Guilt in the Context of Work-Family Conflict, Partner Support, and Life Satisfaction Among Health Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Predictors: family-to-work conflict, work-to-family conflict, guilt proneness.

- Criteria: family-work guilt, work-family guilt, job satisfaction, life satisfaction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Study Instruments

- Work-family conflict was evaluated utilizing the Work-Family Conflict Scale [49], which comprises 18 items, two directional categories (work-family and family-work), and three dimensions for each direction (time, tension, and behavior). The items assess both work-to-family conflict (e.g., the following: the time dimension: “Work keeps me from family activities more than I would like”; the tension dimension: “When I return from work, I am often too exhausted to participate in family activities/responsibilities”; and the behavior dimension: “Behaviors that make me effective at work do not help me be a better parent and spouse”) and family-to-work conflict (e.g., the following: the time dimension: “The time I devote to family responsibilities often interferes with my work responsibilities”; the tension dimension: “Due to stress at home, I am often preoccupied with family problems at work”; and the behavior dimension: “Behaviors that are beneficial to me at home do not seem to be effective at work”). Responses were recorded on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 6 (“strongly agree”). To ascertain the extent of work-to-family and family-to-work conflicts, total scores were computed for each dimension (work interference with family and family interference with work). A higher score signifies a greater level of work-family or family-work conflict. The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient for the work-family interface factor is 0.84, and for the family-work interface factor, it is 0.85.

- Guilt proneness: Guilt proneness was assessed using the Five-Item Guilt Proneness Scale (GP-5), as developed by Cohen et al. in 2015 [50]. This scale comprises five items, with responses measured on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“very unlikely”) to 5 (“very likely”). An average score is computed across the five items to quantify the respondent’s level of guilt proneness, with higher scores indicating a greater tendency towards guilt. The internal consistency of the scale, as measured using Cronbach’s alpha, was found to be 0.67.

- Work-family guilt and family-work guilt: The Work-Family Guilt Scale (WFGS), developed by McElwain, Korabik, and Chappell (2005) [51], was employed to measure both work-family guilt and family-work guilt. Responses to this scale were recorded on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 6 (“strongly agree”). The scale is calculated on a dimensional basis; higher scores reflect greater levels of guilt associated with work-to-family and family-to-work conflict. The internal consistency coefficients, as determined using Cronbach’s alpha, were 0.86 for family-to-work conflict guilt and 0.85 for work-to-family conflict guilt.

- Job satisfaction: Job satisfaction was measured using the Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS), which was developed by Spector (1985) [52]. This instrument consists of 36 items distributed across nine subscales, each containing four items. Responses are rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 6 (“strongly agree”), with 19 reverse-scored items. The total score, derived from the sum of individual items, serves as an indicator of overall job satisfaction. The internal consistency coefficient, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.91.

- Life satisfaction: Life satisfaction was measured using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), developed by Diener et al. (1985) [53]. This scale comprises five items, with responses rated on a Likert-type scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). A total score is computed to determine an individual’s level of life satisfaction, with the following interpretations: 31–35 indicates extreme satisfaction; 26–30 represents satisfaction; 21–25 indicates moderate satisfaction; 20 denotes neutrality; 15–19 represents mild dissatisfaction; 10–14 reflects dissatisfaction; and 5–9 indicates extreme dissatisfaction. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency was 0.87.

