Pulmonary Rehabilitation Nursing Interventions Promoting Self-Care in Elderly People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (At Home)

Abstract

1. Introduction

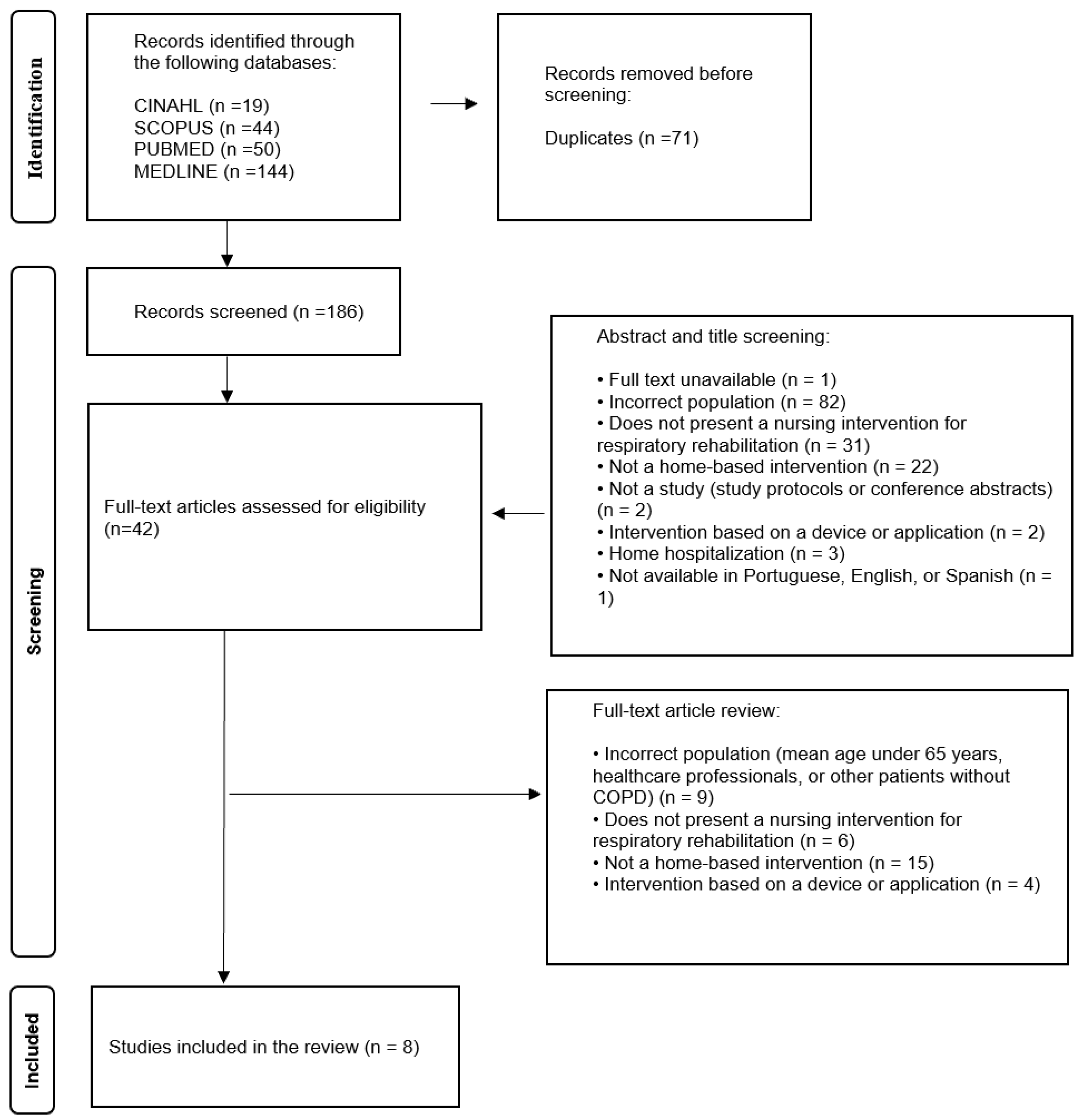

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Research Question and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Research Strategy

