The Impact of Nutritional Knowledge of Mothers on Their Children’s Nutritional Knowledge and Weight Status †

Abstract

1. Significance

2. Introduction

3. Research Questions

4. Methods

4.1. Study Design and Participants

4.2. Data Collection

4.2.1. Mothers Questionnaire

4.2.2. Children’s Knowledge and Practices

4.2.3. Anthropometric Measurements

- Obesity: BMI-for-age z-score > +2 SD, equivalent to a BMI of 30 kg/m2 at 19 years of age;

- Overweight: BMI-for-age z-score > +1 standard deviation (SD), equivalent to a BMI of 25 kg/m2 at 19 years of age;

- Thinness: BMI-for-age z-score < −2 SD;

- Severe thinness: BMI-for-age z-score < −3 SD.

4.2.4. Sample Size

4.2.5. Statistical Analyses

5. Results

5.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Mothers and Children

5.2. Mothers’ General Nutritional Knowledge Questionnaire (GNKQ)

5.3. Children’s Nutritional Knowledge Classifications and Eating Habits

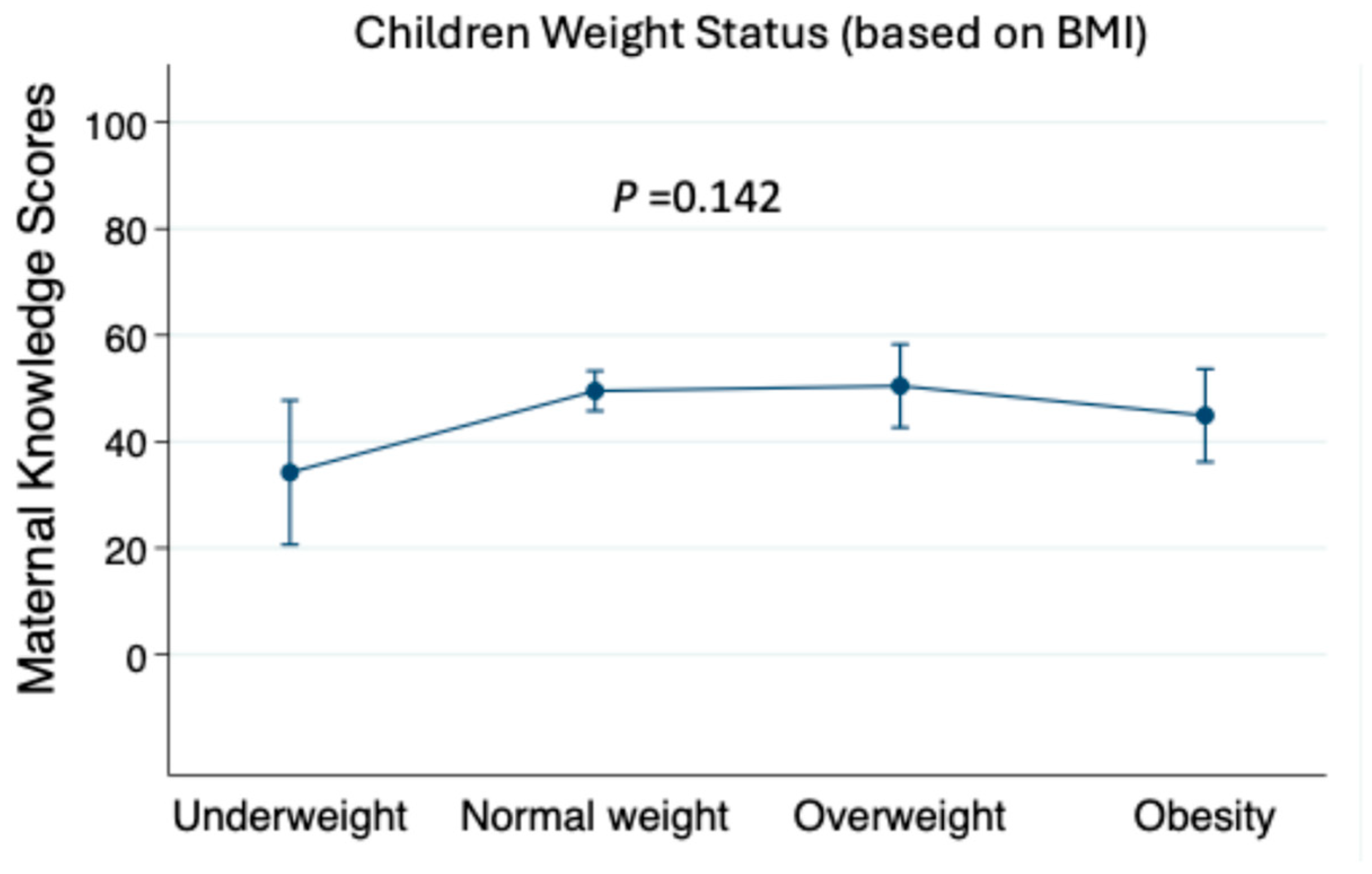

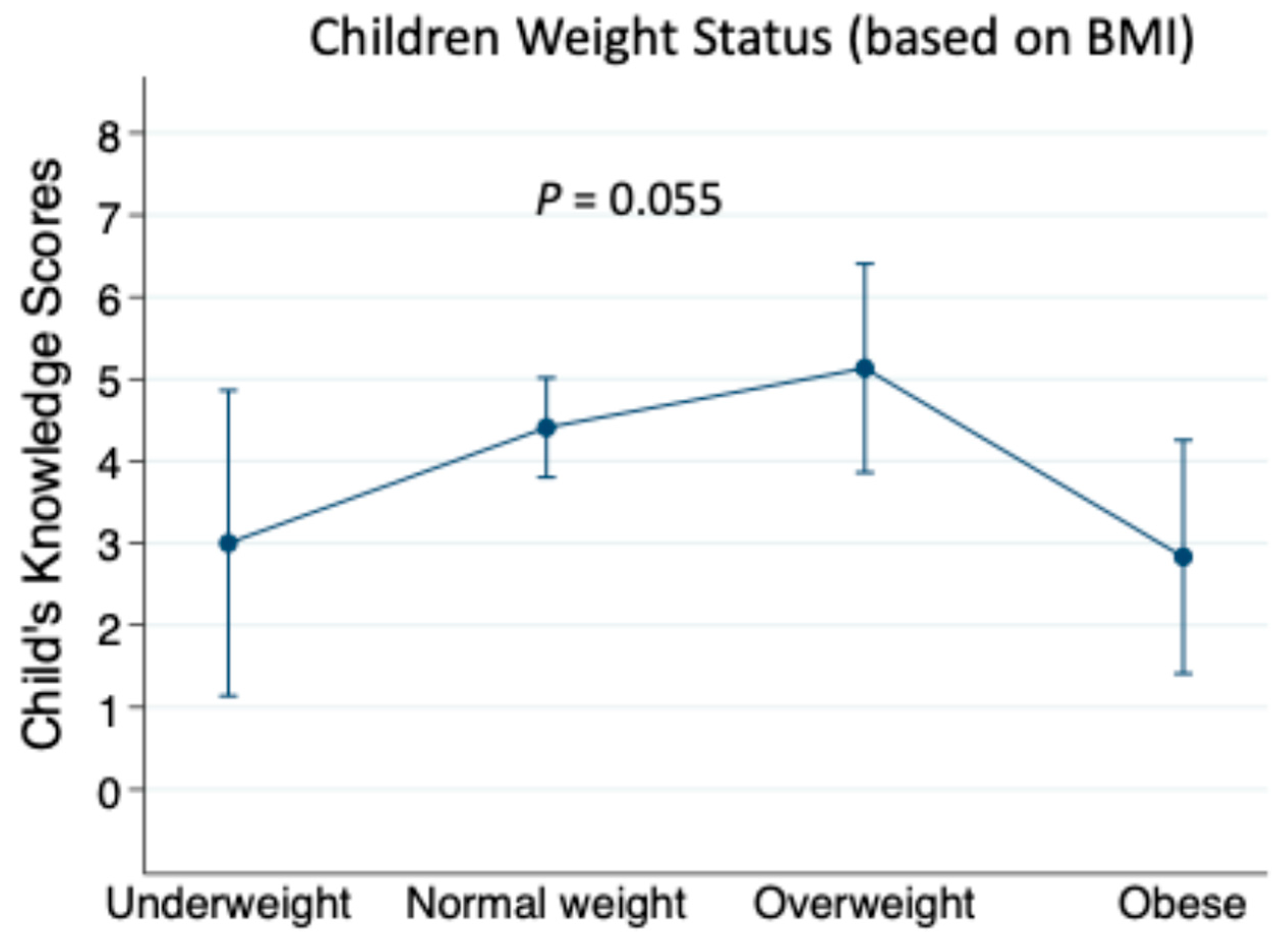

5.4. Relationship Between Maternal Nutritional Knowledge and Children’s Nutritional Knowledge and Weight Status

6. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations and Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ben-Arieh, A.; Casas, F.; Frønes, I.; Korbin, J.E. Multifaceted concept of child well-being. In Handbook of Child Well-Being: Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarino, G.; Corsello, A.; Corsello, G. Macronutrient balance and micronutrient amounts through growth and development. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundborg, P.; Rooth, D.O.; Alex-Petersen, J. Long-term effects of childhood nutrition: Evidence from a school lunch reform. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2022, 89, 876–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, F.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S.; Leon, M.J.; Rivero-Pino, F. Effects of malnutrition on the immune system and infection and the role of nutritional strategies regarding improvements in children’s health status: A literature review. Nutrients 2023, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.; Ag Daud, D.M.; Ligadu, C.P. Overweight and obese children’s psychosocial effects: A review of the literature. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hazzaa, H.M.; Alrasheedi, A.A.; Alsulaimani, R.A.; Jabri, L.; Alhowikan, A.M.; Alhussain, M.H.; Bawaked, R.A.; Alqahtani, S.A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among saudi children: A comparison of two widely used international standards and the national growth references. