Origins and Previous Experiences from a Gender Perspective on the Perception of Pain in Nursing Students: Study Protocol

Abstract

1. Introduction

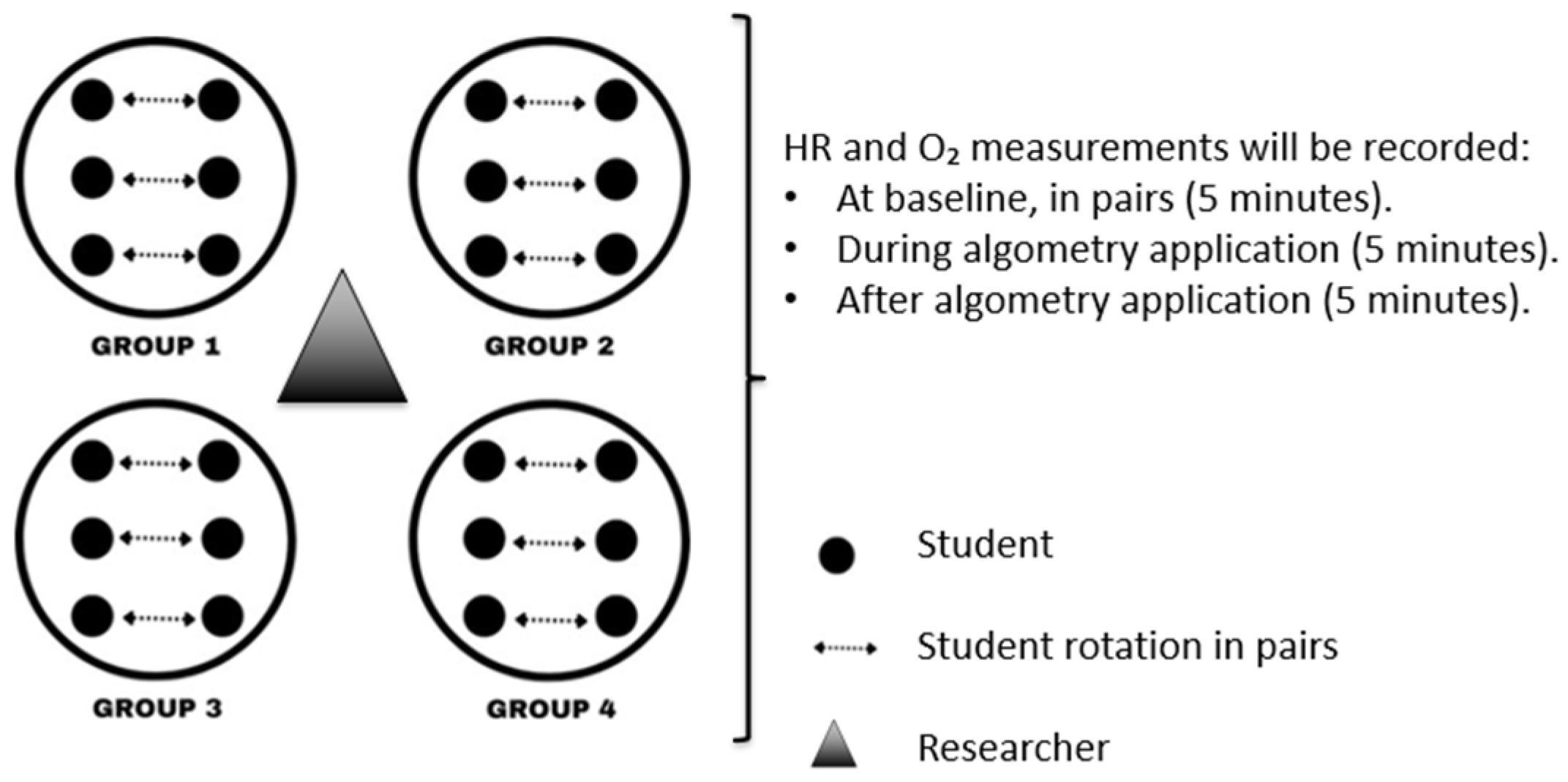

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- For students: to increase knowledge about total pain and pediatric pain; increase knowledge about non-pharmacological therapies for pediatric pain management and their practical application; to improve critical thinking; open up to sexual, social, gender and cultural diversity, and study how this impacts the perception of pain.