2.4. Data Extraction, Quality Appraisal, and Data Synthesis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Eurostat. Demography of Europe—2024 Edition. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/demography-2024#ageing-population (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Eurostat. Population Structure and Ageing. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_structure_and_ageing (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). População Residente Aumenta Mais De 46 Mil Pessoas. 2023. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/ngt_server/attachfileu.jsp?look_parentBoui=616635992&att_display=n&att_download=y (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Wong, A.K.; Bayuo, J.; Wong, F.K.; Yuen, W.S.; Lee, A.Y.; Chang, P.K.; Lai, J.T. Effects of a Nurse-Led Telehealth Self-care Promotion Program on the Quality of Life of Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e31912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollica, M.; Aronne, L.; Paoli, G.; Flora, M.; Mazzeo, G.; Tartaglione, S.; Iadevaia, C. Elderly with COPD: Comoborbitidies and systemic consequences. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 69, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Effects of Continuous Nursing Intervention Combined with Breathing Training Guidance on Improving the Rehabilitation Effect and Self-care Ability of Elderly Patients with COPD. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2024, 30, 242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2024. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Said Sabry, S.; Abdelrazek Mahmoud, A.; Abdallah Abdel-Mordy, M. Effect of Orem’s Self-Care Behavior Model on Quality of Life of Elderly Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Egypt. J. Health Care 2021, 12, 1126–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tan, R.; Long, X.; Tu, H. Applying behavioural change theories to optimize pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e38366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, A.; Canbolat, Ö. Nursing Care of The Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patient According to Orem’s Theory of Self-Care Deficiency: A Case Report. J. Educ. Res. Nurs. 2022, 19, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, C.; Silva, M.; Cruz, I.; Cardoso, A.; Morais, E. Nursing diagnoses focused on universal self-care requisites. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2021, 68, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orem, D. Nursing: Concepts of Practice, 6th ed.; Mosby: Maryland Heights, MI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, S.; Haokip, L.; Liangkiuwiliu, R. Applicability of Orem’s self-care theory to practice—A narrative review. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2023, 8, 409–412. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Li, W.; Zhao, X.; Li, K. The cost-effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD in different settings: A systematic review. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2021, 19, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, H. Tradução, Adaptação e Validação do Self-Care In Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Inventory Para o Contexto Português. 2024. Available online: https://comum.rcaap.pt/handle/10400.26/52397 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Silva, L.; Maricoto, T.; Mota, Â.; Lemos, L.; Santos, M.; Cunha, H.; Padilha, J. Effectiveness of a home-based pulmonary rehabilitation maintenance programme: The Rehab2Life study protocol. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, C.; Alison, J.; Carlin, B.; Jenkins, A.; Cox, N.; Bauldoff, G.; Holland, A. Pulmonary rehabilitation for adults with chronic respiratory disease: An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, e7–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruit, M.; Singh, S.; Garvey, C.; ZuWallack, R.; Nici, L.; Rochester, C.; Wouters, E. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, e13–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, A.; Holland, A.; McDonald, C.; Abramson, M.; Hill, C.; Lee, A.; Mahal, A. Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD using minimal resources: An economic analysis. Respirology 2020, 25, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Dolezal, B.; Cooper, C. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Highly effective but often overlooked. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2020, 4, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wageck, B.; Cox, N.; Bondarenko, J.; Corbett, M.; Nichols, A.; Moore, R.; Holland, A. Early home-based pulmonary rehabilitation following acute exacerbation of COPD: A feasibility study using an action research approach. Chronic Respir. Dis. 2020, 17, 1479973120949207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Pu, Y.; Meng, A.; Zhi, X.; Xu, G. Effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation in elderly patients with COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2019, 25, e12745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, R.; Oliveira, H.; Goes, M.; Gonçalves, C.; Dias, A.; Fonseca, C. The effectiveness of nursing Reha-bilitation interventions on Self-Care for older adults with respiratory disorders: A systematic review with Me-ta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, D.C.H.; Gafni-Lachter, L. Addressing Barriers to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Care: Three Innovative Evidence-Based Approaches: A Review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2024, 19, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2024. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Hermiz, O.; Comino, E.; Marks, G.; Daffurn, K.; Wilson, S.; Harris, M. Randomised controlled trial of home based care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ 2002, 325, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coultas, D.; Frederick, J.; Barnett, B.; Singh, G.; Wludyka, P. A randomized trial of two types of nurse-assisted home care for patients with COPD. Chest 2005, 128, 2017–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawlor, M.; Kealy, S.; Agnew, M.; Korn, B.; Quinn, J.; Cassidy, C.; O’Donnell, R. Early discharge care with ongoing follow-up support may reduce hospital readmissions in COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2009, 4, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, M.; Grassi, M.; Pecis, M.; Andreoli, A.; Taurino, A.; Sergi, M.; Fanfulla, F. A specific home care program improves the survival of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease receiving long term oxygen therapy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 90, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, M.; Moyle, H.; Griffiths, S.; Shields, L. Outcomes of a home-based pulmonary maintenance program for individuals with COPD: A pilot study. Contemp. Nurse 2010, 34, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinci, A.; Olgun, N. The effectiveness of nurse-led, home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD in Turkey. Rehabil. Nurs. J. 2011, 36, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal Özkaptan, B.; Kapucu, S. Home nursing care with the self-care model improves self-efficacy of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2016, 13, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, C. Reducing COPD rehospitalizations. Home Healthc. Now 2020, 38, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, A.; Cox, N.; Houchen-Wolloff, L.; Rochester, C.; Garvey, C.; ZuWallack, R.; Singh, S. Defining modern pulmonary rehabilitation. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, e12–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranburu-Imatz, A.; López-Carrasco, J.; Moreno-Luque, A.; Jiménez-Pastor, J.; Valverde-León, M.; Rodríguez-Cortés, F.; Morales-Cané, I. Nurse-led interventions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, C.; Bianchi, C.; Vigna, M.; Crimi, C.; Mossolani, S.; Bucoveanu, V.; Carlucci, A. Effectiveness of an educational intervention on different types of errors occurring during inhaler therapy use in COPD patients during a Pulmonary Rehabilitation Program. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2024, 19, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, C.; Lista, A.; João, A.; António, A.; Bia, F. Rehabilitation Nursing on the Self-Management of the Elderly Person With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Rapid Review. Rev. Port. Enferm. Reabil. 2024, 72, e36446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oca, M.M.; Laucho-Contreras, M.E. Smoking cessation and vaccination. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 220187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, P.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Tang, L. The role of nurses in smoking cessation interventions for patients: A scoping review. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.; Collins, P.; Pavey, T.; Nguyen, N.; Pham, T.; Gallegos, D. Nutritional status, dietary intake, and health-related quality of life in outpatients with COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2019, 14, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, Y.; Tatsumi, H.; Takikawa, H.; Taniguchi, N.; Masuda, Y. Combined Effect of Early Nutrition Therapy and Rehabilitation for Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbation: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Huang, L.; Fang, Y.; Cai, S.; Zhang, M. Physical activity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A scoping review. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, E.; Posthuma, R.; Koopman, M.; Liu, W.; Sillen, M.; Hajian, B.; Franssen, F. An update on pulmonary rehabilitation techniques for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2020, 14, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2025. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2025-gold-report/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Poncin, W.; Schrøder, C.; Oliveira, A.; Herrero, B.; Cnockaert, P.; Gely, L.; Spinou, A. Airway clearance techniques for people with acute exacerbation of COPD: A scoping review. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2025, 34, 240191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingårdh, A.; Göransson, C.; Larsson, S.; Slinde, F.; Vanfleteren, L. Effectiveness of energy conservation techniques in patients with COPD. Respiration 2020, 99, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troosters, T.; Janssens, W.; Demeyer, H.; Rabinovich, R. Pulmonary rehabilitation and physical interventions. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 220222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaeh, S.; Case, M.; Au, D.; DaSilva, M.; Deitemeyer, K.; DeLisa, J.; Eakin, M. Clinical practices surrounding the prescription of home oxygen in patients with COPD and desaturation. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases. J. COPD Found. 2023, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, S.; Ali, S.; Abed, S.; Elasrag, G.; Ramadan, O. Effectiveness of standardized protocol for oxygen therapy on improving nurses’ performance and patients’ health outcome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugajski, A.; Szalacha, L.; Rechenberg, K.; Johnson, A.; Beckie, T.; Morgan, H. Psychometric Evaluation of the Self-Care in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Inventory in the United States. Heart Lung 2022, 51, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Putting People First in Managing Their Health: New WHO Guideline on Self-Care Interventions. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-06-2021-putting-people-first-in-managing-their-health-new-who-guideline-on-self-care-interventions (accessed on 25 November 2022).

