Level of Awareness About Dental Veneers and Their Oral Hygiene Care Among the General Saudi Public: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Date

2.2. Study Population and Target Group

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Sampling Technique

2.5. Outcome Assessment

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thomas, P.A.; Krishnamoorthi, D.; Mohan, J.; Raju, R.; Rajajayam, S.; Venkatesan, S. Digital Smile Design. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2022, 14 (Suppl. S1), S43–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theobald, A.H.; Wong, B.K.; Quick, A.N.; Thomson, W.M. The impact of the popular media on cosmetic dentistry. N. Z. Dent. J. 2006, 102, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pini, N.P.; Aguiar, F.H.; Lima, D.A.; Lovadino, J.R.; Terada, R.S.; Pascotto, R.C. Advances in dental veneers: Materials, applications, and techniques. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2012, 4, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El-Mowafy, O.; El-Aawar, N.; El-Mowafy, N. Porcelain veneers: An update. Dent. Med. Probl. 2018, 55, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassler, H.E. Minimally invasive porcelain veneers: Indications for a conservative esthetic dentistry treatment modality. Gen. Dent. 2007, 55, 686–694; quiz 695–696, 712. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, S.; Albanesi, R.B.; Sesma, N.; Agra, C.M.; Braga, M.M. Main Clinical Outcomes of Feldspathic Porcelain and Glass-Ceramic Laminate Veneers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Survival and Complication Rates. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2016, 29, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alothman, Y.; Bamasoud, M.S. The Success of Dental Veneers According To Preparation Design and Material Type. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 2402–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.W.; Tan, S.K.; Li, K.Y.; Burrow, M.F. Survival and complication rates of resin composite laminate veneers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Evid.-Based Dent. Pract. 2023, 23, 101911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asaad, R.S.; Alshwaer, A.A.; Alahmadi, S.A.; Alyamani, M.H.; Alshaeri, R.M. Awareness of the population about ceramic laminate veneers in Saudi Arabia. Curr. Sci. Int. 2019, 8, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi, D.; Aboalshamat, K.; Salem, A.; Binmahfouz, S.; Alghamdi, A.; Hassan, S.; Aljohani, A.; Mohammed, R. Level of Awareness of the population about dental veneers in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Res. Med. Dent. Sci. 2020, 8, 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Alshammery, F.; Alkanhal, N.A.; Alabdulkarim, A.S.; Alfaqeeh, S.A.; Alshammery, D.A.; Alotaibi, A.A.; Alshammery, S. Awareness among a convenient sample of Riyadh city population toward dental veneers. J. Appl. Dent. Med. Sci. 2020, 6, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aljehani, W.A.; Alharbi, A.A.; Alharbi, A.T.; Alharbi, A.A.; Alharbi, M.A.; ALanazi, A.O.; Alharbi, A.L. Measuring the awareness, knowledge, and practice of the patients using veneer and lumineers and its effect on periodontium: A cross sectional study in Al-Qassim region. Int. J. Med. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 4, 347. [Google Scholar]

- Vallittu, P.K.; Vallittu, A.S.; Lassila, V.P. Dental aesthetics—A survey of attitudes in different groups of patients. J. Dent. 1996, 24, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alfouzan, A.; Al-Sanie, A.A.; Al-Dhafiri, R.A. Arab Societal Awareness of Dental Veneers. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2018, 19, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tin-Oo, M.M.; Saddki, N.; Hassan, N. Factors influencing patient satisfaction with dental appearance and treatments they desire to improve aesthetics. BMC Oral Health 2011, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samorodnitzky-Naveh, G.R.; Grossman, Y.; Bachner, Y.G.; Levin, L. Patients’ self-perception of tooth shade in relation to professionally objective evaluation. Quintessence Int. 2010, 41, e80–e83. [Google Scholar]