- (2)

- For university lecturers: to increase skills/competences in non-pharmacological treatments; using innovative pedagogical approaches, in different modalities (face-to-face/distance learning).

- (3)

- For universities involved in the project: to facilitate theoretical and practical studies in total pain and non-pharmacological management of pediatric pain; possibility of mobility and cooperation between partners; to develop innovative educational approaches (gamification); to produce face-to-face/distance learning formats; strengthen inter-university networks.

- (4)

- For higher education degrees outside the project: to facilitate free access to distance learning formats on pain. This research will promote education at the international level in different higher education health courses at the member universities of this study.

- Outcome 1.

- Outcome 2.

- (1)

- Heart rate (HR) measurement technique and reference values in pediatrics.

- (2)

- (3)

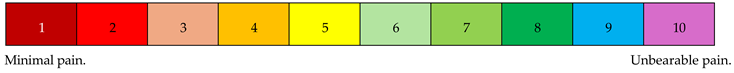

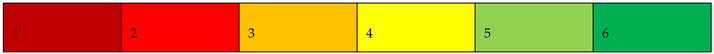

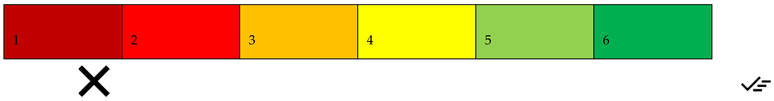

- Algometry technique to determine the minimum pressure perceived by the participant as painful [65,66]. By gradually increasing the applied force on the skin, sensations progress from touch to pressure and finally to pain [67,68]. At specific measurement points (Table 1 and Table 2), students will rate pain intensity using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). The device will then be removed, and pain intensity will be recorded again using the VAS.

- (4)

- Cold Pressor Test (CPT) [69] to assess pain threshold, tolerance, and intensity.

- Outcome 3.

- Outcome 4.

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IASP | International Association for the Study of Pain |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| NICUs | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| ACEs | Adverse Childhood Experiences |

| HE | Higher Education |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| VAS | Visual Analogic Scale |

| CPT | Cold Pressor Test |

Appendix A

| Anatomical Point | Side | Measurement 1 (N) | Pain (VAS1) | Measurement 2 (N) | Pain (VAS2) | Measurement 3 (N) | Pain (VAS3) | Mean (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Trapezius | Right | |||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Upper Trapezius | Left | |||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Occipital | Right | |||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Cervical Spine | Right | |||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Second Rib | Right | |||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Knee (Medial side) | Right | |||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Knee (Medial side) | Left | |||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Lateral Epicondyle | Right | |||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Greater Trochanter | Right | |||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Anatomic Point (2) | Measurement 1 (N) | Measurement 2 (N) | Measurement 3 (N) | Mean (N) | ||||

| Glabella | ||||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Right Forearm | ||||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Right Knee (Lateral side) | ||||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Right Metatarsus | ||||||||

| HR: | HR: | HR: | ||||||

| O2: | O2: | O2: | ||||||

| Time (s) | Pain (VAS) |

| Time (s) | Pain (VAS) |

| Source: own elaboration based on Buskila research [67]. | |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Specific Questionnaire for Women

- 1.

- At what age did you start menstruating?

| <12 years | Between 12 and 14 years | Between 15 and 17 years | >18 years |

- 2.

- Are your menstrual cycles regular?

- YES

NO

- 3.

- Indicate menstrual cycle frequency:

| <28 days | 28–32 days | ||

| >32 days | Irregular Cycles |

- 4.

- Do you usually experience menstrual pain (dysmenorrhea)?

- YES

NO

- (If no, skip to question 10)

- 5.

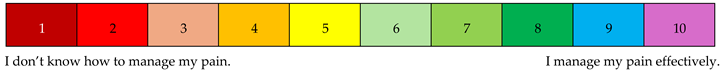

- Evaluate your menstrual pain on a scale from 1 to 10:

- 6.