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Participants: Elderly people (with a mean age of 65 years or older in the articles) diagnosed with COPD. | Studies that include people with other respiratory diseases such as asthma or that simultaneously cover people with COPD and other conditions. |

| Intervention: Studies in which at least one pulmonary rehabilitation intervention is carried out by a nurse at home. | Studies in which the interventions involve the use of devices or applications. Studies referring to home hospitalisation settings. |

| Comparator: Not applicable, as the adopted methodology allows the integration of studies with different methodological designs, thus not ensuring comparison between them. | |

| Outcomes: Studies in which the rehabilitation intervention in elderly individuals promotes:

|

| Search Strategy | N | |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | “Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive” OR “Pulmonary Emphysema” OR “Bronchitis, Chronic” OR “Lung Diseases, Obstructive” OR “Respiratory Tract Diseases” OR “copd” OR “chronic air flow obstruction” OR “Chronic Obstructive Airways Disease” | 134,196 |

| S2 | “Aged” OR “Geriatrics” OR “Gerontologic Nursing” OR “Gerontologic Care” OR “Older Adult Care” OR “Elderly” OR “Senior” OR “Elder” OR “Older” | 6,716,808 |

| S3 | “Ambulatory Care” OR “Ambulatory Care Information Systems” OR “Ambulatory Care Nursing” OR “American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing” OR “Community Programs” OR “Community Health Services” OR “Community Health Nursing” OR “Home Health Care” OR “Home Health Care Information Systems” OR “Home Respiratory Care” OR “Primary Health Care” OR “Primary Nursing” OR “Home Care Services” OR “Home Health Nursing” OR “Nurses, Community Health” OR “Primary Care Nursing” | 302,198 |

