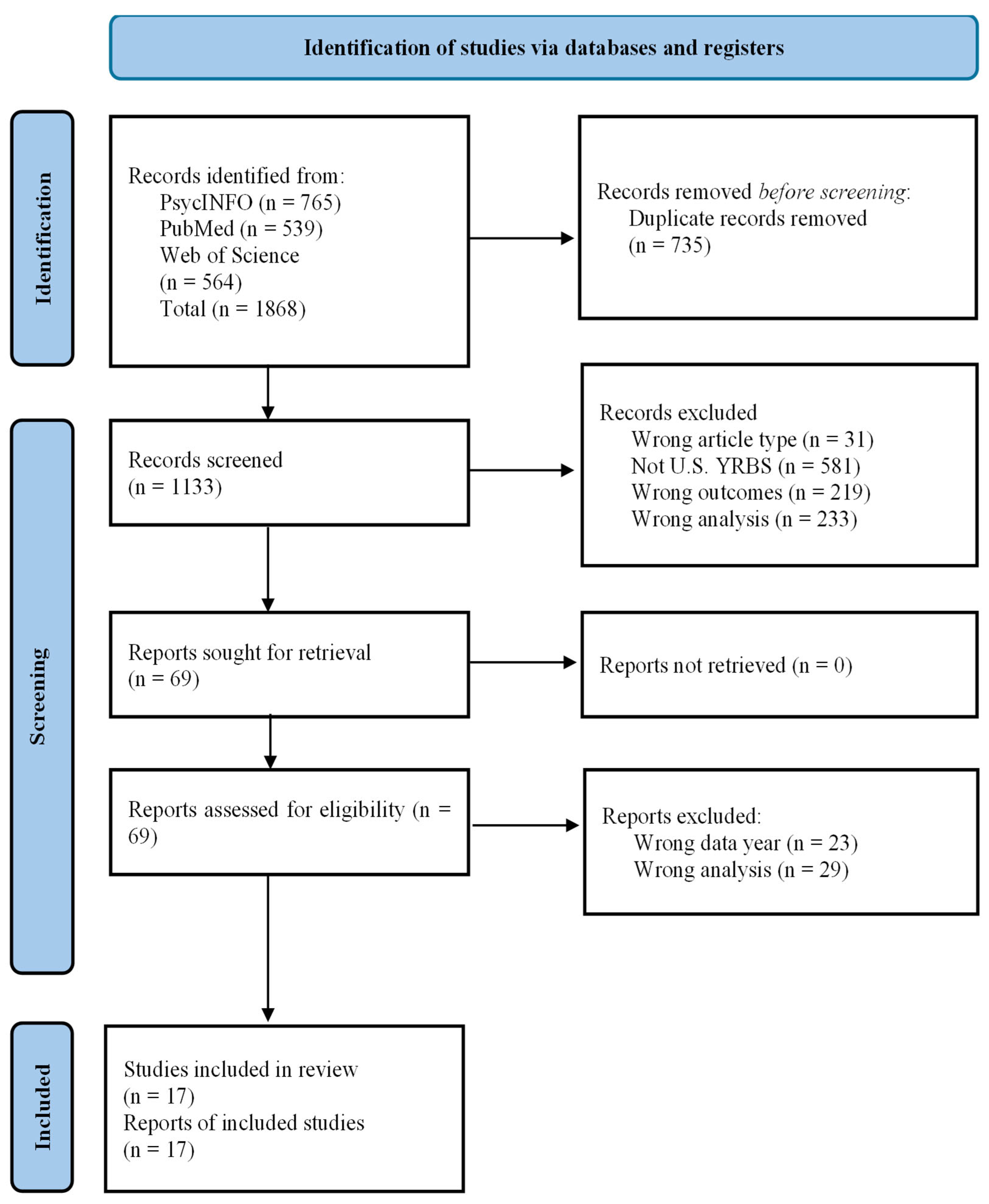

4.1. Study Selection

4.2. Result of Risk of Bias Assessment

4.3. Study Characteristics

4.4. Theoretical Frameworks

4.5. Measuring Risk Behaviors

4.6. Synthesis of Findings

4.6.1. Number of Sexual Partners and Alcohol-Related Behaviors

4.6.2. Condom Non-Use and Alcohol-Related Behaviors

4.6.3. HIV Testing and Alcohol-Related Behaviors

5. Discussion

5.1. Nuances in Findings and Methodological Considerations

5.2. Consistency and Gaps in Evidence

5.3. Theoretical Frameworks and Future Directions

5.4. Limitations of the Studies in This Review

5.5. Limitations of This Review

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Willoughby, T.; Heffer, T.; Good, M.; Magnacca, C. Is adolescence a time of heightened risk taking? An overview of types of risk-taking behaviors across age groups. Dev. Rev. 2021, 61, 100980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, N.D. Overview and methods for the youth risk behavior surveillance system—United States, 2023. MMWR Suppl. 2024, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott-Sheldon, L.A.; Carey, K.B.; Cunningham, K.; Johnson, B.T.; Carey, M.P.; Team, M.R. Alcohol use predicts sexual decision-making: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the experimental literature. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustanski, B.; Phillips, G.; Ryan, D.T.; Swann, G.; Kuhns, L.; Garofalo, R. Prospective effects of a syndemic on HIV and STI incidence and risk behaviors in a cohort of young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2017, 21, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janulis, P.; Jenness, S.M.; Risher, K.; Phillips, G., II; Mustanski, B.; Birkett, M. Substance use and variation in sexual partnership rates among young MSM and young transgender women: Disaggregating between and within-person associations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023, 252, 110968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, K.M.; Rutherford, C.; Miech, R. Historical trends in the grade of onset and sequence of cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use among adolescents from 1976–2016: Implications for “Gateway” patterns in adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 194, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Compton, W.M.; Blanco, C.; DuPont, R.L. National trends in substance use and use disorders among youth. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 747–754.e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.; Han, J.; Lee, C.; Yoon, M.; Jung, Y. Pathophysiological aspects of alcohol metabolism in the liver. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapert, S.F.; Eberson-Shumate, S. Alcohol and the adolescent brain: What we’ve learned and where the data are taking us. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2022, 42, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, T.B.; Monti, P.M.; Celio, M.A.; Pérez, A.E. Cognitive-emotional mechanisms of alcohol intoxication-involved HIV-risk behavior among men who have sex with men (MSM). Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 29, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palfai, T.P.; Luehring-Jones, P. How alcohol influences mechanisms of sexual risk behavior change: Contributions of alcohol challenge research to the development of HIV prevention interventions. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Group, P.-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustanski, B.; Van Wagenen, A.; Birkett, M.; Eyster, S.; Corliss, H.L. Identifying sexual orientation health disparities in adolescents: Analysis of pooled data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2005 and 2007. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, G.L.; Curtis, M.G.; Kelsey, S.W.; Floresca, Y.B.; Davoudpour, S.; Quiballo, K.; Beach, L.B. Changes to sexual identity response options in the youth risk behavior survey. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 506–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, J.; Brener, N.; Thornton, J.; Harris, W.; Bryan, L.; Shanklin, S.; Deputy, N.; Roberts, A.; Queen, B.; Chyen, D. Overview and methods for the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System–United States, 2019. Mortal. Morb. Wkly. Rep. Suppl. 2020, 69, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Study Quality Assessment Tools. 2021. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Prod. ESRC Methods Programme Version 2006, 1, b92. [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu, J.J. Overview and methods for the youth risk behavior surveillance system—United States, 2021. MMWR Suppl. 