- 7.

- Which pattern describes your menstrual pain?

-

- Pain before bleeding, intense, then decreases

-

- Consistently intense pain throughout

-

- Mild but persistent pain

-

- Very mild pain that progressively disappears

-

- 8.

- Do you think your menstrual pain experience influences your perception of other types of pain?

- YES

NO

- 9.

- Do you think men tolerate pain better than women?

- YES

NO

- 10.

- What methods do you use to alleviate menstrual pain?

-

- Pharmacological analgesia

-

- Walking

-

- Relaxing baths

-

- Heat application

-

- Other: ________

-

- 11.

- Which drugs do you use? (multiple options possible):

|

| Have you ever needed oral contraceptives (OC) for menstrual pain? YES  NO NO  Are you currently taking OC? YES  NO NO  |

- 1.

- Do you believe there is sufficient health education on menstrual pain prevention/management in your health/educational environment?

- YES

NO

- 2.

- Do you consider healthcare professionals important in managing menstrual pain?

- YES

NO

- 3.

- Evaluate on a Likert scale your satisfaction with the socio-health care received during menstruation:

Appendix B.2. Specific Questionnaire for Men

- 1.

- Do you think students should receive more training on menstrual pain to better understand their patients?

- YES

NO

- 2.

- Menstrual pain can be disabling and significantly affect women’s daily activities.

| True | |

| False |

- 3.

- Do you think men tolerate pain better than women?

- YES

NO

- 4.

- Indicate how important you think each of the following strategies is for managing menstrual pain:

- (a)

- Pharmacological therapy as a method to address menstrual pain and improve women’s quality of life

- (b)

- Non-pharmacological therapy (yoga, acupuncture, and relaxation techniques) as a method to address menstrual pain and improve women’s quality of life.

- 5.

- Do you consider that, in your healthcare and/or educational environment (high schools, universities, health centers, etc.), there is sufficient health education on the prevention and management of menstrual pain?

- YES

NO

- 6.

- Do you consider healthcare professionals important in addressing menstrual pain?

- YES

NO

- 7.

- Do you think it is more common for men to ignore pain or delay going to the doctor compared to women?

- YES

NO

- 8.

- What do you think is the main reason men tend to avoid going to the doctor for pain?

-

- Fear of receiving bad news

-

- Lack of time

-

- Belief that “the pain will go away on its own without professional help”

-

- Preference for handling pain with home remedies or self-medication

-

- 9.

- What type of pain do you think is most prevalent in the male population?

-

- Back pain, especially lower back pain

-

- Muscle and joint pain

-

- Abdominal or groin pain

-

- Testicular pain

-

- 10.

- Indicate which factor you believe is most relevant in the difference in pain self-perception according to sex (choose only one option):

-

- The different hormones in the body influence the pain threshold and tolerance between men and women.

-

- The attitude toward pain in terms of openly expressing it influences the pain threshold and tolerance between men and women.

-

- Seeking medical help influences the pain threshold and tolerance between men and women.

-

- 11.

- Regarding testicular pain from trauma (blow), do you consider it a medical emergency?

- YES

NO

- 12.

- Regarding testicular pain from trauma, do you think there is a risk of serious complications such as a testicular hematoma, testicular torsion, or even rupture of the testicular membrane?

- YES

NO

- 13.

- If you have ever suffered testicular trauma, did you go to the doctor to assess the situation to prevent possible complications and/or treat the associated pain?

- YES

NO

Appendix B.3. General Questionnaire

| Nursing Degree | Degree in Physiotherapy | |

| 1st Year | ||

| 2nd Year | ||

| 3rd Year | ||

| 4th Year | ||

| Gender | Female | Male | Others | |||||

| Age | 18–25 | 26–33 | 33–40 | >40 | ||||

| University | UCLM (Toledo) | UCLM (Albacete) | UFV |

- Do you work while studying?: YES

/NO

- Do you have family responsibilities?: YES

/NO

- 1.

- In which week or month of gestation (WG) were you born?

| Less than 37 WG | Between 37–40 WG | More than 40 WG |

- 2.