| S4 | “nurs*” | 1,232,767 |

| S5 | “Abdominal Exercises” OR “Aerobic Exercises” OR “American Association for Respiratory Care” OR “Association of Rehabilitation Nurses” OR “Breathing Exercises” OR “Drainage, Postural” OR “Endurance Training” OR “Exercise Tolerance” OR “Exercise” OR “Exercise Intensity” OR “Exercise Positions” OR “Exercise Therapy” OR “High-Intensity Interval Training” OR “Physical Education and Training” OR “Rehabilitation” OR “Warm-Up Exercise” OR “Rehabilitation Exercise” OR “Rehabilitation Nursing” OR “Rehabilitation Research” OR “Rehabilitation Patients” OR “Rehabilitation, Pulmonary” OR “Research, Rehabilitation” OR “Resistance Training” OR “Respiratory Therapy” OR “Telerehabilitation” OR “Therapeutic Exercise” OR “respiratory exercises” OR “Exercise training” OR “Exercise Programs” OR “Pulmonary rehab*” OR “Education” OR “Education, Pharmacy” OR “Health Education” OR “Education, Nursing” OR “Patient Education” OR “Education, Respiratory Therapy” OR “Patient Education as Topic” OR “Support, Psychosocial” OR “Psychosocial Aspects of Illness” OR “Rehabilitation, Psychosocial” OR “Psychosocial Care (Saba CCC)” OR “Psychosocial Support Systems” OR “Psychiatric Rehabilitation” OR “Psychosocial Intervention” OR “Nutritional Support” OR “Nutrition Therapy (Iowa NIC)” OR “Diet Therapy” OR “Diet” OR “Home Nutritional Support” OR “Nutritional Assessment” OR “Nutrition Support (Iowa NIC)” OR “Nutrition Therapy” | 3,454,187 |

| S6 | “Self-Care” OR “selfcare” OR “selfcare” OR “Self-Care Deficit (Saba CCC)” OR “Self-Care Component (Saba CCC)” OR “Self-Care Assistance: Dressing-Grooming (Iowa NIC)” OR “Self-Care Assistance: Bathing-Hygiene (Iowa NIC)” OR “Self-Care Agency OR Self-Care: Instrumental” OR “Activities of Daily Living (Iowa NOC)” OR “Self-Care: Toileting (Iowa NOC)” OR “Self-Care: Parenteral Medication (Iowa NOC)” OR “Self-Care: Oral Hygiene (Iowa NOC)” OR “Self-Care: Activities of Daily Living (Iowa NOC)” OR “Activities of Daily Living” OR “Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Alteration (Saba CCC)” OR “Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (Saba CCC)” OR “Activities of Daily Living Alteration (Saba CCC)” OR “Activities of Daily Living (Saba CCC)” OR “Functional Status” OR “Geriatric Functional Assessment” OR “Geriatric Assessment” OR “functional*” OR “Functional capacity” OR “Physical Functional Performance” | 2,325,775 |

| S1 AND S2 AND S3 AND S4 AND S5 AND S6 | 47 |

| Search Strategy | N | |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive OR Pulmonary Emphysema OR Bronchitis, Chronic OR Lung Diseases, Obstructive OR Respiratory Tract Diseases OR copd OR chronic air flow obstruction OR Chronic Obstructive Airways Disease | 48,900 |

| S2 | Aged OR Geriatrics OR Gerontologic Nursing OR Gerontologic Care OR Older Adult Care OR Elderly OR Senior OR Elder OR Older | 1,302,092 |

| S3 | Ambulatory Care OR Ambulatory Care Information Systems OR Ambulatory Care Nursing OR American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing OR Community Programs OR Community Health Services OR Community Health Nursing OR Home Health Care OR Home Health Care Information Systems OR Home Respiratory Care OR Primary Health Care OR Primary Nursing OR Home Care Services OR Home Health Nursing OR Nurses, Community Health OR Primary Care Nursing | 232,598 |

| S4 | nurs* | 1,017,896 |

| S5 | Abdominal Exercises OR Aerobic Exercises OR American Association for Respiratory Care OR Association of Rehabilitation Nurses OR Breathing Exercises OR Drainage, Postural OR Endurance Training OR Exercise Tolerance OR Exercise OR Exercise Intensity OR Exercise Positions OR Exercise Therapy OR High-Intensity Interval Training OR Physical Education and Training OR Rehabilitation OR Warm-Up Exercise OR Rehabilitation Exercise OR Rehabilitation Nursing OR Rehabilitation Research OR Rehabilitation Patients OR Rehabilitation, Pulmonary OR Research, Rehabilitation OR Resistance Training OR Respiratory Therapy OR Telerehabilitation OR Therapeutic Exercise OR respiratory exercises OR Exercise training OR Exercise Programs OR Pulmonary rehab* OR Education OR Education, Pharmacy OR Health Education OR Education, Nursing OR Patient Education OR Education, Respiratory Therapy OR Patient Education as Topic OR Support, Psychosocial OR Psychosocial Aspects of Illness OR Rehabilitation, Psychosocial OR Psychosocial Care (Saba CCC) OR Psychosocial Support Systems OR Psychiatric Rehabilitation OR Psychosocial Intervention OR Nutritional Support OR Nutrition Therapy (Iowa NIC) OR Diet Therapy OR Diet OR Home Nutritional Support OR Nutritional Assessment OR Nutrition Support (Iowa NIC) OR Nutrition Therapy | 1,427,749 |