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 954755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzioumis, E.A.L.S. Childhood dual burden of under- and overnutrition in low- and middle-income countries: A critical review. Food Nutr. Bull. 2014, 35, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Precious, F.K.; Owhor, G.A.; Opeyemi, M.O.A.; Igwe, S.C.; Beauty, O.C.; Sy, F.A.R.; Yepes, P.I.G.; Ayuba, D.; Ogaya, J.B.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E. Why nutrition programs for children remain important. Adv. Food Secur. Sustain. 2023, 8, 187–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Parmenter, K.; Waller, J. Nutrition knowledge and food intake. Appetite 2000, 34, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epuru, S.; Usweed Humaid Al Shammary, M. Nutrition knowledge and its impact on food choices among the students of Saudi Arabia. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2014, 13, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, K.M.; Barnes, C.; Yoong, S.; Campbell, E.; Wyse, R.; Delaney, T.; Brown, A.; Stacey, F.; Davies, L.; Lorien, S.; et al. School-based nutrition interventions in children aged 6 to 18 years: An umbrella review of systematic reviews. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Huang, J.; Eagan, L.; Oldenburg, D. Influence of school-based nutrition education program on healthy eating literacy and healthy food choice among primary school children. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2019, 57, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, C.; Maes, L. Young children’s dietary habits and associations with the mothers’ nutritional knowledge and attitudes. Appetite 2010, 54, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos-Nanclares, A.; Zazpe, I.; Santiago, S.; Marín, L.; Rico-Campà, A.; Martín-Calvo, N. Influence of parental healthy-eating attitudes and nutritional knowledge on nutritional adequacy and diet quality among preschoolers: The SENDO Project. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoabadi, R.H.; Hanbazaza, M.A. Knowledge, Attitude and purchasing behavior of saudi mothers towards food additives and dietary pattern of preschool children. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookari, K. A Cross-sectional exploratory study of food literacy among saudi parents of adolescent children aged 10 to 19 years. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1083118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bataineh, M.F.; Attlee, A. Reliability and validity of arabic version of revised general nutrition knowledge questionnaire on university students. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.B.; Piccoli, Â.B.; Pellanda, L.C. Knowledge and food practices questionnaire: Construction and validation. J. Pediatr. 