COVID-19-Related Effects on the Psychological Well-Being and Resilience of Frontline Expatriate Nurses in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Sample and Sampling Technique

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Collection Process

- (i)

- How do frontline expatriate nurses experience and make sense of the psychological impact of caring for COVID-19 patients in the KSA?

- -

- Could you share your experiences related to working on the frontline and delivering care to patients suspected or confirmed to have contracted the coronavirus during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- -

- How do you describe your nursing care of patients suspected of or diagnosed with COVID-19 infection?

- -

- What are your feelings when providing care for a patient suspected of or diagnosed with COVID-19?

- -

- What are your concerns, fears, and anxieties related to caring for or being exposed to COVID-19 patients?

- -

- How did the COVID-19 pandemic cause stress in your life and did it also dramatically affect you and your family abroad in your home country?

- -

- What are the issues and challenges you encountered in caring for patients suspected of or diagnosed with COVID-19 infection?

- (ii)

- How do frontline expatriate nurses navigate psychological challenges and foster resilience while caring for COVID-19 patients?

- -

- How has the COVID-19 pandemic influenced your temperament, emotions, and feelings regarding the management of your psychological challenges?

- -

- What actions did your hospital undertake to assess, identify, or address the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on your psychological well-being?

- -

- What should healthcare workers or administrators do for the psychological well-being challenges experienced related to COVID-19?

- -

- How did your hospital organization consider the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health, well-being, and quality of life of expatriate nurses?

- (iii)

- How does the expatriate status of frontline expatriate nurses shape their psychological experiences and access to resilience-building resources during the COVID-19 pandemic in the KSA?

- -

- How do you cope with your psychological well-being issues while caring or being exposed to COVID-19-infected patients?

- -

- What mental health services, resources, and support did you have throughout the COVID-19 pandemic?

- -

- What ways or strategies did you undertake to maintain your own protection against COVID-19 and to maintain your resilience and psychological well-being?

- -

- What are your thoughts on the methods to be employed by hospital organizations to support and protect the psychological well-being of expatriate nurses in preparation for future pandemics?