| S6 | Self-Care OR selfcare OR self-care OR Self-Care Deficit (Saba CCC) OR Self-Care Component (Saba CCC) OR Self-Care Assistance: Dressing-Grooming (Iowa NIC) OR Self-Care Assistance: Bathing-Hygiene (Iowa NIC) OR Self Care Agency OR Self-Care: Instrumental OR Activities of Daily Living (Iowa NOC) OR Self-Care: Toileting (Iowa NOC) OR Self-Care: Parenteral Medication (Iowa NOC) OR Self-Care: Oral Hygiene (Iowa NOC) OR Self Care: Activities of Daily Living (Iowa NOC) OR Activities of Daily Living OR Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Alteration (Saba CCC) OR Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (Saba CCC) OR Activities of Daily Living Alteration (Saba CCC) OR Activities of Daily Living (Saba CCC) OR Functional Status OR Geriatric Functional Assessment OR Geriatric Assessment OR functional* OR Functional capacity OR Physical Functional Performance | 355,165 |

| S1 AND S2 AND S3 AND S4 AND S5 AND S6 | 50 |

| Author, Year, and Country | Aim Study Design | Participants | Pulmonary Rehabilitation Intervention | Professionals Involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (Age ± SD) (Men/Women) | ||||

| [27] (2002) Australia | To evaluate the usefulness of limited community-based care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) after discharge from the hospital. RCT |

| Patient Education on COPD: Comprehensive education on the disease, focusing on its pathophysiology, progression, and management strategies to enhance self-management and adherence to care. Smoking Cessation Counselling: Guidance on the importance of quitting smoking, including verbal and written support, as smoking cessation is critical to reducing disease progression and exacerbations. Management of Activities of Daily Living (ADLs): Education on safe and efficient strategies for performing ADLs, aiming to reduce physical strain and improve functional independence. Energy Conservation Techniques: Training in methods to conserve energy during daily activities, such as pacing, task prioritisation, and the use of adaptive tools. Medication Education and Adherence: Detailed instruction on the correct use of prescribed medications, particularly inhalers, and the importance of adherence to pharmacological treatment to control symptoms and prevent exacerbations. Physical Exercise: Guidance on incorporating safe and tailored physical exercises to improve respiratory function and overall endurance, aligned with the patient’s limitations. Early Recognition of Complications: Education on identifying early signs of complications or exacerbations that require medical intervention, promoting timely care-seeking behaviour. | Community nurses |

| [28] (2005) United States | The study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of increasing access to selected components of pulmonary rehabilitation—namely, patient education, self-management skill improvement, and enhanced follow-up—through nurse-assisted home care. RCT |

| Reassessment of Symptoms and Pharmacological Therapy: Conducted at the time of discharge to ensure the patient’s treatment plan is optimised and aligned with their clinical status. Patient Education: Focused on the disease (COPD), including symptom recognition and the appropriate use of prescribed medications. Smoking Cessation Counselling: Providing guidance and support to encourage and sustain smoking cessation. Development of a Written Action Plan: Prepared at discharge to guide patients in managing exacerbations effectively. Communication with the Patient’s Primary Care Physician: Writing a detailed letter to the family physician with updates on the patient’s condition and suggested management adjustments. Home-Based Patient Assessment: Evaluating the patient’s clinical status and environmental factors during home visits. Telephone Follow-Ups: Conducted at least once a month to monitor symptoms, provide guidance, and address any emerging concerns. | Nurses |

| [29] (2009) Ireland | The study aimed to evaluate the impact of a disease-specific home care (HC) programme on survival, exacerbation rates, and hospital admissions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) requiring long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT), compared to standard care (SC).Cohort Study | Early discharge programme:

| Disease Education: Provide comprehensive education about chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), focusing on its pathophysiology, progression, and impact on daily life. Smoking Cessation Counselling: Deliver targeted interventions to encourage and support smoking cessation, emphasising its critical role in disease management and stabilisation. Device Management: Educate patients on the correct use and maintenance of respiratory devices, including inhalers, nebulizers, and oxygen equipment, ensuring optimal therapeutic outcomes. Medication Monitoring and Collaboration: Collaborate with the medical team to monitor the patient’s condition and communicate any clinical changes that may require adjustments to treatment; support patients in adhering to prescribed medication regimens and educate them on the proper use, timing, and potential side effects of their medications. Chest Physiotherapy: Implement airway clearance techniques to improve ventilation, optimise lung function, and promote respiratory health. Individualised Home Exercise Programme: Develop and provide tailored exercise plans to enhance physical capacity and respiratory efficiency, designed according to the patient’s functional status and capabilities. Self-Management Plan: Collaborate with patients to create a personalised self-management plan, which includes recognising early symptoms of exacerbation; instructions on medication adjustments during exacerbations (e.g., self-administration of antibiotics, steroids, and bronchodilators); sputum clearance techniques; written guidance for early intervention; and strategies to prevent hospitalizations. Ongoing Monitoring and Rapid Access to Care: Ensure patients have scheduled follow-up appointments and maintain rapid access to respiratory outpatient clinics for timely evaluation and intervention during exacerbations. Telephone Support: Provide patients with access to telephone support for advice and reassurance, particularly during exacerbations, helping to address their concerns promptly and effectively. | Respiratory nurses; physiotherapists; and respiratory physicians |

| [30] (2009) Italy | The study aimed to evaluate the impact of a disease-specific home care (HC) programme on survival, exacerbation rates, and hospital admissions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) requiring long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT), compared to standard care (SC). Cohort Study |

66 ± 12 (SC).