2021, 97, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kigaru, D.M.D.; Loechl, C.; Moleah, T.; Macharia-Mutie, C.W.; Ndungu, Z.W. Nutrition knowledge, attitude and practices among urban primary school children in Nairobi City, Kenya: A KAP study. BMC Nutr. 2015, 1, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Standards for Improving the Quality of Care for Children and Young Adolescents in Health Facilities. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565554 (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. Growth Reference Data for 5-19 Years: WHO AnthroPlus Software. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/application-tools (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Iheme, G.; Uzokwe, C.; Ezenwa, H.; Nwamadi, C.; Okonkwo, E.; Matthew, S. Application of WHO 2007 growth reference in assessing the anthropometric status of nigerian adolescents: A systematic review and meta analysis. Hum. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 28, 200144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdfelder, E.; FAul, F.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamed, A.; Al-Zeer, A.; Alsaawi, F.; Alshaikh, A.; Alzaher, A.; Alkattan, A.; Alrasheed, N.; Sagor, K.; Alsalem, E.; Ibrahim, M.; et al. The shifting patterns of childhood obesity: Insights from national school screening data. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazi, S.; Alajlan, R.; Alkhalaf, H.; Abolfotouh, M.; Alharbi, O.; Alfawaz, R.; Aldebasi, B.; Alghnam, S. Prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents in Saudi Arabia: A multicenter population-based study. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, J.A.; Patton, G.C.; Cini, K.I.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbas, N.; Abd Al Magied, A.H.A.; Abd ElHafeez, S.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; Abdollahi, A.; Abdoun, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of child and adolescent overweight and obesity, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: A forecasting study for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 785–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Yateem, N.; Rossiter, R. Nutritional knowledge and habits of adolescents aged 9 to 13 years in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: A crosssectional study. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2017, 23, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoteit, M.; Chamas, Z.; Assaf, S.; Bouhairie, M.M.; Bahr, A.; Daccache, R.; Matar, R.; Hallal, M.; Maitar, M.; Hallal, M.; et al. Nutritional status, nutrient imbalances, food-related behaviors and dietary supplements use among patients with celiac disease in lebanon: A national cross-sectional study. F1000Research 2022, 11, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Education. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/ministry/mediacenter/news/pages/news-2025-04-29-001.aspx (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Prasetyo, Y.B.; Permatasari, P.; Susanti, H.D. The effect of mothers’ nutritional education and knowledge on children’s nutritional status: A systematic review. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 2023, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Zainuddin, L.R.; Mohd Amil, I.I.; Hussin, N. Association between sociodemographic factors and nutritional knowledge among working mothers in Terengganu. Asian J. Med. Biomed. 2023, 1, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costarelli, V.; Michou, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Lionis, C. Parental health literacy & nutrition literacy affect child feeding practices: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. Health 2021, 28, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Akpene Amenya, P.C.; Annan, R.A.; Apprey, C.; Agbley, E.N. The relationship between nutrition and physical activity knowledge and body mass index-for-age of school-aged children in selected schools in Ghana. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imad, N.; Turon, H.; Grady, A.; Keenan, S.; Wyse, R.; Wolfenden, L.; Almond, H.; Belski, R.; Leonard, A.; Peeters, A.; et al. Identifying effective obesity prevention intervention components: An umbrella review mapping systematic review evidence. Obes. Rev. 2024, 26, e13878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogna, T.; Serane, V.K.; Chandramohan, A.; Bhavanani, A.B.; Palanisamy, S. Effects of a school-based multicomponent intervention on the behavior and anthropometry of overweight and obese children aged 10-13 years—A randomized control trial. J. Pediatr. Acad. 2025, 6, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Hassan, M.A.; Kim, H.J.; Gao, Z. Comparative effectiveness of lifestyle interventions on children’s body composition management: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Sport Health Sci. 2025, 14, 101008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Arabia Social Media Statistics 2024. Available online: https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/saudi-arabia-social-media-statistics/ (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Hemdi, A.D.D. The effectiveness of a psychoeducation intervention delivered via WhatsApp for mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A randomized controlled trial. Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 43, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinehr, T.; Kersting, M.; Chahda, C.; Andler, W. Nutritional knowledge of obese compared to non-obese children. Nutr. Res. 2003, 23, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Mothers (n = 60) |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| 21–30 years old | 10 (16.67%) |

