Effectiveness of the Research Practice Ability Enhancement Program on Evidence-Based Practice Competencies in Clinical Nurses: A Non-Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How does the RPAEP affect the research practice abilities of clinical nurses?

- What changes have occurred in the practice of clinical nurses after participating in the RPAEP?

- Based on these research questions, we formulated the following hypotheses:

- Primary hypothesis:

- The RPAEP will significantly improve research practice ability (RPA) scores in the intervention group compared to those in the control group.

- Secondary hypotheses:

- The intervention group will demonstrate significantly higher EBP belief (EBPB) scores compared to the control group following the RPAEP.

- The intervention group will show significantly improved EBP Attitude (EBPA) scores compared to the control group.

- The intervention group will exhibit significantly enhanced Nursing Professional Value Scale (NPVS) scores compared to the control group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting and Sample

2.3. Ethical Consideration

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. RPA

2.4.2. EBPB

2.4.3. EBPA

2.4.4. NPVs

2.5. Procedure

2.5.1. Development of the RPAEP

2.5.2. Application of the RPAEP

2.6. Data Collection

2.6.1. Quantitative Data Collection

2.6.2. Qualitative Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Comparison of Research Variables Between Experimental and Control Groups in the RPAEP

3.3. Barriers to Research and Changes Based on Participation in the RPAEP

3.3.1. Theme 1. Barriers to Research Practice

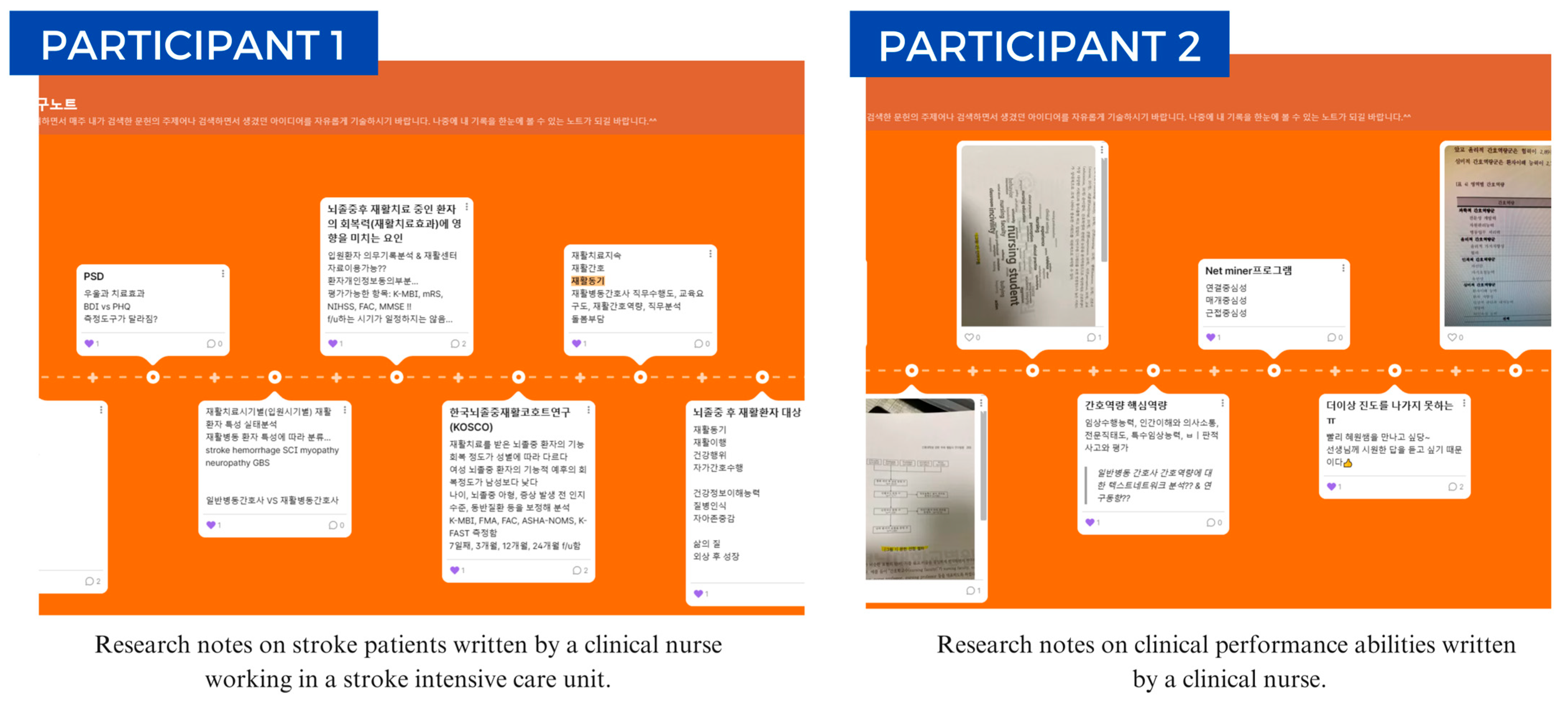

3.3.2. Theme 2. Guidance for Research Practice

3.3.3. Theme 3. Enhancing Research Practice Ability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RPAEP | Research Practice Ability Enhancement Program |

| EBP | Evidence-Based Practice |

| EBPB | Evidence-Based Practice Belief |

| EBPA | Evidence-Based Practice Attitude |

| ARCC | Advancing Research and Clinical Practice through Close Collaboration |

| NPVS | Nursing Professional Value Scale |

| RPA | Research Practice Ability |

| FGIs | Focus Group Interviews |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

References

- Melnyk, B.M.; Fineout-Overholt, E. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing & Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice, 5th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 1–936. [Google Scholar]

