Quality of Life of Children with Cerebral Palsy and Its Association with Their Physical Activity Levels: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. The Survey Instrument

2.2.1. Cerebral Palsy Classification System

2.2.2. Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life Questionnaire-Child

2.2.3. Parent-Reported Physical Activity

- Physical activities levels: Over the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 min per day? With physical activity we mean any activity that increases your heart rate and makes you get out of breath some of the time. Response options: 0 days, 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, 4 days, 5 days, 6 days to 7 days.

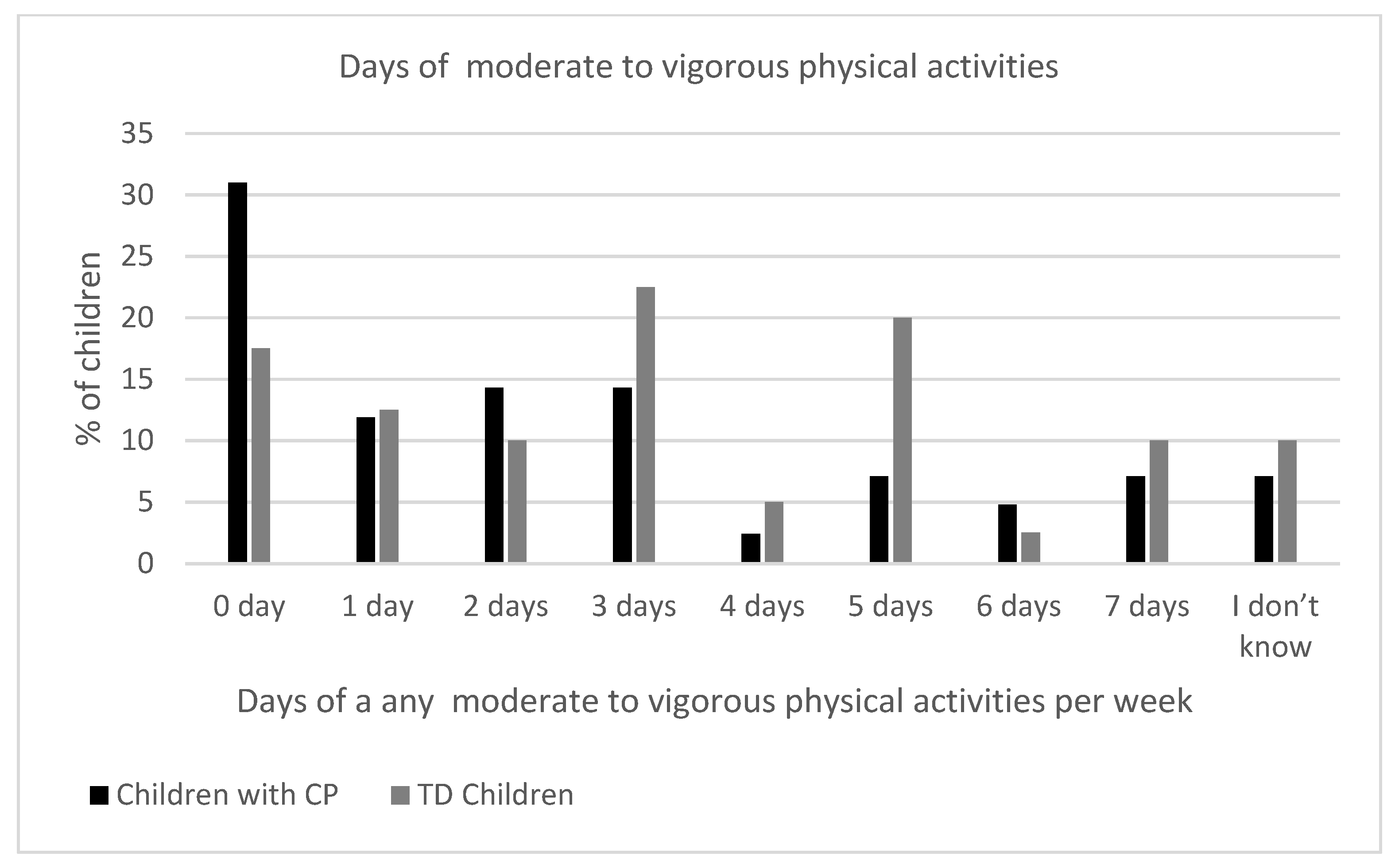

- Days of moderate to vigorous physical activities: How many days did your child practice physical activities to strengthen his/her bones and muscles (e.g., rope jumping, climbing an elevated object, running)? Response options: 0 days, 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, 4 days, 5 days, 6 days, 7 days, or I do not know.

