Knowledge Gaps Among Brazilian Healthcare Professionals Regarding Oropouche Virus: A National Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

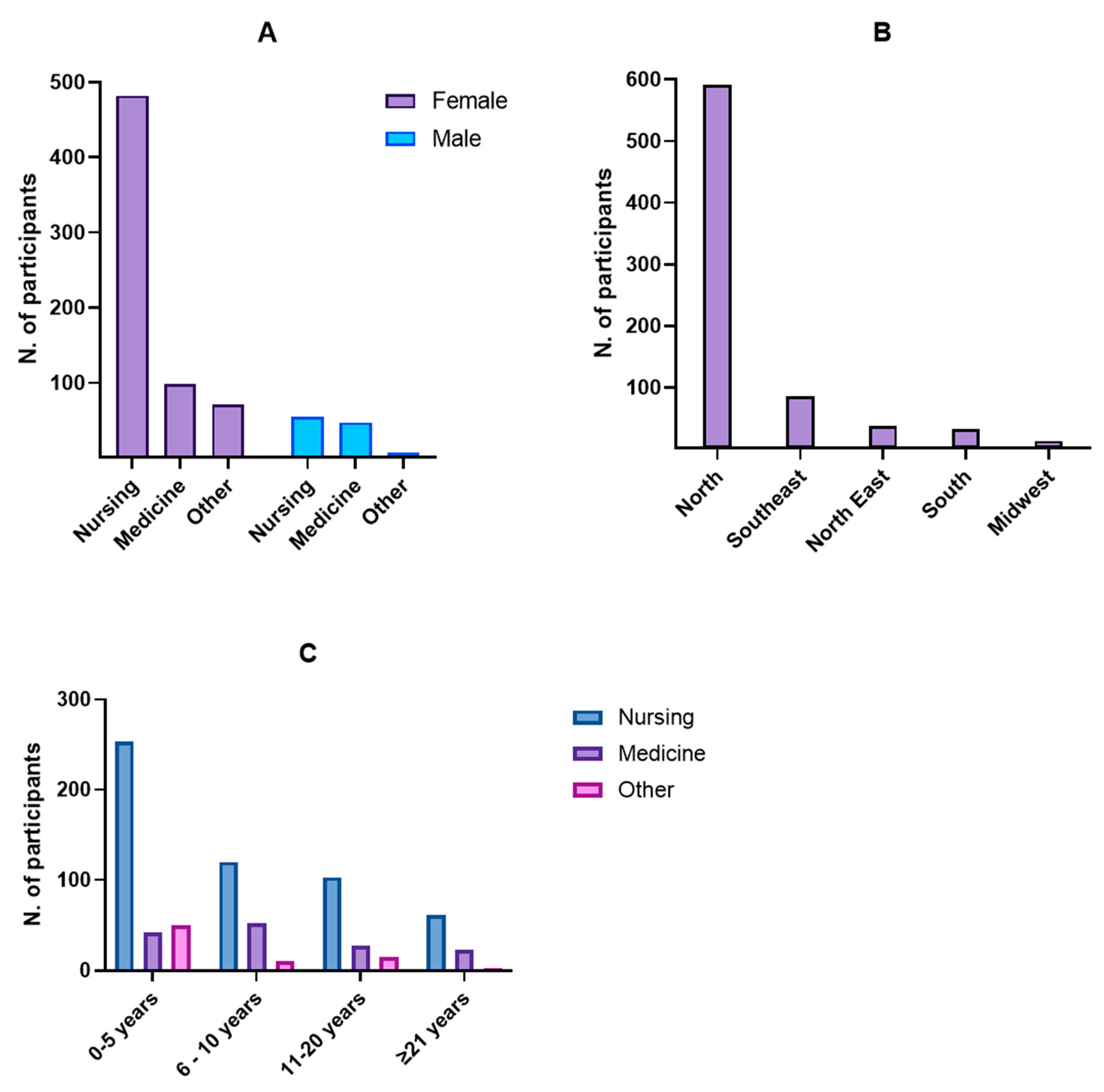

3.1. Participant Characteristics

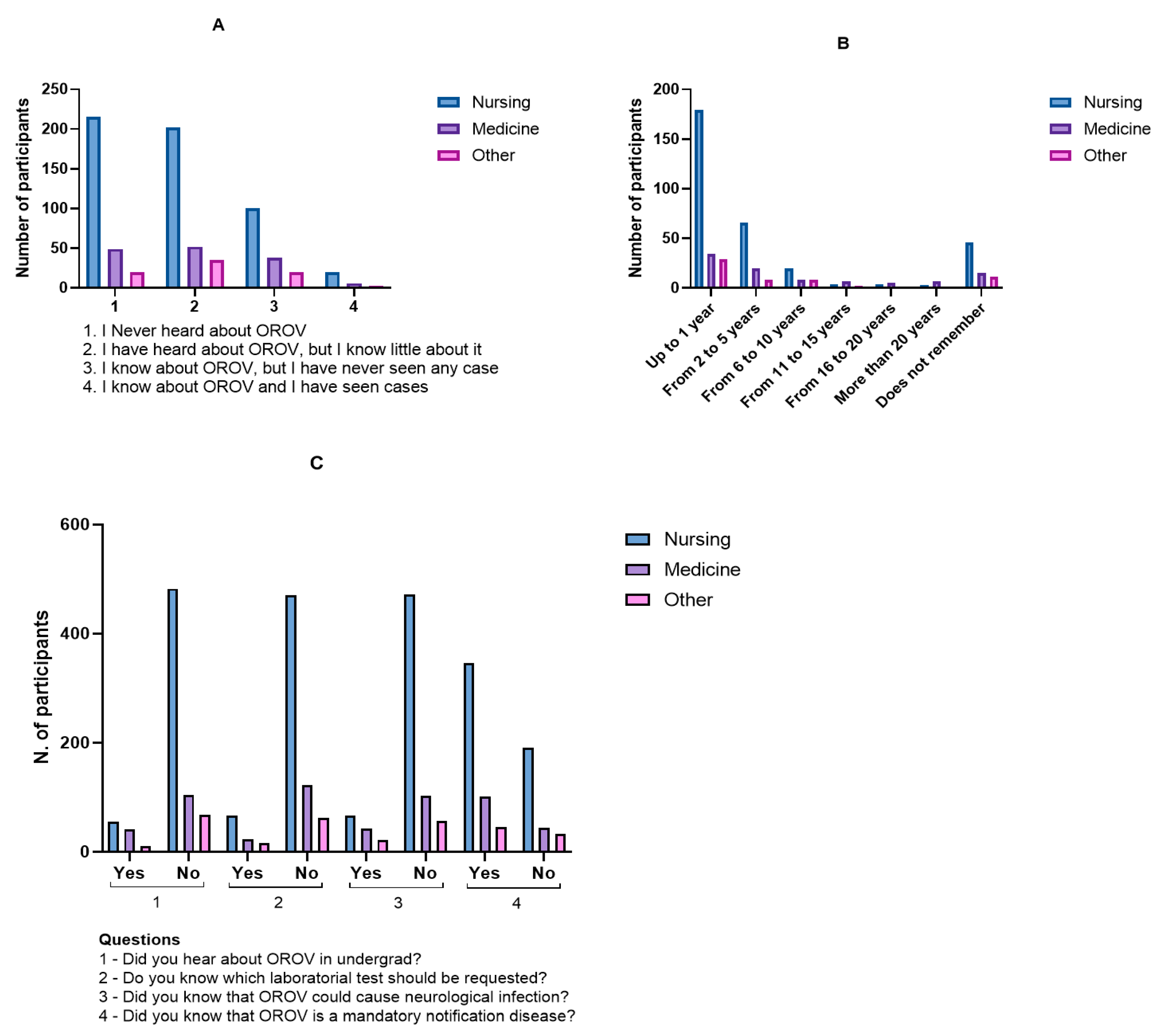

3.2. Knowledge and Awareness of Oropouche Virus

3.3. Educational and Diagnostic Knowledge Gaps

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, C.R.; Spence, L.; Downs, W.G.; Aitken, T.H.G. Oropouche Virus: A New Human Disease Agent from Trinidad, West Indies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1961, 10, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, F.P.; Bensabath, G.; Andrade, A.H.; Lins, Z.C.; Fraiha, H.; Tang, A.T.; Lainson, R.; Shaw, J.J.; Azevedo, M.C. Infectious Diseases along Brazil’s Trans-Amazon Highway: Surveillance and Research. Bull. Pan Am. Health Organ. 1974, 8, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- da Travassos Rosa, J.F.; de Souza, W.M.; de Pinheiro, F.P.; Figueiredo, M.L.; Cardoso, J.F.; Acrani, G.O.; Nunes, M.R.T. Oropouche Virus: Clinical, Epidemiological, and Molecular Aspects of a Neglected Orthobunyavirus. Am. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil Nota Técnica No 6/2024-CGARB/Dedt/SVSA/MS.Orientações Para a Vigilância Da Febre Oropouche. 2024; pp. 1–4. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/notas-tecnicas/2024/nota-tecnica-no-6-2024-cgarb-dedt-svsa-ms/view (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Ayala, M.M.; Díaz, F.; Spinelli, G.R.; Micieli, M.V.; Ronderos, M.M. Redescription of Immature Stages of Culicoides paraensis (Goeldi) (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae), Vector of the Oropouche Virus. Zootaxa 2022, 5205, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feitoza, L.H.M.; de Carvalho, L.P.C.; da Silva, L.R.; Meireles, A.C.A.; Rios, F.G.F.; Silva, G.S.; de Paulo, P.F.M.; Pessoa, F.A.C.; de Medeiros, J.F.; Julião, G.R. Influence