- Aristidis, G.A.; Dimitra, B. Five-year clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers. Quintessence Int. 2002, 33, 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- More, A.B.; Rodrigues, A.; Sadhu, B.J. Effects of smoking on oral health: Awareness among dental patients and their attitude towards its cessation. Indian. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 32, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaleb, A.Q.M.; Albader, R.A.; Alfahad, M.A.; AlGhizzi, M.G.M.; Aldhuwayhi, S.; Mustafa, M.Z.; Thakare, A.A.; Naqvi, Z.A. Knowledge, Awareness, and Practice of Gingival Veneer Prosthesis Among Dental Students, Interns, and Practitioners in the Riyadh Region: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire-Based Survey. Available online: https://opendentistryjournal.com/VOLUME/16/ELOCATOR/e187421062111172/FULLTEXT/ (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Al-Shorman, H.M.; Abu-Naba’a, L.A.; Sghaireen, M.G.; Alam, M.K. The Effect of Various Preparation and Cementation Techniques of Dental Veneers on Periodontal Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Dent. 2024, 18, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, A.A.; Abdulbaqi, H.R.; Alshami, M.L.; Al-Rawi, N.H. Oral health awareness, attitude towards dental treatment, fear of infection and economic impact during COVID-19 pandemic in the Middle East. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2021, 19, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, N.A.; Meyad, F.H.; Al-Abdallah, M.M.; Abu-Awwad, M.; Satterthwaite, J.D. Knowledge and awareness of dental implants among Syrian refugees: A cross sectional study in Zaatari camp. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haj Husain, A.; De Cicco, O.; Stadlinger, B.; Bosshard, F.A.; Schmidt, V.; Özcan, M.; Valdec, S. A Survey on Attitude, Awareness, and Knowledge of Patients Regarding the Use of Dental Implants at a Swiss University Clinic. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadin, A.; Badrov, M. Oral Health Knowledge, Self-Assessed Oral Health Behavior, and Oral Hygiene Practices among the Adult General Population in Croatia. Healthcare 2023, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Aher, V.; Lath, P.; Khangembam, M.; Nishant; Pani, P.; Singh, U. Knowledge and awareness of dental implants as a treatment choice in the adult population in North India: A hospital-based study. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 12, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K., Jr.; Kaur, N., 2nd; Kaur, G., 3rd; Garg, U.t. Knowledge, Awareness, and Attitude in Using Dental Implants as an Option in Replacing Missing Teeth Among Dental Patients: Survey-Based Research in a Dental Teaching Hospital in Derabassi, Punjab. Cureus 2022, 14, e27127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, I.; Krüger, K.; Jockusch, J. Age-related knowledge deficit and attitudes towards oral implants: Survey-based examination of the correlation between patient age and implant therapy awareness. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, H.; Ishak, N.; Yacob, N.; Ali, W.W. Self-Perceived Oral Health and Awareness on Replacement of Missing Teeth among Patients at a Public University. J. Int. Dent. Med. Res. 2021, 14, 309–314. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, H.Y.; Roccuzzo, A.; Stähli, A.; Salvi, G.E.; Lang, N.P.; Sculean, A. Oral health-related quality of life of patients rehabilitated with fixed and removable implant-supported dental prostheses. Periodontol. 2000 2022, 88, 201–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, M.; Pellegrini, M.; Rigoni, M.; Veronesi, V.; Beretta, M.; Maiorana, C.; Poli, P.P. Oral health-related quality of life in implant-supported rehabilitations: A prospective single-center observational cohort study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuya, J.; Suzuki, H.; Hidaka, R.; Koshitani, N.; Motomatsu, Y.; Kabasawa, Y.; Tohara, H.; Sato, Y.; Minakuchi, S.; Miyake, S. Factors affecting the oral health of inpatients with advanced cancer in palliative care. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halboub, E.; Al-Ak’hali, M.S.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Abdulghani, E.A.; Kamil, M.A.; Alhajj, M.N.; Al-Sosowa, A.A. Quality of web-based Arabic health information on dental implants: An infodemiological study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, P.; Spalthoff, S.; Korn, P.; Stoetzer, M.; Gercken, M.; Gellrich, N.C.; Rahlf, B. Oral health-related quality of life in tumour patients treated with patient-specific dental implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, A.; Keraa, K.; Farghaly, M.M. The impact of oral health literacy on dental anxiety and utilization of oral health services among dental patients: A cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, M.C.; Hopcraft, M.S.; Darby, I.B. Dental Implant Hygiene and Maintenance Protocols: A survey of oral health practitioners in Australia. Am. Dent. Hyg. Assoc. 2021, 95, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Samman, M.; Tashkandi, A.; Alsharif, M.; Ashi, H.; Bahanan, L. User Insights into Fake Snap-on Veneers: Perceptions and Experiences. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2024, 16, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belead, R.; Tawati, R.; Mohamed, A.; Bogazia, S. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Dental Practitioners Toward Laminate Veneer Preparation in Benghazi, Libya. AlQalam J. Med. Appl. Sci. 2025, 8, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Pavalan, A.; Pitru, A.R.; Gheorghe, D.N.; Florescu, C.; Popescu, D.M.; Rîcă, A.M.; Nicolae, F.; Turcu, A.A.; Surlin, P. An Assessment of Periodontal Status and Oral Hygiene in Patients with Hypertension in the South-West Region of Romania. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | N = 340 |