2023, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.E.; Brener, N.D.; Queen, B.; Hershey-Arista, M.; Harris, W.A.; Mpofu, J.J.; Underwood, J.M. Reliability of the 2021 national youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. Am. J. Health Promot. 2024, 38, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, L. Substance use and sexual risk behaviors among Mississippi public high school students. J. Miss. State Med. Assoc. 2012, 53, 323–328. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.Y.; Howe, C.J.; Zullo, A.R.; Marshall, B.D. Risk factors for self-report of not receiving an HIV test among adolescents in NYC with a history of sexual intercourse, 2013 YRBS. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2017, 12, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outlaw, A.Y.; Turner, B.; Marro, R.; Green-Jones, M.; Phillips, G., II. Student characteristics and substance use as predictors of self-reported HIV testing: The youth risk behavior survey (YRBS) 2013–2015. AIDS Care 2022, 34, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramisetty-Mikler, S.; Ebama, M.S. Alcohol/drug exposure, HIV-related sexual risk among urban American Indian and Alaska Native youth: Evidence from a national survey. J. Sch. Health 2011, 81, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavazos-Rehg, P.A.; Krauss, M.J.; Spitznagel, E.L.; Schootman, M.; Cottler, L.B.; Bierut, L.J. Number of sexual partners and associations with initiation and intensity of substance use. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi-Montecalvo, H.; Lilly, C.L.; Zullig, K.J.; Jarrett, T.; Cottrell, L.A.; Dino, G.A. A latent class analysis of the co-occurrence of risk behaviors among adolescents. Am. J. Health Behav. 2019, 43, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, Z.; Asim, M.; Javaid, I.; Rasheed, F.; Akhter, M.N. Analyzing risky behaviors among different minority and majority race in teenagers in the USA using latent classes. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1089434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, H.B.; Andrzejewski, J.; Johns, M.; Lowry, R.; Ashley, C. Does the association between substance use and sexual risk behaviors among high school students vary by sexual identity? Addict. Behav. 2019, 93, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, C.M.; Gilreath, T.D.; Hansen, N.B. A multiprocess latent class analysis of the co-occurrence of substance use and sexual risk behavior among adolescents. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2009, 70, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Kulkarni, N.; Rehmatullah, S. The type of substance use mediates the difference in the odds of sexual risk behaviors among adolescents of the United States. Cureus 2021, 13, e17264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, W.H.; Pierson, E.E. A mixture IRT analysis of risky youth behavior. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hingson, R.W.; Zha, W. Binge drinking above and below twice the adolescent thresholds and health-risk behaviors. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 42, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddon, N.; Olsen, E.O.M.; Carter, M.; Hatfield-Timajchy, K. Withdrawal as pregnancy prevention and associated risk factors among US high school students: Findings from the 2011 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Contraception 2016, 93, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahat, G.; Kelly, S. Factors affecting risk-taking behaviors among sexually active adolescents tested for HIV/STD. Public Health Nurs. 2023, 40, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scroggins, S.; Shacham, E. What a difference a drink makes: Determining associations between alcohol-use patterns and condom utilization among adolescents. Alcohol Alcohol. 2021, 56, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamotharan, S.; Grabowski, K.; Stefano, E.; Fields, S. An examination of sexual risk behaviors in adolescent substance users. Int. J. Sex. Health 2015, 27, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Kim, H.; Peltzer, J. Relationships among substance use, multiple sexual partners, and condomless sex: Differences between male and female US high school adolescents. J. Sch. Nurs. 2017, 33, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flay, B.R.; Petraitis, J. A new theory of health behavior with implications for preventive interventions. Adv. Med. Sociol. 