of Meteorological and Seasonal Parameters on the Activity of Culicoides paraensis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae), an Annoying Anthropophilic Biting Midge and Putative Vector of Oropouche Virus in Rondônia, Brazilian Amazon. Acta Trop. 2023, 243, 106928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilston-Lunel, N.L. Oropouche Virus: An Emerging Orthobunyavirus. J. Gen. Virol. 2024, 105, 002027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandeira, A.C.; Pereira, F.M.; Leal, A.; Santos, S.P.O.; Barbosa, A.C.; Souza, M.S.P.L.; de Souza, D.R.; Guimaraes, N.; Fonseca, V.; Giovanetti, M.; et al. Fatal Oropouche Virus Infections in Nonendemic Region, Brazil, 2024. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 2370–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, D.A.; Dashraath, P.; Baud, D. Oropouche Virus (OROV) in Pregnancy: An Emerging Cause of Placental and Fetal Infection Associated with Stillbirth and Microcephaly Following Vertical Transmission. Viruses 2024, 16, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organização Pan-Americana de Saúde Avaliação de Risco à Saúde Pública Pelo Vírus Oropouche (OROV) Na Região Das Américas. 2024, pp. 1–10. Available online: https://www.paho.org/pt/documentos/avaliacao-risco-saude-publica-pelo-virus-oropouche-orov-na-regiao-das-americas-9 (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Gutierrez, B.; Wise, E.L.; Pullan, S.T.; Logue, C.H.; Bowden, T.A.; Escalera-Zamudio, M.; Trueba, G.; Nunes, M.R.T.; Faria, N.R.; Pybus, O.G. Evolutionary Dynamics of Oropouche Virus in South America. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01127-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scachetti, G.C.; Forato, J.; Claro, I.M.; Hua, X.; Salgado, B.B.; Vieira, A.; Simeoni, C.L.; Barbosa, A.R.C.; Rosa, I.L.; de Souza, G.F.; et al. Re-Emergence of Oropouche Virus between 2023 and 2024 in Brazil: An Observational