Stakeholders’ Roles and Views in the Provision of Sexually Transmitted Infection Services Among Key and Priority Populations in Limpopo Province, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting

2.3. Sampling and Data Collection

2.3.1. Sampling

2.3.2. Data Collection and Recruitment

Recruitment

2.3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Data Management

2.6. Validity, Reliability, and Trustworthiness

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the STI Stakeholders

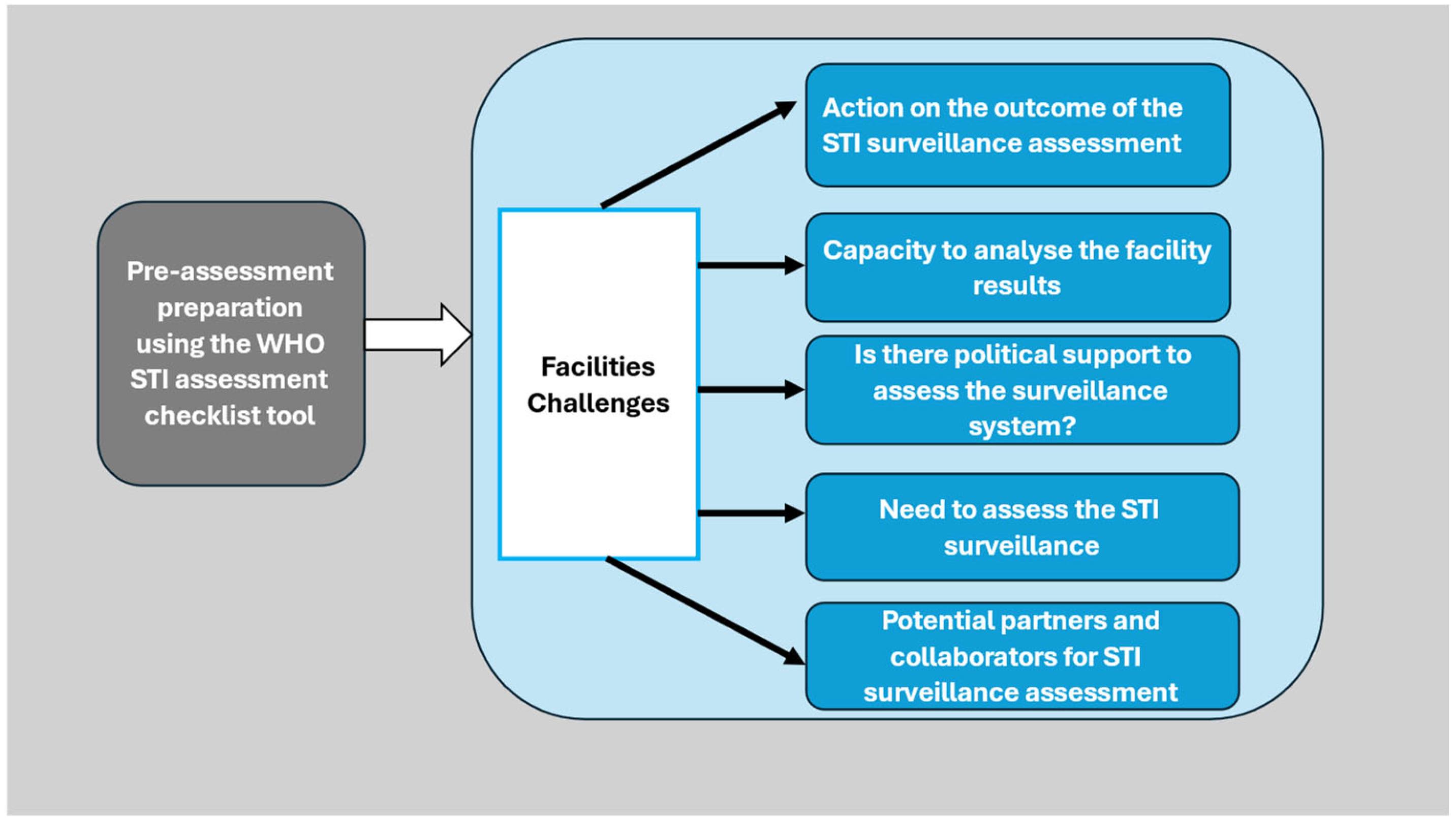

3.2. Pre-Assessment Preparation Using the WHO STI Assessment Checklist Tool

“Yes, the government came to our clinic and did the assessment, but it would end there. We will never hear from them again.”(P5, Female, Facility Manager, 51 years).

