Assessment of Endometriosis Knowledge and Its Determinants Among Nurses in Al-Jouf Region, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

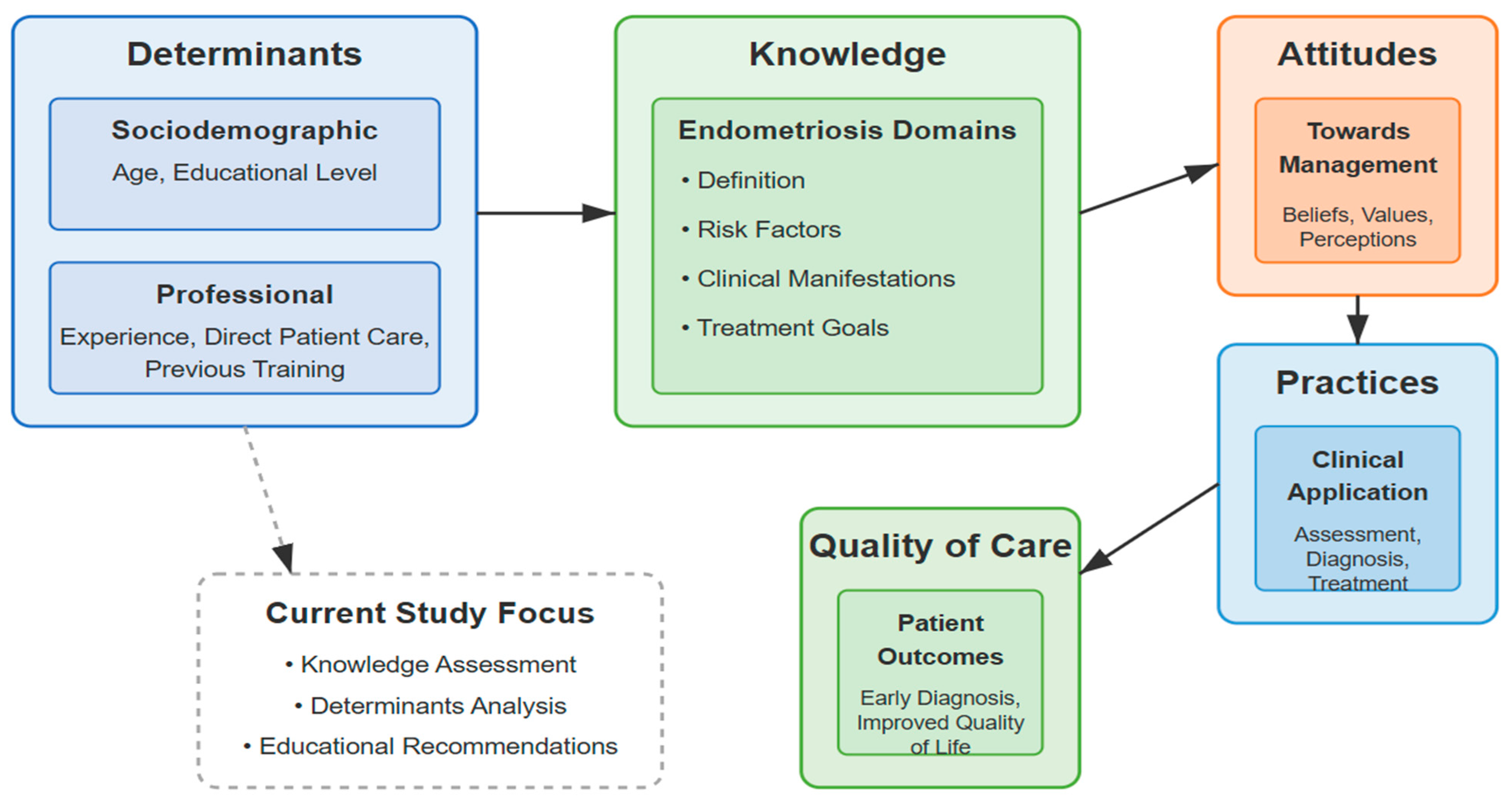

1. Introduction

- What are the levels of knowledge regarding endometriosis among nurses in Saudi Arabia?

- Is there an association between nurses’ sociodemographic characteristics, professional attributes, and level of knowledge about endometriosis?