Epidemiological Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemida, M.G.; Ba Abduallah, M.M. The SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak from a One Health Perspective. One Health 2020, 10, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.C. Urbanization and Geographic Expansion of Zoonotic Arboviral Diseases: Mechanisms and Potential Strategies for Prevention. Trends Microbiol. 2013, 21, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, L.T.M. Human Urban Arboviruses Can Infect Wild Animals and Jump to Sylvatic Maintenance Cycles in South America. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesselmann, K.M.; Postigo-Hidalgo, I.; Pezzi, L.; de Oliveira-Filho, E.F.; Fischer, C.; de Lamballerie, X.; Drexler, J.F. Emergence of Oropouche Fever in Latin America: A Narrative Review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e439–e452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization. World Health Organization Epidemiological Update: Oropouche in the Region of the Americas, 6 September 2024. Www. Paho.Org. 2024, pp. 1–13. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/epidemiological-update-oropouche-americas-region-6-september-2024 (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Feng, S.; Lu, K.; Zhu, W.; Sun, H.; Niu, G. Oropouche Virus: A Neglected Global Arboviral Threat. Virus Res. 2024, 341, 199318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, R.; Satapathy, P.; Gaidhane, A.M.; Vadia, N.; Menon, S.V.; Chennakesavulu, K.; Panigrahi, R.; Bushi, G.; Singh, M.; Sah, S.; et al. Neurological Manifestations in Oropouche Virus Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2025, 97, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region | Federal State | Profession/Gender | Total | % | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing | Medicine | Other | |||||||||||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | ||||||||||