“We report our daily cases on our clinic register. Do you know what we do? At a PHC facility level, we just compile monthly summary statistics and send them to the district. For example, we compiled statistics to show how many cases there were this month. However, the report will be analysed at the district level and not by the facility.”(P8, Female, Professional nurse, 48 years old).

‘No, I think all that we want now is a political buy-in and also a multi-sectoral approach and support for STI programme assessment in PHC facilities.’(P18, Female Deputy Director for STIs and key population, 51 years old).

’Yes, there is a big need because STIs are not prioritised as HIV; when HIV was still a pandemic, they used to talk about it together with other STIs. Now that HIV is manageable with treatment, they are no longer talking about it. They only talk about STI when they see their prevalence increasing.’(P5, Female, Facility Manager, 51 years old).

‘We have implementing partners such as the WHO, the University of Witwatersrand Reproductive Health and HIV Institute (WITS RHI), the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD), the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA) and the South African universities with which we work closely to improve the STI surveillance. These institutions assist in facilitating early diagnosis, which prompts treatment and disease surveillance in the country.’(P 17, Female, Laboratory Manager, 51 years old).

3.3. Stakeholders’ Views on STI Service Provision Among Key and Priority Populations

“We treat patients with three medicines: azithromycin, ceftriaxone, and metronidazole. For genital discharge (GD) such as vaginal discharge syndrome (VDS), NG (drop), MUS, metronidazole tablets 2 g single dose, 250 mg ceftriaxone injectable, and 1 g of azithromycin single dose are used. For syphilis, we give them benzylpenicillin injectable 2.4 mu once weekly for three weeks.”(P12, Female, Facility Manager, 53 years old).

“We use a rapid test kit to test for HIV/syphilis, and we screen for cervical cancer as well as MUS.”(P13, Female, Clinical Nurse Practitioner, 64).

“We do not do counselling separately from our PHC services; the person is counselled before being tested. We also provide health education; we encourage our patients to use condoms consistently and undergo regular pap smear.”(P2, Female, Professional Nurse, 35 years old).

“We do regular in-service training in the facility. This can occur on a daily basis if one of the sister nurses finds new information, attends a workshop, or there is a new guideline, and we share it with others or amongst ourselves.”(P7, Female, Professional Nurse, 34 years old; P12, Female, Facility Manager, 50 years old).

“We report STI cases monthly; we use the registers and the system (e-tick register) to check the monthly STI average. For the completeness of the data, we use patients’ files, clinic registers, and electronic systems, checking, validating, and comparing if everything from the patients’ files and registers tallies with what is on the e-tick register.”(P9, Female, Facility Manager, 50 years old).

“All our services are available for 24 h, and our clinic operates from Monday to Sunday.”(P3, Male, Facility Manager, 58 years old; P5, Female, Facility Manager, 53 years old).

“Treatment for STIs is always available. For example, for ANC, we have a new test kit called a rapid test, an HIV/STI test kit. We can also withdraw blood and send it to the laboratory, and get the lab results after 72 h. The National Health Laboratory Services (NHLS) Courier guy collects blood samples or specimens daily.”(P13, Female, Clinical Nurse Practitioner, 64 years old).

“We have a microbiology laboratory with molecular techniques to detect all the different types of pathogens causing any STI syndromes and perform the serological tests. We have our in-house assay, a multiplex PCR, Ribonucleic Acid (RNA) based, Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) based methods and some commercial kits that we use to verify or confirm results.”(P16, Female, Epidemiologist, 47 years old; P17, Female, Lab Manager, 51 years old).

“We use a triage strategy; we start with patients who are very sick, then minor ailments (minor illnesses and injuries), followed by babies and children.”(P8, Professional Nurse, Female, 48 years old).