|---|---|

| Age (Years), n (%) | |

| 18–24 | 66 (19.4%) |

| 25–34 | 68 (20.0%) |

| 35–44 | 111 (32.6%) |

| 45–54 | 82 (24.1%) |

| 55 and more | 13 (3.8%) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 275 (80.9%) |

| Male | 65 (19.1%) |

| Nationality, n (%) | |

| Non-Saudi | 11 (3.2%) |

| Saudi | 329 (96.8%) |

| Which region do you live in? n (%) | |

| Western Region | 120 (35.3%) |

| Central Region | 88 (25.9%) |

| Eastern Region | 58 (17.1%) |

| Southern Region | 50 (14.7%) |

| Northern Region | 24 (7.1%) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 237 (69.7%) |

| Single | 103 (30.3%) |

| Educational level, n (%) | |

| Medium and less | 12 (3.5%) |

| High school | 69 (20.3%) |

| Graduate | 22 (6.5%) |

| Academic | 237 (69.7%) |

| Do you work in the dental field, n (%) | |

| No | 321 (94.4%) |

| Yes | 19 (5.6%) |

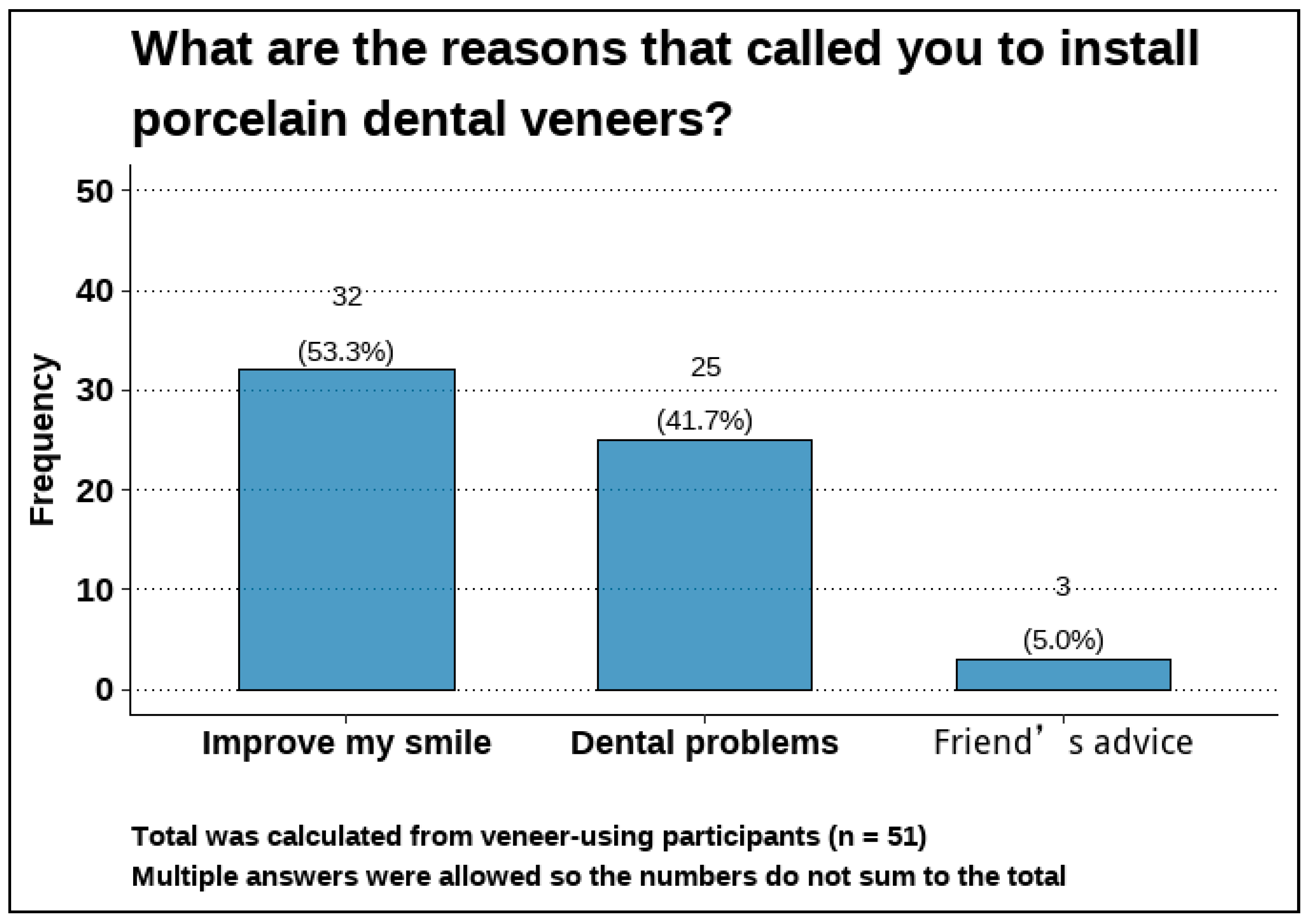

| Did you have veneers, n (%) | |

| No | 289 (85.0%) |

| Yes | 51 (15.0%) |

| How did you hear about dental veneers, n (%) a | |

| Dentist’s recommendation | 165 (48.5%) |

| Advertisements | 141 (41.5%) |

| Talking to people | 108 (31.8%) |

| Internet search | 88 (25.9%) |