- If you were born before 37 weeks of gestation, how many weeks exactly were you born?

- ____________________________________________________

- 3.

- How much did you weigh at birth?

- ____________________________________________________

- 4.

- If you know your APGAR score at birth, indicate it numerically:________________________________________________________

- 5.

- Were you born via vaginal delivery (natural/eutocic)?

- YES

NO

- 6.

- If not, which method was used?

-

- Instrume-Forceps-assisted

-

- Spatula-assisted

-

- Vacuum-assisted

-

- Cesarean

-

- Other: ________

-

- 7.

- Have you ever been admitted to the Neonatal or Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (NICU or PICU)?

- YES

NO

- 8.

- Have you ever been hospitalized?

- YES

NO

- 9.

- If yes, complete the following

- Age of admission: ________

- Length of stay (days): ________

- Reason for admission: ________

- Did you experience pain during hospitalization

- YES

NO

- 10.

- Do you have any disease that causes pain?

- YES

NO

- ____________________________________________________

- ____________________________________________________

- ____________________________________________________

- 11.

- If yes, which one?

- 12.

- What type of healthcare center do you usually attend?

- Private

Public

- 13.

- If you experience pain

- a.

- Do you seek healthcare assistance?

- b.

- Do you try to manage it at home by yourself?

- 14.

- Do you try to manage it at home by yourself?

- Rate your self-management capability from 1 to 10:

- 15.

- What measures do you usually take to relieve pain?

-

- Pharmacological analgesia

-

- Walking

-

- Relaxing baths

-

- Applying heat to the painful area (seed bags, hot water bottles)

-

- Other methods: ________

-

- 16.

- If using pharmacological measures, which drugs do you usually take? (select all that apply):

|

| Have you taken any of these drugs in the last 24 h? YES  NO NO  If yes, indicate which: ________________________ |

|

- 17.

- What type of physical activity do you regularly do?

| Grade 0: Hiking only, walking to university/work, household chores | |

| Grade 1: Minimum WHO activity guidelines (2.5–5 h/week moderate or 1.5–2 h/week intense activity, group sports) | |