- Which determinants, such as educational background, clinical experience, and workplace setting, significantly predict nurses’ knowledge levels regarding endometriosis?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Settings

2.3. Study Participants and Sample Size Determination

2.3.1. Variable Selection Strategy

2.3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Data Collection Tools

2.4.1. Instrument Overview

- -

- Low knowledge: <60% (0–11)

- -

- Moderate knowledge: 60–80% (12–16)

- -

- High knowledge: >80% (17–20)

2.4.2. Validation and Reliability Procedures

- I.

- Translation and Back-Translation:

- II.

- Expert Panel Review:

- III.

- Item Modifications:

- IV.

- Pilot Testing:

- V.

- Psychometric Evaluation:

- VI.

- Validity and reliability evidence.

2.5. Ethical Approval

2.6. Procedure

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Professional Characteristics of Study Participants

3.2. Knowledge Assessment Scores

3.3. Factors Associated with Knowledge Levels

3.4. Multivariate Analysis of Knowledge Determinants

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications, Future Directions, and Limitations

4.1.1. Practical Implications

4.1.2. Future Research Directions

4.1.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saunders, P.T.K.; Horne, A.W. Endometriosis: Etiology, Pathobiology, and Therapeutic Prospects. Cell 2021, 184, 2807–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwani, S.; Khan, M.W.A.; Rajendrasozhan, S.; Al-Motair, K.; Husain, Q.; Khan, W.A. The Vicious Cycle of Chronic Endometriosis and Depression—An Immunological and Physiological Perspective. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1425691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessoa De Farias Rodrigues, M.; Pessoa De Farias Rodrigues, M.; Lima Vilarino, F.; De Souza Barbeiro Munhoz, A.; Da Silva Paiva, L.; Da Silva Paiva, L.; De Alcantara Sousa, L.V.; De Alcantara Sousa, L.V.; Zaia, V.; Parente Barbosa, C.; et al. Clinical Aspects and the Quality of Life among Women with Endometriosis and Infertility: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warzecha, D.; Szymusik, I.; Wielgos, M.; Pietrzak, B. The Impact of Endometriosis on the Quality of Life and the Incidence of Depression—A Cohort Study. Int. J. Envrion. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozati, R.; Tabasum, W.; Ahmed, M.S.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmed, T.N.; Nayela, S.; Azimi, S.S. Prevalence, Surgical, and Medical Management of Patients with Endometriosis amongst Indian Women. Eur. J. Med. Health Sci. 2023, 5, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, Y.; Shams-Beyranvand, M.; Khateri, S.; Gharahjeh, S.; Tehrani, S.; Varse, F.; Tiyuri, A.; Najmi, Z. A Systematic Review on the Prevalence of Endometriosis in Women. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2021, 154, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K.; Munro, D.; Clarke, J. Endometriosis Is Undervalued: A Call to Action. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2022, 3, 902371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harzif, A.K.; Nurbaeti, P.; Sayogo Putri, A.; Silvana, V.; Andyra, A.F.; Wiweko, B. Factors Associated with Delayed Diagnosis of Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain. Disord. 2024, 22840265241291120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homepage, J.; Yuspa, R.; Author, C. Economic Burden of Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asian J. Health Res. 2024, 3, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.N.; Amaral, K.V. The Role of Nursing in the Care of Patients with Pain Due to Endometrios: A Literature Review. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e144101421952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remes, A.; Hakala, M.; Oikarinen, A. Endometriosis Patients’ Experiences of the Counseling They Need from the Nurses through the Digital Care Pathway: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Nord. J. Nurs. Res. 2023, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeler, E.; Fantasia, H.C.; Morse, B.L. Interventions and Practice Implications for the Management of Endometriosis. Nurs. Womens Health 2020, 24, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.R.; Ross, J.A.; Smith, D.P. KOREA: Trends in Four National KAP Surveys, 1964–1967. Stud. Fam. Plann 1969, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, P.G.; Lawless, K.A. The Knowledge, Attitudes, & Behaviors Approach How to Evaluate Performance and Learning in Complex Environments. Perform. Improv. 2004, 43, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xu, Q.; Long, M.; Zheng, Y.; Li, L.; Niu, C. University Students’ Fertility Awareness and Its Influencing Factors: A Systematic Review. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad Messawa, M.; Yousef Omar, S.; Babagi, R.A. Endometriosis in Saudi Arabia; Prevalence, Presentation, Complications, and Updated Management: Simple Systematic Review. Int. J. Pharm. Phytopharm. Res. 2020, 10, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, C.; Thatcher, J.B.; Grover, V.