1994, 4, 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessor, R. Problem-behavior theory, psychosocial development, and adolescent problem drinking. Br. J. Addict. 1987, 82, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, D.B. Stages and Pathways of Drug Involvement: Examining the Gateway Hypothesis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs NJ 1986, 1986, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, C.M.; Josephs, R.A. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widman, L.; Evans-Paulson, R.; Maheux, A.J.; McCrimmon, J.; Brasileiro, J.; Stout, C.D.; Lankster, A.; Choukas-Bradley, S. Identifying the strongest correlates of condom use among US adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2025, 179, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pound, P.; Campbell, R. Locating and applying sociological theories of risk-taking to develop public health interventions for adolescents. Health Sociol. Rev. 2015, 24, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brawner, B.M.; Kerr, J.; Castle, B.F.; Bannon, J.A.; Bonett, S.; Stevens, R.; James, R.; Bowleg, L. A systematic review of neighborhood-level influences on HIV vulnerability. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 874–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.L.; Strzyzykowski, T.; Lee, K.-S.; Chiaramonte, D.; Acevedo-Polakovich, I.; Spring, H.; Santiago-Rivera, O.; Boyer, C.B.; Ellen, J.M. Structural effects on HIV risk among youth: A multi-level analysis. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 3451–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, D.N.; Bradford, W.D. The effect of state-level sex education policies on youth sexual behaviors. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 2321–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, G.; McCuskey, D.; Ruprecht, M.M.; Curry, C.W.; Felt, D. Structural interventions for HIV prevention and care among US men who have sex with men: A systematic review of evidence, gaps, and future priorities. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 2907–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.L.; Michael White, C.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Kluger, J.; Coleman, C.I. Understanding heterogeneity in meta-analysis: The role of meta-regression. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2009, 63, 1426–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, C.M.; Ghali, W.A.; Saunders, L.D.; Brant, R.; Galbraith, D.; Faris, P.; Knudtson, M.L.; Investigators, A. Ordinal regression model and the linear regression model were superior to the logistic regression models. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2006, 59, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, V.; Meyers, E.M. Youth Research under the Microscope: A Conceptual Analysis of Youth Information Interaction Studies. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D.H. Social cognitive theory. In APA Educational Psychology Handbook; Harris, K.R., Graham, S., Urdan, T., McCormick, C.B., Sinatra, G.M., Sweller, J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schure, M.B.; Flay, B.R. The Theory of Triadic Influence. In Public Health Law Research. Theory and Methods; Wagenaar, A.C., Burris, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, USA, 2013; p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.-S.; Yang, Y. Relationship between alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviors among adolescents and young adults: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Public Health 2023, 68, 1605669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Moller, A.-B.; Adebayo, E.; Carvajal, L.; Ekman, C.; Fagan, L.; Ferguson, J.; Friedman, H.S.; Ba, M.G.; Hagell, A. Priority areas for adolescent health measurement. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 68, 888–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Berger, A.T.; Wells, B.E.; Cleland, C.M. Longitudinal associations between adolescent alcohol use and adulthood sexual risk behavior and sexually transmitted infection in the United States: Assessment of differences by race. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexual Health Education. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthy-youth/what-works-in-schools/sexual-health-education.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ciccarese, G.; Drago, F.; Herzum, A.; Rebora, A.; Cogorno, L.; Zangrillo, F.; Parodi, A. Knowledge of sexually transmitted infections and risky behaviors among undergraduate students in Tirana, Albania: Comparison with Italian students. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2020, 61, E3. [Google Scholar]