- Sarawad, S.S. Evidence-based practice in nursing-a review. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Res. 2023, 11, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, A.; Grande, G.; Luker, K. Strategies, facilitators and barriers to implementation of evidence-based practice in community nursing: A systematic mixed-studies review and qualitative synthesis. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2019, 20, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, K. Barriers to conducting and publishing research among nursing faculty members at Shaqra University, Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 7048–7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khunou, S.H.; Matlhaba, K.L. Literature review: The support needs of the nurse mentors in their mentoring role. J. Ners. Midwifery 2023, 10, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadaan, N.; Ramadan, O.M.E. Barriers and facilitators in implementing evidence-based practice: A parallel cross-sectional mixed methods study among nursing administrators. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.; Gibson, J.; Lewis, J.; Strickland, K.; Paterson, C. Decision-making in nursing research and practice—Application of the cognitive continuum theory: A meta-aggregative systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 7979–7995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.E.; Kim, W.G.; Lim, Y.J. An analysis of evidence-based practice courses in Korean nursing education systems. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, P.; Sutphen, M.; Leonard, V.; Day, L. Educating Nurses: A Call for Radical Transformation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, D.; Park, C.; Sugimoto, K.; Jeon, M.; Kim, D.; Eun, Y. Effectiveness of an evidence-based practice education program for undergraduate nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, M.Y. Effects of metaverse-based career mentoring for nursing students: A mixed methods study. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, H.W. Developing and evaluating an evidence-based practice research competency enhancement program for clinical nurses in Korea: A pilot study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, E.; Fitzpatrick, S. Mentorship education for advanced practice registered nurses. J. Dr. Nurs. Pract. 2023, 16, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Nwamu, H.; Lama, A. Building confidence, diminishing stress: A clinical incivility management initiative for nursing students. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2485–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prummer, K.; Human-Vogel, S.; Graham, M.A.; Pittich, D. The role of mentoring in developing leaders’ emotional intelligence: Exploring mentoring types, emotional intelligence, organizational factors, and gender. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1393660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.G.; Yang, Y.L.; Sung, J.H.; Park, C.G.; Chang, A.M. Psychometric properties of Korean version of self-efficacy of evidence-based practice scale. Asian Nurs. Res. 2016, 10, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Essex, R.; Kennedy, J.; Miller, D.; Jameson, J. A scoping review exploring the impact and negotiation of hierarchy in healthcare organisations. Nurs. Inq. 2023, 30, e12571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomotaki, A.; Fukahori, H.; Sakai, I. Exploring sociodemographic factors related to practice, attitude, knowledge, and skills concerning evidence-based practice in clinical nursing. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 17, e12260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arian, M.; Nobahar, M.; Raiesdana, N.; Oghazian, M.B. Identifying the fields of activity, challenges and positive outcomes of nursing prescription: A systematic review. Hayat 2018, 24, 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, H.W.; Kim, S.A. The impact of a Research Practice Ability Enhancement Program (RPAEP) for clinical nurses: A mixed-method study. In Proceedings of the Korean Society of Nursing Science Fall Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 18 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.K. Development of program outcome self-assessment tool in Korean nursing baccalaureate education. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2015, 21, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Fineout-Overholt, E.; Mays, M.Z. The evidence-based practice beliefs and implementation scales: Psychometric properties of two new instruments. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2008, 5, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarons, G.A. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The evidence-based practice attitude scale (EBPAS). Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2004, 6, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeun, E.J.; Kwon, Y.M.; Ahn, O.H. Development of a nursing professional value scale. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2005, 35, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985; pp. 1–416. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, H.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K. Nurses’ evidence-based practice beliefs and the role of evidence-based practice mentors at university hospitals in Finland. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2017, 14, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, H.L.; Ki, J.S. Clinical nurses’ beliefs, knowledge, organizational readiness and level of implementation of evidence-based practice: The first step to creating an evidence-based practice culture. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapri, N.D.; Ng, Y.T.; Wu, V.X.; Klainin-Yobas, P. Effectiveness of educational interventions on evidence-based practice for nurses in clinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 111, 105295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsillidou, M.; Roupa, Z.; Farmakas, A.; Noula, M. Barriers to the adoption of evidence-based practice among nurses. Kontakt 2020, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chays-Amania, A.; Schwingrouber, J.; Colson, S. Using implementation science to implement evidence-based practice: A discursive paper. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 0, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, C.; Ashcraft, A.; Long, J.; Cannon, S.; DiVito-Thomas, P.; Delaney, T. Self-efficacy: Changing the tide of evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2020, 17, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, T.; Ho, R.; Tang, A.; Tam, W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 123, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maljanian, R.; Caramanica, L.; Taylor, S.K.; MacRae, J.B.; Beland, D.K. Evidence-based nursing practice, part 2: Building skills through research roundtables. J. Nurs. Adm. 2002, 32, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Tan, A.; Hsieh, A.P.; Gallagher-Ford, L. Evidence-based practice culture and mentorship predict EBP implementation, nurse job satisfaction, and intent to stay: Support for the ARCC© model. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2021, 18, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strout, T. Curiosity and Reflective Thinking: Renewal of the Spirit; Sigma Theta Tau International: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dancot, J.; Pétré, B.; Voz, B.; Detroz, P.; Gagnayre, R.; Triffaux, J.M.; Guillaume, M. Self-esteem and learning dynamics in nursing students: An existential-phenomenological study. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raustøl, A.; Amsrud, K.E.; Skaug, E.A.; Lyberg, A.; Tveit, B. Nurses’ experiences with mentoring nursing students in nursing homes where an active, collaborative learning model Is introduced. A qualitative study. Nurs. Open 2024, 11, e70107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alatawi, M.; Aljuhani, E.; Alsufiany, F.; Aleid, K.; Rawah, R.; Aljanabi, S.; Banakhar, M. Barriers of implementing evidence-based practice in nursing profession: A literature review. Am. J. Nurs. 2020, 9, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Categories | Total (n = 30) | Experimental (n = 15) | Control (n = 15) | χ2 or t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) or | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Age (years) | <40 | 12(40.0) | 5(33.3) | 7(46.7) | 0.56 | 0.710 |

| ≥40 | 18(60.0) | 10(66.7) | 8(53.3) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 39.47 ± 5.43 | 40.53 ± 5.24 | 38.40 ± 5.58 | 1.08 | 0.289 | |

| Total working career (years) | <10 | 3(10.0) | 0(0) | 3(10.0) | 4.87 | 0.088 |

| ≥10~<20 | 17(56.7) | 11(73.3) | 6(20.0) | |||

| ≥20 | 10(33.3) | 4(26.7) | 6(20.0) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 16.60 ± 4.98 | 17.87 ± 4.69 | 15.33 ± 5.09 | 1.42 | 0.167 | |