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Cross-Sectional Research: A Critical Perspective, Use Cases, and Recommendations for IS Research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 70, 102625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE Guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggarth, P.A.; Innes, C.R.H.; Dalrymple-Alford, J.C.; Jones, R.D. Prediction of Driving Ability: Are We Building Valid Models? Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 77, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdfelder, E.; FAul, F.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlorke, S. The Aquila Digital Community The Aquila Digital Community Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Knowledge of Endometriosis: A Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Knowledge of Endometriosis: A Pilot Study Pilot Study. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, B.S.; Engelhart, M.D.; Furst, E.J.; Hill, W.H.; Krathwohl, D.R. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. In Handbook I: Cognitive Domain; David McKay Company: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, A.M.; Risoer, M.B.; Forman, A.; Seibaek, L. Practices and Attitudes Concerning Endometriosis Among Nurses Specializing in Gynecology. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2016, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, R.V.; Boyd, K.M.; Webb, D.J. The Revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: Past, Present and Future. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 57, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the Quality of Web Surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 2004, 6, e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. Empirical Analysis of Decision Making of an AI Agent on IBM’s 5Q Quantum Computer. Nat. Sci. 2018, 10, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Roullier, C.; Sanguin, S.; Parent, C.; Lombart, M.; Sergent, F.; Foulon, A. General Practitioners and Endometriosis: Level of Knowledge and the Impact of Training. J. Gynecol. Obs. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 102227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heena, H.; Durrani, S.; Alfayyad, I.; Riaz, M.; Tabasim, R.; Parvez, G.; Abu-Shaheen, A. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices towards Cervical Cancer and Screening amongst Female Healthcare Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 5423130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.; Rafiq, A.; Jamil, A.; Sarfraz, Z.; Sarfraz, A.; Robles-Velasco, K.; Cherrez-Ojeda, I. Addressing the Endometriosis Knowledge Gap for Improved Clinical Care—A Cross-Sectional Pre- and Post-Educational-Intervention Study among Pakistani Women. Healthcare 2023, 11, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.K.; Chapron, C.; Giudice, L.C.; Laufer, M.R.; Leyland, N.; Missmer, S.A.; Singh, S.S.; Taylor, H.S. Clinical Diagnosis of Endometriosis: A Call to Action. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2019, 220, e1–e354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.K.; Javadzadeh, A.; Hasankhani, H.; Parizad, Z.A. Relationship between Learning Styles and Clinical Competency in Nursing Students. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyel, D.; Boyd, J.H.; Graham, M. Informational Support for Women with Endometriosis: A Scoping Review. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundström, H.; Alehagen, S.; Kjølhede, P.; Berterö, C. The Double-Edged Experience of Healthcare Encounters among Women with Endometriosis: A Qualitative Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, I.V.; Kleisiaris, C.F.; Fradelos, E.C.; Kakou, K.; Kourkouta, L. Critical Thinking: The Development of an Essential Skill for Nursing Students. Acta Inform. Medica 2014, 22, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuspita, F.C.; Sukartini, T.; Ahsan, A.; Nursalam, N.; Hastuti, A.P. Clinical Achievement Improvement through Experiential Learning-Based Training. Healthc. Low. Resour. Settings 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal Helmy, H.; Mohamed Magdi Fakhreldin Mohamed, H.; El -Sayed Ibrahim, R. Effect of Nursing Program Regarding Lifestyle Modification on Selected Outcomes among Women with Endometriosis. Egypt. J. Health Care 2021, 12, 1396–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namazi, M.; Behboodi Moghadam, Z.; Zareiyan, A.; Jafarabadi, M. Exploring the Impact of Endometriosis on Women’s Lives: A Qualitative Study in Iran. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 1275–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandi, N.; Behboodi Moghadam, Z.; Hossein Rashidi, B.; Namazi, M.; Haghani, S. Reproductive Health of Women with Endometriosis: An Improving Educational Intervention Based on the Planned Behavior Theory. Middle East. Fertil. Soc. J. 2023, 28, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, M.