| Author (Year) | Study Aims and Theoretical Frameworks | YRBS Datasets and Target Population | Sample Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadi-Montecalvo et al. (2019) [26] | Examine the co-occurrence of multiple health-risk behaviors to determine whether there are any differences in the pattern of co-occurrence by sex. Theories: Problem behavior theory. | Level: National Year(s): 2013 Population: High school students; analyzed female and male subgroups | Criteria: None specified Size: 13,571 (6950 male, 6621 female) Age range: <12–18 |

| Aslam et al. (2023) [27] | Ascertain inconsistencies in the trend of co-occurrence among different minority and majority races by sex of teenage health risk behavior patterns such as smoking, behaviors contributing to deliberate and unintentional injuries, risky sexual behavior, and sedentary lifestyle. Theories: Problem behavior theory. | Level: National Year(s): 2013 Population: High school students; analyzed female and male subgroups | Criteria: None specified Size: 13,583 (male and female subsample sizes NR) Age range: <12–18 |

| Cavazos-Rehg et al. (2011) [25] | Examine how age of substance use initiation and variations in use (i.e., experimental/new user, moderate, heavy versus non-user) are associated with increased number of sexual partners. Theories: None. | Level: National Years: 1999–2007 (pooled) Population: High school seniors; analyzed female and male subgroups | Criteria: included 12th graders aged 17 and older; excluded racial/ethnic groups other than White, African American, and Hispanic; excluded those with missing data Size: 11,268 Age range: ≥17 |

| Clayton et al. (2019) [28] | Explore potential differences in associations between sexual risk taking and substance use by sexual identity. Theories: Minority Stress theory, permissive norms. | Level: National Year(s): 2015 Population: High school students; compared lesbian, gay, and bisexual and heterosexual students | Criteria: Excluded respondents who were “not sure” of their sexual identity Size: 14,200 (12,954 heterosexual; 1246 lesbian, gay, and bisexual) Age range: 12–19 |

| Connell et al. (2009) [29] | Assess the co-occurrence of patterns of adolescent substance use and sexual behavior and test for potential moderating effects of gender. Theories: Gateway hypothesis. | Level: National Year(s): 2005 Population: High school students; analyzed female and male subgroups | Criteria: None specified Size: 13,953 Age range: ≤14–≥18 |

| Desai et al. (2021) [30] | Identify the prevalence of sexual risk behaviors in U.S. high school students and study the difference in the odds of sexual risk behaviors for various substances. Theories: None. | Level: National Year(s): 2019 Population: High school students | Criteria: Excluded respondents with missing data for age, sex, race, grade, and/or substance use Size: 11,191 Age range: ≤14–≥18 |

| Finch & Pierson (2011) [31] | Identify typologies of adolescents based on their propensity for engaging in sexually and substance use risky behaviors. Theories: None. | Level: National Year(s): 2009 Population: High school students | Criteria: None specified Size: 16,410 Age range = NR, M = 16.03, SD = 1.23 |

| Gao et al. (2017) [22] | Estimate the prevalence of and identify risk factors for not receiving an HIV test among New York City adolescents with a history of sexual intercourse. Theories: None. | Level: Large urban school district (New York City) Year(s): 2013 Population: Sexually experienced New York City high school students | Criteria: Included respondents who replied “yes” or “no” to ever receiving HIV testing and reported lifetime sexual intercourse; excluded respondents with missing data for relevant characteristics and risk factors Size: 1199 Age range: ≤14–≥18 |