65% M (SC). | Disease Education: Educating patients and caregivers about chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), its progression, and management. Risk Factor Control: Reducing exposure to passive smoking, indoor and outdoor pollution, and infection risks. Body Weight Control: Supporting patients in maintaining an appropriate body weight to optimise respiratory function and overall health. Device Management: Training in the correct use and maintenance of medical devices, including oxygen therapy equipment. Medication Management: Supporting proper administration of medications, adherence to prescribed therapies, and adjustment when needed. Oxygen Administration Management: Ensuring correct use and compliance with long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT). Bronchial Drainage Techniques: Employing methods such as autogenic drainage, Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) mask, and expiration with the glottis open in the lateral posture (ELTGOL). Inspiratory Muscle Training: Implementing exercises to strengthen respiratory muscles, improving ventilation efficiency. Physical Training: Designing and guiding exercise programmes tailored to the patient’s needs, enhancing physical capacity and quality of life. | Respirator nurses, pneumologists, and rehabilitation therapists |

| [31] (2010 Australia | The study aimed to generate preliminary data to inform the design of a larger trial investigating the effects of the pulmonary maintenance programme on self-efficacy; functional exercise capacity; respiratory functioning; and quality of life in COPD patients. Quasi-Experimental Study |

| Collaborative Goal Setting: Nurses played a pivotal role in establishing individualised goals with the patient during the initial home visit. These goals were reviewed and adjusted at six and twelve months, ensuring alignment with the patient’s progress and evolving needs. Scheduled Telephone Follow-Ups: Nurses conducted regular telephone calls to monitor patient progress, provide tailored guidance, and reinforce adherence to the programme. These calls were scheduled weekly during the first month, and subsequently at two, five, eight, and ten months. Patient Education: Nurses provided continuous education on self-management strategies, disease progression, and techniques for preventing exacerbations. This education empowered patients to manage their condition more effectively and maintain the benefits of respiratory rehabilitation. Assessment of Symptom Perception and Functional Limitations: Nurses participated in monitoring functional and respiratory capacity using tools such as the Medical Research Council (MRC) Dyspnoea Scale and the Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS). These assessments, conducted in collaboration with physiotherapists, tracked progress and identified any clinical changes. Psychosocial Support: Nurses addressed the emotional and psychological needs of patients, providing psychosocial support to alleviate anxiety and depression associated with COPD. This approach contributed to improved adherence and overall well-being. Promotion of Self-Efficacy: Nurses played a crucial role in promoting patients’ confidence in managing their respiratory challenges, adhering to the maintenance program, and performing daily activities. This intervention was embedded in telephone follow-ups and face-to-face interactions. Supervised Exercise Programme: Nurses were actively involved in supervising and encouraging adherence to the structured exercise program, which included warm-up exercises, preparing patients for more intense physical activity and reducing the risk of injury; strength training, focusing on muscle strengthening to enhance functional capacity; balance exercises aimed at improving stability and reducing the risk of falls; and stretching, promoting flexibility and preventing muscular stiffness. Nurses ensured correct and safe execution of these exercises during telephone follow-ups and in-person visits, supporting progression throughout the 12-month program. | Nurses and physiotherapists |

| [32] (2011) Turkey | To evaluate the impact of a nurse-led, home-based pulmonary rehabilitation programme on pulmonary function, arterial blood gases, quality of life, dyspnoea, and functional capacity in patients with advanced COPD. Quasi-Experimental Study |

| Patient Education: Educational sessions were conducted 2–3 times in patients’ homes, lasting 2–3 h per session; information was provided both verbally and in pamphlets tailored to the patients’ specific symptoms. The content included the following: anatomy and physiology of the lungs; airway changes caused by COPD; causes and symptoms of the disease; instructions for the correct use of inhaled medications; breathing exercises, including pursed-lip and diaphragmatic breathing techniques; relaxation and breathing control methods; airway clearance techniques; modifications to daily living activities and energy conservation strategies; exercise recommendations; and smoking cessation methods. Nurses provided individualised education based on the patient’s needs, monitored comprehension, and distributed printed materials. Exercise Programme: The exercise programme included three components: Lower Extremity Aerobic Exercise (patients were instructed to walk for 30 min daily, adjusting the pace to their individual abilities) and Upper Extremity Aerobic Exercise (a variety of arm exercises were performed, each for 15 repetitions per set, with each set lasting at least 1 min). Examples of exercises included the following: stirring the soup in a cauldron; pulling up the anchor; hitting the punching bag; rowing the boat; marching arm movements; punching; waxing the car (“wax on, wax off”); performing the crawl and breaststroke movements; playing the drums and accordion; chopping wood; picking cherries; pulling weeds; wiping the windshield; stretching the springs; and scissoring the arms. Patients could complete exercises in intervals if needed. Breathing Exercises: Pursed-lip breathing and diaphragmatic breathing were practiced for 30 min each day. Nurses demonstrated these exercises during the first session and provided ongoing supervision. Home-Based Implementation and Monitoring: Patients were instructed to perform the prescribed exercises independently at home and to maintain a record of any challenges encountered. Nurses monitored progress and adherence through follow-up visits, where exercise performance was evaluated; addressing challenges identified during the visits and correcting improper exercise techniques; and phone calls made every 15 days during the first month and monthly in subsequent months to ensure adherence. Supervision and Evaluation: During the second and third home visits, nurses observed patients performing the exercises, evaluated their execution, and addressed any issues identified. Nurses played a key role in reinforcing the correct techniques for breathing and physical exercises to optimise outcomes. | Nurses |