| Social media platforms | 51 (15.0%) |

| Television | 47 (13.8%) |

| Question | More than Twice a Day | Twice Daily | Once a Day | Less than Once a Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How many times do you brush your teeth before installing the porcelain dental veneers? a | 9 (17.6%) | 26 (51.0%) | 13 (25.5%) | 3 (5.9%) |

| How many times do you brush your teeth after installing the porcelain dental veneers? a | 15 (29.4%) | 23 (45.1%) | 10 (19.6%) | 3 (5.9%) |

| Do you use mouthwash? a | 4 (7.8%) | 9 (17.6%) | 17 (33.3%) | 21 (41.2%) |

| Characteristic | N = 340 |

|---|---|

| Do you use dental floss or water floss before installing the porcelain dental veneers, n (%) a | |

| Yes | 17 (33.3%) |

| Sometimes | 16 (31.4%) |

| No | 17 (33.3%) |

| I’ve never heard of dental floss or water floss | 1 (2.0%) |

| Do you use dental floss or water floss after installing the porcelain dental veneers, n (%) a | |

| Yes | 17 (33.3%) |

| Sometimes | 16 (31.4%) |

| No | 17 (33.3%) |

| I’ve never heard of dental floss or water floss | 1 (2.0%) |

| Were you given instructions after the installation of dental veneers by the dentist or assistant, n (%) a | |