| Hingson & Zha (2018) [32] | Explore whether adolescent binge drinking at ≥ twice versus < twice the age-/gender-specific thresholds versus non-binge drinking heightens associations of drinking with health-risk behaviors. Theories: Problem behavior theory. | Level: National Year(s): 2015 Population: High school students | Criteria: Excluded respondents younger than 14 Size: 13,191 Age range: 14–≥18 |

| Liddon et al. (2016) [33] | Describe the prevalence of withdrawal as their primary method of pregnancy prevention at last sexual intercourse among sexually active US high school students and associations with sexual risk and substance use. Theories: None. | Level: National Year(s): 2011 Population: Sexually active high school students; analyzed female and male subgroups | Criteria: Included respondents who reported current sexual activity (i.e., past three months); excluded respondents who answered “I did not have sexual intercourse” to either of two contraceptive questions Size: 4793 Age range: NR |

| Mahat & Kelly (2023) [34] | Identify potential contributors to high-risk sexual behaviors among sexually active adolescents who were tested for HIV and STDs compared to those who did not test for HIV and STDs. Theories: None. | Level: National Year(s) 2019 Population: Sexually active high school students; compared those who had vs. had not been tested for HIV and STDs | Criteria: Included respondents who reported current sexual activity Size: 3226 (1010 HIV tested, 2216 not HIV tested; 1353 STD tested, 1873 not HIV tested) Age range = NR, M = 16.4, SD = 1.2 |

| McGuire et al. (2012) [21] | Describe the patterns of substance use, sexual risk behaviors, and mental health problems and examine the relationship between substance use and sexual risk behaviors. Theories: None. | Level: State (Mississippi) Year(s): 2009 Population: Public high school students in Mississippi | Criteria: Excluded respondents who did not report their race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic White or non-Hispanic Black Size: 1789 Age range: ≤14–≥18 |

| Outlaw et al. (2022) [23] | Examine high school student characteristics and substance use in relation to self-reported HIV testing. Theories: None. | Level: All states and large urban school districts (pooled) Year(s): 2013–2015 (pooled) Population: High school students; analyzed female and male subgroups | Criteria: Excluded respondents with missing data for race/ethnicity, sex, age, sexual behavior, and/or HIV testing Size: 541,410 Age range: ≤14–≥18 |

| Ramisetty-Mikler & Ebama (2011) [24] | Investigate the patterns of alcohol, other drug use, and sexual risk behavior among homogenous and biracial American Indian and Alaska Native youth; analyze the association between alcohol/drug use and sexual risk. Theories: None. | Level: National Year(s): 2005–2007 (pooled) Population: American Indian and Alaska Native high school students; analyzed female and male subgroups | Criteria: Included respondents who identified as American Indian and Alaska Native, either alone or with White, African American, or Hispanic race/ethnicity; excluded those who identified as American Indian and Alaska Native and multiple other races Size: 1178 Age range: ≤14–≥17 |

| Scroggins & Shacham (2021) [35] | Compare the associations between alcohol-use patterns and condom utilization among US adolescents to more accurately determine risk of STIs. Theories: Social cognitive theory, alcohol myopia models, disinhibition theory. | Level: National Year(s): 2017 Population: Sexually active high school students | Criteria: Limited to students who reported ≥1 sexual partner in the past three months Size: 3732 Age range: NR |

| Thamotharan et al. (2015) [36] | Examine the relationship between substance use and high-risk sexual behavior. Theories: Problem behavior theory. | Level: National Year(s): 2011 Population: High school students | Criteria: None specified Size: 15,425 Age range: ≤12–≥18 |

| Zhao et al. (2017) [37] | Provide information about the differences in condomless sex between male and female adolescents, including multiple sex partners and substance use. None: Triadic influence. | Level: National Year(s): 2011 Population: Sexually active high school students; analyzed female and male subgroups | Criteria: Excluded respondents who did not have sexual intercourse during the previous three months and/or did not report their gender, grade, or condom use at last sexual intercourse. Size: 4968 Age range: ≤12–≥18 |

| Authors (Year) | Alcohol and HIV Risk Variables | Definition of Risk Behaviors and Analysis Methods | Relevant Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadi-Montecalvo et al. (2019) [26] | Alcohol: Alcohol use in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days); binge drinking (≥5 drinks in a row) in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days) HIV: Lifetime sexual partners (<4 vs. ≥4 people); condom use during last sexual intercourse (yes, no) | Definition: Examined 40 “health risk behaviors” in total; analyzed all as binary variables Analysis: Latent class analysis including 40 health risk behaviors, stratified by sex | Among male, female, and all respondents, the class with high levels of alcohol use had a greater probability of ≥ 4 lifetime sexual partners and condom non-use compared to the class with a low prevalence of all examined behaviors. |