“We give three drugs for treatment. Sometimes, you may discover that one of the drugs is unavailable, so we outsource from nearby clinics. There is a point at which, as clinics, we exchange and request medication from other clinics.”(P7, Female, Professional Nurse, 34 years old).

“All the services in public facilities are free of charge.”(P17, Female Lab Manager, 51 years old; P19, Female STI and key populations Director, 55 years old).

“We provide individual health education in consultation rooms. We also provide group sessions, covering important topics such as how STIs are transmitted, how they can be treated, and the best ways to prevent them.”(P7, Female, Professional Nurse, 34 years old).

“We have peer councillors and home-based carers who conduct campaigns or STI drives mainly targeting the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, and queer (LGBTQ) community, where condoms and healthcare services are distributed. These services are also available to everyone in the community, including within taverns, schools, and universities.”(P7, Female, Professional Nurse, 34 years old; P11, Female, Clinical Nurse Practitioner, 50).

“We follow our clients physically using phones and through CHWs. When CHWs go to the field, they come across other patients who, along the way, did not complete their prescribed medication courses. The CHWs will bring the patient back to the clinic, where they will be given medication again.”(P7, Female, Professional Nurse, 34 years old).

“We do outreach activities or awareness programmes using various platforms such as Facebook.”(P12, Female, Facility Manager, 53 years old).

“When the patient comes to the clinic having a headache, for example, we screen for all the diseases. We do not treat STI as an isolated disease.” “We have integrated STI services with chronic, acute, family planning, HIV and pregnancy, TB, sexual reproductive health, ANC, Mother and Child Health, and Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission.” (PMCT).(P1, Female, Professional Nurse, 60 years old; P18: Female, Director of STI and key populations, 55 years old).

“We have a successful rate of treatment, which is 95% available, health education, and the provision of condoms, necessary guidelines to facilitate this service, and we are available 24 h.”(P5, Female, Facility Manager, 51 years old).

“I do not know how to explain the staffing issue because, according to Workload Indicators of Staffing Needs (WISN), we are enough in this facility, and they allocated staff according to our patients’ headcounts. Our data still says we are okay and do not need more staff members. In reality, according to my view, I will say there is a shortage of staff despite the use of the WISN technique.”(P12, Female, Facility Manager, 53 years old).

“Yes, sometimes we are told there is no budget for advanced machines. We always require more staff, more equipment, and more reagents. Sometimes, we run out of reagents.”(P17, Female, Lab Manager, 51 years old).

“We do not have advanced equipment for testing STIs within PHC facilities; we have a syphilis rapid test. For other STIs, we use the syndromic management approach.”(P1, Female, Professional Nurse, 60 years old).

“We have challenges with missing files in this facility. You might find that one person ends up having two to three different files, and in this way, we cannot track the client’s medical problem or history.”(P4, Female, Professional Nurse, 39 years old).

“Some of our patients are ignorant, while others cannot adapt and correct their lifestyles. They do not use condoms, have multiple partners, and they re-contact STIs and get re-infected.”(P14, Female, Professional Nurse, 30 years old).

“The STI-positive clients do not refer their husbands or sexual partners for treatment to the clinic.”(P15, Female, Facility Manager, 31 years old).

“Our patients primarily rely on social media and Google to self-diagnose. When we provide treatment to such patients, they combine it with medication from the pharmacies, which often leads to a high rate of treatment failure.”(P4, Female, Facility Manager, 51 years old).

“Patients tend to give us wrong addresses and numbers; therefore, this makes it difficult to trace them.”(P13, Female, Professional Nurse, 64 years old).

