The Impact of Toxic Leadership on Nurse Retention: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Toxic Leadership and the Toxic Leader

1.2. Nursing Staff Retention

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim of the Study

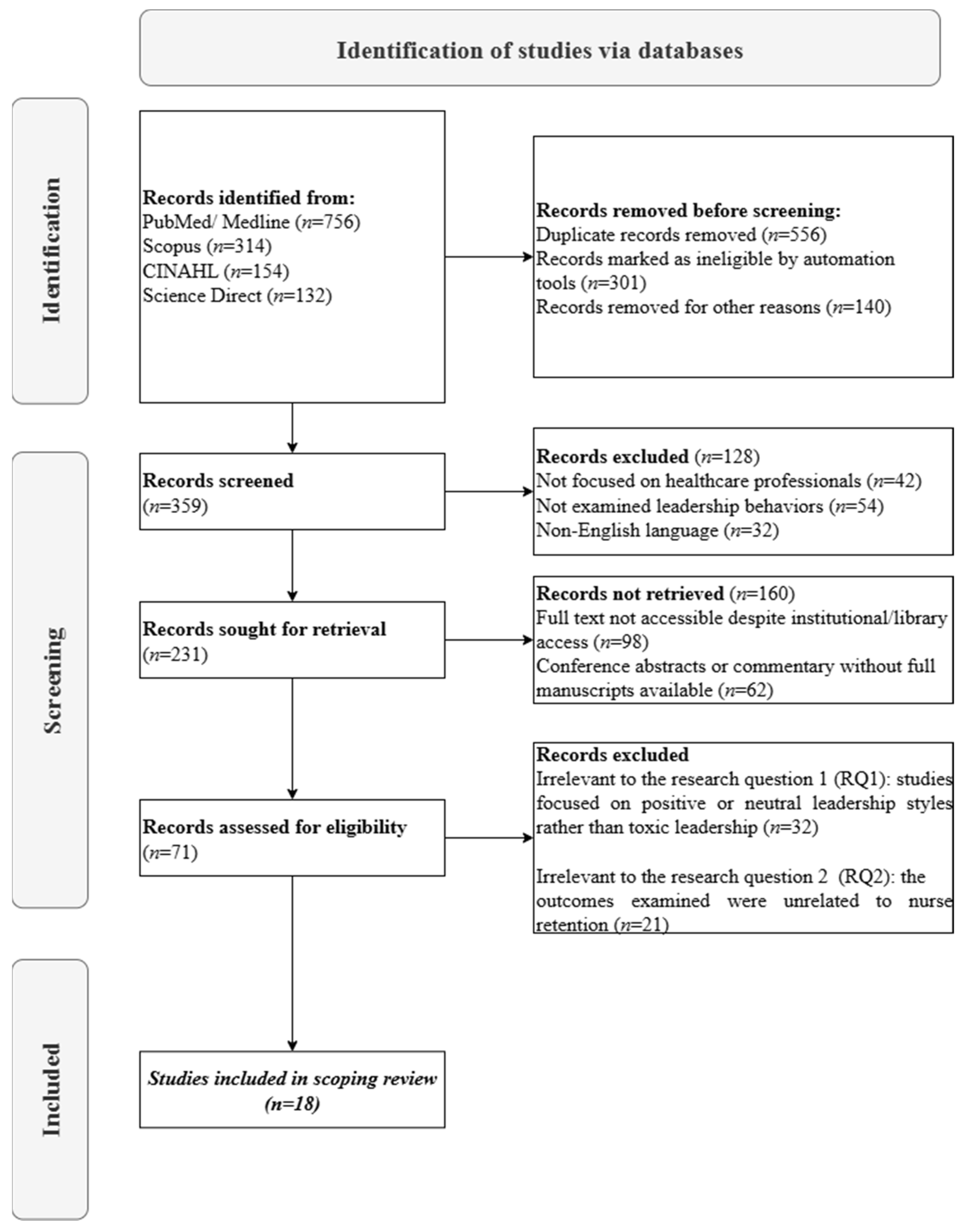

2.2. Design

2.3. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Charting the Data

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Consultation

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Perceptions of Toxic Leadership Key Dimensions