| No | 15 (29.4%) |

| Yes | 36 (70.6%) |

| Do you think that smoking or drinking a lot of coffee affects the veneers, n (%) | |

| Affects, but with the right preservation, it can be avoided | 94 (27.6%) |

| No | 28 (8.2%) |

| Yes | 218 (64.1%) |

| Do you think that when you install the dental veneers, it keeps you away from cleaning your teeth, n (%) | |

| No | 313 (92.1%) |

| Yes | 27 (7.9%) |

| Characteristic | N = 340 |

|---|---|

| When do you think dental veneers are indicated, n (%) | |

| Badly stained teeth not responding to bleaching, n (%) | |

| No | 87 (25.6%) |

| Yes * | 253 (74.4%) |

| Correction of severely crowded teeth, n (%) | |

| No * | 144 (42.4%) |

| Yes | 196 (57.6%) |

| Replace missing teeth, n (%) | |

| No * | 118 (34.7%) |

| Yes | 222 (65.3%) |

| Anterior fractured teeth, n (%) | |

| No | 118 (34.7%) |

| Yes * | 222 (65.3%) |

| Multiple stained anterior restorations, n (%) | |

| No | 87 (25.6%) |

| Yes * | 253 (74.4%) |

| Dental fluorosis, n (%) | |

| No | 104 (30.6%) |

| Yes * | 236 (69.4%) |

| What are the considered benefits of dental veneers, n (%) | |

| Change tooth color, n (%) | |

| No | 62 (18.2%) |

| Yes * | 278 (81.8%) |

| Resist coffee/tea/smoking stains, n (%) | |

| No | 120 (35.3%) |

| Yes * | 220 (64.7%) |

| Do not require teeth brushing and flossing? n (%) | |

| No * | 270 (79.4%) |

| Yes | 70 (20.6%) |

| Change the tooth shape? n (%) | |

| No | 64 (18.8%) |

| Yes * | 276 (81.2%) |

| Prevent tooth decay/care? n (%) | |

| No * | 199 (58.5%) |

| Yes | 141 (41.5%) |

| Closure of the slight spaces between teeth? n (%) | |

| No | 39 (11.5%) |

| Yes * | 301 (88.5%) |

| Correction of maligned teeth that require orthodontic treatment? n (%) | |

| No * | 98 (28.8%) |

| Yes | 242 (71.2%) |

| What are the considered disadvantages of dental veneers? n (%) | |

| Require removal of the tooth structure, n (%) | |

| No | 137 (40.3%) |

| Yes * | 203 (59.7%) |

| May present an unpleasant odor (over contoured)? n (%) | |

| No | 121 (35.6%) |

| Yes * | 219 (64.4%) |

| May negatively affect the gums (over-contoured)? n (%) | |

| No | 110 (32.4%) |

| Yes * | 230 (67.6%) |

| May fracture due to a specific way of eating? n (%) | |

| No | 68 (20.0%) |

| Yes * | 272 (80.0%) |

| Require extensive care and hygiene? n (%) | |

| No | 51 (15.0%) |

| Yes * | 289 (85.0%) |

| If you decide to remove your veneers, can we have the original teeth as they were before? n (%) | |