4. Discussion

Pre-Assessment Using the WHO STI Checklist Tool

5. Limitations and Strengths of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANC | Antenatal care |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| ART | Antiretroviral treatment |

| CHWs | Community Health Workers |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| GD | Genital discharge |

| HCW | Healthcare workers |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| KPP | Key and priority populations |

| LGBTQ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning |

| LP | Limpopo Province |

| MUS | Male urethritis syndrome |

| MSM | Men who have sex with men |

| MPH | Master of Public Health |

| NICD | National Institute for Communicable Diseases |

| NG | Neisseria gonorrhoea |

| NHLS | National Health Laboratory Services |

| NSP | National Strategic Plan |

| OPD | Outpatient department |

| PACER | Pan African Centre for Epidemic |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PHC | Primary healthcare |

| PhD | Doctor of Philosophy |

| PMCT | Mother and Child Health and Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission |

| PN | Partner notification |

| REC | Research Ethics Committee |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| SAMRC | South African Medical Research Council |

| SASA | South African Triage Scale |

| STIs | Sexually transmitted infections |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| VMMC | Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision |

| VDS | Vaginal discharge syndrome |

| UJ | University of Johannesburg |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| WISN | Workload Indicators of Staffing Needs |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategies on, Respectively, HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections for the Period 2022–2030. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240053779 (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- National Strategic Plan, 2023–2028: Addressing Barriers to Accessing Health and Social Services. Journalism for Public Health. 2023. Available online: https://sanac.org.za/national-strategic-plan-2023-2028/ (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV, Viral Hepatitis and STI Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations. Geneva. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240052390 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Kularatne, R.; Maseko, V.; Mahlangu, P.; Muller, E.; Kufa, T. Etiological surveillance of male urethritis syndrome in South Africa: 2019 to 2020. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2022, 49, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, B.D.; Sekgele, W.; Nhlapo, D.; Mahlangu, M.P.; Venter, J.M.; Maseko, D.V.; Müller, E.E.; Greeves, M.; Botha, P.; Radebe, F.; et al. Extragenital Sexually Transmitted Infections Among High-Risk Men Who Have Sex with Men in Johannesburg, South Africa. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2024, 51, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Sanchez, T.H.; Dominguez, K.; Bekker, L.G.; Phaswana-Mafuya, N.; Baral, S.D.; McNaghten, A.D.; Kgatitswe, L.B.; Valencia, R.; Yah, C.S.; et al. Sexually transmitted infection screening, prevalence and incidence among South African men and transgender women who have sex with men enrolled in a combination HIV prevention cohort study: The Sibanye Methods for Prevention Packages Programme (MP3) project. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020, 23 (Suppl. 6), e25594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harryparsad, R.; Meyer, B.; Taku, O.; Serrano, M.; Chen, P.L.; Gao, X.; Williamson, A.L.; Mehou-Loko, C.; d’Hellencourt, F.L.; Smit, J.; et al. Prevalence and incidence of sexually transmitted infections among South African women initiating injectable and long-acting contraceptives. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufa-Chakezha, T.; Shangase, N.; Singh, B.; Cutler, E.; Aitken, S.; Cheyip, M.; Ayew, K.; Lombard, C.; Manda, S.; Puren, A. The 2022 Antenatal HIV Sentinel Survey: Key Findings. 2022. Available online: https://www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Antenatal-survey-2022-report_National_Provincial_12Jul2023_Clean_01.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Geneva: World Health Organization. Updated Recommendations for the Treatment of Neisseria Gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Treponema pallidum (syphilis), and New Recommendations on Syphilis Testing and Partner Services. 2024. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/378213/9789240090767-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Chabata, S.T.; Fearon, E.; Musemburi, S.; Machingura, F.; Machiha, A.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Ndowa, F.J.; Mugurungi, O.; Cowan, F.M.; Steen, R. High Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Infections and Poor Sensitivity and Specificity of Screening Algorithms for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea Among Female Sex Workers in Zimbabwe: Analysis of Respondent-Driven Sampling Surveys in 3 Communities. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2025, 52, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. Health. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.za/about-sa/health (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- World Health Organization. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis) (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Management of Symptomatic Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240024168 (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Chesang, K.; Hornston, S.; Muhenje, O.; Saliku, T.; Mirjahangir, J.; Viitanen, A.; Musyoki, H.; Awuor, C.; Githuka, G.; Bock, N. Healthcare provider perspectives on managing sexually transmitted infections in HIV care settings in Kenya: A qualitative thematic analysis. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaya, Z.N.; Mapanga, W.; Moetlhoa, B.; Mashamba-Thompson, T.P. Nurses’ perspectives on user-friendly self-sampling interventions for diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections among young women in eThekwini district municipality: A nominal group technique. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makura, C. Landscape Analysis Report on Sexually Transmitted Infections Prevention, Treatment and Management Strategies in Zimbabwe. 2023. Available online: https://avac.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/PZAT_STI-Landscape-analysis-presentation_.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- World Health Organisation. The Diagnostics Landscape for Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240077126 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Seloka, M.A.; Phalane, E.; Phaswana-Mafuya, R.N. Evaluation of the sexually transmitted infections programme among key and priority populations in primary healthcare facilities to inform a targeted response: A protocol paper. MPs J. 2024, 7, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Klar, S.; Leeper, T.J. Identities and intersectionality: A case for Purposive sampling in Survey-Experimental Research. In Experimental Methods In Survey Research: Techniques That Combine Random Sampling with Random Assignment; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 15, pp. 419–433. [Google Scholar]