3.3. Toxic Leadership and Its Impact on Staff Retention

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Strengths

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| A/A | Author(s), Year | Country | Aim | Data Sample | Study Design | Data Collection Method | Data Analysis Method | Finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Labrague et al., 2020 [52] | Philippines | This study examined the influence of toxic and transformational leadership practices on nurses’ job satisfaction, psychological distress, absenteeism, and intent to leave the organization or the nursing profession. | 770 | Cross-sectional study | Toxic Leadership Behaviors of Nurse Managers Scale, Global Transformational Leadership, Job Satisfaction Index, Perceived Stress Scale, Two single-item measures developed by O’Driscoll and Beehr, Absenteeism was assessed using a researcher-designed single item question | SPSS Version 22.0 | Toxic leadership increased distress and absenteeism; transformational leadership improved job satisfaction. |

| 2. | Hossny et al., 2023 [51] | Egypt | This study was designed to assess nurses’ perception of the effects of organizational climate and toxic leadership behaviors on their intention to stay and the differences in these domains between the two hospitals studied | 250 | descriptive comparative study | the organizational climate questionnaire (42 items categorized into nine domains), the toxic leadership scale (30 items categorized into five domains), and the Chinese version of the intent-to-stay scale. | IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22.0, Microsoft Excel, GraphPad Prism 5 | Positive organizational climate and supportive systems increased nurses’ intention to stay. |

| 3. | Ofei, 2022 [53] | Ghana | This study aimed at assessing the nature and effect of toxic leadership of nurse managers on the perceived job satisfaction and productivity of the nursing workforce. | 943 | Cross-sectional descriptive study | Toxic Leadership Behaviors of Nurse Managers’ Scale, Perceived Productivity Questionnaire, and the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ-short version) | SPSS software version 26 | Toxic leadership reduced nurses’ job satisfaction and productivity. |

| 4. | Ramdan and Eid., 2020 [54] | Egypt | This study envisioned to compare toxic leadership among intensive care nursing staff at Tanta University Hospital and El Menshawy hospital and assess its relation to their conflict management style used and organizational commitment at the two hospitals. | 544 | Descriptive, comparative, cross-sectional study | Toxic Leadership Assessment Scale, Conflict Management Styles, Assessment Scale, Organizational Commitment Assessment Scale | IBM SPSS software package version 20.0. | Toxic leadership reduced organizational commitment and influenced conflict management styles. |

| 5. | Xueqin Guo et al., 2022 [47] | China | The aim of this study is to explore the perceptions of Chinese registered nurses on toxic leadership behaviors of nurse managers and to determine its type, cause and response measures | 12 | Phenomenological qualitative study | semi-structured in-depth interviews | Colaizzi seven-step analysis method | Nurses working with a transformational leader report higher job contentment and lower intent to leave the nursing profession. Nurses who work for a manager with toxic leadership behaviors demonstrated lower job contentment, higher stress levels, frequent absenteeism and higher intent to leave the nursing profession. |

| 6. | Siyal et al., 2021 [55] | China | The aim of this study is to develop and empirically test a mediation model to examine the indirect impact of abusive supervision on employee performance. | 430 | Empirical, experimental study | The 10-item scale version of the 15-item scale by Aryee et al., [92] developed by Tepper [93], 4-item scale validated by Amabile et al. [94], general satisfaction 5-item measure by Hackman and Oldham [95], the 4-item scale to measure employee performance developed by Liden et al. [96]. | Model development and empirical testing | Abusive supervision reduced employee performance. |

| 7. | Durrah et al., 2024 [48] | France | The current study aims to examine how toxic management styles can lead to both psychological and physical withdrawal of employees in the healthcare sector | 413 | Quantitative study | Self-developed questionnaire | SmartPLS 3.3.9 | Toxic leadership increased both psychological and physical withdrawal behaviors |