Ö.; Wikberg, C.; Björkelund, C.; Ariai, N.; Lindahl, A.-C.; Hange, D. Laying the Groundwork: A Pilot Study Exploring Improved Endometriosis Management Strategies in Primary Healthcare. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, 17, 1325–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, L.; Bhattacharya, S. Measuring What Matters-A Holistic Approach to Measuring Well-Being in Endometriosis. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2021, 2, 770366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K.; Meador, A.; Ponnampalam, A.; Wood, R. Survey of General Practitioner Perspectives on Endometriosis Diagnosis, Referrals, Management and Guidelines in New Zealand. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazan, Z.; Mroueh, F.; Hazime, Z.; Joumaa, S.; Hamze, K.; Husseini, A.; Mansour, S.; Hoballah, A.; El Haidari, R. Knowledge and Concern towards Endometriosis among Lebanese Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Women’s Health 2024, 24, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, M.; Al-Jefout, M.; Alsafar, H.; Kirtley, S.; Lindgren, C.M.; Missmer, S.A.; Becker, C.M.; Zondervan, K.T.; Rahmioglu, N. Prevalence of Common Gynecological Conditions in the Middle East: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Reprod. Health 2021, 3, 661360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickett, C.; Foster, W.G.; Agarwal, S.K. Current Endometriosis Care and Opportunities for Improvement. Reprod. Fertil. 2023, 4, e220091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Perucha, L.; Pistillo, A.; Raventós, B.; Jacques-Aviñó, C.; Munrós-Feliu, J.; Martínez-Bueno, C.; Valls-Llobet, C.; Carmona, F.; López-Jiménez, T.; Pujolar-Díaz, G.; et al. Endometriosis Prevalence and Incidence Trends in a Large Population-Based Study in Catalonia (Spain) from 2009 to 2018. Women’s Health 2022, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.I. Effect of Guideline about Endometriosis on Enhancing Young Female Knowledge and Utilization of Health Services. Int. J. Nov. Res. Healthc. Nurs. 2018, 5, 360–370. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jefout, M.; Alnawaiseh, N.; Yaghi, S.; Alqaisi, A. Prevalence of Endometriosis and Its Symptoms among Young Jordanian Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain Refractory to Conventional Therapy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2018, 40, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdo, N.M.; Ahmad, H.; Loney, T.; Zarmakoupis, P.N.; Aslam, I.; Irfan, S.; Grivna, M.; Ahmed, L.A.; Al-Rifai, R.H. Characterization of Fertility Clinic Attendees in the Abu Dhabi Emirate, United Arab Emirates: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnuaimi, A.S.; Syed, M.A.; Zainel, A.A.; Mohamed, H.A.; Bougmiza, M.I.; Syed, M.A. Cultural & Region-Specific Adaptation of KAP (Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice) Tool to Capture Healthy Lifestyle within Primary Care Settings. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.; Menon, V.; Ameen, S.; Kumar Praharaj, S. Designing and Conducting Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Surveys in Psychiatry: Practical Guidance. Indian. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyad, A.; Baker, N.A.; Oweidat, I.; Al-Mugheed, K.; Alsenany, S.A.; Abdelaliem, S.M.F. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices toward Patient Safety among Nurses in Health Centers. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukourikos, K.; Tsaloglidou, A.; Kourkouta, L.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Iliadis, C.; Fratzana, A.; Panagiotou, A. Simulation in Clinical Nursing Education. Acta Inform. Medica 2021, 29, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArthur, C.; Bai, Y.; Hewston, P.; Giangregorio, L.; Straus, S.; Papaioannou, A. Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing Evidence-Based Guidelines in Long-Term Care: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Implement. Sci. 2021, 16, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, H.; Lewis, M.; Ng, C.H.M.; Brooks, C.; Leonardi, M.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; Bush, D.; Semprini, A.; Wilkinson-Tomey, J.; Condous, G.; et al. Social Media, Endometriosis, and Evidence-Based Information: An Analysis of Instagram Content. Healthcare 2024, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, S.G.; Angioni, S.; Saponara, S.; Sicilia, G.; Etrusco, A.; D’Alterio, M.N.; Cobellis, L.; De Franciscis, P.; Riemma, G. TikTok as a Platform for Hysteroscopy Information: An Analytical Video-Based Cross-Sectional Study to Assess Quality, Reliability, and Accuracy. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 168, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J.; Beck, C.T.; Polit, D.F. Polit and Beck’s Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2025; ISBN 9781975223809. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 366616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n | % (95% CI) * |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) a | ||