- Duration of moderate to vigorous physical activities: In the days when your child practiced physical activities to strengthen his/her bones and muscles (e.g., rope jumping, climbing an elevated object, running), how much time does your child approximately spend per day doing this activity? Response options: None, approximately less than 30 min, approximately more than 30 min, approximately 60 min or more, or I do not know.

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Days of Physical Activity of Children with Cerebral Palsy and Typically Developing Children

3.3. Quality of Life

3.4. The Association Between Physical Activity and Quality of Life in Children with Cerebral Palsy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CP | Cerebral Palsy |

| CP-QoL | Quality of Life Questionnaire for Parents of Children with Cerebral Palsy |

| CP-QoL-Child | Quality of Life Questionnaire for Children Aged 4–12 Years with Cerebral Palsy |

| GMFCS (E&R) | Gross Motor Function Classification System (Expanded & Revised) |

References

- Bax, M.; Goldstein, M.; Rosenbaum, P.; Leviton, A.; Paneth, N.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B.; Damiano, D. Proposed definition and classification of cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2005, 47, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskoui, M.; Coutinho, F.; Dykeman, J.; Jetté, N.; Pringsheim, T. An update on the prevalence of cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2013, 55, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornson, K.F.; Belza, B.; Kartin, D.; Logsdon, R.; McLaughlin, J.F. Ambulatory physical activity performance in youth with cerebral palsy and youth who are developing typically. Phys. Ther. 2007, 87, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majnemer, A.; Shevell, M.; Law, M.; Birnbaum, R.; Chilingaryan, G.; Rosenbaum, P.; Poulin, C. Participation and enjoyment of leisure activities in school-aged children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2008, 50, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palisano, R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Walter, S.; Russell, D.; Wood, E.; Galuppi, B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1997, 39, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaud, C.; White-Koning, M.; Michelsen, S.I.; Parkes, J.; Parkinson, K.; Thyen, U.; Beckung, E.; Dickinson, H.O.; Fauconnier, J.; Marcelli, M.; et al. Parent-reported quality of life of children with cerebral palsy in Europe. Pediatrics 2008, 121, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, T.; Dorstyn, D.; Crettenden, A. Quality of life in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vila-Nova, F.; Santos, S.; Oliveira, R.; Cordovil, R. Parent-report health-related quality of life in school-aged children with cerebral palsy: A cross-sectional study. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2022, 3, 1080146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, C.A.; Toohey, M.; Ferguson, M. Physical activity predicts quality of life and happiness in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 38, 865–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly, A.; Davis, E.; Waters, E.; Mackinnon, A.; Reddihough, D.; Boyd, R.; Reid, S.; Graham, H.K. The relationship between quality of life and functioning for children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2008, 50, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colver, A.; Rapp, M.; Eisemann, N.; Ehlinger, V.; Thyen, U.; Dickinson, H.O.; Parkes, J.; Parkinson, K.; Nystrand, M.; Fauconnier, J.; et al. Self-reported quality of life of adolescents with cerebral palsy: A cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Lancet 2015, 385, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Tedla, J.S.; Sangadala, D.R.; Asiri, F. Quality of life among children with cerebral palsy in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and various factors influencing it: A cross-sectional study. J. Disabil. Res. 2024, 3, 20240050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, A.; Hassan, M.S.; Park, J.H.; Hassan, S.U.N.; Parveen, N. The Role of Environmental Quality of Life in the Physical Activity Status of Individuals with and without Physical Disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asiri, F.; Tedla, J.S.; Sangadala, D.R.; Reddy, R.S.; Alshahrani, M.S.; Gular, K.; Dixit, S.; Kakaraparthi, V.; Nayak, A.; Aldarami, M.; et al. Quality of life among caregivers of children with disabilities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. J. Disabil. Res. 2023, 2, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.-Y. Stability of the gross motor function classification system in children with cerebral palsy for two years. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, P. What Is Gross Motor Function Classification System. Available online: https://cpresource.org/topic/what-cerebral-palsy/what-gross-motor-function-classification-system (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Almasri, N.; Saleh, M. Inter-rater agreement of the Arabic Gross Motor Classification System Expanded & Revised in children with cerebral palsy in Jordan. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 37, 1895–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GMFCS Family & Self Report Questionnaire in Arabic. Available online: https://canchild.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/GMFCS_Family_Questionnaire_Arabic_FINAL.pdf?license=yes (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Waters, E.; Davis, E.; Mackinnon, A.; Boyd, R.; Graham, H.K.; Kai Lo, S.; Wolfe, R.; Stevenson, R.; Bjornson, K.; Blair, E.; et al. Psychometric properties of the quality of life questionnaire for children with CP. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.; Davis, E.; Boyd, R.; Reddihough, D.; Mackinnon, A.; Graham, H.K.; Lo, S.K.; Wolfe, R.; Stevenson, R.; Bjornson, K.; et al. Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life Questionnaire for Children (CP QOL-Child) Manual; University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2013; Available online: https://www.ausacpdm.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/CPQOL-Child-manual.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Prochaska, J.J.; Sallis, J.F.; Long, B. A physical activity screening measure for use with adolescents in primary care. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2001, 155, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, S.; Brazo-Sayavera, J.; González, S.A.; Janssen, I.; Manyanga, T.; Oyeyemi, A.L.; Picard, P.; Sherar, L.B.; Turner, E.; Tremblay, M.S. Global prevalence of physical activity for children and adolescents; inconsistencies, research gaps, and recommendations: A narrative review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Webster, C.A.; Stodden, D.F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of physical activity interventions to increase elementary children’s motor competence: A comprehensive school physical activity program perspective. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reedman, S.E.; Jayan, L.; Boyd, R.N.; Ziviani, J.; Elliott, C.; Sakzewski, L. Descriptive contents analysis of ParticiPAte CP: A participation-focused intervention to promote physical activity participation in children with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 44, 7167–7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa Junior, R.R.D.; Souto, D.O.; Camargos, A.C.R.; Clutterbuck, G.L.; Leite, H.R. Moving together is better: A systematic review with meta-analysis of sports-focused interventions aiming to improve physical activity participation in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 2398–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Suk, M.H.; Yoo, S.; Kwon, J.Y. Physical activity energy expenditure predicts quality of life in ambulatory school-age children with cerebral palsy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keawutan, P.; Bell, K.L.; Oftedal, S.; Davies, P.S.W.; Ware, R.S.; Boyd, R.N. Quality of life and habitual physical activity in children with cerebral palsy aged 5 years: A cross-sectional study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 74, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, M.; García-Galant, M.; Laporta-Hoyos, O.; Ballester-Plane, J.; Jorba-Bertran, A.; Caldu, X.; Miralbel, J.; Alonso, X.; Meléndez-Plumed, M.; Toro-Tamargo, E.; et al. Factors related to quality of life in children with cerebral palsy. Pediatr. Neurol. 2023, 141, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milićević, M. Functional and environmental predictors of health-related quality of life of school-age children with cerebral palsy: A cross-sectional study of caregiver perspectives. Child Care Health Dev. 2023, 49, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostojic, K.; Karem, I.; Paget, S.P.; Berg, A.; Dee-Price, B.J.; Lingam, R.; Dale, R.C.; Eapen, V.; Woolfenden, S.; EPIC-CP Group. Social determinants of health for children with cerebral palsy and their families. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2024, 66, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reedman, S.; Boyd, R.N.; Sakzewski, L. The efficacy of interventions to increase physical activity participation of children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Children with CP (n = 42) | TD Children (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 8.29 ± 1.79 | 8.35 ± 1.76 |