2.5. Rigor

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

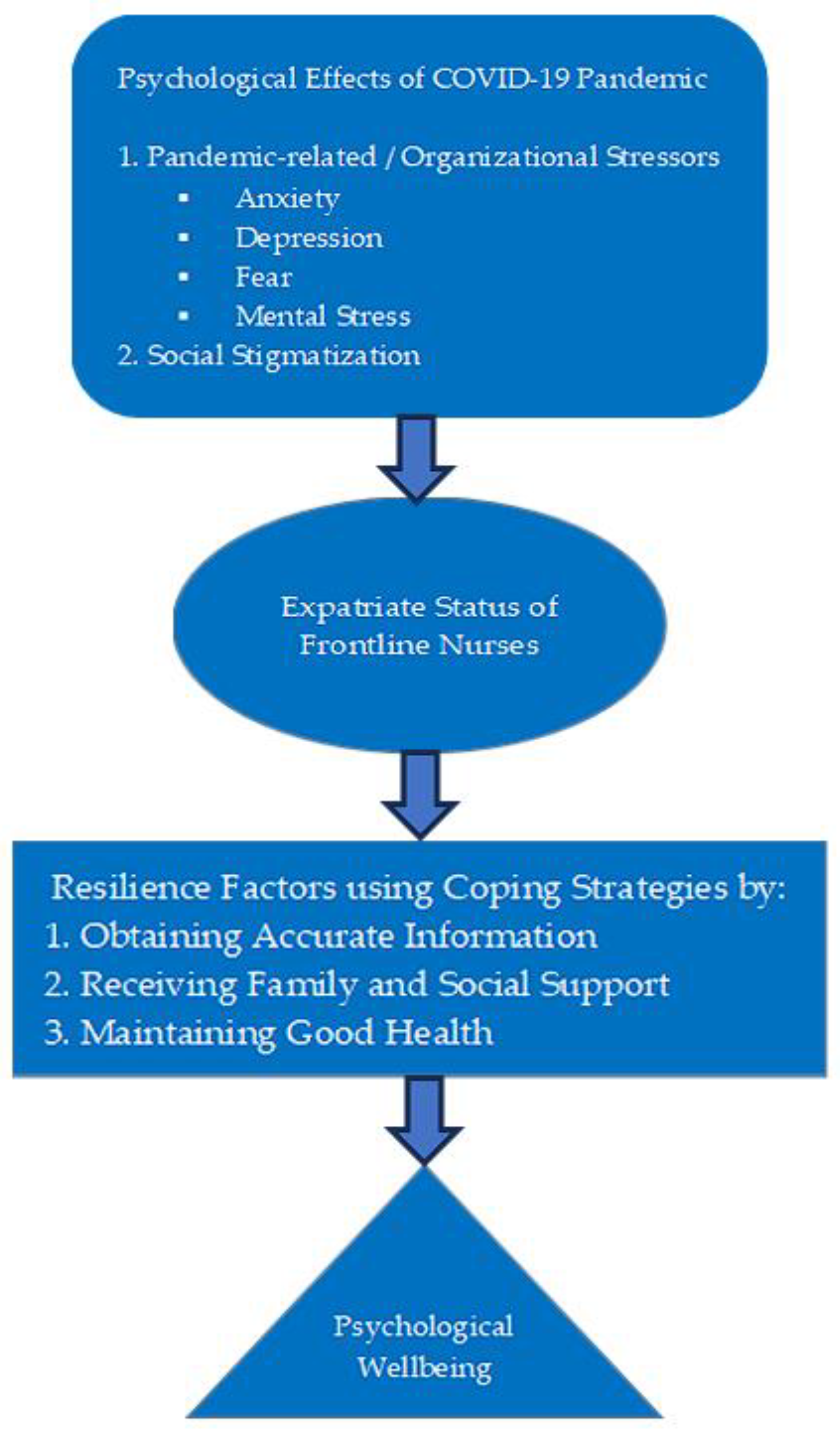

3.1. Major Theme 1—Psychological Effects Due to Fear of Contracting the Corona Virus

3.2. Major Theme 2—Resilience to Cope with the Challenges Associated with the Pandemic

4. Discussion

5. Implications and Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Word Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/emergencies/covid-19 (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Word Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 Epidemiological Update—15 July 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update-edition-169 (accessed on 24 December 2024).