| I don’t know. | 170 (50.0%) |

| No * | 136 (40.0%) |

| Yes | 34 (10.0%) |

| Do you know how many visits are required before the cementation? n (%) | |

| I don’t know | 194 (57.1%) |

| One visit | 26 (7.6%) |

| Several visits * | 120 (35.3%) |

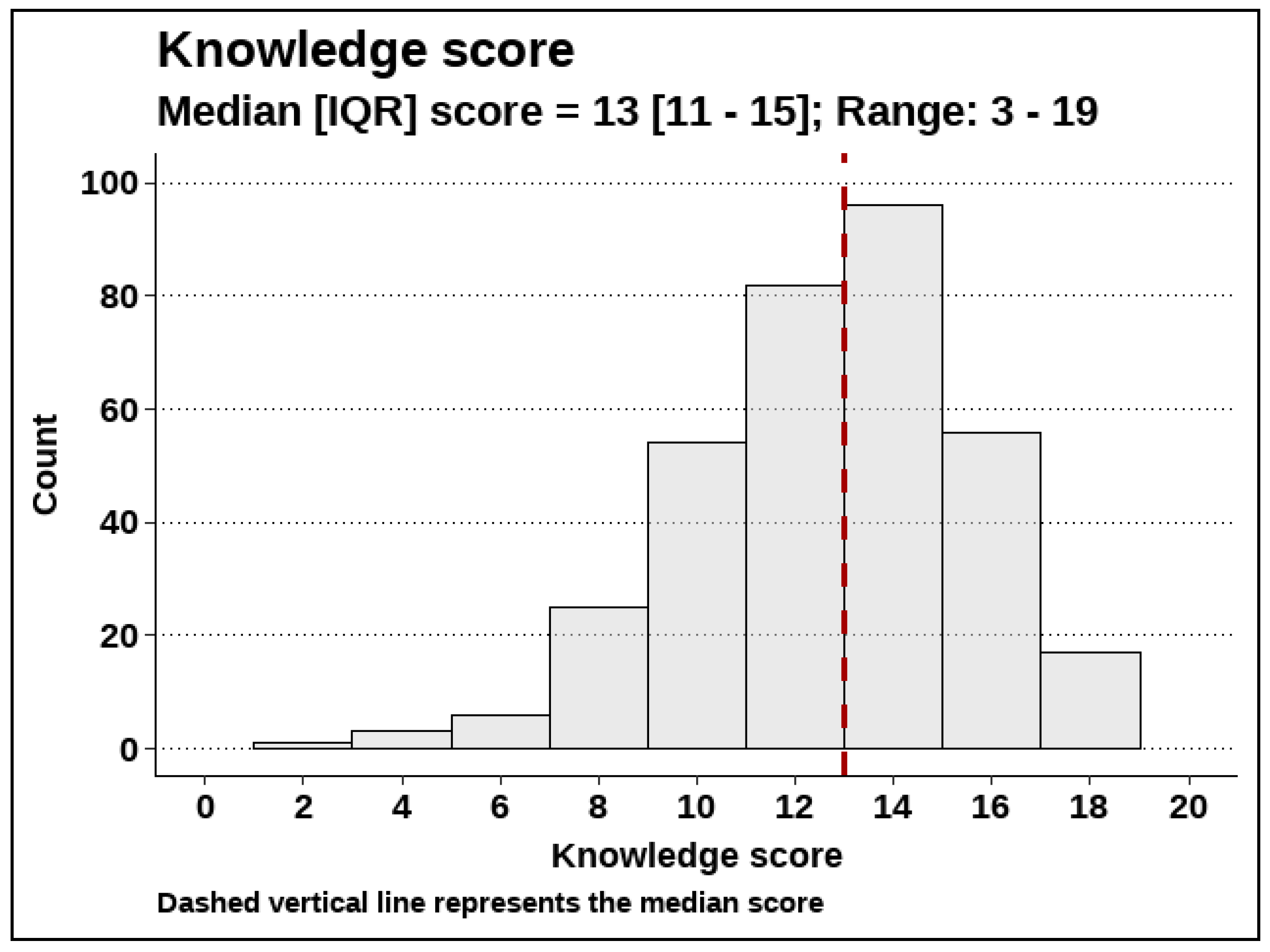

| Variables | Median Score | IQR of Score | p-Value c | Effect Size d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 18–24 | 13.50 | 11.00–15.75 | 0.354 a | 0.001 |