| ≤30 | 101 | 47.0 (40.3–53.7) |

| 31–40 | 75 | 34.9 (28.8–41.6) |

| 40–50 | 31 | 14.4 (10.1–19.7) |

| >50 | 8 | 3.7 (1.6–7.1) |

| Educational Level | ||

| Diploma | 69 | 32.1 (26.1–38.6) |

| Bachelor’s or higher + | 146 | 67.9 (61.4–73.9) |

| Years of Experience | ||

| <5 | 47 | 21.9 (16.7–27.9) |

| 5–10 | 97 | 45.1 (38.4–51.8) |

| >10 | 71 | 33.0 (27.0–39.5) |

| Previous Endometriosis Training | ||

| Yes | 56 | 26.0 (20.5–32.1) |

| No | 159 | 74.0 (67.9–79.5) |

| Direct Patient Care Experience with Endometriosis | ||

| Yes | 23 | 10.7 (7.0–15.5) |

| No | 192 | 89.3 (84.5–93.0) |

| Characteristic | Total Sample n (%) | Satisfactory n (% of 84) | Unsatisfactory n (% of 131) | χ2 | p-Value | Cramer’s V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 11.175 | 0.011 | 0.228 | |||

| ≤30 | 101 (47.0) | 28 (33.3) | 73 (55.7) | |||

| 31–40 | 75 (34.9) | 35 (41.7) | 40 (30.5) | |||

| 41–50 | 31 (14.4) | 16 (19.0) | 15 (11.5) | |||

| >50 | 8 (3.7) | 5 (6.0) | 3 (2.3) | |||

| Educational Level | 39.942 | <0.001 | 0.431 | |||

| Diploma | 69 (32.1) | 8 (9.5) | 61 (46.6) | |||

| Bachelor’s/Master’s | 146 (67.9) | 76 (90.5) | 70 (53.4) | |||

| Years of Experience | 11.579 | 0.003 | 0.232 | |||

| <5 years | 47 (21.9) | 13 (15.5) | 34 (26.0) | |||

| 5–10 years | 97 (45.1) | 32 (38.1) | 65 (49.6) | |||

| >10 years | 71 (33.0) | 39 (46.4) | 32 (24.4) | |||

| Direct Patient Care with Endometriosis | 16.618 | <0.001 | 0.278 | |||

| Yes | 23 (10.7) | 18 (21.4) | 5 (3.8) | |||

| No | 192 (89.3) | 66 (78.6) | 126 (96.2) | |||

| Previous Endometriosis Training | 6.689 | 0.010 | 0.176 | |||

| Yes | 56 (26.0) | 30 (35.7) | 26 (19.8) | |||

| No | 159 (74.0) | 54 (64.3) | 105 (80.2) |

| Knowledge Domain | Educational Level | Years of Experience |

|---|---|---|

| Definition of Endometriosis (0–2) ~ | p < 0.001 * | p = 0.037 * |

| - Low (reference) | 0.82 ± 0.48 ‡ | 0.79 ± 0.45 ‡ |

| - High | 1.24 ± 0.52 ** | 1.31 ± 0.49 ** |

| Risk Factors (0–4) ~ | p < 0.001 * | p = 0.042 * |

| - Low (reference) | 1.85 ± 0.92 ‡ | 1.78 ± 0.89 ‡ |

| - High | 2.46 ± 0.97 ** | 2.52 ± 0.95 ** |

| Clinical Manifestations (0–10) ~ | p < 0.001 * | p = 0.028 * |

| - Low (reference) | 5.92 ± 1.68 ‡ | 5.85 ± 1.72 ‡ |

| - High | 7.34 ± 1.75 ** | 7.48 ± 1.70 ** |

| Treatment Goals (0–4) ~ | p < 0.001 * | p = 0.035 * |

| - Low (reference) | 1.95 ± 0.82 ‡ | 1.88 ± 0.85 ‡ |

| - High | 2.48 ± 0.89 ** | 2.56 ± 0.87 ** |

| Total Knowledge Score (0–20) ~ | p < 0.001 * | p = 0.031 * |

| - Low (reference) | 10.54 ± 2.93 ‡ | 10.30 ± 2.89 ‡ |

| - High | 13.87 ± 3.15 ** | 13.87 ± 3.08 |

| Predictor Variables | B | SE | β | VIF | t | p-Value | 95% CI | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 42.156 | 2.431 | - | - | 17.341 | <0.001 | 37.365, 46.947 | - |

| Age (years) | 3.106 | 0.798 | 0.232 | 1.45 | 3.894 | <0.001 | 1.534, 4.679 | 0.089 |