| Sex | ||

| Male, n (%) | 28 (66.7%) | 14 (35%) |

| Female, n (%) | 14 (33.3%) | 26 (65.5%) |

| Residence | ||

| Riyadh, n (%) | 12 (28.6%) | 33 (82.5%) |

| Outside Riyadh, n (%) | 30 (71.4%) | 7 (17.5%) |

| Attending school | 31 (74%) | 40 (100%) |

| Caregiver education | ||

| High school or less, n (%) | 10 (23.8%) | 12 (30%) |

| Diploma, n (%) | 6 (14.3%) | 4 (10%) |

| Bachelor, n (%) | 24 (57.1%) | 19 (47.5%) |

| Postgraduate studies, n (%) | 2 (4.8%) | 5 (12.5%) |

| GMFCS level | ||

| Level I, n (%) | 2 (4.8%) | - |

| Level II, n (%) | 8 (19%) | - |

| Level III, n (%) | 9 (21.4%) | - |

| Level IV, n (%) | 9 (21.4%) | - |

| Level V, n (%) | 14 (33.3%) | - |

| Quality of Life Domain | n | Min | Maxi | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social well-being and acceptance | 42 | 5.68 | 100.00 | 71.5097 | 26.29243 |

| Feelings about functioning | 42 | 8.33 | 96.88 | 56.6716 | 25.87401 |

| Participation and physical health | 42 | 2.27 | 100.00 | 61.0119 | 26.31170 |

| Emotional well-being and self-esteem | 42 | 0.00 | 87.50 | 66.8155 | 19.59421 |

| Access to services | 42 | 0.00 | 77.88 | 37.7060 | 18.26434 |

| Pain and effect(s) of disability | 42 | 0.00 | 75.00 | 41.7426 | 19.48737 |

| Family health | 42 | 15.00 | 100.00 | 63.5714 | 25.54971 |

| Quality of Life Domain | Ambulation Status (GMFCS Level) | n | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General QoL | Ambulant (I–III) | 19 | 55.39 | 16.14 | 3.70 |