| 25–34 | 13.50 | 10.00–15.25 | |||

| 35–44 | 13.00 | 12.00–15.00 | |||

| 45–54 | 14.00 | 12.00–15.00 | |||

| 55 and more | 13.00 | 10.00–13.00 | |||

| Gender | Female | 14.00 | 12.00–15.00 | <0.001 * b | 0.281 |

| Male | 11.00 | 9.00–14.00 | |||

| Nationality | Non-Saudi | 11.00 | 10.00–11.50 | 0.005 * b | 0.152 |

| Saudi | 14.00 | 12.00–15.00 | |||

| Which region do you live in? | Central Region | 13.00 | 11.00–16.00 | 0.630 a | −0.004 |

| Eastern Region | 13.00 | 11.25–15.00 | |||

| Northern Region | 13.50 | 11.75–15.25 | |||

| Southern Region | 14.00 | 12.25–15.00 | |||

| Western Region | 13.00 | 11.00–15.00 | |||

| Marital status | Married | 13.00 | 11.00–15.00 | 0.520 b | 0.035 |

| Single | 14.00 | 11.00–15.00 | |||

| Educational level | High school or less | 13.00 | 10.00–15.00 | 0.014 * b | 0.134 |

| University degree | 14.00 | 12.00–15.00 | |||

| Did you have veneers? | No | 13.00 | 11.00–15.00 | 0.168 b | 0.075 |

| Yes | 14.00 | 12.00–16.00 | |||

| Do you work in the dental field? | No | 13.00 | 11.00–15.00 | 0.036 * b | 0.114 |

| Yes | 16.00 | 12.50–18.00 |

| Characteristic | Adjusted B (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | ||

| 18–24 | — | |

| 25–34 | −0.607 (−1.650 to 0.435) | 0.253 |

| 35–44 | 0.087 (−0.720 to 0.893) | 0.833 |

| 45–54 | 0.038 (−0.821 to 0.897) | 0.931 |

| 55 and more | −0.951 (−2.896 to 0.993) | 0.337 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | — | |

| Male | −2.184 (−3.079 to −1.289) | <0.001 * |

| Nationality | ||

| Non-Saudi | — | |

| Saudi | 1.988 (0.549 to 3.427) | 0.007 * |

| Educational level | ||

| Medium and less | — | |

| High school | 0.462 (−1.799 to 2.723) | 0.688 |

| Graduate | 1.724 (−0.830 to 4.278) | 0.185 |

| Academic | 1.049 (−1.102 to 3.200) | 0.338 |

| Do you work in the dental field? | ||

| No | — | |

| Yes | 1.068 (−0.864 to 3.000) | 0.278 |

| Did you have veneers? | ||

| No | — | |

| Yes | 0.279 (−0.684 to 1.242) | 0.569 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almutairi, D.; Alshahrani, S.; Balawi, A.; Alnasser, S.; Alshamlan, A.; Almugim, H.; Albalawi, A.; Baig, W.; Alzahrani, M.; Alaohali, A.; et al. Level of Awareness About Dental Veneers and Their Oral Hygiene Care Among the General Saudi Public: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172170

Almutairi D, Alshahrani S, Balawi A, Alnasser S, Alshamlan A, Almugim H, Albalawi A, Baig W, Alzahrani M, Alaohali A, et al. Level of Awareness About Dental Veneers and Their Oral Hygiene Care Among the General Saudi Public: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172170

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmutairi, Diaa, Saeed Alshahrani, Amwaj Balawi, Shahad Alnasser, Abeer Alshamlan, Hutham Almugim, Awatif Albalawi, Waheed Baig, Mohammad Alzahrani, Abeer Alaohali, and et al. 2025. "Level of Awareness About Dental Veneers and Their Oral Hygiene Care Among the General Saudi Public: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172170

APA StyleAlmutairi, D., Alshahrani, S., Balawi, A., Alnasser, S., Alshamlan, A., Almugim, H., Albalawi, A., Baig, W., Alzahrani, M., Alaohali, A., Alqasim, A., & Alharbi, M. A. (2025). Level of Awareness About Dental Veneers and Their Oral Hygiene Care Among the General Saudi Public: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(17), 2170. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172170