| 8. | Trépanier et al., 2019 [56] | Canada | The aim of this paper is to investigate the psychological and motivational processes involved in the relationship between two forms of destructive leadership (tyrannical and laissez-faire) and employee health (burnout, affective commitment and job performance) | 399 | Cross-sectional study | The Destructive Leadership Scale, The French version of the Psychological Need Thwarting Scale, The Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale, The Maslach Burnout Inventory General Survey, The occupational commitment questionnaire A self-reported scale consisting of 4 items adapted from the in-role performance subscale of the organizational citizenship behavior scale | Structural equation modeling analysis. | Tyrannical leadership frustrates autonomy, competence, and relatedness, leading to burnout and lower performance. |

| 9. | Erschens et al., 2022 [57] | Germany | The aim of this study is to investigate the association of general well-being and different leadership styles among employees in a German tertiary hospital. | 1137 | Cross-sectional study | Module A and D of the standardized Questionnaire on Integrative Leadership, the five-item World Health Organization well-being index | IBM SPSS version 25 | Transformational and transactional leadership styles are associated with higher well-being scores among hospital employees, while laissez-faire and destructive leadership styles are associated with lower scores across all professional groups. |

| 10. | Low et al., 2019 [58] | Malaysia | The aims of this research are to address the two fundamental research questions: (1) What are the antecedents that lead to counterproductive work behavior (CWB) of nurses in public hospitals? (2) How effective are the moderating roles of power distance orientation (a cultural factor) and locus of control (an individual factor) in impacting CWB? | 337 | Quantitative study | Tepper’s [93] 15-item abusive supervision Measure, Colquitt’s [97] 20-item scale 24-item measure adapted from Mitchell and Ambrose [98] and Bennett and Robinson‘s [99], six-item scale developed by Dorfman and Howell, [100] and Farh, Hackett and Liang’s [101] 16-item Work Locus of Control Scale | structural equation modeling | Abusive supervision leads to counterproductive work behavior in nurses |

| 11. | Shipl et al., 2022 [59] | Egypt | This study aimed to investigate the relationship between toxic leadership and nurse followership effectiveness | 343 | Cross-sectional study | The Toxic Leadership Scale and the Followership Styles Questionnaire | IBM SPSS, version 25 | Toxic leadership negatively correlated with nurse followership effectiveness |

| 12. | Berma et al., 2021 [60] | Egypt | This study aimed to investigate the relationship between workplace toxicity, organizational silence and thriving among nurses. | 235 | descriptive correlational research | Toxic Workplace Environment Questionnaire, Organizational Silence Scale, Thriving at Work Scale | SPSS version 22.0 | Workplace toxicity leads to increased organizational silence, reducing thriving among nurses and potentially leading to staff resignation |

| 13. | Bakkal et al., 2019 [49] | Turkey | The aim of this study is to investigate the effects of the toxic leadership of healthcare employees on the turnover intention and the mediating effects of job satisfaction | 658 | cross-sectional descriptive study | The Toxic Leadership Scale, the Minnesota Job Satisfaction Questionnaire, a turnover intention scale by Rosin & Korabik [102] | Confirmatory Factor Analysis, Structural Equation Model SPSS 24.0 and AMOS 24.0 | Toxic leadership negatively impacts job satisfaction, which in turn increases turnover intention among healthcare personnel |

| 14. | Budak & Erdal, 2022 [61] | Turkey | The aim of this study is to investigate the mediating effect of burnout syndrome on toxic leadership and job satisfaction | 412 | cross-sectional study | Toxic Leadership Scale, Burnout Scale, Job Satisfaction Scale | Structural Model Analysis | Toxic leadership negatively affects job satisfaction and increases burnout syndrome |

| 15. | Mrayyan, 2025 [62] | Jordan | The aim of this research is to investigate nursing leaders’ toxic leadership, nurses’ workplace satisfaction, job engagement, and turnover intention in Jordan and whether toxic leadership and sample characteristics predict nurses’ work- place satisfaction, job engagement, and turnover intention. | 384 | cross-sectional study | Toxic Leadership Scale, Nursing Workplace Satisfaction Scale, Job Engagement Scale, Turnover Intention Scale | Online survey, SPSS program version 25 | Toxic leadership results in low job satisfaction, stress and emotional exhaustion, and, in turn, decreased quality of nursing care |