- Blaauw, D.; Ditlopo, P.; Rispel, L.C. Nursing education reform in South Africa—Lessons from a policy analysis study. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 26401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxim, L.D.; Niebo, R.; Utell, M.J. Screening tests: A review with examples. Inhal. Toxicol. 2014, 26, 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. A Tool for Strengthening STI Surveillance at the Country Level; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/161074 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.K. How to choose a sampling technique and determine sample size for research: A simplified guide for researchers. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 12, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri, R.; Ofoghi, S. Trustworth and rigor in qualitative research. Int. J. Adv. Biotechnol. Res. 2016, 7, 1914–1922. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, N.A.; King, J.R. Expanding approaches for research: Understanding and using trustworthiness in qualitative research. J. Dev. Educ. 2020, 44, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Garrib, A.; Stoops, N.; McKenzie, A.; Dlamini, L.; Govender, T.; Rohde, J.; Herbst, K. An evaluation of the District Health Information System in rural South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2008, 98, 549–552. [Google Scholar]

- Seloka, M.A.; Phalane, E.; Phaswana-Mafuya, R.N. The control and prevention of sexually transmitted infections in primary healthcare facilities among key and priority populations in sub-Saharan Africa. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2025, 29, 168–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarron, E.; Wynn, R. Use of social media for sexual health promotion: A scoping review. Glob. Health Action 2016, 9, 32193. [Google Scholar]