- Koh, D. Occupational risks for COVID-19 infection. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, M.; Liu, F. Reasons for healthcare workers becoming infected with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, H.; Lucey, D.R. Healthcare worker infections and deaths due to COVID-19: A survey from 37 nations and a call for WHO to post national data on their website. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 102, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations During the COVID-19 Outbreak; World Health Organization Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Maintaining Essential Health Services During the COVID-19 Outbreak. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/related-health-issues (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Baticulon, R.E.; Kadhum, M.; Alser, M.; Ojuka, D.K.; Badereddin, Y.; Kamath, A.; Parepalli, S.A.; Brown, G.; Iharchane, S.; et al. Infection and mortality of healthcare workers worldwide from COVID-19: A systematic review. BMJ Global Health 2020, 5, e003097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, J.J.; Donoho, D.A.; Forman, H.P. Hospital capacity and operations in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic—Planning for the nth patient. JAMA Health Forum 2020, 1, e200345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liang, M.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Fei, D.; Wang, L.; He, L.; Sheng, C.; Cai, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e15–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legido-Quigley, H.; Mateos-García, J.T.; Campos, V.R.; Gea-Sánchez, M.; Muntaner, C.; McKee, M. The resilience of the Spanish health system against the COVID19 pandemic. Lancet Public Health 2020, 2667, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Report of the policy dialogue meeting on the nursing workforce. In Dialogue Meeting; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Al Muharraq, E.H. The Psychological Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 on Nurses in Saudi Arabia and Their Coping Strategies. SAGE Open Nurs. 2021, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Omari, O.; Al Sabei, S.; Al Rawajfah, O.; Abu Sharour, L.; Aljohani, K.; Alomari, K.; Shkman, L.; Al Dameery, K.; Saifan, A.; Al Zubidi, B.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of depression, anxiety, and stress among youth at the time of COVID-19: An online cross-sectional multicountry study. Depress. Res. Treat. 2020, 2020, 8887727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, L.; Li, H.; Pan, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Wu, Q.; Wei, H. The Psychological Change Process of Frontline Nurses Caring for Patients with COVID-19 during Its Outbreak. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 41, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, J.; Qu, D.; Li, W.; Zhu, Y. Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Emergency Dental Care Providers on the Frontlines in China. Int. Dent. J. 2020, 71, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, D.Y.; Bai, J.; Fu, J.-C.; Jiang, F.; Nehl, E.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Tang, Y.-L.; et al. Psychological effects of trauma, negative and positive coping, resilience, and psychological distress among Chinese healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Mood Anxiety Disord. 2024, 5, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; de Los Santos, J.A.A. Fear of COVID-19, psychological distress, work satisfaction and turnover intention among frontline nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, S.M.D.R.; Novais, R.M.F.; Martins, M.F.D.S.V. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on nurses’ psychological well being in an emergency room. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2022, 76 (Suppl. 1), e20220171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloweni, F.; Ayre, T.C.; Teo, I.; Tan, H.K.; Lim, S.H. A year after COVID-19: Its impact on nurses’ psychological well-being. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 2585–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.J.; Jun, J.Y. Mental health and psychological intervention amid COVID-19 outbreak: Perspectives from South Korea. Yonsei Med. J. 2020, 61, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norful, A.A.; Haghighi, F.; Shechter, A. Assessing sleep health dimensions in frontline registered nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for psychological health and wellbeing. Sleep Adv. 2022, 4, zpac046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balay-odao, E.M.; Alquwez, N.; Inocian, E.P.; Alotaibi, R.S. Hospital Preparedness, Resilience, and Psychological Burden Among Clinical Nurses in Addressing the COVID-19 Crisis in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 573932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Wahed, W.Y.; Hefzy, E.M.; Ahmed, M.I.; Hamed, N.S. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perception of Health Care Workers Regarding COVID-19, A Cross-Sectional Study from Egypt. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, R.; Hosseini, S.M.; Momeni, M.; Maghari, A.; Fathi-Ashtiani, A.; Ghadimi, P.; Heiat, M.; Barmayoon, P.; Mohamadianamiri, M.; Bahardoust, M.; et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infection-Related Stigma, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Iranian Healthcare Workers. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaci, T.; Barattucci, M.; Ledda, C.; Rapisarda, V. Social Stigma during COVID-19 and its Impact on HCWs Outcomes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhammad, S.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Al-Azzam, S.; Alshogran, O.Y.; Ikhrewish, R.E.; Amer, Z.W.B.; Suliman, M.M. Stigma toward healthcare providers from patients during COVID-19 era in Jordan. Public Health Nurs. 2022, 39, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Choi, S.; Cho, S.H.; Lee, J.; Yun, J.Y. Associations between the working experiences at frontline of COVID-19 pandemic and mental health of Korean public health doctors. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, G.K.; Strong, C.; Chan, Y.H.; Chung, R.Y.; Chen, J.S.; Lin, Y.H.; Huang, R.Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Ko, N.Y. Psychological Distress and Protective Behaviors During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Different Populations: Hong Kong General Population, Taiwan Healthcare Workers, and Taiwan Outpatients. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 800962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wert, M.J.; Gandhi, S.; Gupta, I.; Singh, A.; Eid, S.M.; Haroon Burhanullah, M.; Michtalik, H.; Malik, M. Healthcare Worker Mental Health After the Initial Peak of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A US Medical Center Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusty, W.T.; Swift, J.K.; Higgins, H.J. Stigma and Intentions to Seek Psychotherapy Among Primary Care Providers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mediational Analysis. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2023, 30, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althumiri, N.A.; Basyouni, M.H.; BinDhim, N.F. Consistency and sensitivity evaluation of the Saudi Arabia Mental Health Surveillance System (MHSS): Hypothesis generation and testing. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e23965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BinDhim, N.F.; Althumiri, N.A.; Basyouni, M.H.; Alageel, A.A.; Alghnam, S.; Al-Qunaibet, A.M.; Almubarak, R.A.; Aldhukair, S.; Ad-Dab’bagh, Y. Saudi Arabia Mental Health Surveillance System (MHSS): Mental health trends amid COVID-19 and comparison with pre-COVID-19 trends. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2021, 12, 1875642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BinDhim, N.F.; Althumiri, N.A.; Basyouni, M.H.; Alageel, A.A.; Alghnam, S.; Al-Qunaibet, A.M.; Almubark, R.A.; Aldhukair, S.; Ad-Dab’bagh, Y. A mental health surveillance system for the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: Protocol for a multiwave cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e23748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabeeb, A.A.; Al-Duraihem, R.A.; Alasmary, S.; Alkhamaali, Z.; Althumiri, N.A.; BinDhim, N.F. National screening for anxiety and depression in Saudi Arabia 2022. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1213851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D. Examining characteristics of descriptive phenomenological nursing studies: A scoping review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1968–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, K.A.; Willis, D.G. Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, I.; Galvin, K. Qualitative Research in Nursing and Healthcare, 4th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch, P.I.; Ness, L.R. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrish, K.; Lacey, A. The Research Process in Nursing, 6th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, C.; Hadfield, M.; Hutchings, M.; de Eyto, A. Ensuring Rigor in Qualitative Data Analysis: A Design Research Approach to Coding Combining NVivo with Traditional Material Methods. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2018, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y. Fourth Generation Evaluation; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.; Rasulova, S. Qualitative research and the evaluation of development impact: Incorporating authenticity into the assessment of rigour. J. Dev. Eff. 2017, 9, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamawe, F.C. The Implication of Using NVivo Software in Qualitative Data Analysis: Evidence-Based Reflections. Malawi Med. J. 2015, 27, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, T.; McKenna, L.; Buck, M.; Alharbi, R.J. Reported effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological status of emergency healthcare workers: A scoping review. Australas. Emerg. Care 2021, 25, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, A.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Cheung, T.; Ungvari, G.S.; Qin, M.Z.; An, F.R.; Xiang, Y.T. Prevalence of depression and its impact on quality of life among frontline nurses in emergency departments during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Fu, W.; Liu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, R.; Zhou, N.; Yan, S.; Lv, C. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the Coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-González, S.; Selva-Medrano, D.; López-Espuela, F.; Caro-Alonso, P.Á.; Novo, A.; Rodríguez-Martín, B. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Front Line Nurses: A Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinbilek, E.; Ozturk, D.; Erdem, S.C. COVID-19 adversely affects the psychological status of healthcare workers in the emergency room. Ann. Clin. Anal. Med. 2021, 12, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araç, S.; Dönmezdil, S. Investigation of mental health among hospital workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2020, 138, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadi, M.; Msherghi, A.; Elgzairi, M.; Alhashimi, A.; Bouhuwaish, A.; Biala, M.; Abuelmeda, S.; Khel, S.; Khaled, A.; Alsoufi, A.; et al. The Mental Well-Being of Frontline Physicians Working in Civil Wars Under Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic Conditions. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 598720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, S.; Zhang, L.; Yan, H.; Shi, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chu, J. Experiences and Psychological Adjustments of Nurses Who Voluntarily Supported COVID-19 Patients in Hubei Province, China. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odikpo, L.C.; Abazie, H.O.; Emon, D.; Mobolaji-Olajide, M.O.; Gbahabo, D.D.; Musa-Malikki, A. Knowledge and reasons for anxiety among nurses towards COVID-19 in Nigeria. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 15, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, R.; Lord, H.; Moxham, L.; Middleton, R.; Halcomb, E. Anxiety among Australian nurses during COVID-19. Collegian 2021, 28, 357–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galehdar, N.; Toulabi, T.; Kamran, A.; Heydari, H. Exploring nurses’ perception of taking care of patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A qualitative study. Nurs. Open 2020, 8, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, Z.; Fereidouni, Z.; Behnammoghadam, M.; Alimohammadi, N.; Mousavizadeh, A.; Salehi, T.; Mirzaee, M.S.; Mirzaee, S. The Lived Experience of Nurses Caring for Patients with COVID-19 in Iran: A Phenomenological Study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, F.; Sequeira, C.; Teixeira, L. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on nurses’ mental health: A prospective cohort study. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazi, T.H.; BinDhim, N.F.; Alenazi, M.H.; Tamim, H.; Almagrabi, R.S.; Aljohani, S.M.; H Basyouni, M.; Almubark, R.A.; Althumiri, N.A.; Alqahtani, S.A. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsharif, F. Nurses’ Knowledge and Anxiety Levels toward COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Castillo, R.J.; González-Caro, M.D.; Fernández-García, E.; Porcel-Gálvez, A.M.; Garnacho-Montero, J. Intensive care nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2021, 26, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mutair, A.; Al Mutairi, A.; Ambani, Z.; Shamsan, A.; AlMahmoud, S.; Alhumaid, S. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the level of depression among health care workers: Cross-sectional study. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.E.; Zhai, Z.C.; Han, Y.H.; Liu, Y.L.; Liu, F.P.; Hu, D.Y. Experiences of front-line nurses combating coronavirus disease-2019 in China: A qualitative analysis. Public Health Nurs. 2020, 37, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, M.L.; Moussa, F.L.; Alharbi, H.A.; Omer, T.; Khallaf, S.A.; Al Harbi, H.S.; Albarqi, A.A. Fear of nurses during COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional assessment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 736103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, S.; Xiang, M.; Fang, Y.; Qian, K.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, B. The prevalence and risk factors of PTSD symptoms among medical assistance workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 139, 110270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, K.; Choudhry, F.R. Exploring stress coping strategies of frontline emergency health workers dealing COVID-19 in Pakistan: A qualitative inquiry. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, 49, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Diab, S.; Elmahallawy, E.K. Exploring the Psychological Stress, Anxiety Factors, and Coping Mechanisms of Critical Care Unit Nurses During the COVID-19 Outbreak in Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 767517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Lee, E.H.; Park, N.R.; Choi, Y.H. Mental Health of Nurses Working at a Government-designated Hospital During a MERS-CoV Outbreak: A Cross-sectional Study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.; Lee, H.J. South Korean Nurses’ Experiences with Patient Care at a COVID-19-Designated Hospital: Growth after the Frontline Battle against an Infectious Disease Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeone, S.; Rea, T.; Guillari, A.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R.; Pucciarelli, G. Nurses and Stigma at the Time of COVID-19: A Phenomenological Study. Healthcare 2021, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanot, D.; Singh, T.; Verma, S.K.; Sharad, S. Stigma and Discrimination During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 577018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasay-An, E.; Alshammari, F.; Mostoles, R.; Gattud, V., Jr.; Cajigal, J.; Buta, J. A qualitative study on nurses’ experiences with social stigma in the context of COVID-19. Enferm. Clin. 2022, 32, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehularo, L.A.; Molato, B.J.; Mokgaola, I.O.; Gause, G. Coping strategies used by nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative literature review. Health SA Gesondheid 2021, 26, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Shali, M.; Matourypour, P.; Salehi Morkani, E.; Salehpoor Emran, M.; Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A. Explaining nurses’ experience of stresses and coping mechanisms in coronavirus pandemic. Nurs. Forum 2022, 57, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maideen, A.A.; Idris, D.R.; Lupat, A.; Chung, Y.F.; Haji-Badarudin, H.; Suhai, H.; Abdullah, H.N.; Omar, H.; Kisut, R.; Rahman, H.A.; et al. Nurses’ mental health and coping strategies throughout COVID-19 outbreak: A nationwide qualitative study. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Nurs. 2022, 31, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinuraya, R.K.; Suwantika, A.A.; Postma, M.J. Controlling the COVID-19 pandemic through vaccination: A perspective from Indonesia. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2025, 24, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, V.M.; Patalay, P.; Coronado, J.I.C.; Denholm, R.; Forbes, H.; Stafford, J.; Moltrecht, B.; Palmer, T.; Walker, A.; Thompson, E.J.; et al. COVID-19 and Mental Illnesses in Vaccinated and Unvaccinated People. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.; Thurman, M.; Johnson, S.D.; Acharya, A.; Johnston, M.; Klug, E.A.; Olwenyi, O.A.; Rajaiah, R.; Byrareddy, S.N. Mental Health Issues During and After COVID-19 Vaccine Era. Brain Res. Bull. 2021, 176, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Code | Age (In Years) | Gender | Civil Status | Nationality | Assigned Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse Expat 1 | 33 | Male | Single | Filipino | COVID ward |