| 16. | Labrague, 2024 [63] | Philippines | The aim of this study is to examine the mediating effects of work-family conflict on the relationship between toxic leadership behaviors of nurse managers and psychological distress and work satisfaction among emergency nurses. | 283 | cross-sectional study | Toxic Leadership Behaviors of Nurse Managers Scale, Work-Family Conflict Scale, Job Stress Scale and the Job Satisfaction Index | Mediation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS Macro with Model 4. | Toxic leadership reduced work satisfaction and increased psychological distress |

| 17. | Farghaly Abdelaliem & Abou Zeid, 2023 [64] | Egypt | The aim of this study is to assess toxic leadership and organizational performance among nurses of a University Hospital, and explore the mediating effect of nurses ‘silence | 750 | cross-sectional study | The toxic leadership scale, the organizational performance questionnaire | structured equation modeling | Toxic leadership had a significant negative relationship with organizational performance and the nurses’ silence |

| 18. | Ofei et al., 2023 [50] | Ghana | The aim of this study is to investigate the mediating role of job satisfaction on toxic leadership and turnover intentions of nurses | 943 | cross-sectional study | The Turnover Intention, Minnesota Satisfaction Scale and the Toxic Leadership Behaviors of Nurse Managers’ Scale | SPSS software version 26, descriptive and differential statistics | Job satisfaction acts as a mediating factor for toxic leadership behaviour and nurses’ turnover intentions |