- Young, S.D.; Harrell, L.; Jaganath, D.; Cohen, A.C.; Shoptaw, S. Feasibility of recruiting peer educators for an online social networking-based health intervention. Health Educ. J. 2013, 72, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cometto, G.; Ford, N.; Pfaffman-Zambruni, J.; Akl, E.A.; Lehmann, U.; McPake, B.; Ballard, M.; Kok, M.; Najafizada, M.; Olaniran, A.; et al. Health policy and system support to optimise community health worker programmes: An abridged WHO guideline. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1397–e1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masinga, L. City of Johannesburg Demonstrated that Extending Clinics’ Operating Hours Reduces Hospital Overcrowding and Improves the Accessibility of Healthcare Services for Diverse Population Groups. 2016. Available online: https://iol.co.za/news/south-africa/gauteng/2017-04-03-city-of-johannesburg-spends-r7-million-on-extending-clinic-hours/ (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Dixon, J.; Burkholder, T.; Pigoga, J.; Lee, M.; Moodley, K.; de Vries, S.; Wallis, L.; Mould-Millman, N.K. Using the South African Triage Scale for prehospital triage: A qualitative study. BMC Emerg. Med. 2021, 21, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegeli, C.; Fraze, J.; Wendel, K.; Burnside, H.; Rietmeijer, C.A.; Finkenbinder, A.; Taylor, K.; Devine, S. Predicting clinical practice change: An evaluation of trainings on sexually transmitted disease knowledge, diagnosis, and treatment. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2021, 48, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, D.C.; Hariri, S.; Kamb, M.; Mark, J.; Ilunga, R.; Forhan, S.; Likibi, M.; Lewis, D.A. Quality of sexually transmitted infection case management services in Gauteng Province, South Africa: An evaluation of health providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2016, 43, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Education and Training: Technical Series on Safer Primary Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/252271/9789241511605-eng.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Oyebola, O.G.; Debra, J.; Thubelihle, M. PMTCT Data Management and Reporting during the Transition Phase of Implementing the Rationalised Registers in Amathole District, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritshidze Survey. Community-Led Clinic Monitoring in South Africa. 2024. Available online: https://ritshidze.org.za/it-is-an-inconvenience-to-waste-another-day-waiting-in-the-queues-i-worried-if-it-was-really-my-medicine/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Ritshidze Survey. Community-Led Clinic Monitoring in South Africa. 2023. Available online: https://ritshidze.org.za/ritshidze-survey-of-over-22000-patients-in-over-400-clinics-across-south-africa-reveals-progress-and-persistent-challenges-for-public-health-users/#:~:text=Most%20of%20the%20challenges%20with,cause%20of%20long%20waiting%20times (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Tisler-Sala, A.; Ojavee, S.E.; Uusküla, A. Treatment of chlamydia and gonorrhoea, compliance with treatment guidelines and factors associatedwith non-compliant prescribing: Findings form a cross-sectional study. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2018, 94, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakoli, F.; Dehghan, M.; Haghdoost, A.A.; Mirzazadeh, A.; Gouya, M.M.; Sharifi, H. A qualitative study exploring approaches, barriers, and facilitators of the HIV partner notification programme in Kerman, Iran. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etoori, D.; Wringe, A.; Renju, J.; Kabudula, C.W.; Gomez-Olive, F.X.; Reniers, G. Challenges with tracing patients on antiretroviral therapy who are late for clinic appointments in rural South Africa and recommendations for future practice. Glob. Health Action 2020, 13, 1755115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| STI Stakeholders | Age, (Years) | Gender | Qualifications | Job Title | Years of Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | Female | Diploma | Professional nurse | 24 |

| 2 | 35 | Female | Hons degree | Facility manager | 10 |

| 3 | 58 | Male | Degree | Facility manager | 26 |

| 4 | 39 | Female | Diploma | Professional nurse | 18 |

| 5 | 51 | Female | Degree | Facility manager | 26 |

| 6 | 46 | Female | Gr 12 | Professional nurse | 22 |

| 7 | 34 | Female | Diploma | Professional nurse | 7 |

| 8 | 48 | Female | Diploma | Professional nurse | 31 |

| 9 | 50 | Female | Degree | Facility manager | 21 |

| 10 | 33 | Female | Degree | Professional nurse | 7 |

| 11 | 50 | Female | Diploma | Professional nurse | 25 |

| 12 | 53 | Female | Degree | Facility manager | 26 |

| 13 | 64 | Female | Diploma | Professional nurse | 13 |

| 14 | 30 | Female | Diploma | Professional nurse | 7 |

| 15 | 31 | Female | Degree | Facility manager | 6 |

| 16 | 47 | Female | PhD | Epidemiologist | 9 |

| 17 | 51 | Female | Diploma | Lab manager | 10 |

| 18 | 55 | Female | MPH. Degree | Dep director | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seloka, M.A.; Phalane, E.; Phaswana-Mafuya, R.N. Stakeholders’ Roles and Views in the Provision of Sexually Transmitted Infection Services Among Key and Priority Populations in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2262. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182262

Seloka MA, Phalane E, Phaswana-Mafuya RN. Stakeholders’ Roles and Views in the Provision of Sexually Transmitted Infection Services Among Key and Priority Populations in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2262. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182262

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeloka, Mohlago Ablonia, Edith Phalane, and Refilwe Nancy Phaswana-Mafuya. 2025. "Stakeholders’ Roles and Views in the Provision of Sexually Transmitted Infection Services Among Key and Priority Populations in Limpopo Province, South Africa" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2262. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182262

APA StyleSeloka, M. A., Phalane, E., & Phaswana-Mafuya, R. N. (2025). Stakeholders’ Roles and Views in the Provision of Sexually Transmitted Infection Services Among Key and Priority Populations in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Healthcare, 13(18), 2262. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182262