| Nurse Expat 2 | 41 | Female | Married | Jordanian | Intensive care unit |

| Nurse Expat 3 | 28 | Male | Single | Filipino | Flu clinic |

| Nurse Expat 4 | 35 | Female | Married | Filipino | Emergency department |

| Nurse Expat 5 | 33 | Female | Married | Indian | Flu clinic |

| Nurse Expat 6 | 52 | Female | Married | Indian | Intensive care unit |

| Nurse Expat 7 | 38 | Female | Married | Filipino | Intensive care unit |

| Nurse Expat 8 | 39 | Female | Married | Indian | Emergency department |

| Nurse Expat 9 | 34 | Male | Married | Indian | Intensive care unit |

| Nurse Expat 10 | 38 | Female | Married | Jordanian | COVID ward |

| Nurse Expat 11 | 43 | Female | Married | Indian | COVID ward |

| Nurse Expat 12 | 40 | Male | Single | Indian | Emergency department |

| Nurse Expat 13 | 35 | Female | Married | Filipino | Intensive care unit |

| Nurse Expat 14 | 36 | Male | Married | Indian | Intensive care unit |

| Nurse Expat 15 | 28 | Female | Single | Indian | Emergency department |

| Nurse Expat 16 | 44 | Female | Married | Filipino | Intensive care unit |

| Nurse Expat 17 | 37 | Female | Married | Jordanian | Flu clinic |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alharbi, H.A. COVID-19-Related Effects on the Psychological Well-Being and Resilience of Frontline Expatriate Nurses in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172200

Alharbi HA. COVID-19-Related Effects on the Psychological Well-Being and Resilience of Frontline Expatriate Nurses in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172200

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlharbi, Homood A. 2025. "COVID-19-Related Effects on the Psychological Well-Being and Resilience of Frontline Expatriate Nurses in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172200

APA StyleAlharbi, H. A. (2025). COVID-19-Related Effects on the Psychological Well-Being and Resilience of Frontline Expatriate Nurses in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Analysis. Healthcare, 13(17), 2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172200