References

- Benmira, S.; Agboola, M. Evolution of leadership theory. BMJ Lead. 2021, 5, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoria, P.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, M.; Sumaiya, B. Leadership Style and Organisational Success. World J. Engl. Lang. 2022, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogdu, A.L.F. Exploring Different Aspects of Nursing Leadership: An Integrative Review of Qualitative Studies. Mod. Care J. 2023, 20, e130402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, N.J. Leadership in nursing: The importance of recognising inherent values and attributes to secure a positive future for the profession. Collegian 2015, 22, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćeranić, J.; Peličić, D.; Saveljić, M. Building leadership in nursing practice. Sanamed 2024, 19, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashlan, M.A.; Alqhtani, N.A.; Alshaiban, A.M.; Alqahtani, M.M.S.; Alqahtani, M.S.M.; Alward, H.N.M.; Al Qahtani, M.M.A.; Alqahtani, M.S.M.; Hadi, R.L.B.L.; Assiri, A.H.M. Nursing Leadership and Its Impact on Healthcare Quality: A Systematic Review. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, C.; Sullivan, D. The nuts & bolts of being a nursing leader. Part 1: Leadership in nursing series. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2025, 20, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naemi, I.A. Nursing Leadership Role in Healthcare Transformation—A Critical Overview. Saudi J. Nurs. Health Care 2023, 6, 310–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rezende, H. How relational leadership can enhance nurses’ well-being and productivity. Nurs. Stand. 2024, 39, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalla, A.D.G.; Mostafa, W.H. Relationship between Toxic Leadership and Work Outcomes: A Cross-sectional Study. Egypt. J. Health Care 2023, 14, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J. Influence of nurse managers’ toxic leadership behaviours on nurse-reported adverse events and quality of care. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsadaan, N.; Alqahtani, M. Toxic Leadership in Emergency Nurses: Assessing Abusive Supervision and Its Team-Level Impacts on Conflict Management and Organizational Commitment. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 4271602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J. Toxic leadership and its relationship with outcomes on the nursing workforce and patient safety: A systematic review. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2024, 37, 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.A.; Hanges, P.J. Development and Validation of the Toxic Leadership Scale. Master’s Thesis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bas, B. Toxic Leadership in Education. Int. J. Educ. Adm. Manag. Leadersh. 2020, 1, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Fredricks-Lowman, I. Conflict in the workplace: A 10-year review of toxic leadership in higher education. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2020, 23, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltu, A.; Brouwers, M. Toxic leadership: Effects on job satisfaction, commitment, turnover intention and organisational culture within the South African manufacturing industry. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 18, a1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, K.L. Leader toxicity: An empirical investigation of toxic behavior and rhetoric. Leadership 2010, 6, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, I.; Maric, S.; Lončar, D. Defeating the Toxic Boss: The Nature of Toxic Leadership and the Role of Followers. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2020, 27, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satiani, B.; Satiani, A. Recognizing and Managing a Toxic Leader: A Case Study. Physician Leadersh. J. 2022, 9, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbogast, G.; Jadav, A. Investigating business toxic leadership. J. Manag. Eng. Integr. 2024, 17, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosetti, L.; Heffernan, T. The emotional and personal toll of higher education leadership. J. Educ. Adm. Hist. 2021, 53, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Chawla, S. Toxic Leadership in Workplaces: Insights from Bibliometric, Thematic Analysis, and TCM Framework. Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2024, 13, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodin, H.J. The nursing shortage in the United States of America: An integrative review of the literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 43, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Duff, J.; Munday, J. Perioperative Nursing Shortages: An Integrative Review of Their Impact, Causal Factors, and Mitigation Strategies. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 2983251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M. Time to solve persistent, pernicious and widespread nursing workforce shortages. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2023, 70, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, S.N.; Naicker, V. A review of the effect of nurse shortages on existing nurse workforces in South Africa and Ukraine. Technol. Audit. Prod. Reserves 2023, 4, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovner, C. COVID-19 and the supply and demand for Registered Nurses. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2022, 69, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaboyan, Y.S.; Pivkina, A.I. Nursing staff as a provider of safe and high-quality medical care. Public Health 2022, 2, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, H.; Dong, X.; Huang, X.; Li, B.; Wan, Q.; Shang, S. The effect of nurse staffing on patient-safety outcomes: A cross-sectional survey. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1758–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Ball, J.; Drennan, J.; Dall’Ora, C.; Jones, J.; Maruotti, A.; Pope, C.; Saucedo, A.R.; Simon, M. Nurse staffing and patient outcomes: Strengths and limitations of the evidence to inform policy and practice. A review and discussion paper based on evidence reviewed for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Safe Staffing guideline development. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 63, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Saville, C.; Rubbo, B.; Turner, L.Y.; Jones, J.; Griffiths, P. Nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 134, 104311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needleman, J.; Liu, J.; Shang, J.; Larson, E.L.; Stone, P.W. Association of registered nurse and nursing support staffing with inpatient hospital mortality. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2020, 29, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assaye, A.M.; Wiechula, R.; Schultz, T.J.; Feo, R. Impact of nurse staffing on patient and nurse workforce outcomes in acute care settings in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2021, 19, 751–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.E.; Murrells, T.; Rafferty, A.M.; Morrow, E.; Griffiths, P. ‘Care left undone’ during nursing shifts: Associations with workload and perceived quality of care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2014, 23, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, P.; Recio-Saucedo, A.; Dall, C.; Briggs, J.; Maruotti, A.; Meredith, P.; Smith, G.B.; Ball, J.; On behalf of the Missed Care Study Group. The association between nurse staffing and omissions in nursing care: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1474–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Lee, J.; You, S.J.; Song, K.J.; Hong, K.J. Nurse staffing, nurses prioritization, missed care, quality of nursing care, and nurse outcomes. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 26, e12803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, Z.; Palter, J.; Hardwick, J.; Moskoff, J.; Christian, E.; Bailitz, J. Decreased Nursing Staffing Adversely Affects Emergency Department Throughput Metrics. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 19, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marufu, T.C.; Collins, A.; Vargas, L.; Gillespie, L.; Almghairbi, D. Factors influencing retention among hospital nurses: Systematic review. Br. J. Nurs. 2021, 30, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveck, M.L.; Jones, C.B. The nursing practice environment, staff retention, and quality of care. Res. Nurs. Health 1996, 19, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mara, S.O. 121 The factors influencing nursing staff retention in the ICU setting: A scoping review. Ann. Work. Expo. Health 2024, 68, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, N.; Patton, D.; Moore, Z.; O’Connor, T.; Nugent, L.; Derwin, R. The Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Staff Nurse Retention in Hospital Settings: A Systematic Review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2023, 2023, 9577200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; De los Santos, J.A.A.; Falguera, C.C.; Nwafor, C.E.; Galabay, J.R.; Rosales, R.A.; Firmo, C.N. Predictors of nurses’ turnover intention at one and five years’ time. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2020, 67, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamanga, E.; Dyson, J.; Loke, J.; McKeown, E. Factors influencing the recruitment and retention of registered nurses in adult community nursing services: An integrative literature review. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2020, 21, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xiong, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, F.; He, J.; Xiang, Y.; Xu, C. Chinese nurses’ perceptions on toxic leadership behaviours of nurse managers: A qualitative study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 3256–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrah, O.; Alkhalaf, T.; Sharbatji, O. Toxic leadership as a predictor of physical and psychological withdrawal behaviours in the healthcare sector. J. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 164, 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakkal, E.; Serener, B.; Myrvang, N.A. Toxic Leadership and Turnover Intention: Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction. Rev. De Cercet. Si Interv. Soc. 2019, 66, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofei, A.M.A.; Poku, C.A.; Paarima, Y.; Barnes, T.; Kwashie, A.A. Toxic leadership behaviour of nurse managers and turnover intentions: The mediating role of job satisfaction. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossny, E.K.; Alotaibi, H.S.; Mahmoud, A.M.; Elcokany, N.M.; Seweid, M.M.; Aldhafeeri, N.A.; Abdelkader, A.M.; Elhamed, S.M.A. Influence of nurses’ perception of organizational climate and toxic leadership behaviors on intent to stay: A descriptive comparative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2023, 5, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; Nwafor, C.E.; Tsaras, K. Influence of toxic and transformational leadership practices on nurses’ job satisfaction, job stress, absenteeism and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1104–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofei, A.M.A.; Paarima, Y.; Barnes, T.; Poku, C.A. Toxic leadership behaviour of nurse managers on perceived job satisfaction and productivity of nursing workforce in sub-Saharan Ghana: A multi-centre cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 2733–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdan, A.H.A.; Eid, W.M. Toxic Leadership: Conflict Management Style and Organizational Commitment among Intensive Care Nursing Staff. Evid.-Based Nurs. Res. 2020, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, S.; Saeed, M.; Pahi, M.H.; Solangi, R.; Xin, C. They can’t treat you well under abusive supervision: Investigating the impact of job satisfaction and extrinsic motivation on healthcare employees. Ration. Soc. 2021, 33, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trépanier, S.-G.; Boudrias, V.; Peterson, C. Linking destructive forms of leadership to employee health. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erschens, R.; Seifried-Dübon, T.; Stuber, F.; Rieger, M.A.; Zipfel, S.; Nikendei, C.; Genrich, M.; Angerer, P.; Maatouk, I.; Gündel, H.; et al. The association of perceived leadership style and subjective well-being of employees in a tertiary hospital in Germany. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Y.M.; Sambasivan, M.; Ho, J.A. Impact of abusive supervision on counterproductive work behaviors of nurses. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2021, 59, 250–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Fatah Shipl, A.M.A.; Nabawy, Z.M.; Al anwer Ashour, H.M. The relationship between toxic leadership and nurses’ followership effectiveness. Cent. Eur. J. Nurs. Midwifery 2022, 13, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berma, A.; Mohamed, H.; Nosier, H. Organizational Silence as a Mediator Factor between Workplace Toxicity and Thriving among Nurses. Assiut Sci. Nurs. J. 2021, 9, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, O.; Erdal, N. The Mediating Role of Burnout Syndrome in Toxic Leadership and Job Satisfaction in Organizations. South East Eur. J. Econ. Bus. 2022, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrayyan, M.T. Effects of Nursing Leaders’ Toxic Leadership on Nurses’ Workplace Satisfaction, Job Engagement, and Turnover Intention: An Online Cross-Sectional Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 0, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J. Linking Toxic Leadership With Work Satisfaction and Psychological Distress in Emergency Nurses: The Mediating Role of Work-Family Conflict. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2024, 50, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaliem, S.M.F.; Zeid, M.A.G.A. The relationship between toxic leadership and organizational performance: The mediating effect of nurses’ silence. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukacik, E.-R.; Bourdage, J.S. Exploring the Influence of Abusive and Ethical Leadership on Supervisor and Coworker-Targeted Impression Management. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 771–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Nambudiri, R.; Selvaraj, P.; Sadh, A. A temporal study on subordinate’s response to destructive leadership: Voice withdrawal as a conflict coping mechanism. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2021, 32, 886–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, J. Destructive Leadership, Employees’ Voice, and Organization. In Diversity of Managerial Perspectives from Inside China. Managing the Asian Century; Foo, C., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Shetty, N. An empirical study on the impact of employee voice and silence on destructive leadership and organizational culture. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 11, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, S.A.; USMANI, S.; Raza, S. Effect of Despotic Leadership on the Employee Work Withdrawal Behavior and Acquiescent Silence. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2022, 4, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.M.; Shen, Y.; Chong, S. A dual-stage moderated mediation model linking authoritarian leadership to follower outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, X.; Sun, J.; Zheng, Y.; Graham, L.; Jiang, J. The virtue of a controlling leadership style: Authoritarian leadership, work stressors, and leader power distance orientation. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2024, 41, 507–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, W.; EldinFekry, N.; Elewa, A. Relationship between nurse manager leadership style and staff nurses’ work engagement. Egypt. Nurs. J. 2019, 16, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R.; Glazer, S.; Leiva, D. Leaders Condition the Work Experience: A Test of a Job Resources-Demands Model Invariance in Two Countries. J. Nurs. Manag. 2023, 2023, 1353289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, A.M.; Mahran, S.M.; Elseesy, N.A. A study of staff nurses’ perceptions of nursing leadership styles and work engagement levels in Saudi general hospitals. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2023, 10, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishgooie, A.H.; Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F.; Falcó-Pegueroles, A.; Lotfi, Z. Correlation between nursing managers’ leadership styles and nurses’ job stress and anticipated turnover. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specchia, M.L.; Cozzolino, M.R.; Carini, E.; Di Pilla, A.; Galletti, C.; Ricciardi, W.; Damiani, G. Leadership Styles and Nurses’ Job Satisfaction. Results of a Systematic Review. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellali, T.; Theodorou, P.; Psomiadi, M.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Platis, C.; Mpouzika, M.; Manomenidis, G. Assessing the Effect of Transactional Leadership and Empowerment on Nursing Staff’s Satisfaction: A Cross-Sectional Study. Florence Nightingale J. Nurs. 2024, 32, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, M.; Almansi, S.; Mrayyan, M.; ALBashtawy, M.; Aljezawi, M. Effect of nurse managers’ leadership styles on predicted nurse turnover. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 32, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gu, D.; Liang, C.; Zhao, S.; Ma, Y. How transformational leadership and clan culture influence nursing staff’s willingness to stay. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashaye, M.; Tilahun, D.; Belay, A.; Bereka, B. Perceived Utilization of Leadership Styles Among Nurses. Risk Manag. Heal. Policy 2023, 16, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malak, H.M.; Lorman, W.; Rundio, A.; Simion, D.; Simion, M.G. Predominantly practiced leadership styles of Chief Nursing Officers in healthcare organizations. J. Interprofessional Educ. Pract. 2022, 28, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahgob, G.A.-N.H.; Mohammed Abdallah Adam, S.; Mohamed El-sayed, S. Staff Nurses ’Perception Regarding Toxic Leadership Behavior of Head Nurses and it’s Relation to their Work Engagement. Egypt. J. Health Care 2024, 15, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palvimo, T.; Vauhkonen, A.; Hult, M. The Associations among Destructive Leadership, Job Demands and Resources, and Burnout among Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2023, 2023, 4289450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.; Palma-Moreira, A. Toxic Leadership and Turnover Intentions: The Role of Burnout Syndrome. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solehudin, S.; Syabanasyah, I. Impact of toxic leadership on nurses’ motivation, job satisfaction, productivity, and turnover intentions. J. Health Sci. Med. Ther. 2024, 2, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghini, F.; Fiorini, J.; Piredda, M.; Fida, R.; Sili, A. The relationship between nurse managers’ leadership style and patients’ perception of the quality of the care provided by nurses: Cross sectional survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 101, 103446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.O.; Zhang, J.; Fouad, A.S.; Mousa, K.; Nour, H.M. The Dark Side of Leadership: How Toxic Leadership Fuels Counterproductive Work Behaviors Through Organizational Cynicism and Injustice. Sustainability 2024, 17, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapalme, M.; Guerrero, S. How do I stand compared to agency workers? Justice perceptions and employees’ counterproductive work behaviours. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1471–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, M.B.; Alasan, I.I. Impact of Toxic Leadership on Counterproductive Work Behavior with the Mediating role of Psychological Contract Breach and Moderating role of Proactive Personality. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Aasland, M.S.; Skogstad, A. Destructive leadership behaviour: A definition and conceptual model. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L.G.; Bakker, A.B. Leadership and Job Demands-Resources Theory: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 722080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryee, S.; Chen, Z.X.; Sun, L.-Y.; Debrah, Y.A. Antecedents and outcomes of abusive supervision: Test of a trickle-down model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, B.J. Consequences of Abusive Supervision. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Hill, K.G.; Hennessey, B.A.; Tighe, E.M. The Work Preference Inventory: Assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 950–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. The Job Diagnostic Survey: An Instrument for the Diagnosis of Jobs and the Evaluation of Job Redesign. 1974, 1–87. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED099580.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Stilwell, D. A Longitudinal Study on the Early Development of Leader-Member Exchanges. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A. On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, M.S.; Ambrose, M.L. Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.J.; Robinson, S.L. Development of a measure of workplace deviance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, P.W.; Howell, J.P. Dimensions of National Culture and Effective Leadership Patterns: Hofstede Revisited; JAI Press: Stamford, CT, USA, 1988; pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Farh, J.L.; Hackett, R.D.; Liang, J. Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, H.; Korabik, K. Organizational Experiences and Propensity to Leave: A Multivariate Investigation of Men and Women Managers. J. Vocat. Behav. 1995, 46, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Term | Boolean Operator | Term | Boolean Operator | Term |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxic 1 Leadership | AND | Healthcare Organizations | ||