| N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | ||||

| North | Amapá | 4 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.3 | 8 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.3 | 23 | 3.0 |

| Amazonas | 9 | 1.2 | 4 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 1.7 | |

| Pará | 374 | 49.2 | 42 | 5.5 | 74 | 9.7 | 27 | 3.6 | 33 | 4.3 | 4 | 0.5 | 554 | 72.9 | |

| Rondônia | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | |

| Northeast | Alagoas | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Bahia | 3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.4 | |

| Ceará | 6 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 1.3 | |

| Maranhão | 8 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 1.4 | |

| Paraíba | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.5 | |

| Pernambuco | 3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.8 | |

| Piauí | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | |

| Midwest | Brasília | 3 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 1.3 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | |

| Mato Grosso | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Southeast | Espírito Santo | 3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.4 |

| Minas Gerais | 8 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 2.1 | |

| Rio de Janeiro | 16 | 2.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.3 | 6 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 27 | 3.6 | |

| São Paulo | 20 | 2.6 | 1 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.9 | 7 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 40 | 5.3 | |

| South | Paraná | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.7 |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 10 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 17 | 2.2 | |

| Santa Catarina | 8 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 1.3 | |

| Total | 21 states | 482 | 63.4 | 55 | 7.2 | 98 | 12.9 | 47 | 6.2 | 72 | 9.5 | 6 | 0.8 | 760 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cravo, L.d.C.C.; Azevedo, R.d.S.d.S.; Casseb, L.M.N.; Chiang, J.O. Knowledge Gaps Among Brazilian Healthcare Professionals Regarding Oropouche Virus: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172192

Cravo LdCC, Azevedo RdSdS, Casseb LMN, Chiang JO. Knowledge Gaps Among Brazilian Healthcare Professionals Regarding Oropouche Virus: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172192

Chicago/Turabian StyleCravo, Layna de Cássia Campos, Raimunda do Socorro da Silva Azevedo, Lívia Medeiros Neves Casseb, and Jannifer Oliveira Chiang. 2025. "Knowledge Gaps Among Brazilian Healthcare Professionals Regarding Oropouche Virus: A National Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172192

APA StyleCravo, L. d. C. C., Azevedo, R. d. S. d. S., Casseb, L. M. N., & Chiang, J. O. (2025). Knowledge Gaps Among Brazilian Healthcare Professionals Regarding Oropouche Virus: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(17), 2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172192