| Aslam et al. (2023) [27] | Alcohol: Alcohol use in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days); binge drinking (≥5 drinks in a row) in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days) HIV: Lifetime sexual partners (<4 vs. ≥4 people); condom use during last sexual intercourse (yes, no) | Definition: Examined 40 “health risk behaviors” in total; analyzed all as binary variables Analysis: Latent class analysis including 40 health risk behaviors, stratified by sex | For both male and female respondents, the analysis identified a class characterized by a high co-occurrence of alcohol with multiple sexual partners and condom non-use. |

| Cavazos-Rehg et al. (2011) [25] | Alcohol: Age at first drink (≤12, 13–14, ≥15); alcohol use intensity (non-users, experimental/new users [1–9 lifetime uses], moderate users [10–99 lifetime uses], heavy users [100+ lifetime uses]) HIV: Lifetime sexual partners (0, 1, 2 … 5, ≥6). | Definition: Used categories of increasing risk (younger age at first drink, heavier alcohol use, more lifetime sexual partners) Analysis: Multinomial multivariable logistic regression analyses with alcohol use variables as predictors of HIV risk behaviors, stratified by sex | For both female and male groups, greater intensity of alcohol use was associated with greater odds of a higher number of sexual partners, following a stepwise pattern. Age at first drink of alcohol had little effect on number of sexual partners. |

| Clayton et al. (2019) [28] | Alcohol: Alcohol use in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days); binge drinking (≥5 drinks in a row) in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days) HIV: Lifetime sexual partners (<4 vs. ≥4 people); Condom use at last sexual intercourse (yes vs. no) | Definition: Described variables as “substance use and risky sexual behaviors”; analyzed all as binary variables Analysis: Logistic regression models with alcohol use variables as predictors of HIV risk behaviors, stratified by sexual identity | Among both heterosexual and lesbian, gay, and bisexual groups, alcohol use and binge drinking were both associated with having ≥ 4 lifetime sexual partners. Alcohol use was not associated with condom non-use for either group. Binge drinking correlated with condom non-use in heterosexuals. |

| Connell et al. (2009) [29] | Alcohol: Alcohol use in past 30 days (no history, no past-month use, infrequent [1–5 days], frequent [≥6 days]); binge drinking in past 30 days (no history, no past-month use, infrequent [1–5 days], frequent [≥6 days]) HIV: Sexual partners in past 3 months and lifetime (0, 1, 2…5, ≥6); condom use during last sexual intercourse (no history, yes, no); history of HIV testing (yes, no, don’t know) | Definition: Described variables as “substance use and sexual risk behaviors”; analyzed all as ordinal variables Analysis: Latent class analysis, with multinomial logistic regression to examine substance use class as predictor of sexual behavior class; also tested interaction effects between gender and substance use on sexual behavior. | For the class characterized by alcohol use alone versus nonusers, odds of belonging to the class with multiple lifetime but not recent sexual partners were significantly greater, and odds of being in the class with multiple lifetime and recent sexual partners were also significantly greater. These patterns were stronger for female versus male respondents. |

| Desai et al. (2021) [30] | Alcohol: Lifetime alcohol use (yes, no; coded from question about age of initiation) HIV: Lifetime sexual partners (<4 vs. ≥4 people); condom use at last sexual intercourse (yes, no) | Definition: Described “substance use and sexual risk behaviors”; binary defined “sexual risk behaviors” as reporting both ≥ 4 lifetime sexual partners and condom non-use Analysis: Multivariable logistic regression analysis to examine various substance use outcomes as predictors of odds of sexual risk behaviors | After adjusting for age, sex, race, grade and other substance use, the odds of sexual risk behaviors were significantly higher for participants who had ever used alcohol. |

| Finch & Pierson (2011) [31] | Alcohol: Alcohol use in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days) HIV: Lifetime sexual partners (<4 vs. ≥4 people) | Described all variables as “risky sexual and substance use behaviors”; analyzed as binary Mixed item response theory analysis; multivariate analysis of variance and discriminant analysis comparing the latent classes on the sums of risky sexual and substance use behaviors engaged in. | The class with the greatest prevalence of risky sexual behaviors (Class 1) had a greater prevalence of alcohol use compared to other classes. Other classes were defined by prevalent alcohol use but not sexual risk behaviors (Class 2), prevalent sexual risk behaviors but not alcohol use (Class 3), and a low prevalence of all risk behaviors (Class 4). |