| Toxic Leadership | AND | Nursing Staff | ||

| Toxic Leadership | AND | Healthcare Organizations | AND | Nursing Staff |

| Toxic Leadership | OR | Nursing Staff | AND | Healthcare Organizations |

| Healthcare Organizations | OR | Nursing Staff | AND | Toxic Leadership |

| Characteristics | Studies n (%) |

|---|---|

| Area of Studies | |

| Europe | 2 (11.1) |

| Asia | 8 (44.4) |

| USA | 1 (5.6) |

| Africa | 7 (38.9) |

| Year of publication | |

| 2019 | 3 (16.7) |

| 2020 | 2 (11.1) |

| 2021 | 2 (11.1) |

| 2022 | 5 (27.8) |

| 2023 | 3 (16.7) |

| 2024 | 2 (11.1) |

| 2025 | 1 (5.6) |

| Type of studies | |

| quantitative study | 10 (55.6) |

| qualitative study | 2 (11.1) |

| mixed methods | 6 (33.3) |

| Categorization of studies | |

| key dimensions shaping perceptions of toxic leadership | 5 (27.8) |

| impact of toxic leadership on nursing staff retention | 13 (72.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsapnidou, E.; Moudatsou, M.; Katharakis, G.; Koukouli, S.; Rovithis, M.; Kelesi, M.; Stavropoulou, A. The Impact of Toxic Leadership on Nurse Retention: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2341. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182341

Tsapnidou E, Moudatsou M, Katharakis G, Koukouli S, Rovithis M, Kelesi M, Stavropoulou A. The Impact of Toxic Leadership on Nurse Retention: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2341. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182341

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsapnidou, Eleni, Maria Moudatsou, George Katharakis, Sofia Koukouli, Michael Rovithis, Martha Kelesi, and Areti Stavropoulou. 2025. "The Impact of Toxic Leadership on Nurse Retention: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2341. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182341

APA StyleTsapnidou, E., Moudatsou, M., Katharakis, G., Koukouli, S., Rovithis, M., Kelesi, M., & Stavropoulou, A. (2025). The Impact of Toxic Leadership on Nurse Retention: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 13(18), 2341. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182341