| Non-Ambulant (IV–V) | 23 | 52.46 | 18.21 | 3.79 | |

| Social well-being and acceptance | Ambulant (I–III) | 19 | 71.11 | 24.44 | 5.60 |

| Non-Ambulant (IV–V) | 23 | 71.84 | 28.27 | 5.89 | |

| Feelings about functioning | Ambulant (I–III) | 19 | 65.57 | 24.25 | 5.56 |

| Non-Ambulant (IV–V) | 23 | 49.32 | 25.33 | 5.28 | |

| Participation and physical health | Ambulant (I–III) | 19 | 64.35 | 22.14 | 5.08 |

| Non-Ambulant (IV–V) | 23 | 58.25 | 29.52 | 6.15 | |

| Emotional well-being and self-esteem | Ambulant (I–III) | 19 | 66.34 | 21.09 | 4.84 |

| Non-Ambulant (IV–V) | 23 | 67.21 | 18.74 | 3.91 | |

| Access to services | Ambulant (I–III) | 19 | 35.83 | 15.89 | 3.64 |

| Non-Ambulant (IV–V) | 23 | 39.25 | 20.24 | 4.22 | |

| Pain and effect(s) of disability | Ambulant (I–III) | 19 | 41.81 | 19.65 | 4.51 |

| Non-Ambulant (IV–V) | 23 | 41.69 | 19.79 | 4.13 | |

| Family health | Ambulant (I–III) | 19 | 63.68 | 24.30 | 5.57 |

| Non-Ambulant (IV–V) | 23 | 63.47 | 27.08 | 5.65 |

| Regression Coefficients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| General QoL | (Constant) | 43.393 | 4.116 | 10.542 | 0.000 | |

| PA | 4.941 | 1.588 | 0.441 | 3.111 | 0.003 * | |

| Social well-being and acceptance | (Constant) | 56.260 | 6.370 | 8.832 | 0.000 | |

| PA | 7.251 | 2.458 | 0.423 | 2.950 | 0.005 * | |

| Feelings about functioning | (Constant) | 39.124 | 6.013 | 6.506 | 0.000 | |

| PA | 8.343 | 2.320 | 0.494 | 3.596 | 0.001 * | |

| Participation and physical health | (Constant) | 45.613 | 6.362 | 7.169 | 0.000 | |

| PA | 7.322 | 2.455 | 0.427 | 2.983 | 0.005 * | |

| Emotional well-being and Self-esteem | (Constant) | 57.020 | 4.878 | 11.689 | 0.000 | |

| PA | 4.658 | 1.882 | 0.364 | 2.474 | 0.018 * | |

| Access to services | (Constant) | 34.989 | 4.854 | 7.208 | 0.000 | |

| PA | 1.292 | 1.873 | 0.108 | 0.690 | 0.494 | |

| Pain and effect(s) of disability | (Constant) | 35.404 | 5.061 | 6.995 | 0.000 | |

| PA | 3.014 | 1.953 | 0.237 | 1.543 | 0.131 | |

| Family health | (Constant) | 58.451 | 6.757 | 8.650 | 0.000 | |

| PA | 2.435 | 2.607 | 0.146 | 0.934 | 0.356 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albesher, R.A.; Basoudan, R.M.; Ghufayri, A.; Aldayel, D.; Fagihi, D.; Alzeer, S.; Althurwi, S.; Aljarallah, N.; Aljuhani, T.; Alghadier, M. Quality of Life of Children with Cerebral Palsy and Its Association with Their Physical Activity Levels: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2166. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172166

Albesher RA, Basoudan RM, Ghufayri A, Aldayel D, Fagihi D, Alzeer S, Althurwi S, Aljarallah N, Aljuhani T, Alghadier M. Quality of Life of Children with Cerebral Palsy and Its Association with Their Physical Activity Levels: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2166. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172166

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbesher, Reem A., Reem M. Basoudan, Areej Ghufayri, Dana Aldayel, Dareen Fagihi, Shahad Alzeer, Shaima Althurwi, Nouf Aljarallah, Turki Aljuhani, and Mshari Alghadier. 2025. "Quality of Life of Children with Cerebral Palsy and Its Association with Their Physical Activity Levels: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2166. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172166

APA StyleAlbesher, R. A., Basoudan, R. M., Ghufayri, A., Aldayel, D., Fagihi, D., Alzeer, S., Althurwi, S., Aljarallah, N., Aljuhani, T., & Alghadier, M. (2025). Quality of Life of Children with Cerebral Palsy and Its Association with Their Physical Activity Levels: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(17), 2166. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172166