| Gao et al. (2017) [22] | Alcohol: Binge drinking (≥5 drinks in a row) in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days) HIV: History of HIV testing (yes, no) | Definition: Considered binge drinking and other substance use as risk factors; analyzed as binary Analysis: Modified Poisson regression to examine alcohol and other substance use in relation to HIV testing. | No significant association was found between binge drinking and HIV testing. |

| Hingson & Zha (2018) [32] | Alcohol: Binge drinking in past 30 days (abstained from alcohol, drank but did not binge, binged < twice the age- and sex-specific threshold, or binged ≥ twice the threshold). HIV: Sexual partners in past 3 months (0, 1, 2, ≥3); condom use at last sexual intercourse (yes, no) | Definition: Described all variables as “health risk behaviors”; analyzed alcohol variables and number of sexual partners as ordinal Analysis: Logistic regression analyses with pairwise comparisons of number of sexual partners by different drinking levels | Compared to non-drinkers, those binging ≥ twice thresholds had significantly greater odds of multiple sexual partners in the past 3 months and significantly lower odds of condom use. Those binging ≥ twice thresholds versus < twice thresholds and non-binge drinkers were significantly more likely to have multiple sexual partners. The same held for binging at < twice thresholds compared to non-binge drinkers. |

| Liddon et al. (2016) [33] | Alcohol: Alcohol use in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days); binge drinking (≥5 drinks in a row) in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days) HIV: Sexual partners in past 3 months (<2 vs. ≥2 people) (only as a predictor of condom use, not a separate outcome); condom use (yes, no) and other contraceptive use | Definition: Described variables as “substance use and sexual risk” behaviors; analyzed alcohol measures as binary and condom/contraceptive use as ordinal (no method, condoms alone, highly effective contraceptive method) Analysis: Chi-square analyses; bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses with alcohol variables and multiple sexual partners as predictors of condom and contraceptive use. | The prevalence of alcohol use and binge drinking was highest among students who did not use condoms or other contraceptives, lower among those who used condoms alone, and lowest among students who used a highly effective method. This pattern held among female but not male students. |

| Mahat & Kelly (2023) [34] | Alcohol: Alcohol use in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days) HIV: Sexual partners (did not specify lifetime or recent; <4 vs. ≥4 people); condom use at last intercourse (yes, no); ever being tested for HIV (yes, no) | Definition: Considered all variables as “risk-taking behaviors”; analyzed all variables as binary Analysis: Chi-square analyses to test differences between testing status groups; logistic regression to examine alcohol use in relation to sexual risk behaviors | Those who were never tested for HIV were more likely to use condoms and less likely to have multiple sexual partners than those tested for HIV, with a similar pattern for STD testing. No significant differences were found by HIV or STD testing status for alcohol use. Among those tested for HIV, alcohol use did not correlate with condom use or multiple sexual partners. Among those tested for STDs, alcohol use correlated with multiple sexual partners but not condom use. |

| McGuire et al. (2012) [21] | Alcohol: Lifetime alcohol use (≥1 vs. 0 days); binge drinking (≥5 drinks in a row) in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days) HIV: Lifetime sexual partners (<4 vs. ≥4 people); condom use at last intercourse (yes, no) | Definition: Described variables as “substance use and sexual risk behaviors”; analyzed all variables as binary Analysis: Chi-squared test to examine sex differences in risk behaviors; bivariate and multiple logistic regression models to examine alcohol variables in relation to sexual risk behaviors | In multivariate analyses, ever drinking alcohol and binge drinking were both positively associated with having four or more lifetime sexual partners. Alcohol use and binge drinking were not associated with condom use. |

| Outlaw et al. (2022) [23] | Alcohol: Lifetime alcohol use (≥1 vs. 0 days); age of first drink of alcohol (<13 vs. ≥13 years); binge drinking (≥5 drinks in a row) in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days) HIV: ever being tested for HIV (yes, no) | Definition: Described all variables as behaviors associated with risk for HIV; analyzed all variables as binary Analysis: Sex-stratified, stepwise multivariable logistic models to examine associations of student characteristics and substance use with odds of ever having received a HIV test | When controlling for student characteristics and alcohol use, binge drinking correlated with increased odds of HIV testing for female students only, while alcohol use before age 13 correlated with increased odds of testing for male students only. After controlling for drug use, these relationships were not significant. |