| Grade 2: Local competitive level | |

| Grade 3: National competitive level | |

| Grade 4: International competitive level |

- Indicate which sport: ________________________________________________________

References

- Anand, K.J.; Craig, K.D. New perspectives on the definition of pain. Pain 1996, 67, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydede, M. Does the IASP definition of pain need updating? PAIN Rep. 2019, 4, e777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, S.B.O.; de Macedo Barbosa, S.M.; Carneiro Neves, C.; Luiz Ferreira, E.A.; de Araujo Torreao, L.; Michalowski, M.B.; de Oliveira, N.F.; Molinari, P.C.C.; Moraes, C.V.B. Dores Comuns em Pediatria: Avaliação e Abordagem; Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria: São Paulo, Brazil, 2024; Volume 111. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSantana, J.M.; Perissinotti, D.M.N.; Oliveira Junior, J.O.; Correia, L.M.F.; Oliveira, C.M.; Fonseca, P.R.B. Revised definition of pain after four decades. BrJP 2020, 3, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J. Cicely Saunders, ‘Total Pain’ and emotional evidence at the end of life. Med. Humanit. 2022, 48, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, M.; Tan, Z.; Chen, J.; Weidig, T.; Xu, W.; Cong, X.S. Neonatal pain: Perceptions and current practice. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 30, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittz, E.; Malloy-Diniz, L.F. Dor neonatal e desenvolvimento neuropsicológico. Rev. Min. Enferm. 2006, 10, 266–270. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, K.J.; Hickey, P.R. Pain and its effects in the human neonate and fetus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, L.A. Neonatal pain: What’s age got to do with it? Surg. Neurol. Int. 2014, 5 (Suppl. S13), S479–S489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostovic, I.; Rakic, P. Developmental history of the transient subplate zone in the visual and somatosensory cortex of the macaque monkey and human brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990, 297, 441–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M.; Houdou, S.; Mito, T.; Takashima, S.; Asanuma, K.; Ohno, T. Development of myelination in the human fetal and infant cerebrum: A myelin basic protein immunohistochemical study. Brain Dev. 1992, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, R.; Fabrizi, L.; Worley, A.; Meek, J.; Boyd, S.; Fitzgerald, M. Premature infants display increased noxious-evoked neuronal activity in the brain compared to healthy age-matched term-born infants. Neuroimage 2010, 52, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, C.S.; Muzi, S.; Rogier, G.; Meinero, L.L.; Marcenaro, S. The adverse childhood experiences—International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) in community samples around the world: A systematic review (part I). Child Abuse Negl. 2022, 129, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy Gigi, E.; Rachmani, M.; Defrin, R. The relationship between traumatic exposure and pain perception in children: The moderating role of posttraumatic symptoms. Pain 2024, 165, 2274–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanis, M.; Outadi, A.; Choi, F. Early childhood trauma, substance use and complex concurrent disorders among adolescents. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, K.S.; O’Leary, D.D.; MacNeil, A.J.; Hodges, G.J.; Wade, T.J. Linking the hemodynamic consequences of adverse childhood experiences to an altered HPA axis and acute stress response. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 93, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soee, A.-B.L.; Skov, L.; Kreiner, S.; Tornoe, B.; Thomsen, L.L. Pain sensitivity and pericranial tenderness in children with tension-type headache: A controlled study. J. Pain Res. 2013, 6, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohsel, K.; Hohmeister, J.; Oelkers-Ax, R.; Flor, H.; Hermann, C. Quantitative sensory testing in children with migraine: Preliminary evidence for enhanced sensitivity to painful stimuli especially in girls. Pain 2006, 123, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, M.; Roofthooft, D.W.; Anand, K.J.; Guldemond, F.; de Graaf, J.; Simons, S.; de Jager, Y.; van Goudoever, J.; Tibboel, D. Taking up the challenge of measuring prolonged pain in (premature) neonates: The COMFORTneo scale seems promising. Clin. J. Pain 2009, 25, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, J.K.; Dobson, K.S.; Madigan, S.; Yeates, K.O.; Stone, A.L.; Wilson, A.C.; Salberg, S.; Mychasiuk, R.; Noel, M. Adverse childhood experiences in parents of youth with chronic pain: Prevalence and comparison with a community-based sample. PAIN Rep. 2020, 5, e866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craner, J.R.; Lake, E.S.; Barr, A.C.; Kirby, K.E.; O’Neill, M. Childhood adversity among adults with chronic pain: Prevalence and association with pain-related outcomes. Clin. J. Pain 2022, 38, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beal, S.J.; Kashikar-Zuck, S.; King, C.; Black, W.; Barnes, J.; Noll, J.G. Heightened risk of pain in young adult women with a history of childhood maltreatment: A prospective longitudinal study. Pain 2020, 161, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, K.G.; Widom, C.S. Post-traumatic stress disorder moderates the relation between documented childhood victimization and pain 30 years later. Pain 2011, 152, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarz, J.; Eich, W.; Treede, R.-D.; Gerhardt, A. Altered pressure pain thresholds and increased wind-up in adult patients with chronic back pain with a history of childhood maltreatment: A quantitative sensory testing study. Pain 2016, 157, 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarinci, I.C.; McDonald-Haile, J.; Bradley, L.A.; Richter, J.E. Altered pain perception and psychosocial features among women with gastrointestinal disorders and history of abuse: A preliminary model. Am. J. Med. 1994, 97, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Advice of the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture to States Parties and National Preventive Mechanisms Relating to the Coronavirus Pandemic (Adopted on 25 March 2020). Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/OPCAT/AdviceStatePartiesCoronavirusPandemic2020.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. Prevention and management of procedural pain in the neonate: An update. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunau, R.E.; Craig, K.D. Pain expression in neonates: Facial action and cry. Pain 1987, 28, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, P.; Puchalski, M.; Creech, S.D.; Weiss, M.G. Clinical reliability and validity of the N-PASS: Neonatal pain, agitation and sedation scale with prolonged pain. J. Perinatol. 2008, 28, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, J.; Alcock, D.; McGrath, P.; Kay, J.; MacMurray, S.B.; Dulberg, C. The development of a tool to assess neonatal pain. Neonatal Netw. 1993, 12, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pud, D.; Aamar, S.; Schiff-Keren, B.; Sheinfeld, R.; Brill, S.; Robinson, D.; Fogelman, Y.; Habib, G.; Sharon, H.; Amital, H.; et al. Chronic pain in adolescence: Prevalence, impact, and clinical implications. PAIN Rep. 2024, 9, e1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancora, G.; Lago, P.; Garetti, E.; Pirelli, A.; Merazzi, D.; Pierantoni, L.; Ferrari, F.; Faldella, G. Follow-up at the corrected age of 24 months of preterm newborns receiving continuous infusion of fentanyl for pain control during mechanical ventilation. Pain 2017, 158, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, J.; van Lingen, R.A.; Simons, S.H.; Anand, K.J.; Duivenvoorden, H.J.; Weisglas-Kuperus, N.; Roofthooft, D.W.; Groot Jebbink, L.J.; Veenstra, R.R.; Tibboel, D.; et al. Long-term effects of routine morphine infusion in mechanically ventilated neonates on children’s functioning: Five-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Pain 2011, 152, 1391–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, S.A.; Ward, W.L.; Paule, M.G.; Hall, R.W.; Anand, K.J. A pilot study of preemptive morphine analgesia in preterm neonates: Effects on head circumference, social behavior, and response latencies in early childhood. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2012, 34, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocek, M.; Wilcox, R.; Crank, C.; Patra, K. Evaluation of the relationship between opioid exposure in extremely low birth weight infants in the neonatal intensive care unit and neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years. Early Hum. Dev. 2016, 92, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranger, M.; Synnes, A.R.; Vinall, J.; Grunau, R.E. Internalizing behaviours in school-age children born very preterm are predicted by neonatal pain and morphine exposure. Eur. J. Pain 2014, 18, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, T.; Shepherd, E.; Tobias, J.D. Neonatal pain management. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2014, 8 (Suppl. S1), S89–S97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.W.; Shbarou, R.M. Drugs of choice for sedation and analgesia in the neonatal ICU. Clin. Perinatol. 2009, 36, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Gao, H.; Xu, G.; Li, M.; Du, S.; Li, F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D. Efficacy and safety of repeated oral sucrose for repeated procedural pain in neonates: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 62, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Jiang, Y.F.; Li, F.; Tong, Q.H.; Rong, H.; Cheng, R. Effect of combined music and touch intervention on pain response and β-endorphin and cortisol concentrations in late preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.C.; Caminha, M.F.; Coutinho, A.C.; Ventura, C.M. Pain in the neonatal unit: The knowledge, attitude and practice of the nursing team. Cogitare Enferm. 2016, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sposito, N.P.B.; Rossato, L.M.; Bueno, M.; Kimura, A.F.; Costa, T.; Guedes, D.M.B. Assessment and management of pain in newborns hospitalized in a neonatal intensive care unit: A cross-sectional study. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2017, 25, e2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Delaney, C.; Vazquez, V. Neonatal nurses’ perceptions of pain assessment and management in NICUs: A national survey. Adv. Neonatal Care 2013, 13, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, M.; Lane-Krebs, K.; Matthews, J.; Johnston-Devin, C. Student nurses’ pain knowledge and attitudes towards pain management over the last 20 years: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 108, 105169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grommi, S.; Vaajoki, A.; Voutilainen, A.; Kankkunen, P. Effect of pain education interventions on registered nurses’ pain management: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2023, 24, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, C.; Feeney, A.; Basa, M.; Eustace-Cook, J.; McCann, M. Nurses knowledge, attitudes and education needs towards acute pain management in hospital settings: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 4325–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L. Effect of educational interventions for improving the nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice of paediatric pain management: A aystematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2024, 25, e271–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innab, A.; Alammar, K.; Alqahtani, N.; Aldawood, F.; Kerari, A.; Alenezi, A. The impact of a 12-hour educational program on nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding pain management: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samulowitz, A.; Gremyr, I.; Eriksson, E.; Hensing, G. “Brave Men” and “Emotional Women”: A theory-guided literature review on gender bias in healthcare and gendered norms towards patients with chronic pain. Pain Res. Manag. 2018, 2018, 6358624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). IASP 2023 Global Year for Integrative Pain Care. 2024. Available online: https://www.iasp-pain.org/advocacy/global-year/integrative-pain-care/ (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Osborne, N.R.; Davis, K.D. Sex and gender differences in pain. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2022, 164, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, K.J. Sex and gender issues in pain management. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2020, 102 (Suppl. S1), 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, C.J.; Campbell, C.M.; Edwards, R.R.; Dobs, A.S. Sex-based differences in pain perception and treatment. Pain Med. 2009, 10, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.; Barnett, C.; Katzberg, H.D.; Lovblom, L.E.; Perkins, B.A.; Bril, V. Sex differences in neuropathic pain intensity in diabetes. J. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 388, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taves, S.; Berta, T.; Liu, D.L.; Gan, S.; Chen, G.; Kim, Y.H.; Ji, R.R. Spinal inhibition of p38 MAP kinase reduces inflammatory and neuropathic pain in male but not female mice: Sex-dependent microglial signaling in the spinal cord. Brain Behav. Immun. 2016, 55, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorge, R.E.; Mapplebeck, J.C.; Rosen, S.; Beggs, S.; Taves, S.; Alexander, J.K.; Mogil, J.S. Different immune cells mediate mechanical pain hypersensitivity in male and female mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1081–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet. Managing pain effectively. Lancet 2011, 377, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.; Gaffiero, D. Exploring the lived experiences of patients with fibromyalgia in the United Kingdom: A study of patient-general practitioner communication. Psychol. Health 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpin, M.C.; Ferreira, E.L.; Eduardo, A.A.; Bombarda, T.B. Ensino sobre cuidados paliativos nos cursos da área de saúde: Apontamentos sobre lacunas e caminhos. Diálogos Interdisc. 2022, 11, 140–153. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, A.; Gaffiero, D. Between the Lines: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis Exploring Injury, Mental Health and Support in Professional and Semi-Professional Football in the United Kingdom. Cogent Psychol. 2025, 12, 2537216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS). Aspectos Técnicos y Regulatorios Sobre el uso de Oxímetros de Pulso en el Monitoreo de Pacientes con COVID-19; OPS/HSS/MT/COVID-19/20-0029; 7 de Agosto de 2020. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52551 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Evans, D.W.; De Nunzio, A.M. Controlled manual loading of body tissues: Towards the next generation of pressure algometer. Chiropract. Man. Ther. 2020, 28, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenik, G.; Graça, G.; Carvalho, E.; de Santana, J. Desenvolvimento de sistema de algometria de pressão. Oncology 2011, 23, 381–386. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.H.; Kilgour, R.D.; Comtois, A.S. Test–retest reliability of pressure pain threshold measurements of the upper limb and torso in young healthy women. J. Pain 2007, 8, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buskila, D.; Neumann, L.; Zmora, E.; Feldman, M.; Bolotin, A.; Press, J. Pain sensitivity in prematurely born adolescents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2003, 157, 1079–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, C.; Muñoz, T.; Chamorro, C. Monitorización del dolor: Recomendaciones del grupo de trabajo de analgesia y sedación de la SEMICYUC. Med. Intensiv. 2006, 30, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ganzewinkel, C.-j.J.L.M.; Been, J.V.; Verbeek, I.; van der Loo, T.B.; van der Pal, S.M.; Kramer, B.W.; Andriessen, P. Pain threshold, tolerance and intensity in adolescents born very preterm or with low birth weight. Early Hum. Dev. 2017, 110, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt-Watson, J.; Hogans, B. Current Status of Pain Education and Implementation Challenges. IASP. 2021. Available online: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/current-status-of-pain-education-and-implementation-challenges/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Watt-Watson, J.; Peter, E.; Clark, A.J.; Dewar, A.; Hadjistavropoulos, T.; Morley-Forster, P.; O’Leary, C.; Raman-Wilms, L.; Unruh, A.; Webber, K.; et al. The ethics of Canadian entry-to-practice pain competencies: How are we doing? Pain Res. Manag. 2013, 18, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt-Watson, J.; Murinson, B. Current challenges in pain education. Pain Manag. 2013, 3, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, A.; Smith, B.; Blyth, F. Pain and the global burden of disease. Pain 2016, 157, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedrez, E.S.; Monteiro, J.K. Pain assessment in pediatrics. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20190109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccioli, S.C.; Tacla, M.T.G.M.; Rossetto, E.G.; Collet, N. The management of pediatric pain and the perception of the nursing team in light of the Social Communication Model of Pain. BrJP 2020, 3, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Basic Documents, 48th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, M.; Currow, D.C.; Ekström, M.P. Exploring the most important factors related to self-perceived health among older men in Sweden: A cross-sectional study using machine learning. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e061242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jylhä, M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, M.T.Á.D.; dos Santos, V.P.; do Carmo, M.B.B.; de Souza, A.C.; França, C.P.X. Relação entre a autopercepção do estado de saúde e a automedicação entre estudantes universitários. Rev. Psicol. Divers. Saúde 2017, 6, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensitive Point | Anatomical Area | Side(s) Evaluated | Anatomical Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Trapezius | Trapezius | Right and left | Midpoint of the upper trapezius muscle (midway between the occiput and the acromion) |