| 31–40 years old | 31 (51.67%) |

| 41–50 years old | 17 (28.33%) |

| >50 years old | 2 (3.33%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 57 (95%) |

| Separated/divorced | 3 (5%) |

| Education | |

| <Bachelor’s degree | 18 (30%) |

| ≥Bachelor’s degree | 42 (70%) |

| Nutritional knowledge qualifications | |

| Yes | 6 (10%) |

| No | 54 (90%) |

| Perceived health status | |

| Excellent | 14 (23.33%) |

| Very good | 13 (21.67%) |

| Good | 21 (35%) |

| Moderate | 8 (13.33%) |

| Weak | 4 (6.67%) |

| BMI classification 1 | |

| Underweight | 0 |

| Normal weight | 24 (40%) |

| Overweight | 18 (30%) |

| Obesity | 18 (30%) |

| Parameter | Children (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 51 (51%) |

| Male | 49 (49%) |

| Age group | |

| 5–6 years old | 21 (21%) |

| 7–9 years old | 39 (39%) |

| 10–12 years old | 40 (40%) |

| BMI classification 1 | |

| Underweight | 7 (7%) |

| Normal weight | 66 (66%) |

| Overweight | 15 (15%) |

| Obesity | 12 (12%) |

| Parameter | All (n = 60) | Mean Percent of Correct Answers |

|---|---|---|

| GNKQ score | 48.32 ± 15.09 | 56.18 ± 17.55% |

| Nutritional knowledge categories 1 | ||

| High | 4 (6.67%) | |

| Moderate | 38 (63.33%) | |

| Low | 18 (30.00%) | |

| GNKQ scores by GNKQ section | ||

| Experts advise | 12.32 ± 4.15 | 55.1 ± 19.1% |

| Food groups | 17.55 ± 6.27 | 56.9 ± 20.2% |

| Food choices | 5.32 ± 2.50 | 44.3 ± 20.8% |

| Health problems and weight management | 13.13 ± 4.10 | 62.5 ± 19.5% |

| Parameter | Children (n = 100) |

|---|---|

| Children knowledge score 1 | 4.23 ± 2.54 |

| Low nutritional knowledge | 54 (54%) |

| Moderate nutritional knowledge | 30 (30%) |

| High nutritional knowledge | 16 (16%) |

| Fast food consumption 2 | |

| Never | 3 (3%) |

| Sometimes | 50 (50%) |

| Often | 33 (33%) |

| Daily | 7 (7%) |

| Rarely | 7 (7%) |

| Fruit consumption 2 | |

| Never | 5 (5%) |

| Sometimes | 24 (24%) |

| Often | 46 (46%) |

| Daily | 22 (22%) |

| Rarely | 3 (3%) |

| Vegetable consumption 2 | |

| Never | 14 (14%) |

| Sometime | 37 (37%) |

| Often | 40 (40%) |

| Daily | 6 (6%) |

| Rarely | 3 (3%) |

| Predictors | B (95% CI) | SE | T | Standardized Coefficient β |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children, age, years | 0.61 (0.47, 0.75) *** | 0.07 | 8.70 | 0.55 |

| Children, sex (boys vs. girls) | −0.52 (−1.27, 0.24) | 0.38 | −1.38 | −0.10 |

| Mothers, age. > 30 vs. ≤30 years | 0.51 (−0.54, 1.57) | 0.53 | 0.98 | 0.08 |

| Mothers, marital status (separated vs. married) | 0.41 (−0.73, 1.55) | 0.57 | 0.72 | 0.03 |

| Mothers, education (≥Bachelor’s degree vs. <Bachelor’s degree) | 0.01 (−1.02, 1.04) | 0.51 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Mothers, nutritional qualification (yes vs. no) | 1.23 (−0.44, 2.91) | 0.84 | 1.47 | 0.15 |

| Mothers. BMI, kg/m2 | −0.01 (−0.07, 0.04) | 0.03 | −0.42 | −0.03 |

| Mothers’ nutritional knowledge scores | 0.06 (0.02, 0.09) *** | 0.02 | 2.80 | 0.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghabashi, M.A.; Babateen, A.M.; Zagzoog, A.M.; Aljaadi, A.M. The Impact of Nutritional Knowledge of Mothers on Their Children’s Nutritional Knowledge and Weight Status. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2226. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172226

Ghabashi MA, Babateen AM, Zagzoog AM, Aljaadi AM. The Impact of Nutritional Knowledge of Mothers on Their Children’s Nutritional Knowledge and Weight Status. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2226. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172226

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhabashi, Mai Adil, Abrar M. Babateen, Alyaa M. Zagzoog, and Abeer M. Aljaadi. 2025. "The Impact of Nutritional Knowledge of Mothers on Their Children’s Nutritional Knowledge and Weight Status" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2226. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172226

APA StyleGhabashi, M. A., Babateen, A. M., Zagzoog, A. M., & Aljaadi, A. M. (2025). The Impact of Nutritional Knowledge of Mothers on Their Children’s Nutritional Knowledge and Weight Status. Healthcare, 13(17), 2226. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172226