| Ramisetty-Mikler & Ebama (2011) [24] | Alcohol: Lifetime alcohol use (≥1 vs. 0 days); age at first drink (≤10, 11–12, 13–14, and ≥15 years); episodic drinking, based on frequency and amount of drinking in past 30 days (never drank, drank ≥ 3 days but no binge drinking, binge drank ≥ 1 days) HIV: Lifetime and past 3-month sexual partners (never had sex, 1 partner, ≥2 partners); condom use at last intercourse (yes, no) | Definition: Referred to “alcohol/drug use predictors of sexual risk taking”; examined alcohol use as binary and other multilevel variables as ordinal Analysis: Sex-specific bivariate and multivariate analyses to identify associations between alcohol and other drug use and sexual behaviors; individual logistic regression and multinomial models to examine episodic drinking and age of initiation of alcohol and drugs in relation to sexual behaviors | At the bivariate level, episodic but not non-episodic drinkers were more likely to have four or more lifetime sexual partners and more than one recent sexual partner compared to non-drinkers, among males and females. Condom use was higher for non-episodic drinkers, and lower for episodic drinkers, than non-drinkers, among males only. Controlling for demographics, episodic but not non-episodic drinkers were significantly more likely to have two or more lifetime sexual partners than non-drinkers. Drinking status was not correlated with condom use. Age at first drink was not correlated with condom use or multiple sexual partners. |

| Scroggins & Shacham (2021) [35] | Alcohol: Alcohol consumption pattern, based on frequency and amount of drinking in past 30 days (non-drinker, binge drank ≥ 1 days, drank with no binge drinking) HIV: Condom use at last intercourse (yes, no) | Definition: Described variables as “alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors”; analyzed alcohol use pattern as ordinal Analysis: Chi-square tests for bivariate associations between alcohol use pattern and condom use; univariate and multivariate logistic regressions to estimate odds of condom non-use based on alcohol-use pattern | Alcohol use was significantly associated with condom use in each analysis. In the adjusted model, those who drank with no binge drinking and those who reported no recent alcohol use were more likely to report condom use than those with at least one binge-drinking episode. |

| Thamotharan et al. (2015) [36] | Alcohol: Lifetime alcohol use (0, 1 or 2, 3–9, 10–19, 20–39, 40 or more days); alcohol use in past 30 days (0, 1 or 2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–19, 20–29, all 30 days); age of initiation for alcohol use (never, ≤11, 12, 13 … ≥17) HIV: Lifetime and past 3-month sexual partners (never, 1, 2… ≥6); condom use at last sexual intercourse (yes, no); ever being tested for HIV (yes, no). | Definition: Described variables as “substance use and sexual risk behaviors”; analyzed all multilevel variables as ordinal Analysis: Logistic and linear regression analyses to determine the relationship between alcohol use behaviors and sexual risk behaviors, including age and race/ethnicity as covariates | Greater lifetime and recent alcohol consumption both significantly correlated with more lifetime and recent sexual partners, not using a condom during recent sexual intercourse, and having ever been tested for HIV. Age of first alcohol use was not associated with number of lifetime or recent sexual partners or condom use. |

| Zhao et al. (2017) [37] | Alcohol: Alcohol use in past 30 days (≥1 vs. 0 days) HIV: Condom use at last intercourse (yes, no) | Definition: Referred to “alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors”; examined alcohol use as binary Analysis: Binary logistic regression models stratified by sex to examine condom use in relation to alcohol use and other variables; independent t and chi-square tests) to compare male and female respondents. | Recent alcohol drinking was not significantly associated with condomless sex for either males or females. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davoudpour, S.; Kerr, M.; Phillips II, G.L. Understanding the Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and HIV Risk Behaviors in U.S. Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Youth Risk Behavior Survey Findings (2005–2021). Healthcare 2025, 13, 2370. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182370

Davoudpour S, Kerr M, Phillips II GL. Understanding the Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and HIV Risk Behaviors in U.S. Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Youth Risk Behavior Survey Findings (2005–2021). Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2370. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182370

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavoudpour, Shahin, Madeline Kerr, and Gregory L. Phillips II. 2025. "Understanding the Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and HIV Risk Behaviors in U.S. Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Youth Risk Behavior Survey Findings (2005–2021)" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2370. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182370

APA StyleDavoudpour, S., Kerr, M., & Phillips II, G. L. (2025). Understanding the Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and HIV Risk Behaviors in U.S. Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Youth Risk Behavior Survey Findings (2005–2021). Healthcare, 13(18), 2370. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182370