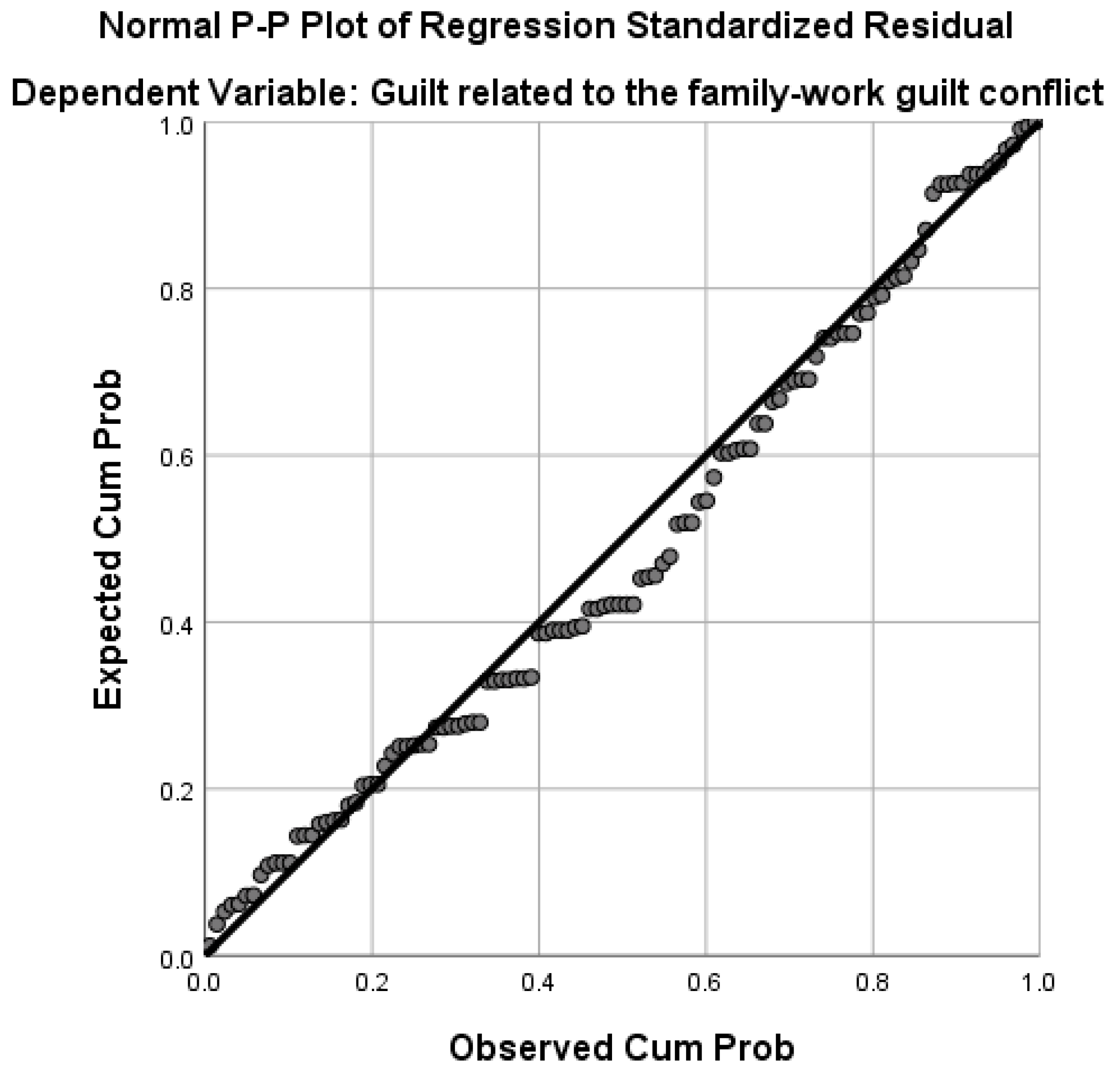

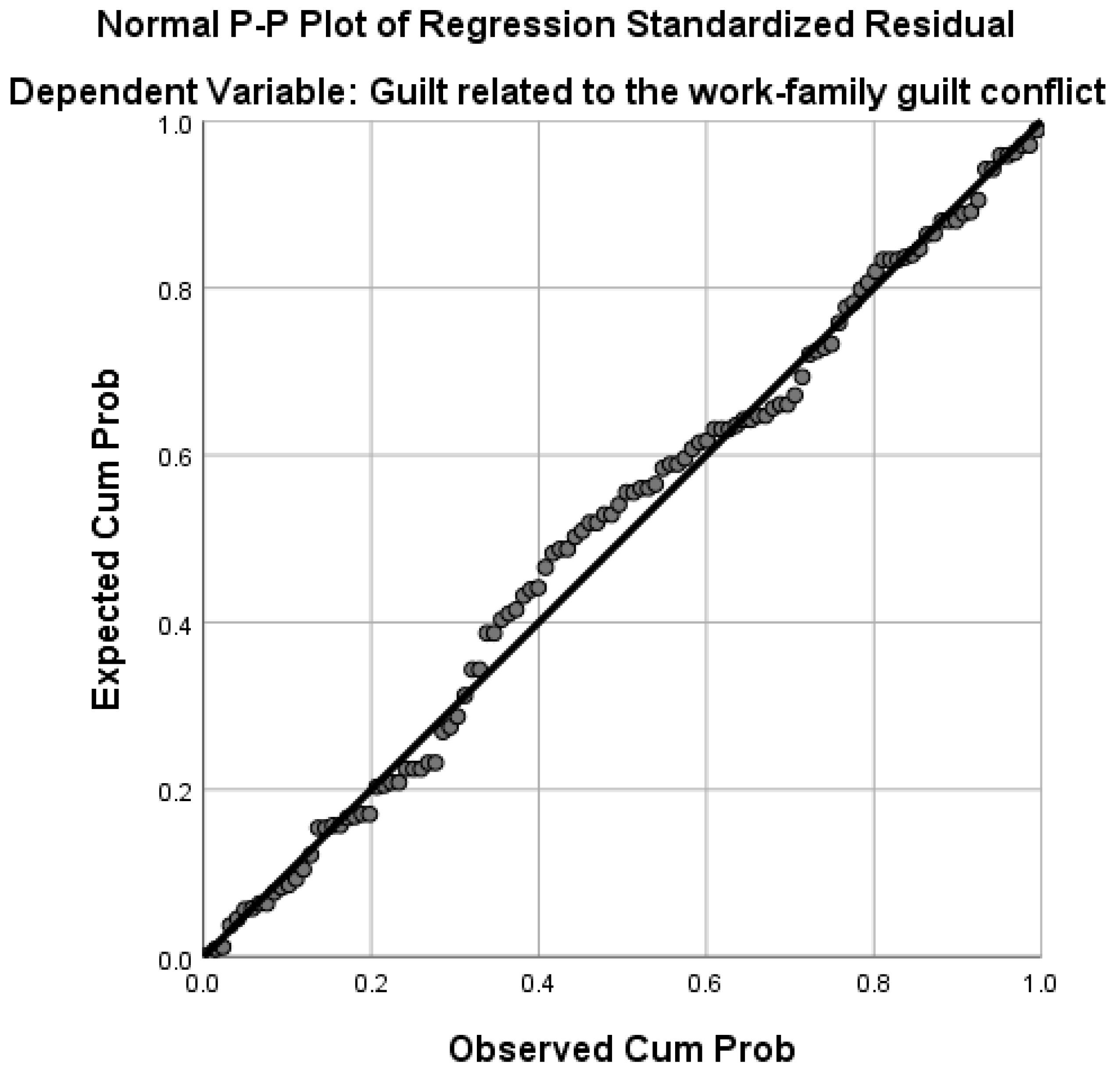

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Job-Related Data

3.2. Descriptive Statistics—Psychological Instruments

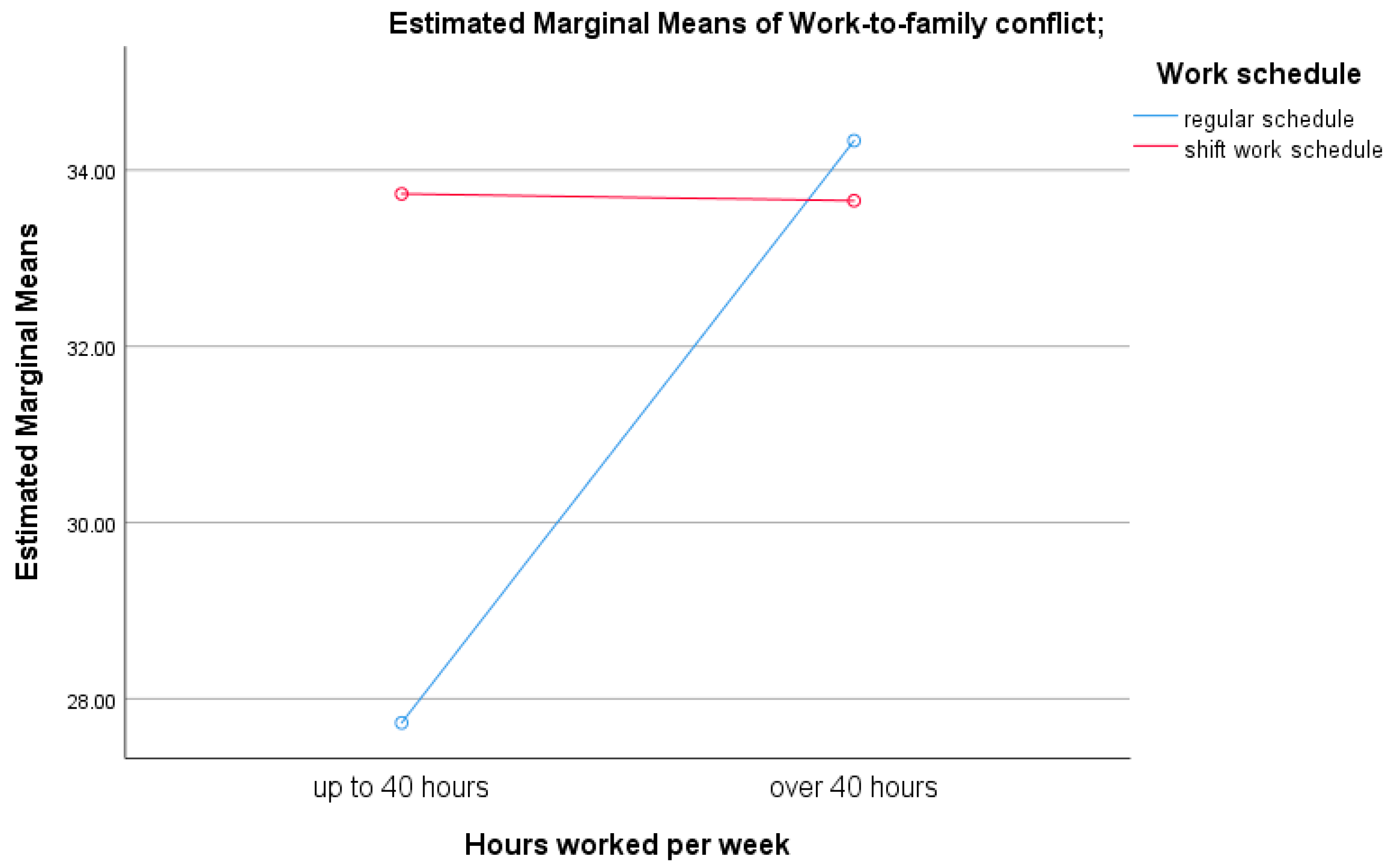

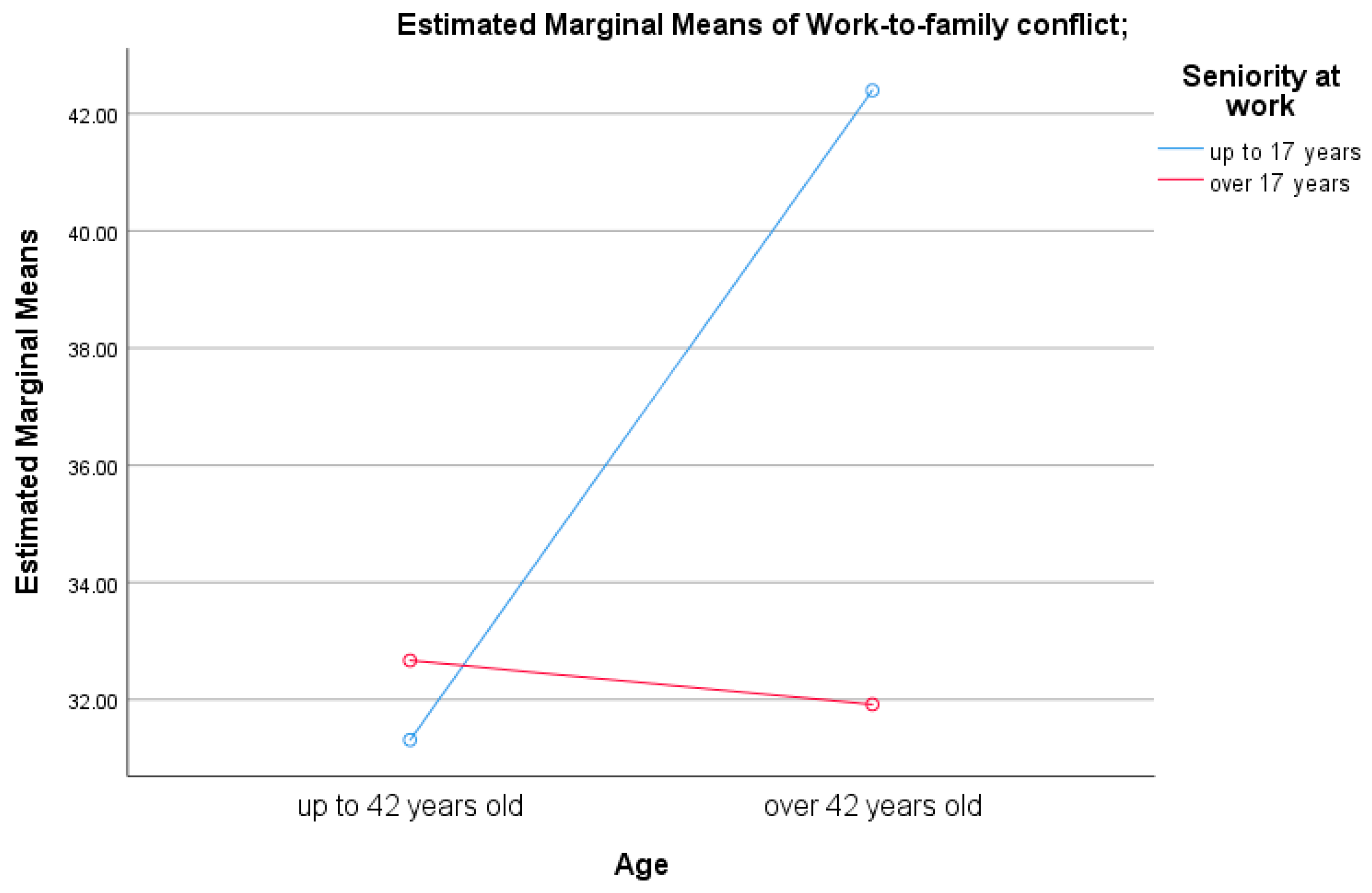

3.3. Inferential Data Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hammer, L.B.; Kossek, E.E.; Anger, W.K.; Bodner, T.; Zimmerman, K.L. Clarifying work-family intervention processes: The roles of work-family conflict and family-supportive supervisor behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annink, A.; Den Dulk, L.; Steijn, B. Work-family conflict among employees and the self-employed across Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 126, 571–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Schwind, K.M.; Wagner, D.T.; Johnson, M.D.; DeRue, D.S.; Ilgen, D.R. When can employees have a family life? The effects of daily workload and affect on work-family conflict and social behaviors at home. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Encarnação, T.; Viseu, J.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Conflict (work-family and family-work) and task performance: The role of well-being in this relationship. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borelli, J.L.; Nelson-Coffey, S.K.; River, L.M.; Birken, S.A.; Moss-Racusin, C. Bringing work home: Gender and parenting correlates of work-family guilt among parents of toddlers. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 1734–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borelli, J.L.; Nelson, S.K.; River, L.M.; Birken, S.A.; Moss-Racusin, C. Gender differences in work-family guilt in parents of young children. Sex Roles 2017, 6, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aybas, M.; Özçelik, G.; Uyargil, C. Can decent work explain employee-level outcomes? The roles of work-family and family-work conflict. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Ilies, R.; Scott, B.A. Work-family conflict and emotions: Effects at work and at home. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 59, 779–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, A.L.; Nogueira, F.; Gonçalves, S.P.; Marques, I.C. Work-family interface in the context of social responsibility: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources and conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, G.; Grima, D.; Romano, F.; Polimeni, A. Perceived work ability and work-family conflict in healthcare workers: An observational study in a teaching hospital in Italy. J. Occup. Health 2021, 63, e12271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pien, L.C.; Cheng, W.J.; Chou, K.R.; Lin, L.C. Effect of work-family conflict, psychological job demand, and job control on the health status of nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A. Job, family and individual factors as predictors of work-family conflict. J. Hum. Resour. Adult Learn. 2008, 4, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Perreault, M.; Power, N. Work-life balance as a personal responsibility: The impact on strategies for coping with interrole conflict. J. Occup. Sci. 2023, 30, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, C.; Viseu, J.; Pimenta, A.C.; Vinagre, H.; Ferreira, J.; Matavelli, R.; José, H.; Sousa, L.; Romana, F.A.; Valentim, O. The effect of coping on the relationship between work-family conflict and stress, anxiety, and depression. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.S.; Rotch, M.; Shifrin, N.; DeBaylo, P.; Lennox, A. Work-family conflict and enrichment predict work and family negative and positive affect and (sometimes) vice versa: A prospective analysis. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.; Pinto, E.; Santos, J.; Gonçalves, G. Effects of work-family and family-work conflict and guilt on job and life satisfaction. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 51, 305. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, C.; Gato, C.; Gonçalves, G.; Sousa, A. Work-family conflict and guilt: Effects on well-being and career satisfaction. In Occupational and Environmental Safety and Health IV; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Promislo, M.D.; Powell, G.N.; Allen, T.D. Examining the aftermath of work-family conflict episodes: Internal attributions, self-conscious emotions, family engagement, and well-being. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 127, 2139–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyar, S.L.; Mosley, D.C., Jr. The relationship between core self-evaluations and work and family satisfaction: The mediating role of work-family conflict and facilitation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 71, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Zhao, X.R. Employees’ work-family conflict moderating life and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhao, X.R.; Ma, E. A dual-path model of work-family conflict and hospitality employees’ job and life satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumu, J.R.; Tahmid, T.; Azad, M.A.K. Job satisfaction and intention to quit: A bibliometric review of work-family conflict and research agenda. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2020, 59, 151334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, B.; Yildiz, H.; Ayaz Arda, O. Relationship between work-family conflict and turnover intention in nurses: A meta-analytic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3317–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, E.; Zhao, Z.; Fang, Y.; Rotenstein, L.S.; Sen, S.; Guille, C. Experiences of work-family conflict and mental health symptoms by gender among physician parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2134315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntsche, S.; Kuntsche, E. Drinking to cope mediates the link between work-family conflict and alcohol use among mothers but not fathers of preschool children. Addict. Behav. 2021, 112, 106665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, K.J.; Taylor, J.F. Alcohol and cigarette use affecting the relationship between work-life conflict and physical health. Community Work Fam. 2022, 25, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.K.; Wan, M.; Carlson, D.; Kacmar, K.M.; Thompson, M. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: A mega-meta path analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, A.; Viney, R.; Needleman, S.; Griffin, A.; Woolf, K. ‘You can’t be a person and a doctor’: The work-life balance of doctors in training—A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e013897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T.R.; Panter, A.T.; Turan, N. Guilt proneness and moral character. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlers, D.E.; Hart, W.; Lambert, J.T. Judging the guilt of the un-guilty: The roles of “false positive” guilt and empathy in moral character perception. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2024, 113, 104613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, P. Dimensions of the Burnout Measure: Relationships with shame-and guilt-proneness in neonatal intensive care unit nurses. Aust. Crit. Care 2022, 35, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Wang, R.J.; Cygrymus, E.R.; Moturu, B.P. Looking ahead, looking around, and looking to others: Identifying core proactive behaviors in the quest for career sustainability. J. Career Assess. 2024, 32, 539–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claxton, G.; Hosie, P.; Sharma, P. Toward an effective occupational health and safety culture: A multiple stakeholder perspective. J. Saf. Res. 2022, 82, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, B.A.; Pichler, S.; Kossek, E.E.; Thompson, R.J.; Bodner, T. An Alpha, Beta and Gamma approach to evaluating occupational health organizational interventions: Learning from the measurement of work-family conflict change. Occup. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 513–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, M. Guilt work and family. Int. J. Employ. Stud. 2024, 32, 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, B.A.; Judge, T.A. Emotional responses to work-family conflict: An examination of gender role orientation among working men and women. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; Volume 127, p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Burggraf, S.A.; Wagner, P.E. Shame-proneness, guilt-proneness, and psychological symptoms. In Self-Conscious Emotions: The Psychology of Shame, Guilt, Embarrassment, and Pride; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 343–367. [Google Scholar]