| [33] (2016) Turkey | The primary aim was to determine whether home nursing care based on Orem’s self-care model enhances the self-efficacy of patients with COPD. The secondary goal was to assess the impact of this intervention on symptom management, including dyspnoea and related complications. Quasi-Experimental Study | The study involved 106 patients diagnosed with COPD in northern Turkey. The participants were divided into two groups: intervention (n = 53) and control (n = 53).

| Education about COPD: Educate patients and their families about the definition, causes, symptoms, and diagnostic methods of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); this information was provided during home visits and through the distribution of an educational guide developed specifically for patients and their families. Guidance on COPD Management: Provide strategies for managing COPD symptoms, including techniques to alleviate dyspnoea, reduce fatigue, and improve activity tolerance; these strategies were integrated into the individualised care plans developed during the home visits. Nutritional Counselling: Offer guidance on proper nutrition to prevent imbalanced nutrition and ensure patients meet their dietary needs, as outlined in the care plan. Respiratory Exercises: Teach and supervise patients in performing diaphragmatic breathing and pursed-lip breathing to improve respiratory efficiency and control dyspnoea; these exercises were explicitly mentioned in the educational guide and reinforced during home visits. Smoking Cessation Support: Educate and motivate patients to quit smoking, emphasising its role in slowing disease progression and improving quality of life; smoking cessation was a key focus in the educational materials provided to patients. Medication Adherence: Educate patients on the importance of regular and effective use of prescribed medications for symptom control and disease management; this topic was addressed during the educational sessions as part of the care plan. Prevention of Respiratory Infections: Provide education on protecting the upper respiratory system from infections, including hygiene practices and effective coughing techniques; these strategies were included in the educational guide distributed to patients and families. Emotional and Psychological Support: Offer support to patients experiencing anxiety or psychological distress due to COPD, improving their emotional state and motivation for self-care; emotional support was part of the holistic approach to care provided during home visits. | Nurses |

| [34] (2020) United States | The primary purpose of the study was to assess whether the implementation of a COPD self-management care plan packet in home healthcare could reduce the rate of 30-day rehospitalizations among patients with COPD. Secondary objectives included improving COPD symptom management and medication reconciliation rates, as well as promoting timely follow-up with healthcare providers. Quasi-Experimental Study |

| Identification of Patient-Specific Learning Needs: Nurses used a daily form to assess and document patient-specific learning needs, such as adherence to prescribed medication therapy, including oxygen therapy; dietary and lifestyle modifications to manage symptoms; and smoking cessation. This form was designed to support daily self-management and was reviewed during each nursing visit to adjust care plans based on the patient’s progress. Educational Interventions Through Informative Handouts: Educational sessions were conducted by nurses using targeted handouts that focused on key aspects of COPD self-management: the purpose and proper technique for using inhalers; safety guidelines for oxygen therapy; and smoking cessation education to encourage and support patients in quitting smoking. Lifestyle and Symptom Management Education: Nurses provided additional educational materials and guidance to patients, addressing lifestyle modifications and symptom management strategies; identifying and avoiding symptom triggers; performing deep breathing exercises to improve respiratory function; engaging in daily activities as tolerated by the patient’s physical condition; maintaining a healthy and balanced diet to support overall well-being; and recognising and managing anxiety and/or depression, which are often associated with COPD. These materials were stored in the patient’s home for daily use and were reviewed during nursing visits to ensure proper application. Development of a COPD-Specific Action Plan: Nurses collaborated with patients to create a COPD action plan, which included the following: a daily symptom log for tracking symptoms and oxygen saturation levels; instructions categorised into “zones” (green for controlled symptoms, yellow for worsening symptoms, and red for emergent symptoms) to guide patient decision-making. The action plan empowered patients to manage their symptoms effectively and provided clear instructions for seeking help when symptoms worsened. Medication Reconciliation: During admission, nurses conducted a thorough medication reconciliation to ensure accuracy in prescribed COPD medications and addressed any deficiencies. Coordination of Timely Follow-Up Care: Nurses ensured that patients had follow-up appointments scheduled with their primary care providers or pulmonologists within one week of hospital discharge, promoting continuity of care and reducing readmission risks. Reinforcement of COPD Self-Management During Visits: During each nursing visit, nurses reviewed the patient’s self-management progress; the materials and action plans provided during previous sessions; and proper inhaler techniques, lifestyle modifications, and symptom management strategies. Assessment of COPD Symptoms Using the COPD Assessment Test (CAT): Nurses utilised the CAT tool to assess the severity of COPD symptoms during admission and discharge. The results were used to evaluate the patient’s risk of readmission and the effectiveness of the interventions. | Nurses |