| Occipital | Occipital | Right | Below the occipital prominence |

| Cervical Spine | Cervical Column | Right | Intertransverse space between C5 and C7 |

| Second Rib | Second Rib | Right | On the superior surface, just lateral to the costochondral junction (sternum and costal cartilage) |

| Knees (medial side) | Knees | Right and left | In the medial adipose pad, over the medial collateral ligament (3 cm lateral to the medial border of the patella) |

| Lateral Epicondyle | Lateral Epicondyle | Right | 2 cm distal (toward the wrist) to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus |

| Greater Trochanter | Greater Trochanter | Right | 2 cm posterior to the greater trochanter of the femur (palpating the posterior border of the greater trochanter) |

| Control Point | Anatomical Description |

|---|---|

| Glabella | Area between the eyebrows, above the nasal bridge |

| Right Forearm | Distal third of the right forearm (the forearm is divided into thirds and a consistent point is selected for each participant within this area) |

| Right Knee | Lateral aspect of the knee (3 cm lateral to the midline of the patella) |

| Right Metatarsus | Shaft of the third metatarsal of the right foot |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Pozuelo, J.M.; Crespo-Cañizares, A.; Hernández-Iglesias, S.; García-Magro, N.; López-González, Á.; Lopezosa-Villajos, V.; Hermida-Mota, M.; Gómez-Cantarino, S. Origins and Previous Experiences from a Gender Perspective on the Perception of Pain in Nursing Students: Study Protocol. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182276

Pérez-Pozuelo JM, Crespo-Cañizares A, Hernández-Iglesias S, García-Magro N, López-González Á, Lopezosa-Villajos V, Hermida-Mota M, Gómez-Cantarino S. Origins and Previous Experiences from a Gender Perspective on the Perception of Pain in Nursing Students: Study Protocol. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182276

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Pozuelo, Juan Manuel, Almudena Crespo-Cañizares, Sonsoles Hernández-Iglesias, Nuria García-Magro, Ángel López-González, Victoria Lopezosa-Villajos, Miriam Hermida-Mota, and Sagrario Gómez-Cantarino. 2025. "Origins and Previous Experiences from a Gender Perspective on the Perception of Pain in Nursing Students: Study Protocol" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182276

APA StylePérez-Pozuelo, J. M., Crespo-Cañizares, A., Hernández-Iglesias, S., García-Magro, N., López-González, Á., Lopezosa-Villajos, V., Hermida-Mota, M., & Gómez-Cantarino, S. (2025). Origins and Previous Experiences from a Gender Perspective on the Perception of Pain in Nursing Students: Study Protocol. Healthcare, 13(18), 2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182276