- Aarntzen, L.; Derks, B.; Van Steenbergen, E.; Van Der Lippe, T. When work-family guilt becomes a women’s issue: Internalized gender stereotypes predict high guilt in working mothers but low guilt in working fathers. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 62, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.T.; Casper, W.J.; Lockwood, A.; Bordeaux, C.; Brinley, A. Work and family research in IO/OB: Content analysis and review of the literature (1980–2002). J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 124–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergeneli, A.; Ilsev, A.; Karapınar, P. Work-family Conflict and Job Satisfaction Relationship: The Roles of Gender and Interpretive Habits. Gend. Work Organ. 2009, 17, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, C.; Garside, J. Safeguarding the retention of nurses: A systematic review on determinants of nurse’s intentions to stay. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 2842–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marufu, T.C.; Collins, A.; Vargas, L.; Gillespie, L.; Almghairbi, D. Factors influencing retention among hospital nurses: Systematic review. Br. J. Nurs. 2021, 30, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniscalco, L.; Enea, M.; De Vries, N.; Mazzucco, W.; Boone, A.; Lavreysen, O.; Baranski, K.; Miceli, S.; Savatteri, A.; Fruscione, S.; et al. Intention to leave, depersonalisation and job satisfaction in physicians and nurses: A cross-sectional study in Europe. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Kao, S.-F.; Chang, T.-T.; Wu, H.-P.; Cooper, C.L. Work/family demands, work flexibility, work/family conflict, and their consequences at work: A national probability sample in Taiwan. Int. Perspect. Psychol. Res. Pract. Consult. 2011, 1, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Fan, J. Family boundary characteristics, work-family conflict and life satisfaction: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Psychol. 2015, 50, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Williams, L.J. Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2000, 56, 249–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T.R.; Kim, Y.; Panter, A.T. The five-item guilt proneness scale (GP-5). Differences 2014, 92, 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain, A.; Korabik, K.; Chappell, D.B. The work-family guilt scale. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Psychological Association, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E. Job Satisfaction Survey; Department of Psychology, University of South Florida: Tampa, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.C.; Smith, K.; Johnston, D.W. Exploring the Michigan model: The relationship of personality, managerial support and organizational structure with health outcomes in entrants to the healthcare environment. Work Stress 2005, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.; Golsch, K. Consequences of work-to-family conflicts for parental self-efficacy—The impact of gender and cultural background in Germany. J. Fam. Issues 2023, 44, 2644–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.P.; Wang, Y.M. Women’s work-family conflict and its consequences in commuter marriages: The moderating role of spouses’ family commitment in a dyad analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 860717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Armstrong, J. Further examination of the link between work-family conflict and physical health: The role of health-related behaviors. Am. Behav. Sci. 2006, 49, 1204–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Lee, K.H. Work-family conflict and work-life conflict. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management; Aldag, R.J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Minnotte, K.L.; Minnotte, M.C.; Bonstrom, J. Work-family conflicts and marital satisfaction among US workers: Does stress amplification matter? J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2015, 36, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, N.; Boone, A.; Godderis, L.; Bouman, J.; Szemik, S.; Matranga, D.; De Winter, P. The race to retain healthcare workers: A systematic review on factors that impact retention of nurses and physicians in hospitals. J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2023, 60, 00469580231159318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, N.; Lavreysen, O.; Boone, A.; Bouman, J.; Szemik, S.; Baranski, K.; Godderis, L.; De Winter, P. Retaining healthcare workers: A systematic review of strategies for sustaining power in the workplace. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taşdelen-Karçkay, A.; Bakalım, O. The mediating effect of work-life balance on the relationship between work-family conflict and life satisfaction. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2017, 26, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, J.H.; Ellis, G.D.; Baldwin, B.M. Marital satisfaction: An examination of its relationship to spouse support and congruence of commitment among runners. Leis. Sci. 1999, 21, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglalang, D.D.; Sorensen, G.; Hopcia, K.; Hashimoto, D.M.; Katigbak, C.; Pandey, S.; Takeuchi, D.; Sabbath, E.L. Job and family demands and burnout among healthcare workers: The moderating role of workplace flexibility. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 14, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaney, R.B.; Rice, K.G.; Mobley, M.; Trippi, J.; Ashby, J.S. The revised almost perfect scale. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2001, 34, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunfowora, B.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Lee, C.S.; Babalola, M.T.; Ren, S. Do moral disengagers experience guilt following workplace misconduct? Consequences for emotional exhaustion and task performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2023, 44, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, A.; Yanagida, T.; Camodeca, M.; Strohmeier, D. Information processing of social exclusion: Links with bullying, moral disengagement and guilt. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 75, 101292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, N. Reassessing the dimensionality of the moral emotions. Br. J. Psychol. 2003, 94, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbard, N.P. Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family roles. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 655–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.J.; Alliger, G.M. Role stressors, mood spillover, and perceptions of work-family conflict in employed parents. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 837–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhate, B.; Hirudayaraj, M.; Dirani, K.; Barhate, R.; Abadi, M. Career disruptions of married women in India: An exploratory investigation. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2021, 24, 401–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, T.; Husna, C.A. Familial support as a determinant of women career development: A qualitative study. Asian J. Soc. Sci. Leg. Stud. 2020, 2, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J.; Greenglass, E.R. Work-family conflict, spouse support, and nursing staff well-being during organizational restructuring. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1999, 4, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnunen, U.; Geurts, S.; Mauno, S. Work-to-family conflict and its relationship with satisfaction and well-being: A one-year longitudinal study on gender differences. Work Stress 2004, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, U.; Mauno, S. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict among employed women and men in Finland. Hum. Relat. 1998, 51, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Lyu, X.; Pan, L.; Chen, A. The role conflict-burnout-depression link among Chinese female health care and social service providers: The moderating effect of marriage and motherhood. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, P.A.; McGarry, J.; Maqsood, A. Spousal role expectations and marital conflict: Perspectives of men and women. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP7082–NP7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demos, J. Shame and guilt in early New England. In The Emotions; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1996; pp. 74–88. [Google Scholar]