| Lawlor et al., (2009) [29] | Rizzi et al., (2009) [30] | |

|---|---|---|

| Were the two groups similar and recruited from the same population? | YES | YES |

| Were the exposures measured similarly to assign people to both exposed and unexposed groups? | YES | YES |

| Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | YES | YES |

| Were confounding factors identified? | NO | YES |

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | NO | YES |

| Were the groups/participants free of the outcome at the start of the study (or at the moment of exposure)? | YES | YES |

| Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | YES | YES |

| Was the follow-up time reported and sufficient to be long enough for outcomes to occur? | YES | YES |

| Was follow-up complete, and if not, were the reasons for loss to follow-up described and explored? | YES | YES |

| Were strategies used to address incomplete follow-up? | NO | YES |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | YES | YES |

| Hermiz et al. (2002) [27] | Coultas et al. (2005) [28] | |

|---|---|---|

| Was true randomization used for the assignment of participants to treatment groups? | YES | YES |

| Was allocation to treatment groups concealed? | NO | NO |

| Were treatment groups similar at the baseline? | YES | YES |

| Were participants blind to treatment assignment? | NO | NO |

| Were those delivering the treatment blind to treatment assignment? | NO | NO |

| Were treatment groups treated identically other than the intervention of interest? | NO | YES |

| Were outcome assessors blind to treatment assignment? | Unclear | YES |

| Were outcomes measured in the same way for treatment groups? | YES | YES |

| Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | YES | YES |

| Was follow up complete, and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow up adequately described and analysed? | YES | YES |

| Were participants analysed in the groups to which they were randomised? | YES | YES |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | YES | YES |

| Was the trial design appropriate and any deviations from the standard RCT design (individual randomization, parallel groups) accounted for in the conduct and analysis of the trial? | No | Yes |

| Cooke et al., (2009) [31] | Akinci et al., (2011) [32] | Bal Özkaptan et al., (2016) [33] | McGill et al., (2020) [34] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is it clear in the study what is the “cause” and what is the “effect” (i.e., there is no confusion about which variable comes first)? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Was there a control group? | NO | YES | YES | NO |

| Were participants included in any similar comparisons? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Were the participants included in any comparisons receiving similar treatment/care other than the exposure or intervention of interest? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Were there multiple measurements of the outcome, both pre- and post-intervention/exposure? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Were the outcomes of participants included in any comparisons measured in the same way? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Were outcomes measured in a reliable way? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Was follow-up complete and if not, were differences between groups in terms of their follow-up adequately described and analysed? | NO | NO | YES | NO |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| [27] | [28] | [29] | [30] | [31] | [32] | [33] | [34] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Education | About the condition | ✓ | ✓ | M | M | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Correct use of medication (especially inhalers) | ✓ | ✓ | M | M | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Smoking cessation | ✓ | ✓ | M | M | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Symptom and exacerbation management | ✓ | ✓ | M | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Nutritional counselling | ✓ | M | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Respiratory Training and Physical Exercise | Only education on physical exercise | ✓ | |||||||

| Aerobic and/or strength training | M | M | ✓ | ||||||

| Respiratory exercises | M | M | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Airway clearance techniques | M | M | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Education about energy conservation techniques | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Tailor-Made Plan, Monitoring, and Follow-up | ✓ | ✓ | M | M | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Psychological Support | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Oxygen Therapy Management | M | M | ✓ | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salvado, S.; Grilo, E.; Henriques, H.; Ferraz, I.; Gaspar, F.; Baixinho, C. Pulmonary Rehabilitation Nursing Interventions Promoting Self-Care in Elderly People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (At Home). Healthcare 2025, 13, 2176. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172176

Salvado S, Grilo E, Henriques H, Ferraz I, Gaspar F, Baixinho C. Pulmonary Rehabilitation Nursing Interventions Promoting Self-Care in Elderly People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (At Home). Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2176. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172176

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalvado, Susana, Eugénia Grilo, Helga Henriques, Isabel Ferraz, Filomena Gaspar, and Cristina Baixinho. 2025. "Pulmonary Rehabilitation Nursing Interventions Promoting Self-Care in Elderly People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (At Home)" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2176. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172176

APA StyleSalvado, S., Grilo, E., Henriques, H., Ferraz, I., Gaspar, F., & Baixinho, C. (2025). Pulmonary Rehabilitation Nursing Interventions Promoting Self-Care in Elderly People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (At Home). Healthcare, 13(17), 2176. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172176