| Work unit | Ward | 11(36.7) | 5(33.3) | 6(40.0) | 0.20 | 0.977 |

| ICU | 4(13.3) | 2(13.4) | 2(13.4) | |||

| Outpatient Department | 6(20.0) | 3(20.0) | 3(20.0) | |||

| Others | 9(30.0) | 5(33.3) | 4(26.6) | |||

| Period of postgraduate degree | ≤1 | 6(20.0) | 4(26.7) | 2(13.3) | 2.50 | 0.476 |

| >1~≤5 | 7(23.3) | 2(13.3) | 5(33.3) | |||

| >5~<10 | 10(33.4) | 6(40.0) | 4(26.7) | |||

| ≥10 | 7(23.3) | 3(20.0) | 4(26.7) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 3.69 ± 4.75 | 6.11 ± 5.38 | 6.47 ± 4.20 | −0.21 | 0.837 | |

| RPA | 3.29 ± 0.52 | 3.33 ± 0.51 | 3.25 ± 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.662 | |

| EBPB | 3.49 ± 0.422 | 3.49 ± 0.32 | 3.49 ± 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.979 | |

| EBPA | 3.97 ± 0.34 | 3.90 ± 0.36 | 4.04 ± 0.31 | −1.19 | 0.245 | |

| NPVS | 3.45 ± 0.60 | 3.57 ± 0.65 | 3.33 ± 0.55 | 1.10 | 0.281 | |

| Variables | Experimental Group (n = 15) | Control Group (n = 15) | Experimental vs. Control Groups | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test (M ± SD) | Post-Test (M ± SD) | t/Z (p) | ES (95% CI) | Pre-Test (M ± SD) | Post-Test (M ± SD) | t (p) | ES (95% CI) | Post-Test Only t (p) | ES (95% CI) | |

| RPA | 3.33 ± 0.51 | 3.83 ± 0.70 | −1.96 (0.050) | 0.82 0.07–1.56) | 3.25 ± 0.55 | 3.19 ± 0.54 | −0.36 (0.721) | −0.11 (−0.83–0.61) | −2.39 (0.016) | 1.02 (0.26–1.79) |

| EBPB | 3.49 ± 0.33 | 3.84 ± 0.46 | −3.30 (0.005) | 0.87 (0.13–1.62) | 3.49 ± 0.51 | 3.60 ± 0.47 | −1.29 (0.219) | 0.22 (−0.49–0.94) | 1.37 (0.180) | 0.52 (−0.21–1.24) |

| EBPA | 3.90 ± 0.36 | 4.00 ± 0.41 | −1.14 (0.275) | 0.26 (−0.46–0.98) | 4.04 ± 0.31 | 3.85 ± 0.25 | 1.54 (0.145) | −0.67 (−1.41–0.06) | 1.16 (0.256) | 0.44 (−0.28–1.17) |

| NPVS | 3.57 ± 0.65 | 3.78 ± 0.62 | −2.02 (0.063) | 0.33 (−0.39–1.05) | 3.33 ± 0.55 | 3.25 ± 0.60 | 0.69 (0.505) | −0.14 (−0.86–0.58) | 2.38 (0.024) | 0.87 (0.12–1.62) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.-A.; Jeong, H.-W. Effectiveness of the Research Practice Ability Enhancement Program on Evidence-Based Practice Competencies in Clinical Nurses: A Non-Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182273

Kim S-A, Jeong H-W. Effectiveness of the Research Practice Ability Enhancement Program on Evidence-Based Practice Competencies in Clinical Nurses: A Non-Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182273

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Sun-Ae, and Hye-Won Jeong. 2025. "Effectiveness of the Research Practice Ability Enhancement Program on Evidence-Based Practice Competencies in Clinical Nurses: A Non-Randomized Controlled Trial" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182273

APA StyleKim, S.-A., & Jeong, H.-W. (2025). Effectiveness of the Research Practice Ability Enhancement Program on Evidence-Based Practice Competencies in Clinical Nurses: A Non-Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare, 13(18), 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182273