- Robakowska, M.; Tyrańska-Fobke, A.; Walkiewicz, M.; Tartas, M.; Ślęzak, D.; Tomczak, W.; Balwicki, Ł.; Zorena, K.; Jałtuszewska, S. PerfectionisM and Burnout in health care Professionals. Emerg. Med. Serv. 2021, 8, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, H. The mediating role of self-compassion and its components in the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and life satisfaction among Chinese medical students. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 14769–14781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babapour, A.R.; Gahassab-Mozaffari, N.; Fathnezhad-Kazemi, A. Nurses’ job stress and its impact on quality of life and caring behaviors: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajet, G.S.; Offong, R.E.; Ajayi, M.P.; Iruonagbe, T.C.; Amoo, E.O. Work-family conflict and burnout among female medical doctors in selected hospitals Abuja. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 640, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N (%)/M ± 1 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 19 (16.70) |

| Female | 95 (83.30) |

| Age | 41.80 ± 9.50 |

| Number of working hours per week | 41.48 ± 13.91 |

| Years of experience in the medical field | 16.84 ± 9.68 |

| Number of children | |

| 1 | 66 (57.90) |

| 2 | 37 (32.50) |

| 3 | 8 (7) |

| 4 | 3 (2.60) |

| The partner helps in raising and educating the children | |

| Always | 24 (21.10) |

| Frequently | 23 (20.20) |

| Sometimes | 23 (20.20) |

| Rarely | 31 (27.20) |

| Never | 13 (11.40) |

| Having a person to help raise children | 59 (51.80) |

| Scale | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Work-family interface | 32.08, (8.39) |

| 2 | Family-work interface | 23.85, (8.17) |

| 3 | General guilt proneness | 4.65, (0.48) |

| 4 | Guilt related to the work-to-family conflict | 17.42, (4.78) |

| 5 | Guilt related to the family-to-work conflict | 7.61, (3.78) |

| 6 | Job satisfaction | 155.95, (27.15) |

| 7 | Life satisfaction | 26.48, (5.69) |

| Scale | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Work-family interface | 0.507 ** | 0.007 | 0.556 ** | 0.149 | −0.185 * | −0.234 * |

| 2 | Family-work interface | −0.012 | 0.256 ** | 0.547 ** | −0.106 | −0.318 ** | |

| 3 | General guilt proneness | −0.012 | −0.006 | −0.080 | 0.027 | 0.230 * | |

| 4 | Guilt related to the work-to-family conflict | 0.256 ** | −0.006 | 0.176 | 0.877 | −0.255 ** | |

| 5 | Guilt related to the family-to-work conflict | 0.547 ** | −0.080 | 0.176 | −0.995 | −0.152 | |

| 6 | Job satisfaction | −0.106 | 0.027 | 0.877 | −0.095 | 0.352 ** | |

| 7 | Life satisfaction | −0.318 ** | 0.230 * | −0.255 ** | −0.152 | 0.352 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Apostol, M.-M.; Iorga, M.; Rotariu, M. Guilt in the Context of Work-Family Conflict, Partner Support, and Life Satisfaction Among Health Professionals. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172145

Apostol M-M, Iorga M, Rotariu M. Guilt in the Context of Work-Family Conflict, Partner Support, and Life Satisfaction Among Health Professionals. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172145

Chicago/Turabian StyleApostol, Maria-Manuela, Magdalena Iorga, and Mariana Rotariu. 2025. "Guilt in the Context of Work-Family Conflict, Partner Support, and Life Satisfaction Among Health Professionals" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172145

APA StyleApostol, M.-M., Iorga, M., & Rotariu, M. (2025). Guilt in the Context of Work-Family Conflict, Partner Support, and Life Satisfaction Among Health Professionals. Healthcare, 13(17), 2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172145