| Educational Level (ref: Diploma) | ||||||||

| Bachelor’s or Higher | 9.769 | 1.353 | 0.415 | 1.32 | 7.223 | <0.001 | 7.103, 12.435 | 0.176 |

| Experience (Years) | 1.871 | 0.910 | 0.149 | 1.38 | 2.057 | 0.041 | 0.078, 3.665 | 0.042 |

| Direct Patient Care 1 | 5.008 | 2.154 | 0.168 | 1.21 | 2.325 | 0.021 | 0.762, 9.254 | 0.051 |

| Previous Training 2 | 1.327 | 1.490 | 0.056 | 1.18 | 0.890 | 0.374 | −4.265, 1.611 | 0.008 |

| Predictor Variables | B | SE | Wald χ2 | p-Value | aOR | 95% CI | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | −0.319 | 0.195 | 2.667 | 0.103 | 0.727 | 0.495, 1.066 | 1.42 |

| Educational Level 1 | −1.897 | 0.419 | 20.524 | <0.001 | 0.150 | 0.066, 0.342 | 1.35 |

| Years of Experience | −0.408 | 0.226 | 3.258 | 0.071 | 0.665 | 0.427, 1.035 | 1.38 |

| Direct Patient Care 2 | −1.419 | 0.566 | 6.284 | 0.012 | 0.242 | 0.080, 0.734 | 1.24 |

| Previous Training 3 | −0.581 | 0.365 | 2.537 | 0.111 | 0.559 | 0.273, 1.143 | 1.19 |

| Constant | 2.865 | 0.451 | 40.326 | <0.001 | 17.549 | - | - |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Demographics | |||

| - Age | 0.232 (0.124, 0.340) ** | 0.185 (0.077, 0.293) * | 0.168 (0.060, 0.276) * |

| Step 2: Educational Background | |||

| - Educational Level | - | 0.415 (0.307, 0.523) *** | 0.382 (0.274, 0.490) *** |

| - Years of Experience | - | 0.149 (0.041, 0.257) * | 0.135 (0.027, 0.243) * |

| Step 3: Professional Exposure | |||

| - Direct Patient Care | - | - | 0.168 (0.060, 0.276) * |

| - Previous Training | - | - | 0.056 (−0.052, 0.164) |

| Model Statistics | |||

| - R2 | 0.124 | 0.298 | 0.376 |

| - ΔR2 | 0.124 | 0.174 | 0.078 |

| - F for ΔR2 | 15.012 *** | 25.845 *** | 12.654 *** |

| - Adjusted R2 | 0.116 | 0.285 | 0.361 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elsharkawy, N.B.; Alshammari, A.M.; Ramadan, O.M.E.; Abdelaziz, E.M.; Elzeky, M.E.H.; Hafiz, A.H.; Alrowily, M.F.; Alruwaili, S.M.; Abo-Seif, L.M.E.-S. Assessment of Endometriosis Knowledge and Its Determinants Among Nurses in Al-Jouf Region, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1386. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121386

Elsharkawy NB, Alshammari AM, Ramadan OME, Abdelaziz EM, Elzeky MEH, Hafiz AH, Alrowily MF, Alruwaili SM, Abo-Seif LME-S. Assessment of Endometriosis Knowledge and Its Determinants Among Nurses in Al-Jouf Region, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. 2025; 13(12):1386. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121386

Chicago/Turabian StyleElsharkawy, Nadia Bassuoni, Afrah Madyan Alshammari, Osama Mohamed Elsayed Ramadan, Enas Mahrous Abdelaziz, Mohamed E. H. Elzeky, Alaa Hussain Hafiz, Mary Faleh Alrowily, Sultan Muharib Alruwaili, and Lareen Magdi El-Sayed Abo-Seif. 2025. "Assessment of Endometriosis Knowledge and Its Determinants Among Nurses in Al-Jouf Region, Saudi Arabia" Healthcare 13, no. 12: 1386. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121386

APA StyleElsharkawy, N. B., Alshammari, A. M., Ramadan, O. M. E., Abdelaziz, E. M., Elzeky, M. E. H., Hafiz, A. H., Alrowily, M. F., Alruwaili, S. M., & Abo-Seif, L. M. E.-S. (2025). Assessment of Endometriosis Knowledge and Its Determinants Among Nurses in Al-Jouf Region, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare, 13(12), 1386. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121386